Pathology of the small & large intestine

Ass. Professor Haider Abd Ul RidhaM.B.ch.B. F.I.C.M.S. path.

Learning objective

Pathological process related to:• Intestinal obstruction

• Ischemic bowel disease

• Malabsorption – infectious diseases

• Congenital diseases.

Intestinal obstruction

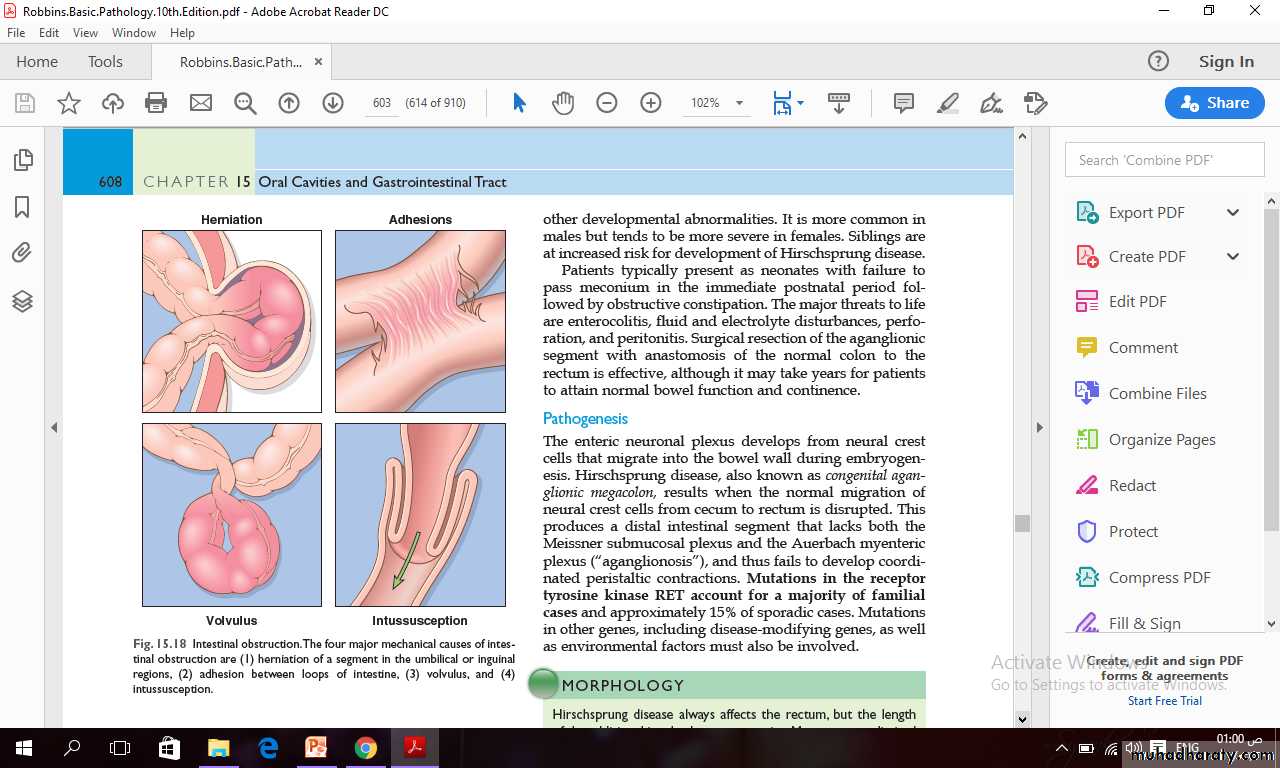

Obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract may occur at any level, but the small intestine is most often involved because of its relatively narrow lumen.Collectively, hernias, intestinal adhesions, intussusception, and volvulus account for 80% of mechanical obstructions while tumors and infarction account for most of the remainder.

Abdominal Hernia

Any weakness or defect in the wall of the peritoneal cavity may permit protrusion of a serosa-lined pouch of peritoneum called a hernia sac.Acquired hernias most commonly occur anteriorly, through the inguinal and femoral canals or umbilicus, or at sites of surgical scars. These are of concern because of visceral protrusion (external herniation).

Inguinal hernias, tend to have narrow orifices and large sacs.

Small bowel loops are herniated most often, but portions of omentum or large bowel also protrude, and any of these may become entrapped.Pressure at the neck of the pouch may impair venous drainage, leading to stasis and edema.

These changes increase the bulk of the herniated loop, leading to permanent entrapment and over time, arterial and venous compromise, or strangulation, can result in infarction.

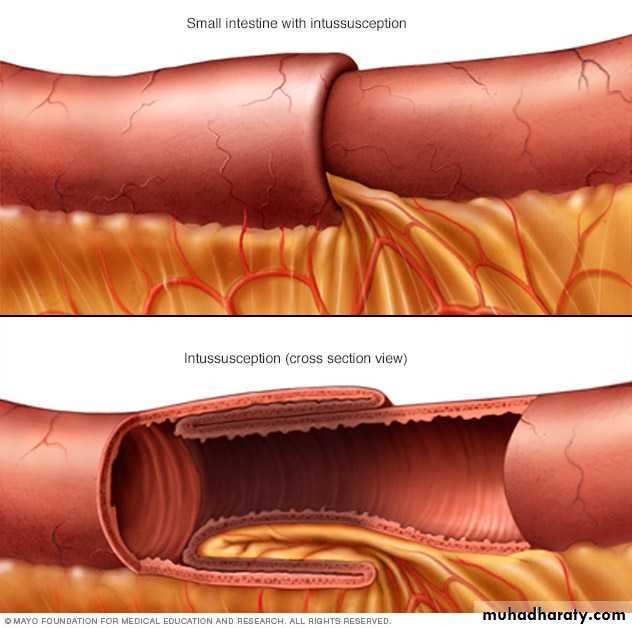

Intussusception

It occurs when a segment of the intestine, constricted by a wave of peristalsis, telescopes into the immediately distal segment.Once trapped, the invaginated segment is propelled by peristalsis and pulls the mesentery along.

Untreated intussusception may progress to intestinal obstruction, compression of mesenteric vessels, and infarction.

Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in children younger than 2 years of age.

Etiology of Intussusception

There usually is no underlying anatomic defect and the child is otherwise healthy.Some cases are associated with viral infection and rotavirus vaccines and may be related to reactive hyperplasia of Peyer patches, which can act as the leading edge of the intussusception.

Gross features of Intussusception

Hirschsprung disease (congenital aganglionic megacolon)

It is due to congenital defect in colonic innervation.

It may be isolated or occur in combination with other developmental abnormalities. It is more common in males but tends to be more severe in females. Siblings are at increased risk for development of Hirschsprung disease.

Clinical presentation

Patients present as neonates with failure to pass meconium in the immediate postnatal period followed by obstructive constipation.The major threats to life are enterocolitis, fluid and electrolyte disturbances, perforation, and peritonitis.

Surgical resection of the aganglionic segment with anastomosis of the normal colon to the rectum is effective, although it may take years for patients to attain normal bowel function and continence.

Pathogenesis

The enteric neuronal plexus develops from neural crest cells that migrate into the bowel wall during embryogenesis.when the normal migration of neural crest cells from cecum to rectum is disrupted.

This produces a distal intestinal segment that lacks both the Meissner submucosal plexus and the Auerbach myenteric plexus (“aganglionosis”), and thus fails to develop coordinated peristaltic contractions.

Hirschsprung disease always affects the rectum, but the length of the additional involved segments varies.

Most cases are limited to the rectum and sigmoid colon, but severe disease can involve the entire colon.

The aganglionic region may have a grossly normal or contracted appearance, while the normally innervated proximal colon may undergo progressive dilation as a result of functional distal obstruction.

Diagnosis is made by demonstrating the absence of ganglion cells in the affected segment.

Vascular disorders of bowel

The greater portion of the gastrointestinal tract is supplied by the celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric arteries.As they approach the intestinal wall, the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries fan out to form the mesenteric arcades.

Interconnections between arcades, as well as collateral supplies from the proximal celiac and distal pudendal and iliac circulations, make it possible for the small intestine and colon to tolerate slowly progressive loss of the blood supply from one artery.

By contrast, acute compromise of any major vessel can lead to infarction of several meters of intestine.

Ischemic bowel disease

Ischemic damage to the bowel wall can range from mucosal infarction, extending no deeper than the muscularis mucosa; to mural infarction of mucosa and submucosa; to transmural infarction involving all three layers of the wall.

Mucosal or mural infarctions often are secondary to acute or chronic hypoperfusion, transmural infarction is generally caused by acute vascular obstruction.

Causes of acute arterial obstruction

Severe atherosclerosis (which is often prominent at the origin of mesenteric vessels), aortic aneurysm.Hypercoagulable states, oral contraceptive use.

Embolization of cardiac vegetations or aortic atheromas.

Causes of intestinal hypoperfusion

Cardiac failure.

Shock.

Dehydration.

Vasoconstrictive drugs.

Damage intestinal arteries

Systemic vasculitides, such as polyarteritis nodosum, Henoch-Shonlein purpura, or Wegener granulomatosis.

PATHOGENESIS

Intestinal responses to ischemia occur in two phases.The initial hypoxic injury occurs at the onset of vascular compromise and, although some damage occurs, intestinal epithelial cells are relatively resistant to transient hypoxia.

The second phase, reperfusion injury, is initiated by restoration of the blood supply and associated with the greatest damage.

In severe cases multiorgan failure may occur. While the underlying mechanisms of reperfusion injury are incompletely understood, they involve free radical production, neutrophil infiltration, and release of inflammatory mediators, such as complement proteins and cytokines.

Factors that determine severity of ischemic bowel disease

• The severity of vascular compromise.

• Time during which vascular compromise develops.

• Vessels affected.

Gross features

Involvement is frequently segmental and patchy, and the mucosa is hemorrhagic and often ulcerated.The bowel wall is thickened by edema that may involve the mucosa or extend into the submucosa and muscularis propria.

With severe disease, pathologic changes include extensive mucosal and submucosal hemorrhage and necrosis, but serosal hemorrhage and serositis generally are absent.

Damage is more pronounced in acute arterial thrombosis and transmural infarction.

Blood tinged mucus or blood accumulates within the lumen.

Coagulative necrosis of the muscularis propria occurs within 1 to 4 days and may be associated with purulent serositis and perforation.

Microscopical features

Atrophy or sloughing of surface epithelium.Crypts may be hyperproliferative.

Inflammatory infiltrates are initially absent in acute ischemia, but neutrophils are recruited within hours of reperfusion.

Chronic ischemia is accompanied by fibrous scarring of the lamina propria and stricture formation.

In acute phases of ischemic damage, bacterial superinfection and enterotoxin release may induce pseudomembrane formation that can resemble Clostridium difficile–associated pseudomembranous colitis

Intestinal Ischemia.

(A)Characteristic attenuated and partially detached villous epithelium in acute jejunal ischemia.

(B)Chronic colonic ischemia with atrophic surface epithelium and fibrotic lamina propria

A

B

Malabsorption results from disturbance in at least one of the four phases of nutrient absorption:

• Intraluminal digestion, in which proteins, carbohydrates, and fats are broken down into absorbable forms.

• Terminal digestion, which involves the hydrolysis of carbohydrates and peptides by disaccharidases and peptidases, respectively, in the brush border of the small-intestinal mucosa.

• Transepithelial transport, in which nutrients, fluid, and electrolytes are transported across and processed within the small-intestinal epithelium.

• Lymphatic transport of absorbed lipids.

Celiac disease

Its an immune-mediated enteropathy triggered by the ingestion of gluten-containing cereals, such as wheat, rye, or barley, in genetically predisposed individuals. The primary treatment for celiac disease is a gluten-free diet, which results in symptomatic improvement for most patients.Pathogenesis of celiac disease

Celiac disease is an intestinal immune reaction to gluten, the major storage protein of wheat and similar grains.Gluten is digested by luminal and brush border enzymes into amino acids and peptides, including a 33–amino acid gliadin peptide that is resistant to degradation by gastric, pancreatic, and small-intestinal proteases.

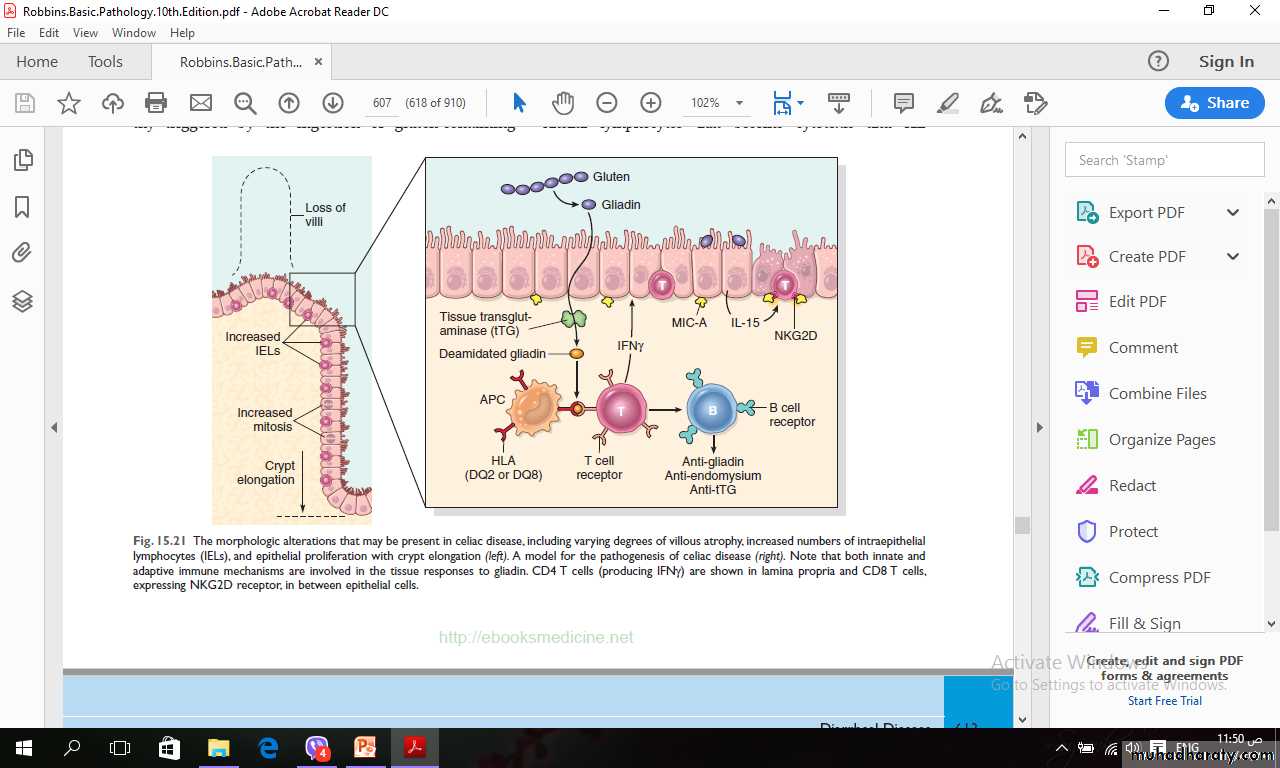

Gliadin is deamidated by tissue transglutaminase and is then able to interact with HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 on antigen-presenting cells and be presented to CD4+ T cells.

These T cells in lamina propria produce cytokines that likely contribute to the tissue damage and characteristic mucosal histopathology.

An antibody response follows: This includes production of antibodies against tissue transglutaminase, deamidated gliadin, and, perhaps as a result of cross-reactive epitopes, anti-endomysial antibodies, which can be diagnostically useful.

Pathogenesis of celiac disease (cont.)

It is thought that deamidated gliadin peptides induce epithelial cells to produce the cytokine IL-15, which in turn triggers activation and proliferation of CD8+ intraepithelial lymphocytes that become cytotoxic and kill enterocytes that have been induced by various stressors to express surface MIC-A.

This molecule is recognized by the NKG2D receptor on activated CD8+ T cells.

The damage caused by these immune mechanisms may increase the movement of gliadin peptides across the epithelium, which are then deamidated by tissue transglutaminase, thus perpetuating the cycle of disease.

The morphologic alterations that may be present in celiac disease, including varying degrees of villous atrophy, increased numbers of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), and epithelial proliferation with crypt elongation (left).

A model for the pathogenesis of celiac disease (right). Note that both innate and

adaptive immune mechanisms are involved in the tissue responses to gliadin. CD4 T cells (producing IFNγ) are shown in lamina propria and CD8 T cells, expressing NKG2D receptor, in between epithelial cells.

Celiac disease.

(A) Advanced cases of celiac disease show complete loss of villi, or total villous atrophy. Note the dense plasma cell infiltrates in the lamina propria.(B) Infiltration of the surface epithelium by T lymphocytes, which can be recognized by their densely stained nuclei (labeled T). Compare with elongated, pale-staining epithelial nuclei (labeled E).

A

B

T

E

Microscopical features

There is characteristic increased numbers of T lymphocytes, with intraepithelial lymphocytosis, crypt hyperplasia, and villous atrophy.increased numbers of plasma cells, mast cells, and eosinophils, especially within the upper part of the lamina propria. It should be noted that intraepithelial lymphocytosis and villous atrophy can be present in other disorders, including viral enteritis.

The combination of histologic and serologic findings is, therefore, most specific for diagnosis of celiac disease.