.

CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES OF THE SPLEEN

Splenic agenesis is rare, but is present in 10 per cent of children with congenital

heart disease. Polysplenia is a rare condition resulting from failure of splenic

fusion.

Splenunculi are single or multiple accessory spleens that are found in

approximately 10–30 per cent of the population.They are located near the hilum

of the spleen in 50 per cent of cases and are related to the splenic vessels or

behind the tail of the pancreas in 30 per cent. The remainder are located in the

mesocolon or the splenic ligaments. Their significance lies in the fact that failure

to identify and remove these at the time of splenectomy may give rise to

persistent disease.

Hamartomas are rarely found in life and vary in size from 1 cm in diameter to

masses large enough to produce an abdominal swelling.

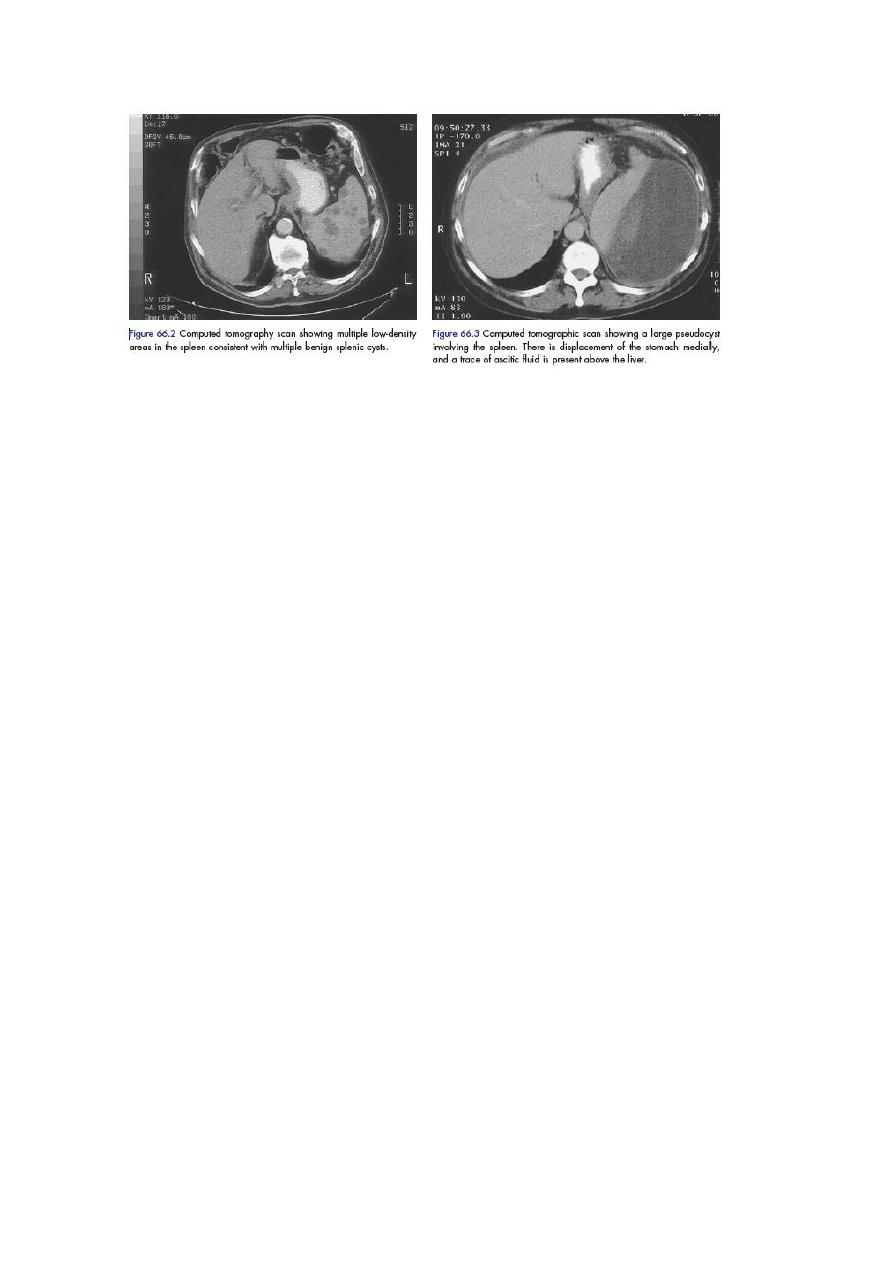

Non-parasitic splenic cysts are rare. Splenic cysts are classified as primary cysts

(true) or pseudocysts (secondary) on the basis of the presence or absence of

lining epithelium. True cysts form from embryonal rests and include dermoid

and mesenchymal inclusion cysts. True cysts of the spleen are very rare and are

frequently classified as cystic hemangiomas, and epidermoid and dermoid cysts.

Epidermoid cysts are thought to be of congenital origin and represent 10 per

cent of the splenic cysts. They are lined by flattened squamous epithelium and

are more frequent in children and young patients. Splenectomy or partial

splenectomy is usually considered for cysts larger than 5 cm in diameter. These

should be differentiated from false or secondary cysts that may result from

trauma and contain serous or haemorrhagic fluid. The walls of such degenerative

cysts may be calcified and therefore resemble the radiological appearances of a

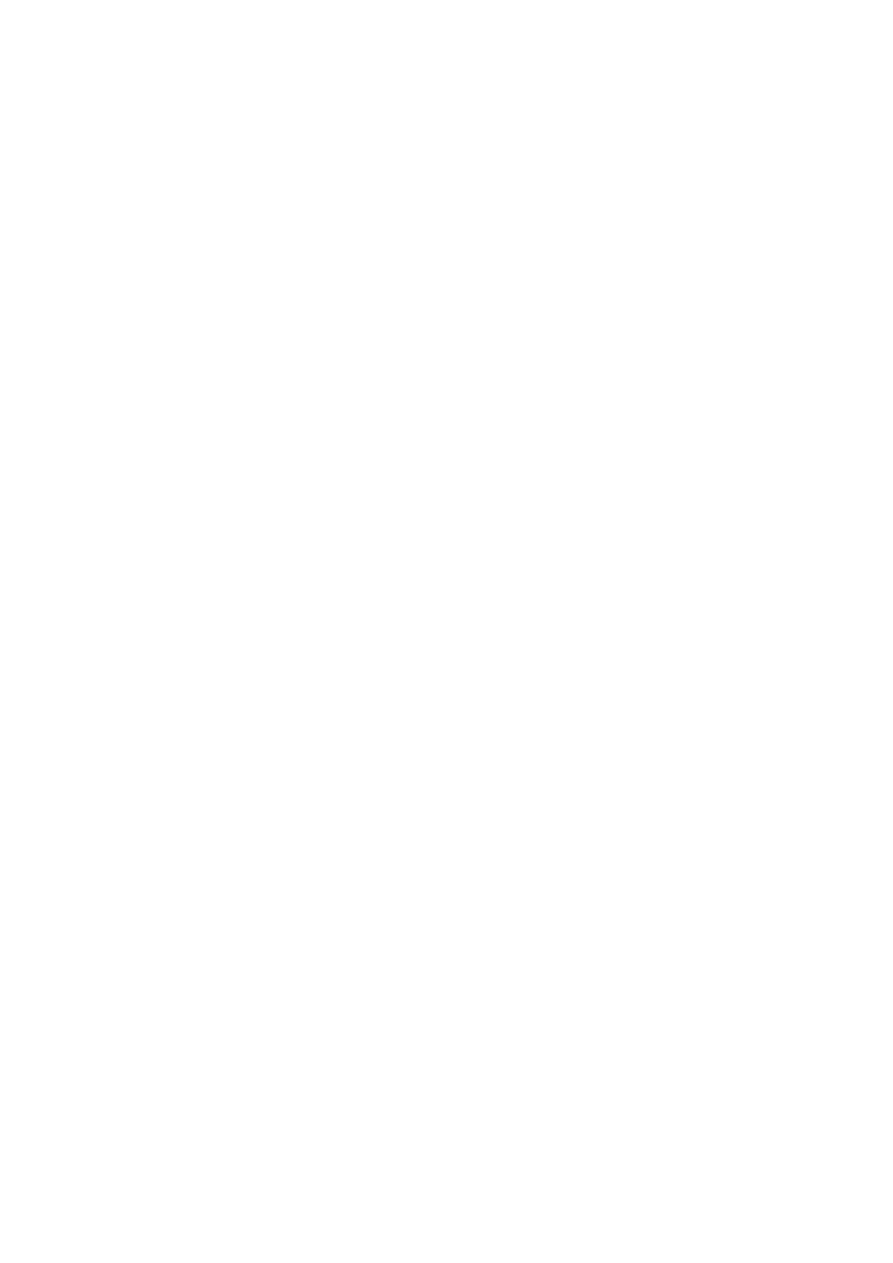

hydatid cyst. The spleen is also a common site for pseudocyst development

following a severe attack of pancreatitis). Pseudocysts can easily be diagnosed

on scanning, and intervention is normally required for symptomatic lesions that

persist following a period of observation

.

SPLENIC ARTERY ANEURYSM, INFARCT AND RUPTURE

Splenic artery aneurysm

They are twice as common in the female and are usually situated in the main

arterial trunk. Although these are generally single, more than one aneurysm is

found in a quarter of cases. These may be a

consequence of intra-abdominal sepsis and pancreatic necrosis in particular.

They are more likely to be associated with arteriosclerosis in elderly patients.

The aneurysm is symptomless unless it

Almost half the cases of rupture occur in patients younger than 45 years of age,

and a quarter are in pregnant women, usually in the third trimester of pregnancy

or

at labour. Aneurysmal rupture carries a high mortality rate and

The treatment ligation of the proximal and distal ends of the sac to allow

thrombosis

of the aneurysm and partial or complete splenectomy if necessary.. Embolisation

or endovascular stenting following selective splenic artery angiography can be

considered

Splenic infarction

This condition commonly occurs in patients with a massively enlarged spleen

from myeloproliferative syndrome, portal hypertension or vascular occlusion

produced by pancreatic disease, splenic vein thrombosis or sickle cell disease.

The infarct may be asymptomatic or give rise to left upper quadrant and left

shoulder tip pain. A contrast-enhanced CT will show the characteristic perfusion

defect in the enlarged spleen ,

Treatment is conservative and splenectomy should be considered only when a

septic infarct causes an abscess.

Splenic rupture

Splenic rupture should be considered in any case of blunt abdominal trauma,

particularly when the injury occurs to the left upper quadrant of the abdomen.

Iatrogenic injury to the spleen remains a frequent complication of any surgical

procedure, particularly those in the left upper quadrant when adhesions are

present. Splenic injury occurs from direct blunt trauma. Most isolated splenic

injuries, especially in children, can be managed nonoperatively. However, in

adults, especially in the presence of other injury, age >55 years, or physiological

instability, splenectomy should be considered.

.

SPLENOMEGALY AND HYPERSPLENISM

Splenomegaly Few conditions that cause splenomegaly will require

splenectomy as part of treatment.

Hypersplenism is an indefinite clinical syndrome that is characterised by

splenic enlargement, any combination of anaemia, leucopenia or

thrombocytopenia, compensatory bone marrow hyperplasia and improvement

after splenectomy. Careful clinical judgement is required to balance the long-

and short-term risks of splenectomy against continued conservative

management.

Splenic abscess

Splenic abscess may arise from an infected splenic embolus or in association

with typhoid and paratyphoid fever, osteomyelitis, otitis media and puerperal

sepsis. it may be associated with pancreatic necrosis or other intraabdominal

infection. An abscess may rupture and form a left subphrenic abscess or result in

diffuse peritonitis.

Treatment involves that of the underlying cause and percutaneous drainage of

the splenic abscess under radiological guidance is normally required.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis of the spleen may produce portal hypertension or, rarely, cold

abscess. Treatment with anti-tuberculous drugs will normally produce

improvement. Splenectomyis not normally required and is made difficult by the

inflammatory adhesions.

Causes of splenic enlargement.

Infective Bacterial Typhoid and paratyphoid Typhus Tuberculosis

Septicaemia Splenic abscess Spirochaetal Weil’s disease Syphilis

Viral Infectious mononucleosis

HIV-related thrombocytopenia

Protozoal and parasitic Malaria Schistosomiasis Trypanosomiasis

Kala-azar Hydatid cystc

Tropical splenomegaly

Blood disease Acute leukaemia Chronic leukaemia Pernicious anaemia

Polycythaemia vera Erythroblastosis fetalis Idiopathic thrombocytopenic

purpurac Hereditary spherocytosis Autoimmune haemolytic

anaemiaThalassaemia

Sickle cell disease

Metabolic Rickets Amyloid Porphyria

Gaucher’s diseaseb

Circulatory Infarct Portal hypertension Segmental portal hypertension

(Pancreatic carcinoma, splenic vein thrombosis)

Collagen disease

Still’s disease Felty syndrome

Non-parasitic cysts Congenital Acquired

Neoplastic Angioma Primary fibrosarcoma

Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Other lymphomas Myelofibrosis

.

Leukaemia

Leukaemia should be considered in the differential diagnosis of splenomegaly

and the diagnosis is made by examining a blood or marrow film. Splenectomy is

reserved for hypersplenism that occurs during the chronic phase of chronic

granulocytic leukaemia.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

In most cases of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), the low platelet

count results from the development of antibodies to specific platelet membrane

glycoproteins that damage the patient’s own platelets. It is also known as

immune and autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura. It is defined as isolated

thrombocytopenia with normal bone marrow and the absence of other causes of

thrombocytopenia. Two distinct clinical types are evident: the acute condition in

children and a chronic condition in adults.

Clinical features

The adult form normally affects females between the ages of 15 and 50 years,

although it can be associated with other conditions, including systemic lupus

erythematosus, chronic lymphatic leukaemia and Hodgkin’s disease. The

childhood form presents before the age of five years. Purpuric patches

(ecchymoses) occur on the skin and mucous membranes. There is a tendency to

spontaneous bleeding from mucous membranes (e.g. epistaxis); in women,

menorrhagia and the prolonged bleeding of minor wounds are common.

Although intracranial haemorrhage is also uncommon, it is the most frequent

cause of death. The diagnosis is made based upon the presence of cutaneous

ecchymoses and a positive tourniquet test. The spleen is palpable in fewer than

10 per cent of patients, and the presence of gross splenic enlargement should

raise the suspicion of an alternative diagnosis.

Investigations Coagulation studies are normal, and a bleeding time is not

helpful in diagnosis. Platelet count in the peripheral blood film is reduced

(usually <60 × 109/L). Bone marrow aspiration reveals a plentiful supply of

platelet-producing megakaryocytes.

Treatment

The course of the disease differs in children and adults. The disease regresses

spontaneously in 75 per cent of paediatric cases following the initial attack.

Short courses of corticosteroids in both adult and child are usually followed by

recovery. Prolonged steroid therapy should not be continued if this does not

produce remission. Splenectomy is usually recommended if a patient has two

relapses on steroid therapy or if the platelet count remains low. Generally, this is

indicated where the ITP has persisted for more than 6–9 months.

Haemolytic anaemias

There are four causes of haemolytic anaemia that are generally amenable to

splenectomy.

Hereditary spherocytosis

characterised by the presence of spherocytic red cells, caused by various

molecular defects in the genes that code for proteins are necessary to maintain

the normal biconcave shape of the erythrocyte. Spherocytosis arises essentially

from an increase in permeability of the red cell membranes to sodium.

The clinical presentation is generally in childhood, but may be delayed until

later life. Mild intermittent jaundice is associated with mild anaemia,

splenomegaly and gallstones.

.

All patients with hereditary spherocytosis should be treated by splenectomy but,

in juvenile cases, this is generally delayed until six years of age to minimise the

risk of post-splenectomy infection, but before gallstones have had time to form.

Ultrasonography should be performed preoperatively to determine the presence

or absence of gallstones.

Acquired autoimmune haemolytic anaemia

This condition is divided into immune and non-immune mediated forms. It may

arise following exposure to agents such as chemicals, infection or drugs, e.g.

alpha-methyldopa, or be associated with another disease (e.g. systemic lupus

erythematosus).In half the patients, the spleen is enlarged and, in 20 per cent of

cases, pigment gallstones are present.

. Splenectomy should, however, be considered if corticosteroids are ineffective,

when the patient is developing complications from long-term steroid treatment

or if corticosteroids are contraindicated. Eighty per cent of patients respond to

splenectomy.

Sickle cell disease

The diagnosis is made by the finding of characteristic sickle-shaped cells on

blood film, , haemoglobin electrophoresis.

Hypoxia that provokes a sickling crisis should be avoided and is particularly

relevant in patients undergoing general anaesthesia. Adequate hydration and

partial exchange transfusion may help in a crisis. Splenectomy is of benefit in a

few patients in whom excessive splenic sequestration of red cells aggravates the

anaemia. Chronic hypersplenism usually occurs in late childhood or

adolescence, although Streptococcus pneumoniae infection may precipitate an

acute form in the first five years of life

.

Hypersplenism due to portal hypertension

Splenomegaly is an invariable feature of portal hypertension and results in the

thrombocytopenia and granulocytopenia observed in these patients. These may

be improved if the portal hypertension is relieved by shunt surgery or liver

transplantation. Splenectomy would normally be required only in those patients

whose segmental portal hypertension has resulted in symptomatic

oesophagogastric varices.

NEOPLASMS

Haemangioma is the most common benign tumour of the spleen and may rarely

develop into a haemangiosarcoma that is managed by splenectomy. The spleen

is rarely the site of metastatic disease. Lymphoma is the

most common cause of neoplastic enlargement, and splenectomy may play a

part in its management. Splenectomy may be required to achieve a diagnosis in

the absence of palpable lymph nodes or to relieve the symptoms of gross

splenomegaly. Its use has been restricted to those patients in whom a definite

histological diagnosis of intra-abdominal disease will affect management. Thus,

selected patients with stage IA or IIA Hodgkin’s disease may be candidates for

staging laparotomy or laparoscopy. In the absence of obvious liver or intra-

abdominal nodal disease, splenectomy is an integral part of the staging

procedure to exclude splenic involvement, which would alter the method of

treatment.

SPLENECTOMY

The common indications for splenectomy are:

•

trauma resulting from an accident or during a surgical procedure, as for

example during mobilisation of the oesophagus, stomach, distal pancreas or

splenic flexure of the colon;

•

removal en bloc with the stomach as part of a radical gastrectomy or with the

pancreas as part of a distal or total pancreatectomy;

•

to reduce anaemia or thrombocytopenia in spherocytosis, idiopathic

thrombocytopenic purpura or hypersplenism;

•

in association with shunt or variceal surgery for portal hypertension

Preoperative preparation

In the presence of a bleeding tendency, transfusion of blood, fresh-frozen

plasma, cryoprecipitate or platelets may be required. Coagulation profiles should

be as near normal as possible at operation, and platelets should be available for

patients with thrombocytopenia at operation and in the early postoperative

period. Antibiotic prophylaxis appropriate to the operative procedure should be

given and consideration should be given to the risk of post-splenectomy sepsis

Technique of open splenectomy

Most surgeons use a midline or transverse left subcostal incision for open

splenectomy

.

In elective splenectomy, the gastrosplenic ligament is opened up, and the short gastric

vessels are divided. The splenic vessels at the superior border of the pancreas are suture-ligated. The posterior

surface of the spleen is exposed, the posterior leaf of the lienorenal ligament divided with long curved scissors,

and the spleen rotated medially along with the tail and body of the pancreas. The pancreas is separated from the

hilar vessels, which are ligated and divided.

Accessory splenic tissue in the splenic hilum or

omentum should be excluded by a careful search at operation

Postoperative complications

Immediate complications specific to splenectomy include haemorrhage resulting

from a slipped ligature. Haematemesis from gastric mucosal damage and gastric

dilatation is uncommon. Left basal atelectasis is common, and a pleural effusion

may be present. Adjacent structures at risk during the procedure include:

the stomach and pancreas. A fistula may result from damage to the greater

curvature of the stomach during ligation of the short gastric vessels. Damage to

the tail of the pancreas may result in pancreatitis, a localised abscess or a

pancreatic fistula.

Postoperative thrombocytosis may arise and, if the blood platelet count exceeds

1 × 10

6

/mL, prophylactic aspirin is recommended to prevent axillary or other

venous thrombosis.

Post-splenectomy septicaemia may result from Streptococcus pneumoniae,

Neisseria meningitides, Haemophilus influenzae and Escherichia coli.

The risk is greater in the young patient, in splenectomised patients treated with

chemoradiotherapy and in patients who have undergone splenectomy for

thalassaemia,, sickle cell disease and autoimmune anaemia or

thrombocytopenia.

Opportunist post-splenectomy infection (OPSI) is a major concern, most

infections after splenectomy could be avoided through offering patients

appropriate and timely immunisation, antibiotic prophylaxis, education and

prompt treatment of infection.

It is thought that children who have undergone splenectomy before the age of

five years should be treated with a daily dose of penicillin until the age of ten

years. Prophylaxis in older children should be continued at least until the age of

16 years, but its use is less well defined in adults.

As the risk of overwhelming sepsis is greatest within the first

2–3 years after splenectomy, it seems reasonable to give prophylaxis

during this time. However, all patients with compromised

immune function should receive prophylaxis. Satisfactory oral

prophylaxis can be obtained with penicillin, erythromycin or

amoxicillin, or co-amoxiclav. Suspected infection can be treated

intravenously with these same antibiotics and cefotaxime, ceftriaxone

or chloramphenicol in patients allergic to penicillin

and cephalosporins

vaccinations should be administered at least 2 weeks before elective surgery

or as soon as possible after recovery from surgery but before discharge from

hospital. Pneumococcal vaccination is recommended in those patients aged

over two years. Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccination is recommended

irrespective of age

In the trauma victim, vaccination can be given in the postoperative period,

and the resulting antibody levels will be protective in the majority of cases.