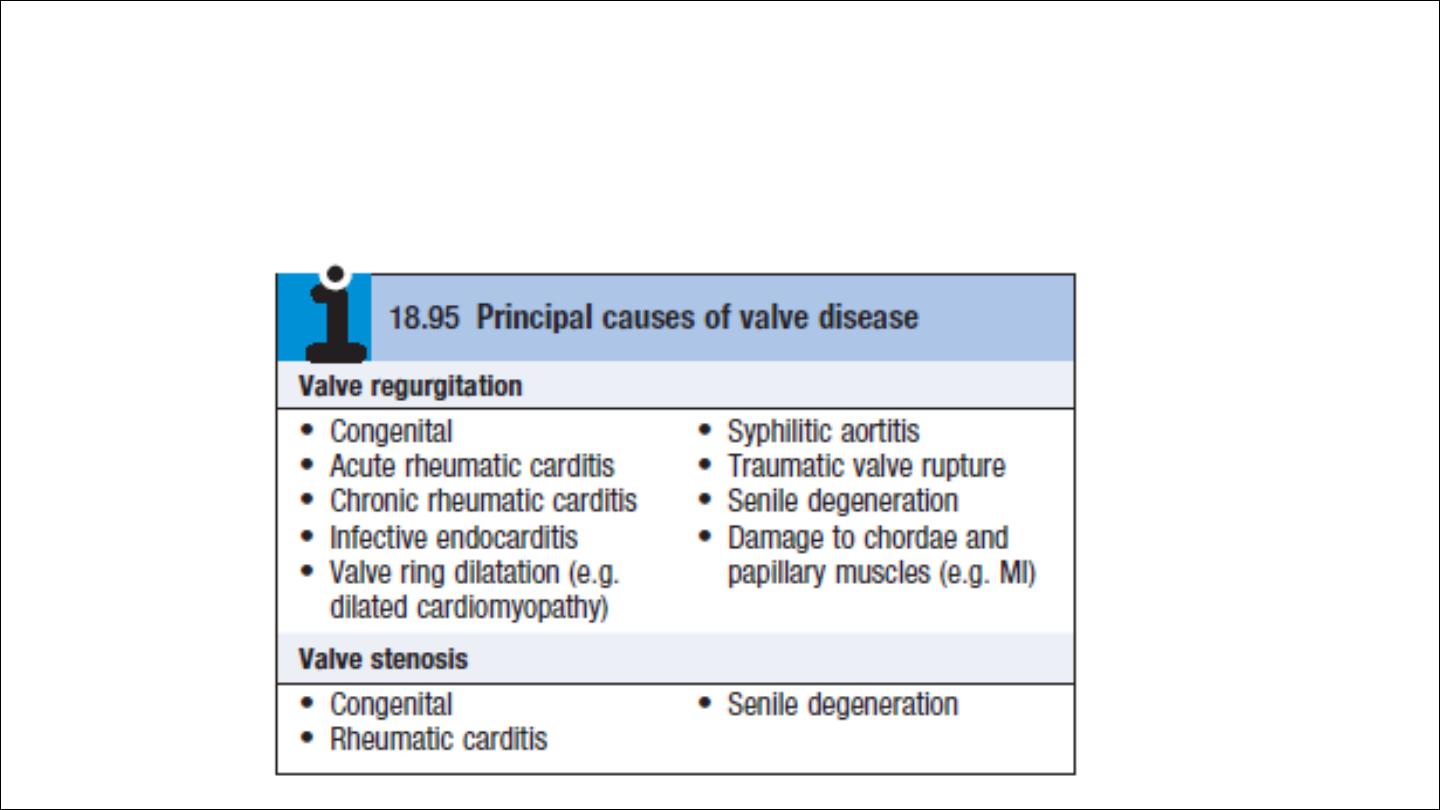

VALVULAR HEART DISEASE

1. Stenosis : the valve orifice narrowed

2. Regurgitation or reflux: the valve fail to close adequately

3.Combination of stenosis and regurgitation

Mitral valve disease

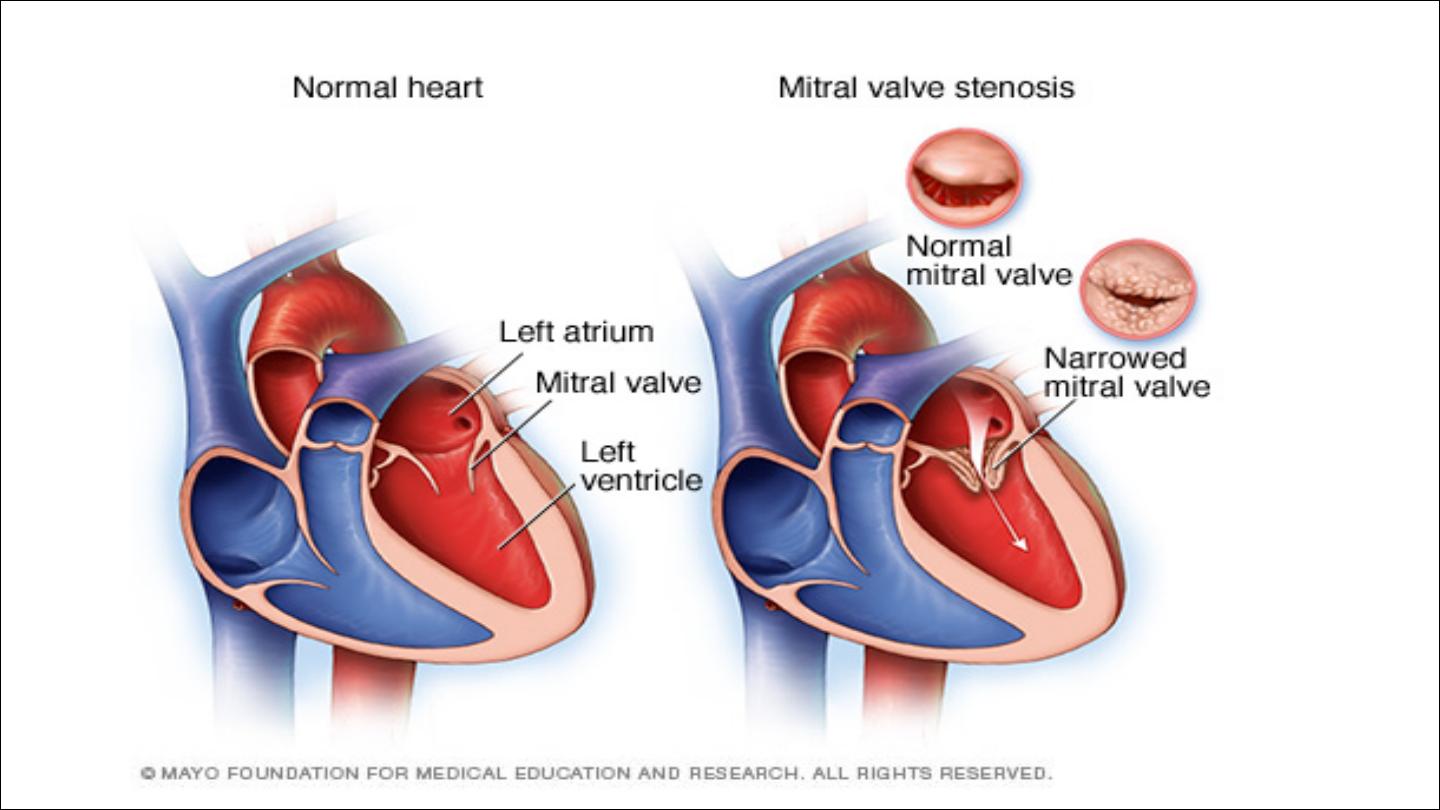

Mitral stenosis

Aetiology and pathophysiology:

•

Mitral stenosis is almost always

rheumatic

in origin

•

Senile

degenerative changes heavy calcification of the mitral valve

apparatus

•

Rarely

congenital

In rheumatic mitral stenosis, the mitral valve orifice is slowly diminished

by progressive fibrosis, thickening, calcification of the valve leaflets, and

fusion of the cusps and subvalvular apparatus.

LA → LV flow reduced, so LA pressure increase leading to pulmonary

venous congestion and breathlessness

q

Any increase in heart rate shortens diastole when the mitral valve is

open and produces a further rise in left atrial pressure. Situations that

demand an increase in cardiac output also increase left atrial

pressure, so exercise and pregnancy are poorly tolerated.

q

Normal MV orifice 5 cm 2, Symptom occur when the orifice less than

2 cm 2, Severe MS less than 1 cm 2

q

Dyspnea due to reduced lung compliance due to chronic pulmonary

venous congestion. Fatigue due to reduced CO

q

AF is common. Fewer than 20% of patients remain in sinus rhythm; many

of these have a small fibrotic LA and severe pulmonary hypertension.

Sudden rise in LA pressure → pulmonary odema.

In contrast, a more gradual rise in left atrial pressure tends to cause an

increase in pulmonary vascular resistance, which leads to pulmonary

hypertension that may protect the patient from pulmonary oedema.

Pulmonary hypertension leads to right ventricular hypertrophy and

dilatation, tricuspid regurgitation and right heart failure.

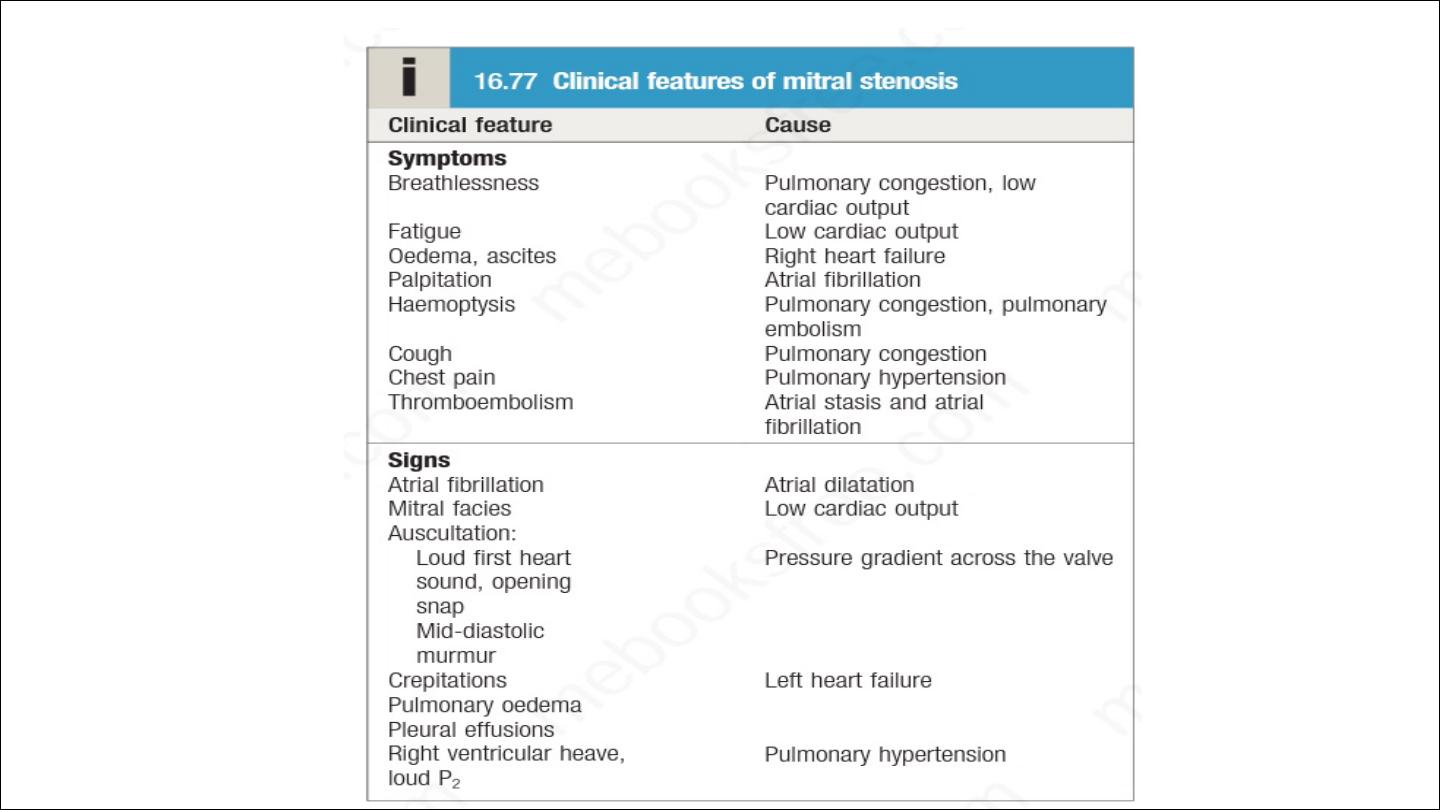

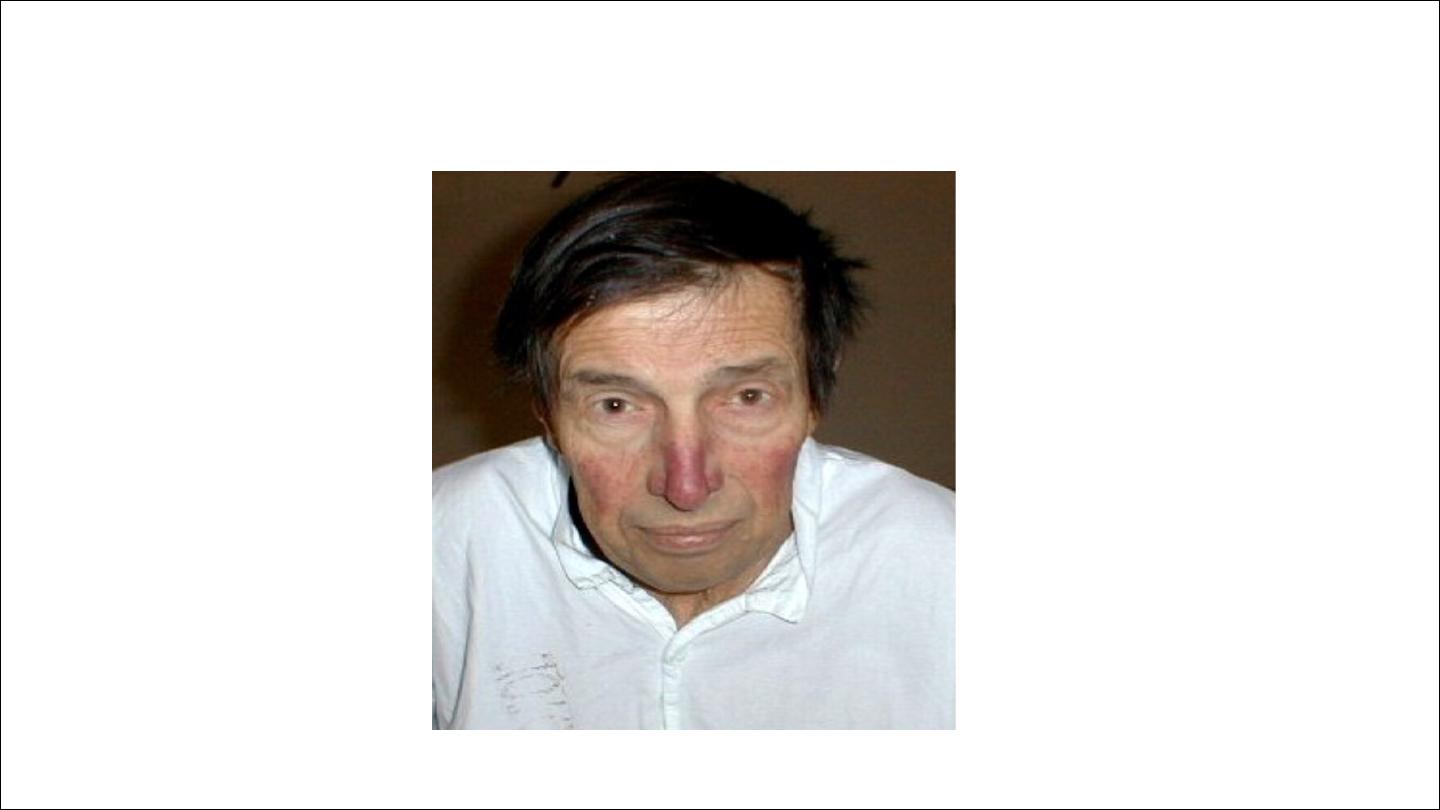

Mitral facies

Effort-related dyspnea is usually the dominant symptom . Exercise

tolerance typically diminishes very slowly over many years and patients

often do not appreciate the extent of their disability. Eventually,

symptoms occur at rest.

All patients with mitral stenosis, and particularly those with atrial

fibrillation, are at risk from left atrial thrombosis and systemic

thromboembolism.

Auscultatory finding in mitral stenosis

S 1 may be soft in heavily calcified valve

Opening snap indicate pliable leaflet, become closer to S1 as the

severity of the valve increase, absent in heavily calcified valve.

The duration of murmur increase with the severity of mitral stenosi

Clinical signs of sever MS

1. LONG RUMBLING DIASTOLIC MURMUR

2. OPENING SNAP CLOSE TO S2 OR ABSCENT

3. SIGN OF PHT, LOUD P2, RV HEAVE

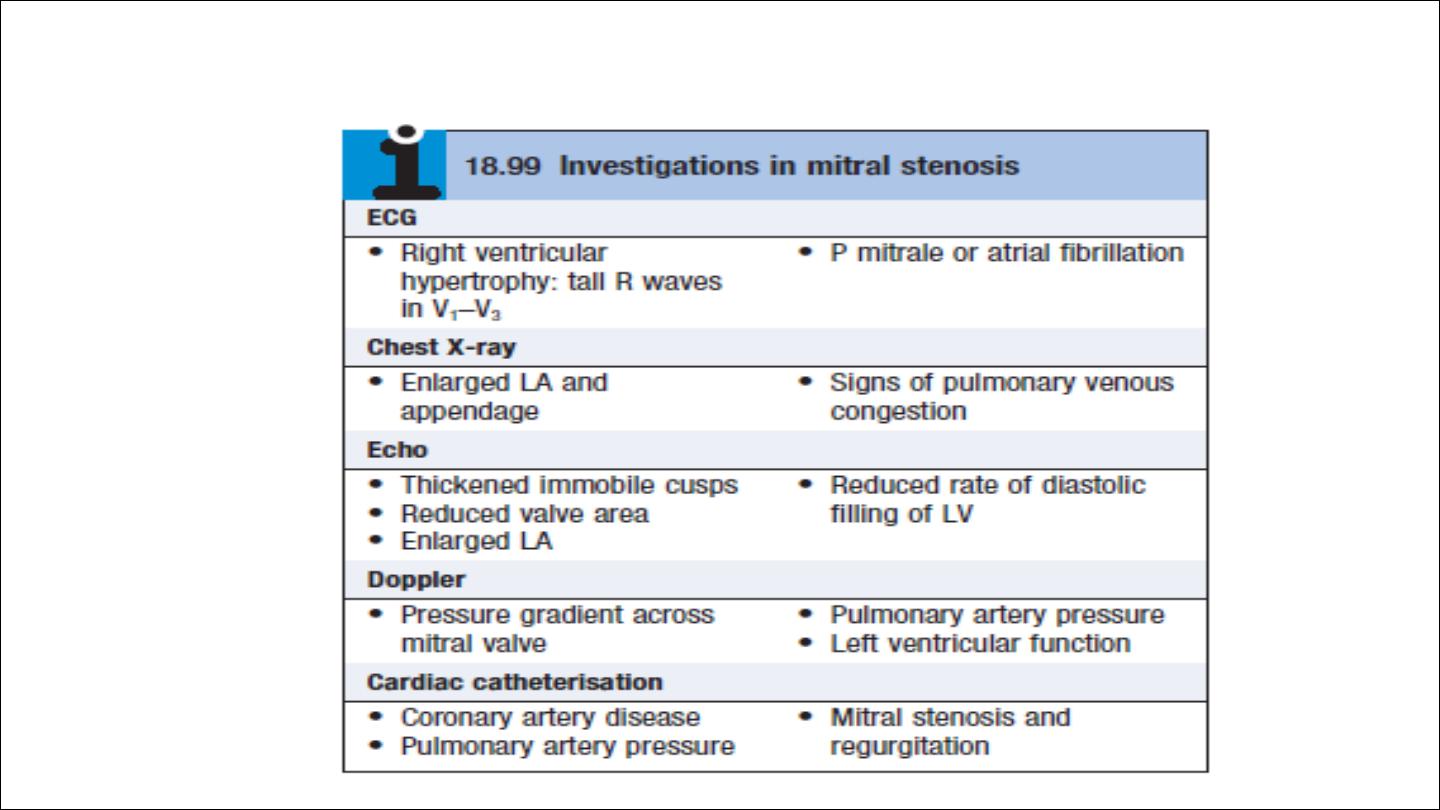

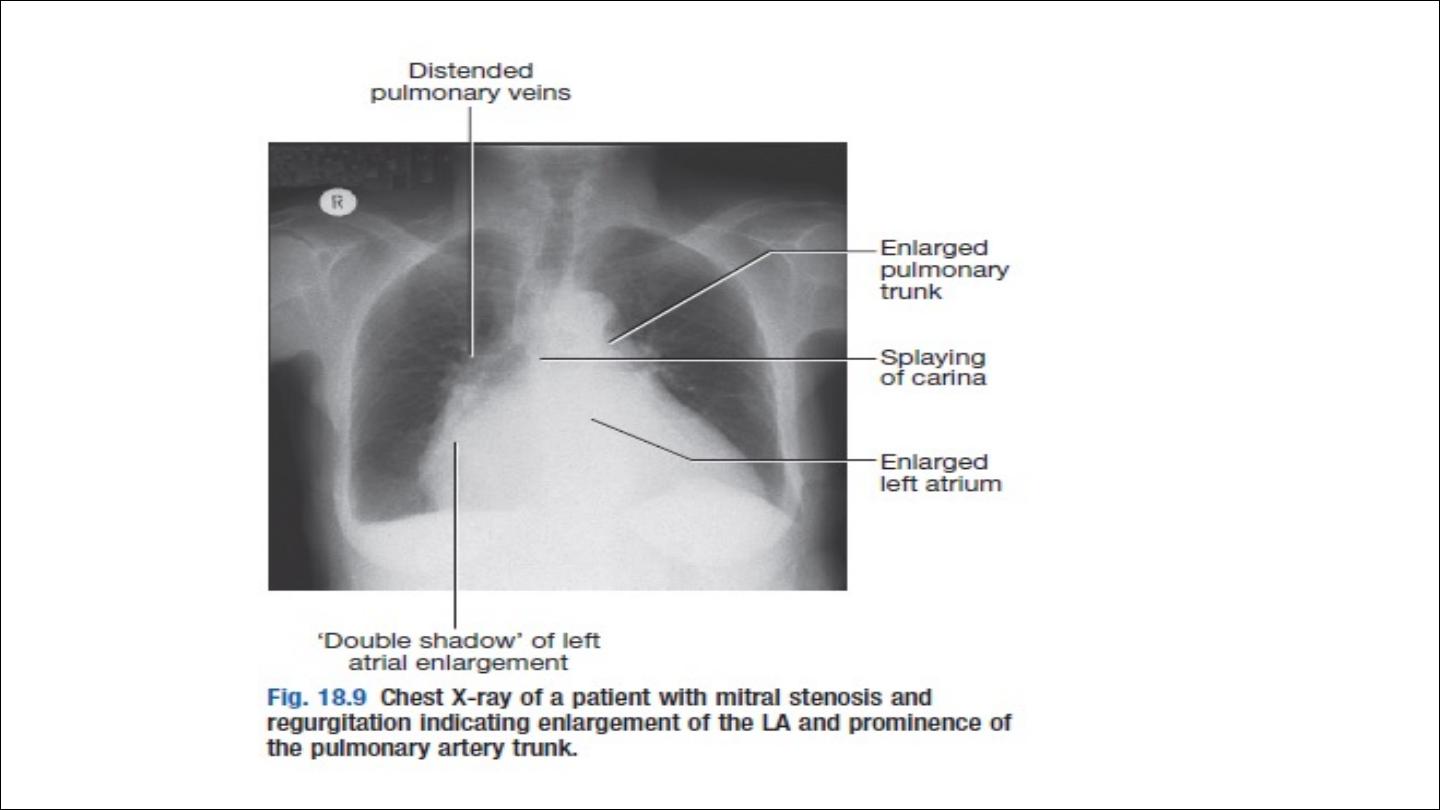

Investigation

Management

Medical treatment

1. Rate control for AF and rapid ventricular rate

2. anticoagulation; AF, thromboembolism, spontaneous echo contrast

3. Diuretics to relieve pulmonary congestion

4. Antibiotic prophylaxis against infective endocarditis is no longer

routinely recommended

•

If patients remain symptomatic despite medical treatment, intervention

include balloon valvuloplasty, mitral valvotomy or mitral valve replacement

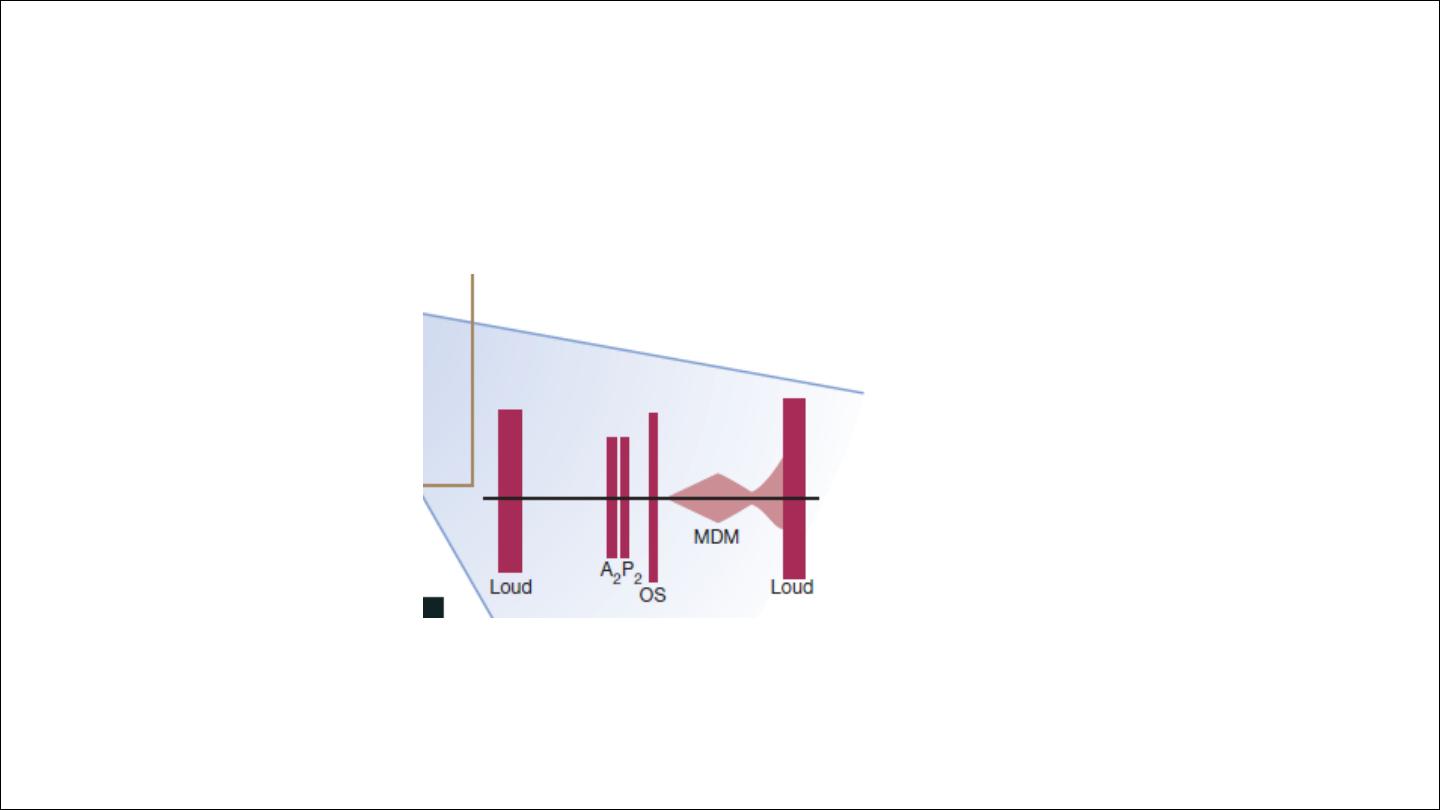

Criteria for mitral valvuloplasty

•

Significant symptoms

•

Isolated mitral stenosis

•

No (or trivial) mitral regurgitation

•

Mobile, non-calcified valve/subvalve apparatus on echo

•

LA free of thrombus

•

Follow up after balloon valvoplasty at 1 to 2 years interval as restenosis can

occur

Surgival Open or closed mitral valvotomy is acceptable alternative

Valve replacement is indicated if there is substantial mitral reflux or if the

valve is rigid and calcified

Mitral regurgitation

Aetiology and pathophysiology:

Rheumatic disease is the principal cause in countries where rheumatic

fever is common

Mitral regurgitation may also follow mitral valvotomy or valvuloplasty

.

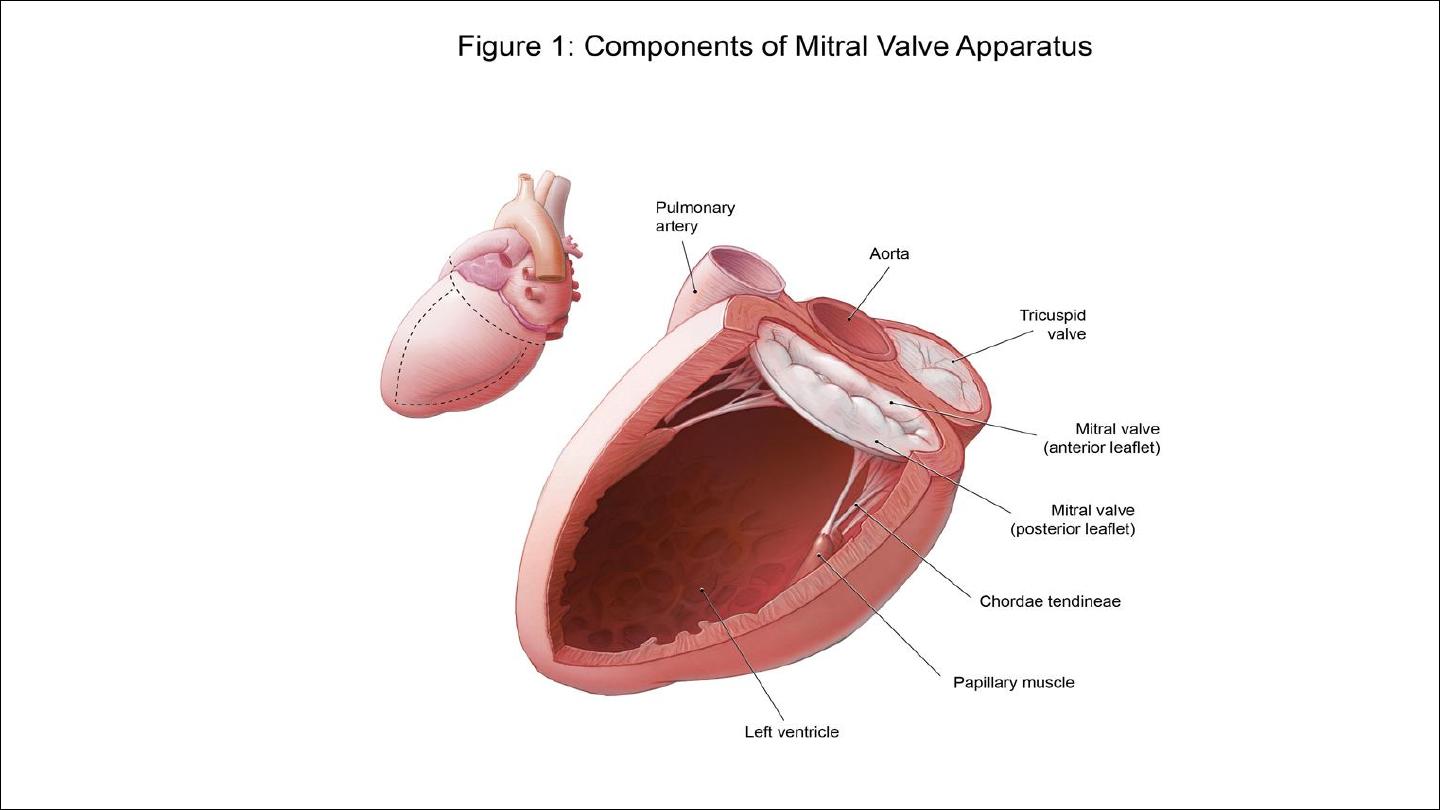

ACUTE MR

1. RUPTURE PAPILLARY MUSCLE COMPLICATING ACUTE MI

2. RUPTURE CHORDAE TENDONAE DUE TO IE OR MVP

3. IE CAUSING VALVE PERFORATION

Chronic mitral regurgitation causes gradual dilatation of the LA with

little increase in pressure and therefore relatively few symptoms.

Nevertheless, the LV dilates slowly and the left ventricular diastolic and

left atrial pressures gradually increase as a result of chronic volume

overload of the LV

In acute mitral regurgitation causes a rapid rise in left atrial pressure

(because left atrial compliance is normal) and marked symptomatic

deterioration.

•

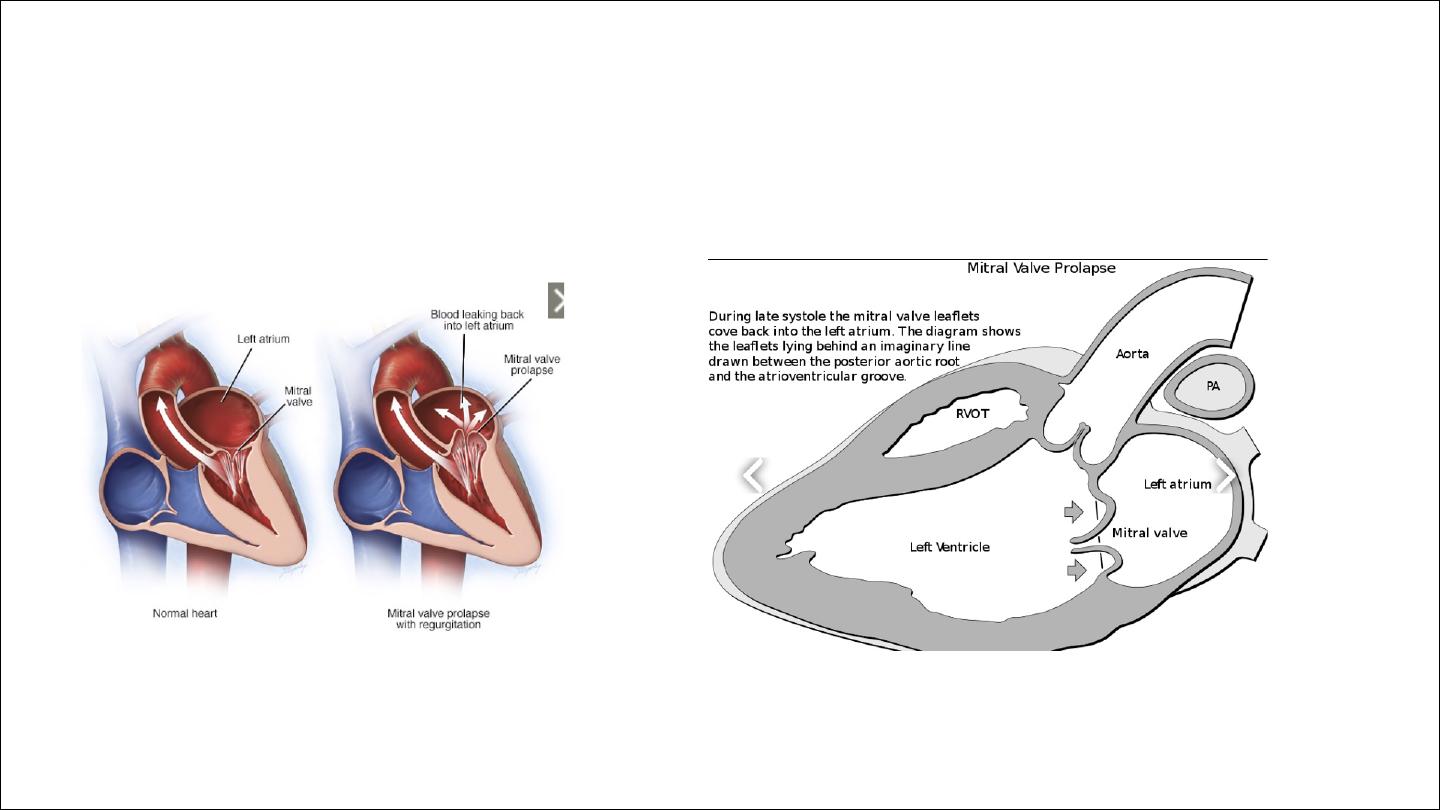

Mitral valve prolapse

This is also known as ‘floppy’ mitral valve and is one of the more

common causes of mild mitral regurgitation. It is caused by congenital

anomalies or degenerative myxomatous changes, and is sometimes a

feature of connective tissue disorders such as Marfan’s syndrome.

In its mildest forms, the valve remains competent but bulges back into

the atrium during systole, causing a mid-systolic click but no murmur.

If regurgitation occur, click followed by murmur

A click is not always audible and the physical signs may vary with both

posture and respiration. Progressive elongation of the chordae

tendineae leads to increasing mitral regurgitation, and if chordal

rupture occurs, regurgitation suddenly becomes severe. This is rare

before the fifth or sixth decade of life.

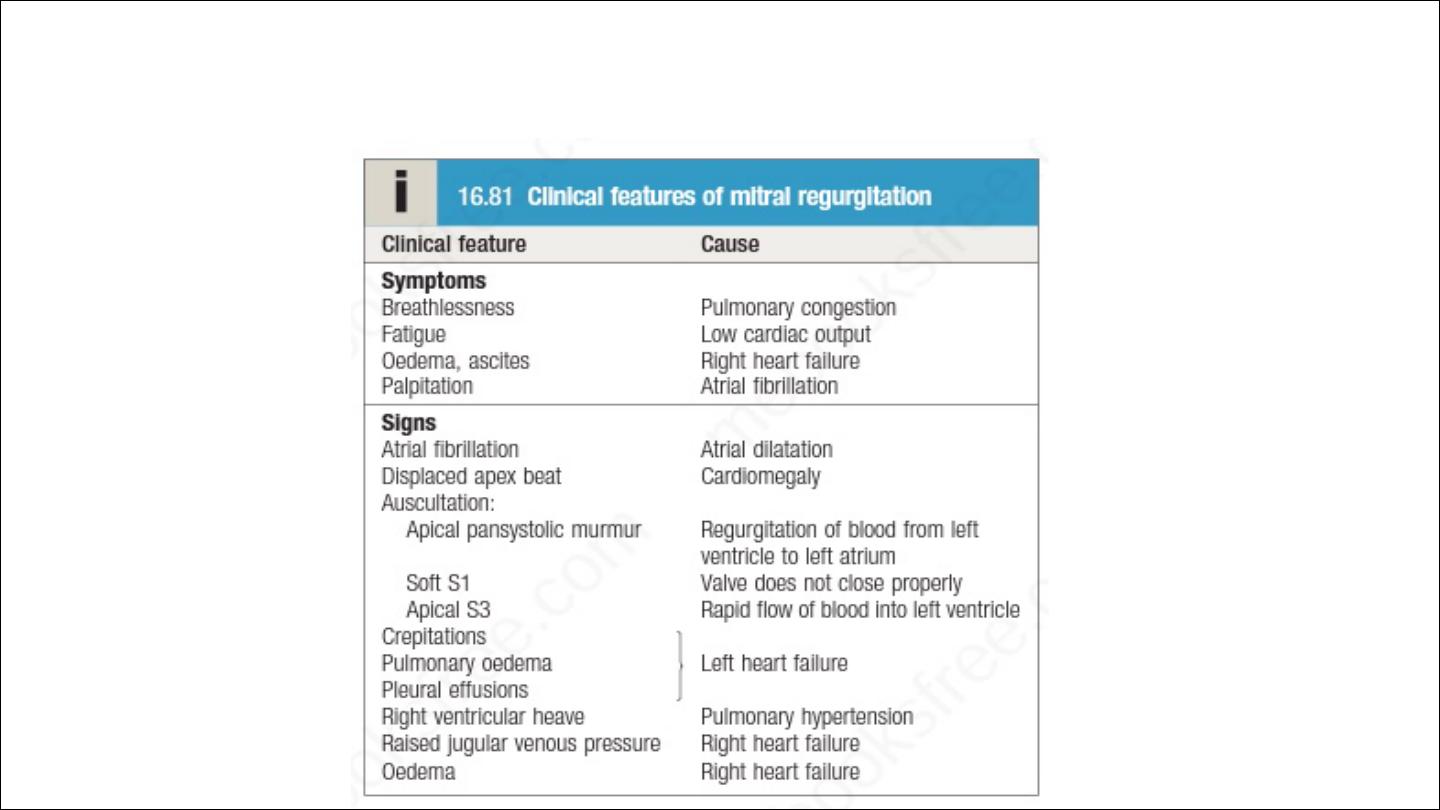

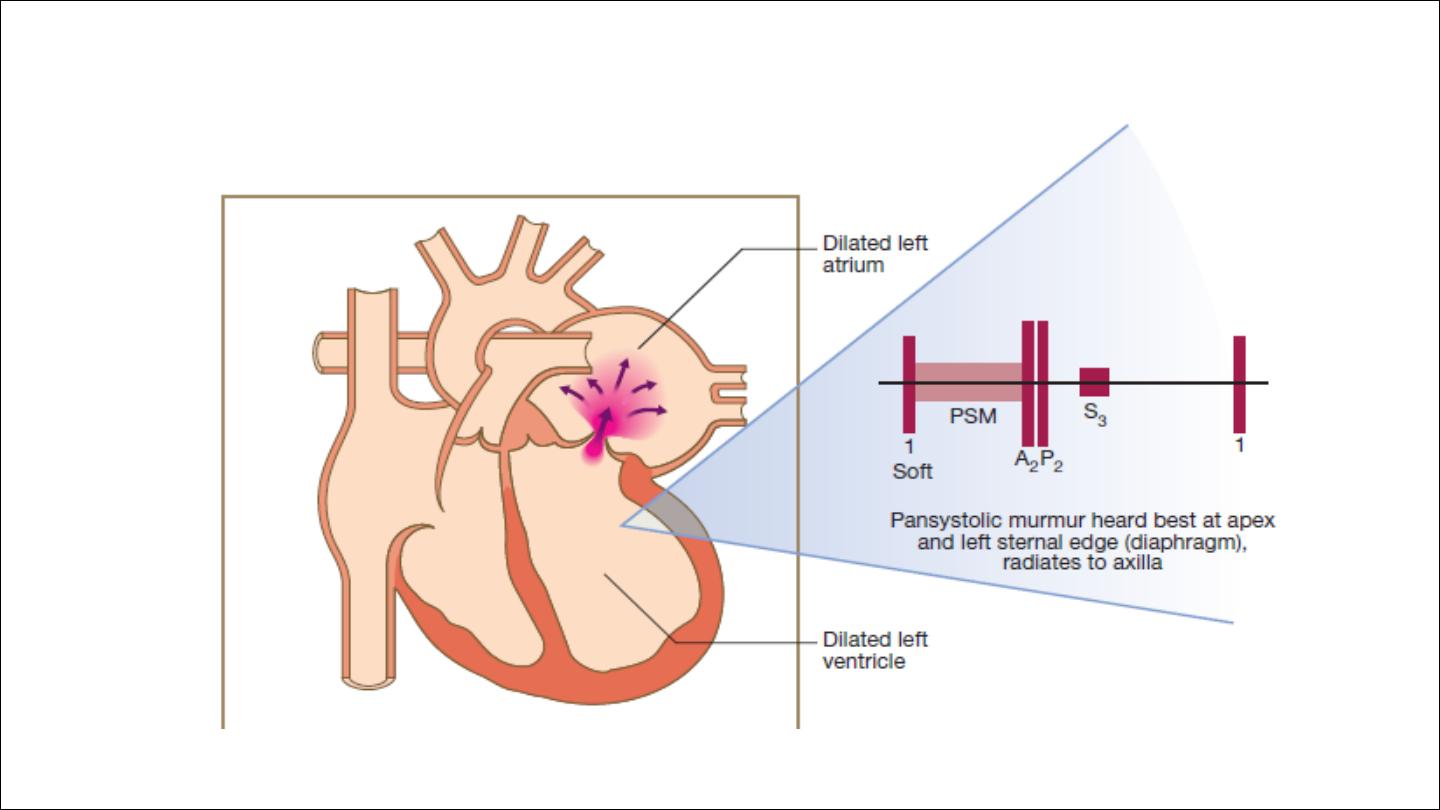

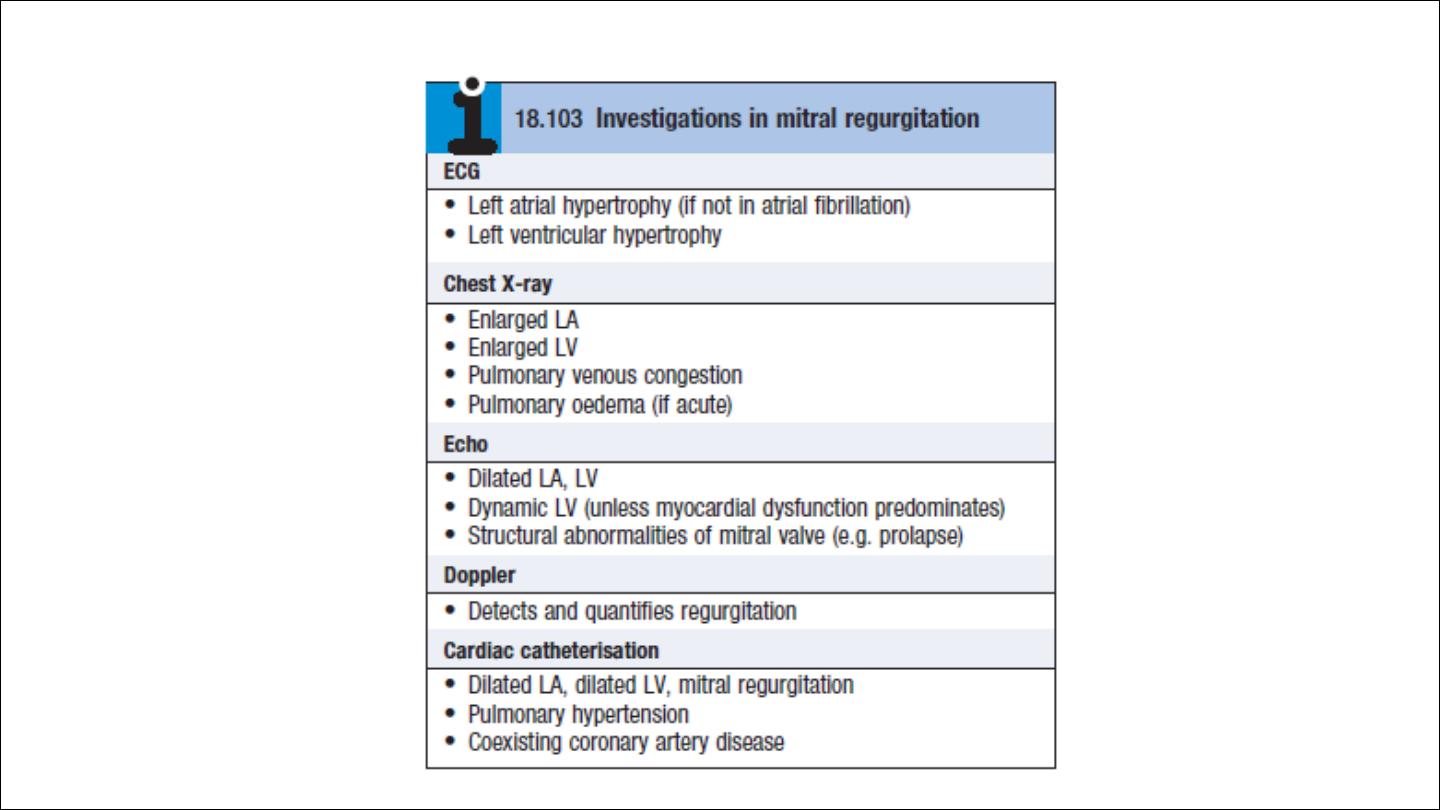

Clinical features

Symptoms depend on how suddenly the regurgitation develops

management

•

Diuretics

•

Vasodilators, e.g. ACE inhibitors

•

Digoxin if atrial fibrillation is present

•

Anticoagulants if atrial fibrillation is present

•

Surgery : repair or replacement

valve repair is used to treat mitral valve prolapse and offers many advantages

when compared to mitral valve replacement, such that it is now advocated

for severe regurgitation, even in asymptomatic patients, because results are

excellent and early repair prevents irreversible left ventricular damage

Mitral regurgitation often accompanies the ventricular dilatation and

dysfunction that are concomitants of coronary artery disease. If such

patients are to undergo coronary bypass graft surgery, it is common practice

to repair the valve and restore mitral valve function by inserting an

annuloplasty ring to overcome annular dilatation and to bring the valve

leaflets closer together.

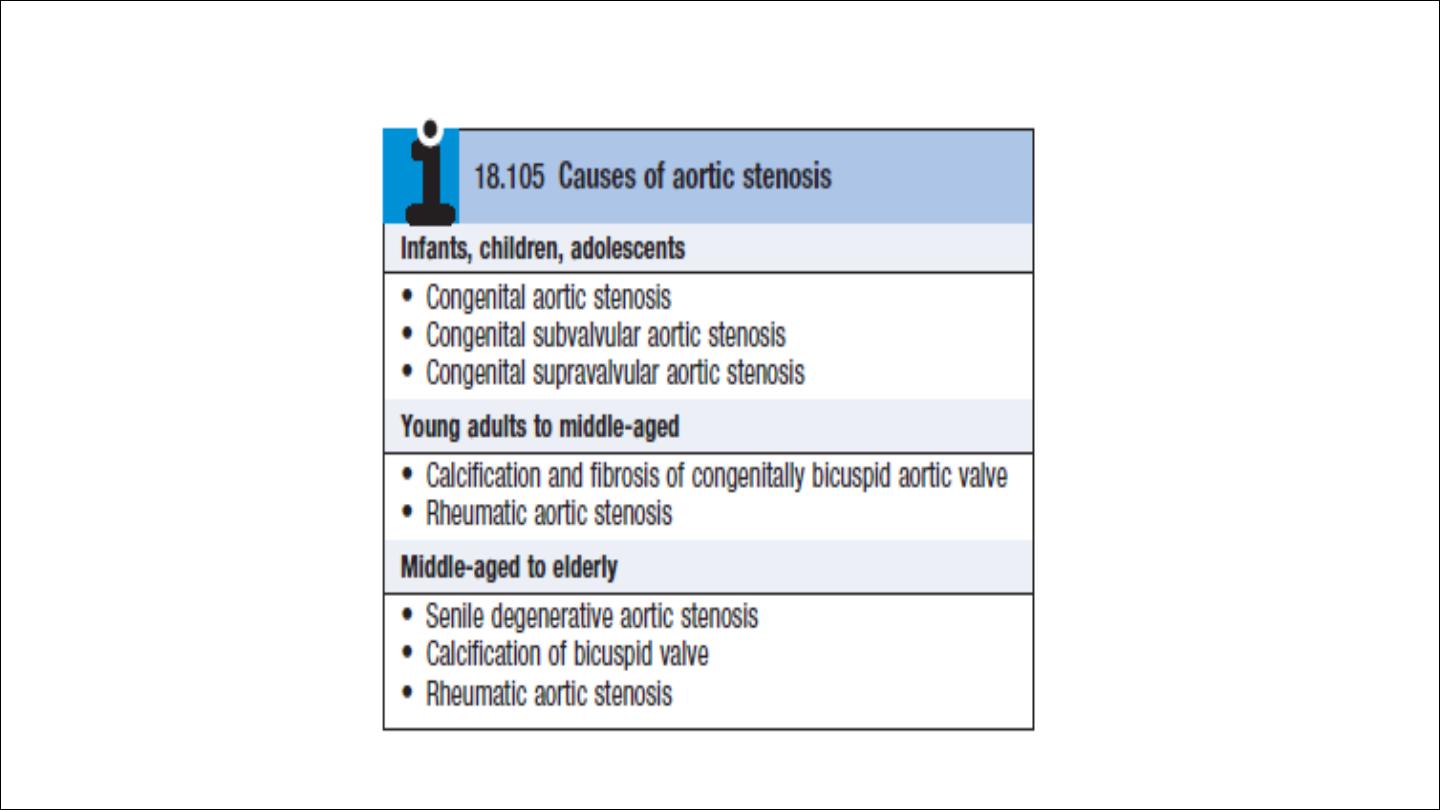

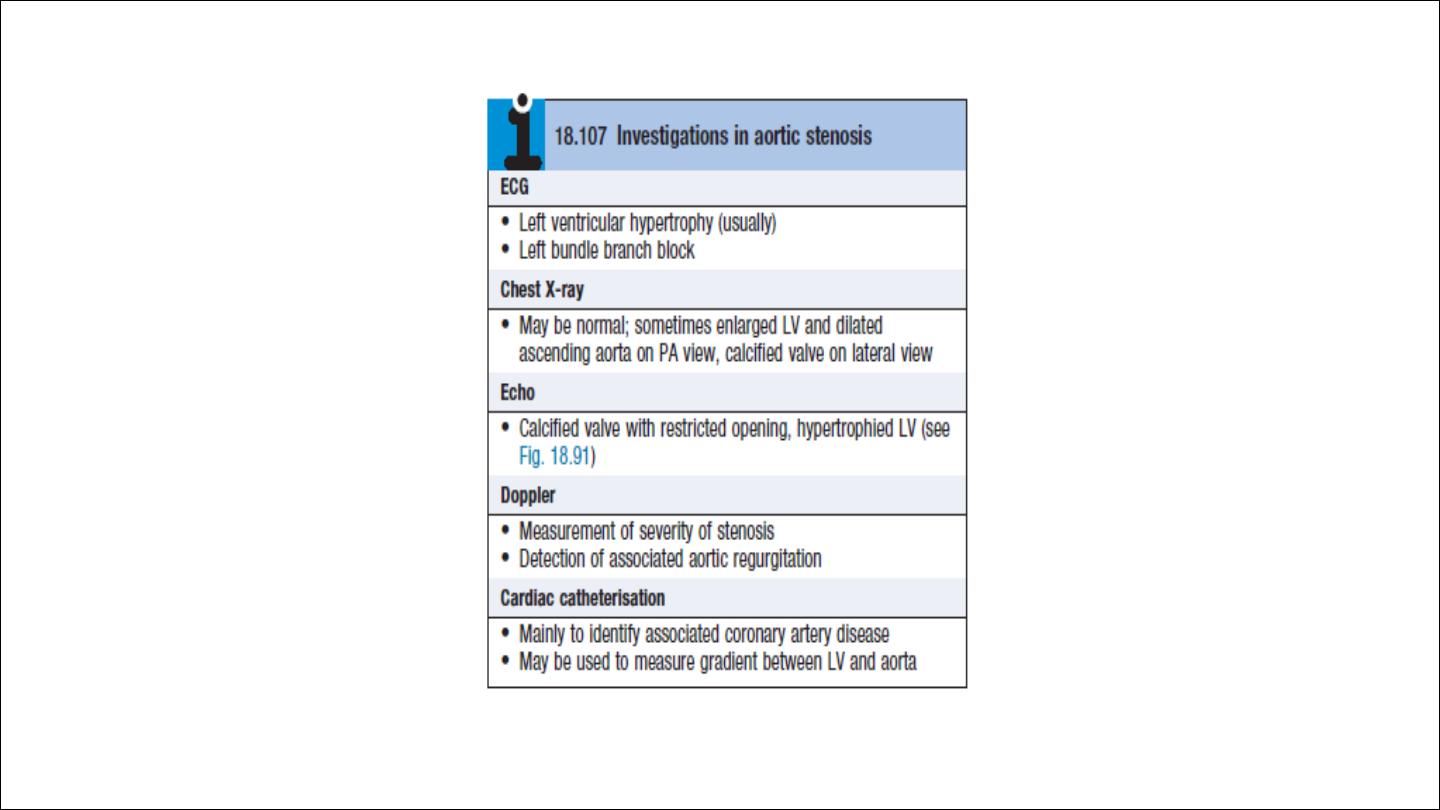

Aortic stenosis

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

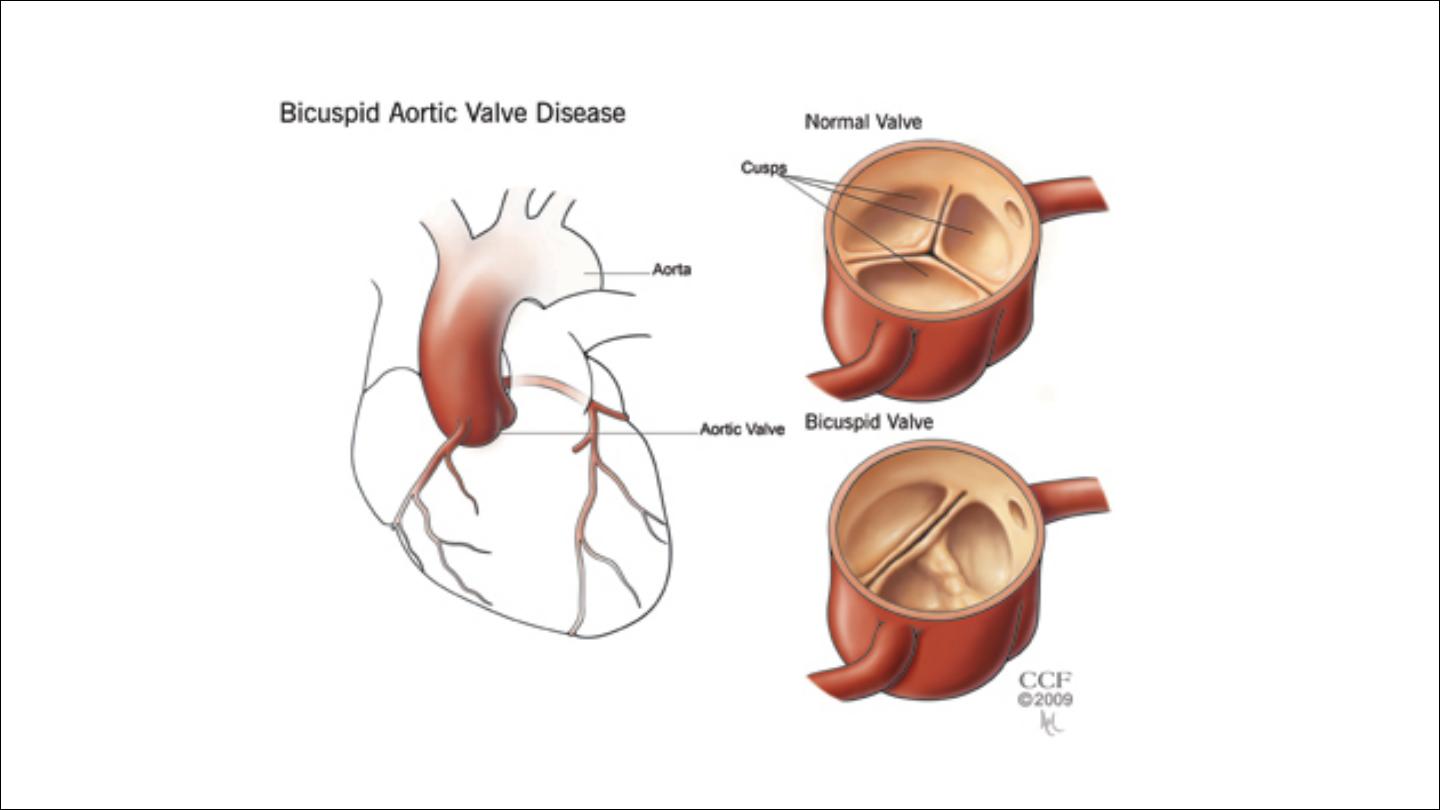

The likely aetiology depends on the age of the patient . In congenital

aortic stenosis, obstruction is present from birth or becomes apparent

in infancy. With bicuspid aortic valves, obstruction may take years to

develop as the valve becomes fibrotic and calcified.

The aortic valve is the second most frequently affected by rheumatic

fever and, commonly, both the aortic and mitral valves are involved. In

older people, a structurally normal tricuspid aortic valve may be

affected by fibrosis and calcification, in a process that is histologically

similar to that of atherosclerosis affecting the arterial wall.

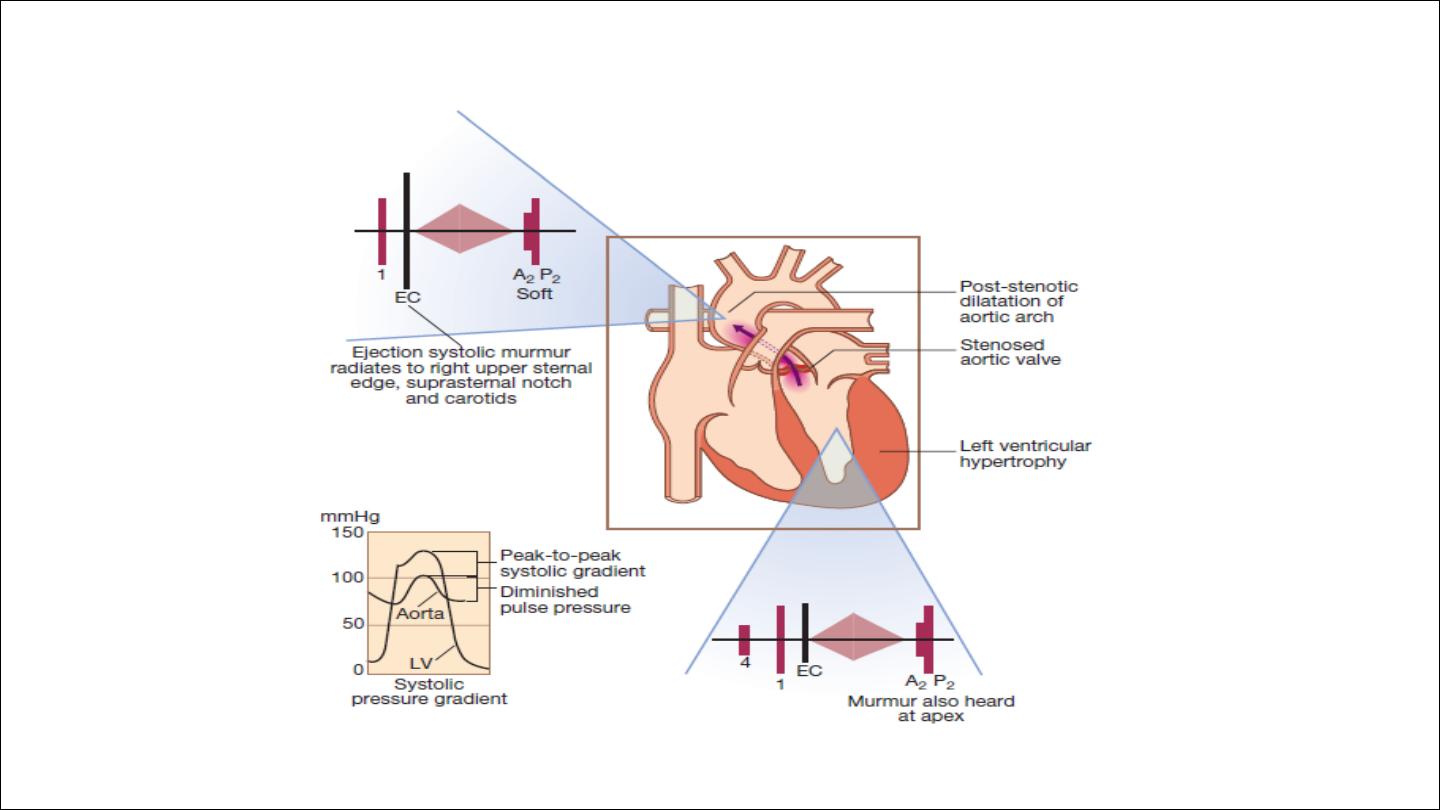

Cardiac output is initially maintained at the cost of a steadily increasing

pressure gradient across the aortic valve. The LV becomes increasingly

hypertrophied and coronary blood flow may then be inadequate.

patients may therefore develop angina, even in the absence of

concomitant coronary disease. The fixed outflow obstruction limits the

increase in cardiac output required on exercise.

Eventually, the LV can no longer overcome the outflow tract

obstruction and pulmonary oedema supervenes.

Haemodynamically significant stenosis develops slowly, typically

occurring at 30–60 years in those with rheumatic disease, 50–60 in

those with bicuspid aortic valves and 70–90 in those with degenerative

calcific disease.

In contrast to patients with mitral stenosis, which tends to progress

very slowly, those with aortic stenosis typically remain asymptomatic

for many years but deteriorate rapidly when symptoms develop, and

death usually ensues within 3–5 years of these.

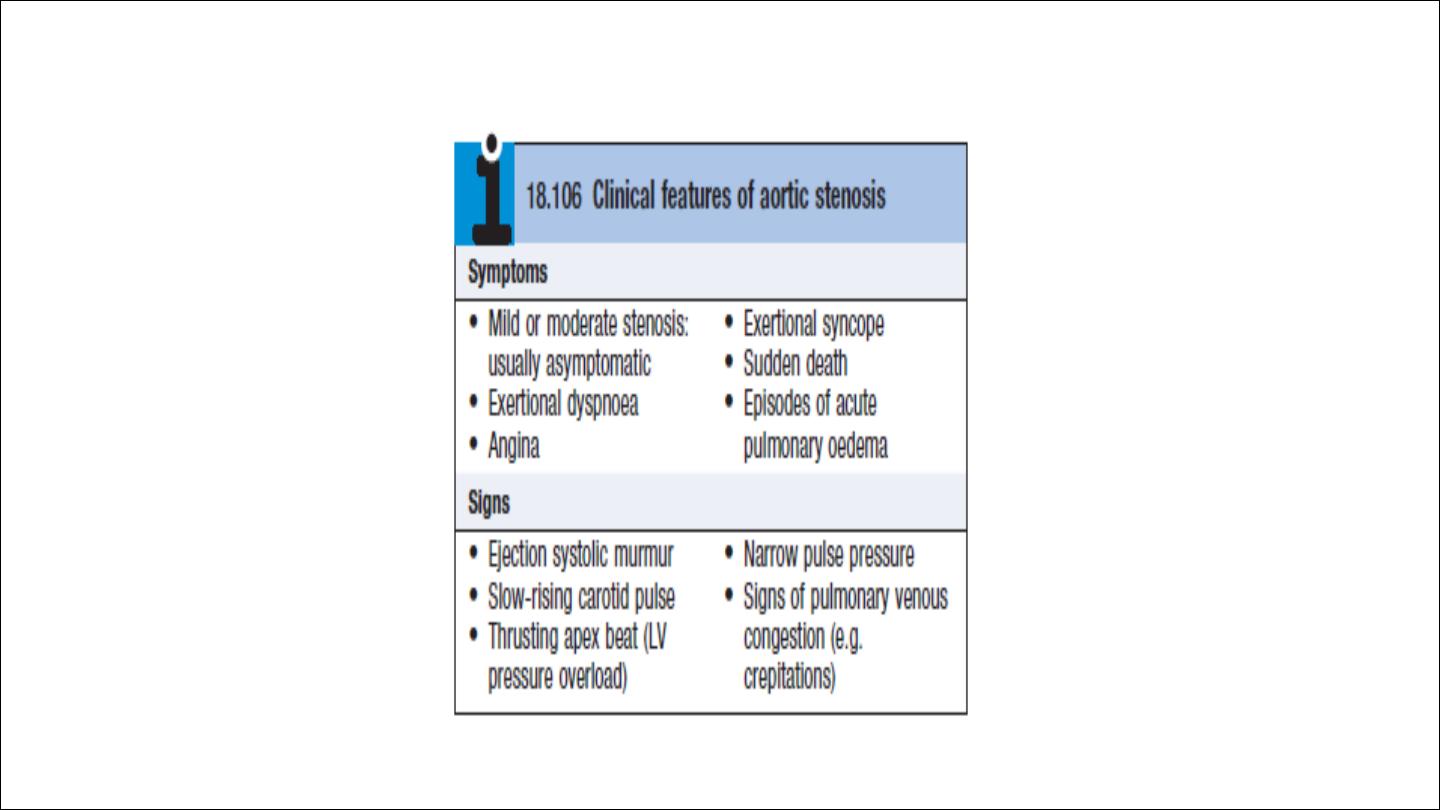

Clinical features

Mild and moderate are usually asymptomatic

Sever can be asymptomatic or symptomatic

Symptoms include

Angina : oxygen mismatch or coexistent CAD (50 %)

exertional Syncope: inability of CO to increase in the presence of fixed

LVOT obstruction

Pulse in AS in elderly can be normal because of stiff non compliant

arteries.

The murmur is often likened to a saw cutting wood and may (especially

in older patients) have a musical quality like the ‘mew’ of a seagull.

Clinical signs of severity

Loud murmur, thrill , soft A2, S4, heaving apex beat

Management

Mild and moderate → asymptomatic

Sever if asymptomatic need only follow up every 1 year, consider

exercise testing

Symptomatic, death occur within 2 to 3 years so its an indication to

surgery.

Age is not a contraindication to valve replacement and results are very

good in experienced centers, even for those in their eighties.

Aortic balloon valvuloplasty is useful in congenital aortic stenosis but is

of no value in older patients with calcific aortic stenosis.

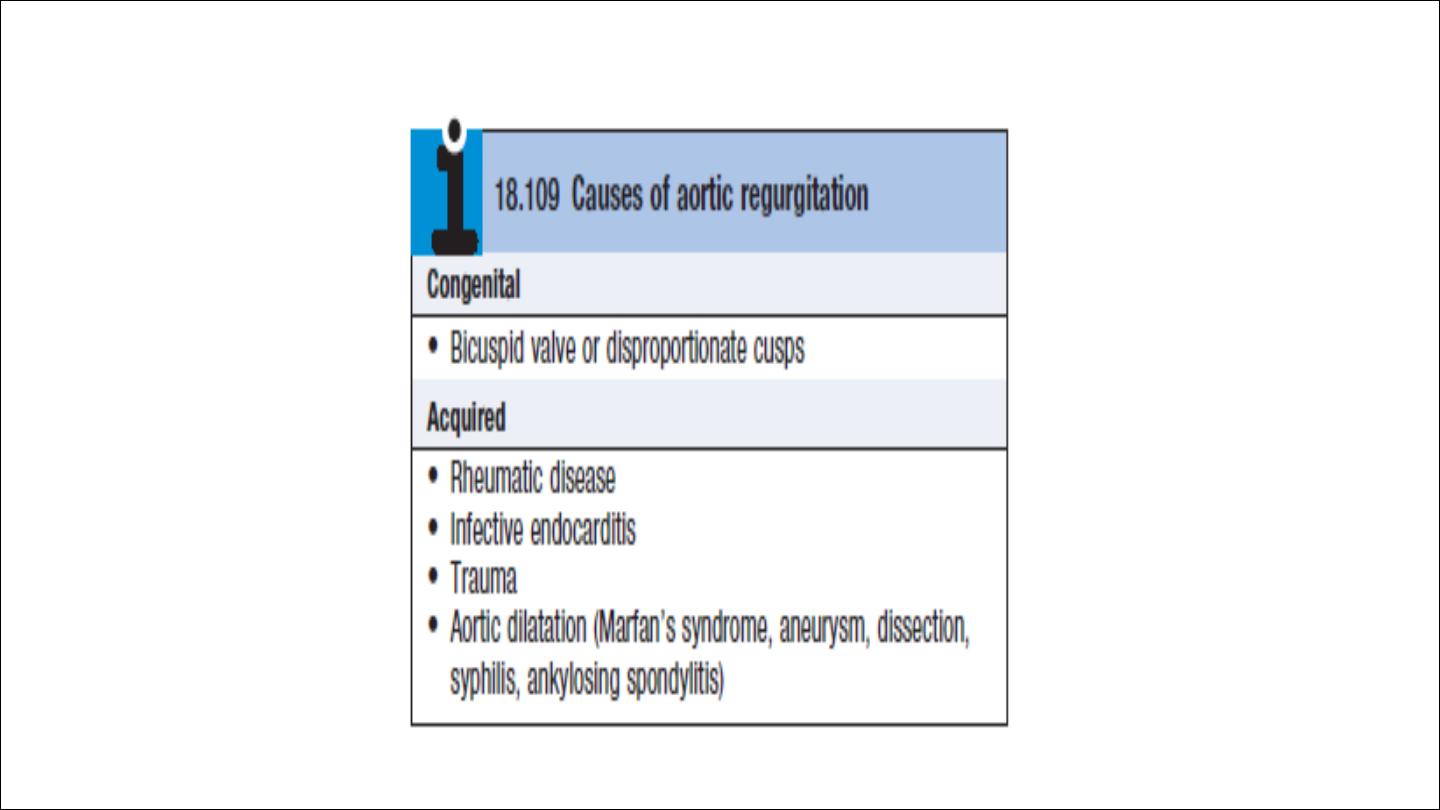

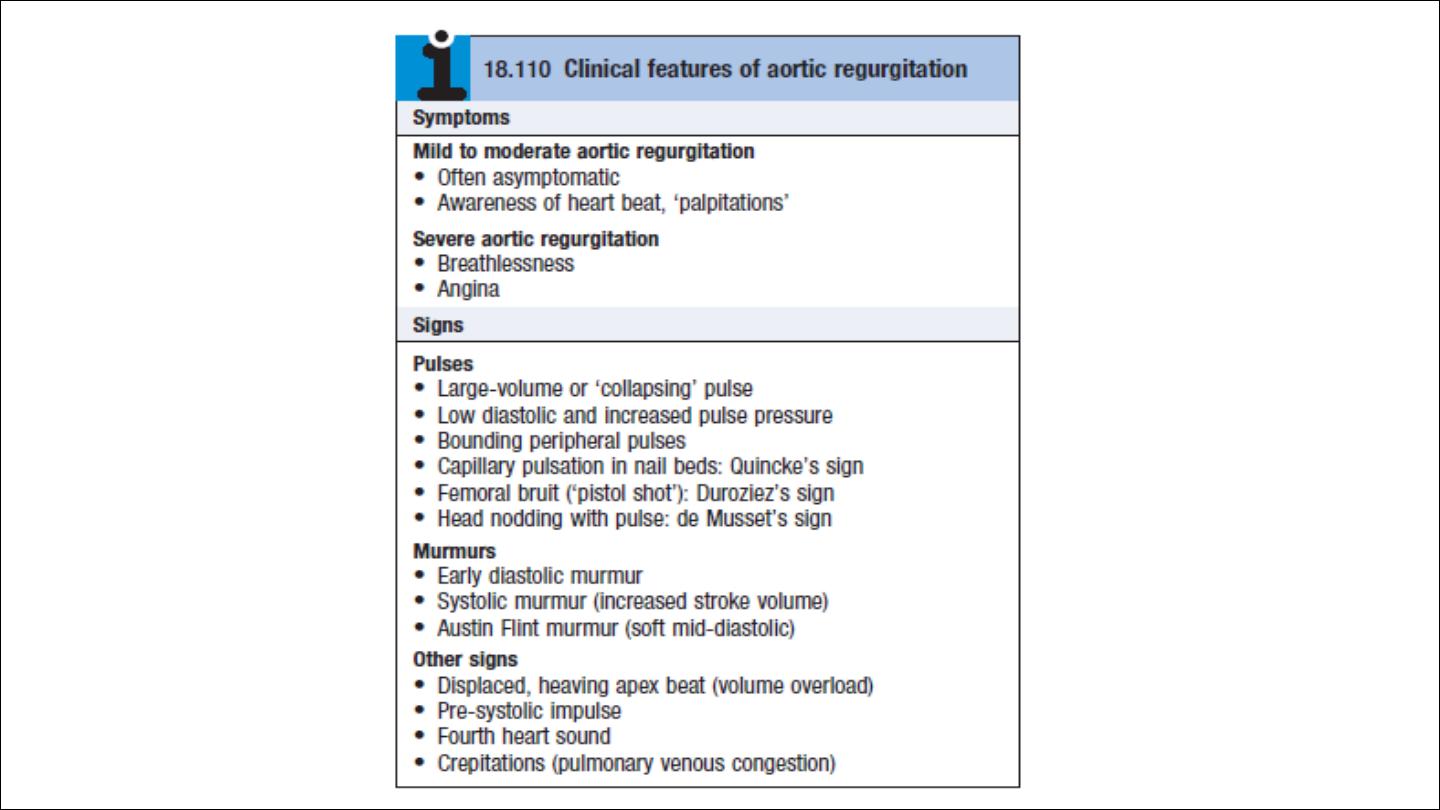

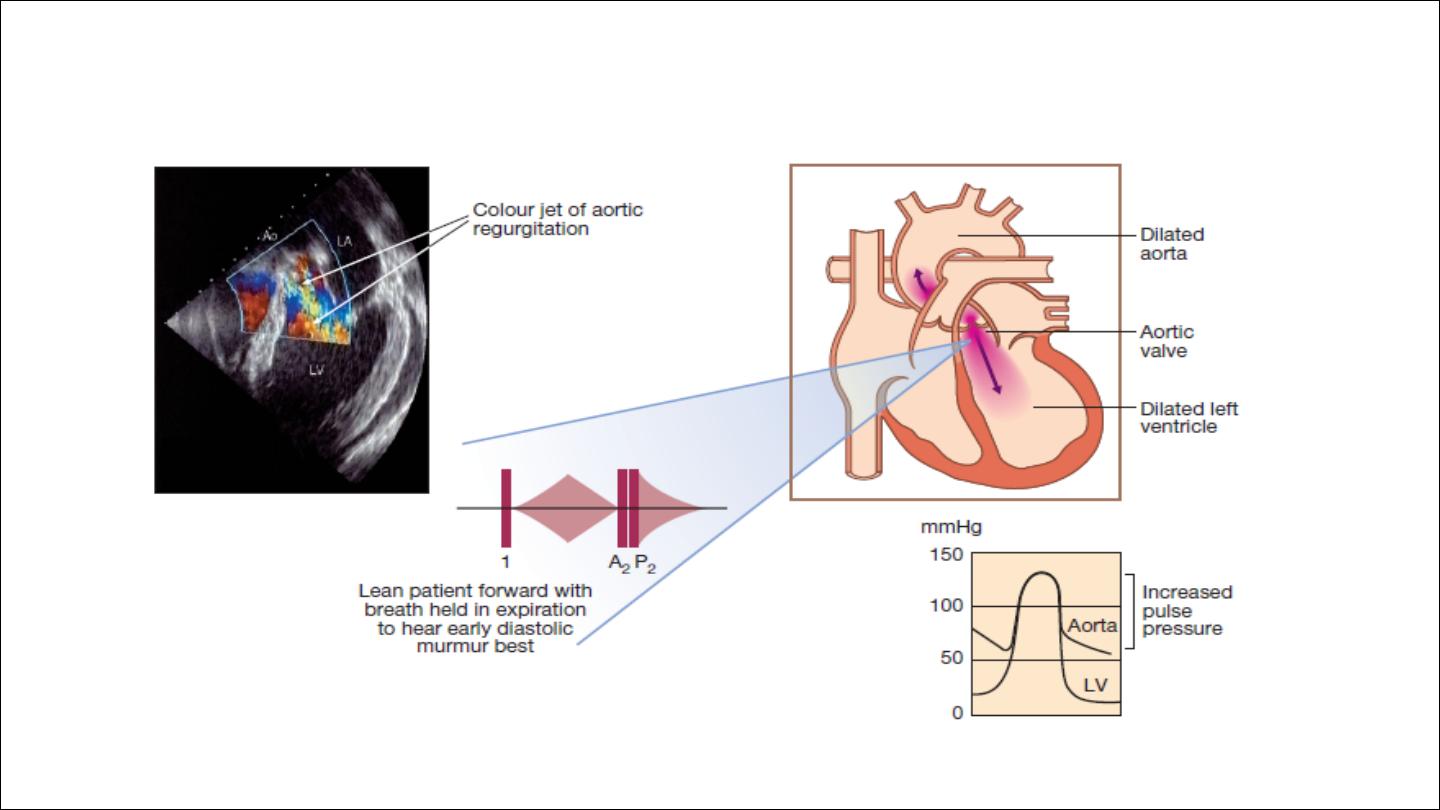

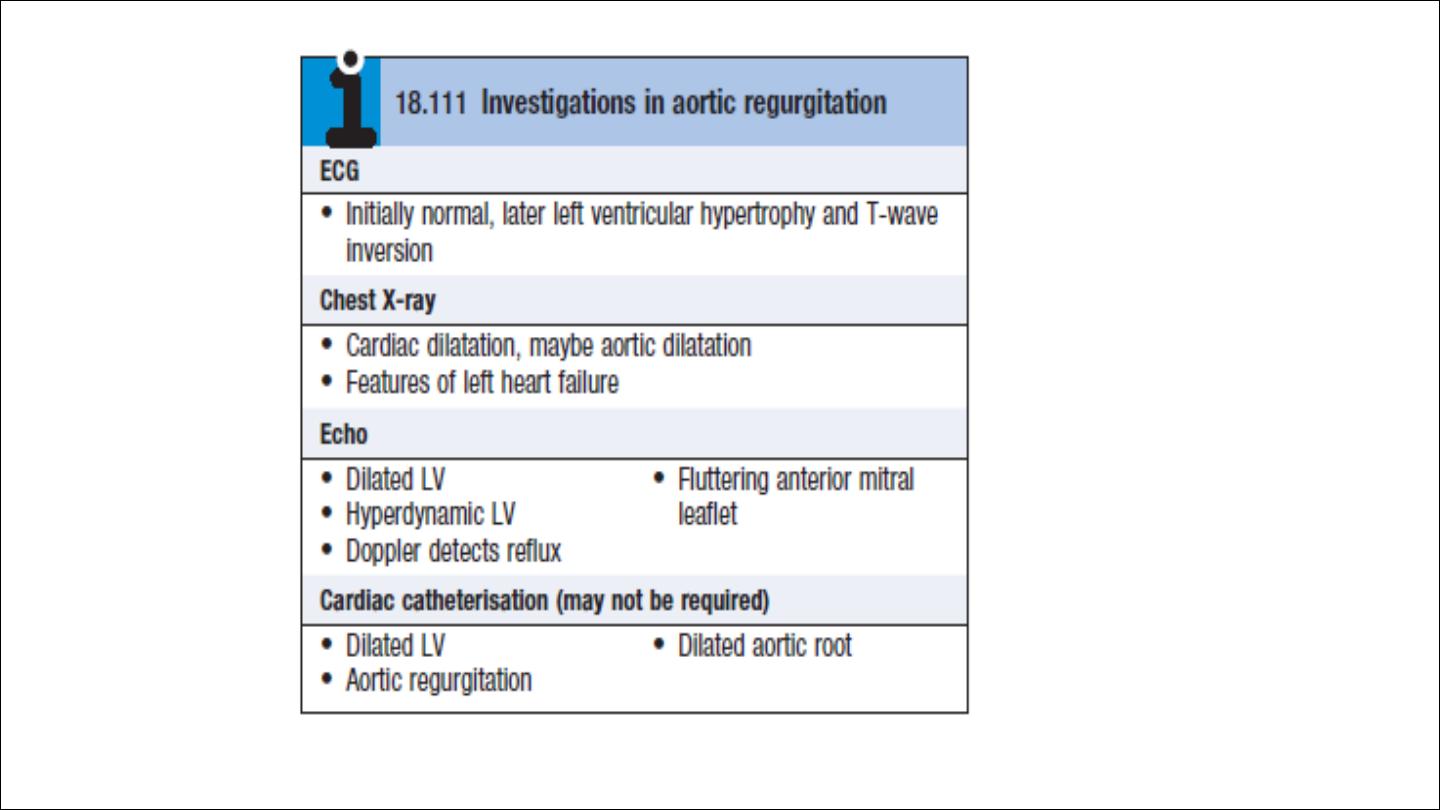

Aortic regurgitation

Aetiology and pathophysiology

This condition is due to disease of the aortic valve cusps

or dilatation of the aortic root.

The LV dilates and hypertrophies to compensate for the

regurgitation.

The stroke volume of the LV may eventually be doubled or

trebled, and the major arteries are then conspicuously

pulsatile.

As the disease progresses, left ventricular diastolic

pressure rises and breathlessness develops.

The regurgitant jet causes fluttering of the mitral valve and, if

severe, causes partial closure of the anterior mitral leaflet,

leading to functional mitral stenosis and a soft mid-diastolic

(Austin Flint) murmur.

In acute severe regurgitation (e.g. perforation of aortic cusp in

endocarditis), there may be no time for compensatory left

ventricular hypertrophy and dilatation to develop and the

features of heart failure may predominate. In this situation,

the classical signs of aortic regurgitation may be masked by

tachycardia and an abrupt rise in left ventricular end-diastolic

pressure thus, the pulse pressure may be near normal and the

diastolic murmur may be short or even absent.

Management

Mild and moderate AR → asymptomatic → follow up

Severe asymptomatic → follow up

Severe symptomatic → AVR

AVR IN ASYMPTOMATIC PATIENTS

1. EF LESS THAN 50 %

2. LVESD MORE THAN 55 MM

3. LVEDD MORE THAN 65 MM

Tricuspid stenosis

Usually rheumatic in origin

Almost always associated with aortic and mitral valve disease

Clinical feature

Symptoms of right sided heart failure

Prominent a wave, slow y descent

Mid diastolic murmur higher pitch than MS, increase with inspiration.

Presystolic hepatic pulsation

Mangement

Surgery

Balloon valvoplasty

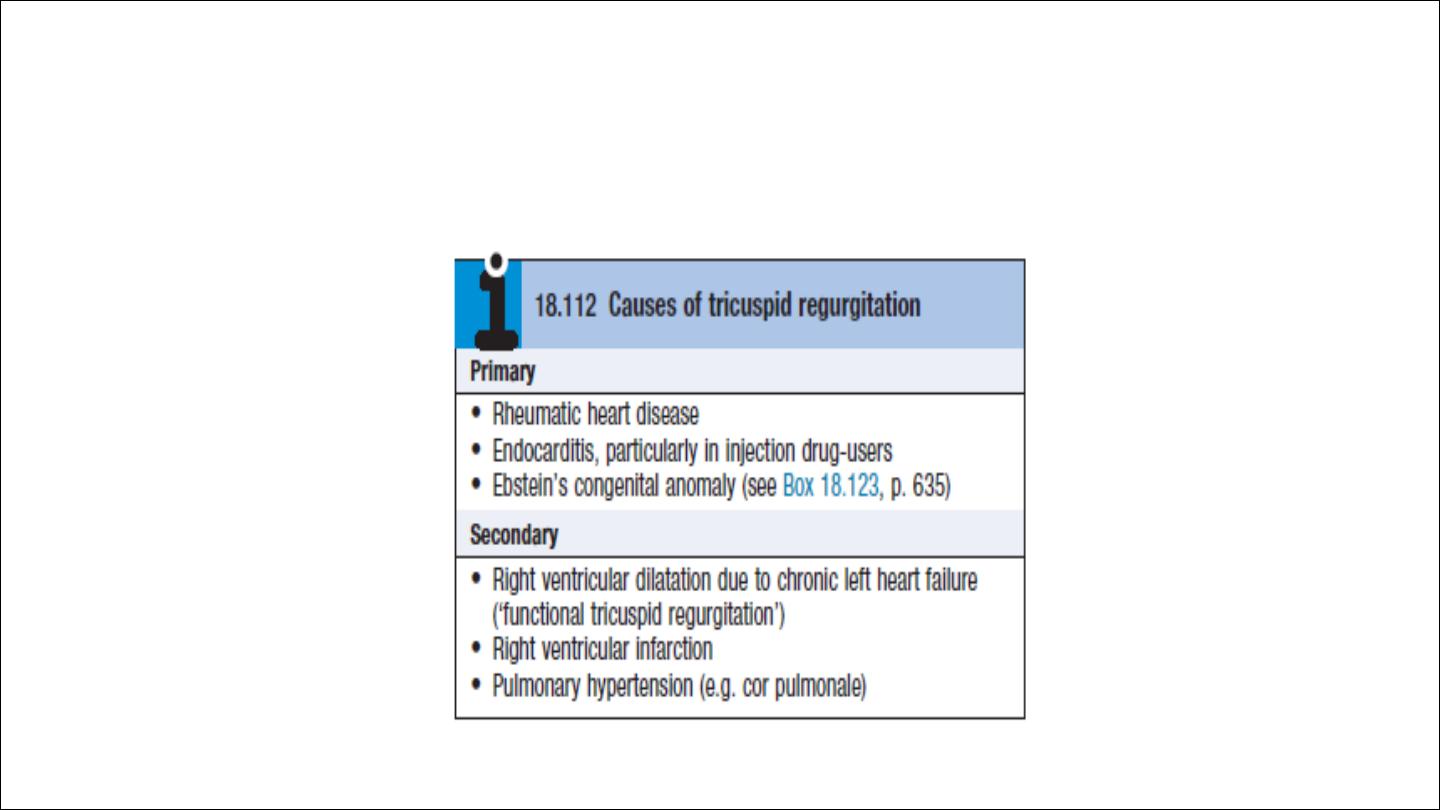

Tricuspid regurgitation

Tricuspid regurgitation is common, and is most frequently ‘functional’

as a result of right ventricular dilatation.

Management

•

Tricuspid regurgitation due to right ventricular dilatation often

improves when the cardiac failure is treated. Patients with a

normal pulmonary artery pressure tolerate isolated tricuspid reflux

well, and valves damaged by endocarditis do not usually need to

be replaced.

•

Patients undergoing mitral valve replacement, who have tricuspid

regurgitation due to marked dilatation of the tricuspid annulus,

benefit from valve repair with an annuloplasty ring to bring the

leaflets closer together. Those with rheumatic damage may require

tricuspid valve replacent

Pulmonary stenosis

Usually congenital, or associated with carcinoid syndrome

Clinical features:

Ejection systolic murmur, loudest at the left upper sternum and radiating

towards the left shoulder. There may be a thrill, best felt when the patient leans

forward and breathes out. The murmur is often preceded by an ejection sound

(click).

Management:

Mild to moderate PS need no treatment. Severe pulmonary stenosis (resting

gradient > 50 mmHg with a normal cardiac output) is treated by percutaneous

pulmonary balloon valvuloplasty or, if this is not available, by surgical

valvotomy. Long-term results are very good. Post-operative pulmonary

regurgitation is common but benign.