1

THI QAR U. MEDICAL COLLEGE HEPATOLOGY LECTURES 2017

DEPARTMENT OF INTERNAL MEDICINE Dr. FAEZ KHALAF, SUBSPACIALITY GIT

Hepatitis C

This is caused by an RNA flavivirus.

Acute symptomatic infection with hepatitis C is rare

. Most individuals are

unaware of when they became infected and are

only identified when they develop chronic liver disease

.

Eighty per

cent of individuals exposed to the virus become chronically infected and late spontaneous viral clearance is rare

.

Hepatitis C is the cause of what used to be known as ‘non-A, non-B hepatitis’. Hepatitis C infection is usually

identified in asymptomatic individuals screened because they have risk factors for infection, such as previous

injecting drug use, or have incidentally been found to have abnormal liver blood tests. Although most individuals

remain asymptomatic

until progression to cirrhosis occurs,

fatigue can complicate chronic infection and is unrelated to the degree of liver damage

.

Risk factors for the acquisition of chronic hepatitis C infection

1.

Intravenous drug misuse (95% of new case s in the UK)

2.

Unscreened blood products

3.

Vertical transmission (3% risk)

4.

Needlestick injury (3% risk)

5.

Iatrogenic parenteral transmission (i.e. contaminated vaccination needles)

6.

Sharing toothbrushes/razors

Investigations:

a) Serology and virology:

The HCV protein contains several antigens that give rise

to antibodies in an infected person

and these are used in

diagnosis. It may take 6–12 weeks for antibodies to

appear in the blood following acute

infection such as

a needlestick injury.

In these cases, hepatitis C RNA can be identified in the blood as early as 2–4

weeks after infection

. Active infection is confirmed by the

presence of serum hepatitis C RNA in anyone who

is

antibody-positive.

Anti-HCV antibodies persist in serum even after viral clearance, whether spontaneous or post-

treatment.

b) Molecular analysis:

There are

six common viral genotypes

, the distribution

of which varies worldwide

. Genotype

has no effect on progression of liver disease but does affect response to treatment

. Genotype 1 is most common in

northern

Europe.

c) Liver function tests

: LFTs may be normal or show fluctuating serum transaminases

between 50 and 200 U/L.

Jaundice is rare and

only usually appears in end-stage cirrhosis.

d) Liver histology:

Serum transaminase levels in hepatitis C are a poor predictor of the degree of liver fibrosis

and so

a liver

biopsy is often required to stage the degree of liver

damage. The degree of inflammation and fibrosis can be

scored histologically. The most common scoring system

used in hepatitis C is the Metavir system, which scores

fibrosis from 1 to 4, the latter equating to cirrhosis.

Management:

*

The aim of treatment is to eradicate infection.

Until recently, the treatment of choice

new HCV DAAs have

been licensed in the last guide lines.

*

old( use as part of combination therapies for HCV infection was dual therapy with pegylated interferon-alfa

given as a weekly subcutaneous injection, together with oral ribavirin, a synthetic nucleotide analogue. The

main side-effects of ribavirin are haemolytic anaemia and teratogenicity. Side-effects of interferon are

significant and include flu-like symptoms, irritability and depression, all of which can affect quality of life.

Virological relapse can occur in the first 3 months after stopping treatment)

2

and cure is defined as loss of virus from serum 6 months after completing therapy (sustained virological response

, or

SVR). The length of treatment and efficacy depend on viral genotype (12 months’ treatment for genotype 1 results in

a 40% SVR, whereas 6 months’ treatment for genotype 2 or 3 leads to an SVR in > 70%).

Response to treatment is better in patients who have an early virological response, as defined by negativity of HCV

RNA in serum 1 month after starting therapy

, and it may be possible to shorten the duration of therapy in this

patient group. The recent availability of triple therapy with the addition of protease inhibitors such as telaprevir and

boceprevir to standard pegylated interferon/ribavirin has provided a significant advance in therapy, with SVR rates

for genotype 1 individuals comparable to those previously only achieved in genotypes 2 and 3.

Liver transplantation should be considered when complications of cirrhosis occur, such as diuretic resistant ascites.

Unfortunately, hepatitis C almost

always recurs in the transplanted liver and up to 15% of patients will develop

cirrhosis in the liver graft within 5 years of transplantation.

There is no active or passive protection against HCV

. Progression from chronic hepatitis to cirrhosis occurs over 20–

40 years. Risk factors for progression include1. Male gender, 2. Immunosuppression (such as co-infection with HIV),

3.prothrombotic states and4. Heavy alcohol misuse.

Not everyone with hepatitis C infection will necessarily develop cirrhosis but approximately 20% do so within 20

years.

Once cirrhosis has developed, the 5- and 10-year survival rates are 95% and 81% respectively.

One-quarter of people with cirrhosis will develop complications within 10 years and, once complications like ascites

have arisen, the 5-year survival is around 50%.

Once cirrhosis is present, 2–5% per year will develop primary hepatocellular carcinoma.

Liver abscess:

Liver abscesses are classified as pyogenic, hydatid or amoebic.

Pyogenic liver abscess

Pyogenic liver abscesses are uncommon but important because they are

potentially curable

, carry significant

morbidity and mortality if untreated, and are easily overlooked.

The mortality of liver abscesses is 20–40%;

failure to

make the diagnosis is the most common cause of death. Older patients and those with multiple abscesses also have

a higher mortality.

Pathophysiology

Infection can reach the liver in several ways (Box 23.50).

Pyogenic abscesses are most common in

older patients

and usually result from ascending infection due to

biliary obstruction (cholangitis) or contiguous

spread

from an empyema of the gallbladder. They can also complicate

dental sepsis. Abscesses complicating

suppurative

appendicitis used to be common in young adults but

are now rare. Immunocompromised patients are

particularly

likely to develop liver abscesses. Single lesions

are more common in the right liver; multiple abscesses

are usually due to infection secondary to biliary obstruction.

E. coli and various streptococci, particularly Strep.

milleri, are the most common organisms; anaerobes,

including streptococci and Bacteroides, can often be

found

when infection has been transmitted from large

bowel pathology via the portal vein, and multiple organisms

are

present in one-third of patients.

23.50 Causes of pyogenic liver abscesses

1.

Biliary obstruction (cholangitis)

2.

Haematogenous

Portal vein (mesenteric infections)

Hepatic artery (bacteraemia)

3.

Direct extension

4.

Trauma

Penetrating or non-penetrating

5.

Infection of liver tumour or cyst

3

Clinical features:

Patients are generally ill with fever, and sometimes

rigors and weight loss

. Abdominal pain is

the most

common symptom and is usually in the right upper

quadrant, sometimes with radiation to the right

shoulder

.

The pain may be pleuritic in nature.

Tender

hepatomegaly is found in more than 50%

of patients.

Mild

jaundice may be present, becoming severe if large

abscesses cause biliary obstruction. Atypical presentations

are common and explain the frequency with which

the diagnosis is made only at postmortem. This is a

particular

problem in patients with gradually developing

illnesses or pyrexia of unknown origin without localizing

features.

Necrotic colorectal metastases can be

misdiagnosed as hepatic abscess.

Investigations:

Liver imaging is the most revealing investigation and

shows

90% or more of symptomatic abscesses

.

Needle aspiration under ultrasound guidance confirms the diagnosis and provides pus for culture.

A leukocytosis is

frequently found, plasma ALP activity is usually increased, and the serum albumin is often low

. The chest X-ray may

show a raised right diaphragm and lung collapse, or an effusion at the base of the right lung. Blood cultures are

positive in 50–80%. Abscesses caused by gut-derived organisms require active exclusion of significant colonic

pathology, such as a colonoscopy to exclude colorectal carcinoma.

Management

This includes

prolonged antibiotic therapy and drainage of the abscess

. Associated biliary obstruction and cholangitis

require biliary drainage (preferably endoscopically). Pending the results of culture of blood and pus from the

abscess, treatment should be commenced with a

combination of antibiotics such as ampicillin, gentamicin and

metronidazole

. Aspiration or drainage with a catheter placed in the abscess under ultrasound guidance is required if

the abscess is large or if it does not respond to antibiotics. Surgical drainage is rarely undertaken,

although hepatic resection may be indicated for a chronic persistent abscess or ‘pseudotumour’

.

Hydatid cysts

Hydatid cysts are caused by

Echinococcus granulosus

infection. They have an outer layer derived from the host, an

intermediate laminated layer and an inner germinal layer. They can be single (Fig. 23.27) or multiple.

Chronic cysts

become calcified

. The cysts

maybe asymptomatic but may present with abdominal pain or a mass

. Peripheral blood

eosinophilia is present in 20% of cases, whilst X-rays may show calcification of the rim of the abscess. CT reliably

shows the cyst(s), and Echinococcus enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA) has 90% sensitivity for hepatic

hydatid cysts

. Rupture or secondary infection of cysts can occur, and a communication with the intrahepatic biliary

tree can then result, with associated biliary obstruction.

All patients should be treated medically with albendazole or

mebendazole prior to definitive therapy

. In the absence of communications with the biliary tree, treatment consists

of percutaneous aspiration of the cyst followed by the injection of 100% ethanol into the cysts and then re aspiration

of the cyst contents (PAIR).

Where there is communication between the cyst and biliary b system, surgical removal

of the intact cyst is the preferred treatment.

Amoebic liver abscesses

Amoebic liver abscesses are caused by

Entamoeba histolytica

infection. Up

to 50% of cases do not have a previous

history of intestinal disease

. Although amoebic liver abscesses are most often found in endemic areas, patients can

present with no history of travel to these places.

Abscesses are usually large, single and located in the right lobe

;

multiple abscesses may occur in advanced disease. Fever and abdominal pain or swelling are the most common

symptoms.

There may not be associated diarrhoea

. Early symptoms may be local discomfort only and malaise; later,

a swinging temperature and sweating may develop, usually without marked systemic symptoms or associated

cardiovascular signs.

An enlarged, tender liver, cough and pain in the right shoulder are characteristic, but symptoms

may remain vague and signs minimal

. A large abscess may penetrate the diaphragm and rupture into the lung, from

where its contents may be coughed up through a hepaticobronchial fistula. Rupture into the pleural or peritoneal

cavity, or rupture of a left lobe abscess in the pericardial sac, is less common but more serious.

4

Investigations The stool and any exudate should be examined at once under the microscope for motile trophozoites

containing red blood cells. Movements cease rapidly as the stool preparation cools. Several stools may need to be

examined in chronic amoebiasis before cysts are found.

Sigmoidoscopy may reveal typical flask-shaped ulcers

, which

should be scraped and examined immediately for E. histolytica. In endemic areas, one-third of the population are

symptomless passers of amoebic cysts.

An amoebic abscess of the liver is suspected on clinical grounds; there is

often a neutrophil leucocytosis and a raised right hemidiaphragm on chest X-ray

. Confirmation is by ultrasonic

scanning.

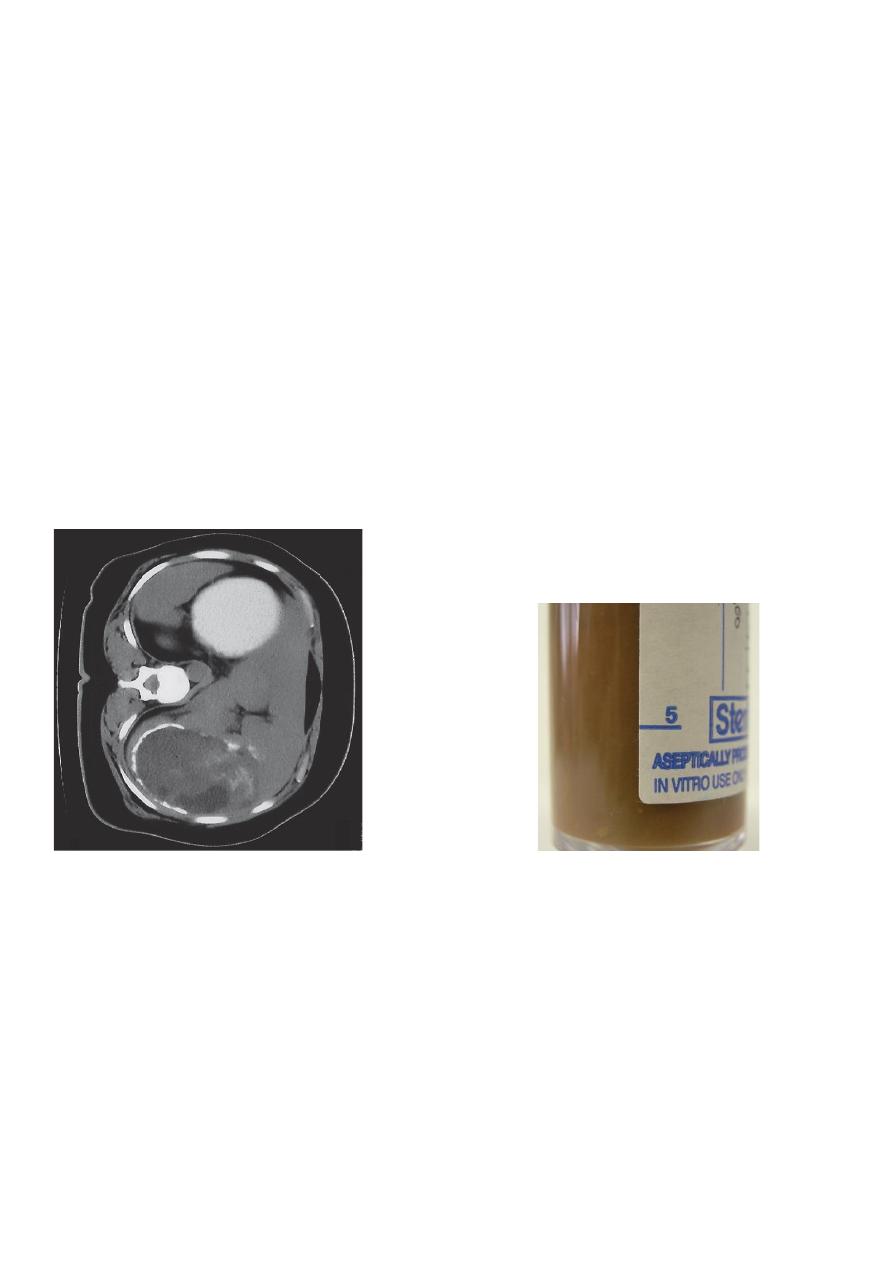

Aspirated pus from an amoebic abscess has the characteristic anchovy sauce or chocolate-brown

appearance but only rarely contains free amoebae (Fig. 13.45B).

Serum antibodies are detectable by

immunofluorescence (carries 99% sensitivity and over 90% specificity) in over 95% of patients with hepatic

amoebiasis and intestinal amoeboma, but in only about 60% of dysenteric amoebiasis. DNA detection by PCR has

been shown to be useful in diagnosis of E. histolytica infections but is not generally available.

Management

Intestinal and early hepatic amoebiasis responds quickly

to

oral metronidazole (800 mg 3 times

daily for 5–10 days)

or other long-acting nitroimidazoles like tinidazole or

ornidazole (both in doses of 2 g daily for 3

days). Nitazoxanide

(500 mg twice daily for 3 days) is an alternative

drug.

Either diloxanide furoate or paromomycin,

in

doses of 500 mg orally 3 times daily for 10 days after treatment,

should be given to eliminate luminal cysts

.

If a

liver abscess is large or threatens to burst, or if

the response to chemotherapy is not prompt, aspiration

is required

and is repeated if necessary. Rupture of an

abscess into the pleural cavity, pericardial sac or

peritoneal cavity

necessitates immediate aspiration or

surgical drainage.

Small serous effusions resolve

without drainage.

Prevention

Personal precautions against contracting amoebiasis

consist of not eating fresh, uncooked vegetables or

drinking unclean water.