ا د مهند الشاله

Intestinal obstruction

Lecture 2

■ Initially treat conservatively provided there are no signs of strangulation;

should rarely continue conservative treatment for longer than 72 hours

■ At operation, divide only the causative adhesion(s) and limit dissection

■ Repair serosal tears; invaginate (or resect) areas of doubtful viability

■ Laparoscopic adhesiolysis may be considered in highly selected cases of

small bowel obstruction and should only undertaken by surgeon with advanced

laparoscopic skills

Treatment of adhesive obstruction

Large bowel obstruction is usually caused by an underlying carcinoma or

occasionally diverticular disease, and presents in an acute or chronic form.

The condition of pseudo-obstruction should always be considered and excluded

by a limited contrast study or CT scan to confirm organic obstruction.

After full resuscitation, the abdomen should be opened through a midline

incision.

TREATMENT OF ACUTE LARGE BOWEL OBSTRUCTION

Identification of a collapsed distal segment of the large bowel and its sequential

proximal assessment will readily lead to identification of the cause.

Distension of the caecum will confirm large bowel involvement.

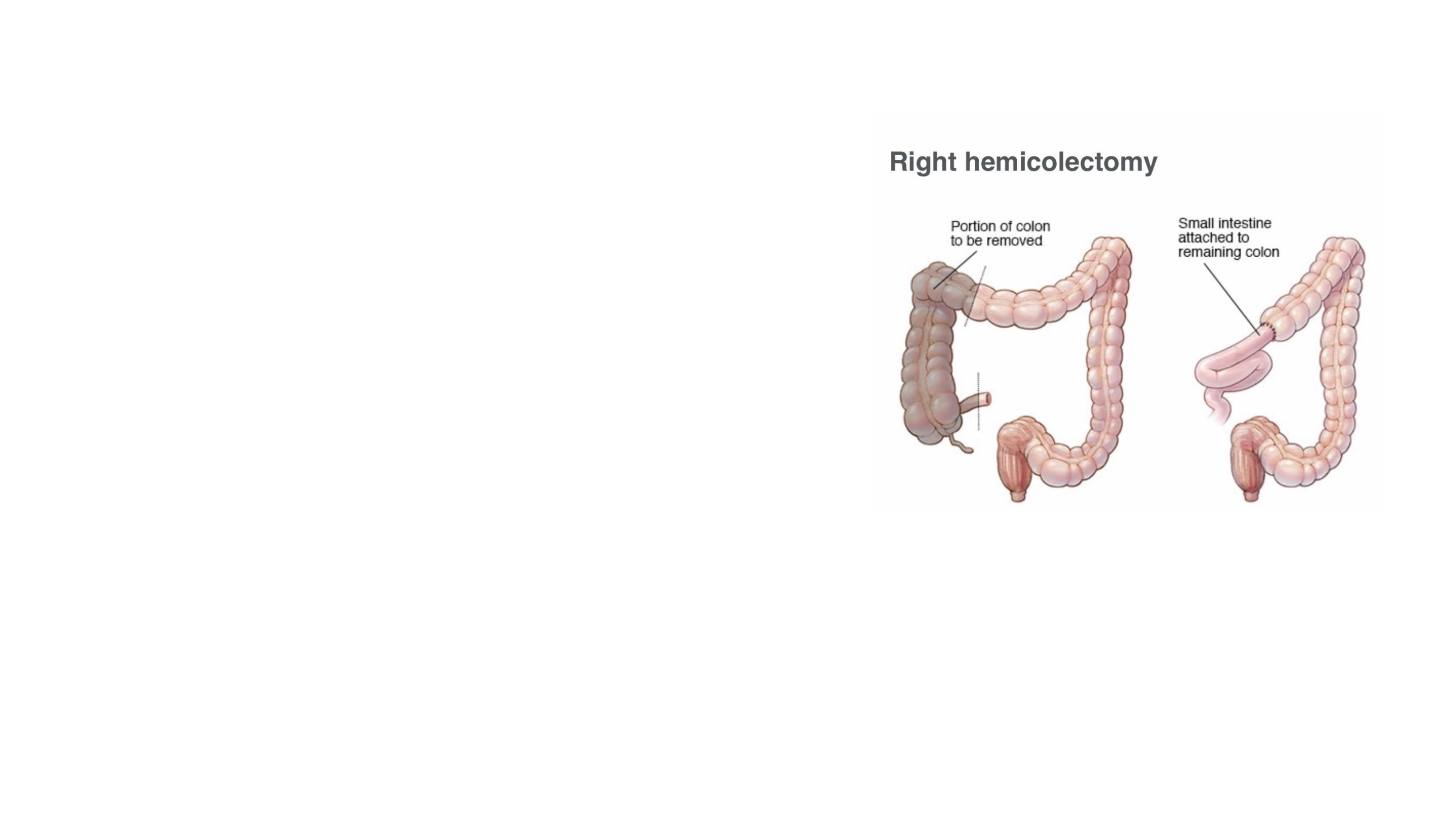

When a removable lesion is found in the caecum,

ascending colon, hepatic flexure or proximal

transverse colon, an emergency right

hemicolectomy should be performed.

A primary anastomosis is safe if the patient’s

general condition is reasonable.

If the lesion is irremovable (this is rarely the case), a

proximal stoma (colostomy or ileosotomy if the

ileocaecal valve is incompetent) or ileotransverse

bypass should be considered.

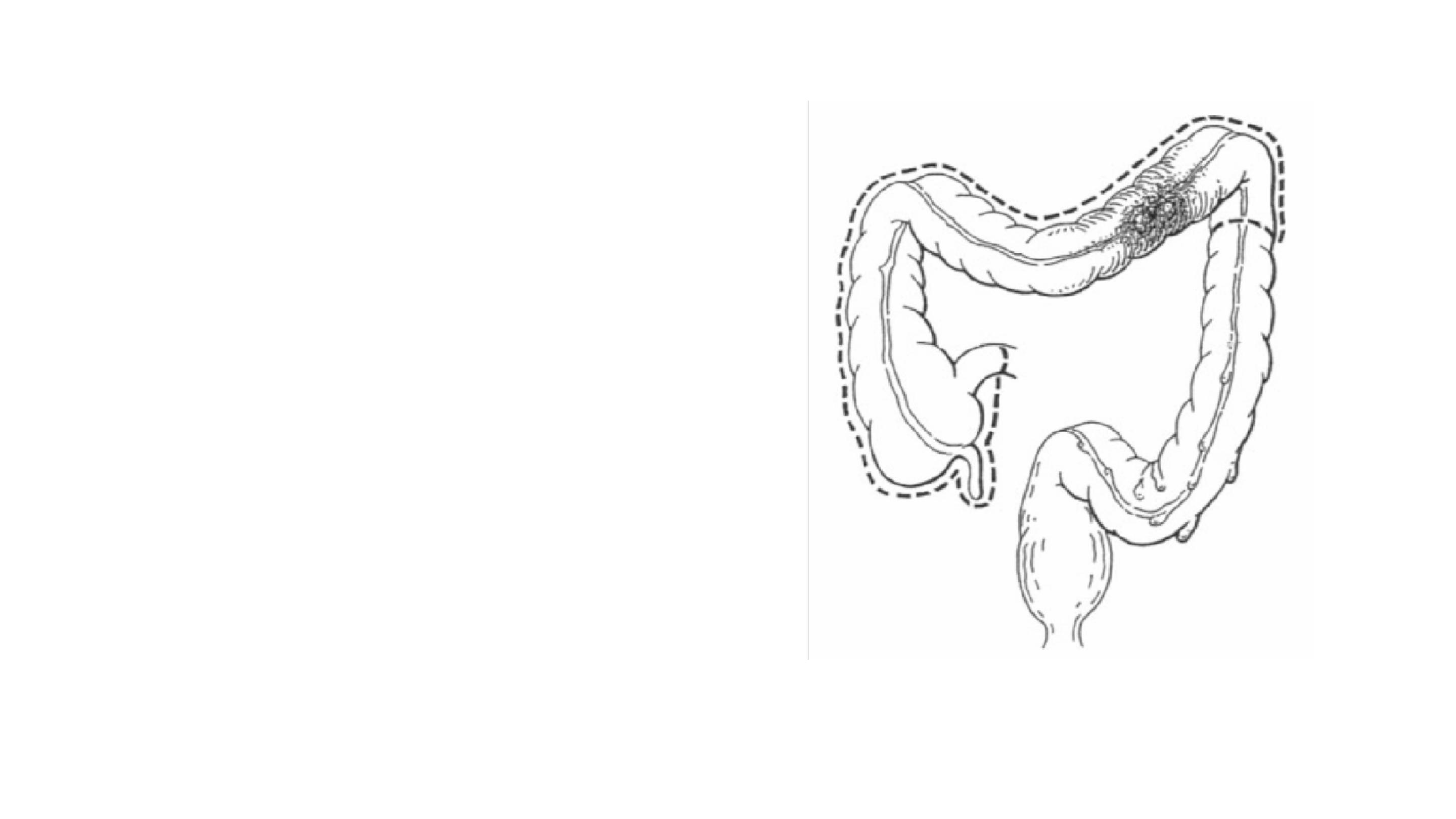

Obstructing lesions at the splenic flexure

should be treated by an extended right

hemicolectomy with ileo- descending

colonic anastomosis.

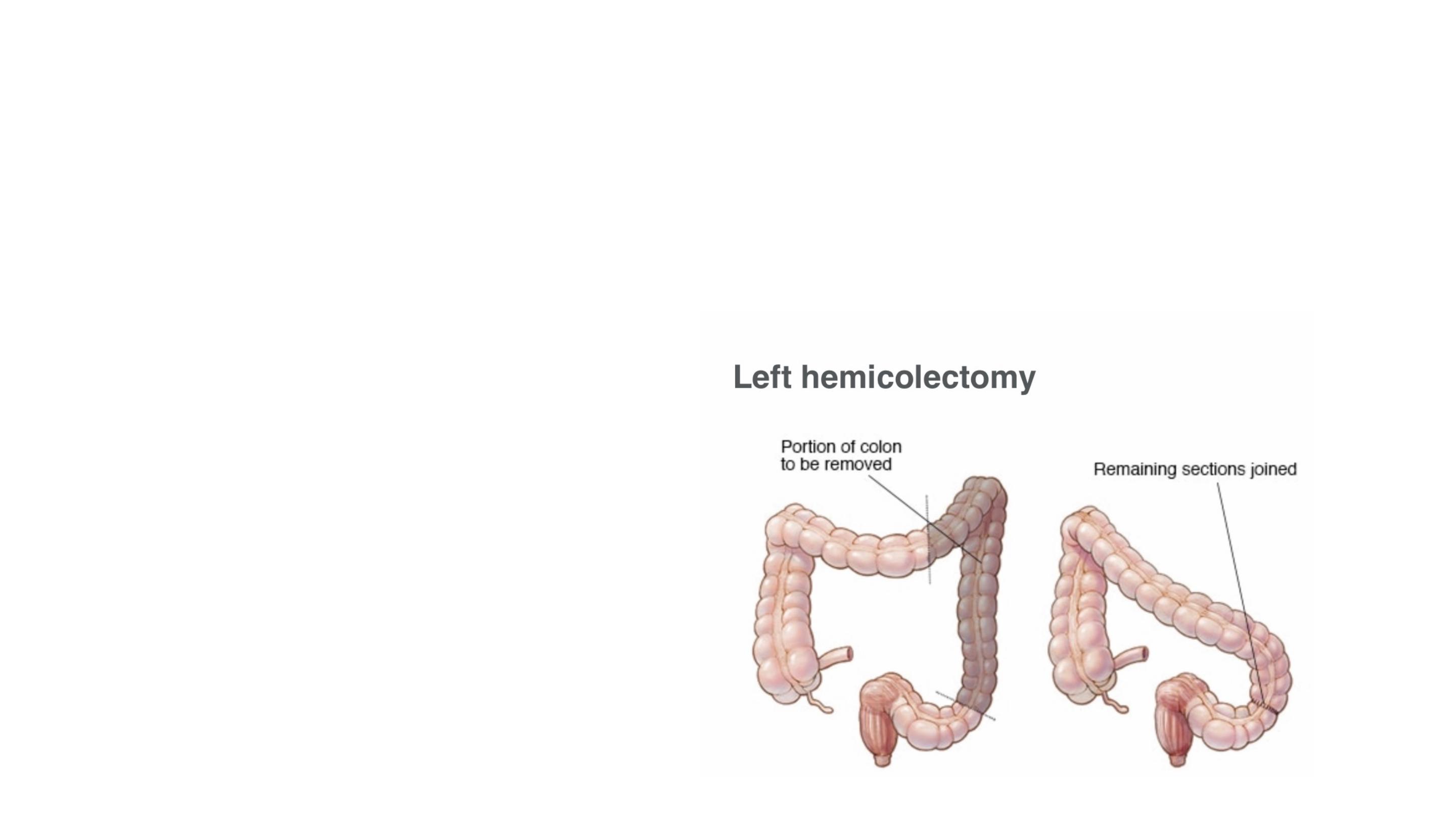

For obstructing lesions of the left colon or rectosigmoid junction,

immediate resection should be considered unless there are clear

contraindications

■ Inexperienced surgeon

■ Moribund patient

■ Advanced disease

Contraindications to immediate resection include:

In the absence of senior clinical staff, it is safest to bring the proximal

colon to the surface as a colostomy.

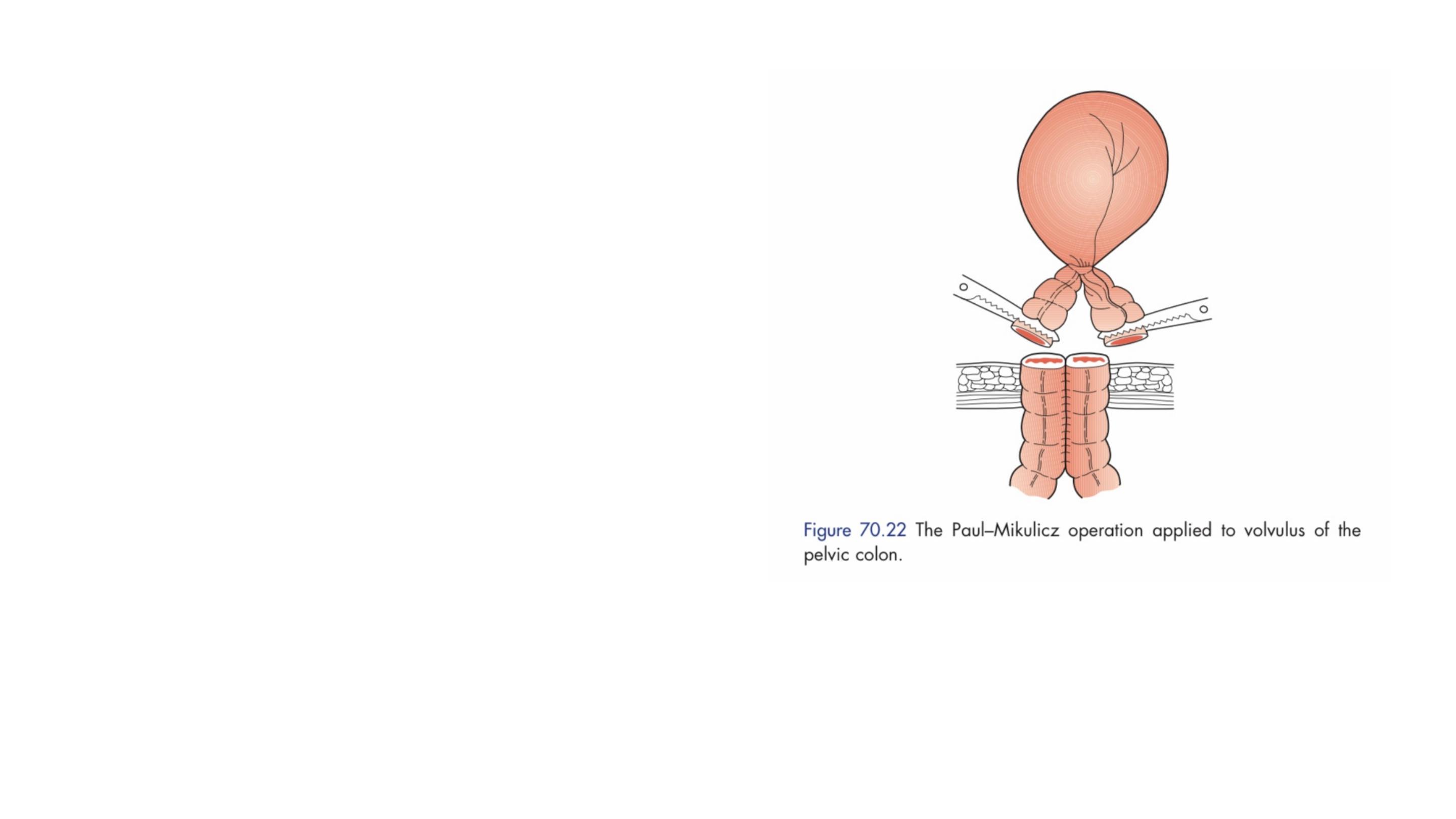

When possible, the distal bowel should be brought out at the same time

(Paul–Mikulicz procedure) to facilitate subsequent closure.

In the majority of cases, the distal

bowel will not reach and is closed and

returned to the abdomen (Hartmann’s

procedure).

A second-stage colorectal

anastomosis can be planned when the

patient is fit.

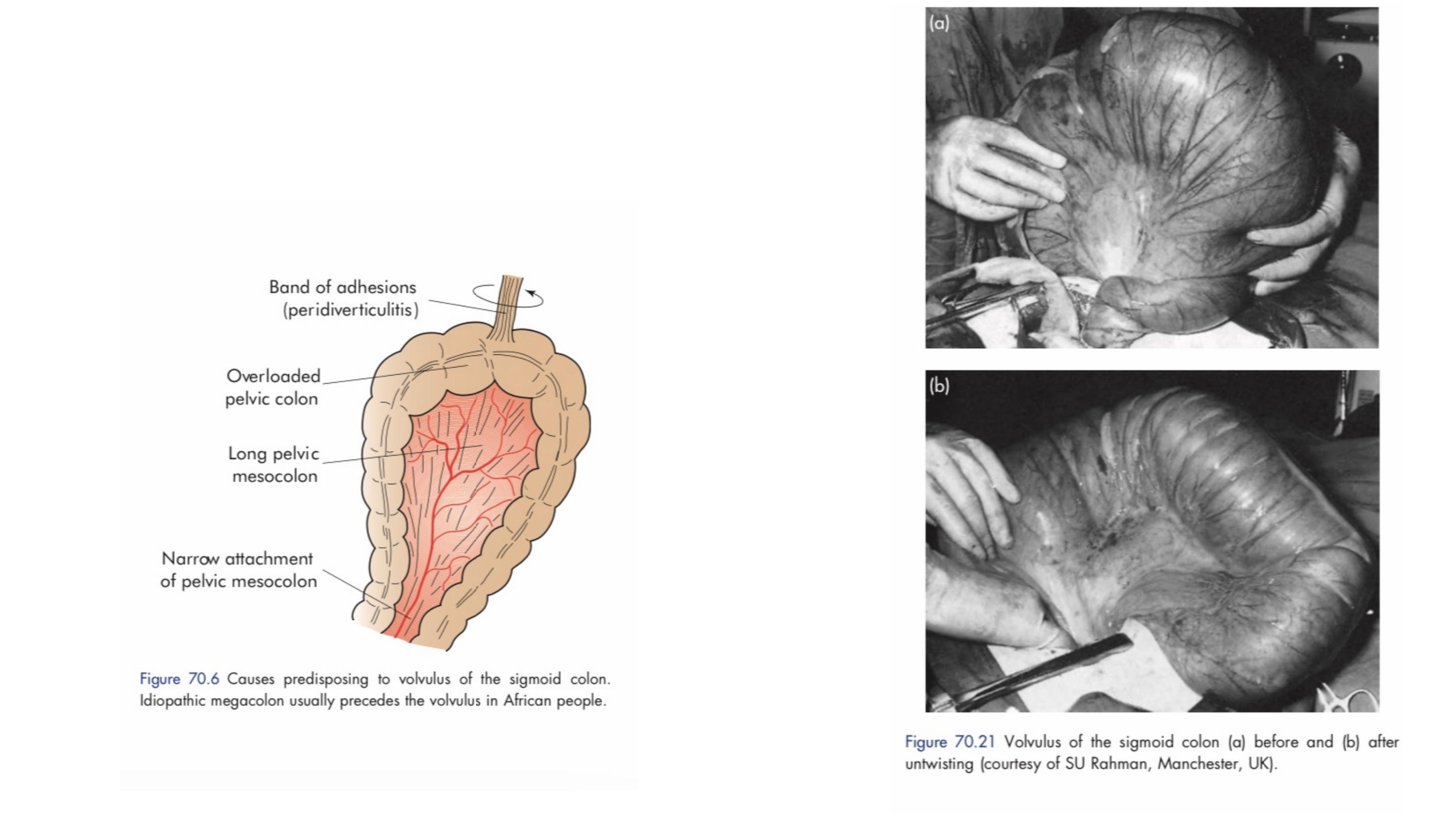

Sigmoid volvulus

The symptoms are of large bowel obstruction.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy or rigid sigmoidoscopy and insertion of a flatus tube

should be carried out to allow deflation of the gut.

The tube should be secured in place with tape for 24 hours and a repeat x-ray

taken to ensure that decompression has occurred.

Successful deflation, as long as ischaemic bowel is excluded, will resolve the

acute problem.

Treatment of sigmoid volvulus

In young patients, an elective sigmoid colectomy is required.

In the elderly patients , it is reasonable not to offer any further treatment following

successful endoscopic decompression as there is a high death rate (~80 per cent at

two years) from causes other than recurrent volvulus.

Failure results in an early laparotomy, with untwisting of the loop .

When the bowel is viable, fixation of the sigmoid colon to the posterior abdominal wall

may be a safer manoeuvre in inexperienced hands.

Resection is preferable if it can be achieved safely.

A Paul–Mikulicz procedure is

useful, particularly if there is

suspicion of impending gangrene.

an alternative procedure is a

sigmoid colectomy and, when

anastomosis is considered unwise,

a Hartmann’s procedure with

subsequent reanastomosis can be

carried out.

organic:

• intraluminal (rare) – faecal impaction;

• intrinsic intramural – strictures (Crohn’s disease,

ischaemia, diverticular), anastomotic stenosis;

• extrinsic intramural (rare) – metastatic deposits

(ovarian), endometriosis, stomal stenosis;

or functional:

• Hirschsprung’s disease, idiopathic megacolon, pseudo-

obstruction.

The causes of obstruction may be

CHRONIC LARGE BOWEL OBSTRUCTION

The symptoms of chronic obstruction differ in their predominance,

timing and degree from acute obstruction.

In functional cases, the symptoms may have been present for

months or years.

Plain abdominal radiography confirms the presence of large bowel

distension.

All such cases should be investigated by a subsequent single-contrast

water-soluble enema study, CT scan or endoscopic assessment to rule

out functional disease

Organic disease requires decompression with either

a laparotomy or stent.

Stomal stenosis can usually be managed at the

abdominal wall level.

Surgical management after resuscitation depends

on the underlying cause.

Functional disease requires colonoscopic

decompression in the first instance and

conservative management.

Intestinal perforation can occur in patients

with functional obstruction.

Paralytic ileus

This may be defined as a state in which there is failure of transmission of

peristaltic waves secondary to neuromuscular failure (i.e. in the myenteric

(Auerbach’s) and submucous (Meissner’s) plexuses).

The resultant stasis leads to accumulation of fluid and gas within the bowel,

with associated distension, vomiting, absence of bowel sounds and

absolute constipation.

ADYNAMIC OBSTRUCTION

The following varieties are recognised:

• Postoperative. A degree of ileus usually occurs after any abdominal

procedure and is self-limiting, with a variable duration of 24–72 hours.

Postoperative ileus may be prolonged in the presence of hypoproteinaemia

or metabolic abnormality.

• Infection. Intra-abdominal sepsis may give rise to localised or generalised

ileus.

• Reflex ileus. This may occur following fractures of the spine or ribs,

retroperitoneal haemorrhage or even the application of a plaster jacket.

• Metabolic. Uraemia and hypokalaemia are the most common contributory

factors.

Paralytic ileus takes on a clinical significance if, 72 hours after

laparotomy:

• there has been no return of bowel sounds on auscultation;

• there has been no passage of flatus.

Abdominal distension becomes more marked and tympanitic.

Colicky pain is not a feature.

Distension increases pain from the abdominal wound.

Effortless vomiting may occur.

Radiologically, the abdomen shows gas- filled loops of intestine with multiple

fluid levels (if an erect film is felt necessary).

Clinical features

Paralytic ileus is managed with the use of nasogastric suction and restriction of oral

intake until bowel sounds and the passage of flatus return.

Electrolyte balance must be maintained.

The use of an enhanced recovery programme with early introduction of fluids and

solids is, however, becoming increasingly popular.

In resistant cases, medical therapy with a gastroprokinetic agent, such as

domperidone or erythromycin may be used, provided that an intraperitoneal cause

has been excluded.

Management

If paralytic ileus is prolonged, CT scanning is the most effective

investigation; it will demonstrate any intra-abdominal sepsis or

mechanical obstruction and therefore guide any requirement for

laparotomy.

The need for a laparotomy becomes increasingly likely the longer the

bowel inactivity persists, particularly if it lasts for more than 7 days or if

bowel activity recommences following surgery and then stops again.

This condition describes an obstruction,

usually of the colon, that occurs in the

absence of a mechanical cause or acute intra-

abdominal disease.

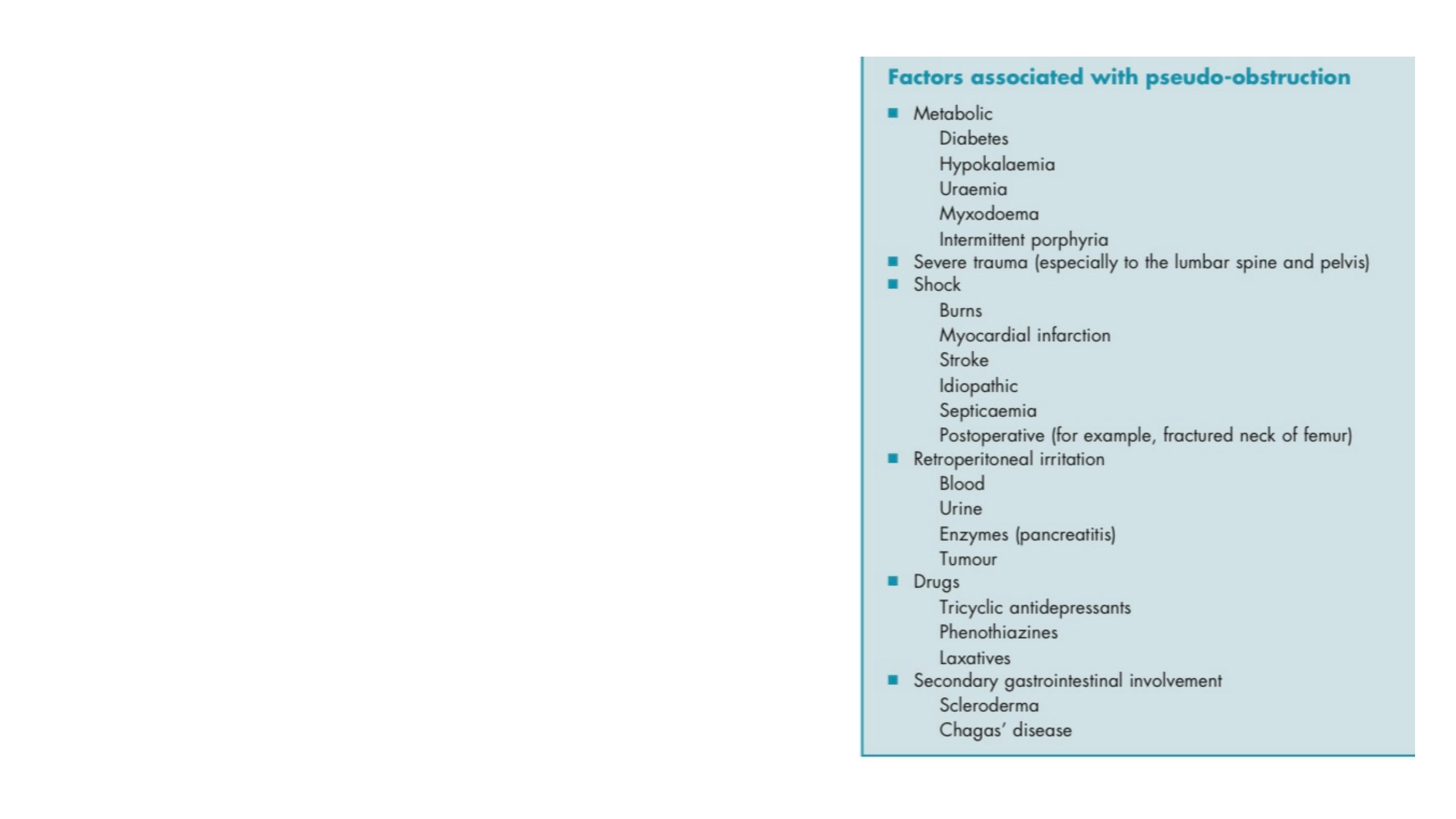

It is associated with a variety of syndromes in

which there is an underlying neuropathy and/

or myopathy and a range of other factors

Pseudo-obstruction

Presents as acute large bowel obstruction.

The absence of a mechanical cause requires urgent confirmation by colonoscopy or

a single-contrast water-soluble barium enema or CT.

Once confirmed, pseudo-obstruction requires treatment of any identifiable cause.

If this is ineffective, intravenous neostigmine should be given.

If neostigmine is not effective, colonoscopic decompression should be performed.

Abdominal examination should pay attention to tenderness and peritonism over the

caecum and as with mechanical obstruction, caecal perforation is more likely if the

caecal diameter is 14 cm or greater.

Surgery is associated with high morbidity and mortality and should be reserved for

those with impending perforation when other treatments have failed or perforation

has occurred.

Ogilvie’s syndrome