Conversional disorders

Conversion disorder is characterized by the occurrence of certain signs

or symptoms that are clearly inconsistent with what is known about

anatomy and pathophysiology. The lifetime prevalence of conversion

disorder is not known with certainty, and estimates range from 0.01% to

0.5% of the general population; it is more common in females, with

female to male ratios ranging from 2:1 up to 10:1.

ONSET

Although conversion disorder may appear at any time from early

childhood up to old age, most patients experience their first symptoms

during adolescence or early adult years. In most cases the actual onset

of symptoms is abrupt and typically follows a major stress in the patient's

life.

ETIOLOGY

Conversion symptoms are more common among the uneducated and

unsophisticated; the actual conversion symptom itself is generally a

reflection or extension of symptoms that the patient has seen in another

or has personally experienced.

In most instances, consequent upon the appearance of the:

conversion symptom there is a reduction in the patient s level of

anxiety.

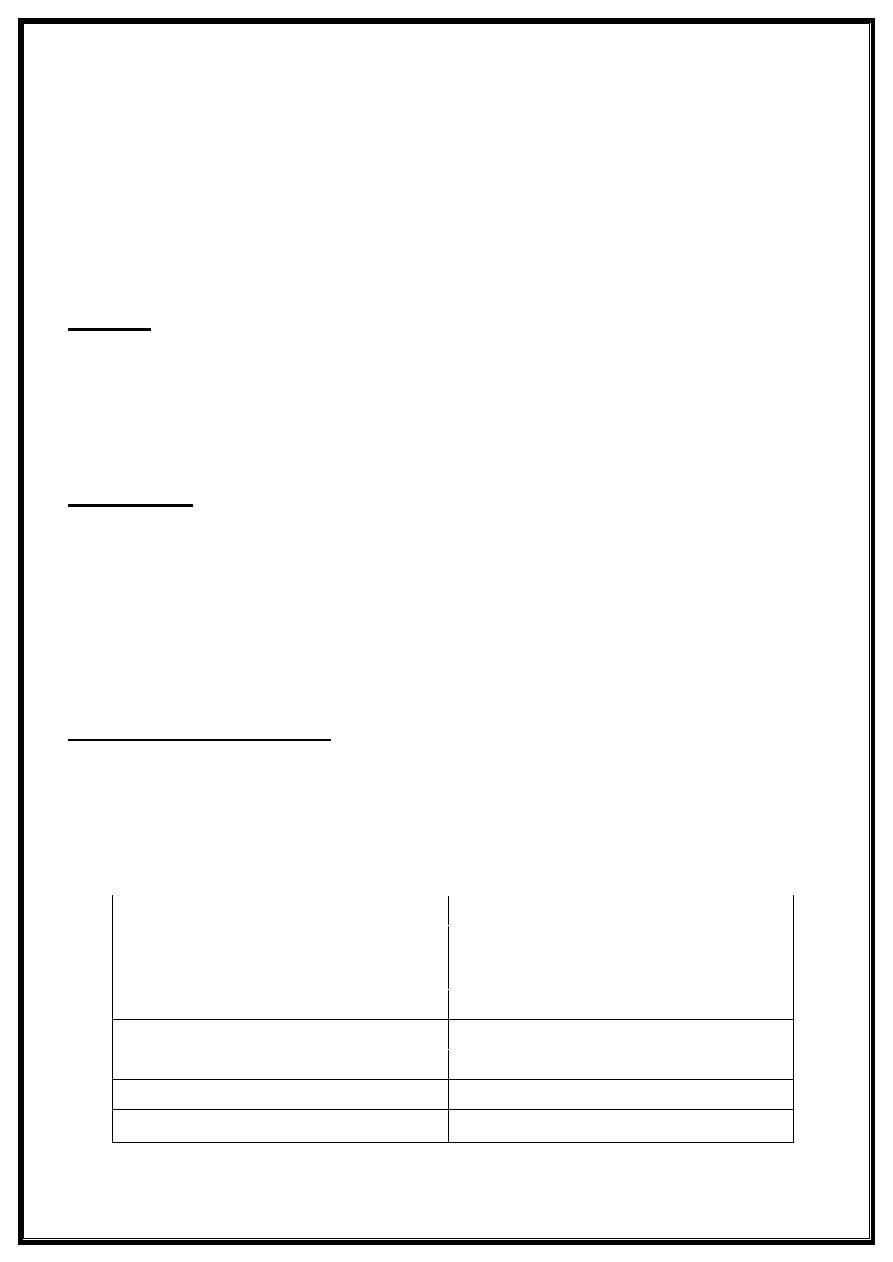

CLINICAL FEATURES

In general, at any given time most patients with conversion disorder have

only one symptom. Some of the more common ones are listed in the box

below, and most of these are described in detail below.

Common Conversion Symptoms

Anesthesia

Parkinsonism

Paralysis

Syncope

Ataxia

Coma

Tremor

Nystagmus

Tonic-clonic Pseudoseizures

Convergencespasm

Deafness

Facial weakness

Blindness

Globus hystericus

Aphonia

Anosmia

Conversion anesthesia

may occur anywhere, but it is most common on the extremities. One

may see a typical "glove and stocking" distribution; however, unlike the

"glove and stocking" distribution that may occur in a polyneuropathy, the

areas of conversion anesthesia have a very precise and sharp

boundary, often located at a joint. The Same non physiologic sharp

boundary may be seen in conversion hemianesthesia, wherein the

boundary precisely bisects the body on a sagittal plane.

In conversion hemiplegia

other abnormalities may be seen; for example, though weak for

many months the affected arm may hang limply at the side, rather

than displaying the typical physiologic flexion posture .Patients with

conversion hemiplegia may also display the "wrong-way tongue"

sign wherein the protruded tongue, instead of deviating toward the

hemiplegic side, as in "true" hemiplegia, deviates instead toward the

normal side. Furthermore, on observation of gait one finds that the

weakened leg is dragged, rather than circumducted. In conversion

paraplegia, one finds normal, rather than increased, deep tendon

reflexes, and the Babinski sign is absent; in doubtful cases the

issue may be resolved by demonstrating normal motor evoked

potentials.

In conversion ataxia

(or, as it has been classically called,astasia- abasia)

a patient, upon attempting to stand or walk, lurches and staggers

forward, arms flinging and trunk swaying, always barely making it to

the safety of bed or chair. Yet when examined in bed, one finds no

limb or truncal ataxia.

Conversion tremor

tends to be coarse and irregular and generally disappears when

the patient is distracted.

Conversion seizures

also known as "hysterical fits" or "non-epileptic seizures/' may

mimic either grand mal or complex partial seizures.

In conversion deafness

the blink reflex to a loud and unexpected sound is present, thus

demonstrating the intactness of the brain stem. Should one suspect

the vanishingly rare bilateral cortical deafness, a brain stem auditory

evoked potential will resolve the issue.

Bilateral conversion blindness

may be suspected when the patient, though complaining of recent

onset of blindness, neither sustains. injury while maneuvering

around the officenor displays any of the expected bruises or

scrapes. The pupillary reflex is present, avisual evoked potential will

resolve the question.

In cases of monocular conversion blindness

one need only demonstrate two things to make the correct

diagnosis: first ,that the peripheral fields are full in the unaffected

eye; and second, that the pupillary response is normal in both eyes.

Conversion aphonia

may be suspected when the patient is asked to cough, for example,

during auscultation of the lungs. ln contrast with other aphonias, the

cough is normally full and loud. A synonym for"globus hystericus"

might be conversion dysphagia; however, this term fails to convey

the essence of the patient's chief complaint, which is a most

distressing sense of having a lump in one's throat. Finding that the

patient can swallow solid food with little difficulty or even that

swallowing liquid may ease the discomfort argues strongly for a

diagnosis of globus.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is determined after ruling out organic components or other

psychogenic diagnosis. This may involve brain scans such as MRI or CT

scanning as well as blood tests. Electrophysiological studies

(electroencephalography, sensory and motor evoked potentials,

urodynamics) are usually normal. There are no pathological findings in

laboratory tests, supporting CD. On the other hand, however,

pathological findings will not necessarily rule out CD3. Conversion

reactions need to be distinguished from malingering. With malingering,

the patient has a conscious secondary gain in mind.

Treatment

1-Aggressive therapy of comorbid psychiatric illness.

2-Pharmacotherapy Anxiolytic or antidepressant medications.

3-Psychotherapy.

Dr.Hassan M. Al jumaily

Neurologist