1

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Vesicoureteric reflux (VUR)

VUR is the abnormal retrograde flow of urine from the bladder into the upper urinary

tract with or without dilatation of the ureter, renal pelvis, and calyces. It can cause symptoms

and may lead to renal failure (reflux nephropathy).

Epidemiology

Overall incidence in children is >10%; younger > older; girls > boys (female: male

ratio 5:1); Caucasian > African. Siblings of an affected child have a 40% risk of reflux, and

routine screening of siblings is recommended.

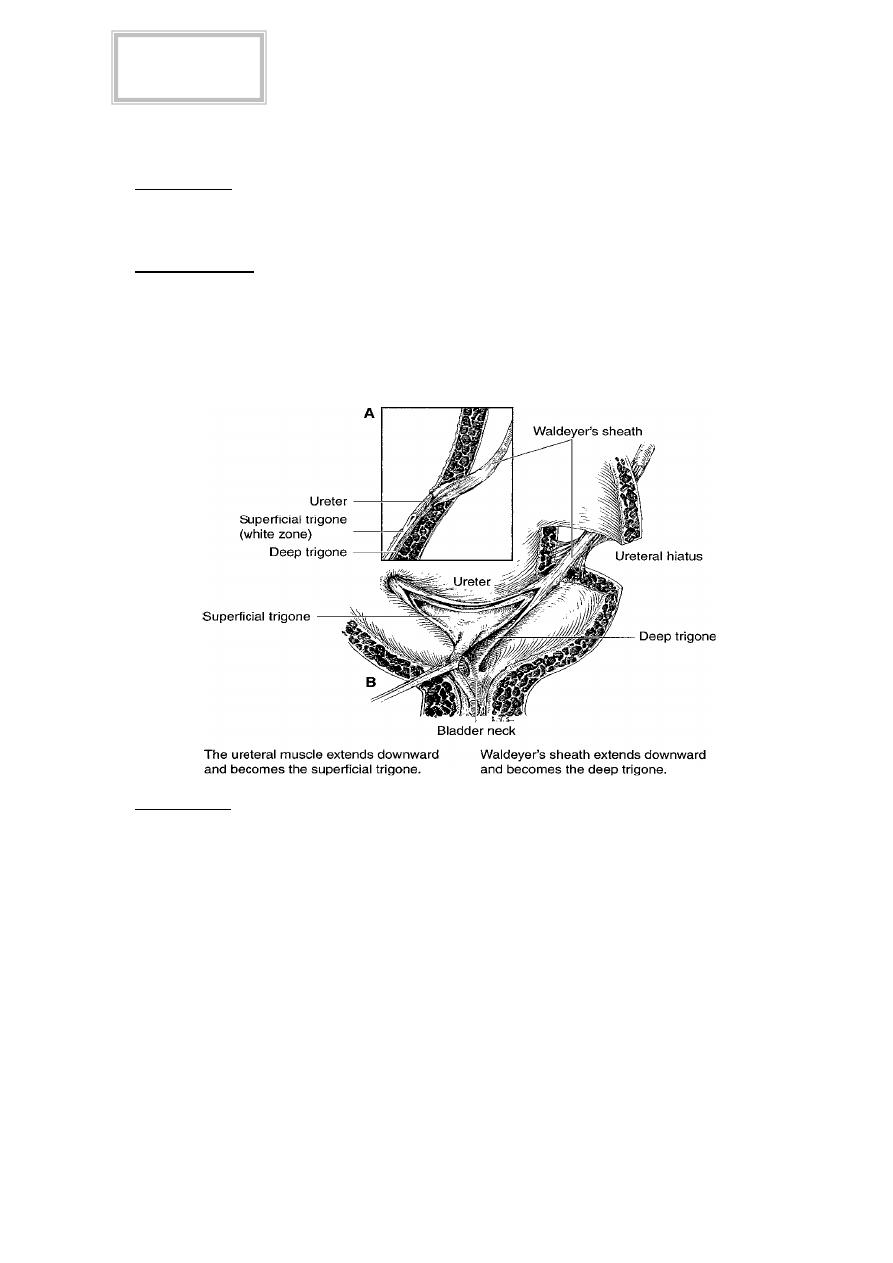

Pathophysiology

Reflux is normally prevented by low bladder pressures, efficient ureteric peristalsis,

and the ability of the vesicoureteric junction (VUJ) to occlude the distal ureter during bladder

contraction. This is assisted by the ureters passing obliquely through the bladder wall

(the intramural ureter), which is about 1.5cm long. Normal intramural ureteric length to ureteric

diameter ratio is 5:1. VUR of childhood tends to resolve spontaneously with increasing age

because as the bladder grows, the intramural ureter lengthens.

Classification

Primary: a primary anatomical (and therefore functional) defect where the intramural length of

the ureter is too short (ratio <5:1).

Secondary to some other anatomical or functional problem:

Bladder outlet obstruction (BPH, posterior urethral valves, urethral stricture) which

leads to elevated bladder pressures.

Poor bladder compliance or the intermittently elevated pressures of detrusor

hyperreflexia (due to neuropathic disorders e.g. spinal cord injury, spina bifida).

Iatrogenic reflux following TURP or TURBT (a tumor overlying the ureteric orifice);

ureteric meatotomy (incision of the ureteric orifice) for removal of ureteric stones at the

VUJ; following incision of a ureterocele; ureteroneocystostomy; post pelvic

radiotherapy.

Inflammatory conditions affecting function of the VUJ: TB, schistosomiasis, UTI.

Tikrit Medical College

Urology

Fifth year

2

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Associated disorders

VUR is commonly seen in duplex ureters (the Meyer Weigert law). Cystitis can cause

VUR through bladder inflammation, reduced bladder compliance, increased pressures, and

distortion of the VUJ. Coexistence of UTI with VUR is a potent cause of pyelonephritis & reflux

of infected urine under high pressure causes reflux nephropathy, resulting in renal scarring,

hypertension, and renal impairment.

Presentation

VUR may be symptomless, being identified during VCUG, IVU, or renal ultrasound

(which shows ureteric and renal pelvis dilatation) done for some other cause.

UTI symptoms.

Loin pain associated with a full bladder or immediately after micturition.

Symptoms of recurrent UTI or of loin pain may have been present for many years before the

patient seeks medical advice.

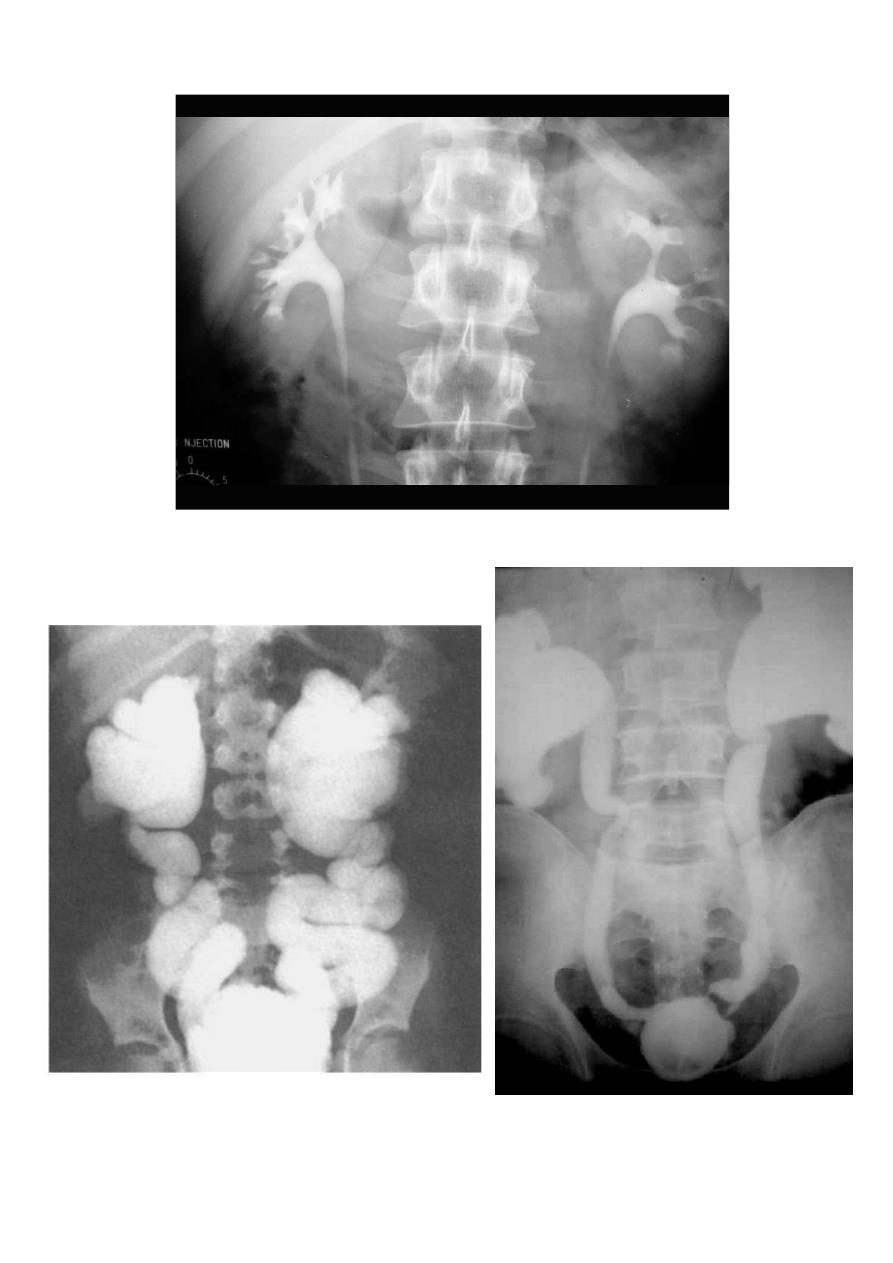

Investigation

The definitive test for the diagnosis of VUR is cystography. VUR may be apparent during

bladder filling or during voiding (voiding cystourethrography VCUG also known as micturating

cystourethrography, MCUG). Urodynamics establishes the presence of voiding dysfunction if

this is suspected from the clinical picture. If there is radiographic evidence of reflux

nephropathy check blood pressure, check the urine for proteinuria, measure serum creatinine,

and arrange a

99m

Tc-DMSA isotope study to assess renal cortical scarring.

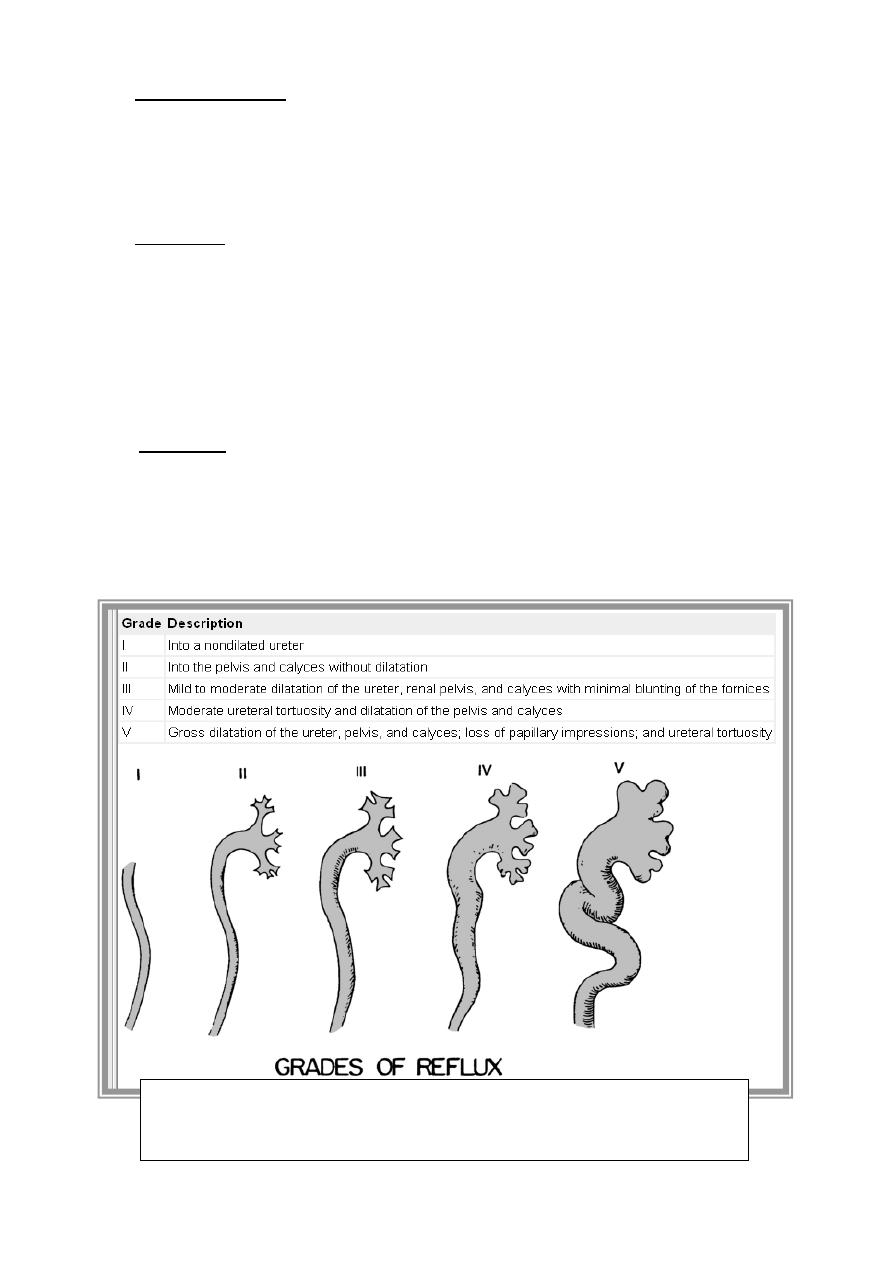

Grading System

The international grading system for reflux is based primarily on the radiographic

appearance of the calyces on voiding cystourethrography (VCUG).

3

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

NORMAL

VUR

VUR

4

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Management

The management of patients is based on the observation that VUR has a natural

tendency for Spontaneous resolution. Surgical correction can often be avoided by maintaining

the patient on careful medical surveillance and continuous antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent

secondary renal damage. The decision for medical versus surgical management is made after

a careful diagnostic evaluation, with particular focus on the grade of reflux and age of the

patient. Most grade I to III refluxes resolve spontaneously, as do some in grade IV. Grade V

refluxes seldom resolve on their own. Reflux is more likely to resolve spontaneously in younger

children regardless of grade.

Medical

Medical management consists of continuous low-dose antibiotic prophylaxis, regular

urine cultures (every 3 months), and a yearly cystogram and renal ultrasound. Medical

surveillance is appropriate for young children with mild-to-moderate grades of reflux (I & III)

and very young children with grade IV reflux. Ampicillin or amoxicillin is appropriate for children

younger than 6 weeks, whereas trimethoprim & sulfamethoxazole can be used after 6 weeks

(mature biliary system). Grade V reflux also is managed medically in newborns until the child is

old enough for surgical management.

Secondary reflux:

treat the underlying cause & relieve BOO, improve bladder compliance.

Surgical

The success rate for antireflux procedures is greater than 95% in experienced hands.

Indications for early surgical intervention follow.

Breakthrough infection despite antibiotic prophylaxis

Poor compliance with medical regimen

Progressive renal scarring with antibiotic prophylaxis

A refluxing orifice within a diverticulum

Severe reflux (grade IV or V)

VUR that persists after puberty

VUR associated with congenital anomalies like double ureter

Techniques include laparoscopic repair and open ureteric re-implantation:

Intravesical methods involve mobilizing the ureter and advancing it across the trigone

(Cohen repair) or reinsertion into a higher, medial position in the bladder

(Politano & Leadbetter repair).

Extravesical techniques involve attaching the ureter into the bladder base and suturing

muscle around it (Lich & Gregoir procedure).

Alternatively, endoscopic subtrigonal injections into the ureteric orifice has 70%

success, rising to 95% with repeated treatments.

Reflux into a non-functioning kidney (<10% function on DMSA scan) with recurrent

UTIs and/or hypertension: nephroureterectomy.

5

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Renal Transplantation

The 50th anniversary of the first successful kidney transplant from a live donor to his

identical twin was celebrated in 2004. During this interval, kidney transplantation has

progressed from an experimental procedure to the preferred method of renal replacement

therapy worldwide. The first long-term success with human renal allografting, in which the

patient survived for over a year, occurred in Boston in 1954, when a kidney from one twin was

transplanted into the other, who had ESRD. Thirty-six years after the first long-term success of

human-to-human kidney transplantation, Joseph E. Murray received the Nobel Prize in

Medicine in 1990 for his pioneering work in renal transplantation.

Renal transplantation is clearly the preferred treatment for patients with permanent

renal failure (GFR, <10 mL/minute, or serum creatinine, >8 mg/dL). It provides significantly

longer survival over dialysis and a better quality of life. Because of the increasing numbers of

patients requiring transplantation and the long waits for cadaveric kidneys, living related-donor

renal transplantation is increasing. Living related donors have a better probability of graft

survival and can allow patients to have preemptive renal transplantation before ever needing to

go on dialysis.

Recipient Selection

Contraindications to Transplantation

Active infection

Recent malignant disease

Active glomerulonephritis

Presensitization to donor class I human leukocyte antigen (HLA) antigens

Donor Selection

Living Related Donors

Living related and unrelated donors are an increasing source of kidney transplants in

the because of superior graft survival and a shortage of cadaveric kidneys. Donors are

expected to be in perfect physical and mental health with negative blood and tissue

cross-matches. Compatibility by mixed lymphocyte culture is demonstrated by negative HLA

antigenic stimulation.

Cadaver Donors

Cadaver donors are generally persons between ages 2 and 60 years without evidence

of significant hypertension, atherosclerosis, renal disease, malignancy, or infection. Blood and

urine cultures should be negative, with creatinine less than 2 mg/dL, and hepatitis B antigen

(HBsAg) negative. The heart must be pumping, and no longer than 10 minutes of warm

ischemia should exist. After removal, kidneys are flushed with ice-cold Collins' solution and

stored in ice slush (for 24-48 hours) or preserved by pulsatile perfusion (for 48-72 hours).

Tissue Matching

The HLA gene products (cell-surface antigens) from each haplotype are classified as

class I serologically defined HLA-A, -B, and -C and the class II HLA-DR (D-related) antigens.

Matching for major HLA antigens among closely related living donors has been shown to

predict results superior to those with cadaveric donors because of compatibility among other

less important gene products of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region. Living

related transplants between HLA identical siblings (two-haplotype match) yield the highest

1-year graft survival (up to 90%), followed next by HLA semi-identical (one-haplotype match).

The ABO (H) blood group antigens are expressed on vascular endothelium and

therefore must be matched for renal transplantation. However, Rh antigens are not expressed

on nucleated cells and need not be of concern.

6

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Immunosuppression

The allograft response is directed primarily against mismatched HI.A antigens and is

T cell dependent. Immunosuppression is important to prevent rejection.

Perioperative Considerations

The usual preoperative laboratory tests, including a urine culture, chest radiograph,

and electrocardiogram (ECG), should be obtained. Most patients will require preoperative

dialysis. Immunosuppressive medications should be started preoperatively as dictated by the

prescribed protocol. Prophylactic antibiotics should be given on call to the operating room. A

living related donor should be kept well hydrated with optimal urine output.

Complications

Acute Tubular Necrosis

ATN is the most common cause of early oliguria or anuria after transplantation and is

the result of ischemic insult to the kidney. Recovery will generally occur within 3 to 6 weeks;

however, a renal biopsy may be helpful to rule out rejection. The diagnosis is made primarily by

exclusion.

7

أ.د. حممد حمسن عبد العزيز

Rejection

Hyperacute or Accelerated Rejection.

Hyperacute rejection is generally an irreversible process that begins within minutes to hours

after transplantation and is the result of presensitization of the recipient with cytotoxic

antibodies to donor ABO.

Acute Rejection

Acute rejection occurs within 3 months after transplantation and is clinically

characterized by fever, swelling, and tenderness over the graft, with decreased function and

urine output. Hypertension also may be present.

Chronic Rejection

Chronic rejection results in a gradual deterioration of function, months to years after

transplantation, without clear evidence of a rejection episode.

Surgical Complications

Vascular Complications

Vascular complications occur infrequently after transplantation; however, when they

occur, they can be disastrous and must be recognized immediately.

Thrombophlebitis

Thrombophlebitis is a relatively uncommon occurrence; however, if it is suspected,

ultrasound or phlebography should be performed.

Graft Rupture

Graft rupture usually occurs as spontaneous severe pain and shock from massive life-

threatening hemorrhage. It is believed to be caused by acute rejection and ischemia.

Immediate nephrectomy is indicated.

Lymphatic

Lymphatic drainage from the area of dissection may occasionally be excessive,

resulting in leakage from the incision or surgical drains. Occasionally, more prolonged drainage

can result in a lymphocele, which is best diagnosed with ultrasound.

Infectious Complications

Infections are the most common and life-threatening complications for the transplant

recipient. Immunosuppressive therapy coupled with leukopenia, hyperglycemia, and azotemia

markedly increases the risk of serious complicated infections. Bacterial sepsis is most

common; however, opportunistic infections such as those with cytomegalovirus (CMV),

Pneumocystis carinii, or Candida albicans are major problems.

Urinary Tract Infections

Urinary tract infections are a common source of bacterial sepsis in the post transplant

patient. Use of prophylactic antibiotics and early removal of the Foley catheter can help lessen

their incidence.

Wound Infection

Wound infection must always be suspected in the posttransplant patient with high

fever. The incision will often look benign, even in the face of a grossly purulent abscess. Do not

underestimate the masking effect of immunosuppressive agents.

Pulmonary Infection

Pulmonary infection with gram-negative bacteria, fungi, P. carinii, and CMV usually

appears with fever and pulmonary infiltrates. However, CMV and Pneumocystis can often

cause severe respiratory failure before radiographic evidence of pneumonia.

Meningitis

Meningitis will often be masked by immunosuppressive therapy. Patients with

unexplained fever, dull headache, photophobia, or mental-status changes should undergo

lumbar puncture. Look for Listeria, Candida, Cryptococcus, and Aspergillus.