Vermiform appendix

ا د ﻣﮭﻧد اﻟﺷﻼه

Understanding applied anatomy , micro anatomy

and pathophysiology

Describe the clinical features, investigations and

principles of management of diseases of Appendix

including appendicitis and its complications.

Learning objectives

The vermiform appendix is importance in surgery due to its

propensity for inflammation, which results in the clinical syndrome

known as ‘acute appendicitis’.

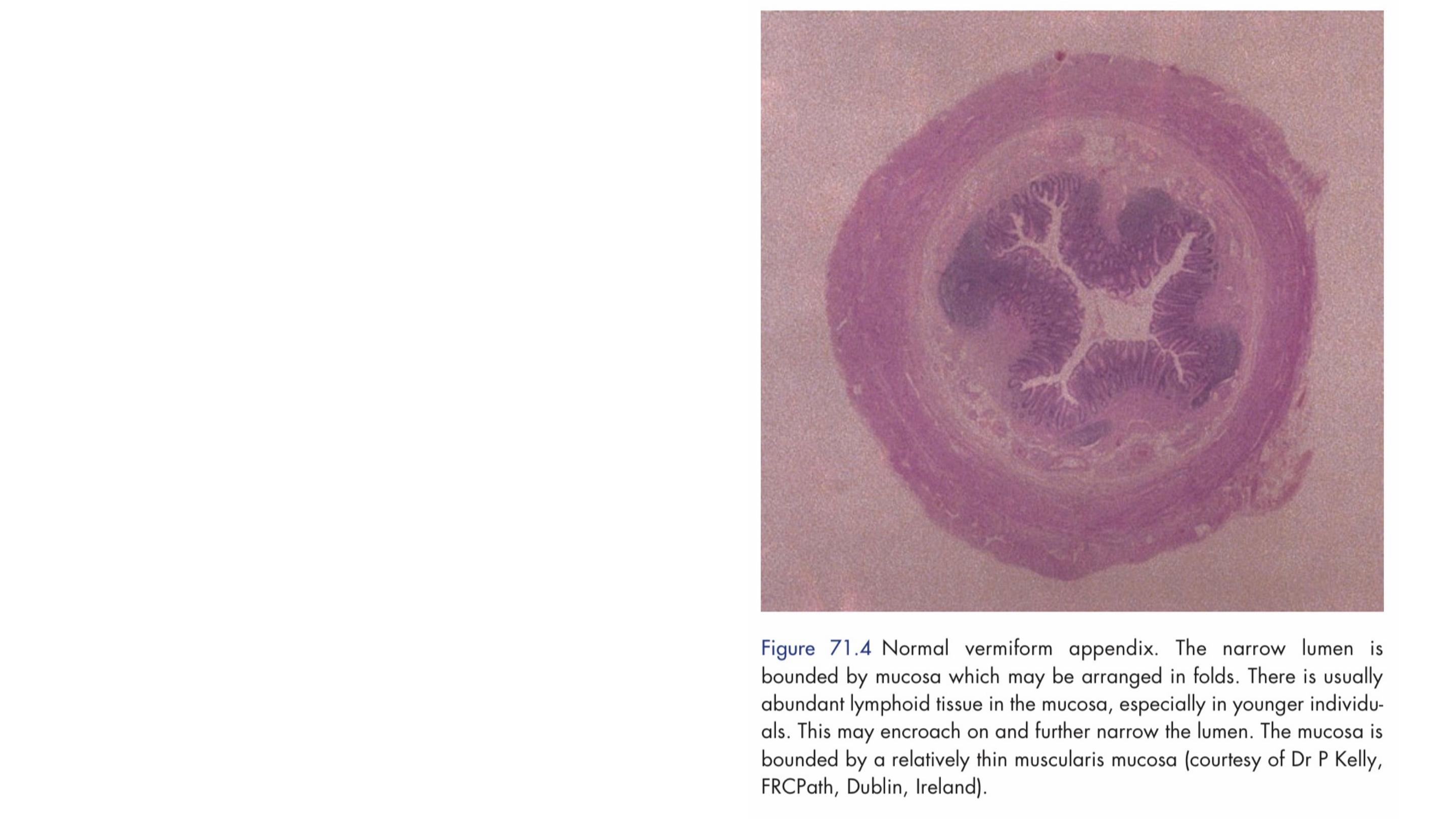

The vermiform appendix is a blind muscular tube with mucosal,

submucosal, muscular and serosal layers.

Acute appendicitis is the most common cause of an ‘acute abdomen’ in

young adults.

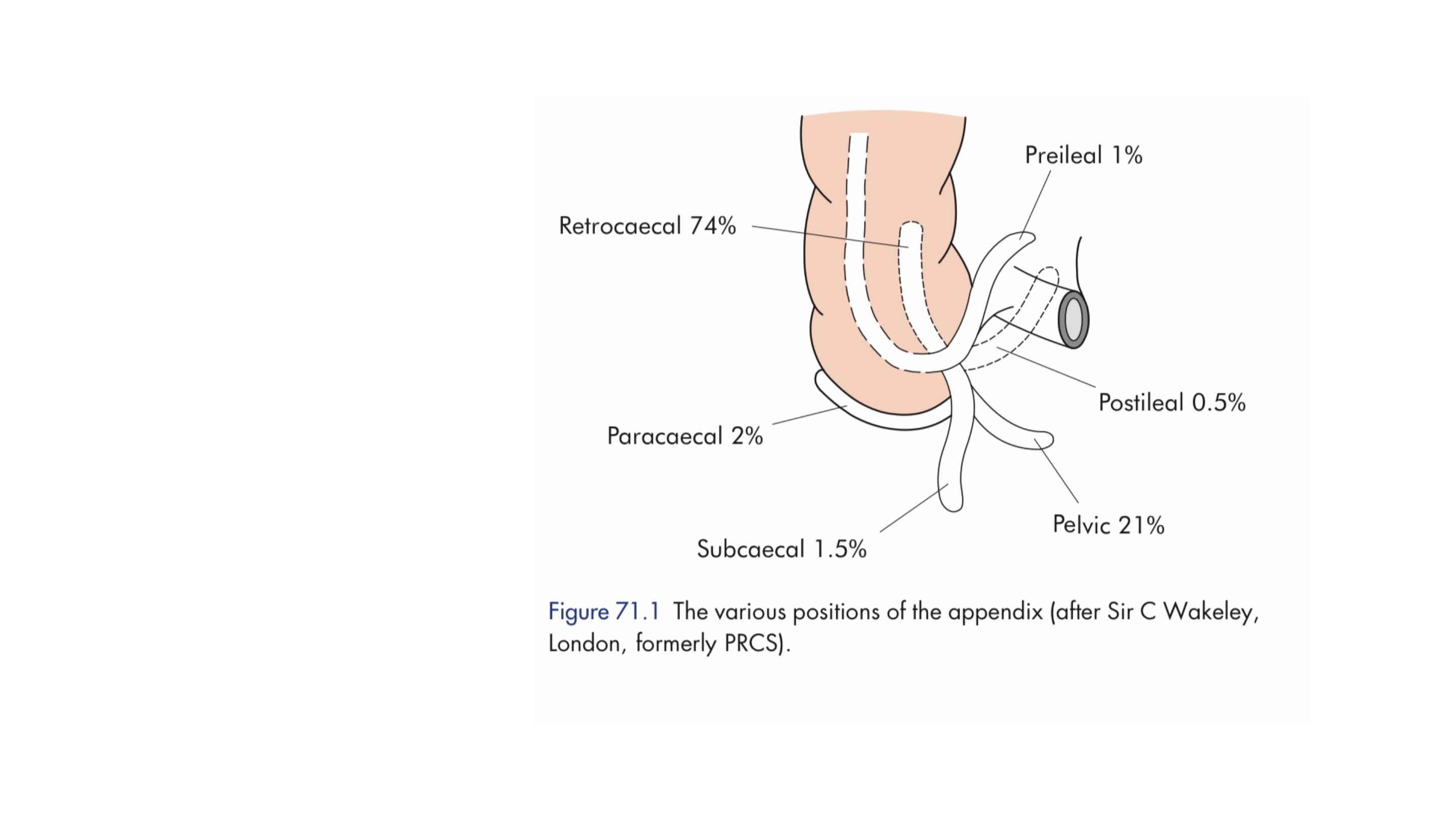

Applied anatomy

The position of the base of the

appendix is constant. It is found

at the confluence of the three

taeniae coli, an anatomical fact

often used to find the appendix

during an operation for acute

appendicitis.

Histologically the submucosa of

the appendix is rich in lymphoid

follicles. In the base of the

appendicular crypts argentaffin

(Kulschitsky) cells, the source of

carcinoid tumours, are present.

It’s lined by columnar cell intestinal

mucosa of colonic type.

Microscopic anatomy

The pathophysiologic process leading to acute appendicitis was initially

described by Dr. Reginald Fitz in 1886, where appendicitis was described as

a process that began with appendiceal luminal obstruction that led to

secondary bacterial infection, ischemia, necrosis, and perforation.

Causes result in lumen obstruction :

1. Hypertrophied lymphoid tissue

2. Fecalith

3. Foreign body

4. Parasite

5. Tumor (carcinoid)

Natural history of acute appendicitis

Once obstruction occurs, Oedema and mucosal ulceration

develop with bacterial translocation to the submucosa.

Resolution may occur at this point either spontaneously or

in response to antibiotic therapy.

If the condition progresses, further distension of the

appendix may cause venous obstruction and ischaemia of

the appendix wall.

Finally, ischaemic necrosis of the appendix wall produces

gangrenous appendicitis, with free bacterial contamination

of the peritoneal cavity.

Alternatively, the greater omentum and loops of

small bowel become adherent to the inflamed

appendix, walling off the spread of peritoneal

contamination, and resulting in a phlegmonous

mass or paracaecal abscess.

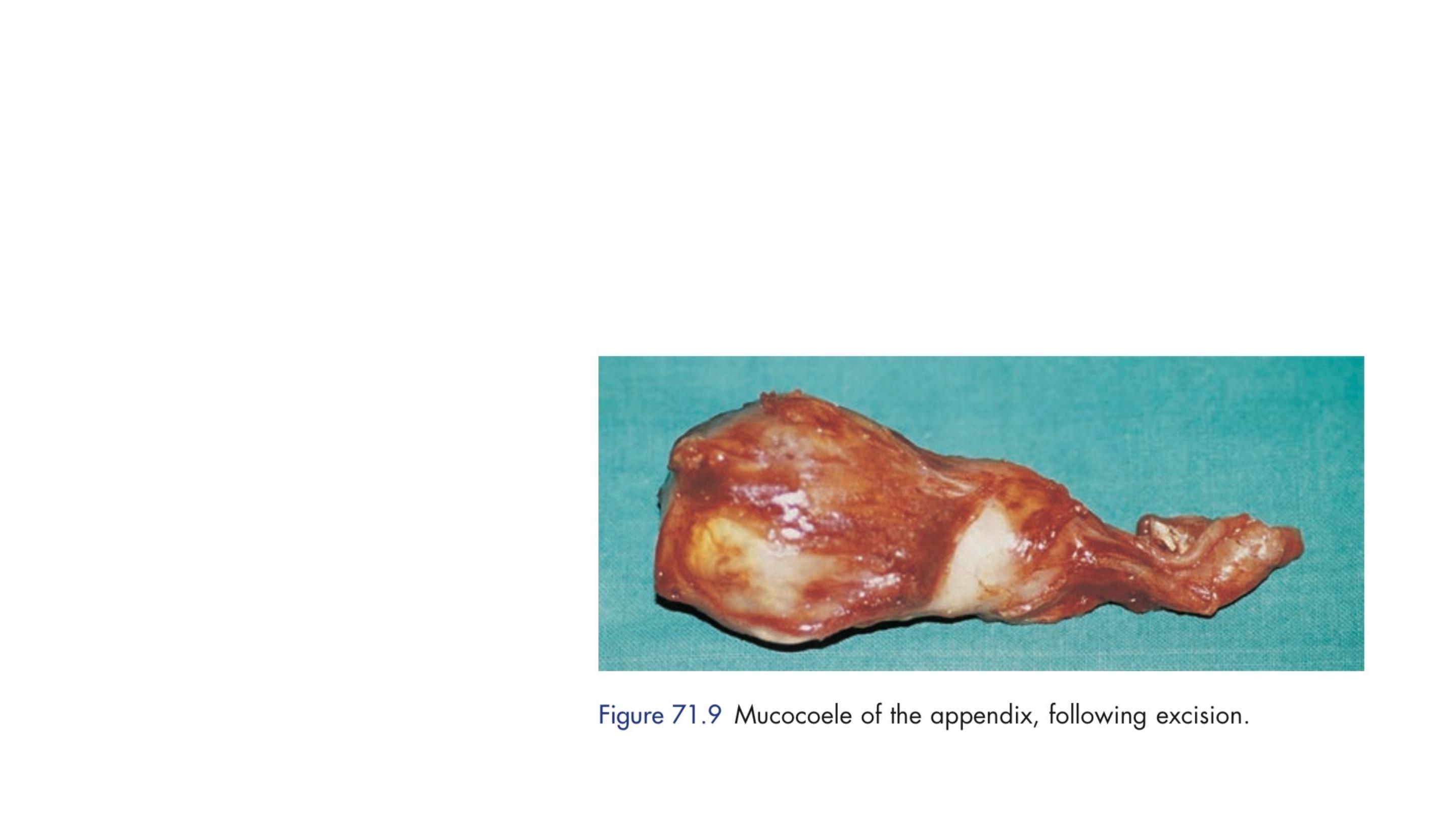

Rarely, appendiceal inflammation resolves,

leaving a distended mucus-filled organ termed a

‘mucocoele’ of the appendix.

Typically, two clinical syndromes of acute appendicitis can be

discerned, acute catarrhal (non-obstructive) appendicitis and acute

obstructive appendicitis, the latter characterised by a more acute

course.

Risk factors for perforation of the appendix

■ Extremes of age

■ Immunosuppression

■ Diabetes mellitus

■ Faecolith obstruction

■ Pelvic appendix

■ Previous abdominal surgery

Symptoms of appendicitis

■ Periumbilical colic

■

Pain shifting to the right iliac fossa

■

Anorexia

■ Nausea

Clinical signs in appendicitis

■ Pyrexia

■ Localised tenderness in the right iliac fossa

■ Muscle guarding

■ Rebound tenderness

■ Pointing sign

■ Rovsing’s sign

■ Psoas sign

■

Obturator sign

■

Cutaneous hyperaesthesia

Retrocaecal

Rigidity is often absent, and even application of deep pressure may

fail to elicit tenderness

However, deep tenderness is often present in the loin, and rigidity of

the quadratus lumborum may be in evidence.

Psoas spasm, due to the inflamed appendix being in contact with

that muscle, may be sufficient to cause flexion of the hip joint.

Hyperextension of the hip joint may induce abdominal pain when the

degree of psoas spasm is insufficient to cause flexion of the hip.

Special features, according to position of the appendix

Pelvic

Occasionally, early diarrhoea results from an inflamed appendix being in contact with

the rectum.

When the appendix lies entirely within the pelvis, there is usually complete absence of

abdominal rigidity, and often tenderness over McBurney’s point is also lacking.

In some instances, deep tenderness can be made out just above and to the right of

the symphysis pubis.

In either event, a rectal examination reveals tenderness in the rectovesical pouch or the

pouch of Douglas, especially on the right side.

Spasm of the psoas and obturator internus muscles may be present when the

appendix is in this position.

An inflamed appendix in contact with the bladder may cause frequency of micturition.

This is more common in children.

Postileal

It presents the greatest difficulty in diagnosis because the pain may not shift,

diarrhoea is a feature and marked retching may occur.

Tenderness, if any, is ill defined, although it may be present immediately to

the right of the umbilicus.

Differential diagnosis

Acute gastroenteritis

Mesenteric lymphadenitis

Meckel’s diverticulitis

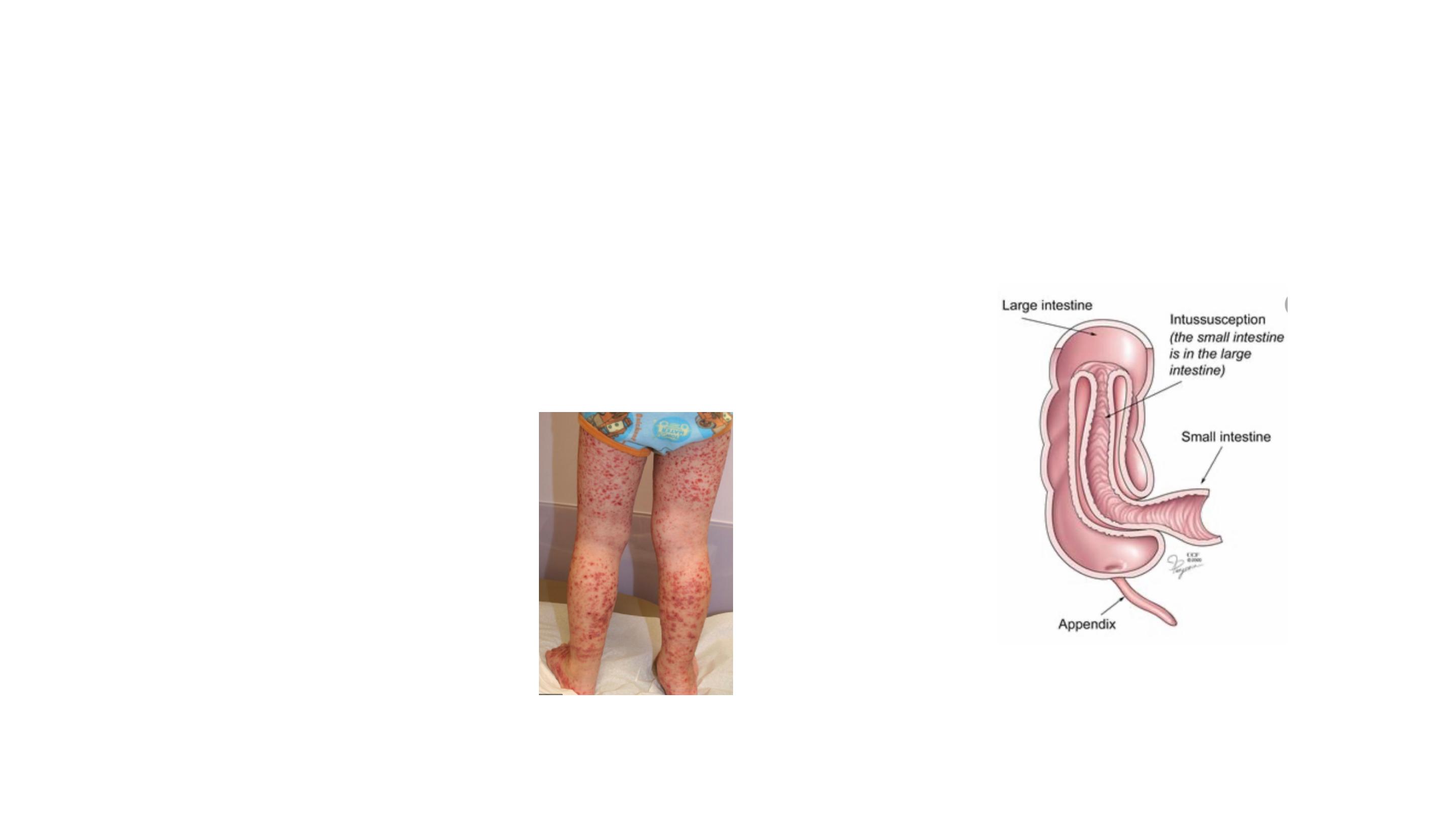

Intussusception

Henoch–Schönlein purpura

Lobar pneumonia and pleurisy

Regional enteritis

Ureteric colic

Right-sided acute pyelonephritis

Perforated peptic ulcer

Differential Diagnosis in Adult

Torsion of testis

Pancreatitis

Rectus sheath haematoma

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

Mittelschmerz

Endometriosis

Pyelonephritis

Differential Diagnosis in adult female

Torsion or haemorrhage of an ovarian cyst

Ectopic pregnancy.

Diverticulitis

Intestinal obstruction

Colonic carcinoma

Differential Diagnosis in elderly

Torsion appendix epiploicae

Mesenteric infarction

Leaking aortic aneurysm

Preoperative investigations in appendicitis

■ Routine

Full blood count

Urinalysis

■ Selective

Pregnancy test

Urea and electrolytes

Supine abdominal radiograph

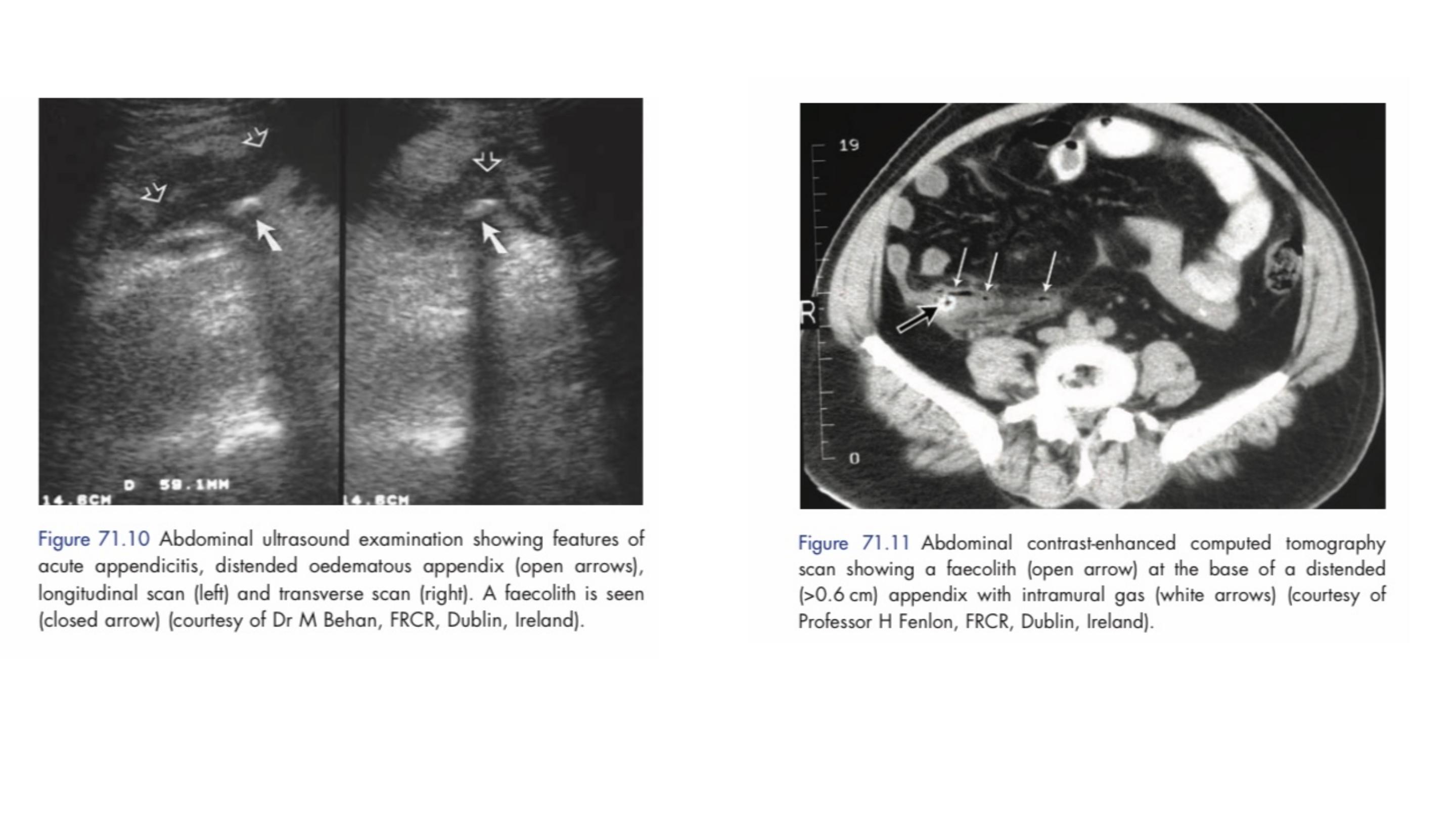

Ultrasound of the abdomen/pelvis

Contrast-enhanced abdomen and pelvic computed tomography scan

The diagnosis of acute appendicitis is essentially clinical;

however, a decision to operate based on clinical suspicion

alone can lead to the removal of a normal appendix in 15–

30 per cent of cases.

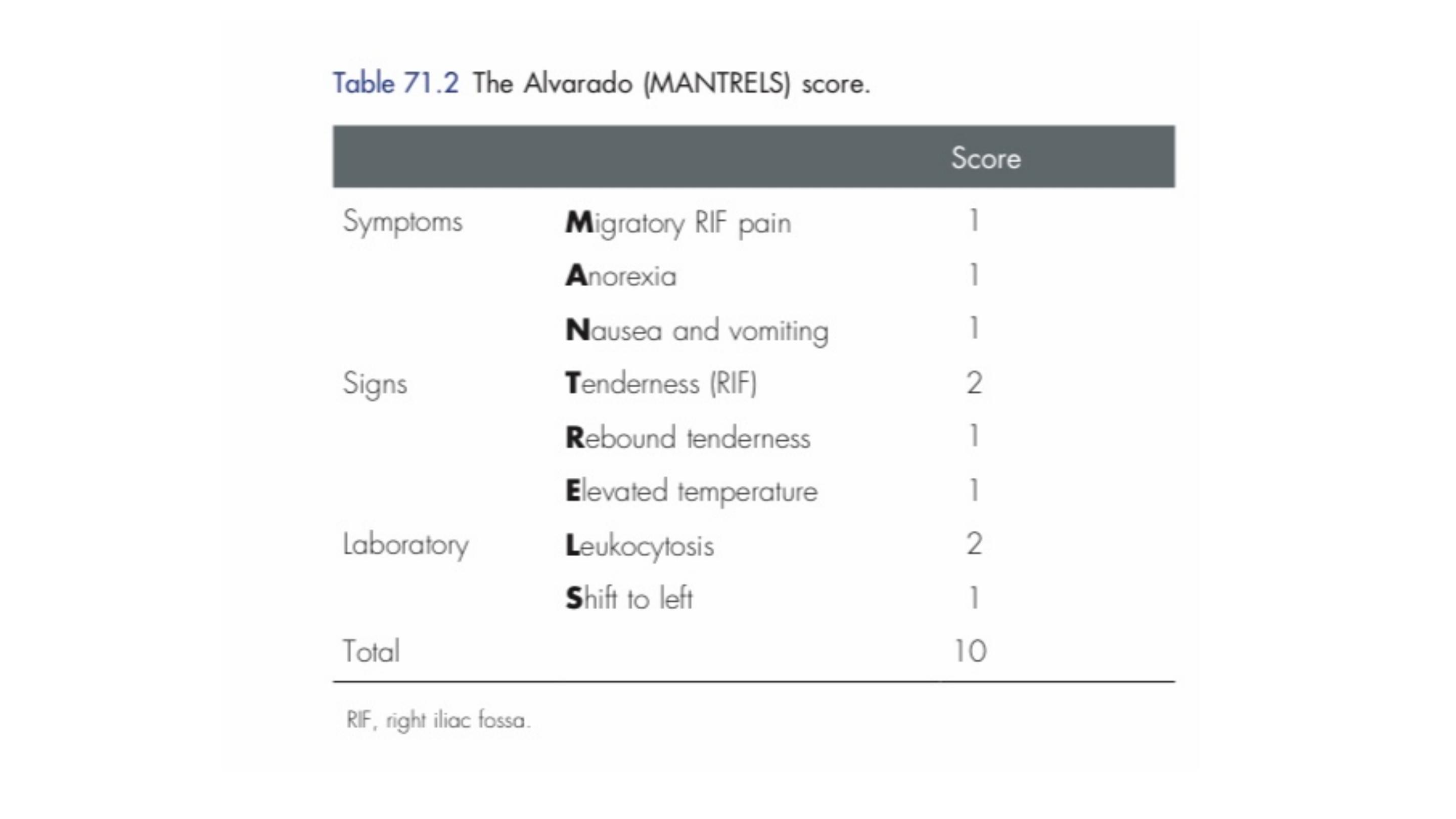

A score of 7 or more is strongly predictive of acute

appendicitis.

In patients with an equivocal score (5–6), abdominal

ultrasound or contrast-enhanced CT examination further

reduces the rate of negative appendicectomy.

What are the traditional treatment for acute

appendicitis ?

There is an emerging body of literature to support a

trial of conservative management in patients with

uncomplicated (absence of appendicolith, perforation or

abscess) appendicitis.

Treatment is bowel rest and intravenous antibiotics, usually

metranidazole and third-generation cephalosporin.

The available data indicate successful outcomes in 80–90 per cent of

patients, however there is an approximately 15 per cent recurrence

rate within one year.

This approach should be considered in patients with high operative

risk (multiple comorbidities).

Conservative management

Recommendation is to use laparoscopy and LA in patients with

suspected appendicitis unless laparoscopy itself is contraindicated or

not feasible. Especially young female, obese, and employed patients

seem to benefit from LA.

Thank you for your attention