Gall Bladder

Assist. Prof . Dr Salah aljanaby

General surgeon and laparoscopic surgeon

Babylon medical college

Lecture 1

Anatomy

■

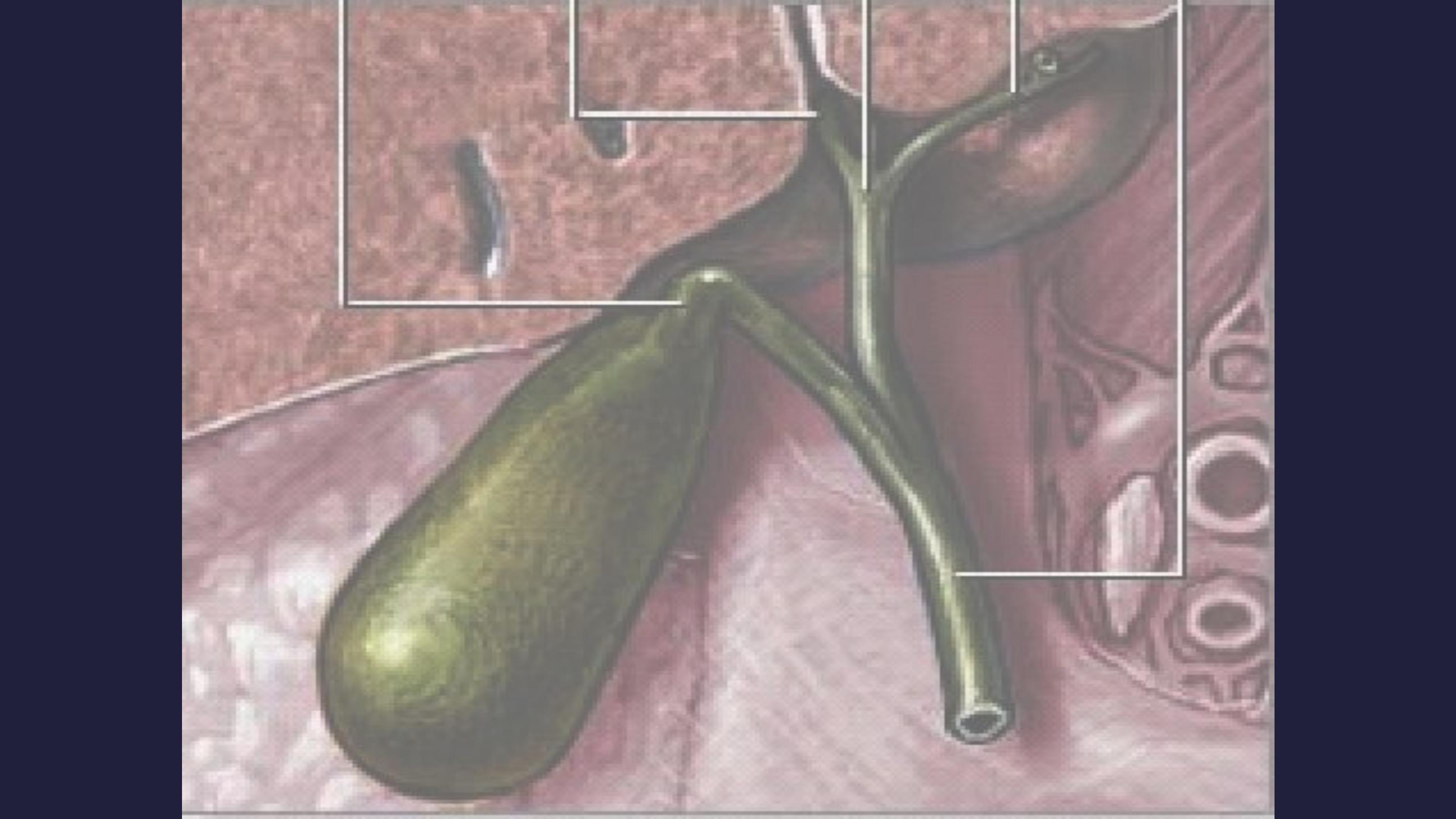

The gallbladder (or

cholecyst,

sometimes gall

bladder) is a pear-

shaped organ that

stores about 50 mL

of bile (or "gall") until

the body needs it for

digestion.

Anatomy

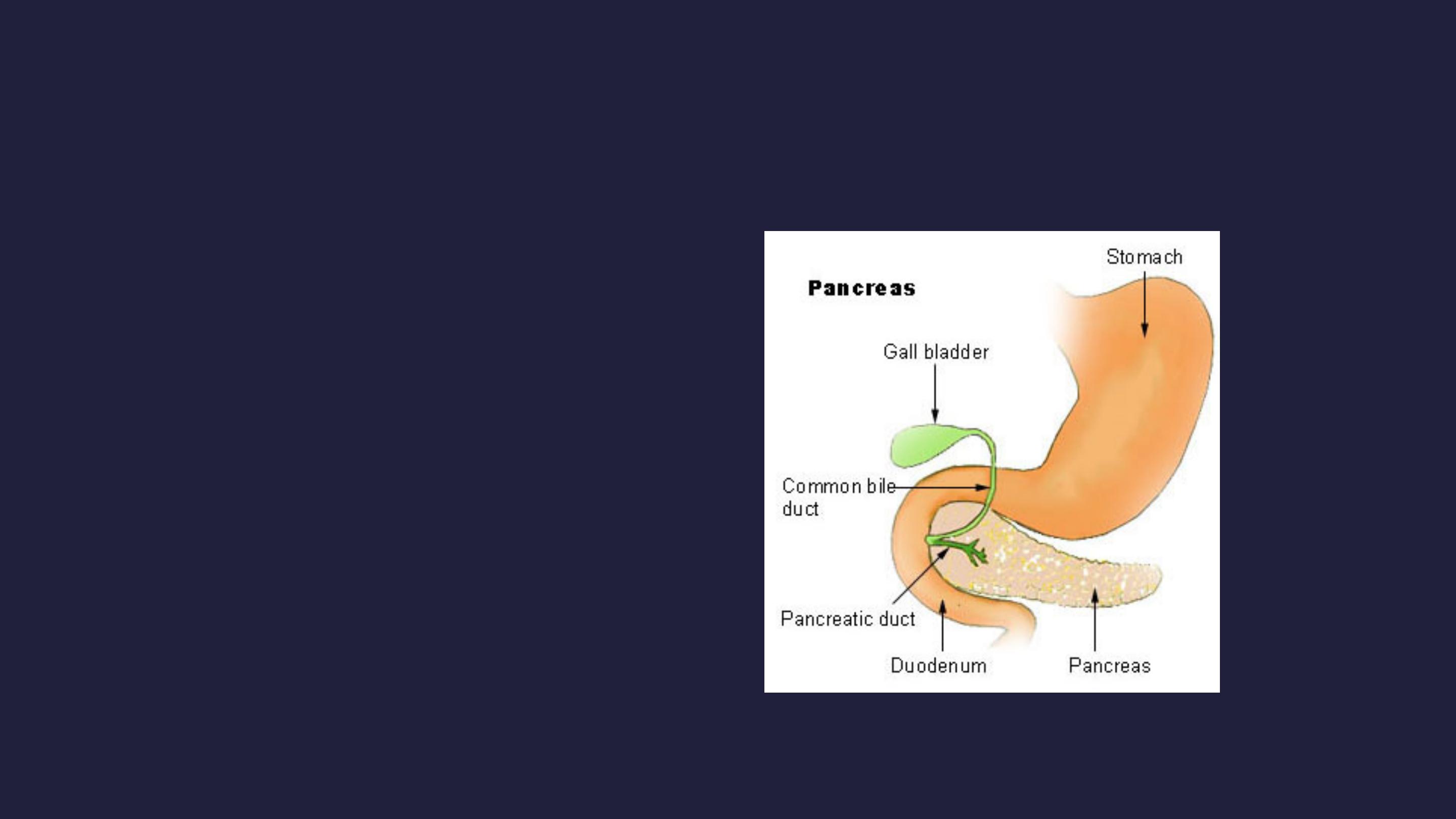

The gallbladder is about 7-10 cm

long in humans and appears

dark green because of its

contents (bile), rather than its

tissue. It is connected to the liver

and the duodenum by the biliary

tract.

■

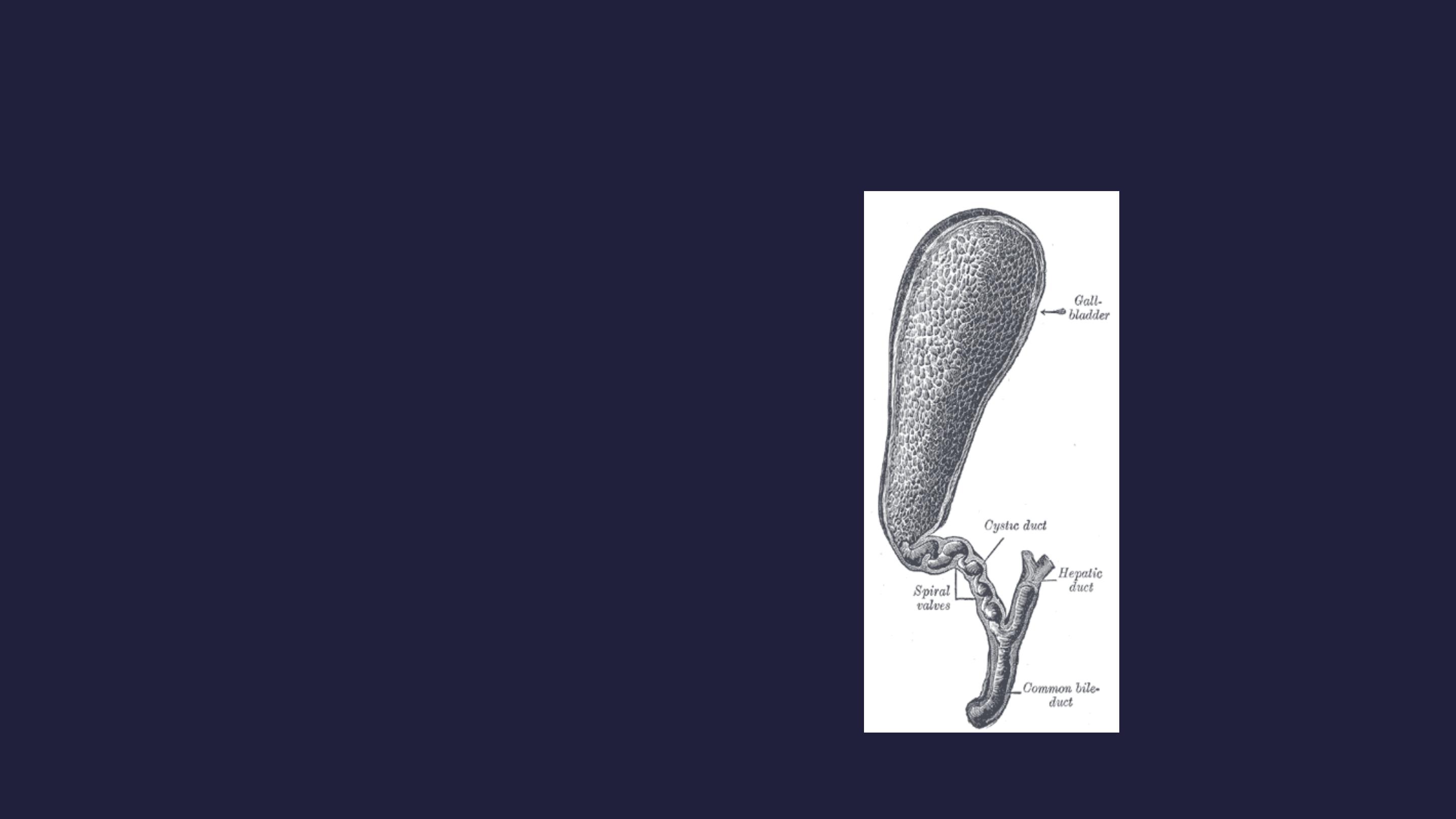

The cystic duct leads from the

gallbladder and joins with the

common hepatic duct to form the

common bile duct.

■

The common bile duct then joins

with the pancreatic duct, and

enters the duodenum through

the hepatopancreatic ampulla at

the major duodenal papilla.

Anatomy

Artery

Cystic artery

Vein

Cystic vein

Nerve

Celiac ganglia, vagus

Precursor

Foregut

Histology

The layers of the gallbladder are as follows:

■

The gallbladder has a simple columnar epithelial lining

characterized by recesses called Aschoff's recesses

(lacunae of Luschka) , which are pouches inside the

lining.

■

Under the epithelium there is a layer of connective

tissue.

■

Beneath the connective tissue is a wall of smooth

muscle that contracts in response to cholecystokinin,

a peptide hormone secreted by the duodenum.

■

There is essentially no submucosa.

Function

■

The gallbladder stores about 50 mL of bile , which is

released when food containing fat enters the digestive

tract, stimulating the secretion of cholecystokinin

(CCK). The bile, produced in the liver, emulsifies fats

and neutralizes acids in partly digested food.

■

After being stored in the gallbladder, the bile becomes

more concentrated than when it left the liver,

increasing its potency and intensifying its effect on

fats. Most digestion occurs in the duodenum.

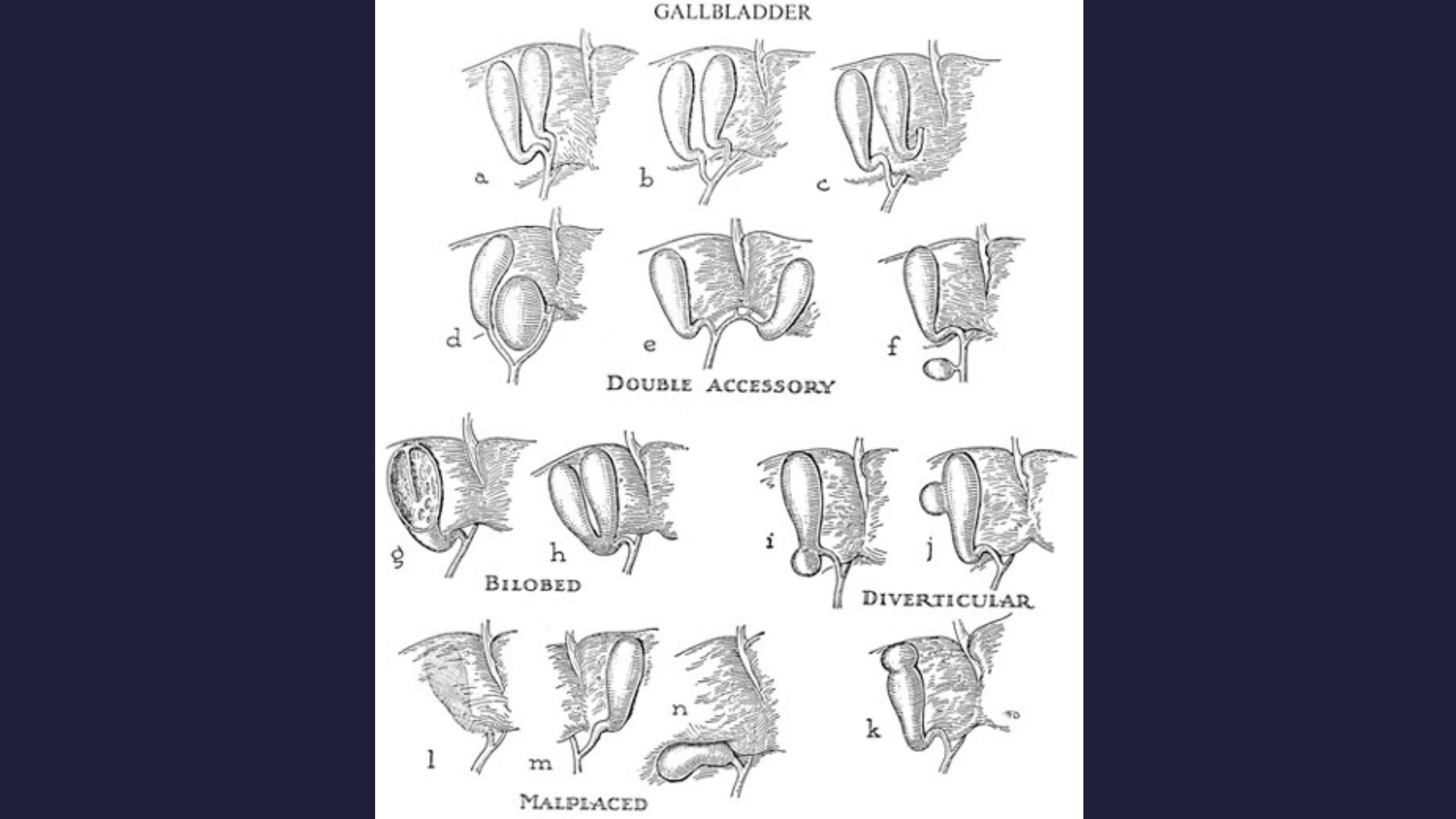

Anomalies

■

The gallbladder may be absent = 0.075%

■

The gallbladder and cystic duct may be absence.

■

the gallbladder is irregular in form or constricted

across its middle; more rarely, it is partially divided in

a longitudinal direction.

■

two distinct gallbladders, each having a cystic duct

that joined the hepatic duct. (0.026%), The cystic duct

may itself be doubled

■

The gallbladder has been found on the left side (to the

left of the ligamentum teres) in subjects in whom there

was no general tranposition of the thoracic and

abdominal viscera.

■

The gallbladder may be intrahepatic or

beneath the left lobe. Ectopic sites include

retrohepatic positions, or in the anterior

abdominal wall or falciform ligament, they may

be suprahepatic or transversely position,

floating, or retroperitoneal. They may be in the

midline anterior epigastric above the left lobe

or suprahepatic above the right hepatic lobe.

Choledochal cyst

■

Choledochal cysts are congenital anomalies of the

bile ducts. They consist of cystic dilatations of the

extrahepatic biliary tree, intrahepatic biliary radicles,

or both.

■

Douglas is credited with the first clinical report in a 17-

year-old girl who presented with intermittent

abdominal pain, jaundice, fever, and a palpable

abdominal mass.

■

Pathophysiology: The pathogenesis of choledochal

cysts is most likely multifactorial.

■

A congenital etiology,

■

A congenital predisposition to acquiring the disease under

the right conditions.

■

The vast majority of patients with choledochal

cysts have an anomalous junction of the

common bile duct with the pancreatic duct

(anomalous pancreatobiliary junction [

APBJ

]).

An APBJ is characterized when the pancreatic

duct enters the common bile duct 1 cm or

more proximal to where the common bile duct

reaches the ampulla of Vater.

■

APBJs in more than 90% of patients with

choledochal cysts.

■

The APBJ allows pancreatic secretions and

enzymes to reflux into the common bile duct.

In the relatively alkaline conditions found in

the common bile duct, pancreatic pro-

enzymes can become activated. This results

in inflammation and weakening of the bile duct

wall. Severe damage may result in complete

denuding of the common bile duct mucosa.

■

From a congenital standpoint, defects in

epithelialization and recanalization of the

developing bile ducts during organogenesis

and congenital weakness of the duct wall have

also been implicated. The result is formation

of a choledochal cyst.

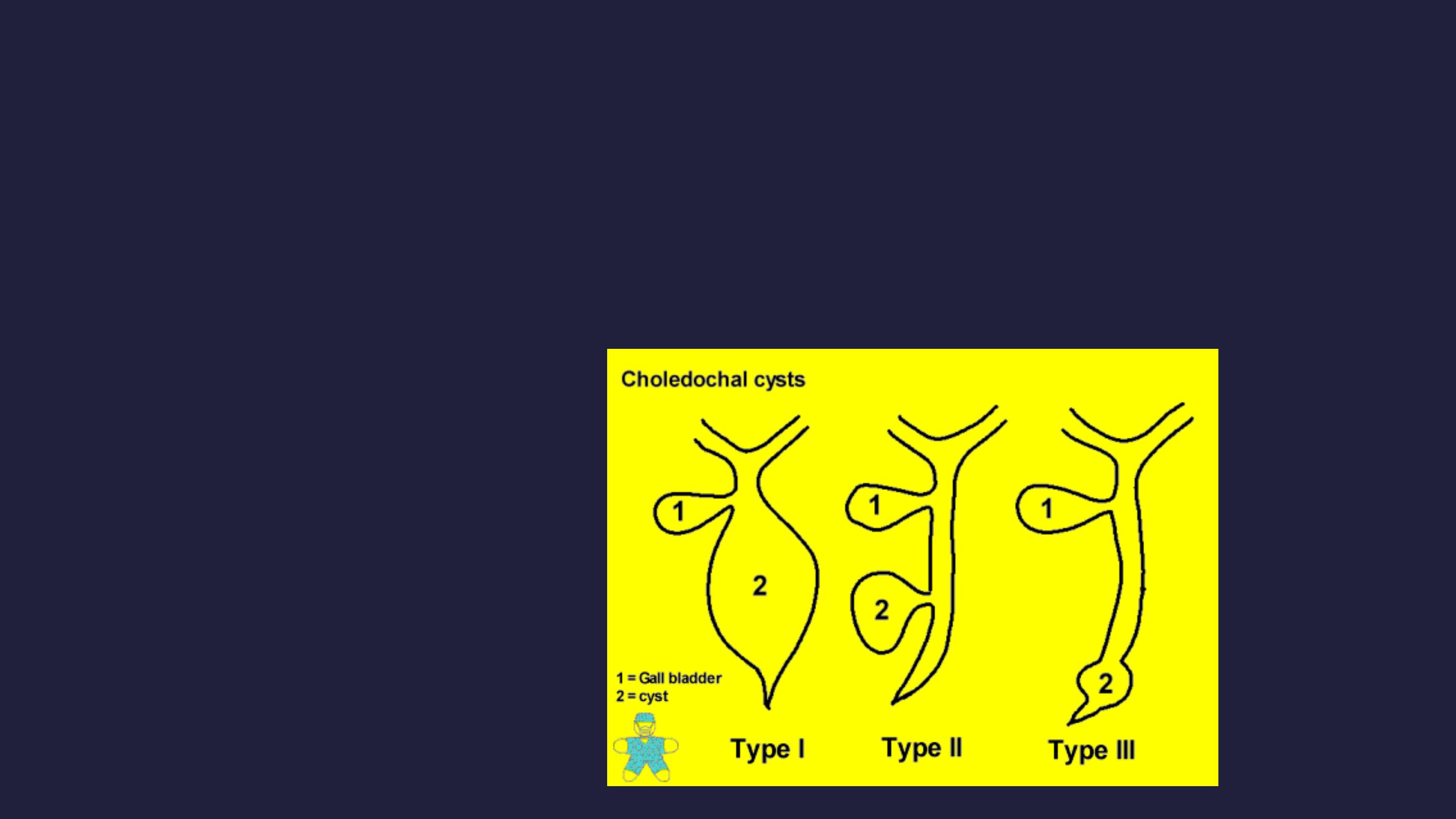

Anatomy of Choledochal cyst

based on the Todani classification published in 1977.

■

Type I choledochal cysts

■

most common ; 80-90% of the lesions.

■

Type I cysts are dilatations of the entire common hepatic

and common bile ducts or segments of each.

■

They can be saccular or fusiform in configuration.

■

Type II choledochal cysts

■

isolated protrusions or diverticula that project from the

common bile duct wall. They may be sessile or may be

connected to the common bile duct by a narrow stalk.

■

Type III choledochal cysts are found in the

intraduodenal portion of the common bile duct.

Another term used for these cysts is choledochocele.

■

Type IVA cysts are characterized by multiple dilatations of the

intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tree. Most frequently, a large

solitary cyst of the extrahepatic duct is accompanied by multiple

cysts of the intrahepatic ducts. Type IVB choledochal cysts

consist of multiple dilatations that involve only the extrahepatic

bile duct.

■

Type V choledochal cysts are defined by dilatation of the

intrahepatic biliary radicles. Often, numerous cysts are present

with interposed strictures that predispose the patient to

intrahepatic stone formation, obstruction, and cholangitis. The

cysts are typically found in both hepatic lobes. Occasionally,

unilobar disease is found and most frequently involves the left

lobe.

■

The patient may present at any age with

1.

Obstructive jaundice

2.

Cholangitis and

3.

Abd signs, with RUQ swelling in some cases

■

It is a premalignant condition

■

Diagnosis by US and MRI

■

Radical excision of the cyst is the treatment

of choice with Roux – en –Y reconstruction

Gall stones

■

Gall stones are the most common abdominal reason

for admission to hospital in developed countries and

account for an important part of healthcare

expenditure. Around 5.5 million people have gall

stones in the United Kingdom, and over 50 000

cholecystectomies are performed each year.

■

Normal bile consists of 70% bile salts (mainly cholic

and chenodeoxycholic acids), 22% phospholipids

(lecithin), 4% cholesterol, 3% proteins, and 0.3%

bilirubin.

■

There are two major types of gallstones, which seem

to form due to distinctly different pathogenetic

mechanisms.

Cholesterol Stones

■

About 90% of gallstones are of this type.

These stones can be either;

■

almost pure cholesterol {Cholesterol stones}

■

or mixtures of cholesterol and other

substances{ cholesterol predominant (mixed)

stones}.

■

The key event leading to formation and

progression of cholesterol stones is

precipitation of cholesterol in bile.

■

Unesterified cholesterol is virtually insoluble

in aqueous solutions and is kept in solution

in bile largely by virtue of the detergent-like

effect of bile salts.

Imbalance lead to stone formation

■

Hyper-secretion of cholesterol into bile due to

■

obesity,

■

acute high calorie intake,

■

chronic polyunsaturated fat diet, contraceptive

steroids or pregnancy,

■

diabetes mellitus and

■

certain forms of familial hypercholesterolemia.

■

Hypo-secretion of bile salts due to

■

impaired bile salt synthesis and

■

abnormal intestinal loss of bile salts (e.g. recirculation

failure due to ileal disease).

■

Impaired gallbladder function with incomplete

emptying or stasis.

■

seen in late pregnancy

■

with oral contraceptive use,

■

in patients on total parenteral nutrition and

■

due to unknown causes, perhaps associated with neuro-

endocrine dysfunction.