Professor Dr. Mohanned Alshalah

Intestinal obstruction

Year 4 / Course 2 /lecture 1

To understand:

• The pathophysiology of dynamic and adynamic intestinal obstruction

• The cardinal features on history and examination

•

The causes of small and large bowel obstruction

•

The indications for surgery and other treatment options in bowel

obstruction

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

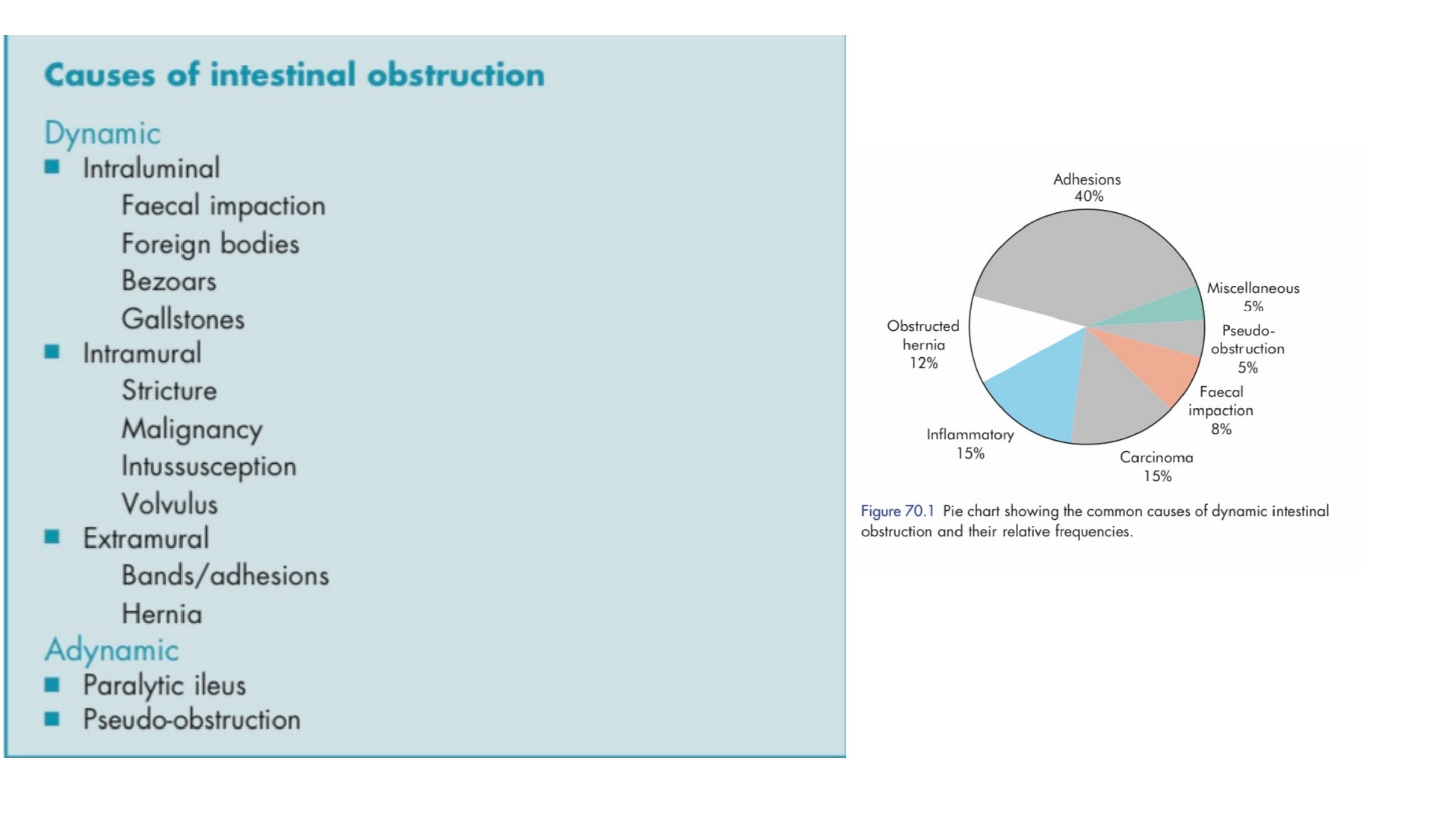

Intestinal obstruction may be classified into two types:

Dynamic, in which peristalsis is working against a mechanical

obstruction. It may occur in an acute or a chronic form

Adynamic, in which there is no mechanical obstruction; peristalsis is

absent or inadequate (e.g. paralytic ileus or pseudo-obstruction).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

In dynamic (mechanical) obstruction the bowel proximal to the

obstruction dilates and the bowel below the obstruction exhibits normal

peristalsis and absorption until it becomes empty and collapses.

The distension proximal to an obstruction is caused by two factors:

• Gas: there is a significant overgrowth of both aerobic and anaerobic

organisms, resulting in considerable gas production. Following the

reabsorption of oxygen and carbon dioxide, the majority is made up of

nitrogen (90 per cent) and hydrogen sulphide.

• Fluid: this is made up of the various digestive juices.

Dehydration and electrolyte loss are therefore due to:

Reduced oral intake;

Defective intestinal absorption;

Losses as a result of vomiting;

Sequestration in the bowel lumen;

Transudation of fluid into the peritoneal cavity.

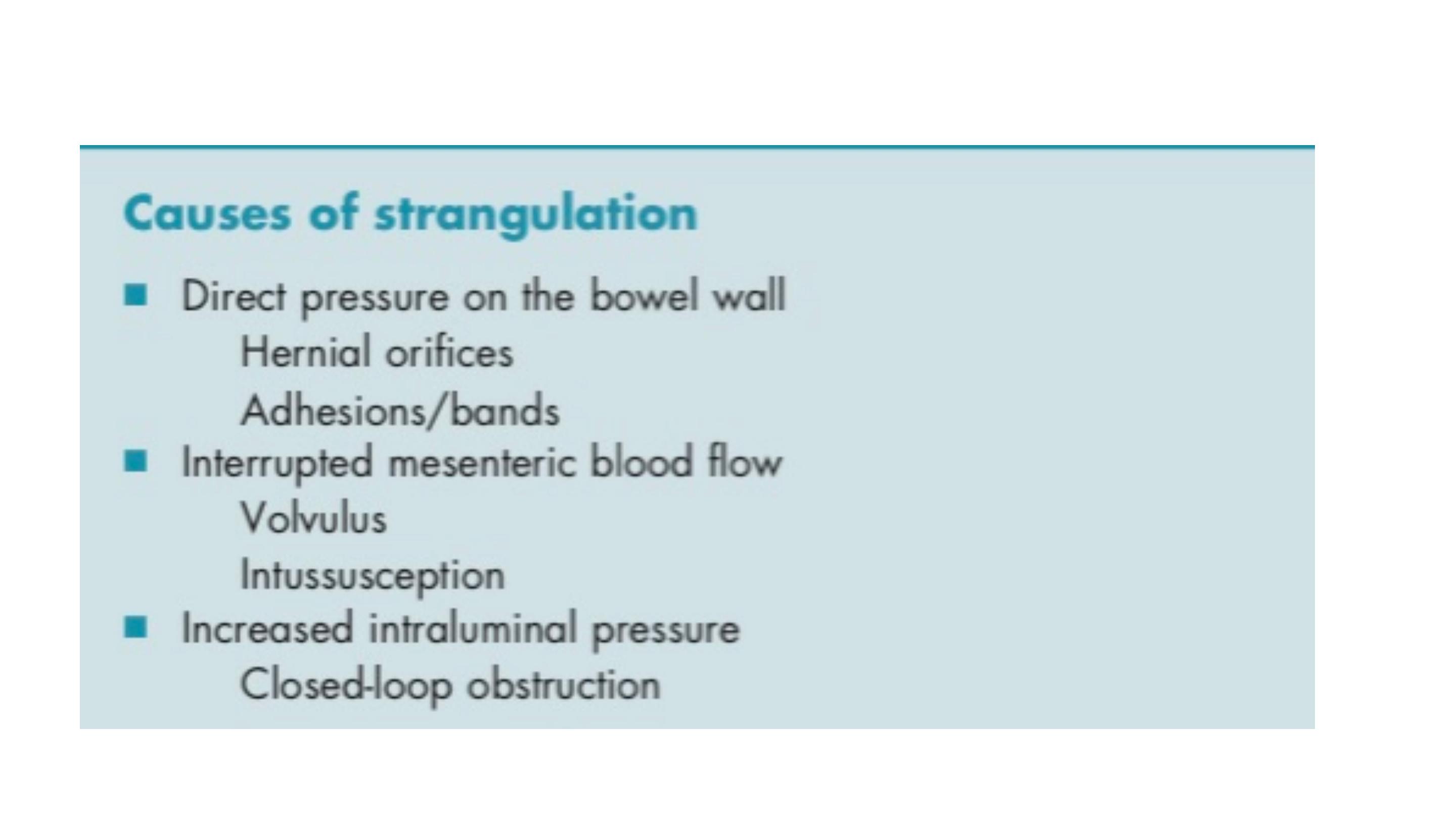

When strangulation occurs, the blood supply is compromised and the

bowel becomes ischaemic

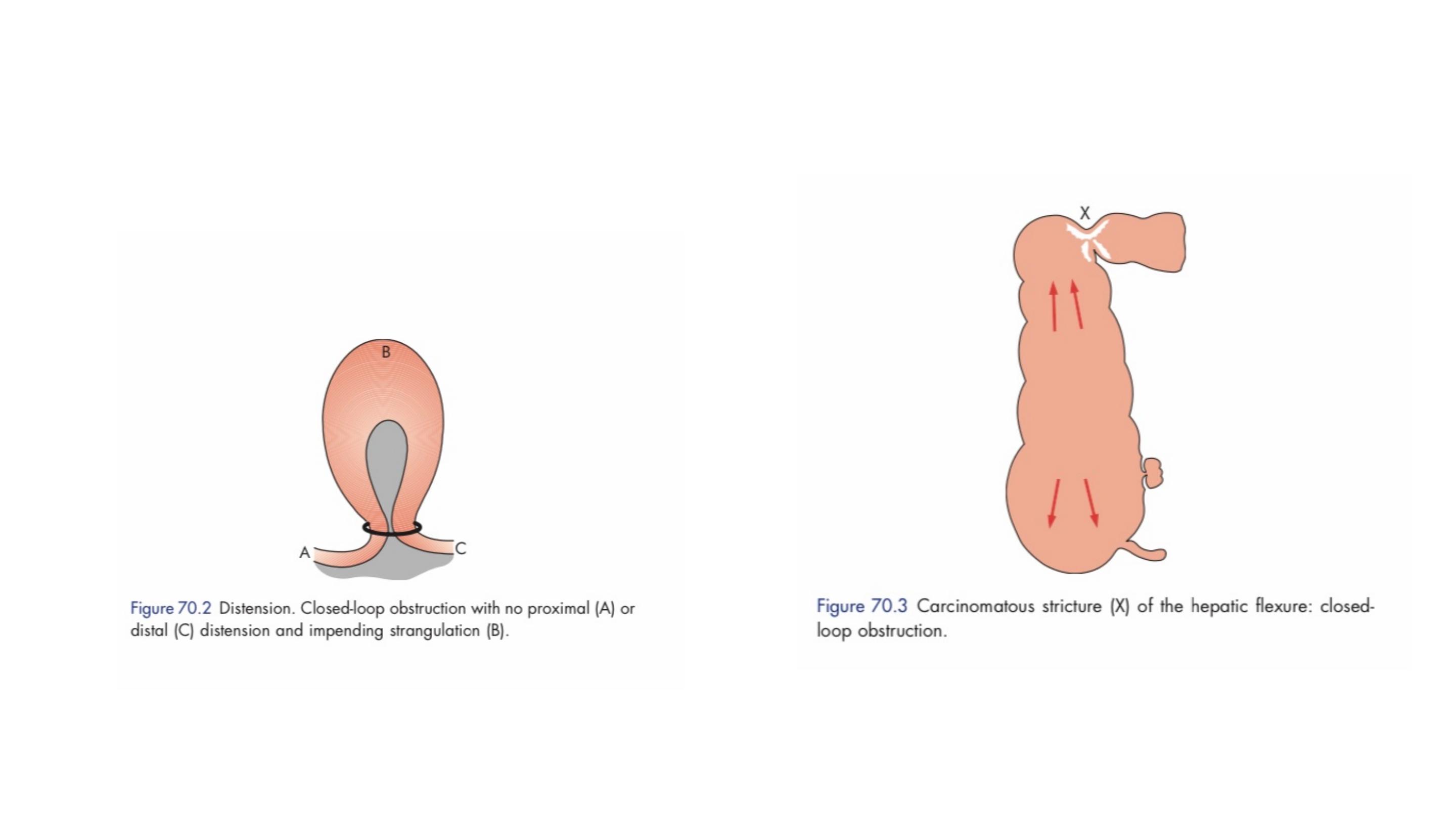

Closed-loop obstruction: This occurs when the bowel is obstructed at

both the proximal and distal points.

CLINICAL FEATURES OF INTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION

Cardinal clinical features of acute obstruction

■ Abdominal pain

■ Distension

■ Vomiting

■ Absolute constipation

Dehydration

results in dry skin and tongue, poor venous filling and sunken

eyes with oliguria. The blood urea level and haematocrit rise, giving a secondary

polycythaemia.

Hypokalaemia

is not a common feature in simple mechanical

obstruction. An increase in serum potassium, amylase or lactate

dehydrogenase may be associated with the presence of strangulation

Pyrexia

in the presence of obstruction is rare and may indicate:

• the onset of ischaemia;

• intestinal perforation;

• inflammation or abscess associated with the obstructing disease.

Hypothermia

indicates septicaemic shock

Features of obstruction

■ In high small bowel obstruction, vomiting occurs early, is profuse and causes

rapid dehydration. Distension is minimal with little evidence of dilated small

bowel loops on abdominal radiography

■ In low small bowel obstruction, pain is predominant with central distension.

Vomiting is delayed. Multiple dilated small bowel loops are seen on radiography

■ In large bowel obstruction, distension and pronounced. Pain is less severe

and vomiting and dehydration are later features. The colon proximal to the

obstruction is distended on abdominal radiography. The small bowel will be

dilated if the ileocaecal valve is incompetent

Absolute constipation doesn’t present in intestinal obstruction in :

• Richter’s hernia;

• gallstone ileus;

• mesenteric vascular occlusion;

• functional obstruction associated with pelvic abscess;

• all cases of partial obstruction (in which diarrhoea may occur).

Abdominal tenderness

Localised tenderness indicates impending or established ischaemia.

The development of peritonism or peritonitis indicates impending or overt

infarction and/or perforation.

In cases of large bowel obstruction, it is important to elicit these findings in

the right iliac fossa as the caecum is most vulnerable to ischaemia.

Bowel sounds

High-pitched bowel sounds are present in the vast majority of

patients with intestinal obstruction.

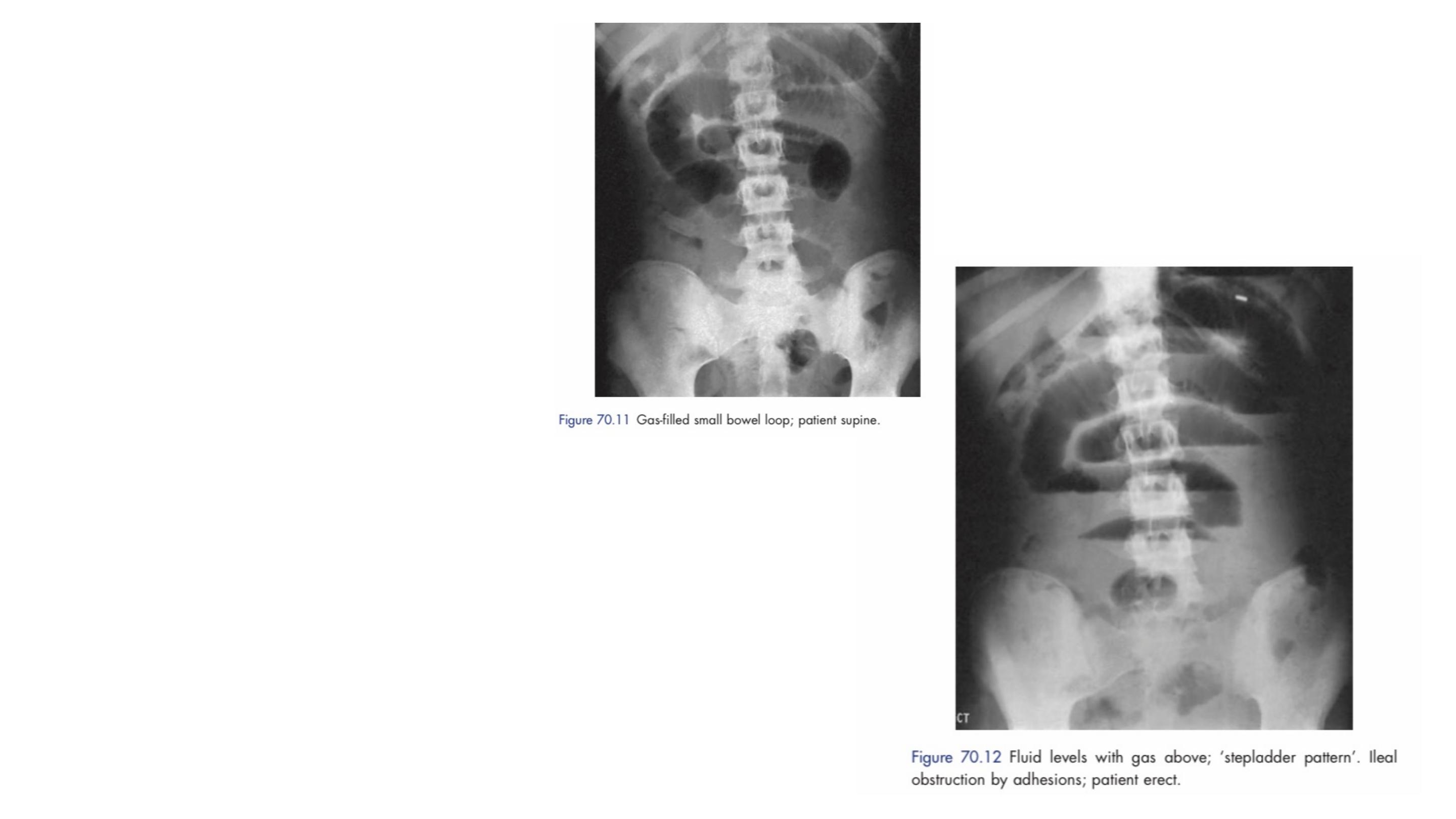

Radiological diagnosis is

based on a supine abdominal

film.

An erect film may subsequently

be requested when further

doubt exists.

In the small bowel, the number of fluid levels

is directly proportional to the degree of

obstruction

■ The obstructed small bowel is characterised by straight segments that are

generally central and lie transversely. No/minimal gas is seen in the colon

■ The jejunum is characterised by its valvulae conniventes, which completely

pass across the width of the bowel and are regularly spaced, giving a

‘concertina’ or ladder effect

■ Ileum – the distal ileum is featureless

■ Caecum – a distended caecum is shown by a rounded gas shadow in the

right iliac fossa

■ Large bowel, except for the caecum, shows haustral folds, which, unlike

valvulae conniventes, are spaced irregularly, do not cross the whole diameter of

the bowel and do not have indentations placed opposite one another

Radiological features of obstruction (on plain x-ray)

Branco BC, Barmparas G, Schnuriger B et al. Systematic review and

meta-analyis of the diagnostic and therapeutic role of water-soluble

contrast agent in adhesive small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg 2010;

In patients without evidence of strangulation, there is a role for other

imaging modalities.

The CT scan is now used very widely to investigate all forms of intestinal

obstruction.

It is highly accurate and its only limitations are in diagnosing ischaemia.

It is important to remember that even with the best imaging techniques, the

diagnosis of strangulation remains a clinical one.

Treatment of acute intestinal obstruction

■ Gastrointestinal drainage via a nasogastric tube

■ Fluid and electrolyte replacement

■ Relief of obstruction

Surgical treatment is necessary for most cases of intestinal obstruction

but should be delayed until resuscitation is complete, provided there is

no sign of strangulation or evidence of closed-loop obstruction

The timing of surgical intervention is dependent on the clinical picture.

Indications for early surgical intervention

■ Obstructed external hernia

■ Clinical features suspicious of intestinal strangulation

■ Obstruction in a ‘virgin’ abdomen

The classic clinical advice that ‘

the sun should not both rise and set

’

on a case of unrelieved acute intestinal obstruction’

If there is complete obstruction, but no evidence of intestinal ischaemia, it

is reasonable to defer surgery until the patient has been adequately

resuscitated.

Where obstruction is likely to be secondary to adhesions, conservative management

may be continued for up to 72 hours in the hope of spontaneous resolution.

• the site of obstruction;

• the nature of the obstruction;

• the viability of the gut.

Assessment is directed to:

The type of surgical procedure required will depend upon the cause of

obstruction – division of adhesions (enterolysis), excision, bypass or

proximal decompression.

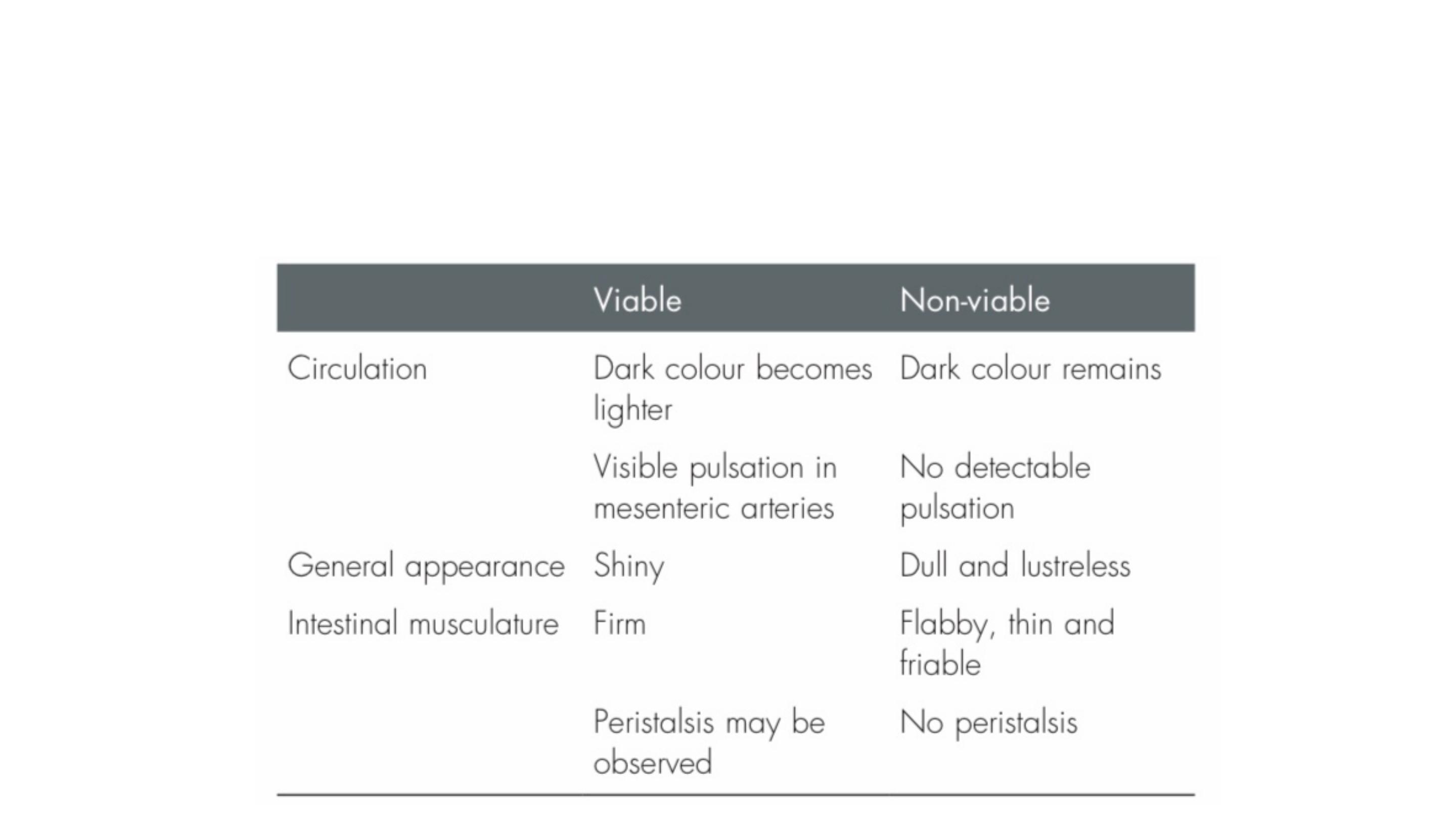

Following relief of obstruction, the viability of the involved

bowel should be carefully assessed

If in doubt, the bowel should be wrapped in hot packs for 10

minutes with increased oxygenation and then reassessed.

If at the end of this period, there is still uncertainty about gut viability,

the gut should be resected if this does not result in short bowel

syndrome.

If the patient is septic such that they require inotropic therapy or would

require postoperative level 3 intensive care treatment following

resection, consideration should be given to raising both ends of the

bowel as stomas.

This is not only safe, but also allows regular assessment of the bowel.

Intestinal ischaemia/reperfusion injury has been described following reperfusion

of ischaemic bowel with remote lung injury resulting from the release of

inflammatory mediators.

For example, if there is a volvulus with established infarction, detorsion should

be avoided until the affected mesentery has been clamped and thus reperfusion

injury prevented.

The end