ATHEROSCLEROSIS

ATHEROSCLEROSIS

Atherosclerosis can affect any artery in the body

Occult coronary artery disease is common in those

who present with other forms of atherosclerotic

vascular disease

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Type I ( initial lesion)

: isolated macrophage ,foam

cells

Type II ( fatty streak)

: intracellular lipid

Type III (intermediate lesion

); type II+ small

extracellular lip[id pool

Type IV (atheroma lesion)

:type II + core of

extracellular lipid pool

Type V (fibroatheroma

): Lipid core + fibrotic layer

Type VI (complicated

): surface defect , hematoma

;hemorrhage ; thrombus

EARLY ATHEROSCLEROSIS

Atherosclerosis begins early in life

Early atherosclerotic lesions have been found in the

arteries of victims of accidental death in the second

and third decades of life

Fatty streaks tend to occur at sites of altered arterial

shear stress

They develop when inflammatory cells, predominantly

monocytes, bind to receptors expressed by

endothelial cells, migrate into the intima, take up

oxidised low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles and

become lipid-laden macrophages or foam cells

ADVANCED

ATHEROSCLEROSIS

In an established atherosclerotic plaque,

macrophages mediate inflammation and smooth

muscle cells promote repair.

Any breach in the integrity of the plaque will

expose its contents to blood, and trigger platelet

aggregation and thrombosis that extend into the

atheromatous plaque and the arterial lumen

'Vulnerable' plaques are characterised by a lipid-rich

core, a thin fibrocellular cap and an increase in

inflammatory cells that release specific enzymes to

degrade matrix proteins. In contrast, stable plaques are

typified by a small lipid pool, a thick fibrous cap,

calcification and plentiful collagenous cross-struts

Atherosclerosis may induce complex changes in the

media that lead to arterial remodelling ( posative and

negative)

RISK FACTORS

Age and sex.

Family history.

Smoking.

Hypertension

Hypercholesterolaemia

Diabetes mellitus.

Haemostatic factors.

Physical activity.

Obesity

Alcohol.

Other dietary factors.

Personality.

Social deprivation.

PREVENTION

Primary prevention

Secondary prevention

CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common form

of heart disease

By 2020, it is estimated that it will be the major

cause of death in all regions of the world.

Occasionally, the coronary arteries are involved in other

disorders such as aortitis, polyarteritis and other

connective tissue disorders.

CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE: CLINICAL

MANIFESTATIONS AND PATHOLOGY

Stable angina Ischaemia due to fixed atheromatous

stenosis of one or more coronary arteries

Unstable angina Ischaemia caused by dynamic

obstruction of a coronary artery due to plaque rupture or

erosion with superimposed thrombosis

Myocardial infarction Myocardial necrosis caused by

acute occlusion of a coronary artery due to plaque rupture

or erosion with superimposed thrombosis

Heart failure Myocardial dysfunction due to infarction or

ischaemia

Arrhythmia Altered conduction due to ischaemia or

infarction

Sudden death Ventricular arrhythmia, asystole or massive

myocardial infarction

STABLE ANGINA

is the symptom complex caused by transient

myocardial ischaemia and constitutes a clinical

syndrome rather than a disease.

imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and

demand

may be a manifestation of other forms of heart

disease, particularly aortic valve disease and

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

FACTORS INFLUENCING MYOCARDIAL OXYGEN SUPPLY AND

DEMAND

Oxygen demand: cardiac work

Heart rate

BP

Myocardial contractility

Left ventricular hypertrophy

Valve disease, e.g. aortic stenosis

Oxygen supply: coronary blood flow

Duration of diastole

Coronary perfusion pressure (aortic diastolic minus coronary sinus or right

atrial diastolic pressure)

Coronary vasomotor tone

Oxygenation

Haemoglobin

Oxygen saturation

ACTIVITIES PRECIPITATING

ANGINA

Common

Physical exertion

Cold exposure

Heavy meals

Intense emotion

Uncommon

Lying flat (decubitus angina)

Vivid dreams (nocturnal angina)

INVESTIGATIONS

Resting ECG

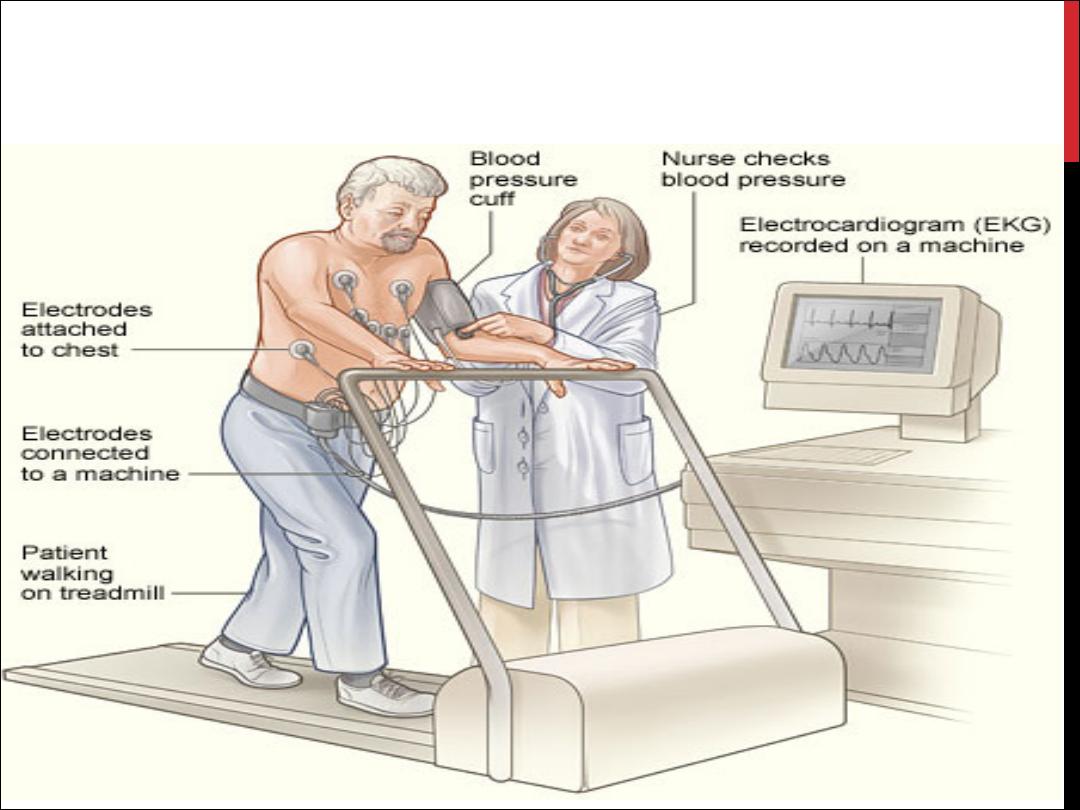

Exercise ECG

EXERCISE ECG

OTHER FORMS OF STRESS

TESTING

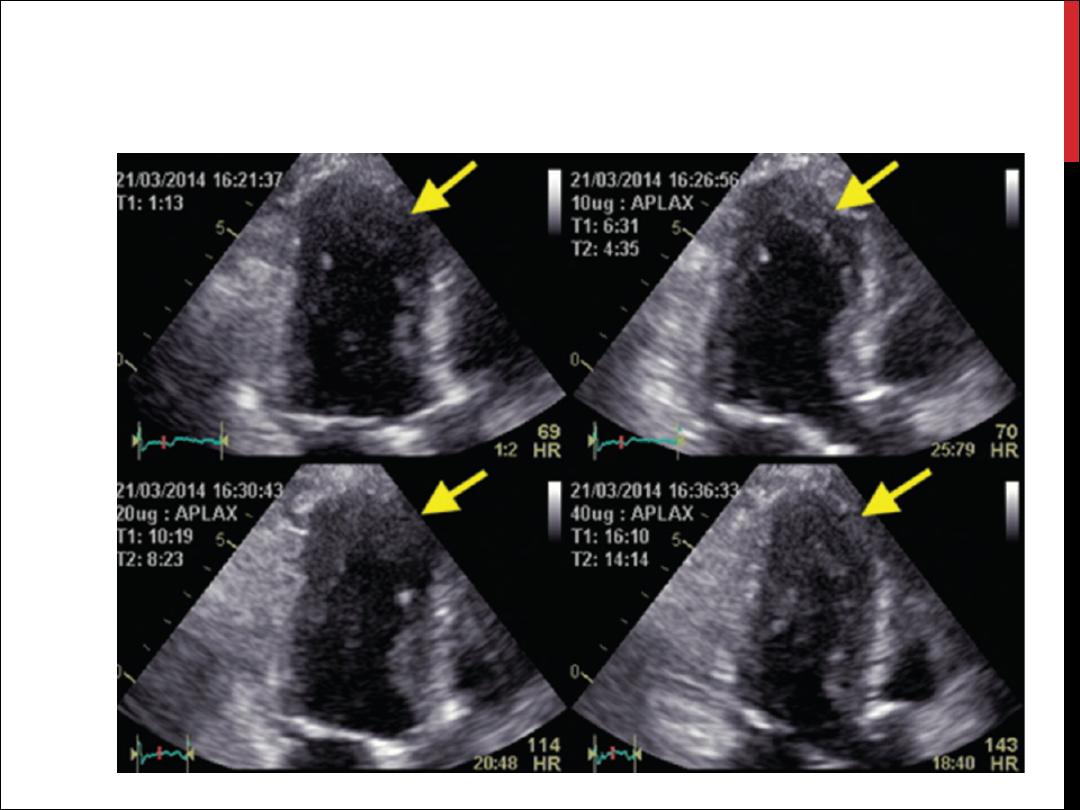

Stress echocardiography

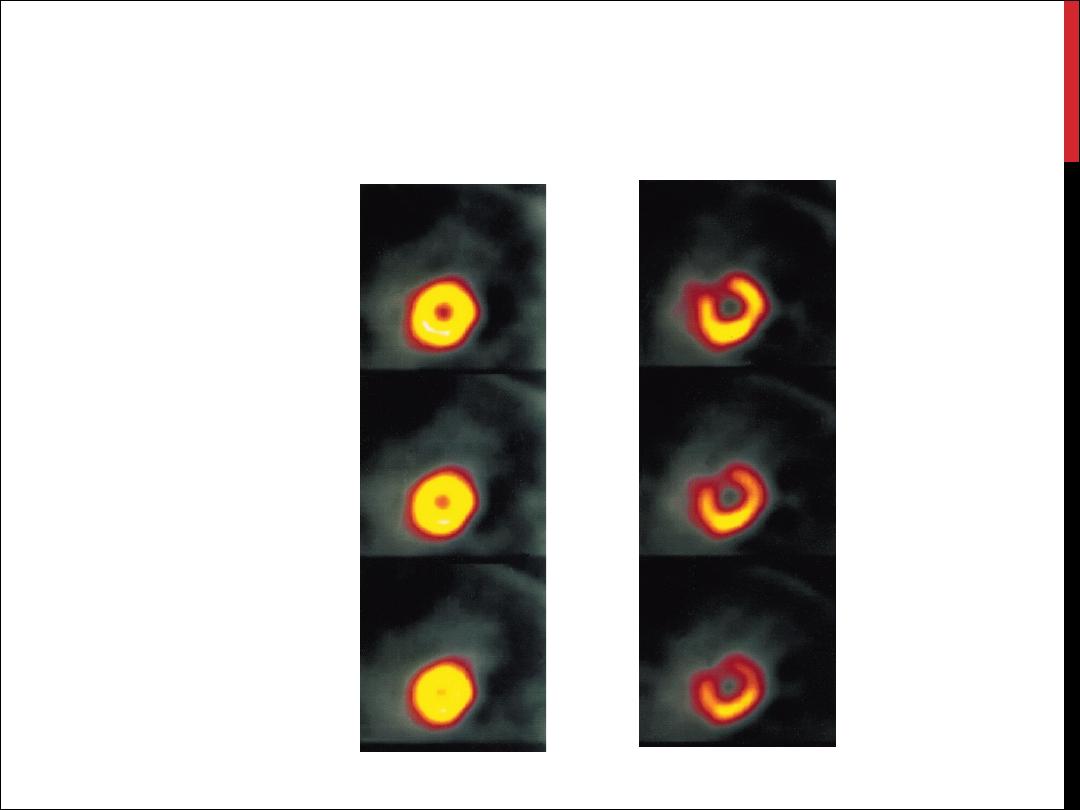

Myocardial perfusion scanning

Coronary arteriography

STRESS ECHO

MYOCARDIAL PERFUSION

SCANNING

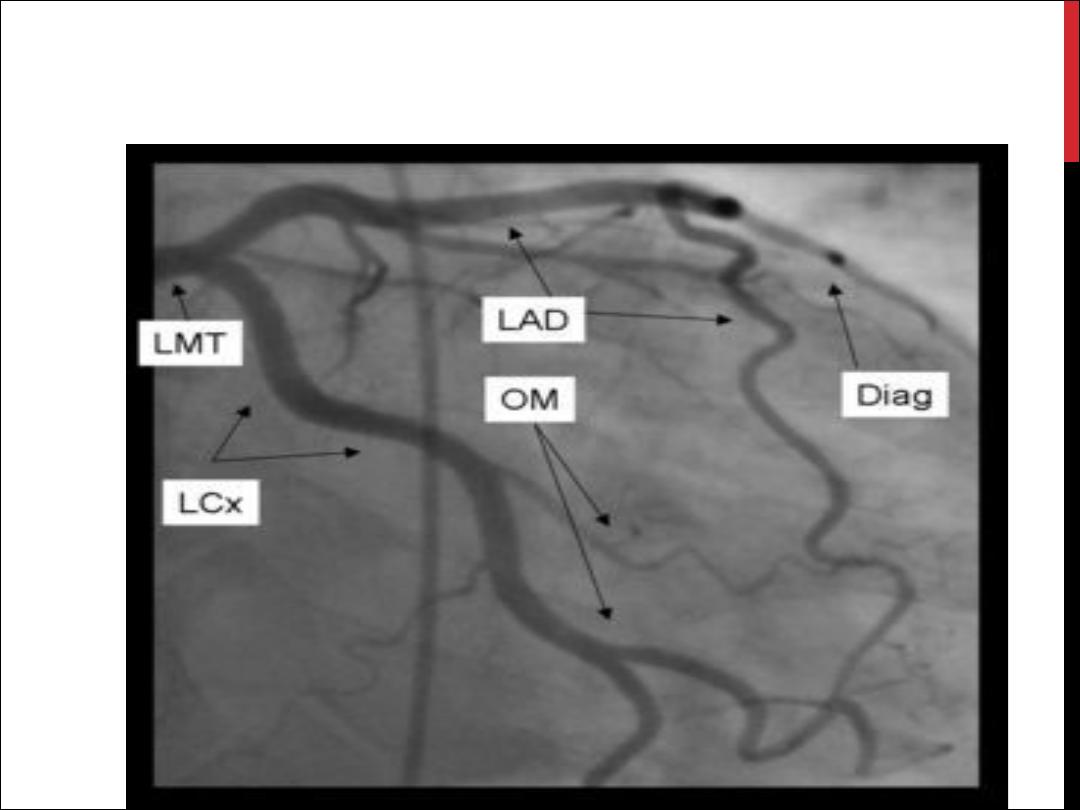

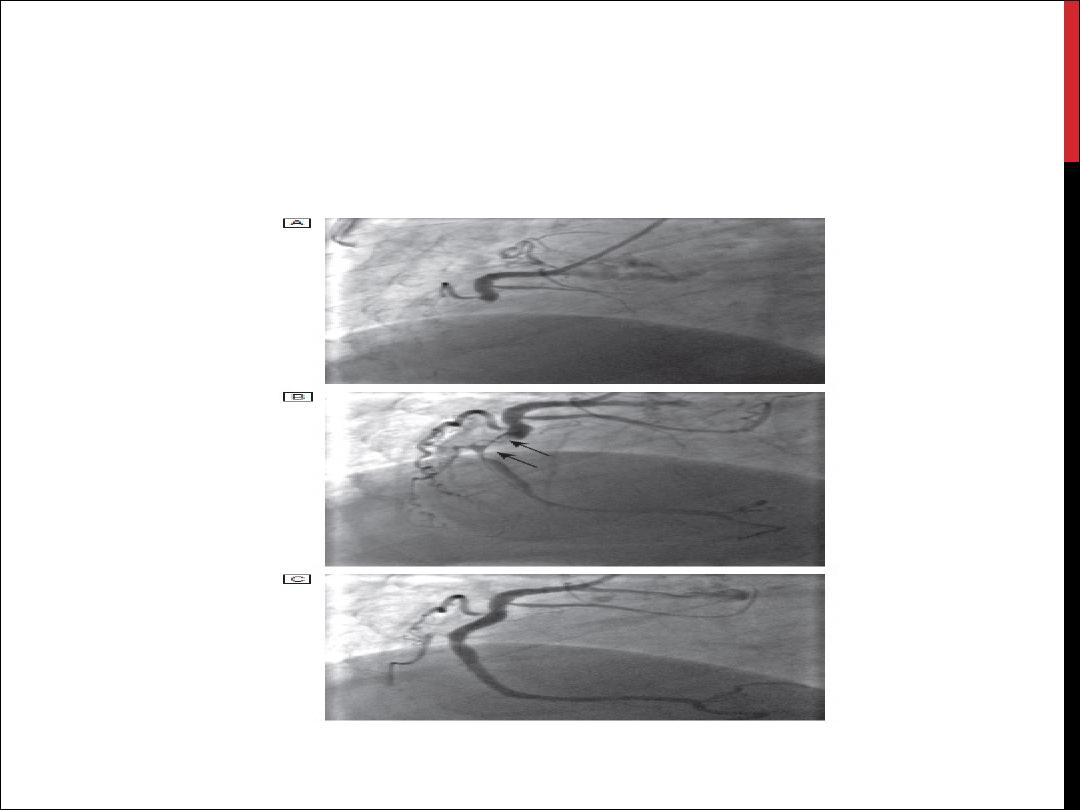

CORONARY ANGIO.

RISK STRATIFICATION IN STABLE ANGINA

High risk

Low risk

Post-infarct angina

Predictable exertional angina

Poor effort tolerance

Good effort tolerance

Ischaemia at low workload

Ischaemia only at high workload

Left main or three-vessel disease

Single-vessel or two-vessel disease

Poor LV function

Good LV function

MANAGEMENT: GENERAL

MEASURES

a careful assessment of the likely extent and

severity of arterial disease

the identification and control of risk factors

such as smoking, hypertension and

hyperlipidaemia

the use of measures to control symptoms

the identification of high-risk patients for

treatment to improve life expectancy.

ADVICE TO PATIENTS WITH STABLE

ANGINA

Ø

Do not smoke

Ø

Aim for ideal body weight

Ø

Take regular exercise (exercise up to, but not

beyond, the point of chest discomfort is beneficial

and may promote collateral vessels)

Ø

Avoid severe unaccustomed exertion, and

vigorous exercise after a heavy meal or in very

cold weather

Ø

Take sublingual nitrate before undertaking

exertion that may induce angina

PHARMACOLOGICAL THERAPY

Antiplatelet therapy

Anti-anginal drug treatment

Nitrates

Beta-blockers

Calcium channel antagonists

Potassium channel activators

I

f

channel antagonist

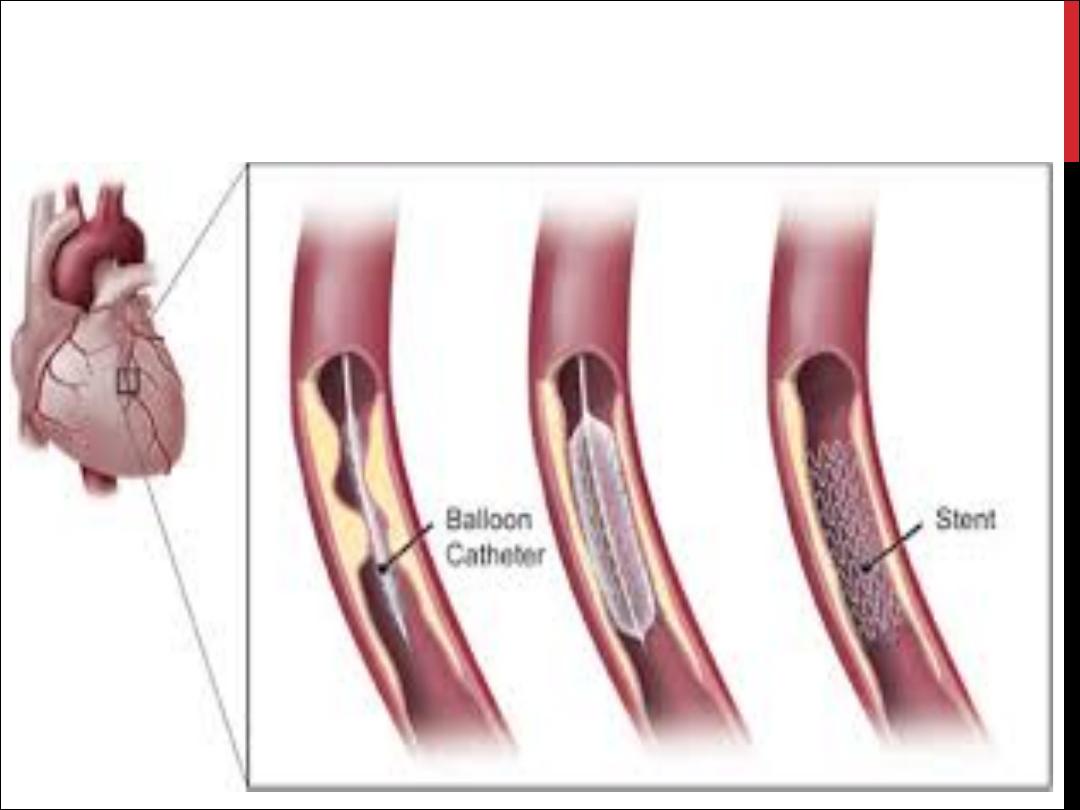

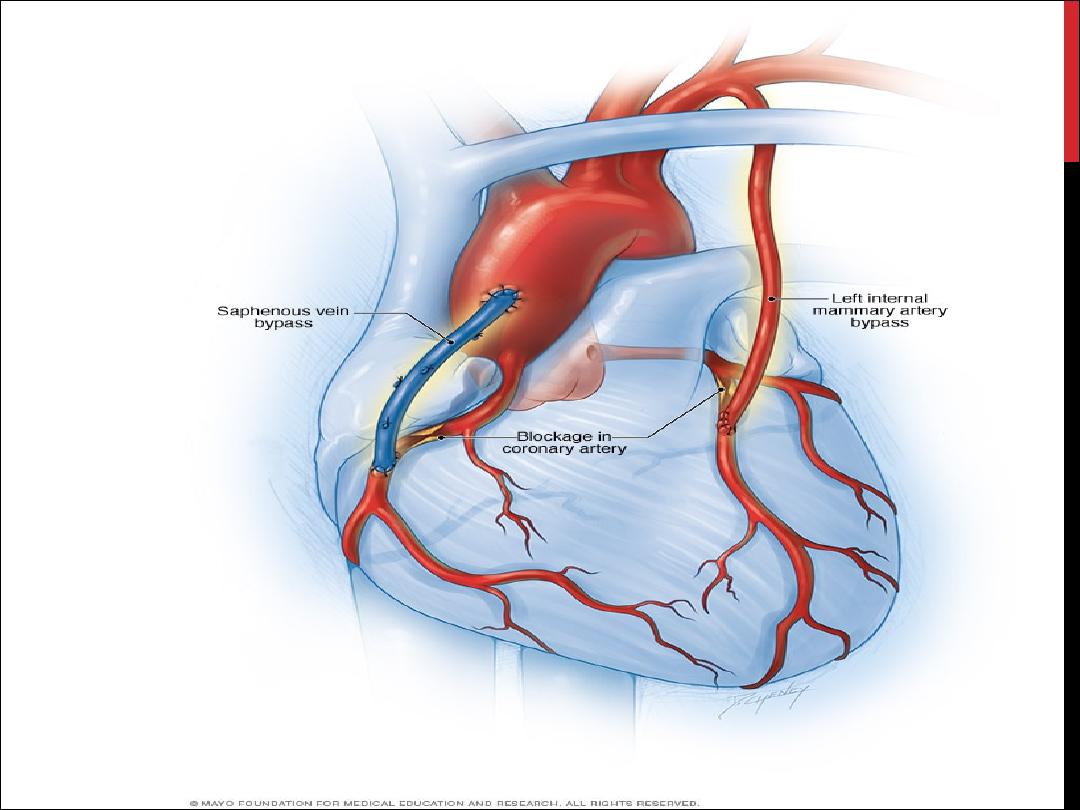

INVASIVE THERAPY : PCI AND CABG

COMPARISON OF PCI AND CABG

PCI

CABG

Death

>

0.5

%

>

1.5

%

Myocardial infarction*

2

%

10

%

Hospital stay

12-36 hrs

5-8 days

Return to work

2-5 days

6-12 wks

Recurrent angina

15-20% at 6 mths

10% at 1 yr

Repeat revascularisation

10-20% at 2 yrs

2% at 2 yrs

Neurological complications Rare

Common (see text)

Other complications

Emergency CABG

Vascular damage related to

access site

Diffuse myocardial damage

Infection (chest, wound)

Wound pain

PROGNOSIS

Symptoms are a poor guide to prognosis

Exercise testing and other forms of stress testing

are much more powerful predictors of mortality

In general, the prognosis of coronary artery

disease is related to the number of diseased

vessels and the degree of left ventricular

dysfunction.

ANGINA WITH NORMAL CORONARY

ARTERIES

Coronary artery spasm

Syndrome X

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME

Unstable Angina

MI

The culprit lesion is usually a complex ulcerated or

fissured atheromatous plaque with adherent platelet-rich

thrombus and local coronary artery spasm

CLINICAL FEATURES

Symptoms

Prolonged cardiac pain: chest, throat, arms, epigastrium or back

Anxiety and fear of impending death

Nausea and vomiting

Breathlessness

Collapse/syncope

Physical signs

Signs of sympathetic activation: pallor, sweating, tachycardia

Signs of vagal activation: vomiting, bradycardia

Signs of impaired myocardial function

•

Hypotension, oliguria, cold peripheries

•

Narrow pulse pressure

•

Raised JVP

•

Third heart sound

•

Quiet first heart sound

•

Diffuse apical impulse

•

Lung crepitations

Signs of tissue damage: fever

Signs of complications: e.g. mitral regurgitation, pericarditis

DIAGNOSIS AND RISK

STRATIFICATION

The differential diagnosis is wide

The assessment of acute chest pain depends heavily on an

analysis of the character of the pain and its associated

features

ECG and Biochemical markers

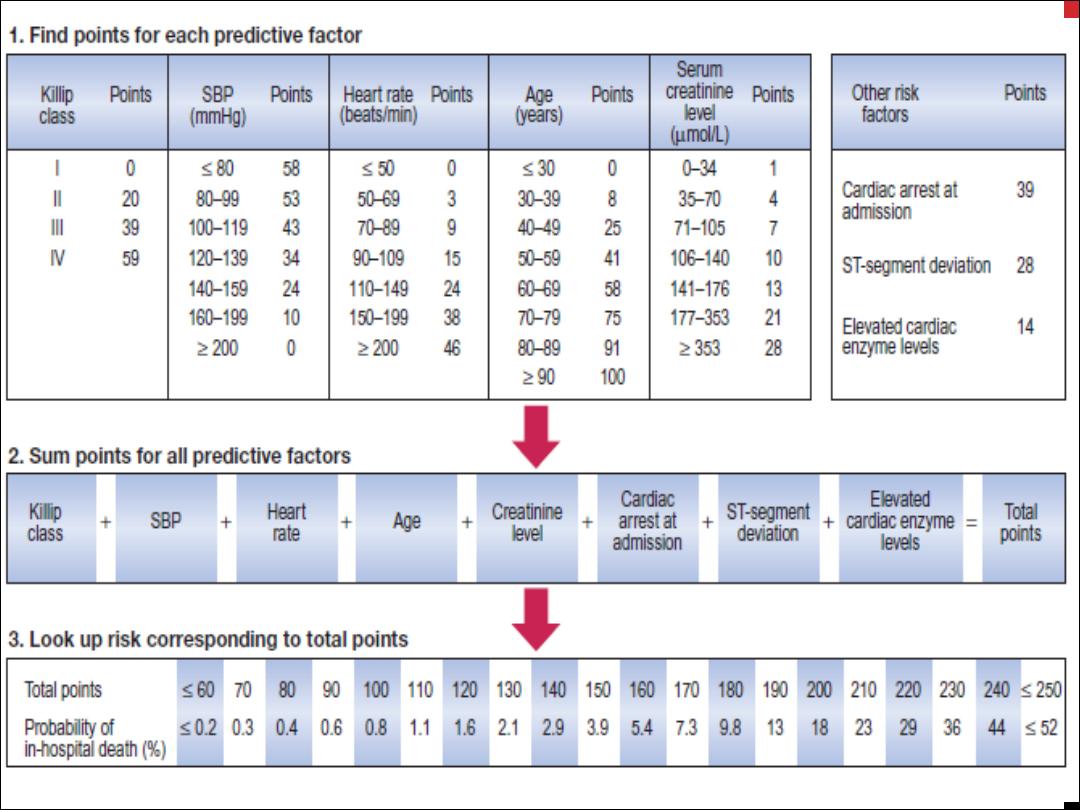

Risk stratification is important because it guides the use of

more complex pharmacological and interventional

treatment (

GRACE

)

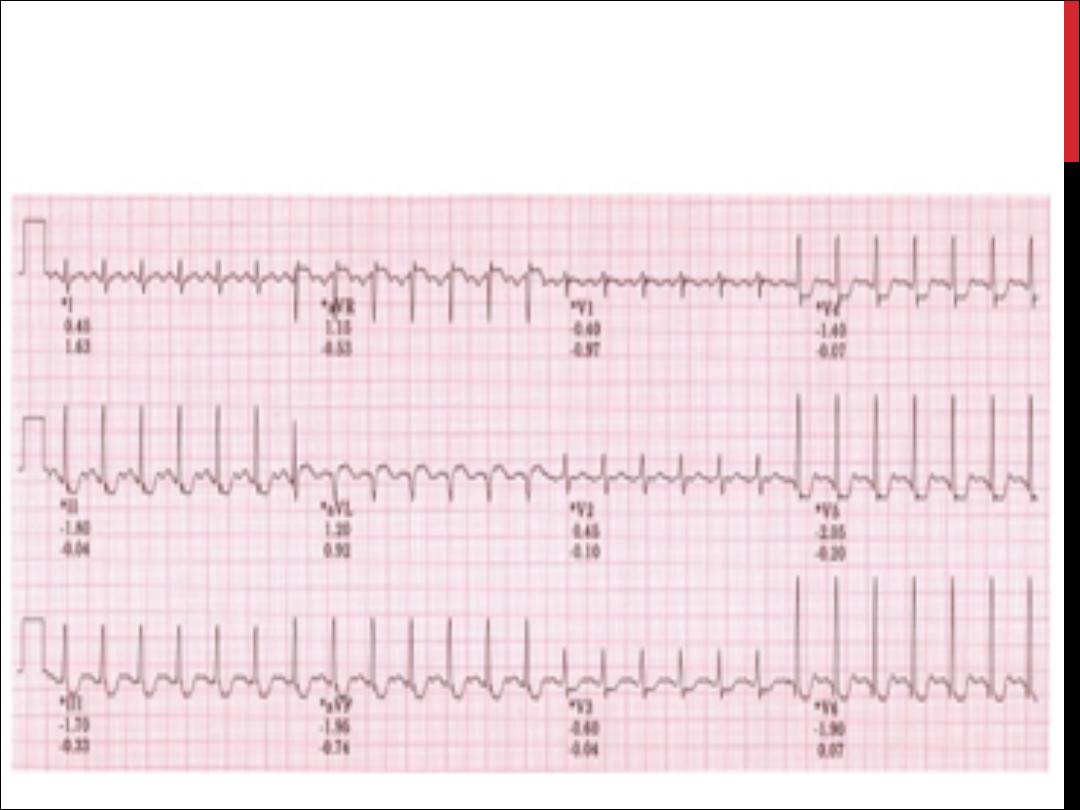

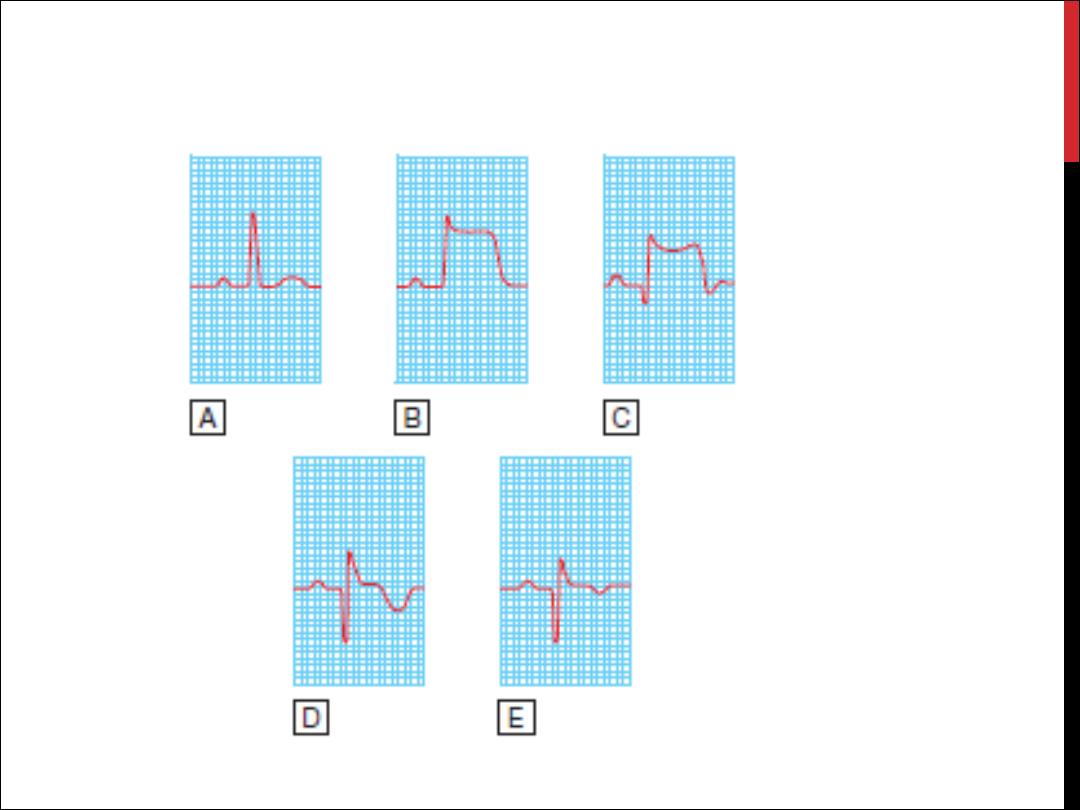

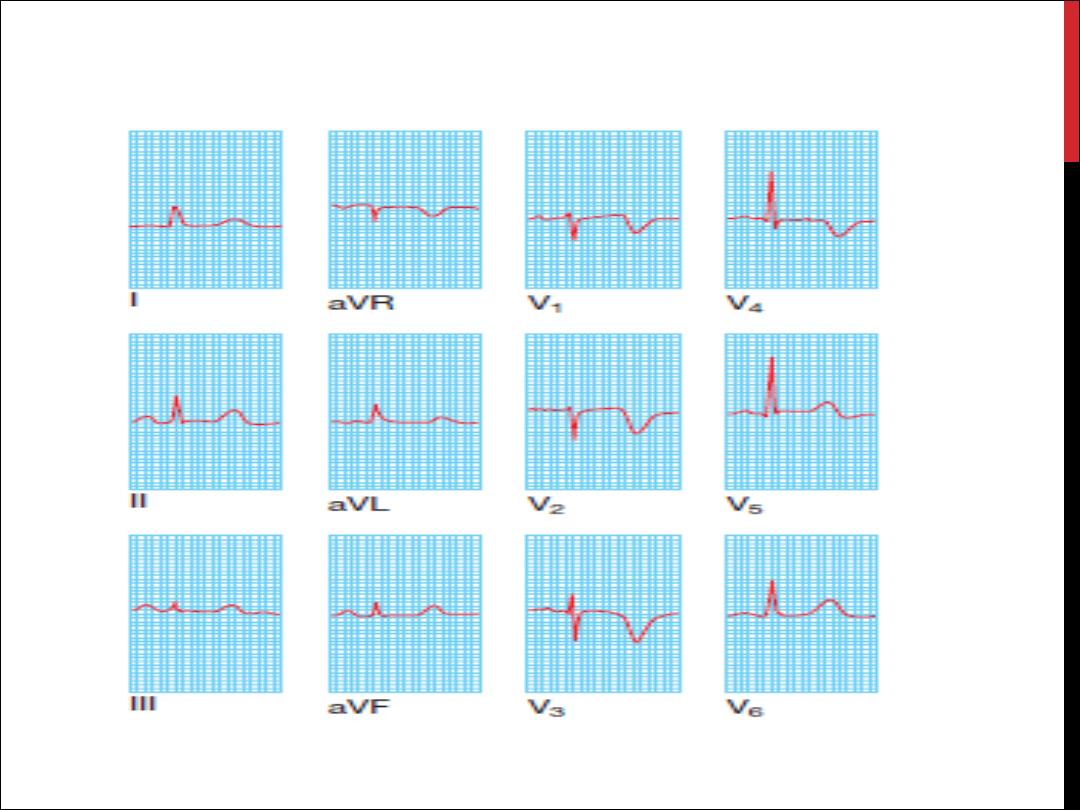

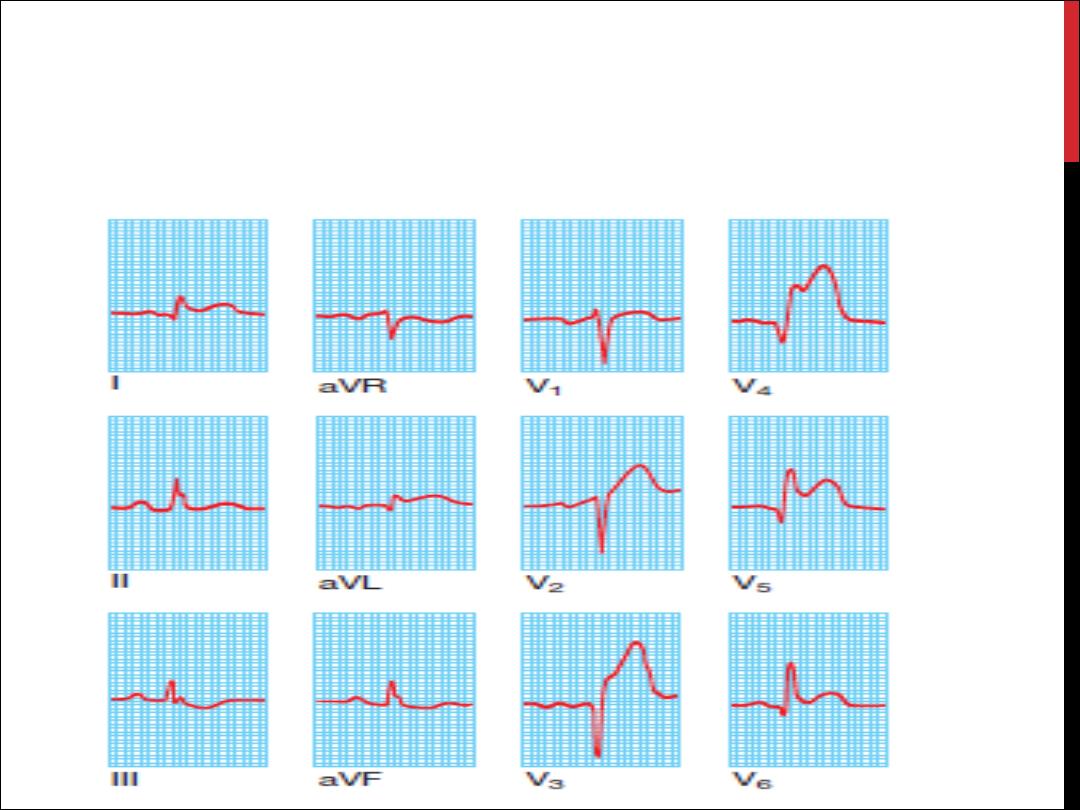

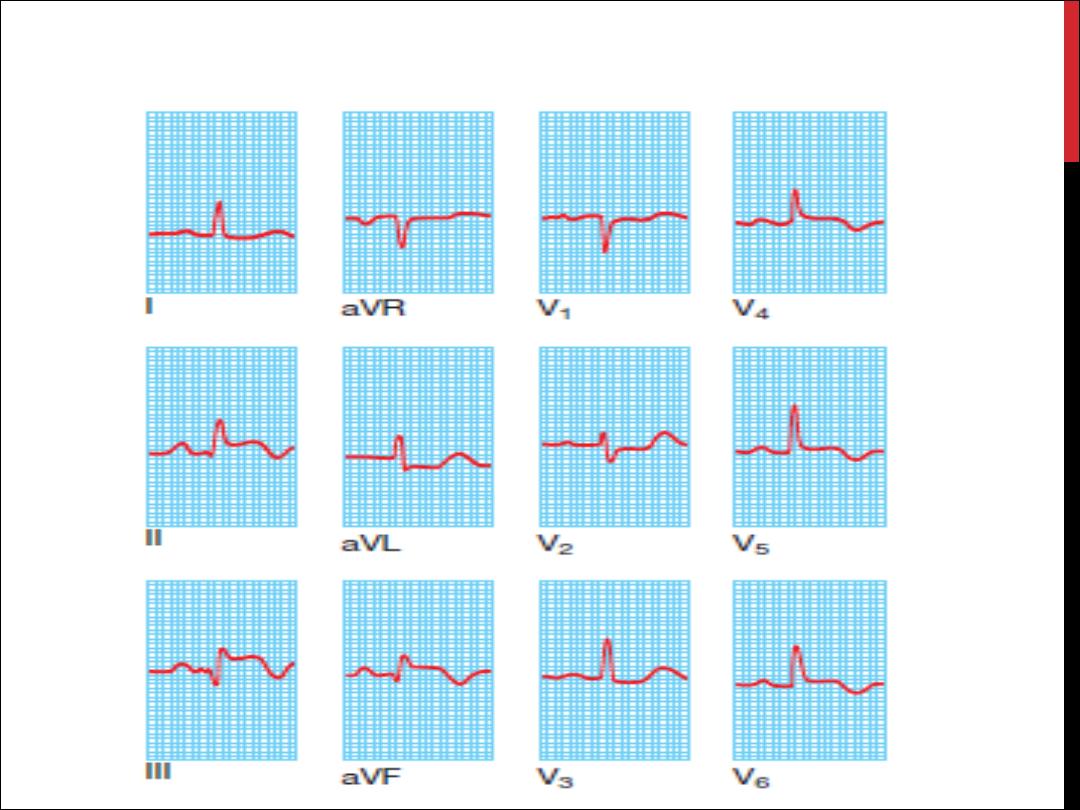

INVESTIGATIONS : ECG

NON STEMI

ANTERIOR STEMI

INFEROLATERAL STEMI

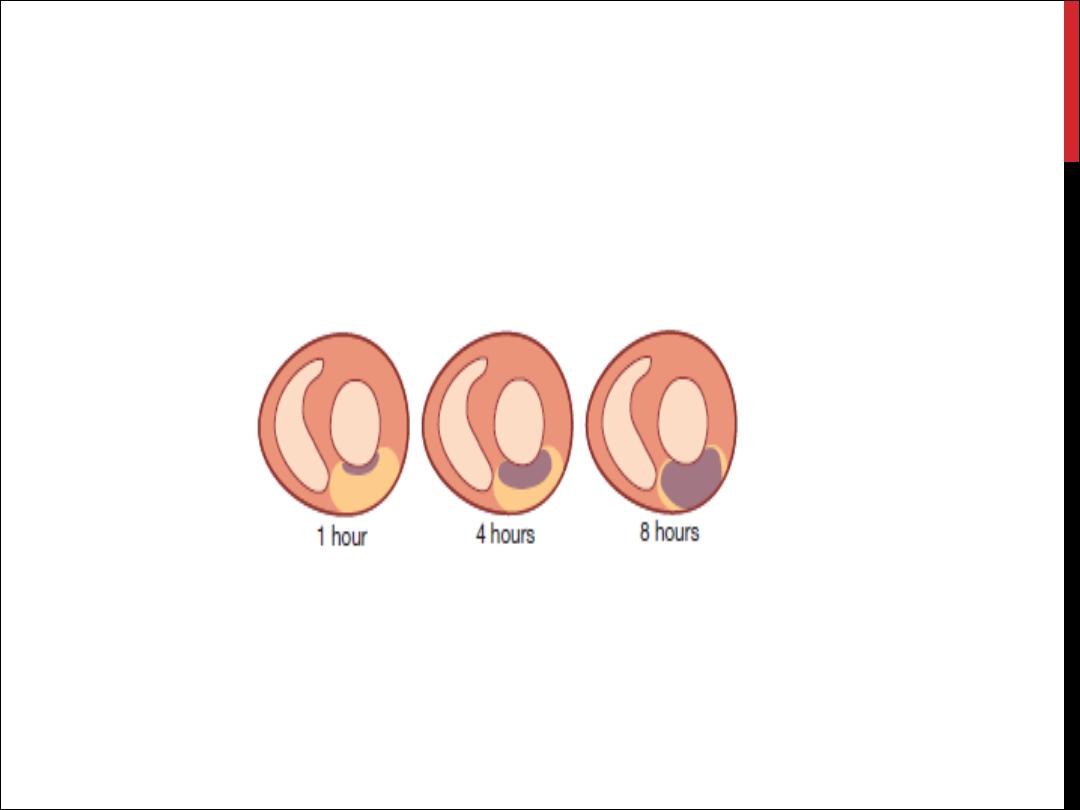

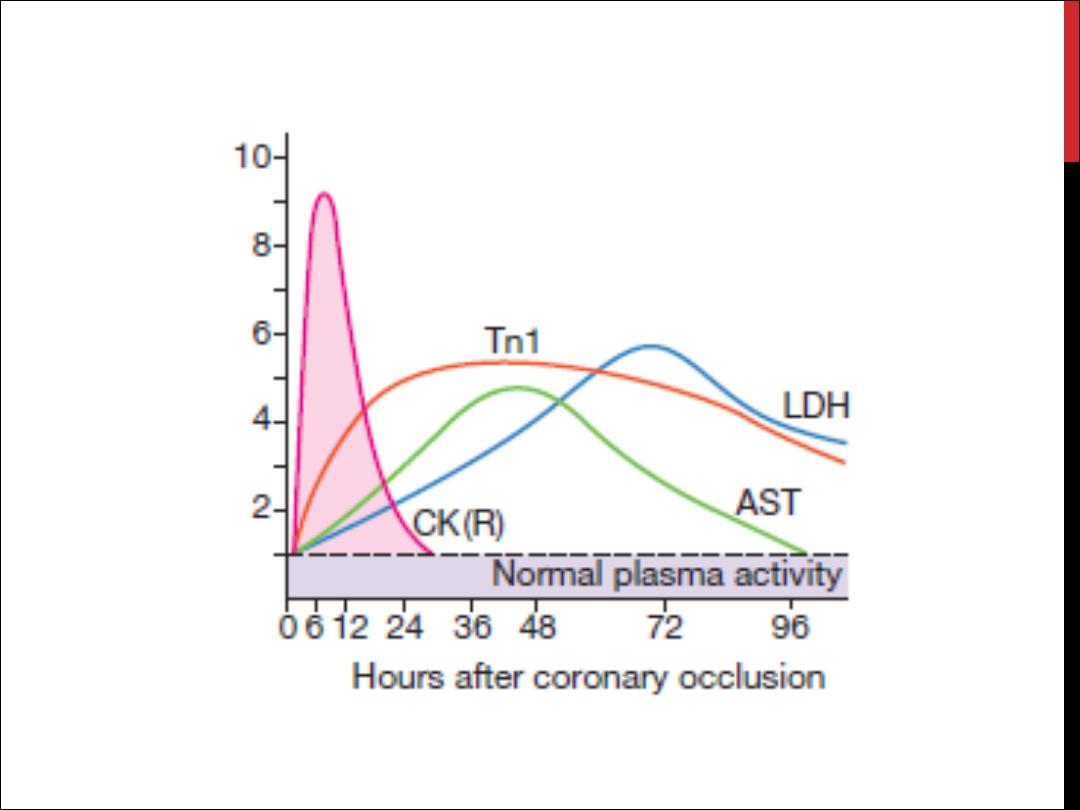

PLASMA CARDIAC BIOMARKERS

Other blood tests

Chest X-ray

Echocardiography

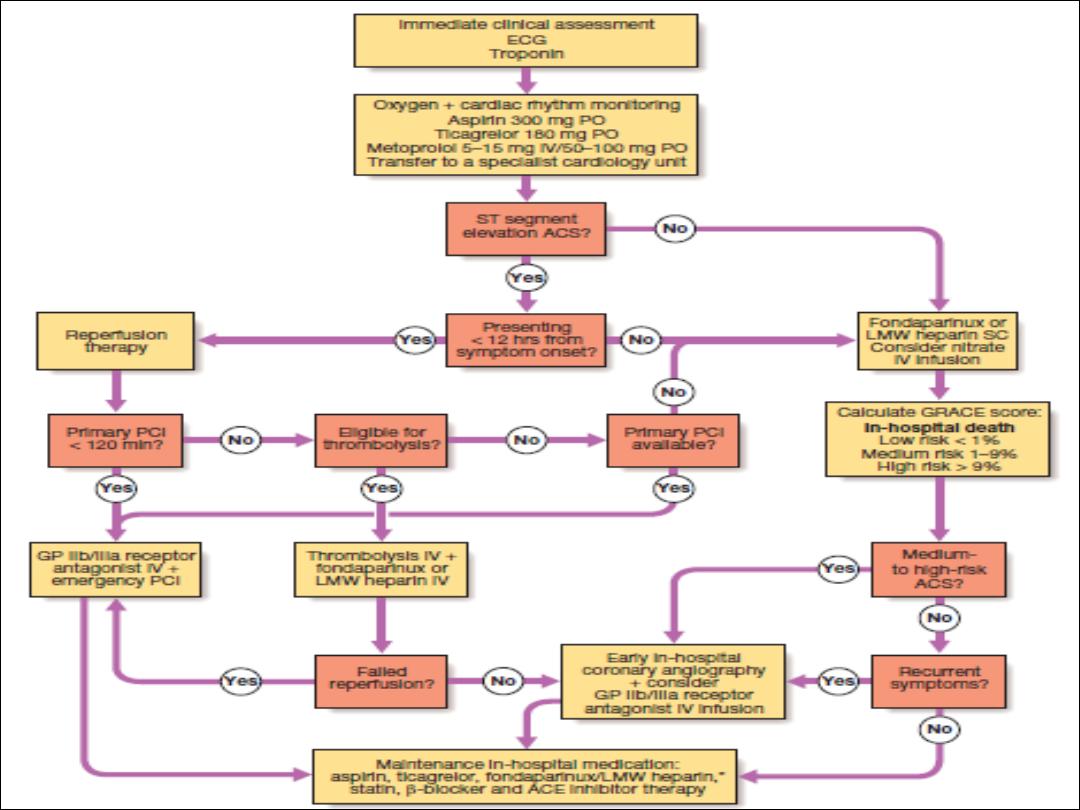

IMMEDIATE MANAGEMENT: THE

FIRST

12 HOURS

Addmission

Analgesia

Antithrombotic therapy

Anti-anginal therapy

Reperfusion therapy

PRIMARY PCI

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Absolute

•

ICH

•

Structural cerebral vascular lesion

•

Ischaemic strok within 3 months

•

Malig. Intracranial neoplasm

•

Active bleeding and bleeding diathesis

•

Aortic dissection

•

Significant closed –head or facial trauma within 3 months

Relative

•

Poorly controlled HT. ( SBP ≥ 180)

•

Ischaemic strok ≥ 3 months

•

Dementia

•

Prolonged traumatic resuscitation ( ≥ 10 min)

•

Recent internal bleeding ( within 2-4 weeks)

•

Non compressible vascular puncture

•

Active peptic ulcer

•

Current use of anticoagulants

•

Pregnancy

•

Prior exposure ( for streptokinase)

COMPLICATIONS OF ACUTE

CORONARY SYNDROME

Arrhythmias

Ischaemia

Acute circulatory failure

Pericarditis

Mechanical complications

Embolism

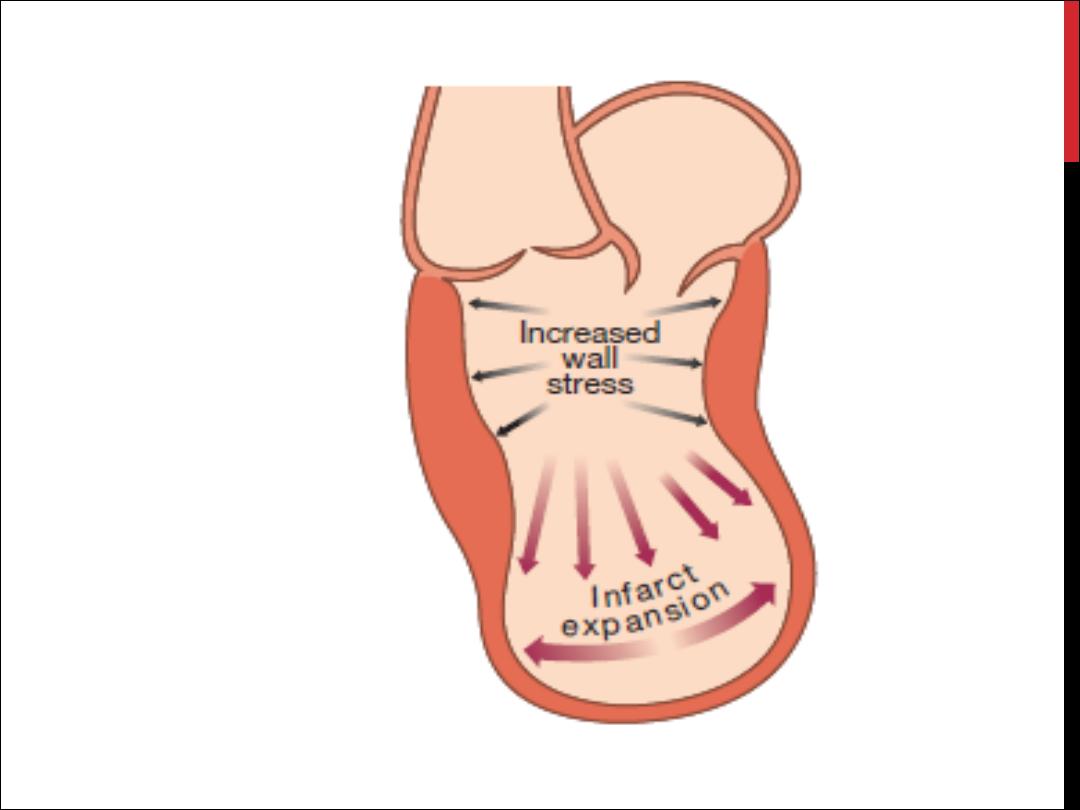

Impaired ventricular function, remodelling and ventricular aneurysm

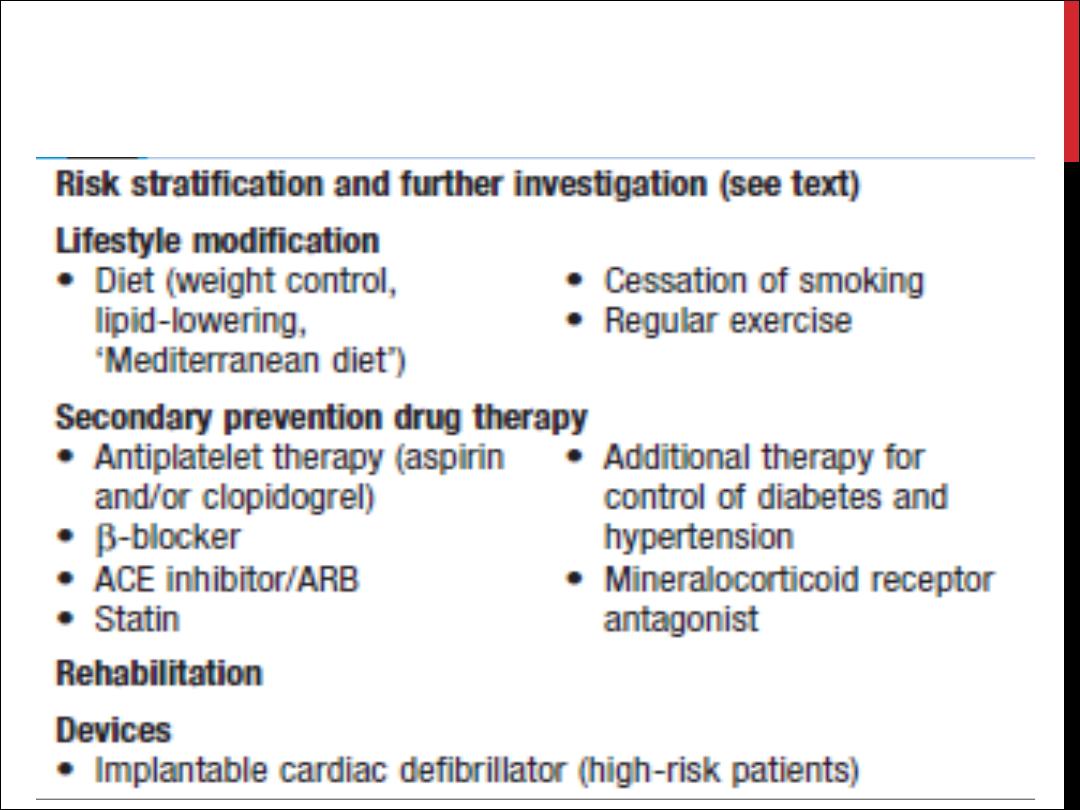

LATE MANAGEMENT OF ML

Valvular heart

diseases

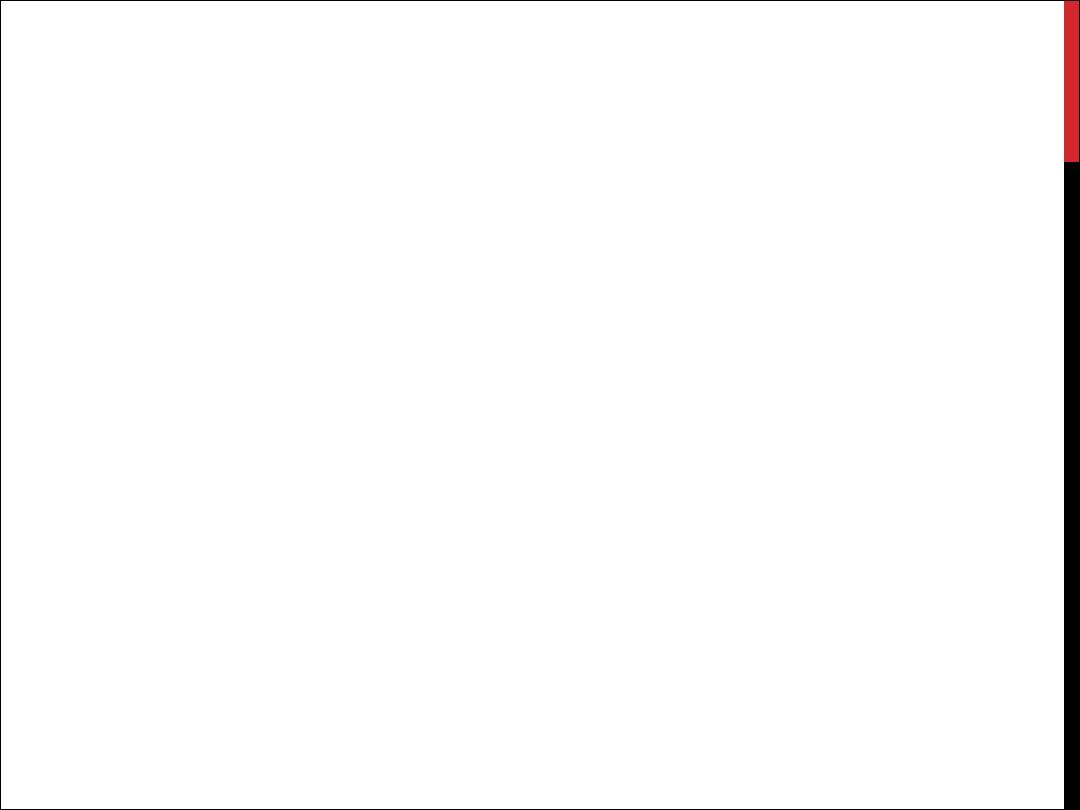

Mitral Stenosis

AETIOLOGY

1- Congenital

2- acquired

Rheumatic

Degenerative

pathophysiology

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

DEFINITIONS OF SEVERITY OF

MITRAL STENOSIS

Valve Area:

•

<1.0 cm2 è Severe

•

1.0-1.5 cm2 è Moderate

•

>1.5-2.5 cm2 è Mild

Mean gradient:

•

>10 mmHg è Severe

•

5-10 mmHg è Moderate

•

<5 mmHg è Mild

CLINICAL FEATURES

Symptoms

Breathlessness (pulmonary congestion)

Fatigue (low cardiac output)

Oedema, ascites (right heart failure)

Palpitation (atrial fibrillation)

Haemoptysis (pulmonary congestion, pulmonary embolism)

Cough (pulmonary congestion)

Chest pain (pulmonary hypertension)

Thromboembolic complications (e.g. stroke, ischaemic limb)

Signs

Atrial fibrillation

Mitral facies

Auscultation

Loud first heart sound, opening snap

Mid-diastolic murmur

Crepitations, pulmonary oedema, effusions (raised PCWP)

RV heave, loud P2 (pulmonary hypertension)

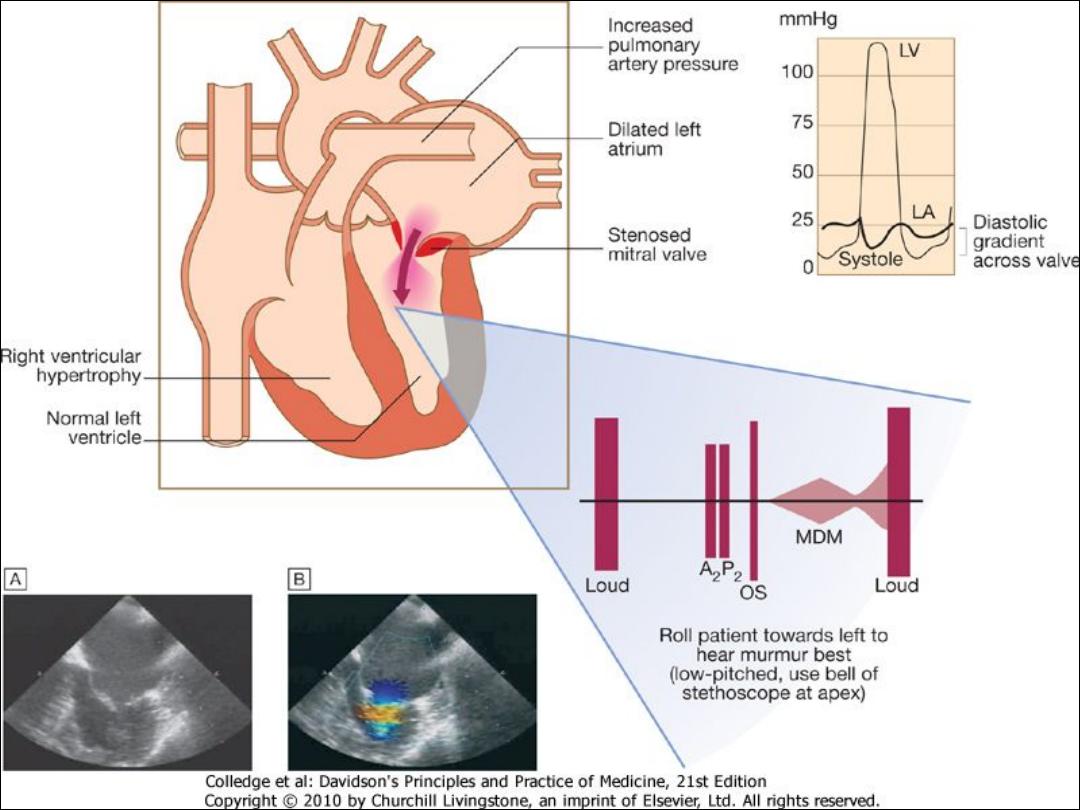

Investigations

ECG

P mitrale or atrial fibrillation

Right ventricular hypertrophy: tall R waves in V1-V3

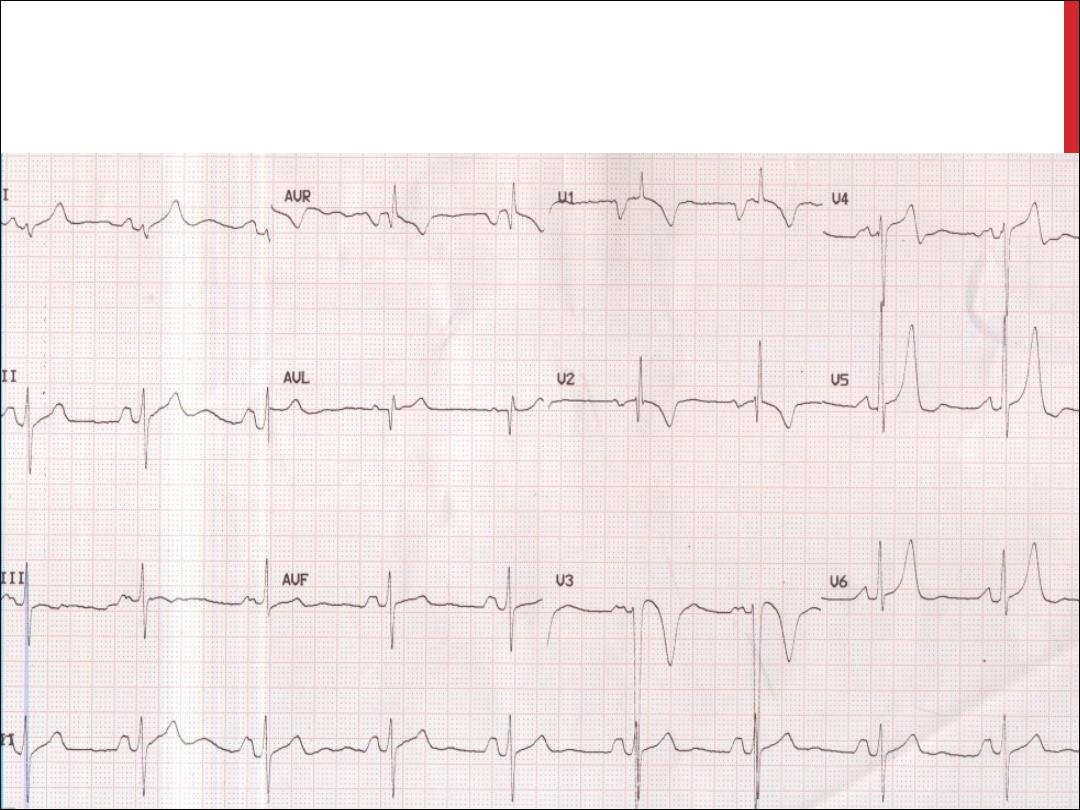

CXR

Enlarged LA and appendage

Signs of pulmonary venous congestion

Echo

Thickened immobile cusps

Reduced valve area

Reduced rate of diastolic filling of LV

Enlarged LA

Doppler

Pressure gradient across mitral valve

Pulmonary artery pressure

Left ventricular function

Cath

Coronary artery disease

Mitral stenosis and regurgitation

Pulmonary artery pressure

Echocardiogram in mitral

\

Desktop

\

SHOKRY

\

Users

\

C:

YouTube.flv

-

stenosis

MANAGEMENT

1- Medical management

Anticoagulation

Rate control

Diuretics

2- Mitral balloon valvuloplasty

Significant symptoms

Isolated mitral stenosis

No (or trivial) mitral regurgitation

Mobile, non-calcified valve ( Wilkins score )

LA free of thrombus

3- Valvotomy and Valve replacement

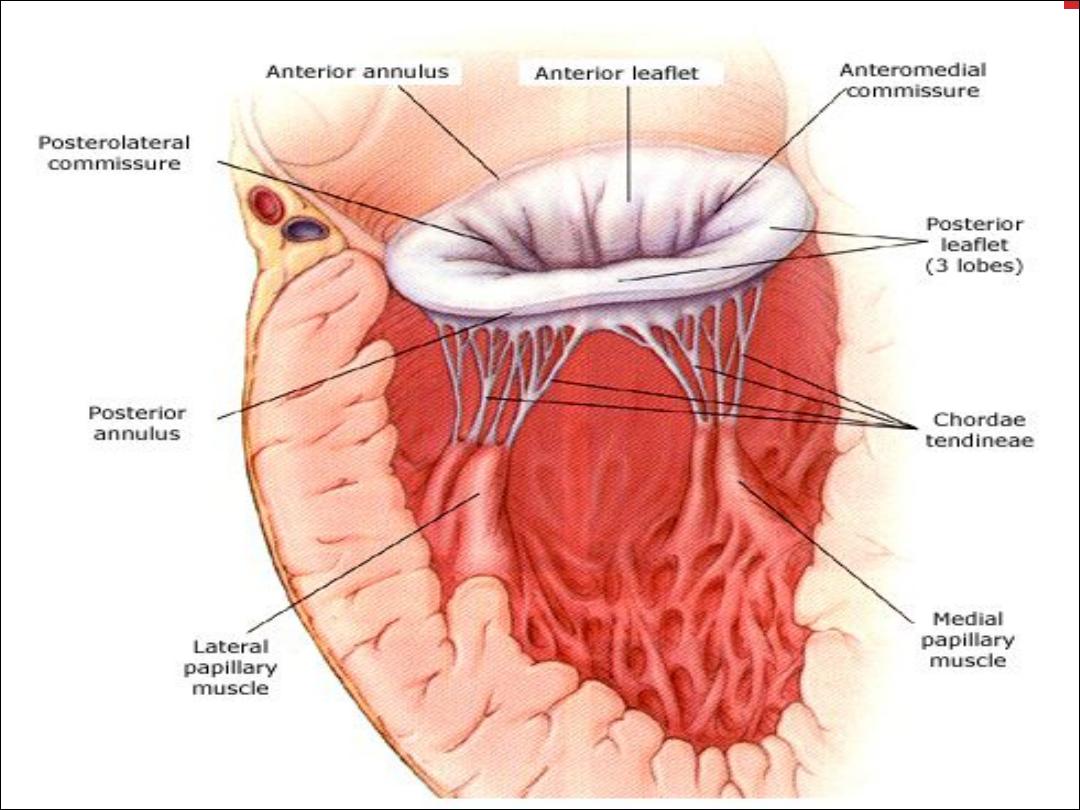

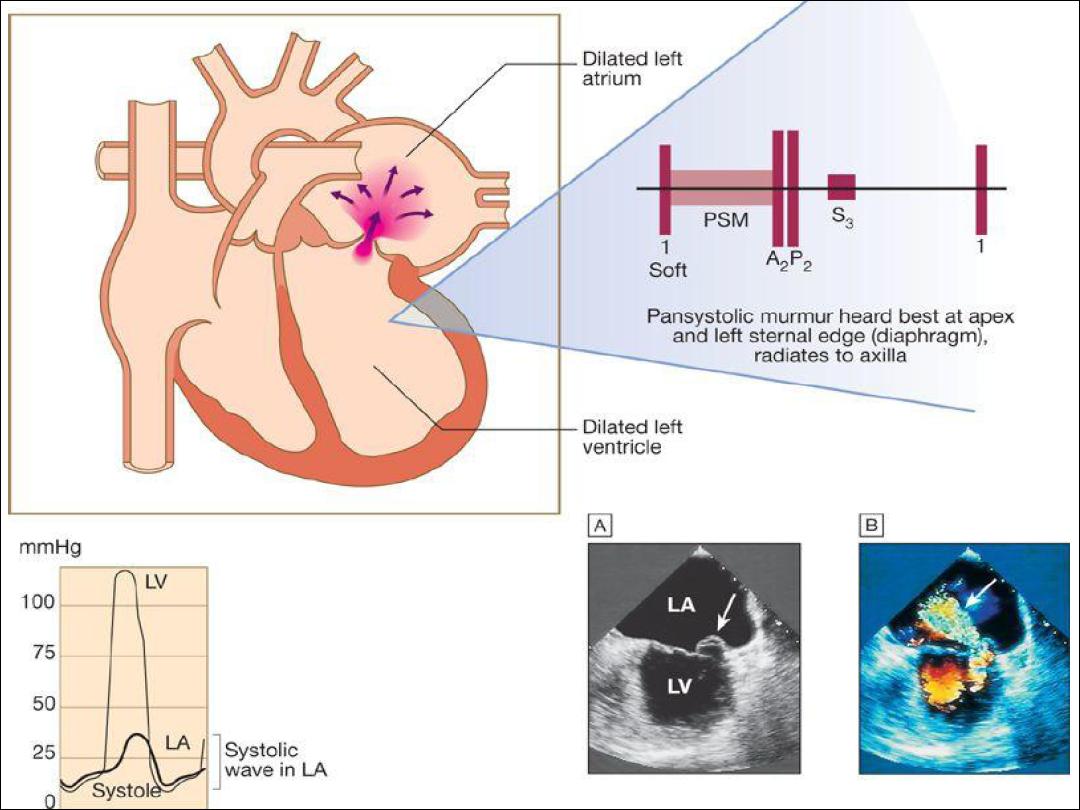

MITRAL REGURGITATION

Causes of mitral regurgitation

Mitral valve prolapse

Dilatation of the LV and mitral valve ring (e.g.

coronary artery disease,cardiomyopathy)

Damage to valve cusps and chordae (e.g. rheumatic heart

disease,endocarditis)

Ischaemia or infarction of the papillary muscle

MI

MITRAL VALVE

PROLAPSE

Congenital anomalies

Degenerative myxomatous changes

Marfan syndrom

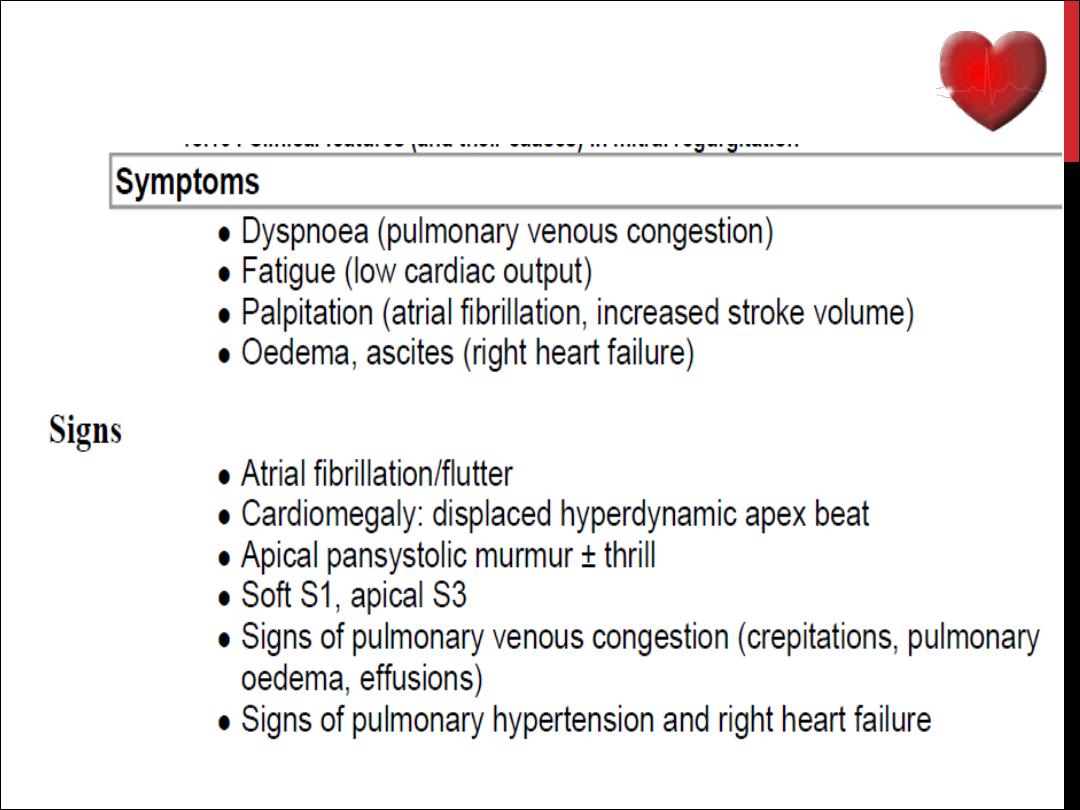

CLINICAL FEATURES

INVESTIGATIONS

MANAGEMENT

Medical management of MR

Diuretics

Vasodilators, e.g. ACE inhibitors

Digoxin if atrial fibrillation is present

Anticoagulants if atrial fibrillation is present

Surgical management

Repair

Replacement

AORTIC STENOSIS

Infants, children, adolescents

Congenital aortic stenosis

Congenital subvalvular aortic stenosis

Congenital supravalvular aortic stenosis

Young adults to middle-aged

Calcification and fibrosis of congenitally bicuspid aortic valve

Rheumatic aortic stenosis

Middle-aged to elderly

Senile degenerative aortic stenosis

Calcification of bicuspid valve

Rheumatic aortic stenosis

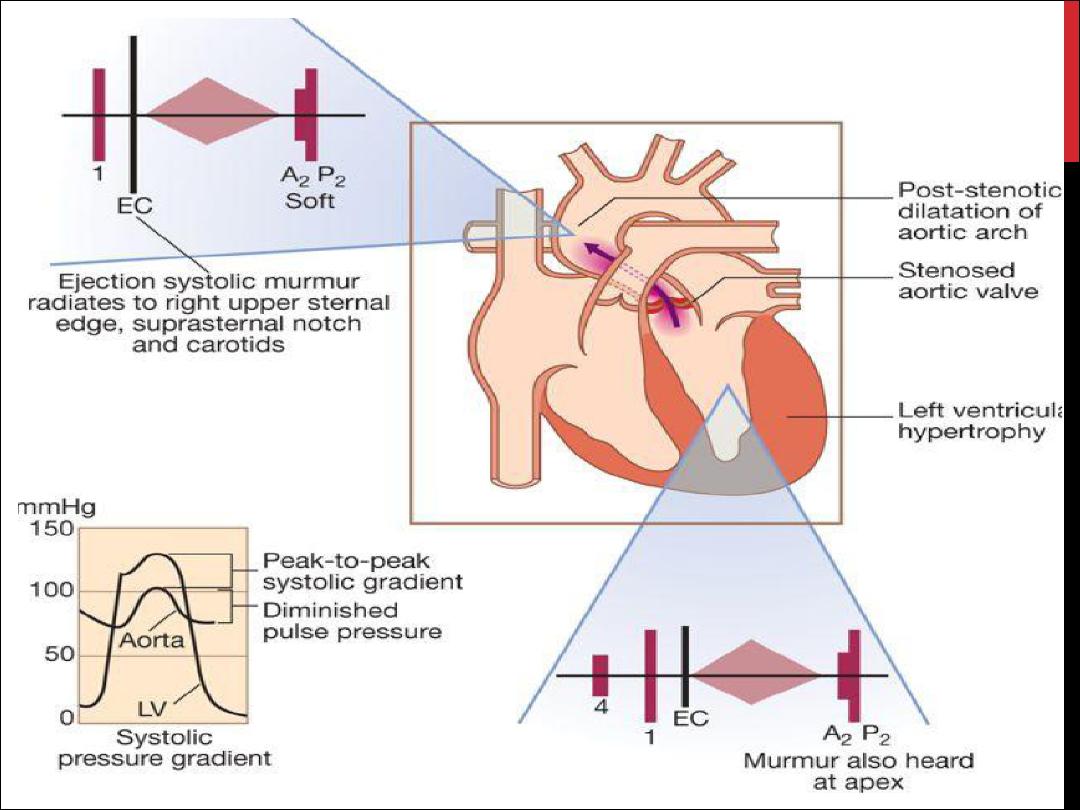

CLINICAL FEATURES

Symptoms

Mild or moderate stenosis: usually asymptomatic

Exertional dyspnoea

Angina

Exertional syncope

Sudden death

Episodes of acute pulmonary oedema

Signs

Ejection systolic murmur

Slow-rising carotid pulse

Narrow pulse pressure

Thrusting apex beat (LV pressure overload)

Signs of pulmonary venous congestion (e.g. crepitations)

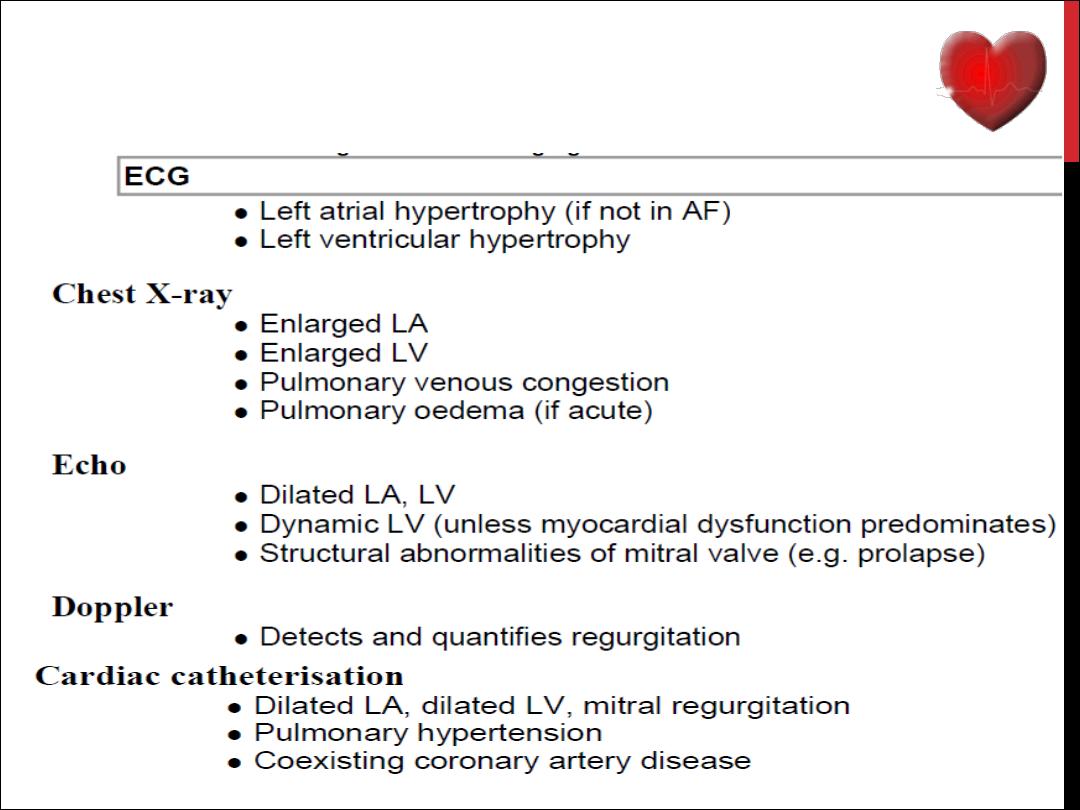

INVESTIGATIONS IN AORTIC STENOSIS

ECG

Left ventricular hypertrophy (usually)

Left bundle branch block

Chest X-ray

May be normal; sometimes enlarged LV and dilated ascending aorta on PA view,

calcified valve on lateral view

Echo

Calcified valve with restricted opening, hypertrophied Left ventricle

Doppler

Measurement of severity of stenosis

Detection of associated aortic regurgitation

Cardiac catheterisation

Mainly to identify associated coronary artery disease

May be used to measure gradient between LV and aorta

MANAGEMENT

Conservative

AVR

Balloon dilatation

TAVI

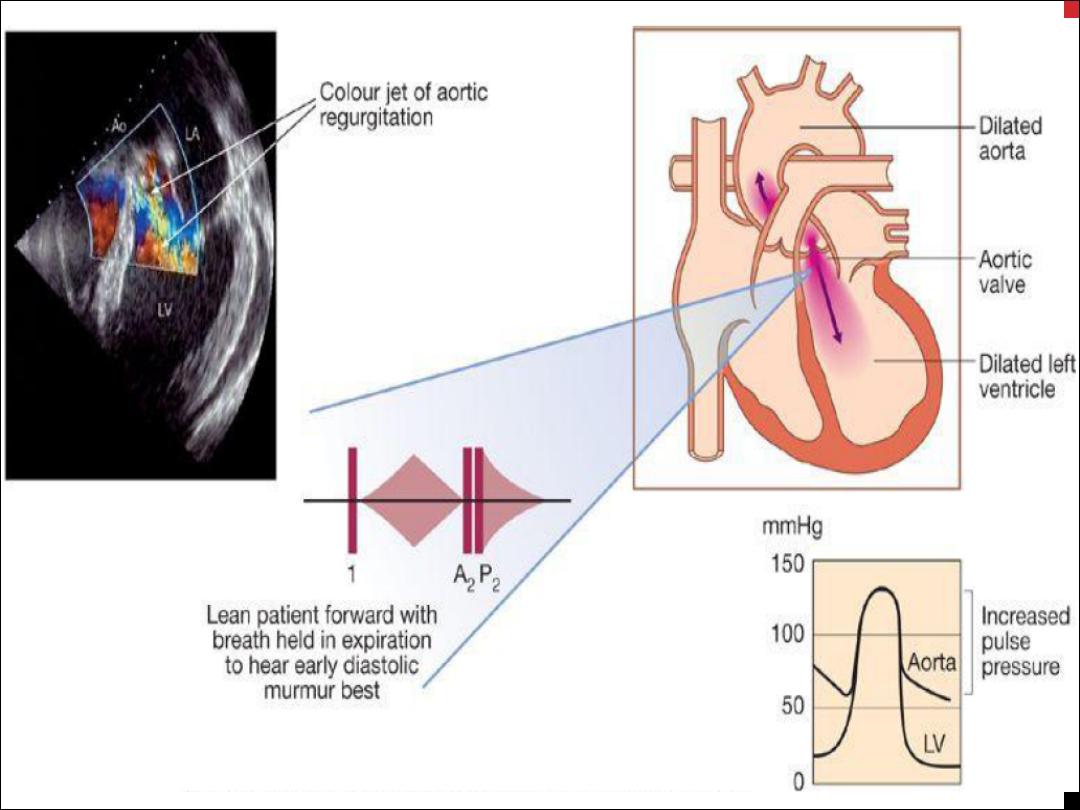

AORTIC REGURGITATION

Congenital

Bicuspid valve or disproportionate cusps

Acquired

Rheumatic disease

Infective endocarditis

Trauma

Aortic dilatation (Marfan's syndrome, aneurysm, dissection,

syphilis,ankylosing spondylitis)

CLINICAL FEATURES

Mild to moderate AR

Often asymptomatic

Awareness of heart beat, 'palpitations'

Severe AR

Breathlessness

Angina

Signs Pulses

Large-volume or 'collapsing' pulse

Low diastolic and increased pulse pressure

Bounding peripheral pulses

Capillary pulsation in nail beds: Quincke's sign

Femoral bruit ('pistol shot'): Duroziez's sign

Head nodding with pulse: de Musset's sign

Murmurs

Early diastolic murmur

Systolic murmur (increased stroke volume)

Austin Flint murmur (soft mid-diastolic)

Other signs

INVESTIGATIONS

ECG

Initially normal, later left ventricular hypertrophy and T-wave inversion

Chest X-ray

Cardiac dilatation, maybe aortic dilatation

Features of left heart failure

Echo

Dilated LV

Hyperdynamic LV

Fluttering anterior mitral leaflet

Doppler detects reflux

Cardiac catheterisation (may not be required)

Dilated LV

Aortic regurgitation

Dilated aortic root

MANAGEMENT

underlying conditions

Systolic BP should be controlled with vasodilating

drugs such as nifedipine or ACE inhibitors

Surgery

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

This is due to microbial infection of a heart

valve (native or prosthetic), the lining of a

cardiac chamber or blood vessel, or a

congenital anomaly

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

occurs at sites of pre-existing endocardial damage

Many acquired and congenital cardiac lesions are

vulnerable to endocarditis

Infection tends to occur at sites of endothelial damage

vegetations composed of organisms, fibrin and platelets

grow and may become large enough to cause obstruction

or embolism

Valve regurgitation may develop or increase

Extracardiac manifestations such as vasculitis and skin

lesions are due to emboli or immune complex deposition

Mycotic aneurysms may develop in arteries at the site of

infected emboli

MICROBIOLOGY

Over three-quarters of cases are due to streptococci or

staphylococci (viridans group )

Other organisms Enterococcus faecalis, E. faecium and

Strep. Bovis

Staph. aureus has now overtaken streptococci

Post-operative endocarditis: coagulase-negative

staphylococcus (Staph. epidermidis , Staph. Lugdenensis )

Q fever endocarditis due to Coxiella burnetii

HACEK group and Brucella

Yeasts and fungi (Candida, Aspergillus)

INCIDENCE

5 to 15 cases per 100 000 per annum

rheumatic heart disease in 24%

congenital heart disease in 19%

other cardiac abnormality (e.g. calcified aortic

valve, floppy mitral valve) in 25%.

32% not have a pre-existing cardiac

abnormality

CLINICAL FEATURES

Subacute endocarditis

Acute endocarditis

Post-operative endocarditis

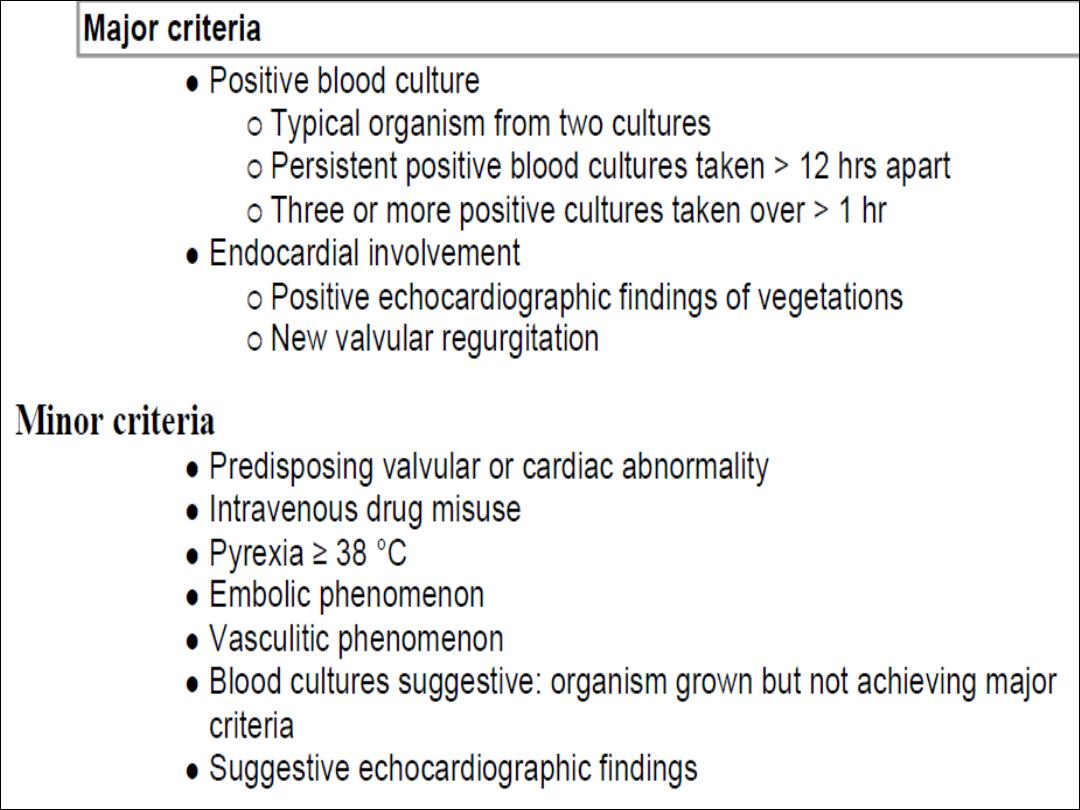

INVESTIGATIONS

Blood culture

Echocardiography

ESR, anaemia, and leucocytosis

CRP ; Proteinurea ; microscopic haematuria

ECG

CXR

MANAGEMENT

The case fatality 20%

A multidisciplinary approach

Empirical treatment

A 2-week treatment regimen may be sufficient for fully

sensitive strains of Strep. viridans and Strep. Bovis

Cardiac surgery

Heart failure due to valve damage

Failure of antibiotic therapy

Large vegetations on left-sided heart valves

Abscess formation