1

بسم هللا الرحمن الرحيم

Lecture -3- Medical Physiology (GIT system)

2

nd

stage Dr. Noor Jawad

Ingestion of food

Objectives of our lecture:

1. What is the mechanisms of food ingestion?

2. Stages of swallowing?

The amount of food that a person ingests is determined principally

by an intrinsic desire for food called hunger. The type of food that a

person preferentially seeks is determined by appetite. These

mechanisms are extremely important for maintaining an adequate

nutritional supply for the body and in relation to nutrition of the

body.

Mechanisms of food ingestion:

1. Mastication ( chewing)

The teeth are admirably designed for chewing. The anterior teeth

(incisors) provide a strong cutting action, and the posterior teeth

(molars) provide a grinding action. All the jaw muscles working

together can close the teeth with a force as great as 55 pounds on the

incisors and 200 pounds on the molars.

2

Most of the muscles of chewing are innervated by the motor branch

of the fifth cranial nerve, and the chewing process is controlled by

nuclei in the brain stem. Stimulation of specific reticular areas in the

brain stem taste centers will cause rhythmical chewing movements.

In addition, stimulation of areas in the hypothalamus, amygdala, and

even the cerebral cortex near the sensory areas for taste and smell

can cause chewing.

Much of the chewing process is caused by a chewing reflex. The

presence of a bolus of food in the mouth at first initiates reflex

inhibition of the muscles of mastication, which allows the lower jaw

to drop. This action automatically raises the jaw to cause closure of

the teeth, but it also compresses the bolus again against the linings

of the mouth, which inhibits the jaw muscles once again, allowing

3

the jaw to drop and rebound another time; this process is repeated

again and again.

Chewing is important for digestion of all foods, but it is especially

important for most fruits and raw vegetables because they have

indigestible cellulose membranes around their nutrient portions that

must be broken before the food can be digested. Furthermore,

chewing aids the digestion of food for another simple reason:

Digestive enzymes act only on the surfaces of food particles;

therefore, the rate of digestion is dependent on the total surface area

exposed to the digestive secretions.

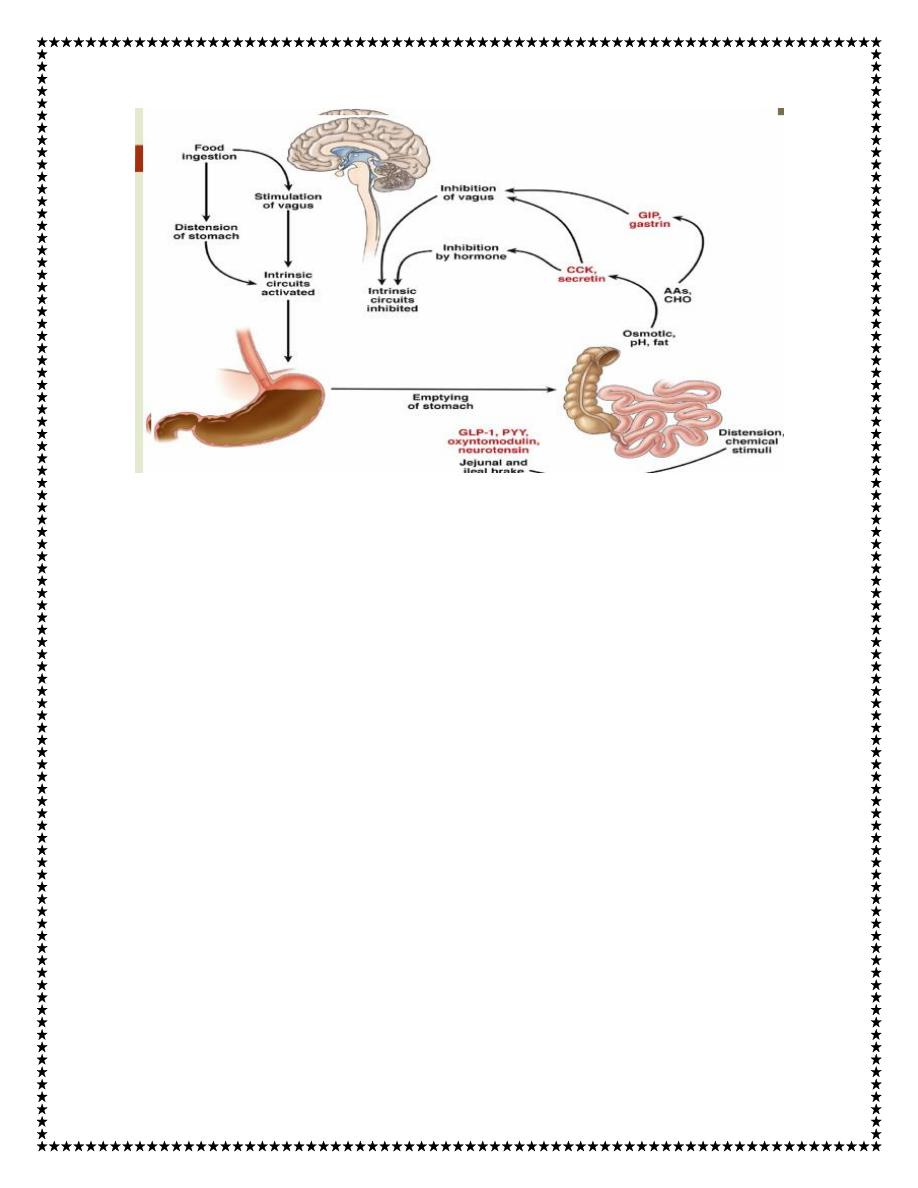

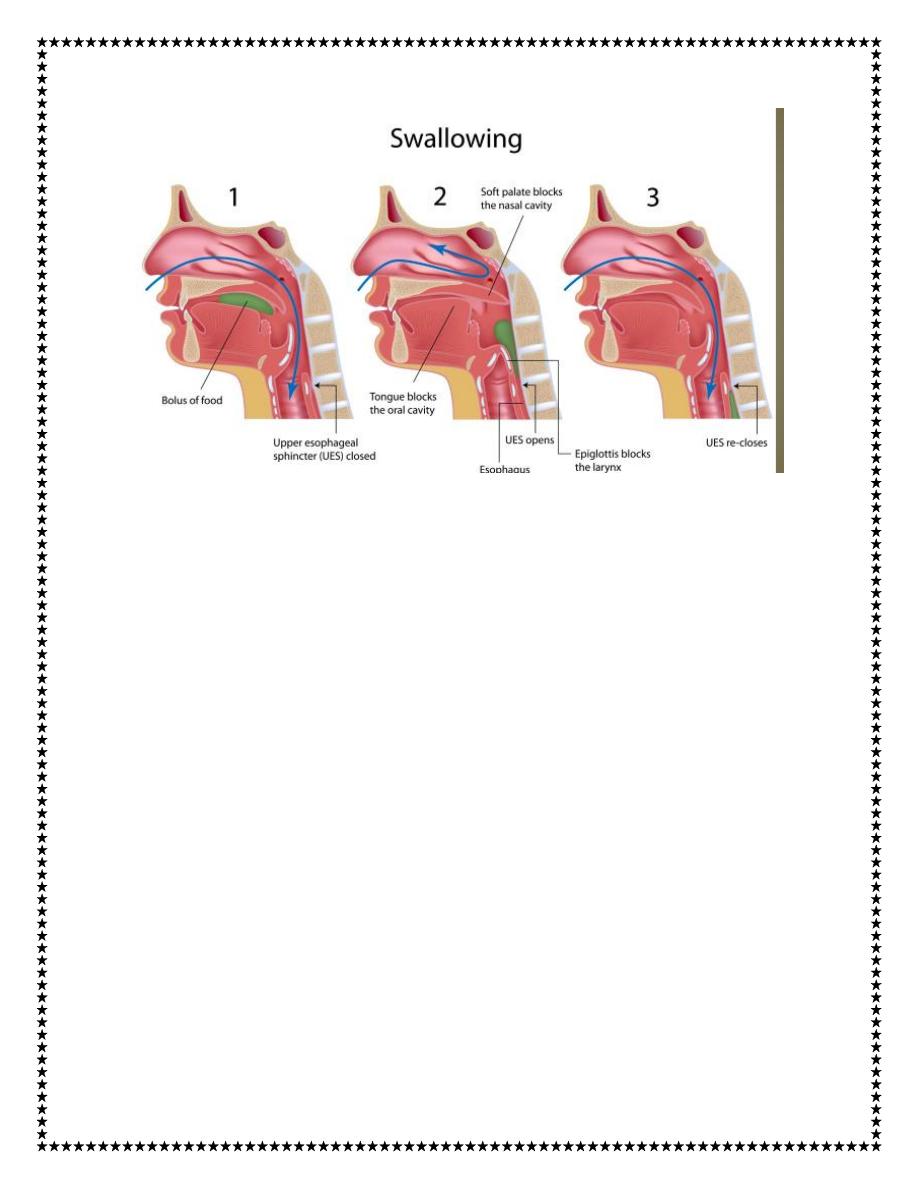

2. Swallowing (Deglutition)

Swallowing is a complicated mechanism, principally because the

pharynx subserves respiration and swallowing. The pharynx is

converted for only a few seconds at a time into a tract for propulsion

of food. It is especially important that respiration not be

compromised because of swallowing.

In general, swallowing can be divided into (1) a voluntary stage,

which initiates the swallowing process; (2) a pharyngeal stage,

which is involuntary and constitutes passage of food through the

pharynx into the esophagus; and (3) an esophageal stage, another

involuntary phase that transports food from the pharynx to the

stomach.

4

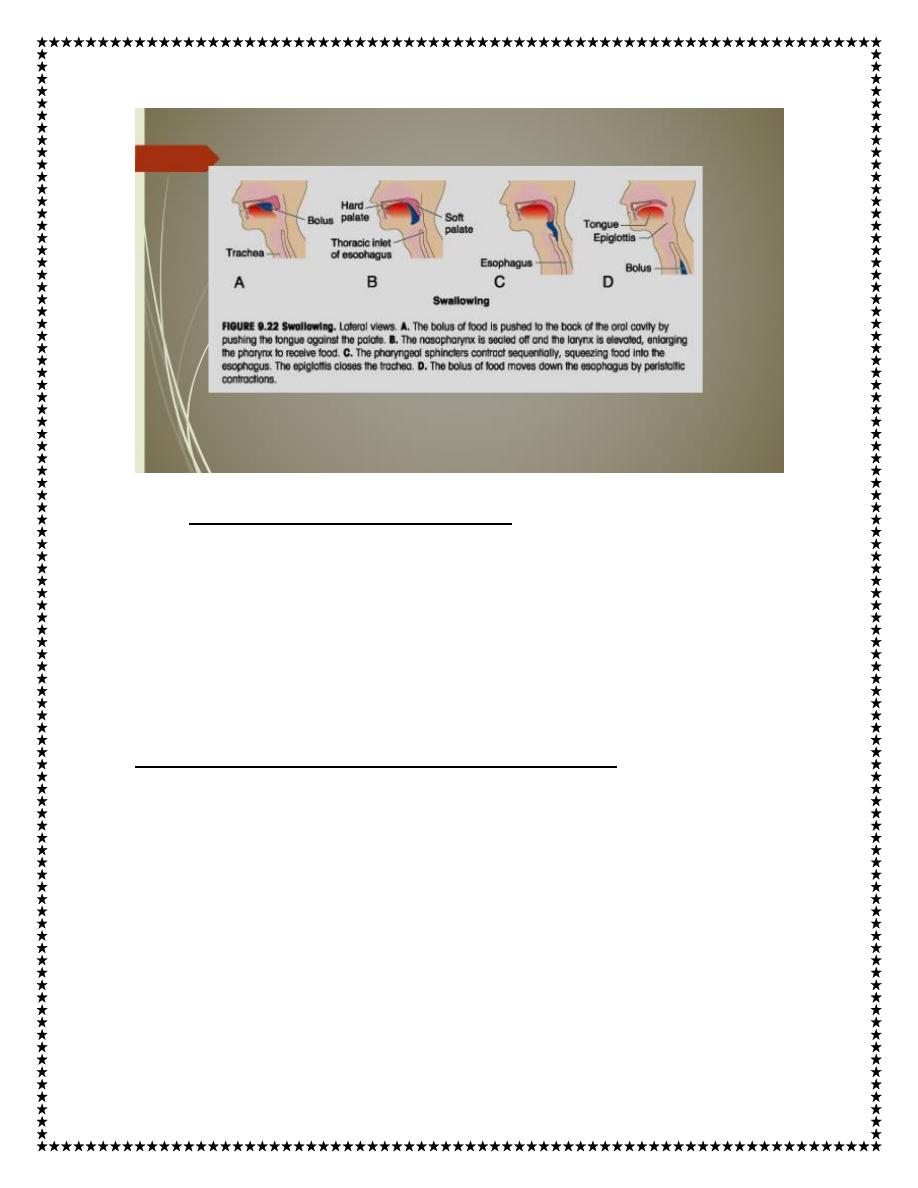

1. Voluntary Stage of Swallowing.

When the food is ready for swallowing, it is “voluntarily” squeezed

or rolled posteriorly into the pharynx by pressure of the tongue

upward and backward against the palate, as shown in Figure .

2. Involuntary Pharyngeal Stage of Swallowing

As the bolus of food enters the posterior mouth and pharynx, it

stimulates epithelial swallowing receptor areas all around the

opening of the pharynx, especially on the tonsillar pillars, and

impulses from these areas pass to the brain stem to initiate a series

of automatic pharyngeal muscle contractions as follows:

5

1. The soft palate is pulled upward to close the posterior nares to

prevent reflux of food into the nasal cavities.

2. The palatopharyngeal folds on each side of the pharynx are pulled

medially to approximate each other. In this way, these folds form a

sagittal slit through which the food must pass into the posterior

pharynx. This slit performs a selective action, allowing food that has

been masticated sufficiently to pass with ease. Because this stage of

swallowing lasts less than 1 second, any large object is usually

impeded too much to pass into the esophagus.

3. The vocal cords of the larynx are strongly approximated, and the

larynx is pulled upward and anteriorly by the neck muscles. These

actions, combined with the presence of ligaments that prevent

upward movement of the epiglottis, cause the epiglottis to swing

6

backward over the opening of the larynx. All these effects acting

together prevent passage of food into the nose and trachea.

4. The upward movement of the larynx also lifts the glottis out of

the main stream of food flow, so the food mainly passes on each side

of the epiglottis rather than over its surface; this action adds still

another protection against entry of food into the trachea.

5. Once the larynx is raised and the pharyngoesophageal sphincter

becomes relaxed, the entire muscular wall of the pharynx contracts,

beginning in the superior part of the pharynx, then spreading

downward over the middle and inferior pharyngeal areas, which

propels the food by peristalsis into the esophagus.

To summarize the mechanics of the pharyngeal stage of swallowing:

The trachea is closed, the esophagus is opened, and a fast peristaltic

wave initiated by the nervous system of the pharynx forces the bolus

of food into the upper esophagus, with the entire process occurring

in less than 2 seconds.

3. The Esophageal Stage of Swallowing Involves Two Types

of Peristalsis.

The esophagus functions primarily to conduct food rapidly from the

pharynx to the stomach, and its movements are organized

specifically for this function. The esophagus normally exhibits two

7

types of peristaltic movements: primary peristalsis and secondary

peristalsis.

Primary peristalsis is simply continuation of the peristaltic wave

that begins in the pharynx and spreads into the esophagus during the

pharyngeal stage of swallowing. This wave passes all the way from

the pharynx to the stomach in about 8 to 10 seconds.

Food swallowed by a person who is in the upright position is usually

transmitted to the lower end of the esophagus even more rapidly than

the peristaltic wave itself, in about 5 to 8 seconds, because of the

additional effect of gravity pulling the food downward.

If the primary peristaltic wave fails to move all the food that has

entered the esophagus into the stomach, secondary peristaltic waves

result from distention of the esophagus itself by the retained food;

these waves continue until all the food has emptied into the stomach.

The secondary peristaltic waves are initiated partly by intrinsic

neural circuits in the myenteric nervous system and partly by

reflexes that begin in the pharynx and are then transmitted upward

through vagal afferent fibers to the medulla and back again to the

esophagus through glossopharyngeal and vagal efferent nerve

fibers.

The musculature of the pharyngeal wall and upper third of the

esophagus is striated muscle. Therefore, the peristaltic waves in

8

these regions are controlled by skeletal nerve impulses from the

glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. In the lower two thirds of the

esophagus, the musculature is smooth muscle, but this portion of the

esophagus is also strongly controlled by the vagus nerves that act

through connections with the esophageal myenteric nervous system.

When the vagus nerves to the esophagus are cut, the myenteric nerve

plexus of the esophagus becomes excitable enough after several

days to cause strong secondary peristaltic waves even without

support from the vagal reflexes. Therefore, even after paralysis of

the brain stem swallowing reflex, food fed by tube or in some other

way into the esophagus still passes readily into the stomach.

Function of the Lower Esophageal Sphincter (Gastroesophageal

Sphincter).

At the lower end of the esophagus, extending upward about 3

centimeters above its juncture with the stomach, the esophageal

circular muscle functions as a broad lower esophageal sphincter,

also called the gastroesophageal sphincter. This sphincter

normally remains tonically constricted with an intraluminal pressure

at this point in the esophagus of about 30 mm Hg, in contrast to the

midportion of the esophagus, which normally remains relaxed.

When a peristaltic swallowing wave passes down the esophagus,

“receptive relaxation” of the lower esophageal sphincter occurs

9

ahead of the peristaltic wave, which allows easy propulsion of the

swallowed food into the stomach. Rarely, the sphincter does not

relax satisfactorily, resulting in a condition called achalasia.

The stomach secretions are highly acidic and contain many

proteolytic enzymes, and esophageal mucosa, except in the lower

one eighth of the esophagus, is not capable of resisting the digestive

action of gastric secretions for long. Fortunately, the tonic

constriction of the lower esophageal sphincter helps prevent

significant reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus except

under abnormal conditions

Additional Prevention of Esophageal Reflux by Valvelike

Closure of the Distal End of the Esophagus.

Another factor that helps prevent reflux is a valvelike mechanism of

a short portion of the esophagus that extends slightly into the

stomach. Increased intraabdominal pressure caves the esophagus

inward at this point. Thus, this valvelike closure of the lower

esophagus helps to prevent high intra-abdominal pressure from

forcing stomach contents backward into the esophagus. Otherwise,

every time we walked, coughed, or breathed hard, we might expel

stomach acid into the esophagus.

Thank you

10

References : Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology,

thirteen edition.