Respiratory Diseases in

Pregnancy

Dr.Nadia Mudher Al-Hilli

FICOG

Assistant Prof at

Department of Obs&Gyn

College of Medicine

University of babylon

Objectives

Learn how to deal with common respiratory

problems during pregnancy including:

Pneumonia

Asthma

the new world wide infection with Corona Virus

( COVID-19 )

Physiological changes in pregnancy

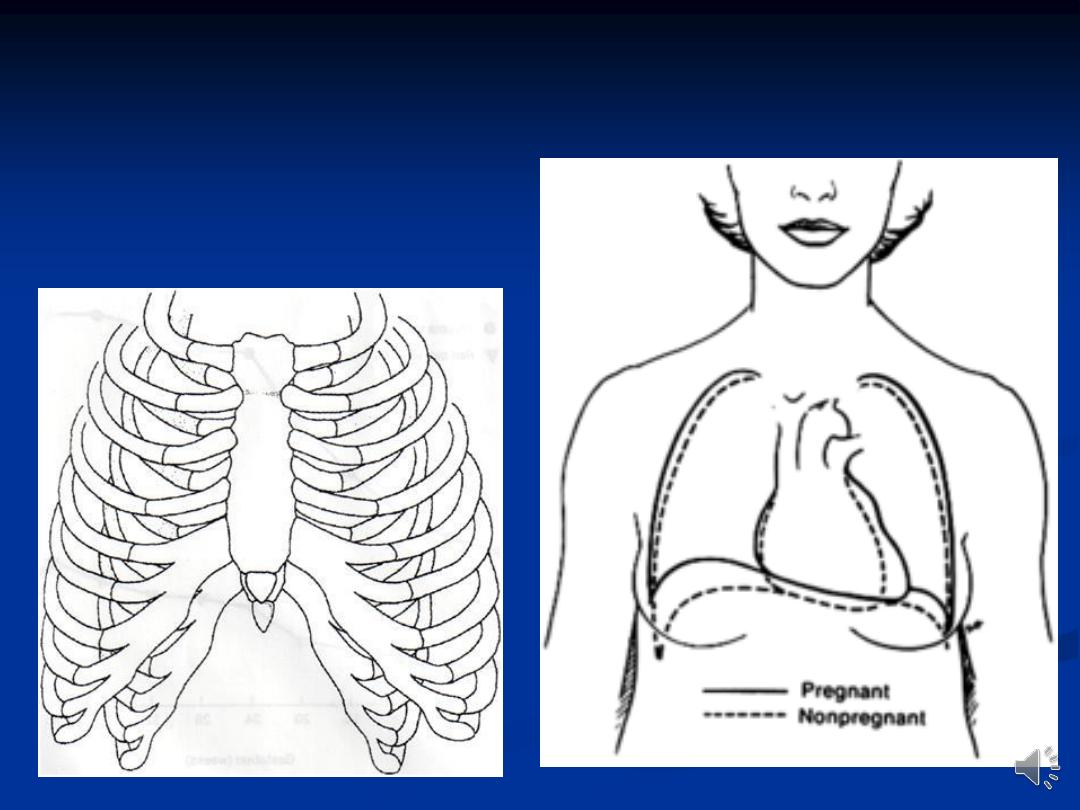

Dyspnea is experienced by approximately half of all

pregnant women by 20 weeks gestation because of

high progesterone levels which acts via the

Hypothalamus to increase respiratory drive.

Anatomically, the lower chest wall circumference

increases by 5-7 cm, the diaphragm is elevated 4-5

cm by term & the costal angle widens. These

changes occur due to the pressure from the expanding

uterus & the relaxation of thoracic ligaments.

Respiratory infection

pregnancy is a significant risk factor for the development of

severe respiratory disease attributable to viral infection.

a seasonal flu vaccine is recommended in pregnancy.

Viral pneumonia follows a more complicated course in

pregnancy and women often decompensate more quickly.

Prompt treatment and early involvement of respiratory and

infectious disease specialists in addition to the intensive care

is essential.

Bacterial pneumonia should be treated with penicillin or

cephalosporins usually the first choice, and erythromycin

used if atypical organisms are suspected.

Pneumonia: warning signs

Respiratory rate >30/minute.

Hypoxaemia; pO2 <7.9 kPa on room air.(

normal >10.5 kpa

Acidosis; pH <7.3. (normal 7.35-7.45)

Hypotension.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Elevated blood urea.

Evidence of multiple organ failure.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection in

Pregnancy

Novel coronavirus (SARS-COV-2) is a new strain of

coronavirus causing COVID-19

Pregnant women do not appear to be more likely to

contract the infection than the general population.

Vertical Transmission: antepartum or

intrapartum is probable.

Effect on the mother: majority mild or

moderate cold/flu like symptoms. changes to

their immune system in pregnancy can be

associated with more severe symptoms.

Effect on the fetus: no increased risk of

miscarriage or early pregnancy loss in relation to

COVID-19. no teratogenic effects.

Attendance for routine antenatal care in women with

suspected or confirmed COVID-19: should be

delayed until after the recommended period of

isolation

Women attending for intrapartum care with

suspected/confirmed COVID-19 and no/mild

symptoms: encouraged to remain at home (self-

isolating) in early (latent phase) labour.

When attend the maternity unit, settled in an isolation

room, a full maternal and fetal assessment should be

conducted to include:

• Assessment of the severity of COVID-19 symptoms

should follow a multi-disciplinary team approach

• Maternal observations including temperature,

respiratory rate and oxygen saturations

• Confirmation of the onset of labour

• Electronic fetal monitoring using cardiotocograph

(CTG)

If the woman has signs of sepsis, investigate & treat but

also consider active COVID-19 as a cause of sepsis.

Mode of birth should not be influenced by the presence

of COVID-19, unless the woman’s respiratory condition

demands urgent delivery.

epidural or spinal analgesia or anaesthesia are not

contraindicated in the presence of coronaviruses.

They minimise the need for general anaesthesia if urgent

delivery is needed, and better than Entonox which may

increase aerosolisation and spread of the virus.

If Entonox is used then the breathing system must

contain a filter to prevent contamination with the virus.

In case of deterioration in the woman’s

symptoms, decision of proceeding to emergency

caesarean birth if this is likely to assist efforts to

resuscitate the mother

steroids for fetal lung maturation cause no harm

in the context of COVID-19.

Asthma in Pregnancy

The prevalence of asthma in pregnancy is about

3 –12 per

cent.

Effect of pregnancy on asthma severity:

stable in one-third of women, worsens in another third and

improves in the remaining third.

most episodes occur between 24 and 36 weeks of pregnancy

The potential benefit of pregnancy-induced immune system

modulation & progesterone-mediated bronchodilatation

may be opposed by the reluctance of patient & physician to

treat asthma for the fear of harming the fetus through drug

exposure.

The effect of asthma on pregnancy:

Severe & poorly controlled asthma have a

detrimental effect on pregnancy including:

intrauterine growth restriction

hypertensive disorders

preterm labour

intrauterine fetal death.

Labour and delivery : are not usually affected by

asthma and attacks are uncommon in labour.

Postpartum, there is no increased risk of

exacerbations and those whose asthma deteriorated

during pregnancy have usually returned to pre-

pregnancy levels by three months after birth.

Management of asthma in pregnancy:

Same as in non-pregnant patient. Prevention is the

key & known triggers of exacerbations should be

avoided .

Short-acting & long-acting beta2-agonists, inhaled

steroids & theophylline can be used in pregnancy.

These drugs will suffice for mild to moderate

asthmatics

Epinephrine should be avoided in the pregnant

patient. it can lead to possible congenital

malformations, fetal tachycardia, and

vasoconstriction of the uteroplacental circulation

Women with more severe asthma who have

stabilized on leukotriene receptor antagonist

(montelukast) may continue them through out

pregnancy.

Prednisolone is the oral steroid of choice in

pregnancy, as 88 % of it is metabolized by the

placenta, limiting fetal exposure.

The teratogenic risk & possible harmful fetal

effects of maternal steroid treatment remain an

area of controversy.

Managing pregnancy in asthmatic patients:

For those with poorly controlled or severe

asthma , care should be multidisciplinary.

Baseline investigations, such as peak flow

measurements should be obtained at booking.

Medical treatment should be optimized, with

repeated reassurance about the use of

necessary drugs in pregnancy.

Women taking Prednisolone should be

screened for glucose intolerance

Labour & delivery:

Parenteral steroid cover may be needed for those who are on

regular steroids

regular medications should be continued throughout labour .

bronchoconstrictors, such as ergometrine or prostaglandin

F2α, should be avoided.

Adequate hydration is important.

regional anaesthesia favoured over general, to decrease the

risk of bronchospasm, provide adequate pain relief and to

reduce oxygen consumption and minute ventilation.

Breast feeding

is not contraindicated with any

of the medications used although high-dose oral

steroid use ( ≥ 40 mg per day )carries a risk of

neonatal adrenal suppression