Infective endocarditis

Pathophysiology

•

typically occurs at sites of preexisting endocardial damage

•

virulent or aggressive organisms (e.g.

Staphylococcus aureus

) can cause

endocarditis in a previously normal heart

•

Many acquired and congenital cardiac lesions are vulnerable to endocarditis,

particularly areas of endocardial damage caused by a high-pressure jet of blood

•

•

The avascular valve tissue and presence of fibrin and platelet aggregates help to

protect proliferating organisms from host defence mechanisms

•

vegetations composed of organisms, fibrin and platelets grow and may become

large enough to cause obstruction or embolism

•

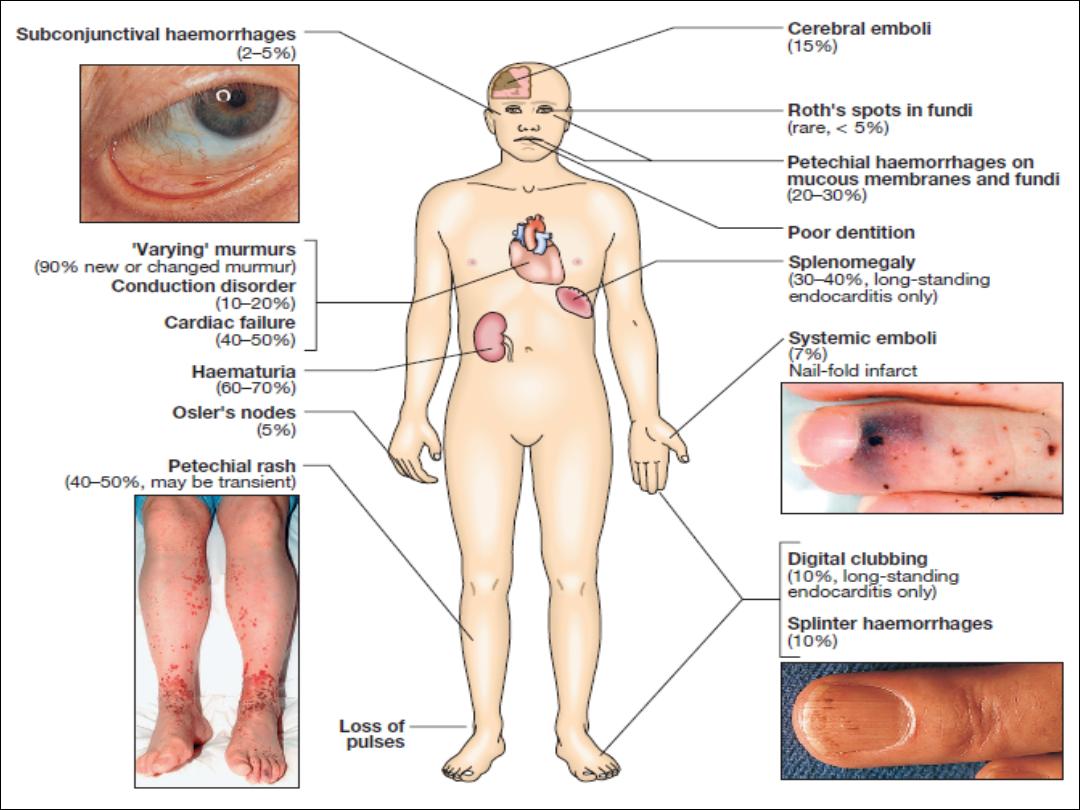

Extracardiac manifestations, such as vasculitis and skin lesions, are due to emboli

or immune complex deposition

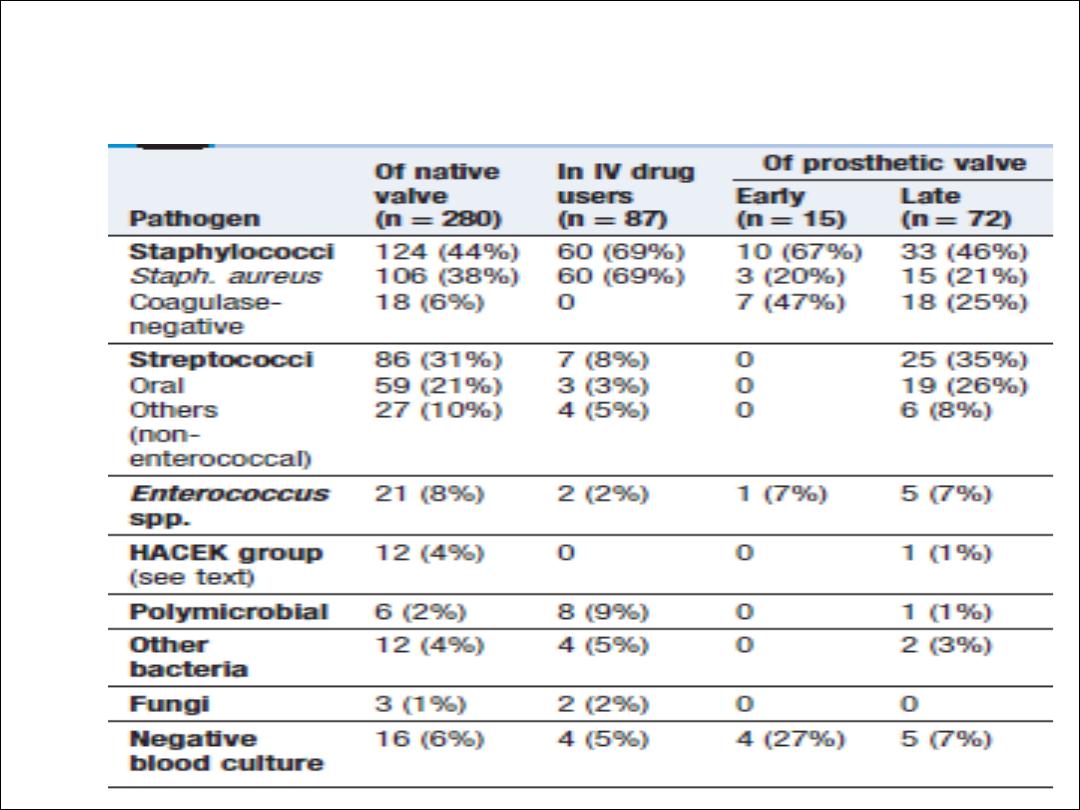

Microbiology

• Over three-quarters of cases are caused by streptococci or staphylococci

•

Strep. milleri

and

Strep. bovis

endocarditis is associated with large-bowel

neoplasms.

•

Staph. aureus

has now overtaken streptococci as the most common

cause of acute endocarditis

• Post-operative endocarditis .The most common organism is a coagulase-

negative staphylococcus (

Staph. epidermidis

)

• Q fever endocarditis due to

Coxiella burnetii

, : contact with farm animals.

The aortic valve is usually affected and there may also be hepatitis,

pneumonia and purpura. Life-long antibiotic therapy may be required.

• HACEK are slow-growing, fastidious organisms that are only revealed

after prolonged culture and may be resistant to penicillin.

•

Brucella

• Yeasts and fungi (

Candida, Aspergillus

)

Microbiology of infective endocarditis

Incidence

• 5 to 15 cases per 100 000 per annum

• 50% of patients are over 60 years

• rheumatic heart disease in 24%

• congenital heart disease in 19%

• other cardiac abnormalities (calcified aortic valve, floppy mitral valve) in

25%

• 32% were not thought to have a pre-existing cardiac abnormality

Clinical features

•

Subacute endocarditis

•

Acute endocarditis

•

Post-operative endocarditis

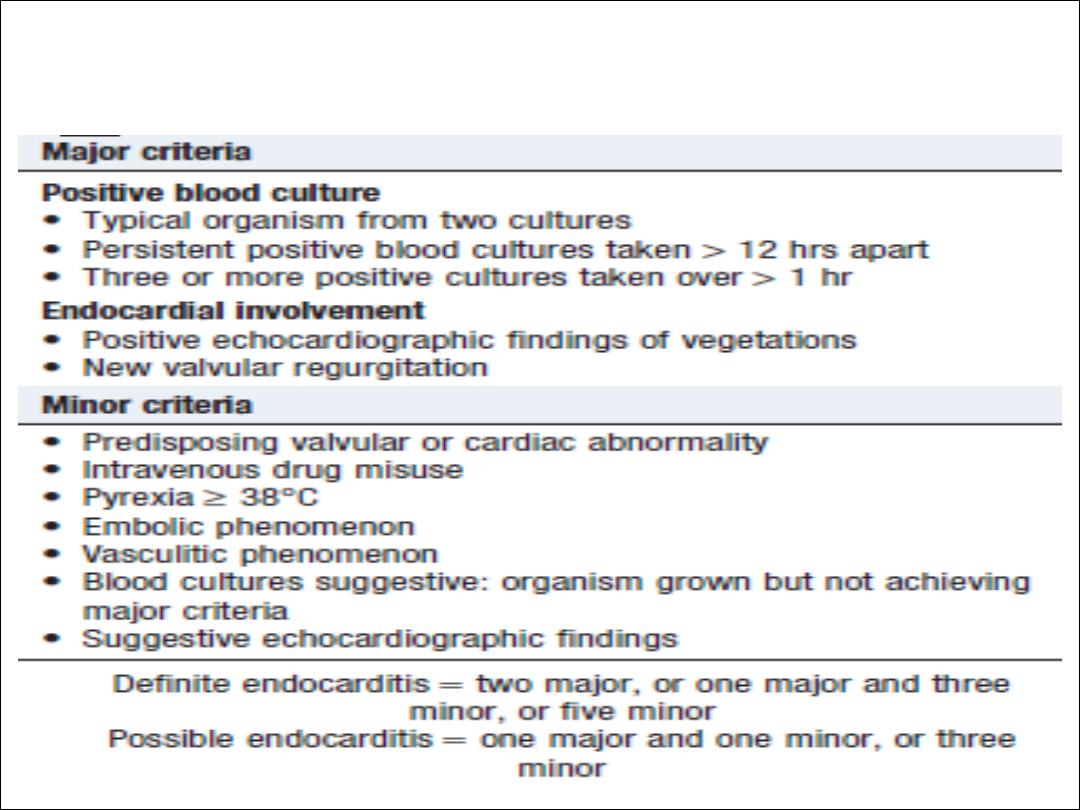

modified Duke criteria

Investigations

• Blood culture

• Echocardiography

• ESR , CRP , CBC

• ECG

• CXR

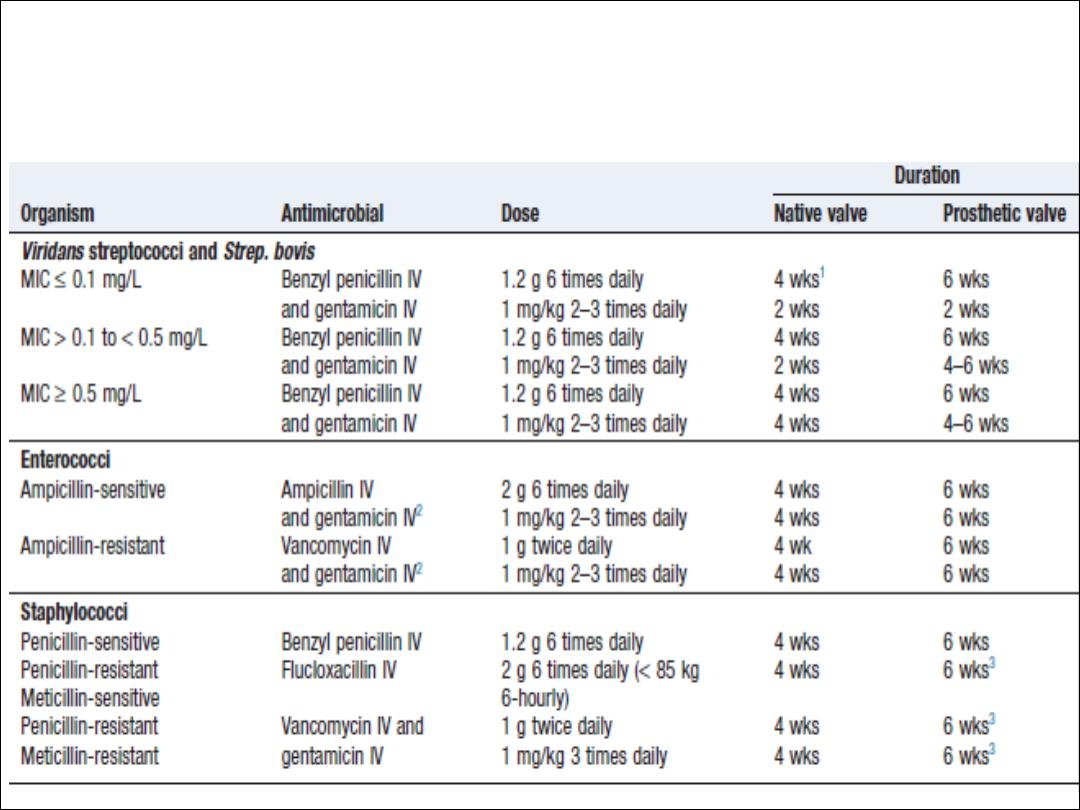

Management

• The case fatality of bacterial endocarditis is approximately 20 %

• A multidisciplinary approach increases the chance of better outcome

• Empirical treatment depends on the mode of presentation, the

suspected organism, and whether the patient has a prosthetic valve or

penicillin allergy

• If the presentation is acute, flucloxacillin and gentamicin are

recommended, while for a subacute or indolent presentation, benzyl

penicillin and gentamicin are preferred

• In those with penicillin allergy, a prosthetic valve or suspected meticillin-

resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA) infection, triple therapy with

vancomycin, gentamicin and oral rifampicin should be considered

• A 2-week treatment regimen may be sufficient for fully sensitive strains

of Strep. viridans and Strep. bovis, provided specific conditions are met

Conditions for the short-course treatment

of

Strep. viridans/bovis

endocarditis

Ø

• Native valve infection

Ø

• MIC ≤ 0.1 mg/L

Ø

• No adverse prognostic factors (e.g. heart failure,

aortic regurgitation, conduction defect)

Ø

• No evidence of thromboembolic disease

Ø

• No vegetations > 5 mm diameter

Ø

• Clinical response within 7 days

Antimicrobial treatment of common causative

organisms in infective endocarditis

Indications for cardiac surgery in

infective endocarditis

Ø

• Heart failure due to valve damage

Ø

• Failure of antibiotic therapy (persistent/uncontrolled

infection)

Ø

• Large vegetations on left-sided heart valves with

evidence or‘high risk’ of systemic emboli

Ø

• Abscess formation

N.B. Patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis or fungal endocarditis often require

cardiac surgery.

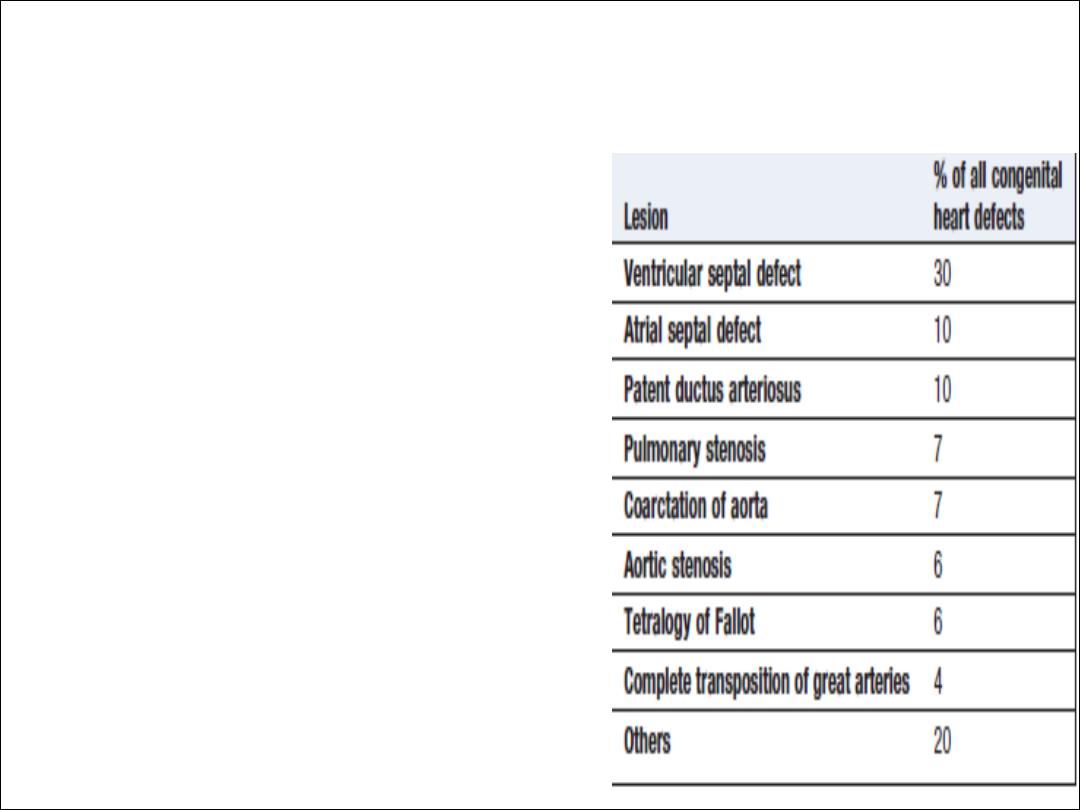

CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

Aetiology and incidence

• 0.8% of live births

• Maternal infection or exposure to

drugs or toxins may cause congenital

heart disease.

Rubella , alcohol , SLE

• Genetic or chromosomal

abnormalities, such as Down’s

syndrome , Marfan syndrom and

Digeorge syndrom

Clinical features

• Clinical signs vary with the anatomical lesion

• Symptoms may be absent, or the child may be breathless

or fail to attain normal growth and development

• Some defects are not compatible with extrauterine life

• Features of other congenital conditions, such as Marfan’s

syndrome or Down’s syndrome, may also be apparent

• Early diagnosis is important because many types of

congenital heart disease are amenable to surgery

•

Central cyanosis and digital clubbing

•

Growth retardation and learning difficulties

•

Syncope

•

Pulmonary hypertension and Eisenmenger’s

syndrome

Pregnancy

• Obstructive lesions (e.g. severe aortic stenosis): poorly

tolerated and associated with significant maternal morbidity and

mortality.

• Cyanotic conditions (e.g. Eisenmenger’s syndrome):

especially poorly tolerated and pregnancy should be avoided.

• Surgically corrected disease: patients often tolerate

pregnancy well.

• Children of patients with congenital heart disease: 2–5%

will be born with cardiac abnormalities, especially if the mother is

affected.

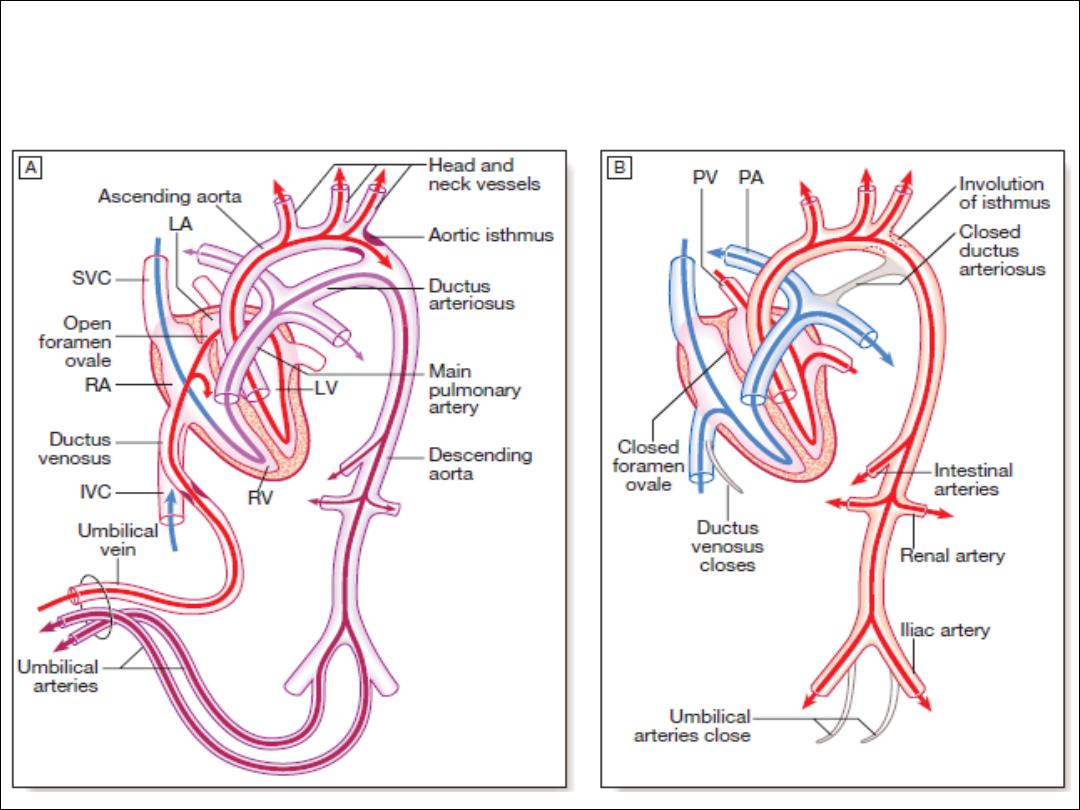

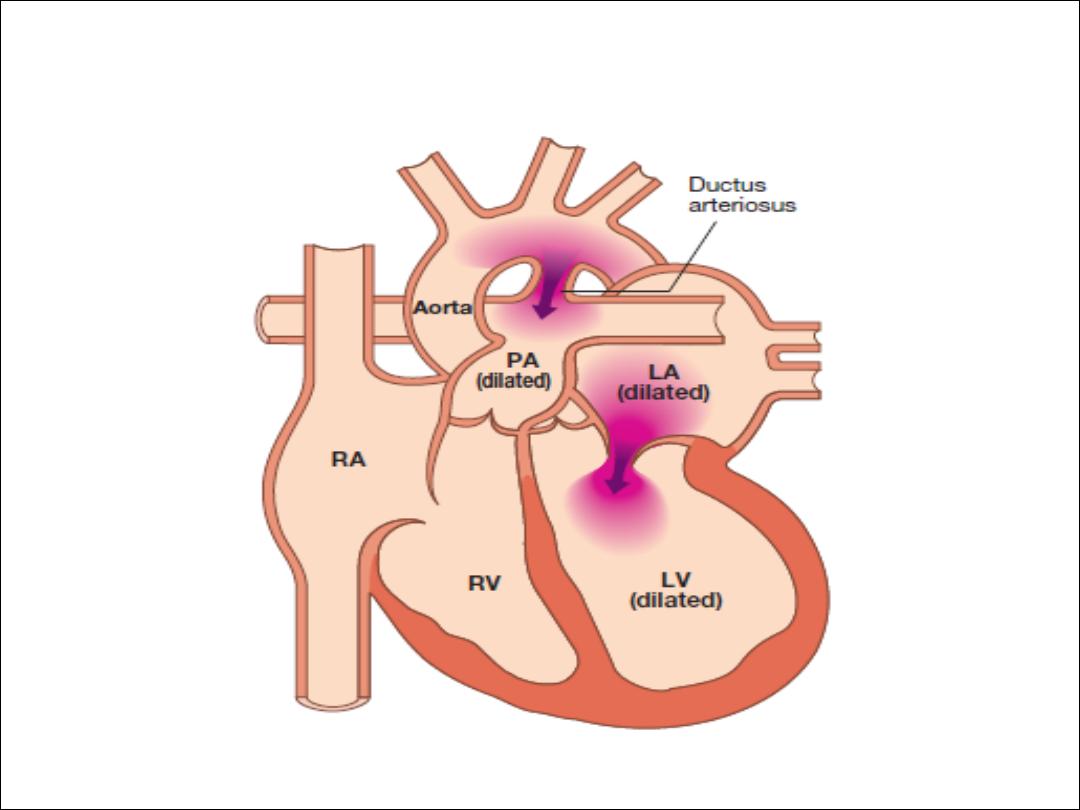

Persistent ductus arteriosus

Aetiology

• Normally, the ductus closes soon after birth but sometimes

fails to do so

• Persistence of the ductus is associated with other

abnormalities and is more common in females.

• there will be a continuous arteriovenous shunt

• 50% of the left ventricular output is recirculated through the

lungs

Clinical features

• small shunts there may be no symptoms for years

• when the ductus is large, growth and development may be

retarded

• cardiac failure may eventually ensue, dyspnoea being the first

symptom

• continuous ‘machinery’ murmur is heard

•

Persistent ductus with reversed shunting

Management

• A patent ductus is closed at cardiac catheterisation

with an implantable occlusive device

•

Pharmacological treatment in the neonatal period

(

prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor (indometacin or

ibuprofen)

Coarctation of the aorta

Aetiology

• occurs in the region where the ductus arteriosus joins the aorta, i.e. at

the isthmus just below the origin of the left subclavian artery

• twice as common in males and occurs in 1 in 4000 children

• associated with other abnormalities, most frequently bicuspid aortic valve

and ‘berry’ aneurysms of the cerebral circulation

• Acquired coarctation of the aorta is rare but may follow trauma or occur

as a complication of a progressive arteritis (Takayasu’s disease)

Clinical features and investigations

• coarctation is an important cause of cardiac failure in the newborn

• symptoms are often absent when it is detected in older children or adults

• Headaches , weakness or cramps in the legs , BP is raised in the upper

body

• Radiofemoral delay , systolic murmur may be be heard posteriorly or in the

aortic area with ejection click due to bicuspid AV

• CXR …… 3 sign and rib notching

• ECG ….LVH

• Echo. …..Confirm the diagnosis

• MRI is the best imaging modality

Management

• In untreated cases, death may occur from left ventricular failure,

dissection of the aorta or cerebral haemorrhage.

• Surgical correction is advisable in most cases

• Patients repaired in late childhood or adult life often remain

hypertensive or develop recurrent hypertension later on

• Recurrence of stenosis may occur as the child grows and this

may be managed by balloon dilatation and sometimes stenting

• Coexistent bicuspid aortic valve, which occurs in over 50% of

cases, may lead to progressive aortic stenosis or regurgitation,

and also requires long-term follow-up.

Atrial septal defect

• one of the most common congenital heart defects

• twice as frequently in females

• Most are ‘ostium secundum’ defects

• Ostium primum’ defects result from a defect in the

atrioventricular septum and are associated with a ‘cleft mitral

valve’ (split anterior leaflet).

• Pulmonary hypertension and shunt reversal sometimes

complicate atrial septal defect, but are less common and tend

to occur later in life

Clinical features and investigations

Symptoms

• Asymptomatic

• Dyspnea

• Chest infection

• HF

• Arrythmias , AF

Signs

• Wide fixed splitting S2

• Systolic flow murmur

• Diastolic flow murmur

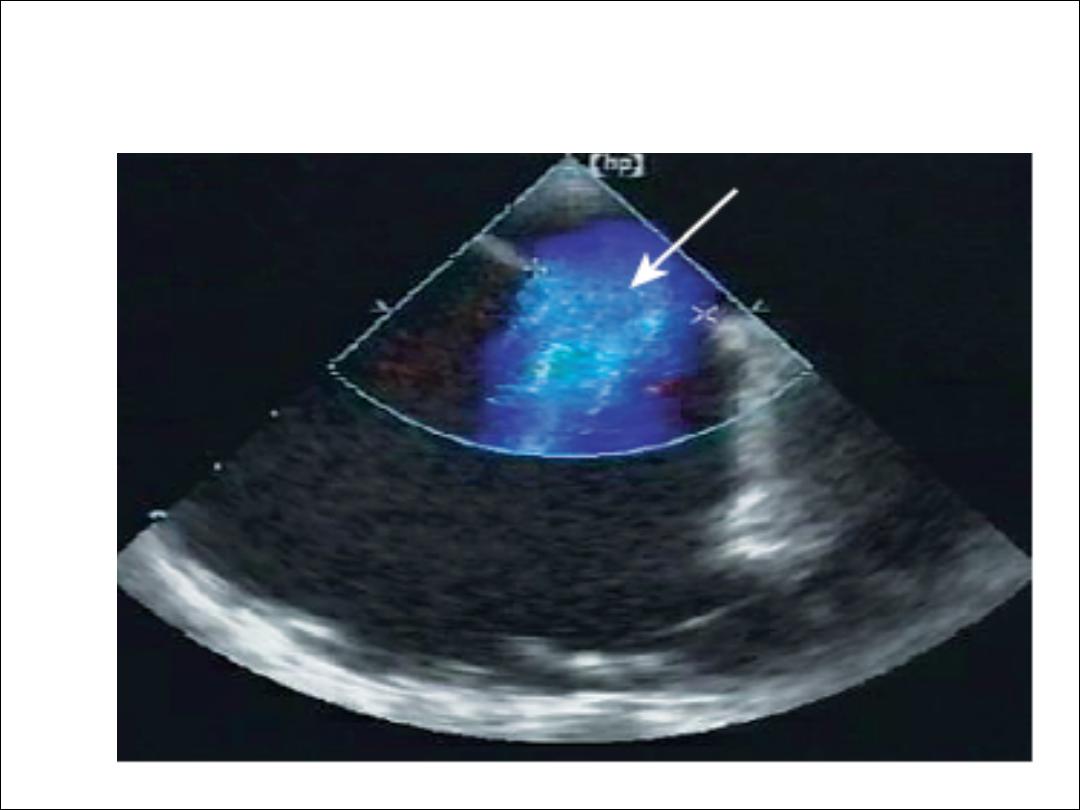

Investigations

• ECG :- RBBB , RAD and in case of primum defect

LAD

• CXR : cardiomegaly ; pul plethora , prominent PA

• Echo :- shows the defect , RV and PA dilatation

• TEE

TEE

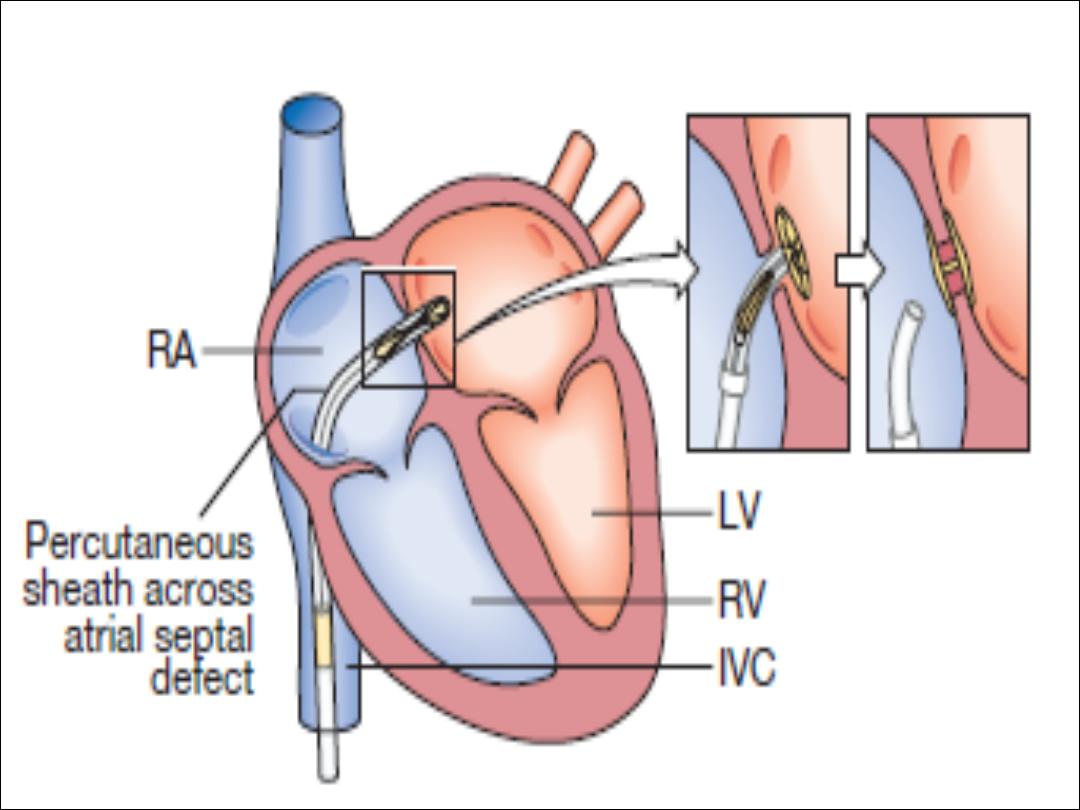

Management

• Atrial septal defects in which pulmonary flow is

increased 50% above systemic flow (i.e. flow ratio of

1.5 : 1) are often large enough to be clinically

recognisable and should be closed

• Cath or surgery

• Severe pulmonary hypertension and shunt reversal

are both contraindications to closure

Ventricular septal defect

Aetiology

• Congenital and acquired

• Embryologically, the interventricular septum has a

membranous and a muscular portion

• Most congenital defects are ‘perimembranous

• the most common congenital cardiac defect, occurring once

in 500 live births.

• Acquired ventricular septal defect may result from rupture as

a complication of acute MI or, rarely, from trauma.

Clinical features

• pansystolic murmur, usually heard best at the left sternal edge but

radiating all over the precordium

• maladie de Roger :- small defect producing loud murmur in the absence

of other haemodynamic disturbance

• Congenital ventricular septal defect may present as cardiac failure in

infants, as a murmur with only minor haemodynamic disturbance in older

children or adults, or, rarely, as Eisenmenger’s syndrome

• If cardiac failure complicates a large defect, it only becomes apparent in

the first 4–6 weeks of life

• The chest X-ray shows pulmonary plethora and the ECG shows bilateral

ventricular hypertrophy.

• Echo .

Management and prognosis

• Small ventricular septal defects require no specific

treatment

• HF : digoxin and diuretics

• Persisting failure is an indication for closure of the defect by

cath. or surgery

• Except in Eisenmenger’s syndrome, long-term prognosis is

very good in congenital ventricular septal defect

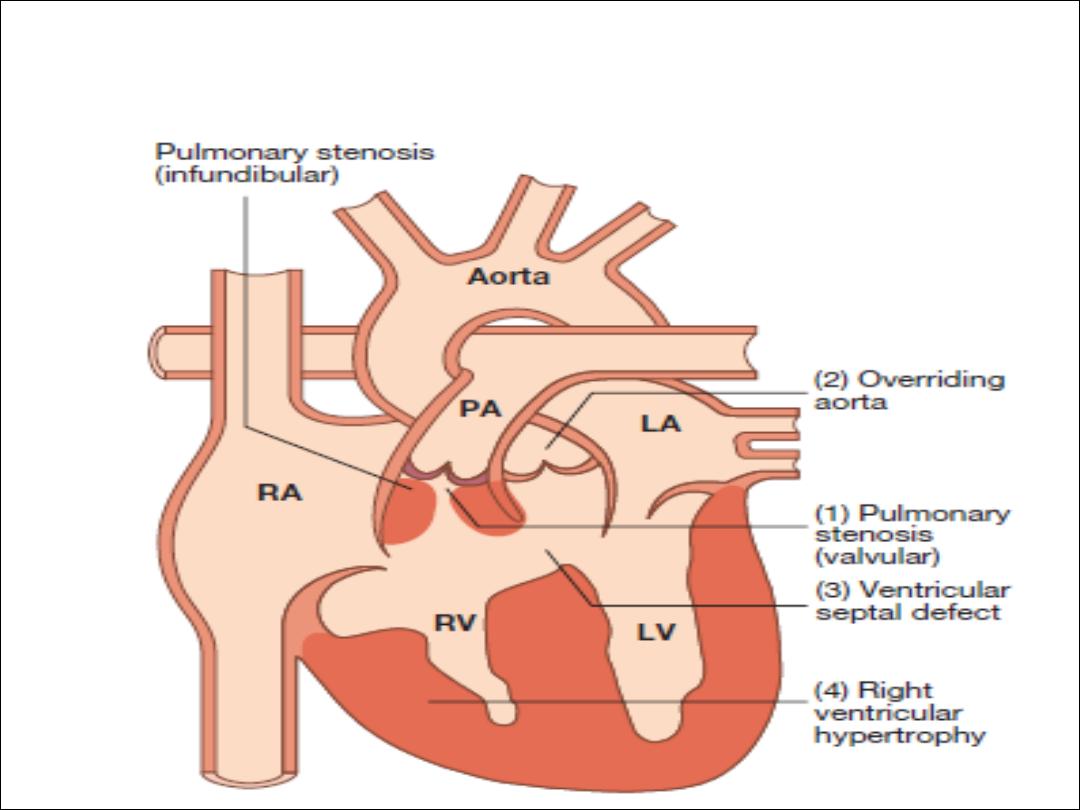

Tetralogy of Fallot

Aetiology

• The embryological cause is abnormal development of

the bulbar septum that separates the ascending aorta

from the pulmonary artery

• The defect occurs in about 1 in 2000 births and is the

most common cause of cyanosis in infancy after the

first year of life.

Clinical features

• Children are usually cyanosed but this may not be the case in the neonate

• The subvalvular component of the RV outflow obstruction is dynamic and

may increase suddenly under adrenergic stimulation

• Fallot’s spells

• In older children, Fallot’s spells are uncommon but cyanosis becomes

increasingly apparent, with stunting of growth, digital clubbing and

polycythaemia

• Fallot’s sign : Some children characteristically obtain relief by squatting after

exertion

• On examination, cyanosis with a loud ejection systolic murmur in the

pulmonary area

• cyanosis may be absent in the newborn or in patients with only mild right

ventricular outflow obstruction (‘acyanotic tetralogy of Fallot’)

Investigations and management

• ECG … RVH

• CXR … boot shaped heart

• Echo … Dx

• The definitive management is total surgical correction

• If the pulmonary arteries are too hypoplastic, then palliation in

the form of a Blalock–Taussig shunt

• The prognosis after total correction is good

• ICD is sometimes recommended in adulthood.

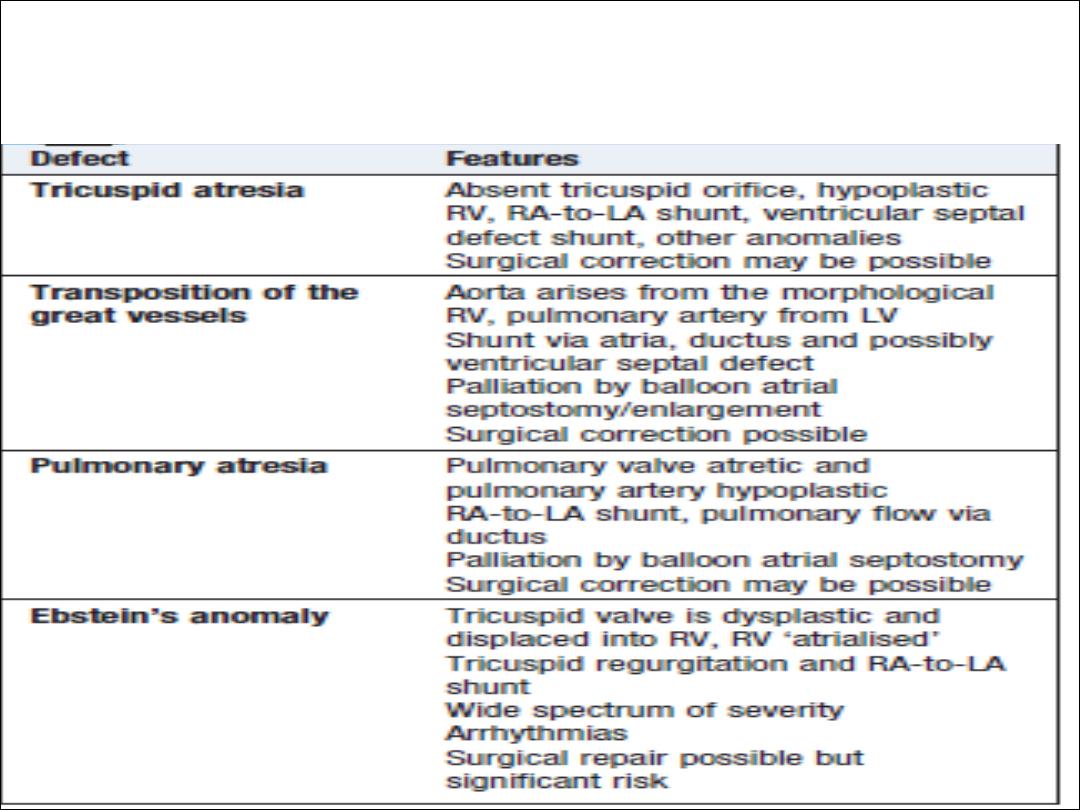

Other causes of cyanotic

congenital heart disease