BRUCELLOSIS

Brucellosis is an enzootic infection (i.e. endemic in

animals). Although six species of Brucella are known,

only four are important to humans: B. melitensis

(goats, sheep and camels), B. abortus (cattle), B. suis

(pigs) and B. canis (dogs).

B. melitensis is enzootic in the Middle East, Africa,

India, Central Asia and South America. B. abortus is

found in Africa, Asia and South America, and B. suis in

South Asia. B. melitensis causes the most severe

disease; B. suis is often associated with abscess

formation.

Infected animals may excrete brucellae in their milk

for long periods of time and human infection is

acquired by ingesting contaminated milk, cheese,

yoghurt and butter. Uncooked meat and offal may also

spread infection. Animal urine, faeces, vaginal

discharge and uterine products may act as sources of

infection through abraded skin or via splashes and

aerosols to the respiratory tract and conjunctiva.

Clinical features

Brucellae are intracellular organisms that can survive

for long periods within the reticulo-endothelial

system. This explains many of the features of clinical

brucellosis, including the chronicity of the disease and

the tendency to relapse even after adequate

antimicrobial therapy.

Acute illness is characterised by a high swinging

temperature, rigors, sweating, lethargy, headache, and

joint and muscle pains. Occasionally, there is delirium,

abdominal pain and constipation. Physical signs are

non-specific: for example, a palpable spleen or

enlarged lymph nodes. Enlargement of the spleen may

lead to hypersplenism and thrombocytopenia.

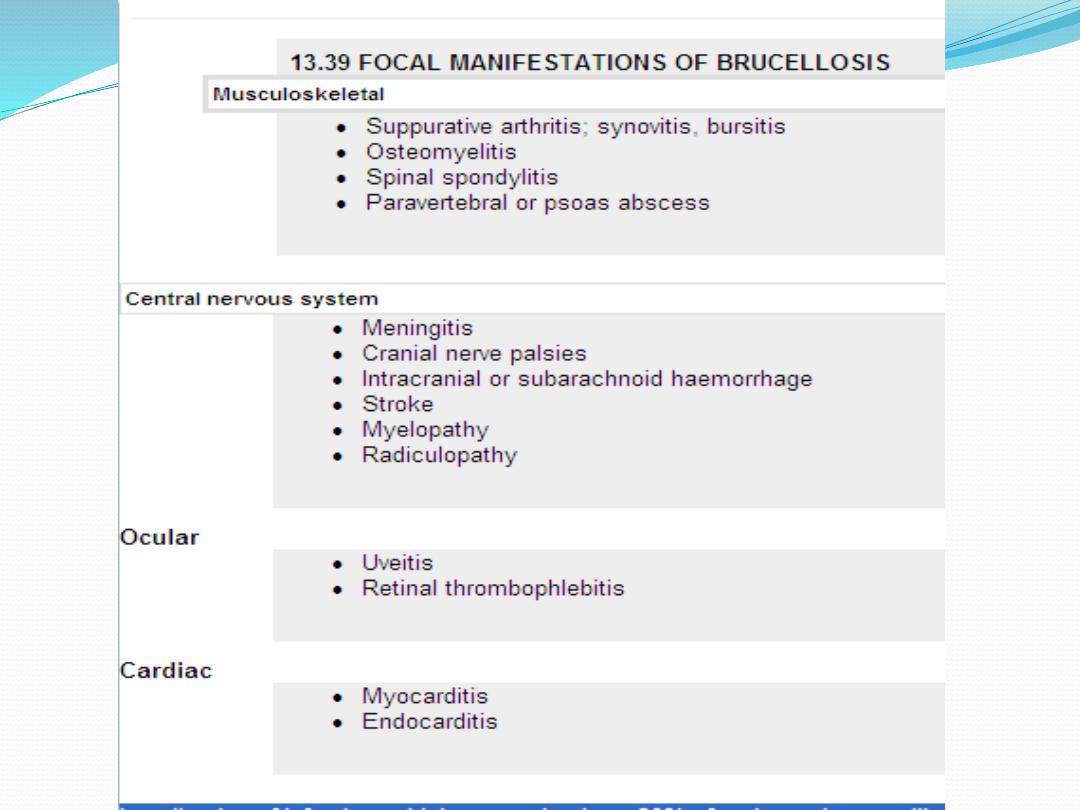

Localisation of infection, which occurs in about 30% of

patients, is more likely if diagnosis and treatment are

delayed.

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of brucellosis depends on the

isolation of the organism. Blood cultures are positive

in 75-80% of infections caused by B. melitensis and

50% of those caused by B. abortus. The non-

radiometric 'Bactec' system gives a good isolation rate,

but if brucellosis is suspected, prolonged incubation

and blind subcultures are recommended. Bone

marrow culture should not be used routinely but may

increase the diagnostic yield, particularly if antibiotics

have been given before specimens are taken. CSF

culture in neurobrucellosis is positive in about 30% of

cases.

World-wide, the serum agglutination test is the

serological technique most commonly employed to

detect brucellosis. The test has many pitfalls and good

quality control is essential. Agglutination should be

carried out to a high dilution (at least 1/640) to avoid

the prozone phenomenon whereby non-agglutinating

IgG and IgA molecules completely block the

agglutinating reaction. Significant agglutination titres

may persist for months or years after recovery and in

endemic areas a single titre of 1/320 or a fourfold rise in

titre is needed to support a diagnosis of acute

infection. The test usually takes several weeks to

become positive but should eventually detect 95% of

acute infections. The pre-treatment of serum with 2-

mercaptoethanol helps to distinguish between IgG

and IgM responses.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) also

identifies IgM and IgG antibodies; IgM decreases

rapidly within the first few months of illness. Specialist

laboratory techniques including the use of the anti-

human globulin (Coombs) test may be necessary to

distinguish chronic disease from past inactive

infection.

Management

Aminoglycosides show synergistic activity with

tetracyclines when used against brucellae. Standard

therapy therefore consists of doxycycline 100 mg 12-

hourly for 6 weeks, with streptomycin 1 g i.m. daily for

the first 2 weeks. The relapse rate with this treatment

is about 5%. An alternative oral regimen consists of

doxycycline 100 mg 12-hourly plus rifampicin 900 mg

(15 mg/kg) daily for 6 weeks, but failure and relapse

rates are higher, particularly with spondylitis.

Rifampicin may antagonise doxycycline activity by

reducing serum levels through enzyme induction.

Chronic illness should be treated for a minimum of 3

months and many authorities would extend this to 6

months, depending upon the condition of the patient

and the result of sequential serological tests. The

optimum therapy for neurobrucellosis is unknown,

and there is no current agreement on the combination

or number of drugs to use. Treatment should continue

for at least 3 months, and longer if CSF pleocytosis

persists.

THANK YOU FOR

LISTENING