Lec: 4

Dr. Mohammed Alhamdany

Acute pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis accounts for 3% of all cases of abdominal pain admitted to

hospital.

Pathophysiology

Acute pancreatitis occurs as a consequence of premature intracellular

trypsinogen activation, releasing proteases that digest the pancreas and

surrounding tissue.

Clinical features

1- The typical presentation is with severe, constant upper abdominal pain, of

increasing intensity over 15–60 minutes, which radiates to the back.

2- Nausea and vomiting are common.

3- There is marked epigastric tenderness, but in the early stages (and in contrast

to a perforated peptic ulcer), guarding and rebound tenderness are absent

because the inflammation is principally retroperitoneal.

4- Bowel sounds become quiet or absent as paralytic ileus develops.

5- In severe cases, the patient becomes hypoxic and develops hypovolaemic

shock with oliguria.

6- Discoloration of the flanks (GreyTurner’s sign) or the periumbilical region

(Cullen’s sign) is a feature of severe pancreatitis with haemorrhage.

Complication

Systemic

1- Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS): Increased vascular

permeability from cytokine, platelet-aggregating factor and kinin release.

2- Hypoxia: Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) due to microthrombi

in pulmonary vessels

3- Hyperglycaemia: Disruption of islets of Langerhans with altered insulin/

glucagon release

4- Hypocalcaemia: Sequestration of calcium in fat necrosis, fall in ionised

calcium.

5- Reduced serum albumin concentration: Increased capillary permeability

Pancreatic

1- Necrosis: Non-viable pancreatic tissue and peripancreatic tissue death;

frequently infected

2- Abscess: Circumscribed collection of pus close to the pancreas and

containing little or no pancreatic necrotic tissue

3- Pseudocyst: Disruption of pancreatic ducts

4- Pancreatic ascites or pleural effusion: Disruption of pancreatic ducts.

Gastrointestinal

1- Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Gastric or duodenal erosions.

2- Variceal haemorrhage: Splenic or portal vein thrombosis.

3- Erosion into colon: Erosion by pancreatic pseudocyst.

4- Duodenal obstruction: Compression by pancreatic mass.

5- Obstructive jaundice: Compression of common bile duct.

Causes of acute pancreatitis

Common (90% of cases)

1-

Gallstones

2-

Alcohol

3-

Idiopathic causes

4-

Post-ERCP

Rare

1-

Post-surgical (abdominal, cardiopulmonary bypass).

2-

Trauma.

3-

Drugs (azathioprine/mercaptopurine, thiazide diuretics, sodium valproate).

4-

Metabolic (hypercalcaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia).

5-

Pancreas divisum.

6-

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.

7-

Infection (mumps, Coxsackie virus).

8-

Renal failure.

Investigations

A- serum amylase or lipase: Amylase is efficiently excreted by the kidneys and

concentrations may have returned to normal if measured 24–48 hours after the

onset of pancreatitis. A persistently elevated serum amylase concentration

suggests pseudocyst formation. Peritoneal amylase concentrations are massively

elevated in pancreatic ascites.

Serum amylase concentrations are also elevated (but less so) in

1- intestinal ischaemia.

2- perforated peptic ulcer.

3- ruptured ovarian cyst.

4- while the salivary isoenzyme of amylase is elevated in parotitis.

If available, serum lipase measurements are preferable to amylase, as they have

greater diagnostic accuracy for acute pancreatitis.

B-Ultrasound scanning can confirm the diagnosis, although in the earlier stages

the gland may not be grossly swollen. The ultrasound scan is also useful

because it may show gallstones, biliary obstruction or pseudocyst formation.

C- CT for evidence of pancreatic swelling.

Contrast-enhanced pancreatic CT performed 6–10 days after admission can be

useful in assessing viability of the pancreas indicated if:

1- persisting organ failure.

2- sepsis

3- clinical deterioration is present.

since these features may indicate that pancreatic necrosis has occurred.

Necrotising pancreatitis is associated with decreased pancreatic enhancement on

CT, following intravenous injection of contrast material. The presence of gas

within necrotic material suggests infection and impending abscess formation, in

which case percutaneous aspiration of material for bacterial culture should be

carried out and appropriate antibiotics prescribed. Involvement of the colon,

blood vessels and other adjacent structures by the inflammatory process is best

seen by CT.

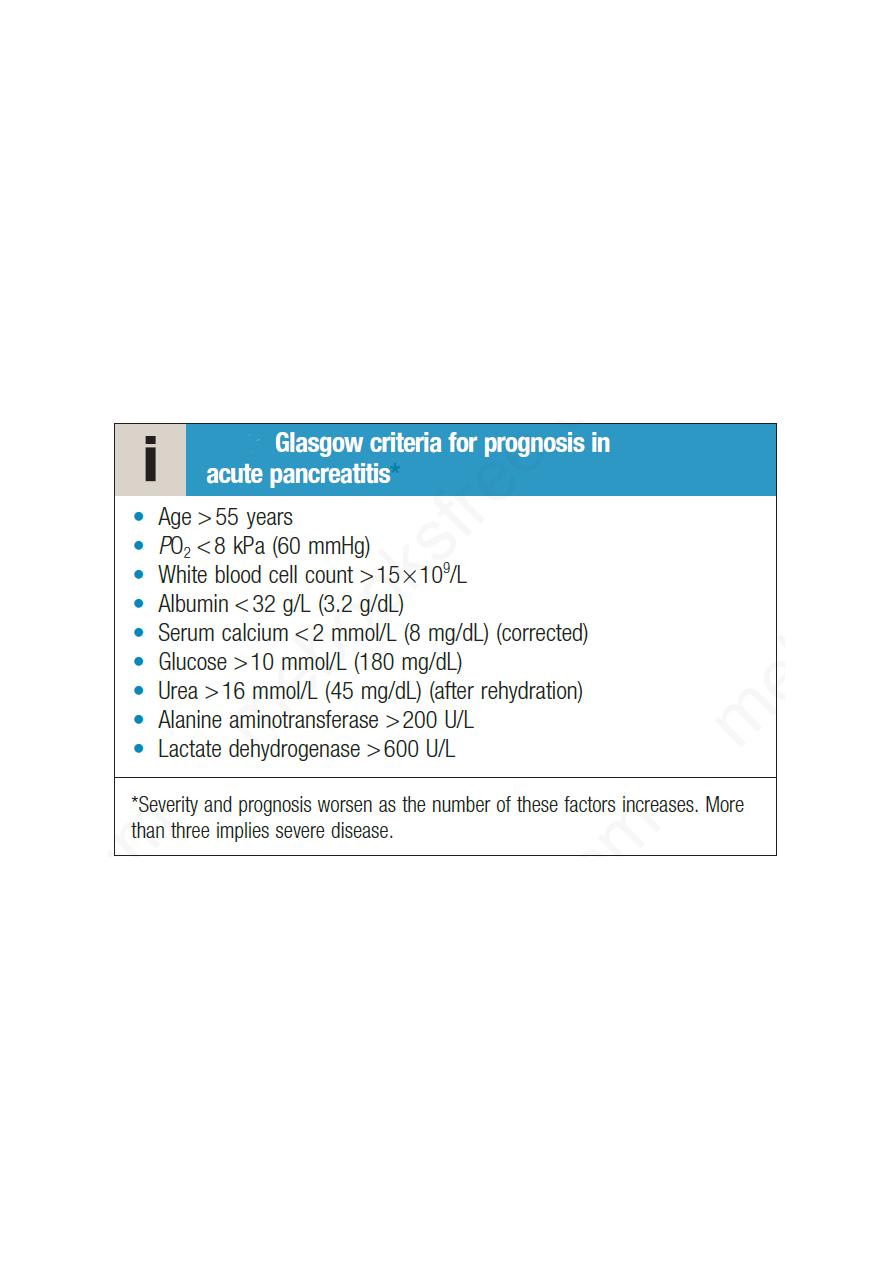

D- Certain investigations stratify the severity of acute pancreatitis and have

important prognostic value at the time of presentation. In addition, serial

assessment of CRP is a useful indicator of progress. A peak CRP of > 210 mg/L

in the first 4 days predicts severe acute pancreatitis with 80% accuracy. It is

worth noting that the serum amylase concentration has no prognostic value.

Management

Management comprises several related steps:

• establishing the diagnosis and disease severity

• Early resuscitation, according to whether the disease is mild or severe

• Detection and treatment of complications

• Treatment of the underlying cause.

The treatment includes:

1- Opiate analgesics should be given to treat pain.

2- Hypovolemia should be corrected using normal saline or other crystalloids.

3- All severe cases should be managed in a high-dependency or intensive care

unit. A central venous line and urinary catheter should be inserted to monitor

patients with shock.

4- Oxygen should be given to hypoxic patients, and those who develop systemic

inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) may require ventilatory support.

5- Hyperglycemia should be corrected using insulin.

6- Hypocalcaemia by intravenous calcium injection.

7- Nasogastric aspiration is required only if paralytic ileus is present. Enteral

feeding, if tolerated, should be started at an early stage in patients with severe

pancreatitis because they are in a severely catabolic state and need nutritional

support. Enteral feeding decreases endotoxaemia and so may reduce systemic

complications. Nasogastric feeding is just as effective as feeding by the

nasojejunal route.

8- Prophylaxis of thromboembolism with subcutaneous low-molecular-weight

heparin is also advisable.

9-The use of prophylactic, broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics to prevent

infection of pancreatic necrosis is not indicated, but infected necrosis is treated

with antibiotics that penetrate necrotic tissue, e.g. carbapenems or quinolones,

and metronidazole.

10- ERCP or surgery used for treatment of gallstone after stabilization.

Chronic pancreatitis

Causes of chronic pancreatitis:

1- Toxic–metabolic

• Alcohol

• Tobacco

• Hypercalcaemia

• Chronic kidney disease

2- Idiopathic

3- Genetic

4- Autoimmune

5- Recurrent and severe acute pancreatitis

6- Obstructive

• Ductal adenocarcinoma

• Pancreas divisum

• Sphincter of Oddi stenosis

(These can be memorised by the mnemonic ‘TIGARO’. Gallstones do not cause

chronic pancreatitis but may be observed as an incidental finding)

Clinical features

Chronic pancreatitis predominantly affects middle-aged alcoholic men. Almost

all present with abdominal pain. In 50%, this occurs as episodes of ‘acute

pancreatitis’, although each attack results in a degree of permanent pancreatic

damage. Relentless, slowly progressive chronic pain without acute

exacerbations affects 35% of patients, while the remainder have no pain but

present with diarrhoea.

Weight loss is common and results from a combination of :

1- anorexia,

2- avoidance of food because of post-prandial pain,

3- malabsorption

4- diabetes.

Steatorrhoea occurs when more than 90% of the exocrine tissue has been

destroyed; protein malabsorption develops only in the most advanced cases.

Overall, 30% of patients have (secondary) diabetes but this figure rises to 70%

in those with chronic calcific pancreatitis.

Physical examination

Reveals a thin, malnourished patient with epigastric tenderness. Skin

pigmentation over the abdomen and back is common and results from chronic

use of a hot water bottle (erythema ab igne). Many patients have features of

other alcohol- and smoking related diseases.

Complications

of chronic pancreatitis

•

Pseudocysts and pancreatic ascites, which occur in both acute and chronic

pancreatitis

•

Obstructive jaundice due to benign stricture of the common bile duct as it

passes through the diseased pancreas

•

Duodenal stenosis

•

Portal or splenic vein thrombosis leading to segmental portal hypertension and

gastric varices

•

Peptic ulcer

Investigations in chronic pancreatitis

A- Tests to establish the diagnosis

•

Ultrasound

•

Computed tomography (may show atrophy, calcification or ductal dilatation)

•

Abdominal X-ray (may show calcification)

•

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

•

Endoscopic ultrasound

B- Tests to define pancreatic function

•

Collection of pure pancreatic juice after secretin injection (gold standard but

invasive and seldom used)

•

Pancreolauryl test

•

Faecal pancreatic elastase

C- Tests to demonstrate anatomy prior to surgery

•

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

Management

1- Alcohol misuse: Alcohol avoidance is crucial in halting progression of the

disease and reducing pain.

2- Pain relief

A range of analgesic drugs, particularly NSAIDs, are valuable but the severe

and unremitting nature of the pain often leads to opiate use with the risk of

addiction. Analgesics, such as pregabalin and tricyclic antidepressants at a low

dose, may be effective. Oral pancreatic enzyme supplements suppress

pancreatic secretion and their regular use reduces analgesic consumption in

some patients. Patients who are abstinent from alcohol and who have severe

chronic pain that is resistant to conservative measures should be considered for

surgical or endoscopic pancreatic therapy.

Many endoscopic and surgical intervention uses to reduce pain in chronic

pancreatitis, such as Dilatation or stenting of pancreatic duct strictures, and

surgical partial pancreatic resection, preserving the duodenum.

Coeliac plexus neurolysis sometimes produces long-lasting pain relief, and

patient who not respond and MRCP does not show a surgically or

endoscopically correctable abnormality,surgical total pancreatectomy can be

used. Unfortunately, even after this operation, some continue to experience pain.

Moreover, the procedure causes diabetes, which may be difficult to control, with

a high risk of hypoglycaemia (since both insulin and glucagon are absent) and

significant morbidity and mortality.

3- Malabsorption

This is treated by dietary fat restriction (with supplementary medium-chain

triglyceride therapy in malnourished patients) and oral pancreatic enzyme

supplements. A PPI is added to optimize duodenal pH for pancreatic enzyme

activity.

4- Management of complications

Surgical or endoscopic therapy may be necessary for the management of

pseudocysts, pancreatic ascites, common bile duct or duodenal stricture and the

consequences of portal hypertension. Many patients with chronic pancreatitis

also require treatment for other alcohol- and smoking related diseases and for

the consequences of self-neglect and malnutrition.

With best wishes