Bleeding disorders

TUCOM

Dep. of Medicine

5th year

Dr. Hasan I. Sultan

22- 1- 2019

Bleeding disorders

1. Define haemostasis

2. Explain the stages haemostasis

3. Enumerate the causes bleeding disorders

4. Clarify the clinical assessment of patient with bleeding

disorders

5. Outline the investigations of bleeding disorders

6. Discuss the following conditions: Hereditary

haemorrhagic telangiectasia, Inherited coagulation

disorders and Von Willebrand disease.

7. Review the acquired bleeding disorders

8. Outline the management of bleeding disorders

Haemostasis

Haemostasis is the physiologic balance of procoagulant and

anticoagulant forces that maintain both liquid blood flow

and the structural integrity of the vasculature, but must be

able to form a localized clot at the site of vascular injury in

order to prevent excessive bleeding.

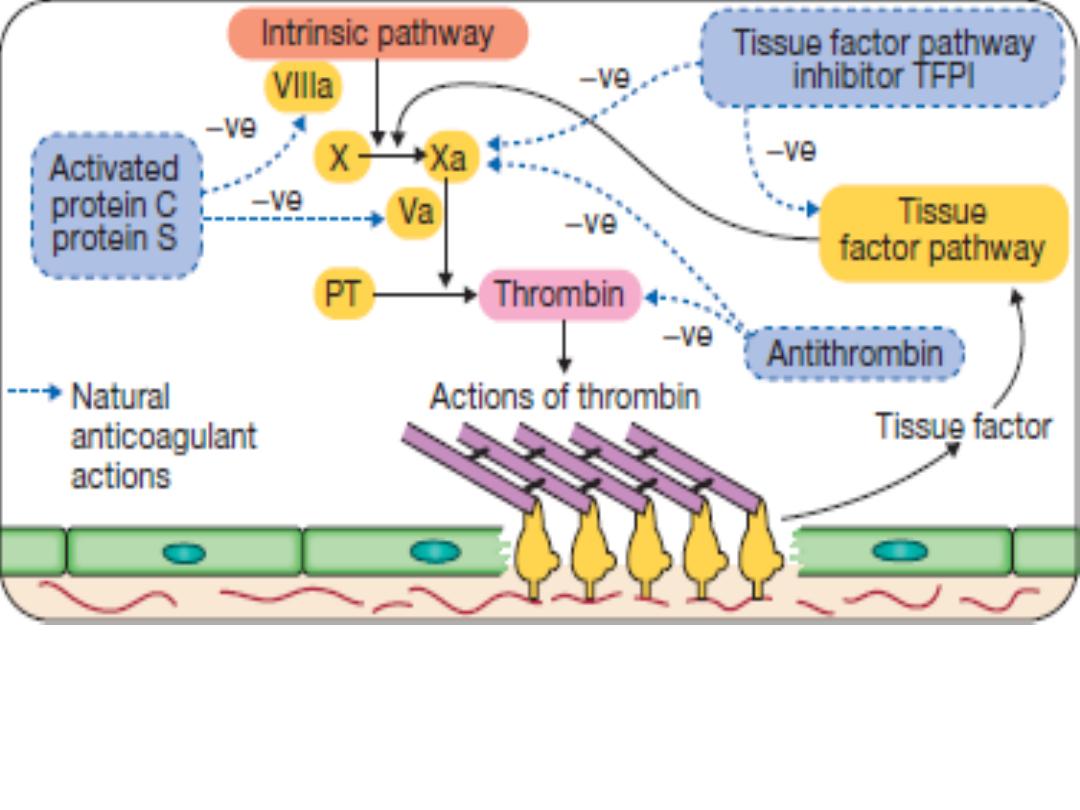

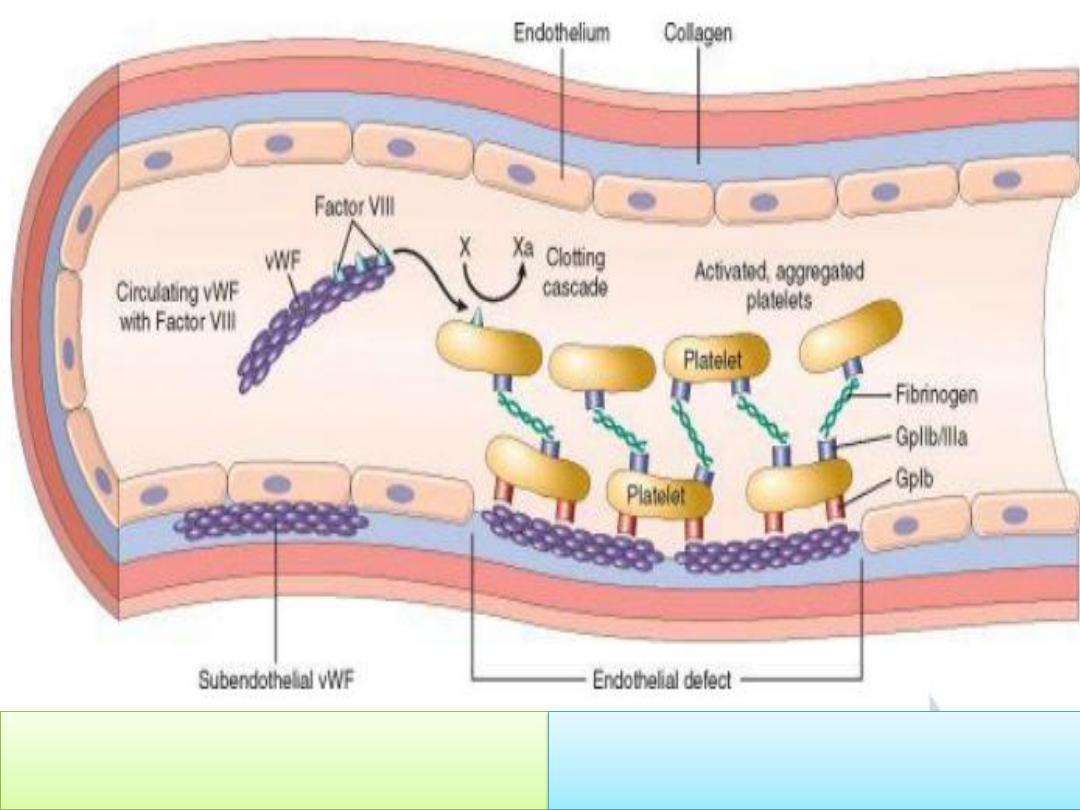

This is achieved by complex interactions between the

vascular endothelium, platelets, coagulation factors, natural

anticoagulants and fibrinolytic enzymes. Dysfunction of any

of these components may result in haemorrhage or

thrombosis.

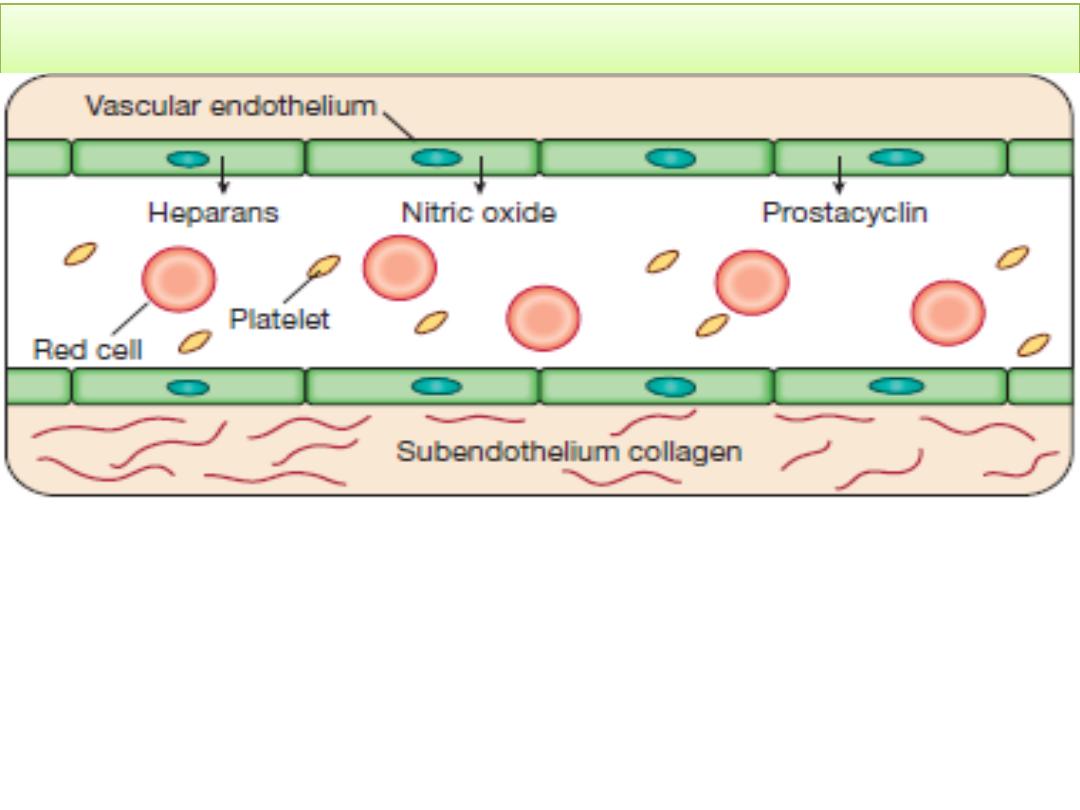

The stages of normal haemostasis

Stage 1

Pre-injury conditions encourage flow. The vascular

endothelium produces substances (including nitric oxide,

prostacyclin and heparans) to prevent adhesion of platelets

and white cells to the vessel wall. Platelets and coagulation

factors circulate in a non-activated state.

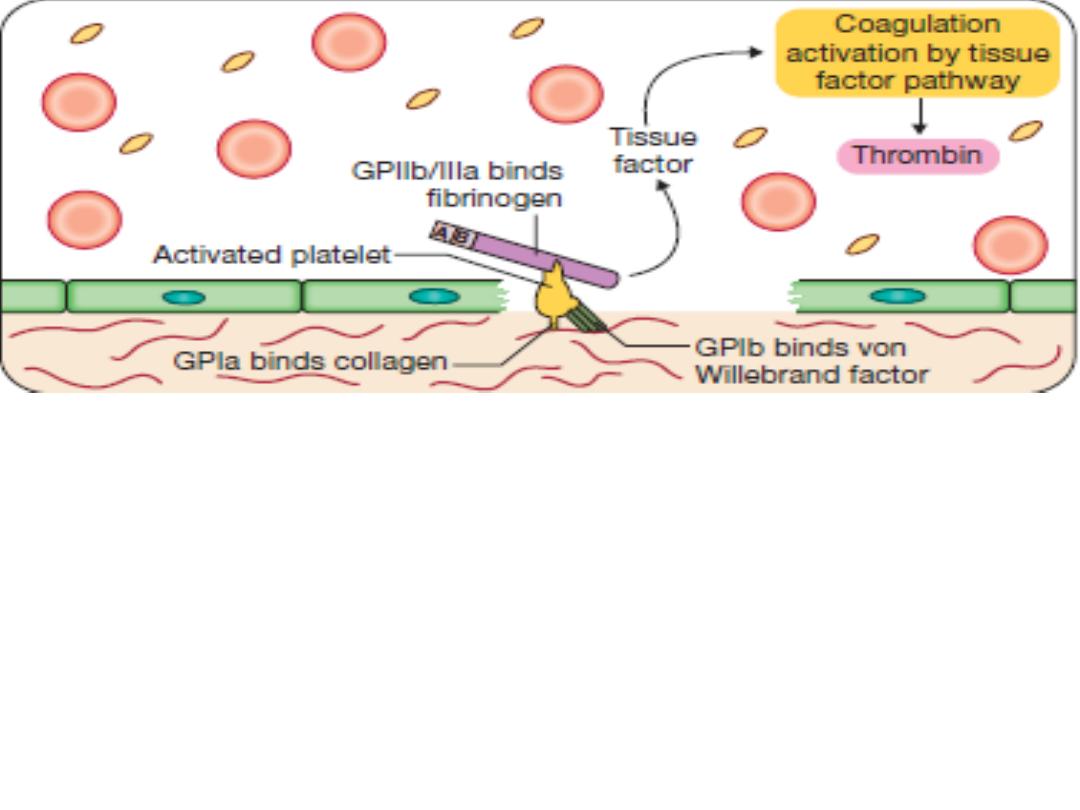

Stage 2

Early haemostatic response: platelets adhere,

coagulation is activated. At the site of injury, the

endothelium is breached, exposing subendothelial collagen.

Small amounts of tissue factor (TF) are released. Platelets

bind by specific receptors (GPIb and GPIIb/IIIa) to von

Willebrand factor and fibrinogen, respectively. Coagulation

is activated by the tissue factor (extrinsic) pathway,

generating small amounts of thrombin.

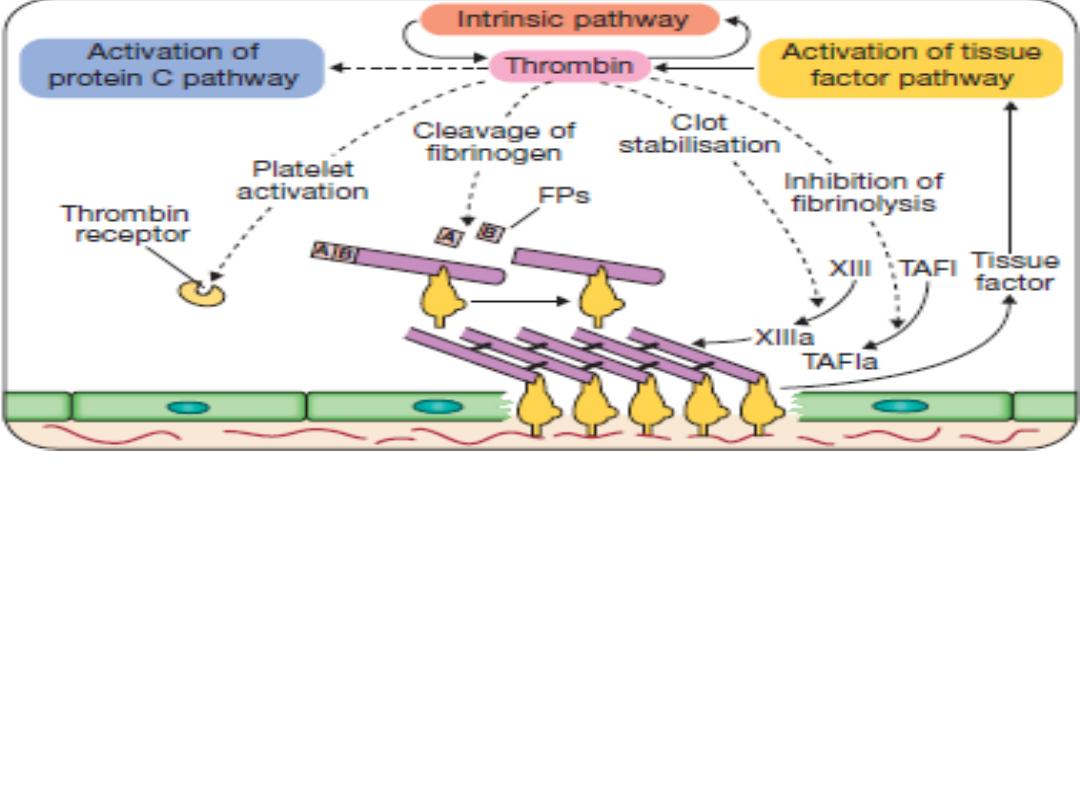

Stage 3

Fibrin clot formation: platelets become activated and

aggregate results in release of the platelet granule contents, enhancing

coagulation further. Thrombin plays a key role in the control of

coagulation: the small amount generated via the TF pathway, the

‘intrinsic’ pathway becomes activated and large amounts of thrombin

are generated. Thrombin directly causes clot formation. Fibrin

monomers are cross-linked by factor XIII, which is also activated by

thrombin. Having had a key role in clot formation and stabilisation.

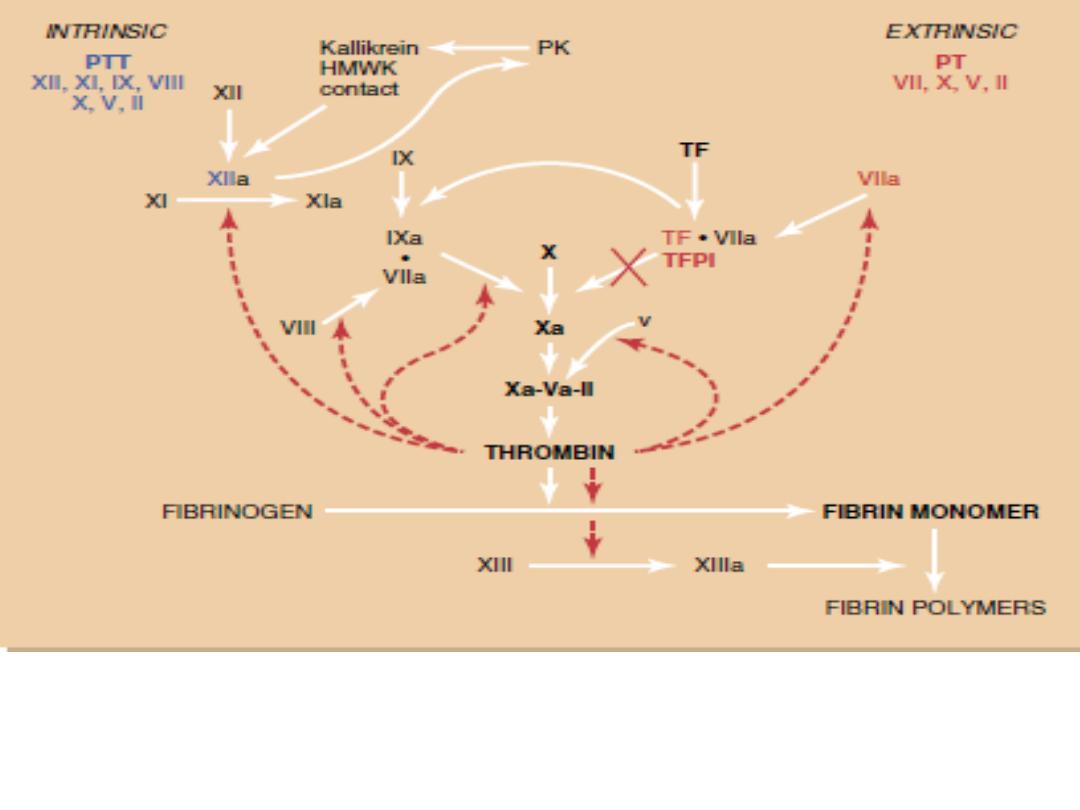

The coagulation cascade. The extrinsic and intrinsic pathways allow monitoring of

anticoagulation by the prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT),

respectively. HMWK, highmolecular- weight kininogen; PK, prekallikrein; TF, tissue

factor; TFPI, tissue factor pathway inhibitor.

The coagulation factors:

• I: Fibrinogen

• II: Thrombin

• III: Tissue factor

• IV: Ca++

• V: Proaccerin / Labile factor

• VI: No longer used

• VII: Proconvertin

• VIII: Antihemophilic factor (AHF)

• IX: Christmas F/ Antihemophilic factor B

• X: Stuart factor

• XI: Plasma thromboplastin antecedent (PTA)/ antihemophilic factor

C

• XII: Hageman factor

• XIII: Fibrin stabilisig factor

• All produce by the liver. Fact. V

and VIII produce also by

platelets and endothelial Cells.

• VIT. K dependent factors: II, VII,

IX and X (inhibited by

warfarin)

Stage 4

Limiting clot formation: natural anticoagulants reverse

activation of coagulation factors. Once haemostasis has been secured,

the propagation of clot is curtailed by anticoagulants: Antithrombin,

protein C (PC) and protein S (PS).

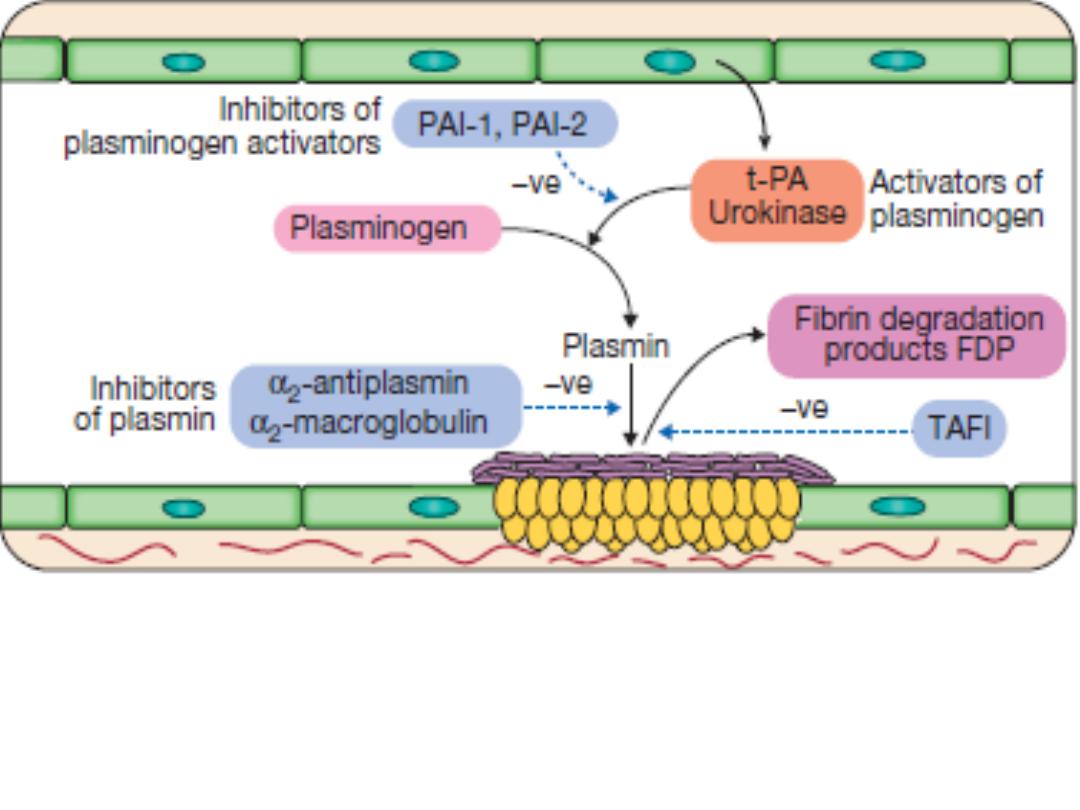

Stage 5

Fibrinolysis: plasmin degrades fibrin to allow vessel

recanalisation and tissue repair. Plasmin, the main fibrinolytic enzyme,

is produced when plasminogen is activated, e.g. by tissue plasminogen

activator (t-PA) or urokinase in the clot. Plasmin hydrolyses the fibrin

clot, producing fibrin degradation products, including the D-dimer.

Bleeding disorders

Normal bleeding is seen following surgery and trauma.

Pathological bleeding occurs when structurally abnormal

vessels rupture or a defect in haemostasis.

Causes:

1- Vascular Causes:

vasculitis, senile purpura, scurvy or

vitamin C deficiency, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

(Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome), pseudoxanthoma elasticum

and Ehlers Danlos syndrome.

2- Deficiency or dysfunction of platelets

3- Coagulation factors disorders

4- Von Willebrand disease

5- Drugs:

excessive antiplatelets, anticoagulant and

fibrinolytic drugs.

Clinical assessment

It is important to consider the following:

1- Site of bleeding:

• Bleeding into muscle and joints, along with

retroperitoneal and intracranial haemorrhage, indicates a

likely defect in coagulation factors.

• Petechiae, purpura, ecchymoses, prolonged bleeding from

superficial cuts, epistaxis and gastrointestinal

haemorrhage indicates thrombocytopenia, a platelet

function disorder or von Willebrand disease.

• Recurrent bleeds at a single site suggest a local structural

abnormality.

2- Duration of history:

to assess whether the disorder is

congenital or acquired.

3- Precipitating causes:

Bleeding arising spontaneously

indicates a more severe defect than bleeding that occurs

only after trauma.

4- Surgery:

Ask about operations.

• Dental extractions, tonsillectomy and circumcision are

stressful tests of the haemostatic system.

• Immediate post-surgical bleeding suggests defective

platelet plug formation and primary haemostasis

• Delayed haemorrhage is more suggestive of a coagulation

defect.

• In postsurgical patients, persistent bleeding from a single

site is more likely to indicate surgical bleeding than a

bleeding disorder.

5- Drugs:

Use of antiplatelets, anticoagulant and fibrinolytic

drugs must be elicited.

6- Family history:

a positive family history may indicates

inherited disorders, like haemophilias or deficiencies of factor

VII, X and XIII, which are recessively inherited.

Examination

• Petechiae, purpura and ecchymosis, in the skin, mucous

membranes, or in the gastrointestinal tract tends to occur

more often in patients with thrombocytopenia, qualitative

platelet defects, vascular abnormalities, and von Willebrand

disease (vWD). Palpable purpura occurs in vasculitis.

• Bleeding in deep organs; joints, or muscles or retroperitoneal

space is more commonly associated with factor deficiencies,

such as hemophilia.

• Telangiectasia of lips and tongue points to hereditary

haemorrhagic telangiectasia.

• Underlying associated systemic illness such as a

haematological or other malignancy, liver disease, renal

failure, connective tissue disease.

Vessel wall abnormalities

1. Congenital, such as hereditary haemorrhagic

telangiectasia

2. Acquired, as in a vasculitis or scurvy

Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) or Osler-

Weber- Rendu syndrome

It is an autosomal dominant inherited condition

Telangiectasia and small aneurysms are found on the

fingertips, face and tongue, and in the nasal passages, lung

and gastrointestinal tract.

large pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (PAVMs) that

cause arterial hypoxaemia due to a right-to-left shunt. These

predispose to paradoxical embolism, resulting in stroke or

cerebral abscess.

Patients present either with recurrent bleeds, particularly

epistaxis, or with iron deficiency due to occult GI bleeding.

Treatment:

• Can be difficult because of the multiple bleeding points

• Regular iron therapy often allows the marrow to

compensate for blood loss.

• Local cautery or laser therapy may prevent single lesions

from bleeding.

Platelet disorders (previous lecture)

Coagulation disorders

• Congenital: X-linked like Haemophilia A and B. Autosomal

like Von Willebrand disease

• Acquired: may be due to under-production (e.g. in liver

failure), increased consumption (e.g. in disseminated

intravascular coagulation) or inhibition of function such as

heparin therapy or inhibition of synthesis such as warfarin

therapy.

Haemophilia A

Factor VIII deficiency resulting in haemophilia A affects

1/10 000 individuals. It is the most common congenital

coagulation factor deficiency. Factor VIII is primarily

synthesised by the liver and endothelial cells, and has a half-

life of about 12 hours. It is protected from proteolysis in the

circulation by binding to von Willebrand factor (vWF).

Genetics

It is X-linked recessive disease. Thus all daughters of

haemophiliacs are obligate carriers and they, in turn, have a

1 in 4 chance of each pregnancy resulting in the birth of an

affected male.

All family members have the same factor VIII gene mutation

and a similarly severe or mild phenotype.

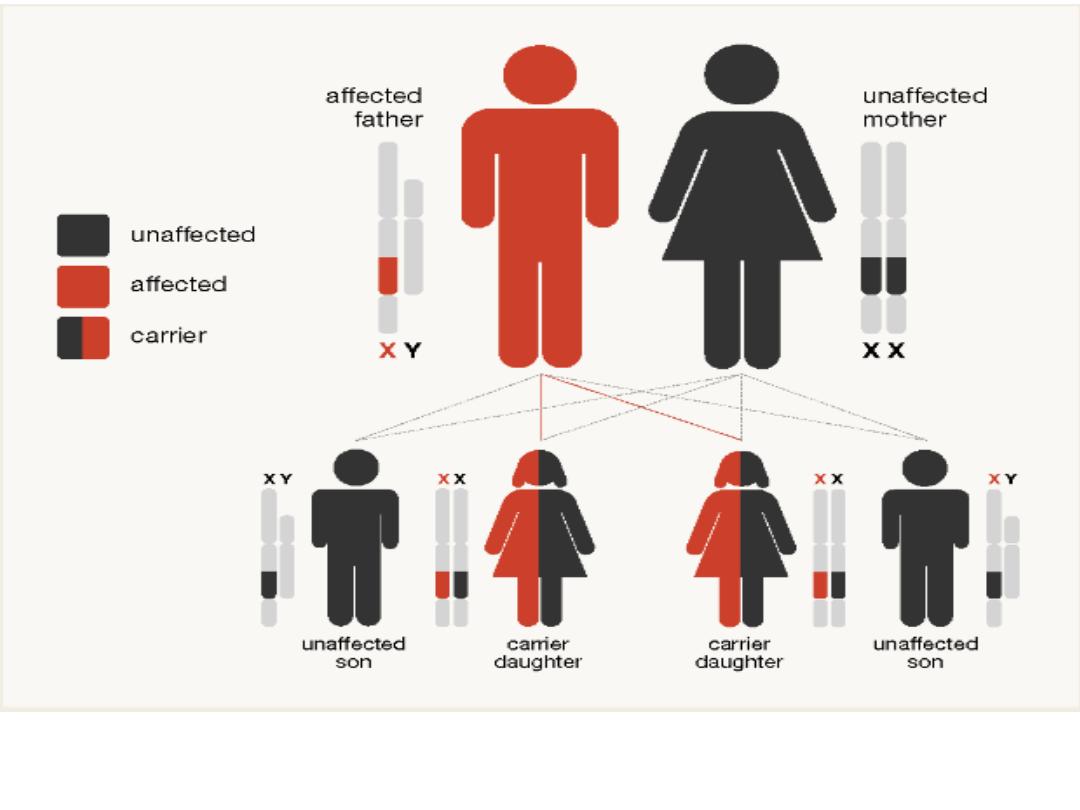

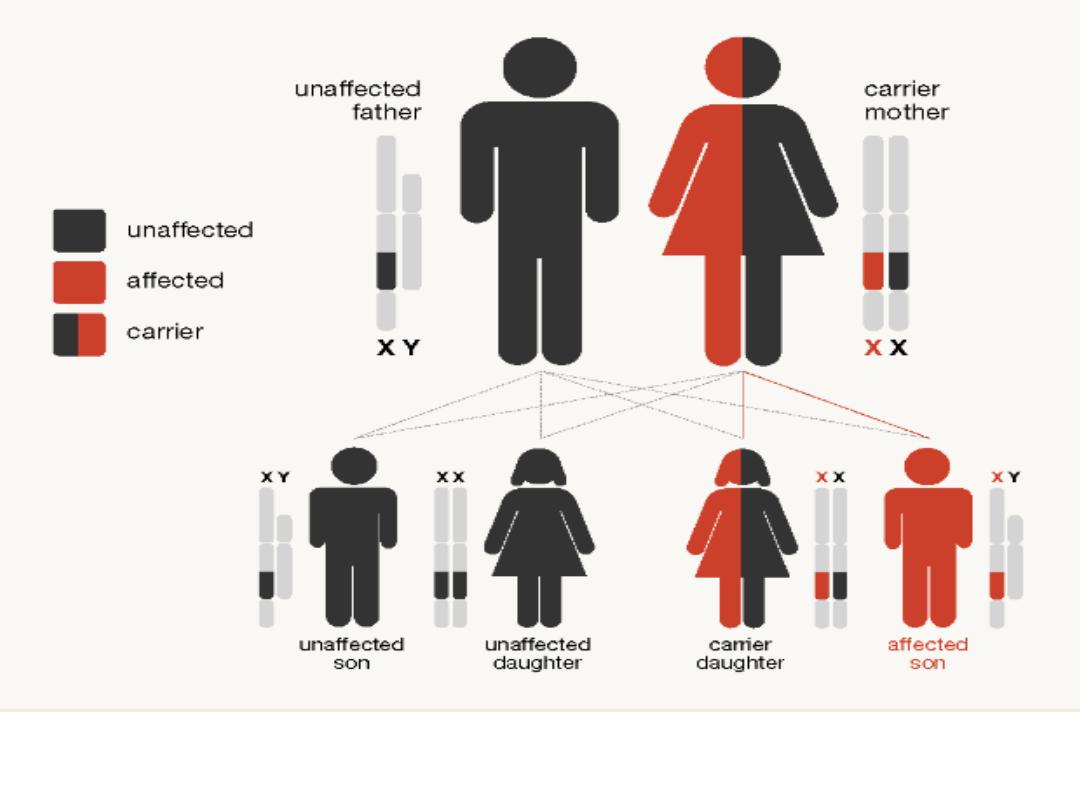

Inherited bleeding disorders

Inheritance of haemophilia in the case of an affected father and a

mother who is not a haemophilia carrier.

Inheritance of haemophilia in the case of a 'carrier' mother (with one

copy of the haemophilia gene) and a father without haemophilia

Clinical features

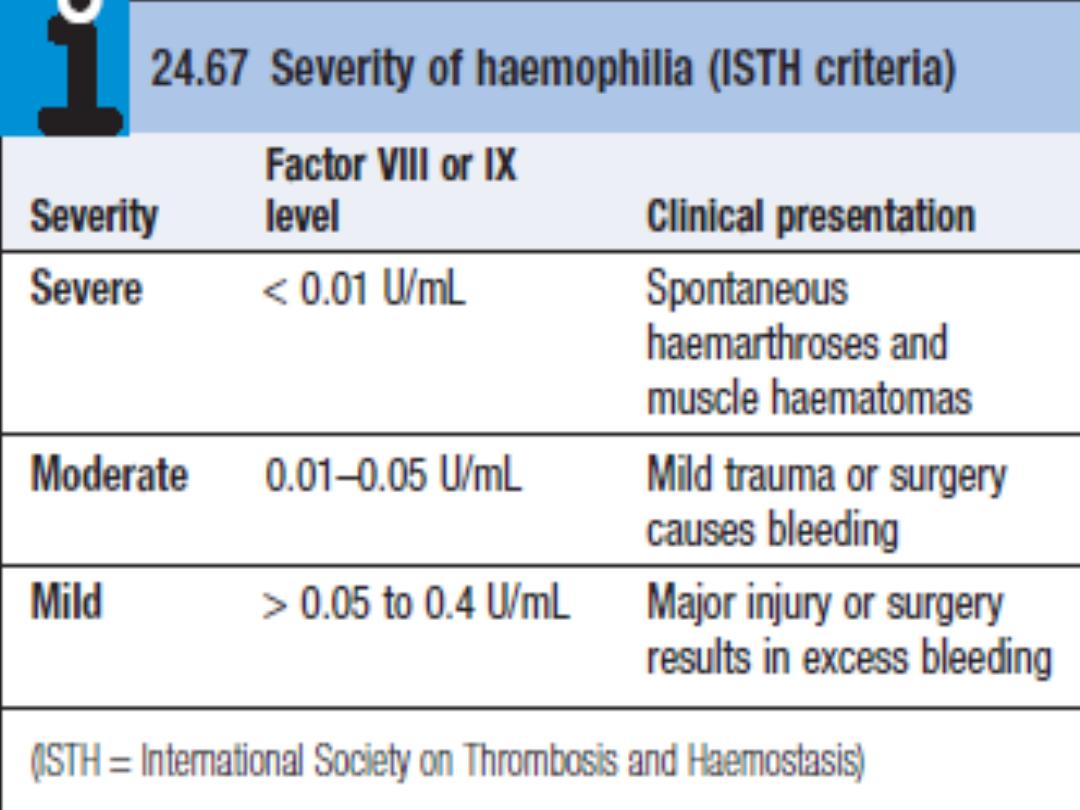

C/F closely related to residual factor VIII levels:

• Severe haemophilia (< 1% of normal factor VIII levels)

present with spontaneous bleeding into skin, muscle and

joints. Retroperitoneal and intracranial bleeding is also a

feature. Babies with severe haemophilia have an

increased risk of intracranial haemorrhage.

• Moderate and mild haemophilia (factor VIII levels 1–40%)

present with the same pattern of bleeding, but usually

after trauma or surgery.

Bleeding is typically into large joints, especially knees,

elbows, ankles and hips. Muscle haematomas are also

characteristic, most commonly in the calf and psoas

muscles.

Acute hemarthrosis of the knee is a common complication of

hemophilia. It may be confused with acute infection unless the

patient's coagulation disorder is known, because the knee is hot, red,

swollen, and painful

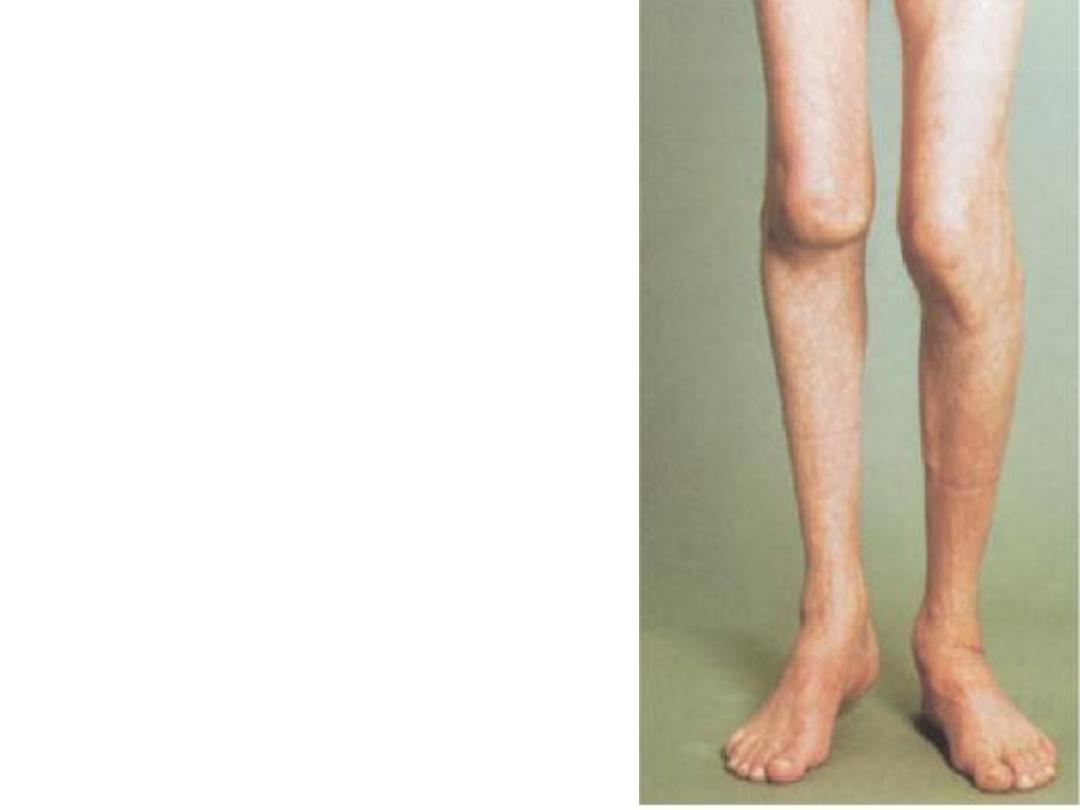

Severe chronic arthritis in

hemophilia. The knee is the most

commonly affected joint. Both

knees are severely deranged in

this patient. Note that he is

unable to stand with both feet flat

on the floor.

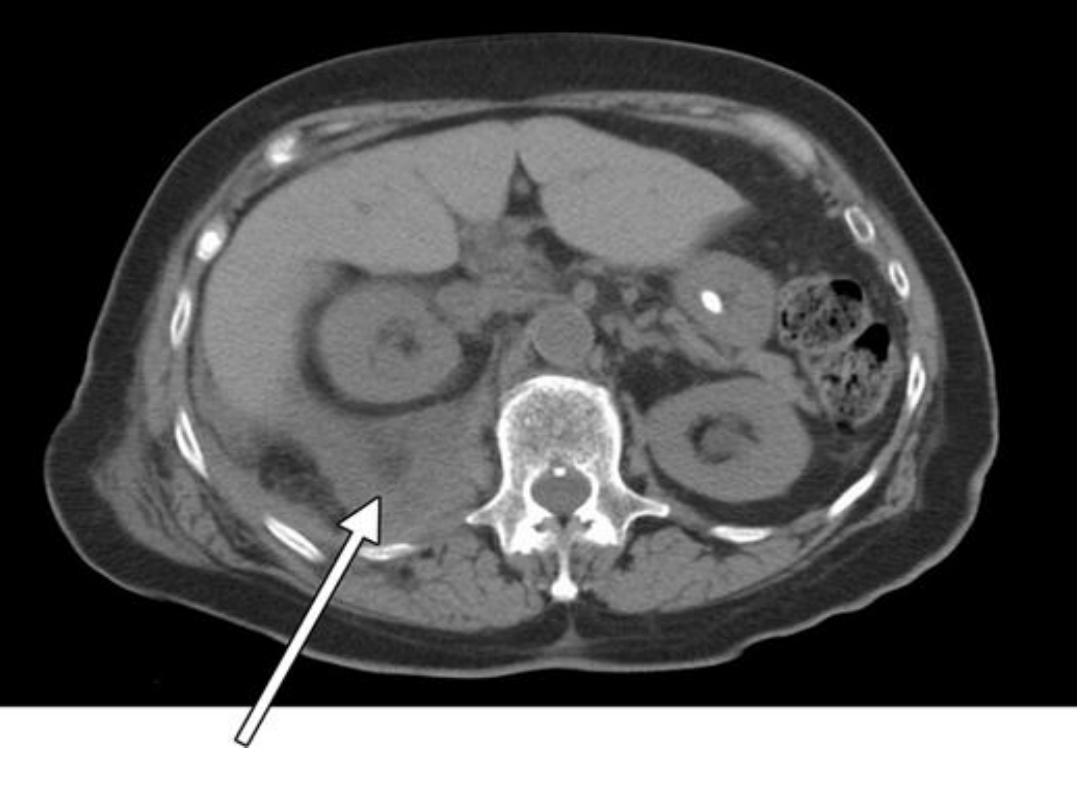

Right retroperitoneal hematoma displacing the kidney anteriorly

Diagnosis

Is confirmed by detection of significantly reduced factor

VIII (hemophilia A) or IX (hemophilia B) activities in the

plasma of:

• Male babies born into families known to be affected by

hemophilia or

• Male children who present with excessive bruising or

bleeding at the time of circumcision

• When intramuscular injections of immunizing vaccinations

are administered, or after trauma during the toddler

years.

prolongation of aPTT.

Management

In severe haemophilia A, bleeding episodes should be

treated by raising the factor VIII level, usually by intravenous

infusion of factor VIII concentrate. Factor VIII concentrates

are freeze-dried and stable at 4°C and can therefore be

stored in domestic refrigerators, allowing patients to treat

themselves at home at the earliest indication of bleeding.

Resting of the bleeding site by either bed rest or a splint

reduces continuing haemorrhage. Once bleeding has settled,

the patient should be mobilised with physiotherapy.

The vasopressin receptor agonist DDAVP raises the vWF and

factor VIII levels by 3–4-fold, which is useful in arresting

bleeding in patients with mild or moderate haemophilia A.

INJURY

FACTOR VIII INITIAL DOSE

(U/kg)*

FACTOR IX INITIAL

DOSE (U/kg)†

Dental prophylaxis

15-25

20-30

Hemarthrosis

15-25

30-50

Muscle hematoma

15-25

30-50

Trauma or surgery

50

100

*

Dosing intervals should be based on a Factor VIII half-life of about 12 hours.

Maintenance doses of one half the listed dose may be additionally provided

at these intervals.

†Dosing intervals should be based on a Factor IX half-life of about 18 to 24

hours. Maintenance doses of one half the listed dose may be additionally

provided at these intervals.

FACTOR REPLACEMENT GUIDELINES FOR HEMOPHILIA A

AND B

Complications

Complications of hemophilia:

Osteoarthrosis. A large psoas bleed may extend to compress

the femoral nerve. Calf haematomas causing a compartment

syndrome with subsequent contraction and shortening of

the Achilles tendon.

Complications of coagulation factor therapy:

• Infection with HIV and hepatitis viruses HBV and HCV.

• Development of anti-factor VIII antibodies ( 20% of severe

haemophiliacs). Such antibodies rapidly neutralise

therapeutic infusions, making treatment relatively

ineffective. Infusions of activated clotting factors, e.g. VIIa

or factor VIII inhibitor bypass activity (FEIBA), may stop

bleeding.

Haemophilia B (Christmas disease)

• It is X-linked recessive disease result in a reduction of the

plasma factor IX level

• It is clinically indistinguishable from hemophilia A but is

less common.

• The frequency of bleeding episodes is related to the

severity of the deficiency of the plasma factor IX level.

• Treatment is with a factor IX concentrate, used in much

the same way as factor VIII for hemophilia A. Although

they do not commonly induce inhibitor antibodies (< 1%

patients).

Acquired Hemophilias:

Autoantibody inhibitors can occur

spontaneously in individuals with previously normal

hemostasis (nonhemophiliacs).

Von Willebrand disease:

• Von Willebrand disease is a common but usually mild

bleeding disorder caused by a quantitative (types 1 and 3)

or qualitative (type 2) deficiency of von Willebrand factor

(vWF).

• The gene for vWF is located on chromosome 12 and the

disease is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant,

except in cases of type 2N and type 3, when it is recessive.

• vWF a protein synthesised by endothelial cells and

megakaryocytes, which is involved in both platelet

function and coagulation. It normally forms a multimeric

structure which is essential for its interaction with

subendothelial collagen and platelets.

• vWF acts as a carrier protein for factor VIII; deficiency of

vWF lowers the plasma factor VIII level.

vWF tethers the platelet to

exposed collagen

vWF serves as a carrier protein for

factor VIII

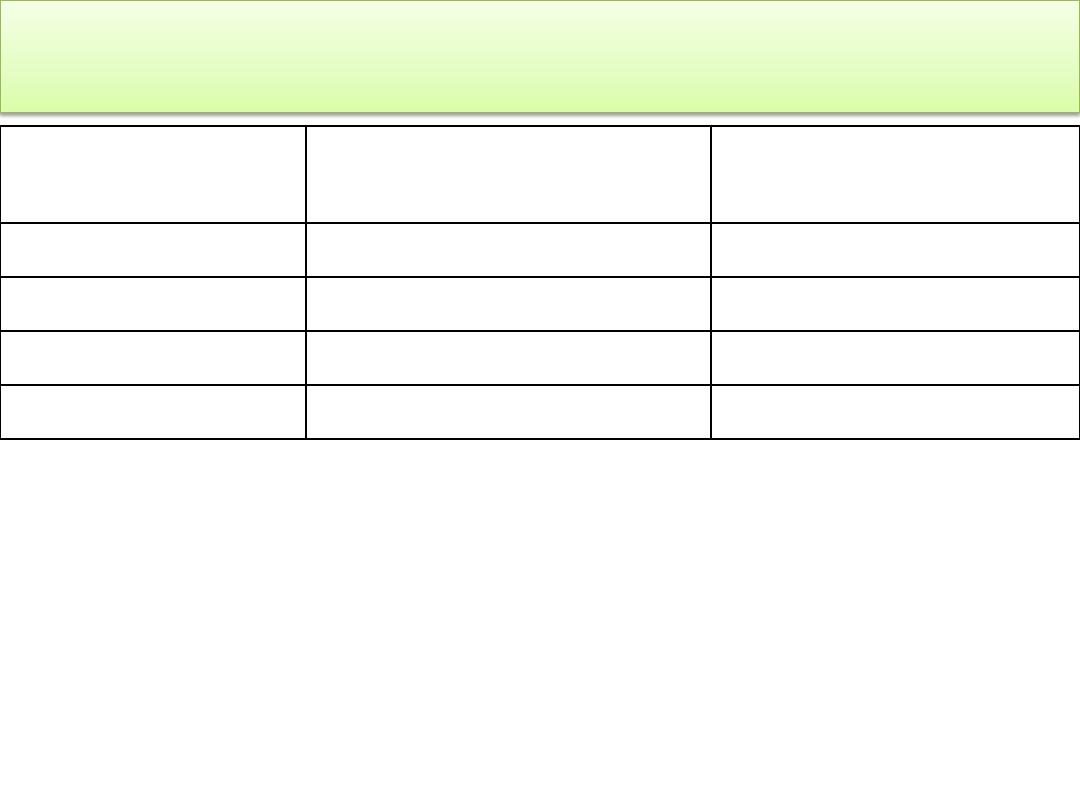

Type

Defect

Inheritance Investigations

1

Partial

quantitative

AD

Parallel decrease in vWF: Ag and

VIII:c

2A

Qualitative

AD

Absent HWM of vWF Ratio of vWF

activity to antigen < 0.7

2B

Qualitative

AD

Reduced HWM of vWF Enhanced

platelet agglutination (RIPA)

2M

Qualitative

AD

Normal multimers of vWF

Abnormal platelets Interactions

2N

Qualitative

AR

Defective binding of vWF to VIII

Low VIII

3

Severe

quantitative

AR or CH

Very low vWF activity and VIII:c

Absent multimers

Classification of von Willebrand disease

CH = compound heterozygote. HWM = high-weight multimers

Most patients with von Willebrand disease have a type 1

disorder, characterised by a quantitative decrease in a

normal functional protein.

Clinical features

Patients present with haemorrhagic manifestations similar

to those in individuals with reduced platelet function.

Superficial bruising, epistaxis, menorrhagia and

gastrointestinal haemorrhage are common.

Within a single family, the disease has variable penetrance,

so that some members may have quite severe and frequent

bleeds, whereas others are relatively asymptomatic.

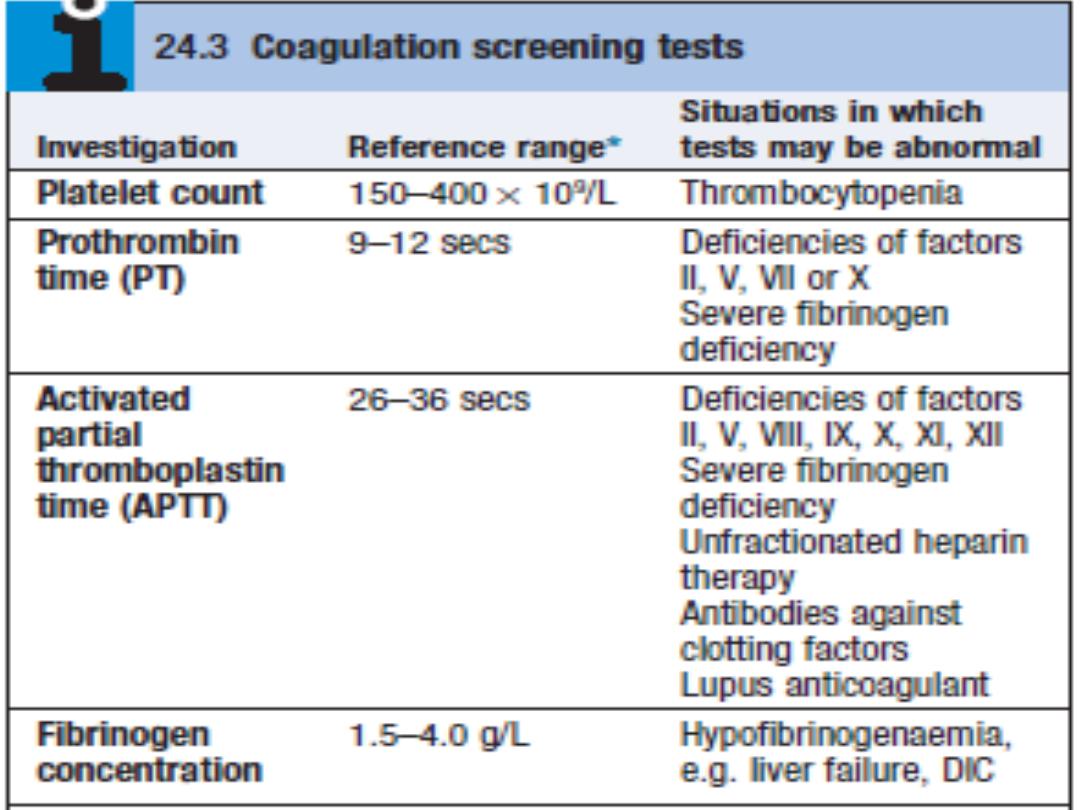

Investigations

Reduced vWF level, activity of vWF and factor VIII.

Prolonged bleeding time and aPTT time, but normal PT time.

In addition, analysis for mutations in the vWF gene is

informative in most cases.

Treatment:

• Mild haemorrhage can be successfully treated by local

means or with DDAVP and tranexamic acid.

• Serious or persistent bleeds, haemostasis can be achieved

with selected factor VIII concentrates which contain

considerable quantities of vWF in addition to factor VIII.

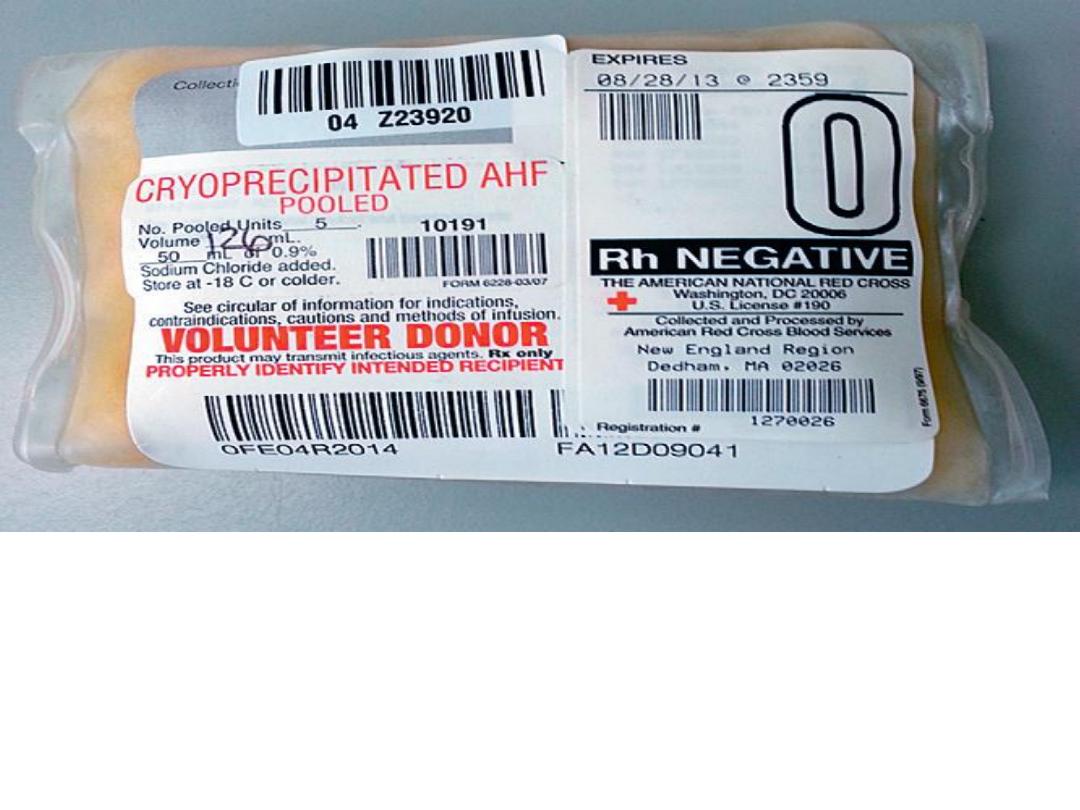

• Cryoprecipitate (contain fibrinogen, factor VIII and VWF)

is used for prophylaxis or treatment of vWD-related

bleeding complications.

A pool of cryoprecipitate: it containing only fibrinogen, fibronectin,

von Willebrand factor, factor VIII, and factor XIII. Individual units of

cryoprecipitate typically contain 10 to 20 mL. Cryoprecipitate is

stored in the frozen state at less than −18° C and must be thawed

before issuing and administration. The shelf life while frozen is 1

year.

Acquired bleeding disorders

• DIC (previous lecture)

• Renal failure (previous lecture)

• Liver failure:

There is reduced hepatic synthesis of factors V,

VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, prothrombin and fibrinogen.

Thrombocytopenia may occur secondary to hypersplenism in

portal hypertension. In cholestatic jaundice, there is reduced

vitamin K absorption, leading to deficiency of factors II, VII, IX

and X.

The PT is a sensitive measure of liver function and becomes

elevated in liver disorders.

Treatment with plasma products or platelet transfusion should

be reserved for acute bleeds or to cover interventional

procedures such as liver biopsy. Vitamin K deficiency can be

readily corrected with parenteral administration of vitamin K.

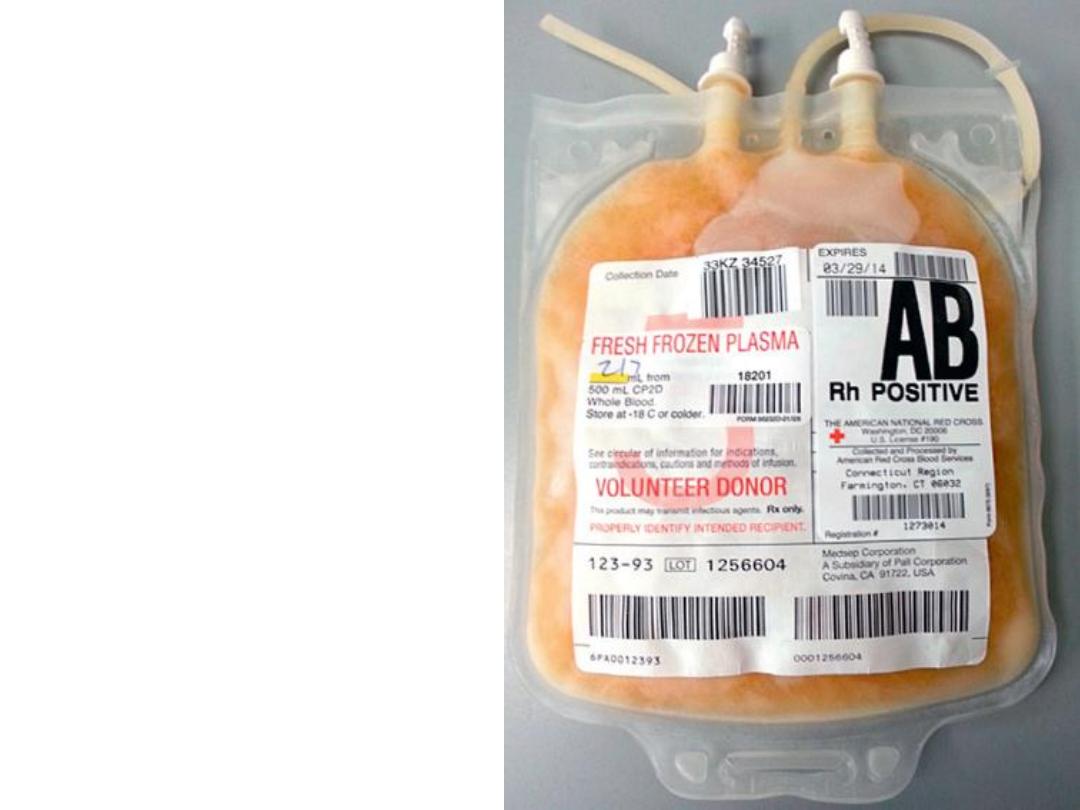

Single unit of fresh-frozen

plasma (FFP). contain a total

volume of about 200 to 250

mL. FFP possesses all

elements found in peripheral

blood plasma, including

coagulation factors, albumin,

complement, and

immunoglobulins, although

they are primarily

administered for coagulation

factor defects. FFP is stored

in the frozen state at less

than −18° C and must be

thawed before issuing and

administration. The shelf life

while frozen is 1 year.

Warfarin therapy bleeding:

warfarin inhibit the vitamin K-dependent carboxylation of factors

II, VII, IX and X in the liver.

Major bleeding is the most common serious side effect of

warfarin and occurs in 1–2% of patients each year. Fatal

haemorrhage, most commonly intracranial, occurs in about

0.25% per annum.

Contraindications to anticoagulation are:

• Recent surgery, especially to eye or CNS

• Pre-existing haemorrhage state, e.g. liver disease,

haemophilia, thrombocytopenia

• Pre-existing structural lesions, e.g. peptic ulcer

• Recent cerebral or gastrointestinal haemorrhage

• Uncontrolled hypertension

• Cognitive impairment

• Frequent falls

The international normalised ratio (INR) is validated only to

assess the therapeutic effect of warfarin. INR is the ratio of

the patient’s PT to that of a normal control, raised to the

power of the international sensitivity index of the

thromboplastin used in the test (ISI, derived by comparison

with an international reference standard material); (patient

PT/mean control PT

ISI

).

warfarin is administered in doses that produce a target INR

of 2.0–3.0 and an increase in bleeding with INR values >4.5.

Treatment of warfarin over-anticoagulation and bleeding:

1- If the INR is above the therapeutic level in asymptomatic

patients whose INR is between 3.5 and 4.5, warfarin should

be withheld until the INR returns to the therapeutic range.

2- If the patient is not bleeding, it may be appropriate to

give a small dose of vitamin K either orally or IV (1–2.5 mg),

especially if the INR is greater than 8.

3- In the event of bleeding, withhold further warfarin.

• Minor bleeding can be treated with 1–2.5 mg of vitamin K

IV.

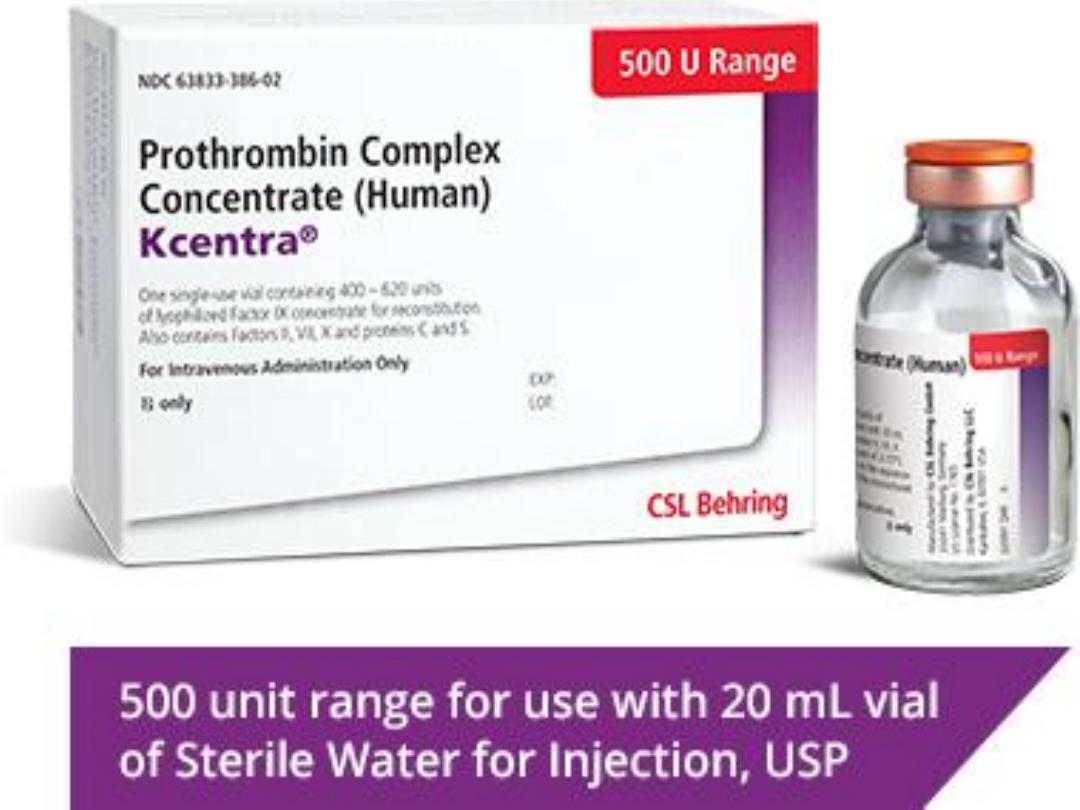

• Major haemorrhage should be treated as an emergency

with vitamin K 5–10 mg slowly IV, combined with

coagulation factor replacement. This should optimally be

a prothrombin complex concentrate (30–50 U/kg) which

contains factors II, VII, IX and X; if that is not available,

fresh frozen plasma (15–30 mL/kg) should be given.

Heparin:

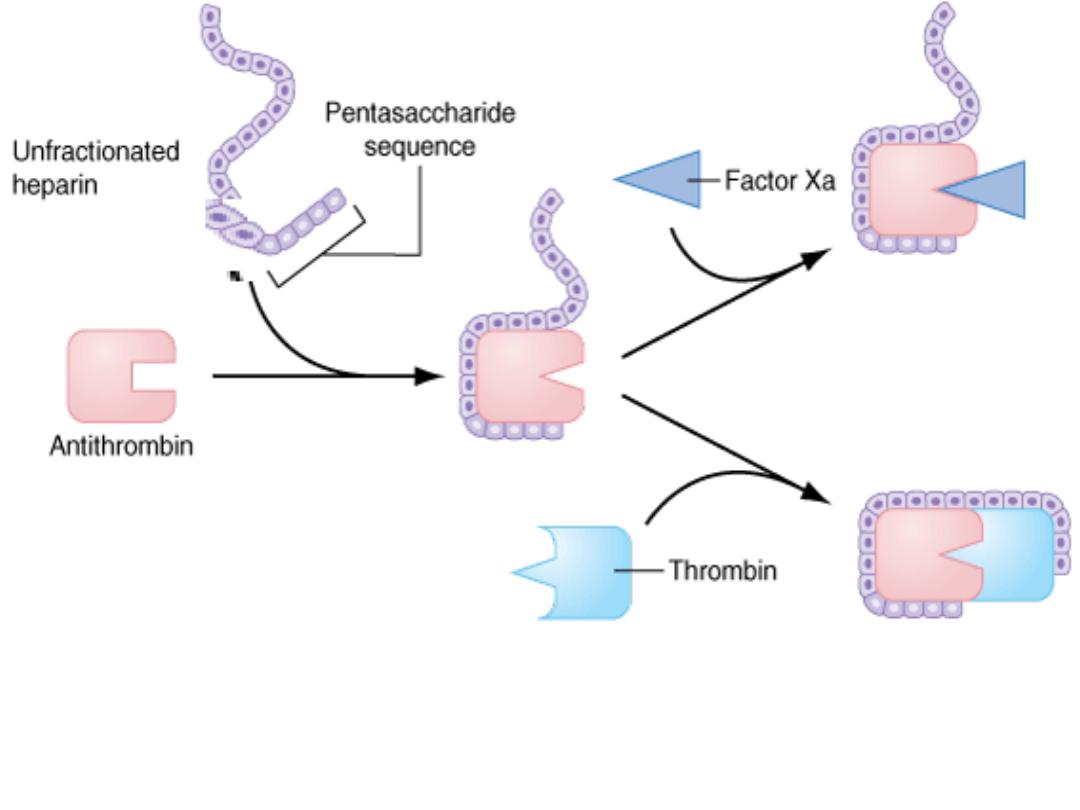

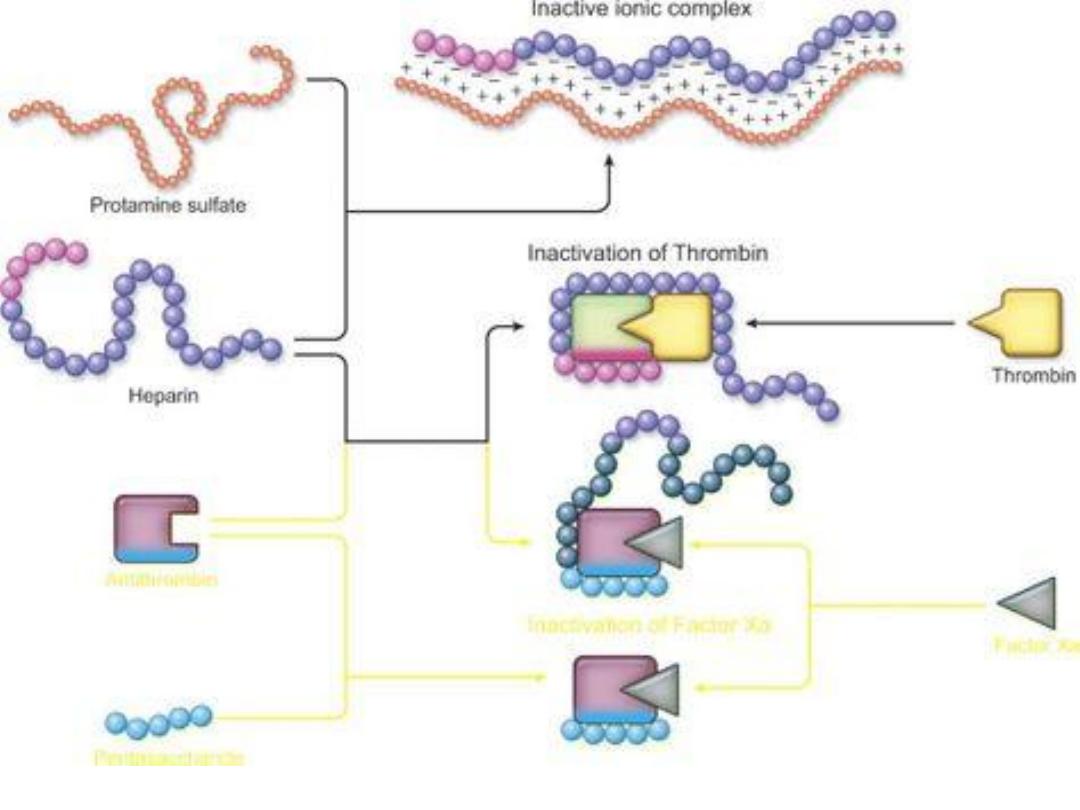

Heparin is a sulfated polysaccharide acts as an anticoagulant

by activating antithrombin (previously known as

antithrombin III) and accelerating the rate at which

antithrombin inhibits clotting enzymes, particularly

thrombin and factor Xa.

Heparin therapy can be monitored using the activated

partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) or anti-factor Xa level.

Therapeutic heparin levels are achieved with a two- to

threefold prolongation of the aPTT.

Heparin-treated patients with serious bleeding can be given

protamine sulfate to neutralize the heparin and result in

protamine-heparin complexes are then cleared. Typically, 1

mg of protamine sulfate neutralizes 100 units of heparin.

Protamine sulfate is given by slow IV infusion.

Heparin binds to antithrombin via its pentasaccharide sequence. This induces a

conformational change in the reactive center loop of antithrombin that accelerates

its interaction with factor Xa. To potentiate thrombin inhibition, heparin must

simultaneously bind to antithrombin and thrombin.

Protamine-heparin complexe

Thanks