Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Dr.Ahmed Hussein Jasim (F.I.B.M.S) (respiratory)

COPD) is a preventable and treatable disease characterised by persistent

airflow limitation that is usually progressive, and associated with an

enhanced chronic inflammatory response in the airways and the lung to

noxious particles or gases.

Related diagnoses include

chronic bronchitis

(cough and sputum on most

days for at least 3 months, in each of 2 consecutive years) and

emphysema

(abnormal permanent enlargement of the airspaces distal to

the terminal bronchioles, accompanied by destruction of their walls and

without obvious fibrosis).

•

Extra-pulmonary effects include weight loss and skeletal muscle dysfunction.

Commonly associated comorbid conditions include

•

cardiovascular disease,

•

cerebrovascular disease,

•

metabolic syndrome,

•

osteoporosis, depression and lung cancer.

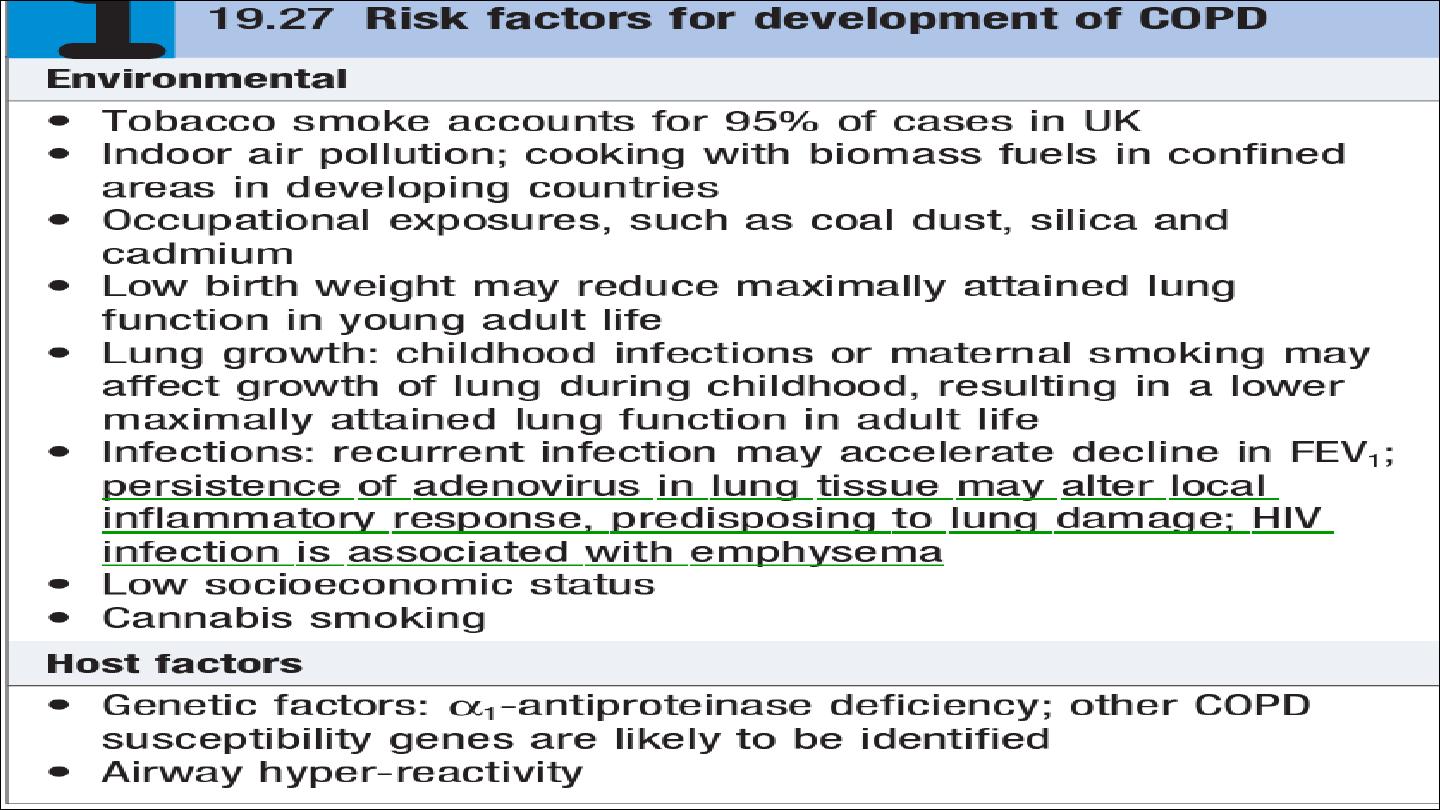

Epidemiology and aetiology

The prevalence of COPD is directly related to the prevalence of tobacco

smoking and, in low- and middle income countries and the use of biomass

fuels.

Cigarette smoking represents the most significant risk factor, and the risk

of developing COPD relates to both the amount and the duration of

smoking. It is unusual to develop COPD with less than 10 pack years (1

pack year = 20 cigarettes/day/year)

not all smokers develop the condition, suggesting that individual

susceptibility factors are important.

Pathophysiology

COPD has both pulmonary and systemic components .The presence of

airflow limitation, combined with premature airway closure, leads to gas

trapping and hyperinflation, reducing pulmonary and chest wall compliance.

Pulmonary hyperinflation also flattens the diaphragmatic muscles and leads

to an increasingly horizontal alignment of the intercostal muscles, placing

the respiratory muscles at a mechanical disadvantage.

Clinical features

COPD should be suspected in any patient over the age of 40 years who

presents with symptoms of chronic bronchitis and/or breathlessness.

Cough and associated sputum production are usually the first symptoms,

often referred to as a ‘smoker’s cough’.

Haemoptysis may complicate exacerbations of COPD but should not be

attributed to COPD without thorough investigation.

Breathlessness usually precipitates the presentation to health care. The

severity should be quantified by the modified MRC dyspnoea scale (Medical

Research Council).

Physical signs

•

Breath sounds are typically quiet.

•

Crackles may accompany infection but, if persistent, raise the possibility of

bronchiectasis.

•

Finger clubbing is not a feature of COPD and should trigger further

investigation for lung cancer or fibrosis.

•

Pitting oedema should be sought but the frequently used term ‘cor

pulmonale’ is actually a misnomer, as the right heart seldom ‘fails’ in

COPD and the occurrence of oedema usually relates to failure of salt and

water excretion by the

hypoxic hypercapnic kidney

.

Two classical phenotypes have been described: ‘pink puffers’ and ‘blue

bloaters’

The former are typically thin and breathless, and maintain a normal PaCO2

until the late stage of disease. The blue bloaters’ develop (or tolerate)

hypercapnia earlier and may develop oedema and secondary polycythaemia.

In practice, these phenotypes often overlap.

Investigations

*The diagnosis requires objective demonstration of airflow obstruction by

spirometry and is established when the post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC is less

than 70%.

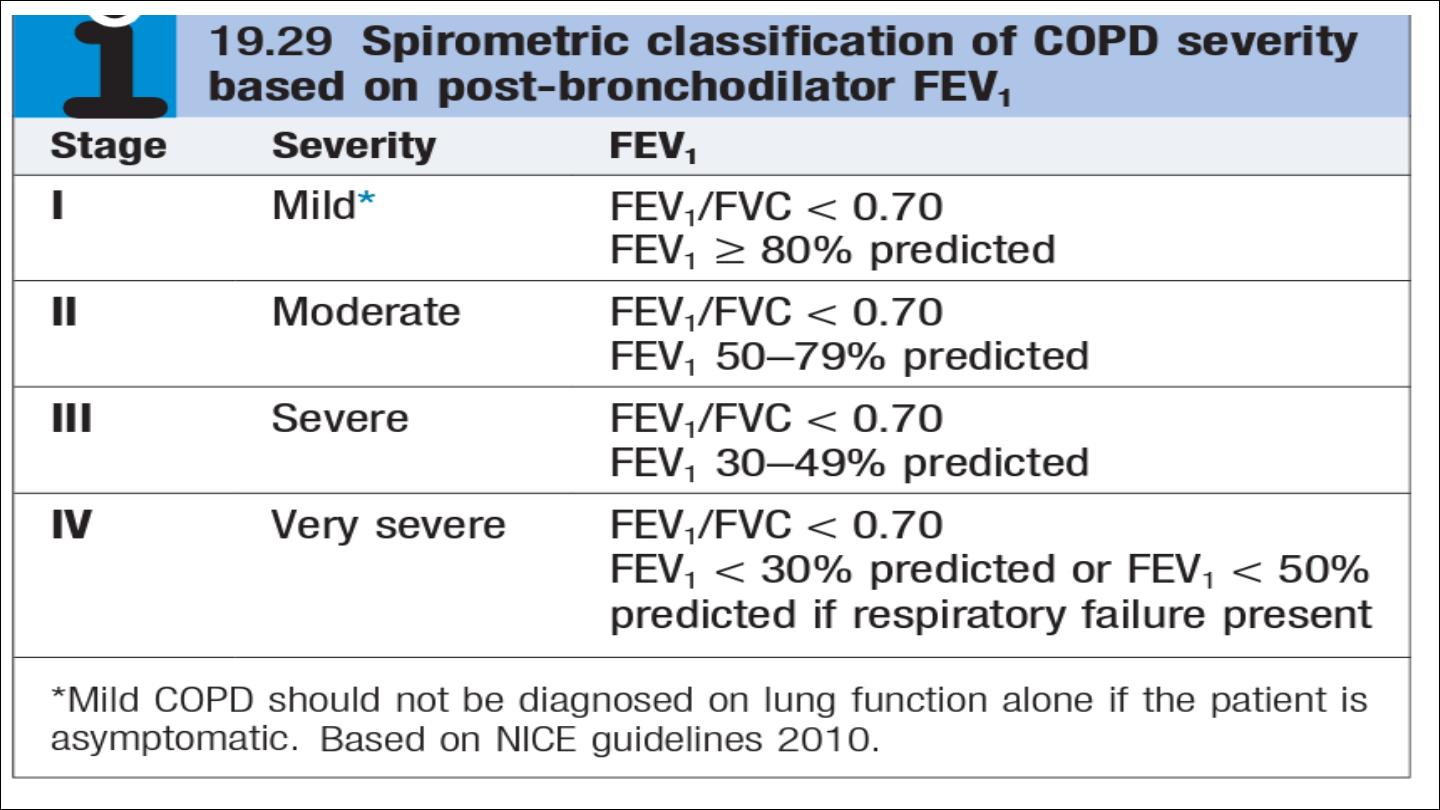

The severity of COPD may be defined in relation to the post-

bronchodilator FEV1 .

*A low peak flow is consistent with COPD but is non-specific, does not

discriminate between obstructive and restrictive disorders, and may

underestimate the severity of airflow limitation.

*Measurement of lung volumes provides an assessment of hyperinflation.

This is generally performed by using

the helium dilution techniques

. in

patients with severe COPD, and with large bullae in particular,

body

plethysmography

is preferred because the use of helium may underestimate

lung volumes. Emphysema is suggested by a low gas transfer value.

*Exercise tests provide an objective assessment of exercise tolerance and a

baseline for judging response to bronchodilator therapy or rehabilitation

programmes; they may also be valuable when assessing prognosis.

*Pulse oximetry of less than 93% may indicate the need for referral for a

domiciliary oxygen assessment.

*chest X-ray is essential to identify alternative diagnoses, such as cardiac

failure, other complications of smoking such as lung cancer, and the

presence of bullae.

*A blood count is useful to exclude anaemia or polycythaemia.

*HRCT is likely to play an increasing role in the assessment of COPD, as it

allows the detection, characterization and quantification of emphysema and

is more sensitive than a chest X-ray for detecting bullae.

*α1-antiproteinase

should

be

assayed in younger

patients

with

predominantly basal emphysema.

Management

•

possible to help breathlessness

•

reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations.

•

enhance the health status.

•

improve the prognosis.

•

Reducing exposure to noxious particles and gases, the role of smoking

in the development and progression of COPD, with advice and

assistance to help them stop.

•

Reducing the number of cigarettes smoked each day has little impact

on the course and prognosis of COPD, but complete cessation is

accompanied by an improvement in lung function and deceleration in

the rate of FEV1 decline .

Bronchodilators

Bronchodilator therapy is central to the management of breathlessness.

The inhaled route is preferred and a number of different agents,

Short-acting bronchodilators, such as the β2-agonists salbutamol and

terbutaline, or the anticholinergic ipratropium bromide, may be used for

patients with mild disease.

Longer acting bronchodilators, such as the β2-agonists salmeterol,

formoterol and indacaterol, or the anticholinergic tiotropium bromide, are

more appropriate for patients with moderate to severe disease.

Theophylline preparations improve breathlessness and quality of life, but

their use is limited by side-effects, unpredictable metabolism and drug

interactions

Corticosteroids

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) reduce the frequency and severity of

exacerbations, and are currently re commended in patients with severe

disease (FEV1 < 50%) who report two or more exacerbations requiring

antibiotics or oral steroids per year.

It is more usual to prescribe a fixed combination of an ICS and a LABA.

Oral corticosteroids are useful during exacerbations but maintenance

therapy contributes to osteoporosis and impaired skeletal muscle function

and should be avoided.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Exercise should be encouraged at all stages and patients reassured that

breathlessness, whilst distressing, is not dangerous.

Most programmes include 2–3 sessions per week for 6 and 12 weeks.