Lec: 3

Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage

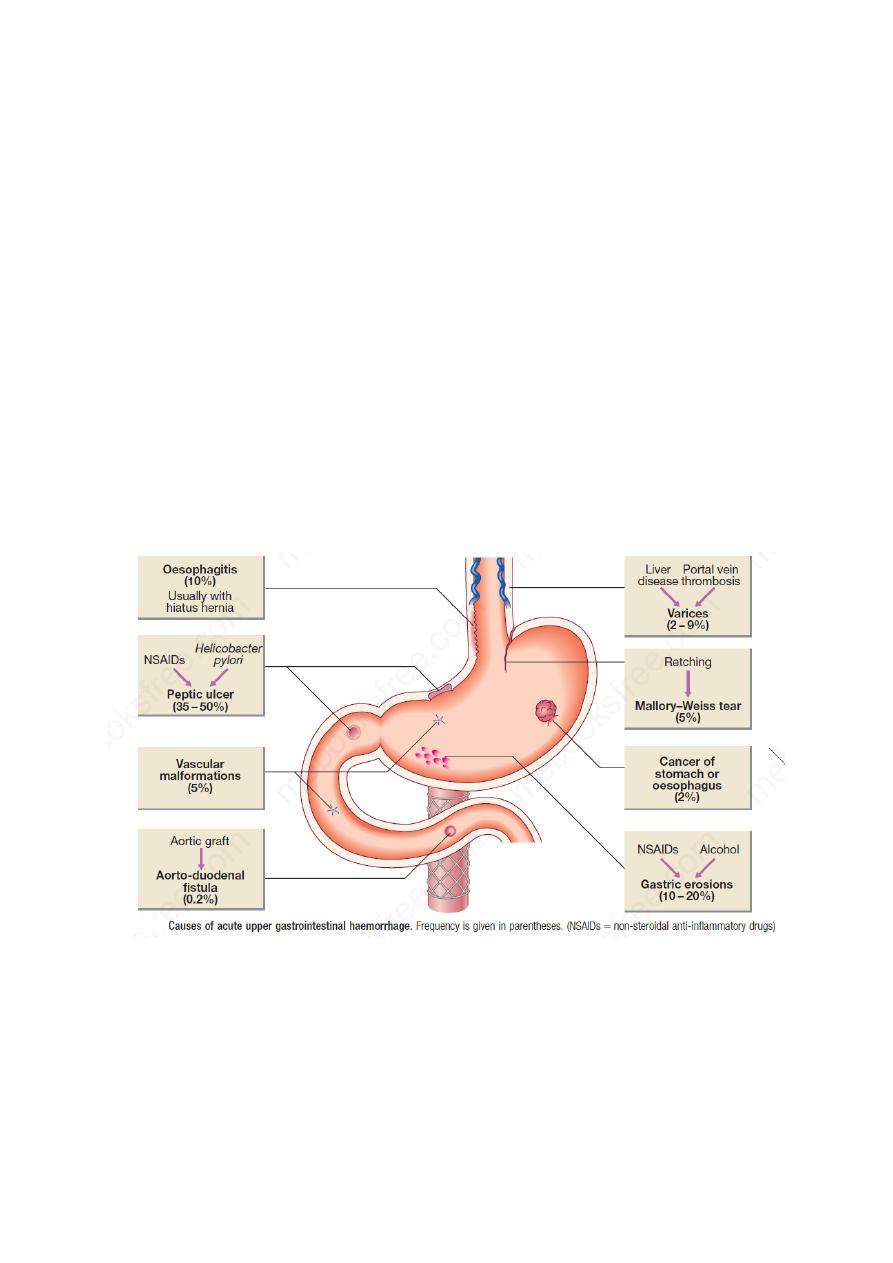

The common causes:

Esophagus

1- Oesophagitis (10%) Usually with hiatus hernia

2- Variceal bleeding (2 – 9%)

3- Mallory–Weiss tear (5%)

Stomach and duodenum

1- Peptic ulcer (35 – 50%)

2- Gastric erosions (10 – 20%)

3- Vascular malformations (5%)

Combine

Cancer of stomach or oesophagus (2%)

Clinical assessment

1- Haematemesis is red with clots when bleeding is rapid and profuse, or black

(‘coffee grounds’) when less severe.

2- Syncope may occur and is caused by hypotension from intravascular volume

depletion.

1

3- Symptoms of anaemia suggest chronic bleeding.

4- Melaena is the passage of black, tarry stools containing altered blood; it is

usually caused by bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract, although

haemorrhage from the right side of the colon is occasionally responsible. The

characteristic colour and smell are the result of the action of digestive enzymes

and of bacteria on haemoglobin. Other causes include Iron suplimentation,

Bismuth, blueberry, black liquorice and beetroot

5- Hematochezia

:

Severe acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding can sometimes

cause maroon or bright red stool.

Management

1. Intravenous access: The first step is to gain intravenous access using at least

one large-bore cannula.

2. Initial clinical assessment

• Define circulatory status. Severe bleeding causes tachycardia, hypotension ,

postural hypotension and oliguria. The patient is cold and sweating, and may be

agitated.

• Seek evidence of liver disease. Jaundice, cutaneous stigmata,

hepatosplenomegaly and ascites may be present in decompensated cirrhosis.

• Identify comorbidity. The presence of cardiorespiratory, cerebrovascular or

renal disease is important, both because these may be worsened by acute

bleeding and because they increase the hazards of endoscopy and surgical

operations.

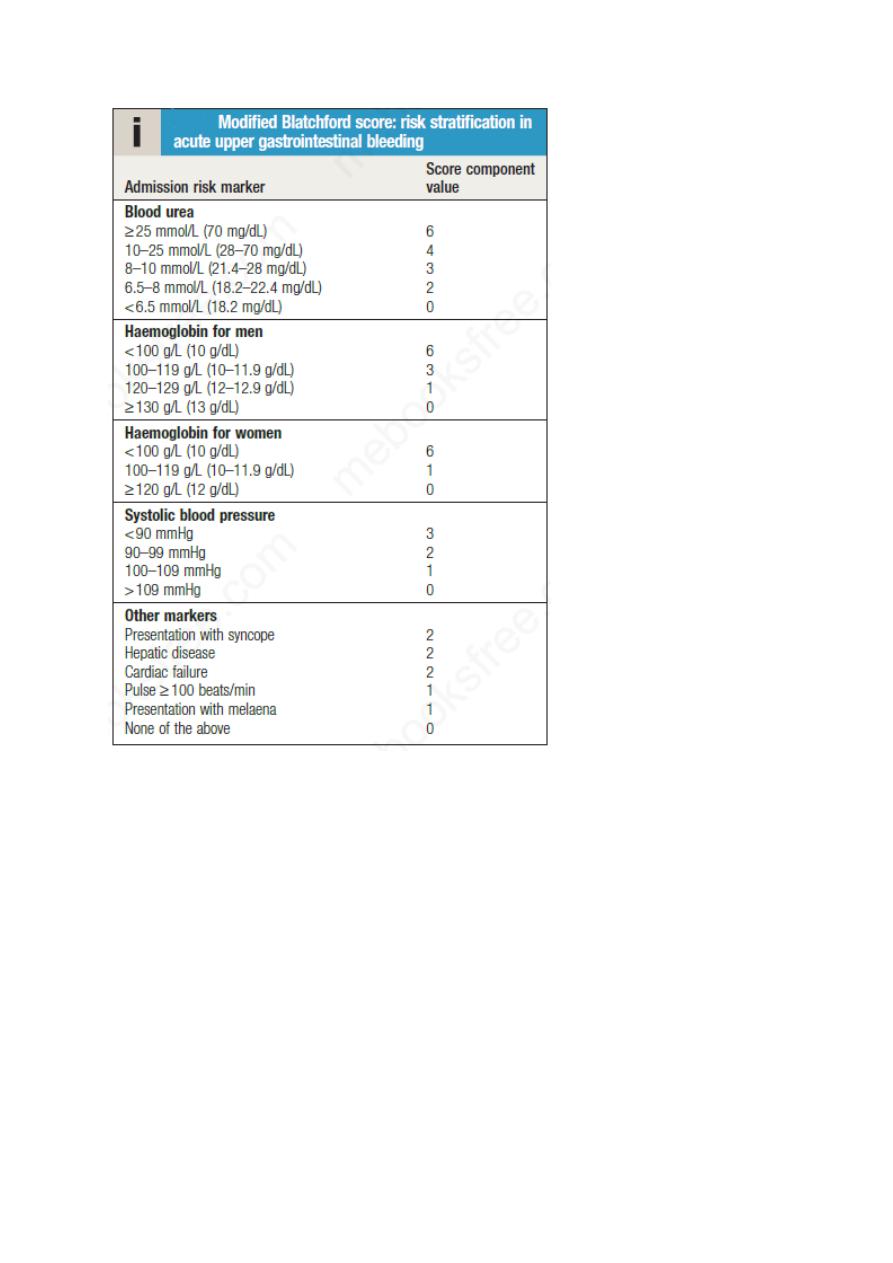

• Blatchford score: which can be calculated at the bedside. A score of 2 or less is

associated with a good prognosis, while progressively higher scores are

associated with poorer outcomes.

3. Basic investigations

• Full blood count. Chronic or subacute bleeding leads to anaemia but the

haemoglobin concentration may be normal after sudden, major bleeding until

haemodilution occurs. Thrombocytopenia may be a clue to the presence of

hypersplenism in chronic liver disease.

• Urea and electrolytes.

• Liver function tests.

• Prothrombin time.

• Cross-matching. At least 2 units of blood should be cross-matched if a

significant bleed is suspected.

4. Resuscitation

Intravenous crystalloid fluids should be given to raise the blood pressure, and

blood should be transfused when the patient is actively bleeding with low blood

pressure and tachycardia. Comorbidities should be managed as appropriate.

Patients with suspected chronic liver disease should receive broad-spectrum

antibiotics.

2

5. Oxygen: this should be given to all patients in shock.

6. Endoscopy

This should be carried out after adequate resuscitation, ideally within 24 hours,

and will yield a diagnosis in 80% of cases.

Treatment include:

A- ‘heater probe’

B- endoscopic clips,

C- usually combined with injection of dilute adrenaline (epinephrine) into the

bleeding point (‘dual therapy’).

D- A biologically inert haemostatic mineral powder (TC325, ‘haemospray’) can

be used as rescue therapy when standard therapy fails.

E- This may stop active bleeding and, combined with intravenous proton pump

inhibitor (PPI) therapy, may prevent re-bleeding.

3

F- Patients found to have bled from varices should be treated by band ligation;

if this fails,

G- Balloon tamponade.

H- transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS).

9. Eradication

Following treatment for ulcer bleeding, all patients should avoid non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and those who test positive for H. pylori

infection should receive eradication therapy. Successful eradication should be

confirmed by urea breath or faecal antigen testing.

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Causes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding

Severe acute

1. Diverticular disease

2. Angiodysplasia

3. Ischaemia

4. Meckel’s diverticulum

5. Inflammatory bowel disease (rarely)

Moderate, chronic/subacute

1. Fissure

2. Solitary rectal ulcer

3. Haemorrhoids

4. Inflammatory bowel disease

5. Angiodysplasia

6. Carcinoma

7. Large polyps

8. Radiation enteritis

Severe acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding

This presents with profuse red or maroon diarrhoea and with shock. Diverticular

disease is the most common cause and is often due to erosion of an artery within

the mouth of a diverticulum.

Subacute or chronic lower gastrointestinal bleeding

This can occur at all ages and is usually due to haemorrhoids or anal fissure.

Haemorrhoidal bleeding is bright red and occurs during or after defecation.

Proctoscopy can be used to make the diagnosis, but subjects who have altered

bowel habit and those who present over the age of 40 years should undergo

colonoscopy to exclude coexisting colorectal cancer. Anal fissure should be

suspected when fresh rectal bleeding and anal pain occur during defecation.

Ischemic gut injury

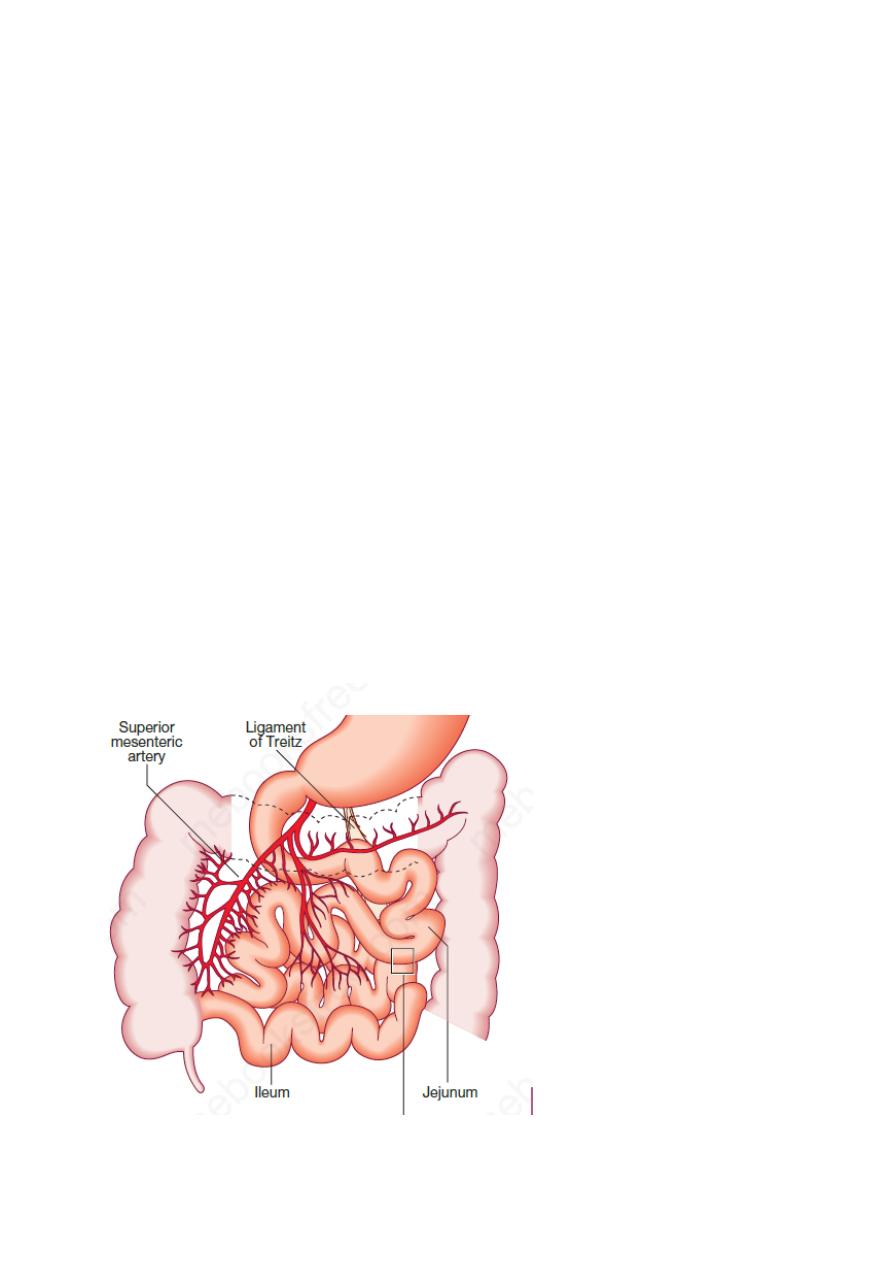

Acute small bowel ischaemia

Causes

4

1- An embolus from the heart ( specially in patient with AF)or aorta to the

superior mesenteric artery is responsible for 40–50% of cases.

2- thrombosis of underlying atheromatous disease for approximately 25%.

3- ischaemia due to hypotension complicating myocardial infarction, heart

failure, arrhythmias or sudden blood loss for approximately 25%

4- Vasculitis (rare)

Clinical feature: include diarrhea, lower GIT bleeding, and Almost all develop

abdominal pain that is more impressive than the physical findings.

Signs: In the early stages, the only physical signs may be a silent, distended

abdomen or diminished bowel sounds, with peritonitis developing only later.

Ix: Leucocytosis, metabolic acidosis, hyperphosphataemia and

hyperamylasaemia are typical. Plain abdominal X-rays show ‘thumb-printing’

due to mucosal oedema. Mesenteric or CT angiography reveals an occluded or

narrowed major artery with spasm of arterial arcades.

Investigations for underlying prothrombotic disorders should be performed.

Management:

Resuscitation, management of cardiac disease and intravenous antibiotic

therapy, followed by laparotomy and bowel resection, are key steps. If treatment

is instituted early, embolectomy and vascular reconstruction may salvage some

small bowel.

In patients at high surgical risk, thrombolysis may sometimes be effective. The

results of therapy depend on early intervention; patients treated late have a 75%

mortality rate.

Investigations for underlying prothrombotic disorders should be performed.

5

Acute colonic ischaemia:

The splenic flexure and descending colon have little collateral circulation and

lie in ‘watershed’ areas of arterial supply.

Causes

1- Arterial thromboembolism (main cause).

2- severe hypotension.

3- colonic volvulus.

4- strangulated hernia.

5- systemic vasculitis.

6- hypercoagulable states.

7- complication of abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery (where the inferior

mesenteric artery is ligated).

Clinical feature:

The patient is usually elderly and presents with sudden onset of cramping, left-

sided, lower abdominal pain and rectal bleeding. Symptoms usually resolve

spontaneously over 24–48 hours and healing occurs in 2 weeks.

Complication:

fibrous stricture or segment of colitis. A minority develop gangrene and

peritonitis.

Diagnosis: colonoscopy within 48 hour

Treatment: self-limit disease, Resection is required for peritonitis.

Chronic mesenteric ischaemia

This results from atherosclerotic stenosis of the coeliac axis, superior

mesenteric artery and inferior mesenteric artery. The typical presentation is with

dull but severe mid- or upper abdominal pain developing about 30 minutes after

eating. Weight loss is common because patients are reluctant to eat and some

experience diarrhoea. Physical examination shows

evidence of generalised arterial disease. An abdominal bruit is sometimes

audible but is non-specific. The diagnosis is made by mesenteric angiography.

Treatment is by vascular reconstruction or percutaneous angioplasty, if the

patient’s clinical condition permits. The condition is frequently complicated by

intestinal infarction, if left untreated.

With best wishes

6