SERONEGATIVE

SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIES

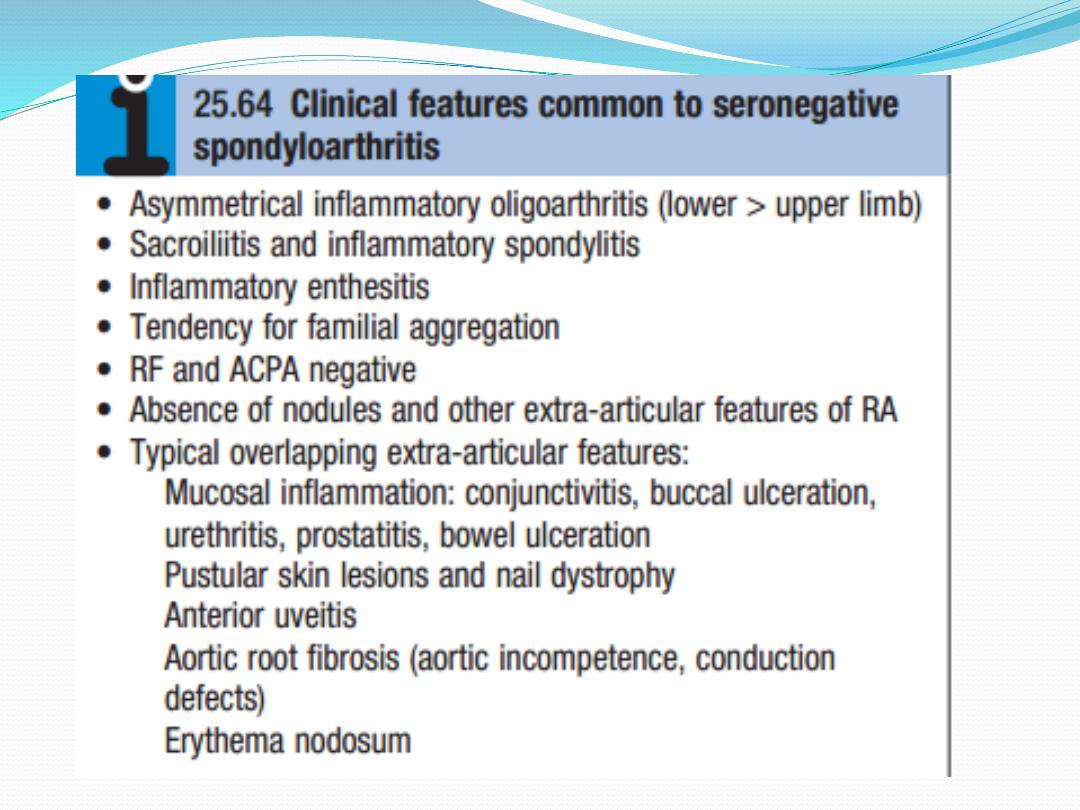

These comprise a group of related inflammatory joint

diseases, which show considerable overlap in their

clinical features and a shared immunogenetic

association with the HLAB27 antigen . They include:

• ankylosing spondylitis

• axial spondyloarthritis

• reactive arthritis, including Reiter’s syndrome

• psoriatic arthritis

• arthropathy associated with inflammatory bowel

disease.

There is a striking association with carriage of the

HLAB27 allele, particularly for ankylosing spondylitis

(>95%) and reactive arthritis (90%), and especially

associated with sacroiliitis, uveitis or balanitis.

Understanding of the cause is incomplete but an

aberrant response to infection is thought to be

involved in genetically predisposed individuals. In

some situations, a triggering organism can be

identified, as in reactive arthritis following bacterial

dysentery or chlamydial urethritis, but in others the

environmental trigger remains obscure. Familial

clustering not only is common to the specific

condition occurring in the proband, but also may

extend to other diseases in the seronegative

spondyloarthopathy group.

Ankylosing spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is characterised by a chronic

inflammatory arthritis predominantly affecting the

sacro iliac joints and spine, which can progress to bony

fusion of the spine. The onset is typically between the

ages of 20 and 30, with a male preponderance of about

3 : 1. In Europe, more than 90% of those affected are

HLAB27positive. The overall prevalence is less than

0.5% in most populations. Over 75% of patients are able

to remain in employment and enjoy a good quality of

life. Even if severe ankylosis develops, functional limita

tion may not be marked as long as the spine is fused in

an erect posture.

Pathophysiology

Ankylosing spondylitis is thought to arise from an as

yet illdefined interaction between environmental

pathogens and the host immune system in genetically

susceptible individuals. Increased faecal carriage of

Klebsiella aerogenes occurs in patients with

established AS and may relate to exacerbation of both

joint and eye disease. Wider alterations in the human

gut microbial environment are increasingly

implicated, which could lead to increased levels of

circulating cytokines such as IL23 that can activate

enthesial or synovial T cells.

The HLAB27 molecule itself is implicated through its

antigen presenting function (it is a class I MHC

molecule) or because of its propensity to form

homodimers that activate leucocytes. HLAB27

molecules may also misfold, causing increased

endoplasmic reticulum stress. This could lead to

inflammatory cytokine release by macrophages and

dendritic cells, thus triggering inflammatory disease.

Clinical features

The cardinal feature is low back pain and early morning

stiffness with radiation to the buttocks or posterior

thighs. Symptoms are exacerbated by inactivity and

relieved by movement. The disease tends to ascend

slowly, ultimately involving the whole spine, although

some patients present with symptoms of the thoracic

or cervical spine. As the disease progresses, the spine

becomes increasingly rigid as ankylosis occurs.

Secondary osteoporosis of the vertebral bodies frequently

occurs, leading to an increased risk of vertebral fracture.

Early physical signs include a reduced range of lumbar

spine movements in all directions and pain on

sacroiliac stressing. As the disease progresses, stiffness

increases throughout the spine and chest expansion

becomes restricted. Spinal fusion varies in its extent

and in most cases does not cause a gross flexion

deformity, but a few patients develop marked kyphosis

of the dorsal and cervical spine that may interfere with

forward vision.

This may prove incapacitating, especially when

associated with fixed flexion contractures of hips or

knees. Pleuritic chest pain aggravated by breathing is

common and results from costovertebral joint

involvement. Plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinitis and

tenderness over bony prominences such as the iliac

crest and greater trochanter may all occur, reflecting

inflammation at the sites of tendon insertions

(enthesitis).

Up to 40% of patients also have peripheral arthritis.

This is usually asymmetrical, affecting large joints such

as the hips, knees, ankles and shoulders. In about 10%

of cases, involvement of a peripheral joint may

antedate spinal symptoms, and in a further 10%,

symptoms begin in childhood, as in the syndrome of

oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

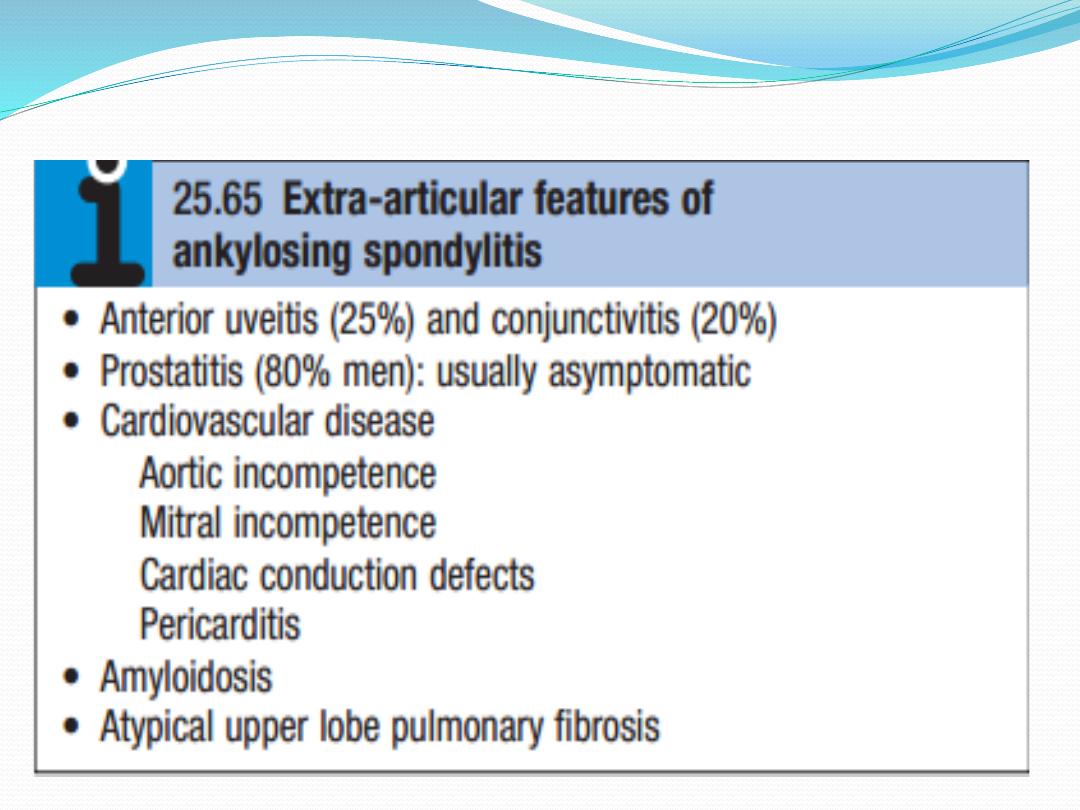

Fatigue is a major complaint and may result from both

chronic interruption of sleep due to pain, and chronic

systemic inflammation with direct effects of

inflammatory cytokines on the brain. Acute anterior

uveitis is the most common extraarticular feature,

which occasionally precedes joint disease. Other extra-

articular features are occasionally observed but are

rare.

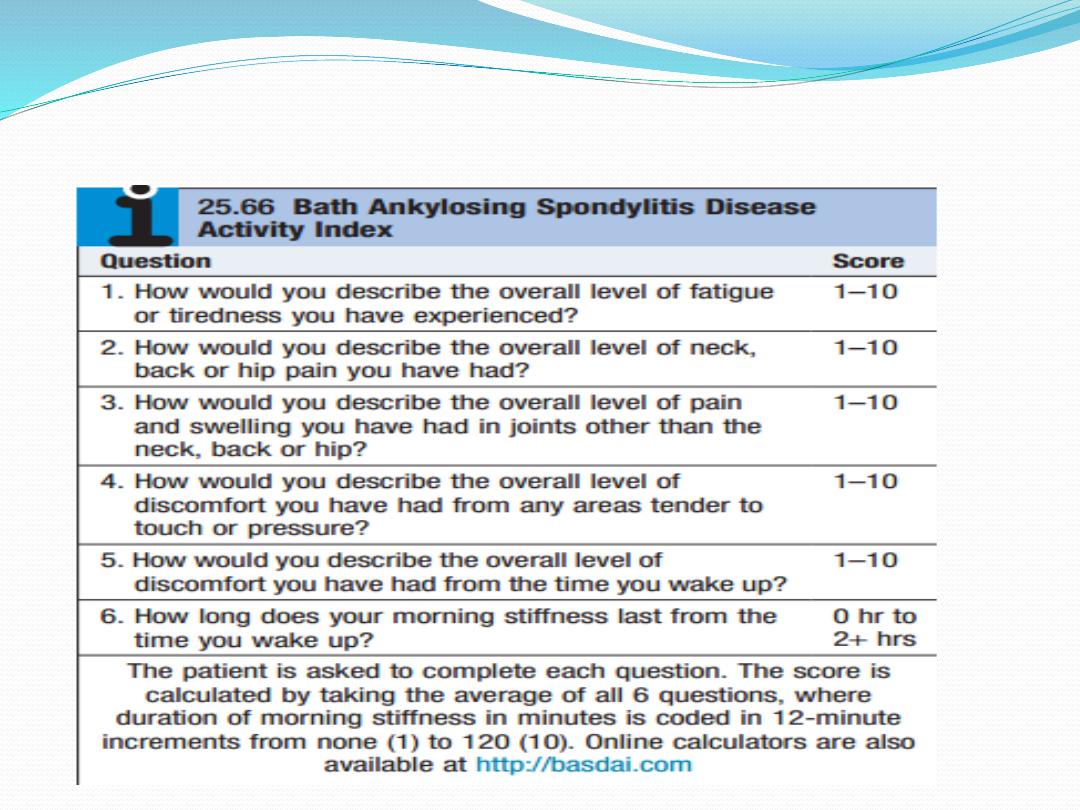

This is important in assessing eligibility for biological treatment.

Investigations

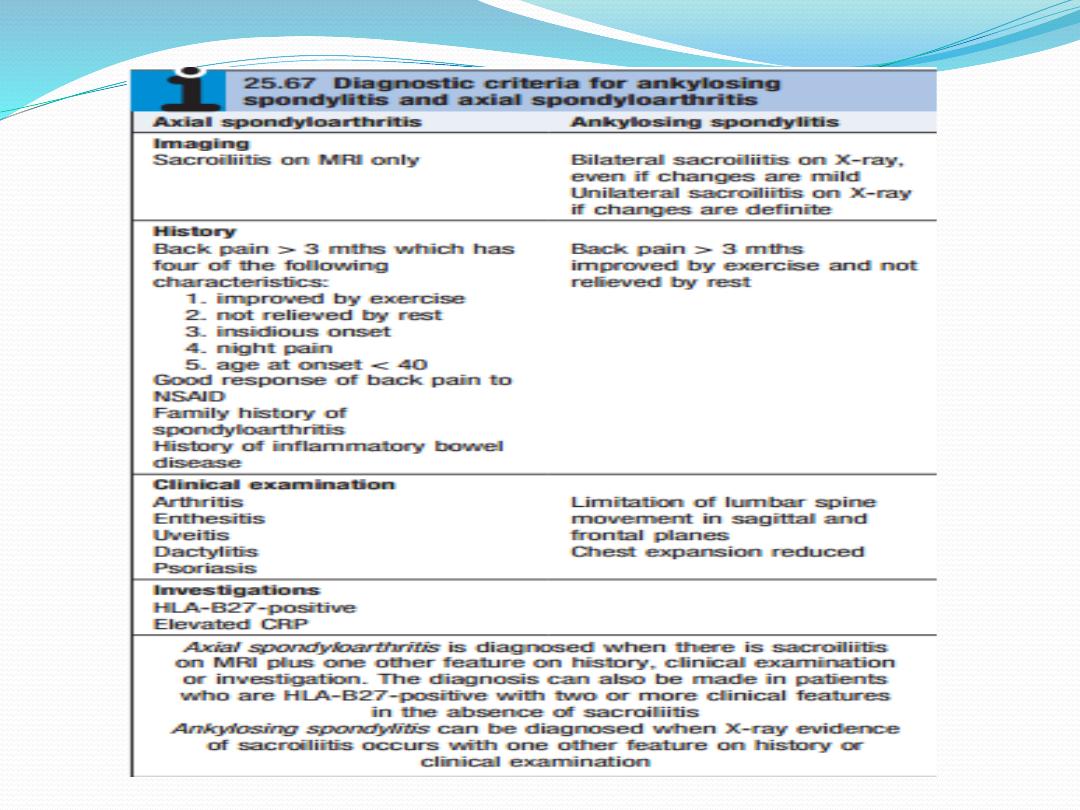

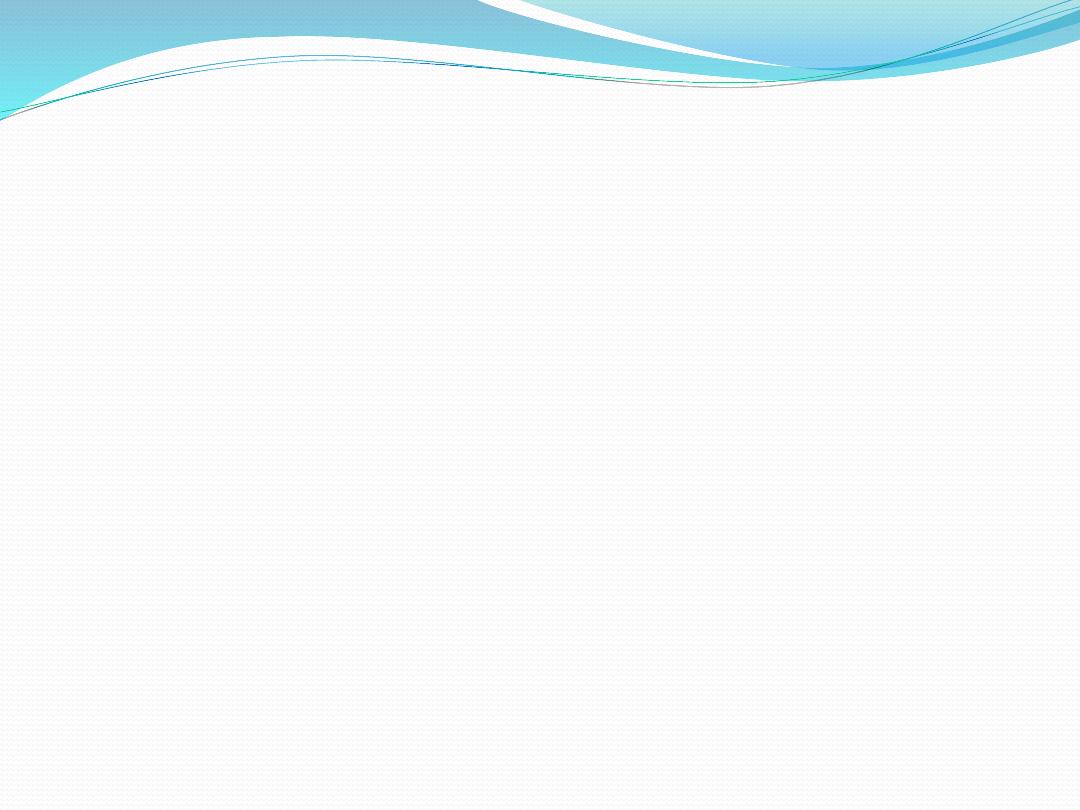

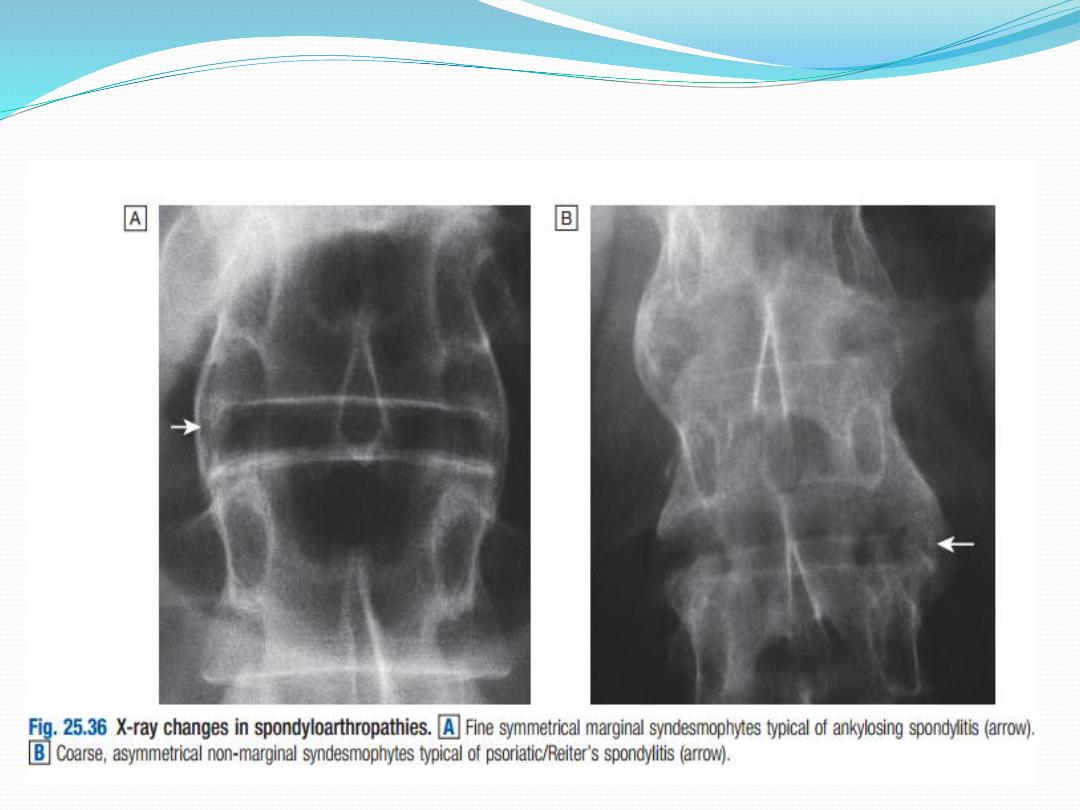

In established AS, radiographs of the sacroiliac joint

show irregularity and loss of cortical margins,

widening of the joint space and subsequently sclerosis,

joint space narrowing and fusion. Lateral

thoracolumbar spine Xrays may show anterior

‘squaring’ of vertebrae due to erosion and sclerosis of

the anterior corners and periostitis of the waist.

Bridging syndesmophytes may also be seen. These are

areas of calcification that follow the outermost fibres

of the annulus.

In advanced disease, ossification of

the anterior longitudinal ligament

and facet joint fusion may also be

visible. The combination of these

features may result in the typical

‘bamboo’ spine.

Erosive changes may be seen in the symphysis pubis,

the ischial tuberosities and peripheral joints.

Osteoporosis and atlantoaxial dislocation can occur as

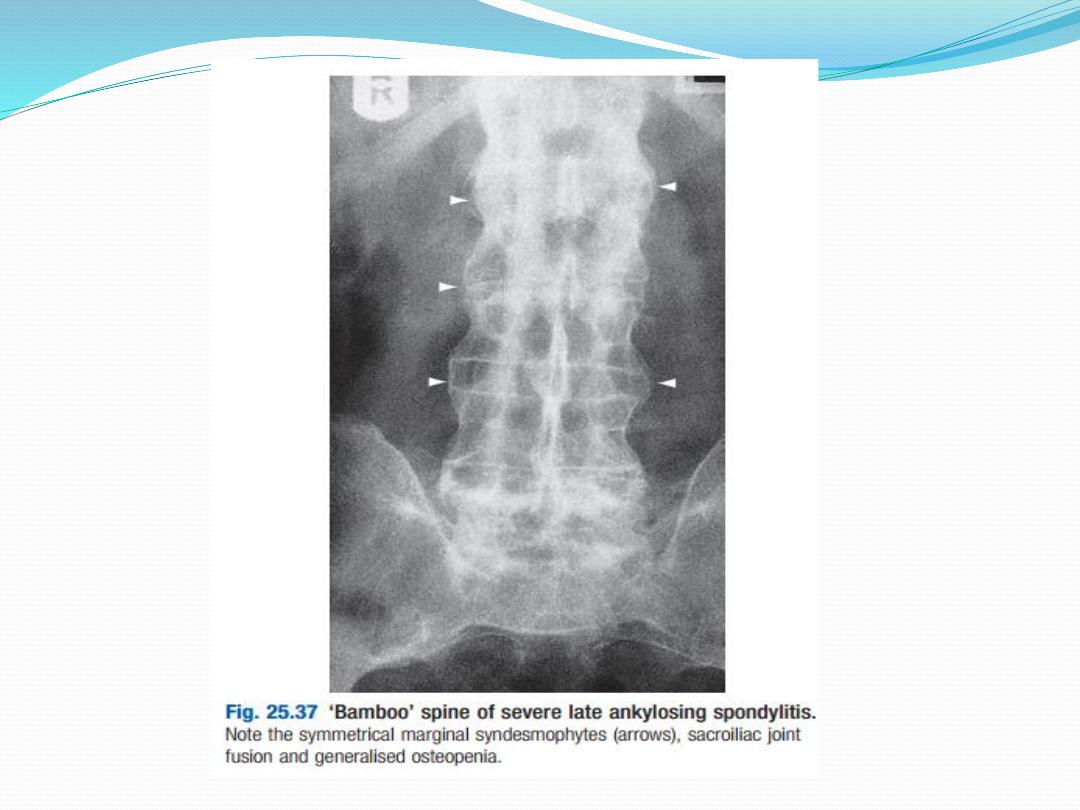

late features. Patients with early disease can have

normal Xrays, and if clinical suspicion is high, MRI

should be performed. This is much more sensitive for

detection of early sacroiliitis than Xray and can also

detect inflammatory changes in the lumbar spine.

The ESR and CRP are usually raised in active disease

but may be normal. Testing for HLAB27 can be

helpful, especially in patients with back pain

suggestive of an inflammatory cause, when other

investigations have yielded equivocal results.

Autoantibodies such as RF, ACPA and ANA are

negative.

Management

The aims of management are to relieve pain and stiff

ness, maintain a maximal range of skeletal mobility

and avoid the development of deformities. Education

and appropriate physical activity are the cornerstones

of management. Early in the disease, patients should

be taught to perform daily back extension exercises,

including a morning ‘warmup’ routine, and to

punctuate prolonged periods of inactivity with regular

breaks.

Swimming is ideal exercise. Poor posture must be

avoided. NSAIDs and analgesics are often effective in

relieving symptoms and may alter the underlying

course of the disease. A longacting NSAID at night is

helpful for alleviation of morning stiffness. Peripheral

arthritis can be treated with methotrexate or

sulfasalazine, but these drugs have no effect on axial

disease.

AntiTNF therapy should be considered in patients who

are inadequately controlled on standard therapy with a

BASDAI score of ≥4.0 and a spinal pain score of ≥4.0.

AntiTNF therapy frequently improves symptoms but

has not been shown to prevent ankylosis or alter

natural history of the disease. Other biological

interventions using agents developed for RA have been

disappointing, suggesting fundamental differences in

disease pathogenesis.

Local corticosteroid injections can be useful for

persistent plantar fasciitis, other enthesopathies and

peripheral arthritis. Oral corticosteroids may be

required for acute uveitis but do not help spinal

disease. Severe hip, knee or shoulder restriction may

require surgery. Total hip arthroplasty has largely

removed the need for difficult spinal surgery in those

with advanced deformity.

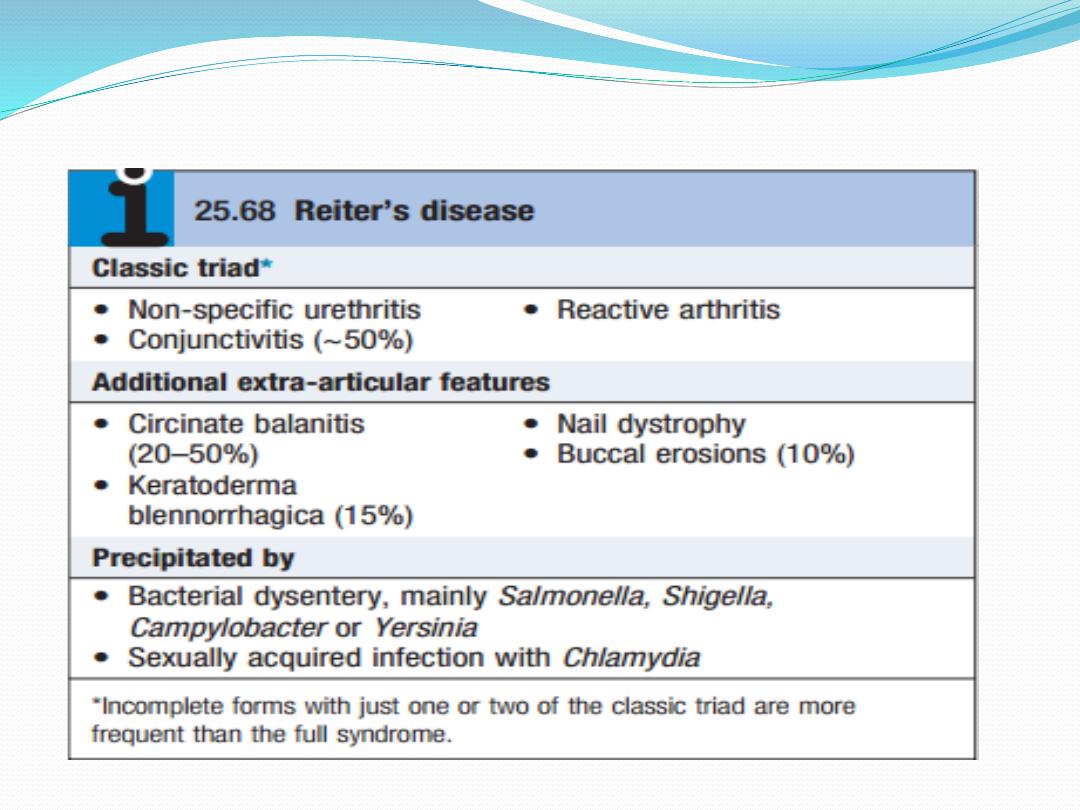

Reactive arthritis

Reactive arthritis (previously known as Reiter’s

disease)

is predominantly a disease of young men, with a male

preponderance of 15 : 1. It is the most common cause

of inflammatory arthritis in men aged 16–35 but may

occur at any age. Between 1 and 2% of patients with

nonspecific urethritis seen at genitourinary medicine

clinics have reactive arthritis . Following an epidemic

of Shigella dysentery, 20% of HLAB27positive

men developed reactive arthritis.

Clinical features

The onset is typically acute, with an inflammatory oligo

arthritis that is asymmetrical and targets lower limb joints,

such as the knees, ankles, midtarsal and MTP joints. It

occasionally presents with single joint involvement and no

clear history of an infectious trigger. There may be

considerable systemic disturbance, with fever and weight

loss. Achilles tendinitis or plantar fasciitis may also be

present. The first attack of arthritis is usually selflimiting,

but recurrent or chronic arthritis develops in more than

60% of patients, and about 10% still have active disease 20

years after the initial presentation. Low back pain and

stiffness are common and 15–20% of patients develop

sacroiliitis. Spondylitis, chronic erosive arthritis, recurrent

acute arthritis and uveitis are the major causes of longterm

morbidity.

Several extraarticular features may occur. Circinate

balanitis starts as vesicles on the coronal margin of the

prepuce and glans penis, later rupturing to form superficial

erosions with minimal surrounding erythema, some

coalescing to give a circular pattern. Lesions are often

painless and may escape notice. Keratoderma

blennorrhagica begins as discrete waxy, yellowbrown

vesicopapules with desquamating margins, occasionally

coalescing to form large crustyplaques. The palms and

soles are particularly affected but spread may occur to the

scrotum, scalp and trunk.

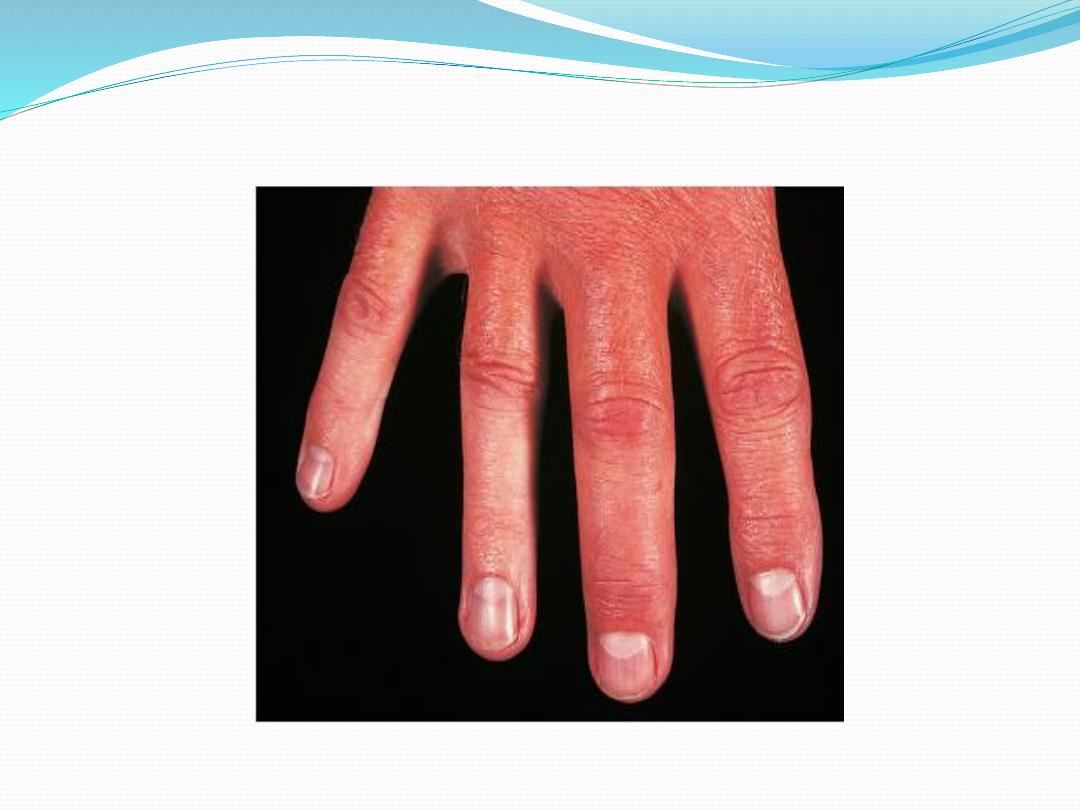

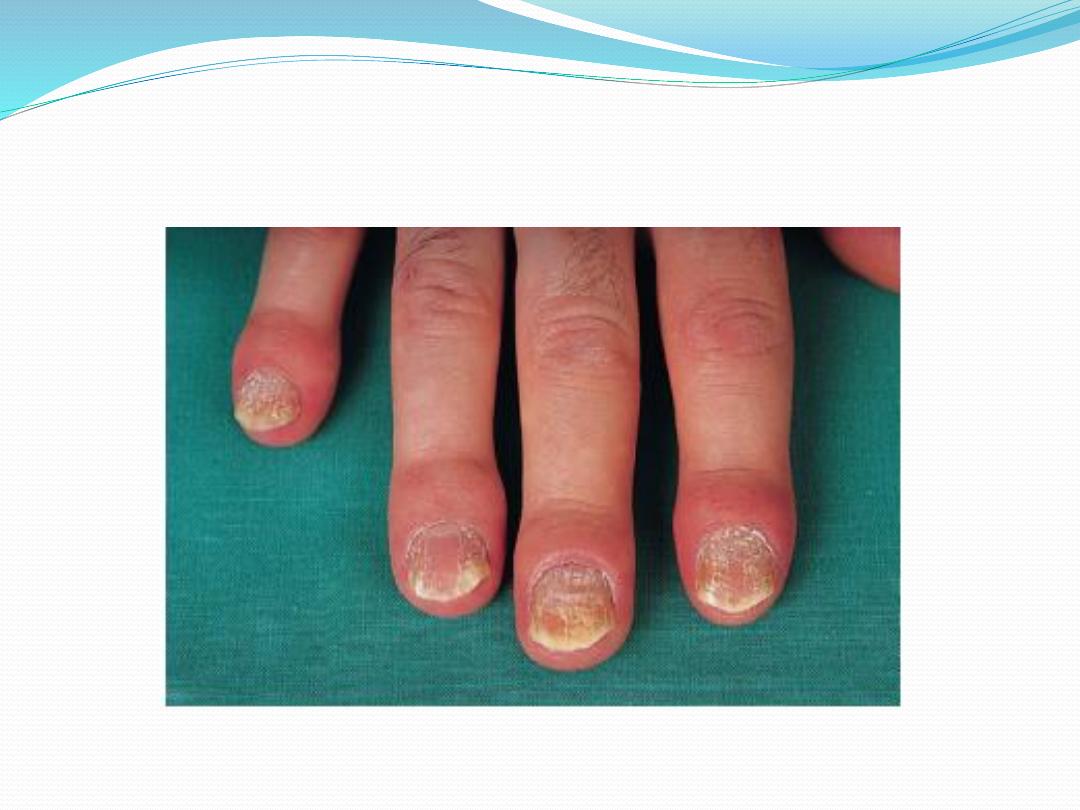

These lesions are indistinguishable from pustular

psoriasis. Nail dystrophy with subungual hyperkeratosis is

common and indistinguishable from psoriatic nail

dystrophy.

Mouth ulcers manifest as shallow red painless

patches on tongue, palate, buccal mucosa and lips,

lasting only a few days. Conjunctivitis may accompany

the first acute episode. Uveitis is rare with the first

attack but occurs in 30% of patients with recurring or

chronic arthritis.

Other complications are rare but include aortic

incompetence, conduction defects, pleuropericarditis,

peripheral neuropathy, seizures and

meningoencephalitis.

Investigations

The diagnosis is usually made clinically but joint aspiration

may be required to exclude crystal arthritis and articular

infection. Synovial fluid is leucocyte rich and may contain

multinucleated macrophages (Reiter’s cells). ESR and CRP

are raised during an acute attack.

Urethritis may be confirmed in the ‘two glass test’ by

demonstration of mucoid threads in the first void

specimen that clear in the second. High vaginal swabs may

reveal Chlamydia on culture. Except for post Salmonella

arthritis, stool cultures are usually negative by the time the

arthritis presents, but serum agglutinin tests may help

confirm previous dysentery. RF, ACPA and ANA are

negative.

In chronic or recurrent disease, Xrays show

periarticular osteoporosis, joint space narrowing and

proliferative erosions. Another characteristic feature is

periostitis, especially of metatarsals, phalanges and

pelvis, and large, ‘fluffy’ calcaneal spurs. In contrast to

AS, radiographic sacroiliitis is often asymmetrical and

sometimes unilateral, and syndesmophytes are

predominantly coarse and asymmetrical, often

extending beyond the contours of the annulus (‘non-

marginal’) . Xray changes in the peripheral joints and

spine are identical to those in psoriasis.

Management

The acute attack should be treated with rest, oral

NSAIDs and analgesics. Intraarticular steroids may be

required in patients with severe synovitis. Nonspecific

chlamydial urethritis is usually treated with a short

course of doxycycline or a single dose of azithromycin,

and this may reduce the frequency of arthritis in

sexually acquired cases. Treatment with DMARDs

should be considered for patients with persistent

marked symptoms, recurrent arthritis or severe

keratoderma blennorrhagica. Anterior uveitis is a

medical emergency requiring topical, subconjunctival

or systemic corticosteroids.

Psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) occurs in 7–20% of patients

with psoriasis and in up to 0.6% of the general

population. The onset is usually between 25 and 40

years of age. Most patients (70%) have preexisting

psoriasis but in 20% the arthritis predates the

occurrence of skin disease. Occasionally, the arthritis

and psoriasis develop synchronously.

Clinical features

The presentation is with pain and swelling affecting

the joints and entheses. Several patterns of joint

involvement are recognised but the course is generally

one of intermittent exacerbation followed by varying

periods of complete or nearcomplete remission.

Destructive arthritis and disability are uncommon,

except in the case of arthritis mutilans.

Asymmetrical inflammatory oligoarthritis

affects

about 40% of patients and often presents abruptly

with a combination of synovitis and adjacent

periarticular inflammation. This occurs most

characteristically in the hands and feet, when synovitis

of a finger or toe is coupled with tenosynovitis,

enthesitis and inflammation of intervening tissue to

give a ‘sausage digit’ or dactylitis . Large joints, such as

the knee and ankle, may also be involved, sometimes

with very large effusions.

Symmetrical polyarthritis

occurs in about 25% of

cases. It predominates in women and may strongly

resemble RA, with symmetrical involvement of small

and large joints in both upper and lower limbs.

Nodules and other extraarticular features of RA are

absent and arthritis is generally less extensive and

more benign. Much of the hand deformity often

results from tenosynovitis and soft tissue contractures.

Distal IPJ arthritisis

an uncommon but characteristic

pattern affecting men more often than women. It

targets finger DIP joints and surrounding periarticular

tissues, almost invariably with accompanying nail

dystrophy

Psoriatic spondylitis

presents a similar clinical picture

to AS but with less severe involvement. It may occur

alone or with any of the other clinical patterns

described above and is typically unilateral or

asymmetric in severity.

Arthritis mutilansis

a deforming erosive arthritis

targeting the fingers and toes that occurs in 5% of

cases of PsA. Prominent cartilage and bone

destruction results in marked instability. The encasing

skin appears invaginated and ‘telescoped’ (‘main en

lorgnette’) and the finger can be pulled back to its

original length.

Nail changes include pitting, onycholysis, subungual

hyperkeratosis and horizontal ridging. They are found

in 85% of those with PsA and only 30% of those with

uncomplicated psoriasis, and can occur in the absence

of skin disease. The characteristic rash of psoriasis

may be widespread, or confined to the scalp, natal

cleft and umbilicus, where it is easily overlooked.

Conjunctivitis can occur, whereas uveitis is mainly con

fined to HLAB27positive individuals with sacroiliitis

and spondylitis.

Investigations

The diagnosis is made on clinical grounds. Autoantibodies

are generally negative and acute phase reactants, such as

ESR and CRP, are raised in only a proportion of patients

with active disease. Xrays may be normal or show erosive

change with joint space narrowing. Features that favour

PsA over RA include the characteristic distribution of

proliferative erosions with marked new bone formation,

absence of periarticular osteoporosis and osteosclerosis.

Imaging of the axial skeleton often reveals features similar

to those in chronic reactive arthritis, with coarse,

asymmetrical, nonmarginal syndesmophytes and

asymmetrical sacroiliitis. MRI and ultrasound with power

Doppler are increasingly employed to detect synovial

inflammation and inflammation at the entheses.

Management

Therapy with NSAID and analgesics may be sufficient

to control symptoms in mild disease. Intraarticular

steroid injections can control synovitis in problem

joints. Splints and prolonged rest should be avoided

because of the tendency to fibrous and bony ankylosis.

Patients with spondylitis should be prescribed the

same exercise and posture regime as in AS.

Therapy with DMARDs should be considered for persistent

synovitis unresponsive to conservative treatment.

Methotrexate is the drug of first choice since it may also

help skin psoriasis, but other DMARDs may also be

effective, including sulfasalazine, ciclosporin and

leflunomide. DMARD monitoring should take place with

particular attention to liver function since abnormalities

are common in PsA. Hydroxychloroquine is generally

avoided, as it can cause exfoliative skin reactions. AntiTNF

treatment should be considered for patients with active

synovitis who respond inadequately to standard DMARDs.

This is effective for both PsA and psoriasis. Other

biological treatments, such as ustekinumab, are emerging,

which target the IL12/23 receptor. Ustekinumab is highly

effective in the treatment of psoriatic skin disease and is

often effective in PsA.

The retinoid acitretin is effective for skin lesions and,

anecdotally, may also help arthritis, but it is

teratogenic so must be avoided in young women. It

also causes mucocutaneous side effects,

hyperlipidaemia, myalgias and extraspinal

calcification. Photochemotherapy with

methoxypsoralen and longwave ultraviolet light

(psoralen +UVA, PUVA) is primarily used for skin

disease, but can also help those with synchronous

exacerbations of inflammatory arthritis.

Enteropathic arthritis

An acute inflammatory oligoarthritis occurs in around

10% of patients with ulcerative colitis and 20% of

those

with Crohn’s disease. It predominantly affects the

large

lower limb joints (knees, ankles, hips) but wrists and

small joints of the hands and feet can also be involved.

The arthritis usually coincides with exacerbations of

the underlying bowel disease, and sometimes is

accompanied by aphthous mouth ulcers, iritis and

erythema nodosum.

It improves with effective treatment of the bowel

disease, and can be cured by total colectomy in

patients with ulcerative colitis. Patients with

inflammatory bowel disease may also develop

sacroiliitis (16%) and AS (6%), which are clinically and

radiologically identical to classic AS. These can

predate or follow the onset of bowel disease and there

is no correlation between activity of the spondylitis

and bowel disease.

The arthritis often remits with treatment of the bowel

disease but DMARD and biological treatment is

occasionally required.

THANK YOU FOR

LISTENING