Thi Qar University College of Medicine Internal Medicine Department

BYDr. FAEZ KHALAF, SUBSPACIALITY GIT

MBChB, FIBMS-CABMS(MED)

MD-FACP(US),FIBMS(GIT&HEP)Vascular Liver Disease

Metabolically, the liver is highly active and has large oxygen requirements. This places it at risk of ischaemic injury in settings of impaired perfusion.The risk is mitigated, however, by the dual perfusion of the liver (via portal vein as well as hepatic artery), with the former representing a low-pressure perfusion system that offers protection against the potential effects of arterial hypotension.

The single outflow through the hepatic vein and the low-pressure perfusion system of the portal vein make the liver vulnerable to venous thrombotic ischaemic in the context of Budd–Chiari syndrome and portal vein thrombosis, respectively

Hepatic arterial disease

Liver ischemia

Liver ischaemic injury is relatively common during hypotensive or hypoxic events and is under-diagnosed.

The characteristic pattern is one of rising transaminase values in the days following such an event (e.g. prolonged seizures).

Liver synthetic dysfunction and encephalopathy are uncommon but can occur.

Liver failure is very rare.

Diagnosis typically rests on clinical suspicion and exclusion of other potential aetiologies.

Treatment is aimed at optimising liver perfusion and oxygen delivery. Outcome is dictated by the morbidity and mortality associated with the underlying disease, given that liver ischaemia frequently occurs in the

context of other organ ischaemia in high-risk patients

Liver arterial disease

Hepatic arterial disease is rare outside the setting of liver transplantation and is difficult to diagnose.It can cause significant liver damage.

Hepatic artery occlusion may result from inadvertent injury during biliary surgery

or may be caused by emboli, neoplasms, polyarteritis nodosa, blunt trauma or radiation.

It usually causes severe upper abdominal pain with or without signs of circulatory shock.

LFTs show raised transaminases (AST or ALT usually > 1000 U/L), as in other causes of acute liver damage.

Patients usually survive if the liver and portal blood supply are otherwise normal

Hepatic artery aneurysms are extrahepatic in three quarters of cases and intrahepatic in one-quarter.

Atheroma, vasculitis, bacterial endocarditis and surgical or biopsy trauma are the main causes.

They usually lead to bleeding into the biliary tree, peritoneum or intestine,

and are best diagnosed by angiography.

Treatment is radiological or surgical.

Any of the vasculitides can affect the hepatic artery but this rarely causes symptoms.

Hepatic artery thrombosis is a recognised complication of liver transplantation and typically occurs in the early post-transplant period.

Clinical features are often related to bile duct rather than liver ischaemia because

of the dominant role of the hepatic artery in extrahepatic bile duct perfusion.

Manifestations can include bile duct anastomotic failure with bile leak or the development of late bile duct strictures.

Diagnosis and initial intervention are radiological in the first instance, with ERCP and biliary stenting being the principal approaches to the treatment of bile duct injury.

Portal venous disease

Portal venous thrombosis as a primary event is rare, but can occur in any condition predisposing to thrombosis.It may also complicate intra-abdominal inflammatory or neoplastic disease, and is a recognised cause of portal hypertension.

Acute portal venous thrombosis causes abdominal pain and diarrhoea, and may rarely lead to bowel infarction, requiring surgery.

Treatment is otherwise based on anticoagulation, although there are no randomised data on efficacy.

An underlying thrombophilia needs to be excluded.

Subacute thrombosis can be asymptomatic but may subsequently lead to extrahepatic portal hypertension .

Ascites is unusual in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, unless the albumin is particularly low.

Portal vein thrombosis can arise as a secondary event in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension,

And is a recognised cause of decompensation in patients with previously stable cirrhosis.

In patients showing such decompensation, portal vein patency should be assessed by ultrasound with Doppler flow studies

Hepatopulmonary syndrome

This condition is characterised by resistant hypoxemia(PaO2 < 9.3 kPa or 70 mm Hg), intrapulmonary vascular dilatation in patients with cirrhosis, and portal hypertension.Clinical features include finger clubbing, cyanosis, spider naevi

and a characteristic reduction in arterial oxygen saturation on standing.

The hypoxia is due to intrapulmonary shunting through direct arteriovenous communications.

Nitric oxide (NO) overproduction may be important in pathogenesis.

The Hepatopulmonary syndrome can be treated by liver transplantation but, if

severe (PaO2 < 6.7 kPa or 50 mm Hg), is associated with an increased operative risk.

Portopulmonary hypertension

This unusual complication of portal hypertension is similar to ‘primary pulmonary hypertension’ .

It is defined as pulmonary hypertension with increased pulmonary vascular resistance and a normal pulmonary artery wedge pressure in a patient with portal hypertension.

The condition is caused by vasoconstriction and obliteration of the pulmonary arterial system, and leads to breathlessness and fatigue.

Hepatic venous disease

Budd–Chiari syndromeThis uncommon condition is caused by thrombosis of the larger hepatic veins and sometimes the inferior vena cava.

Many patients have haematological disorders such as myelofibrosis, primary proliferative polycythaemia, paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria, or antithrombin III, protein C or protein S deficiencies

Pregnancy and oral contraceptive use, obstruction due to tumours (particularly carcinomas of the liver, kidneys or adrenals), congenital venous webs and occasionally inferior vena caval stenosis are the other main causes.

The underlying cause cannot be found in about 50% of patients, although this percentage is falling as molecular diagnostic tools (such as the JAK2 mutation in myelofibrosis) increase our capacity to diagnose underlying haematological disorders.

Hepatic congestion affecting the centrilobular areas is followed by centrilobular fibrosis, and eventually cirrhosis supervenes in those who survive long enough

Clinical features

Acute venous occlusion causes rapid development of upper abdominal pain, marked ascites and occasionally acute liver failureMore gradual occlusion causes gross ascites and, often, upper abdominal discomfort. Hepatomegaly, frequently with tenderness over the liver, is almost always present.

Peripheral oedema occurs only when there is inferior vena cava obstruction.

Features of cirrhosis and portal hypertension develop in those who survive the acute event.

investigations

The LFTs vary considerably, depending on the presentation, and can show the features of acute hepatitisAscitic fluid analysis shows a protein concentration above 25 g/L (exudate) in the early stages; however, this often falls later in the disease.

Doppler ultrasound may reveal obliteration of the hepatic veins and reversed flow or associated thrombosis in the portal vein.

CT may show enlargement of the caudate lobe, as it often has a separate venous drainage system that is not involved in the disease.

CT and MRI may also demonstrate occlusion of the hepatic veins and inferior vena cava.

Liver biopsy demonstrates centrilobular congestion with fibrosis, depending on the duration of the illness.

Venography is only needed if CT and MRI are unable to demonstrate the hepatic venous anatomy clearly.

Management

Predisposing causes should be treated as far as possible; where recent thrombosis is suspected, thrombolysis with streptokinase, followed by heparin and oral anticoagulation, should be considered.

Ascites is initially treated medically but often with only limited success.

Short hepatic venous strictures can be treated with angioplasty.

In the case of more extensive hepatic vein occlusion, many patients can be managed successfully by insertion of a covered TIPSS, followed by anticoagulation.

Surgical shunts, such as portacaval shunts, are less commonly performed now that TIPSS is available.

Occasionally, a web can be resected or an inferior vena caval stenosis dilated.

Progressive liver failure is an indication for liver transplantation and life-long anticoagulation.

Prognosis without transplantation or shunting is poor, particularly following an acute presentation with liver failure.

A 3-year survival of 50% is reported in those who survive the initial event. The 1- and 10-year survival following liver transplantation is 85% and 69%

respectively, and this compares with a 5- and 10-year survival of 87% and 37% following surgical shunting.

Veno-occlusive disease

Veno-occlusive disease (VOD) is a rare condition characterized by widespread occlusion of the small central hepatic veins.Pyrrolizidine alkaloids in Senecio and Heliotropium plants used to make teas, as well as cytotoxic drugs and hepatic irradiation, are all recognised causes.

VOD may develop in 10–20% of patients following haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (usually within the first 20 days), and carries a 90% mortality in severe cases.

Pathogenesis involves obliteration and fibrosis of terminal hepatic venules due to deposition of red cells, haemosiderin-laden macrophages and coagulation factors.

In this setting, VOD is thought to relate to preconditioning therapy with irradiation and cytotoxic chemotherapy

The clinical features are similar to those of the Budd–Chiari syndrome .

Investigations show evidence of venous outflow obstructionhistologically but, in contrast to Budd–Chiari, the large hepatic veins appear patent radiologically.

Transjugular liver biopsy (with portal pressure measurements) may

make the diagnosis.

Traditionally, treatment has been supportive, but defibrotide shows promise (the drug binds to vascular endothelial cells, promoting fibrinolysis and suppressing coagulation

Cardiac disease

Hepatic damage, due primarily to congestion, may develop in all forms of right heart failure usually, the clinical features are predominantly cardiac.

Very rarely, long-standing cardiac failure and hepatic congestion give rise to cardiac cirrhosis.

Cardiac causes of acute and chronic liver disease are under-diagnosed.

Treatment is that of the underlying heart disease

Nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver

This is the most common cause of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension in developed countries;it is characterised by small hepatocyte nodules throughout the liver without fibrosis, which can result in sinusoidal compression.

It is believed to be due to damage to small hepatic arterioles and portal venules. It occurs in older people and is associated with many conditions, including connective tissue disease, haematological diseases and immunosuppressive drugs, such as azathioprine.

The condition is usually asymptomatic, but occasionally presents with portal hypertension or with an abdominal mass.

The diagnosis is made by liver biopsy, which, in contrast to cirrhosis, shows nodule formation in the absence of fibrous septa.

Liver function is good and the prognosis is very favourable.

Management is based on treatment of the portal hypertension

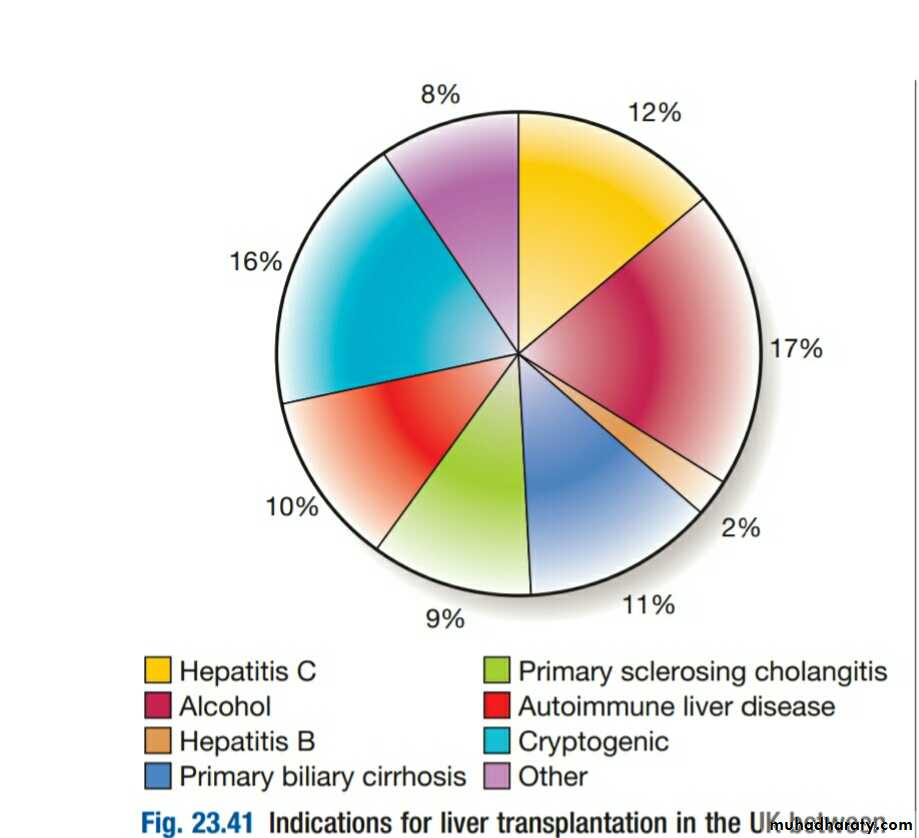

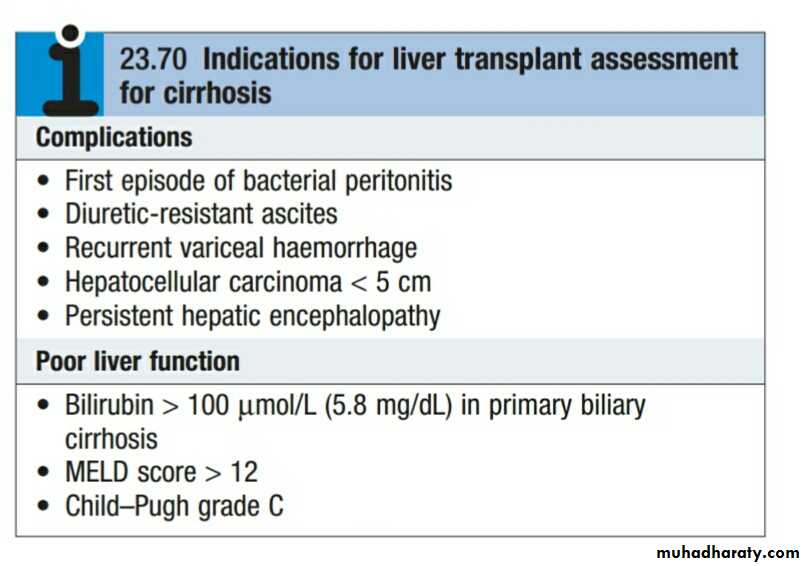

LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

Indications and contraindicationsThe main contraindications to transplantation are

sepsis,

extrahepatic malignancy,

active alcohol or other substance misuse,

and marked cardiorespiratory dysfunction.

Early complications

Primary graft non-functionTechnical complications

Rejection

Infections