1

Course: Medical Microbiology

Lecturer: Dr. Weam Saad

Subject: Medical Bacteriology

Medical Bacteriology

Anatomy of bacteria

All bacteria, either pathogenic or saprophytic, are unicellular organisms

that reproduce by binary fission. Most bacteria are capable of independent

metabolic existence and growth, but species of Chlamydia and Rickettsia are

obligate intracellular organisms. Bacterial cells are extremely small and

measured in microns (10-6µm). They range in size from large cells such as

Bacillus anthracis (1.0 to 1.3 µm X 3 to 10 µm) to very small cells such as

Pasteurella tularensis (0.2 X 0.2 to 0.7 µm), Mycoplasmas (atypical pneumonia

group) are even smaller, measuring 0.1 to 0.2 µm in diameter.

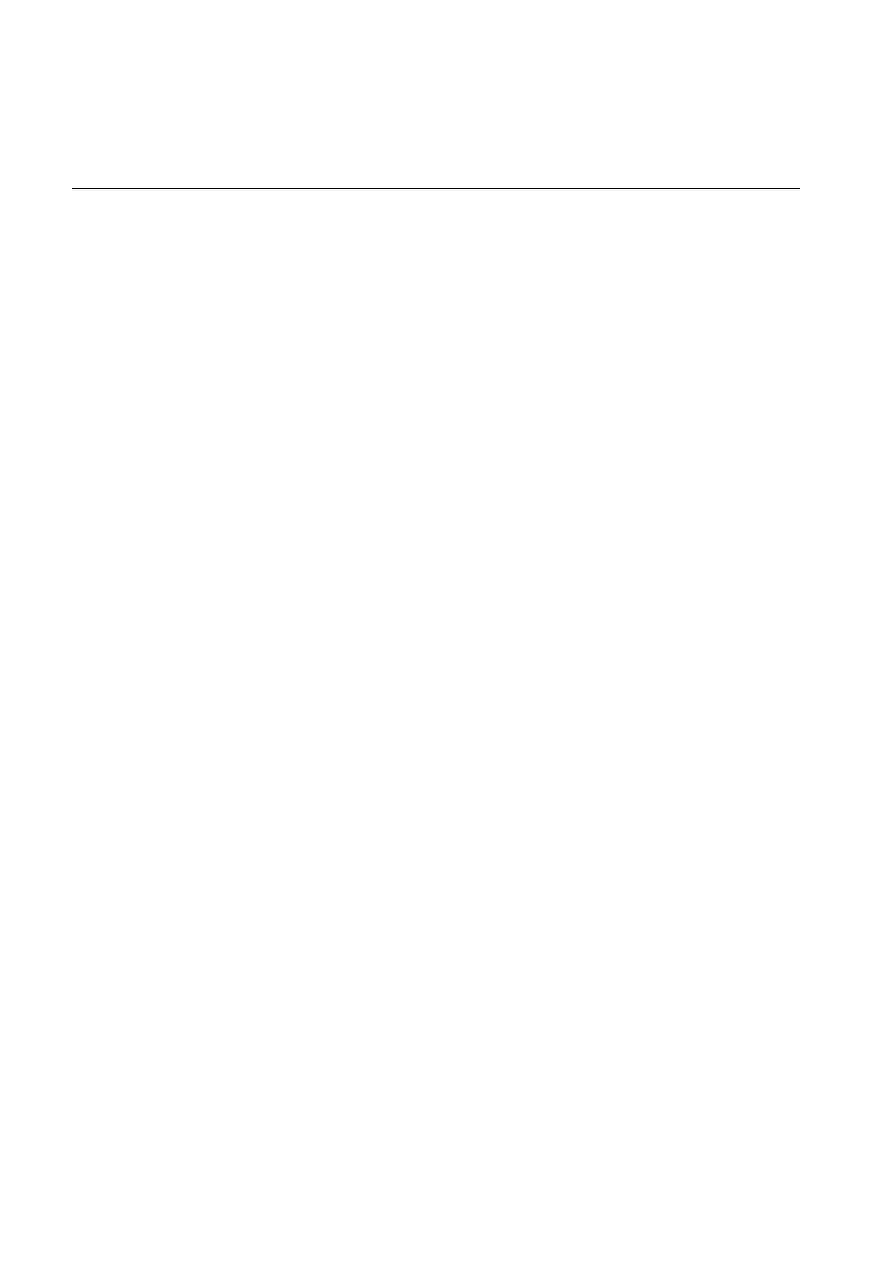

Bacteria have characteristic shapes. The common microscopic

morphologies are cocci (round cells, such as Staphylococcus aureus or

Streptococcus sp.; rods, such as Bacillus and Clostridium species; long,

filamentous branched cells, such as Actinomyces species; and comma-shaped

and spiral cells, such as Vibrio cholerae and Treponema pallidum.

The arrangement of cells is also typical of various species or groups of

bacteria. Some rods or cocci characteristically grow in chains; some, such as

Staphylococcus aureus, form grapelike clusters of spherical cells; some round

cocci form cubic packets. Bacterial cells of other species grow separately. The

microscopic appearance is important in classification and diagnosis.

2

Surface Appendages

Two types of surface appendage can be recognized: Flagella, which are

organs of movement, and Pili (in Latin =hairs), which are also known as

fimbriae ( in Latin = fringes).

Flagella occur on both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and their

presence can be useful in identification. For example, they are found on many

species of bacilli but rarely on cocci. In contrast, pili occur almost on all Gram-

negative bacteria and are found on only a few Gram-positive organisms (e.g.,

Corynebacterium renale). Some bacteria have both flagella and pili. The

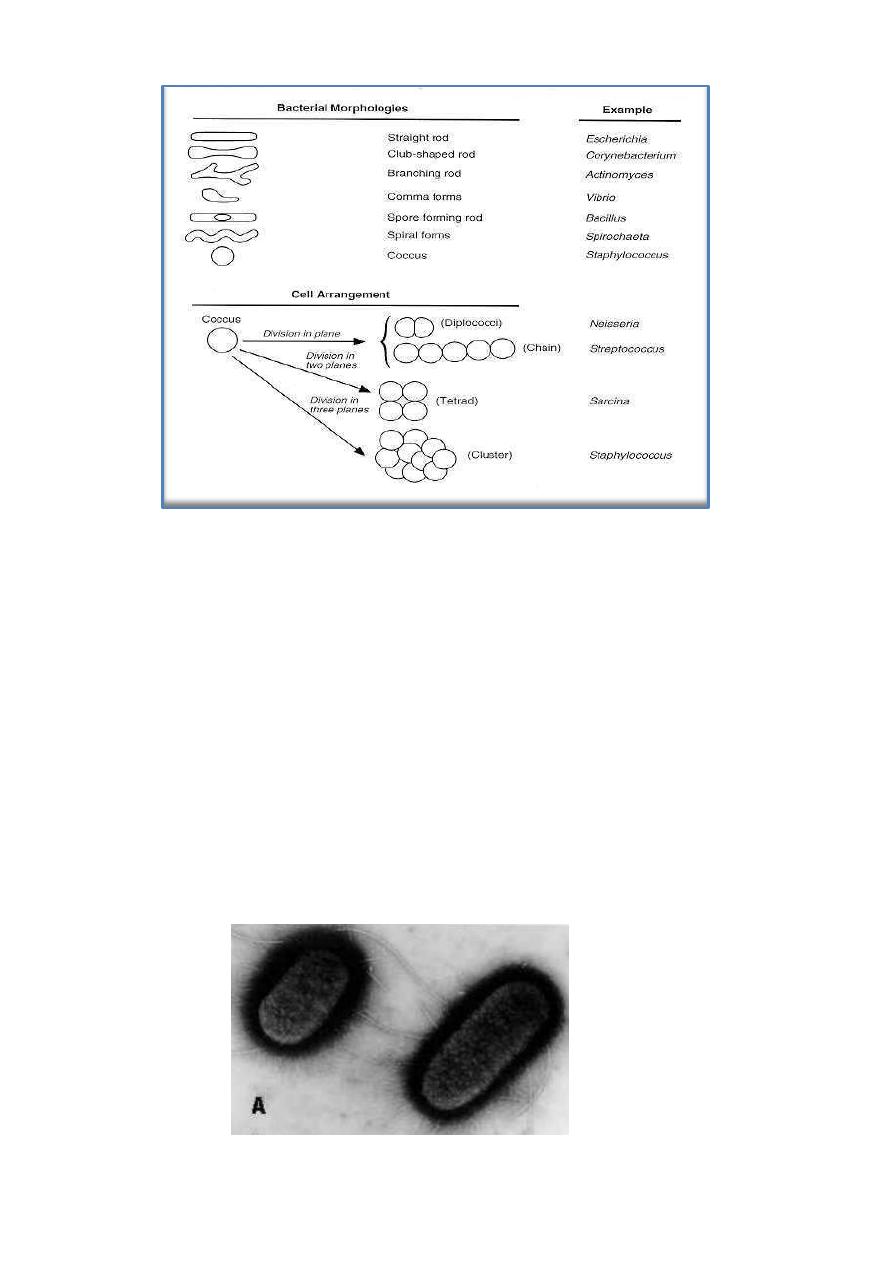

electron micrograph in Fig. below shows the characteristic wavy appearance of

flagella and two types of pili on the surface of Escherichia coli.

3

1. Flagella

Bacterial flagella are long (3 to 12 µm), filamentous surface appendages

about 12 to 30 nm in diameter. A flagellum consists of three parts:

(1) The long filament, which lies external to the cell surface.

(2) The hook structure at the end of the filament.

(3) The basal body, to which the hook is anchored and which imparts

motion to the flagellum.

The ability of bacteria to swim by flagella provides them with the

mechanical means to undergo chemotaxis (movement in response to attractant

and repellent substances in the environment).

Chemically, flagella are constructed of a class of proteins called flagellins.

Flagellins are immunogenic, these antigens are called the H antigens, which are

characteristic of a species or strain of bacteria. The species specificity of the

flagellins reflects differences in the primary structures of the proteins. Antigenic

changes of the flagella known as the phase variation of H1 and H2 occurs in

Salmonella typhimurium. The number of flagella on bacterial surface is a

characteristic for classification. Flagella formation can be inhibited by

chloramphenicol it blocks regeneration of flagella and the protein (flagellin)

synthesis.

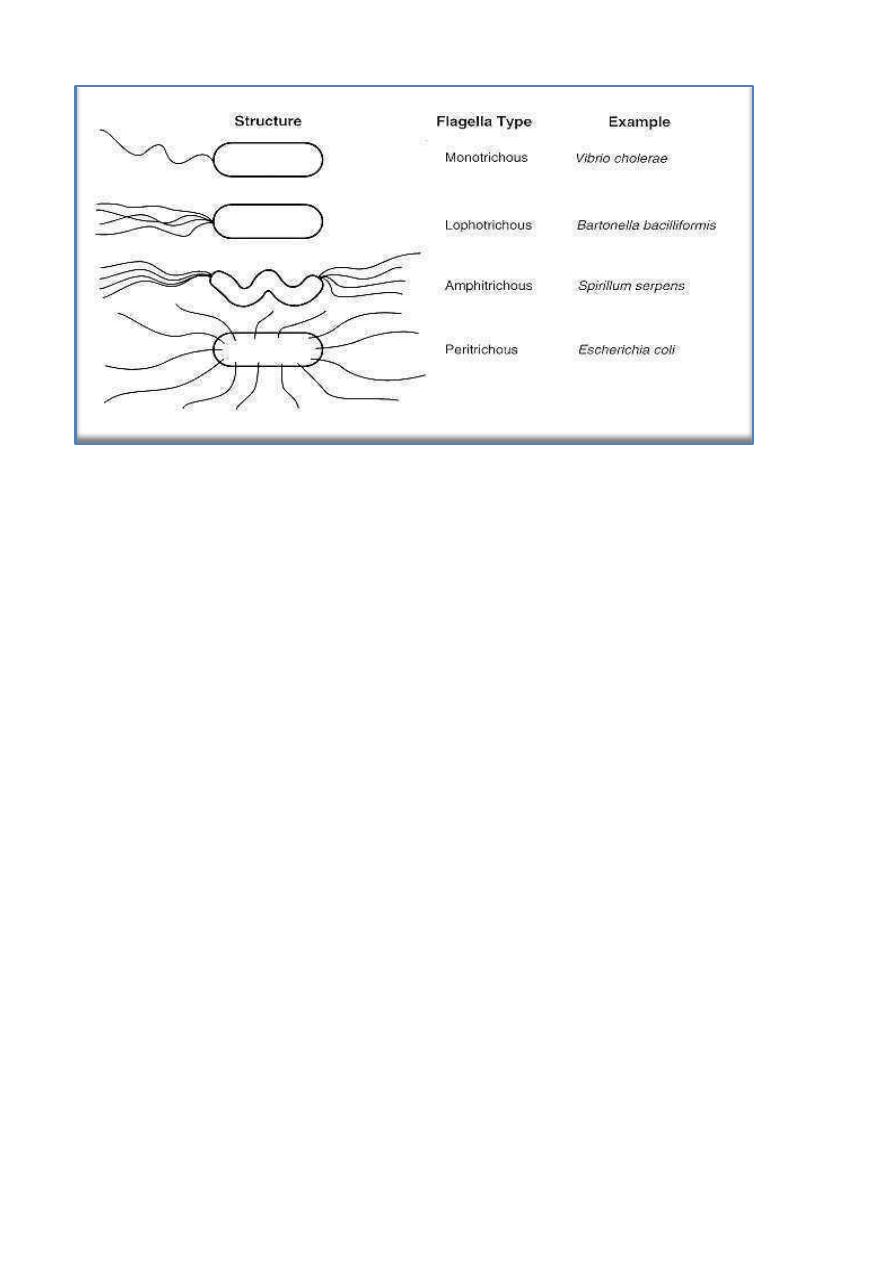

Figure below illustrates typical arrangements of flagella on or around the

bacterial surface. For example, V. cholerae has a single flagellum at one pole of

the cell (i.e., it is monotrichous), whereas Proteus vulgaris and E. coli have

many flagella distributed over the entire cell surface (i.e., they are peritrichous).

The flagella of a peritrichous bacterium must aggregate as a posterior bundle to

propel the cell in a forward direction.

4

2. Pili

The terms pili and fimbriae are usually used to describe the thin, hairlike

appendages on the surface of many Gram-negative bacteria and proteins of pili

are referred to the pilins. Pili (plural of pilus) are more rigid than flagella. In

some bacteria, such as Shigella species and E coli, pili are distributed over the

cell surface as 200 per cell.

As in E coli, pili can come in two types: short, most common pili, and sex

pili

(one to six of very long pili). The sex pili attach male to female bacteria

during conjugation.

Pili in many enteric bacteria offer the adhesive properties on the bacterial

cells, enabling them to adhere to various epithelial surfaces and to the RBCs

(causing hemagglutination). These adhesive properties play an important role in

bacterial pathogenesis; colonization of epithelial surfaces and are therefore

called colonization factors.

5

Surface Layers

1. Capsules and Loose Slime

Some bacteria form capsules, they are thick layer of viscous gel. Capsules

may be up to 10 µm thick. Some organisms lack a well-defined capsule but

have loose slime layers external to the cell wall or cell envelope. The hemolytic

Streptococcus mutans, the primary organism found in dental plaque is able to

synthesis a large extracellular mucoid glucans from sucrose.

Not all bacterial species produce capsules; the capsules of encapsulated

pathogens are often important determinants of virulence. In both groups, Gram-

positive and Gram-negative bacteria; most capsules are composed of high

molecular-weight polysaccharides outside the cell wall or envelope except the

capsule of Bacillus anthracis (the pathogen of anthrax), it is unusual in that it is

composed of a g-glutamyl polypeptide. Mutation can cause loss of enzymes

involved in the biosynthesis of the capsular polysaccharides can result change

from the smooth-to-rough as seen in the pneumococci.

The exact function of capsule is resistance to phagocytosis and protection

of the bacterial cell against the host defenses during invasion. Some bacterial

capsules work as main virulence factor.

2. Cell Wall

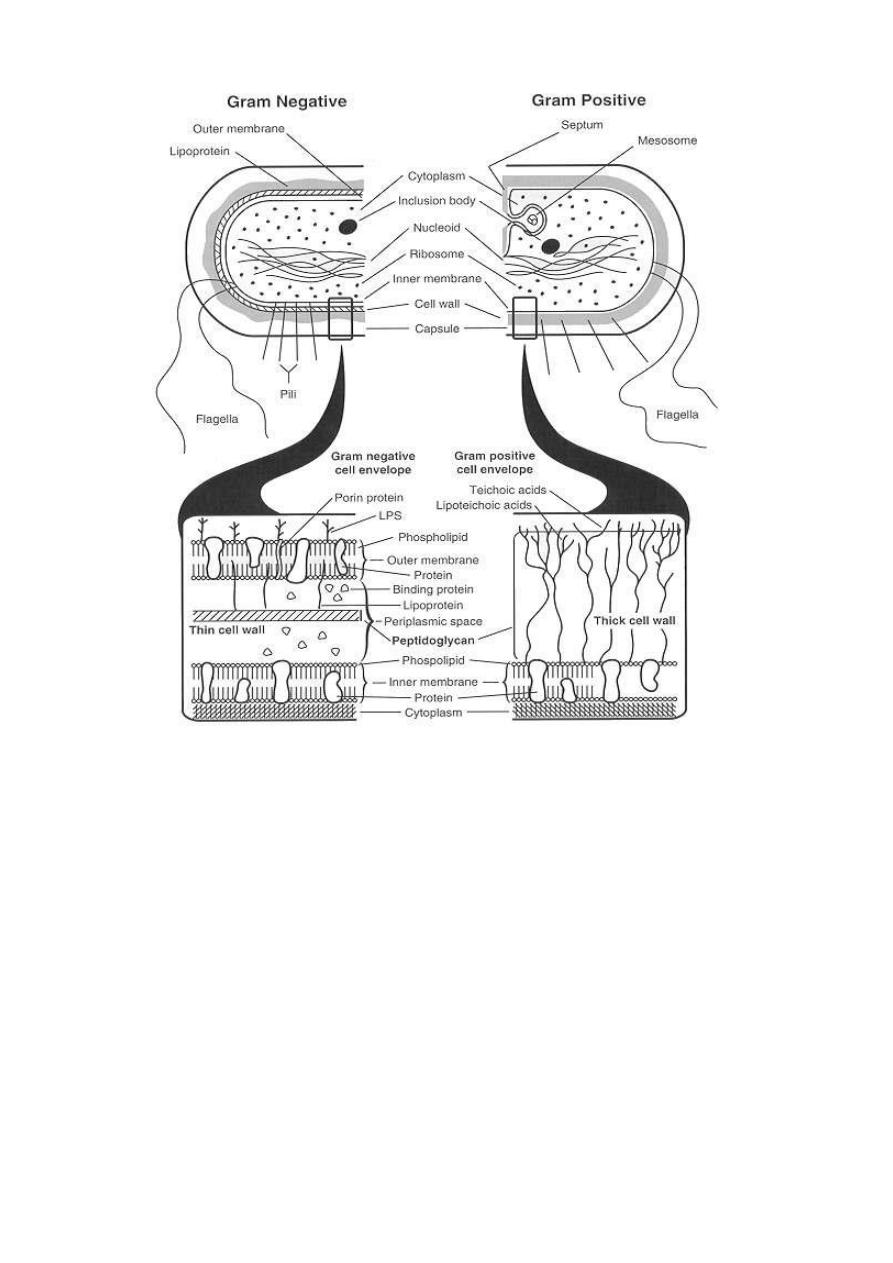

The Gram stain differentiates bacteria into Gram-positive and Gram-

negative groups. Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms differ in the

structures of their cell walls, see figure below.

Most Gram-positive bacteria have a thick (about 20 to 80 nm), cell wall

composed of peptidoglycan (also known as mucopeptide or murein). In thick

cell walls, some other cells have other wall polymers (such as the teichoic acids,

polysaccharides, and peptidoglycolipids) are attached to the peptidoglycan. The

peptidoglycan layer in Gram-negative bacteria is thin (about 5 to 10 nm thick).

The basic differences in surface structures of Gram-positive and Gram-

negative bacteria explain the results of Gram staining.

6

Peptidoglycan

Unique composition in all prokaryotic cells (except for mycoplasmas) is

the peptidoglycan, this layer help in mechanical protection and there are

specific enzymes involved in its biosynthesis. These enzymes are target sites for

inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis by specific antibiotics. The primary

chemical structures of peptidoglycans consist of a polymer backbone of

disaccharides of N-acetylmuramyl-N-acetylglucosamine and are linked through

the carboxyl group by amide linkage of muramic acid residues.

There are two groups of bacteria that lack the peptidoglycan, the

Mycoplasma species (causes atypical pneumonia and some genitourinary tract

7

infections) and the L-forms. The mycoplasmas and L-forms are all Gram-

negative and insensitive to penicillin.

Teichoic Acids

The teichoic acids are found only in some Gram-positive bacteria (such as

Staphylococci, Streptococci, Lactobacilli, and Bacillus spp); they are not found

in gram- negative bacteria. Teichoic acids are polyol phosphate polymers, with

either ribitol or glycerol linked by phosphodiester bonds. It can act as a specific

antigenic determinant.

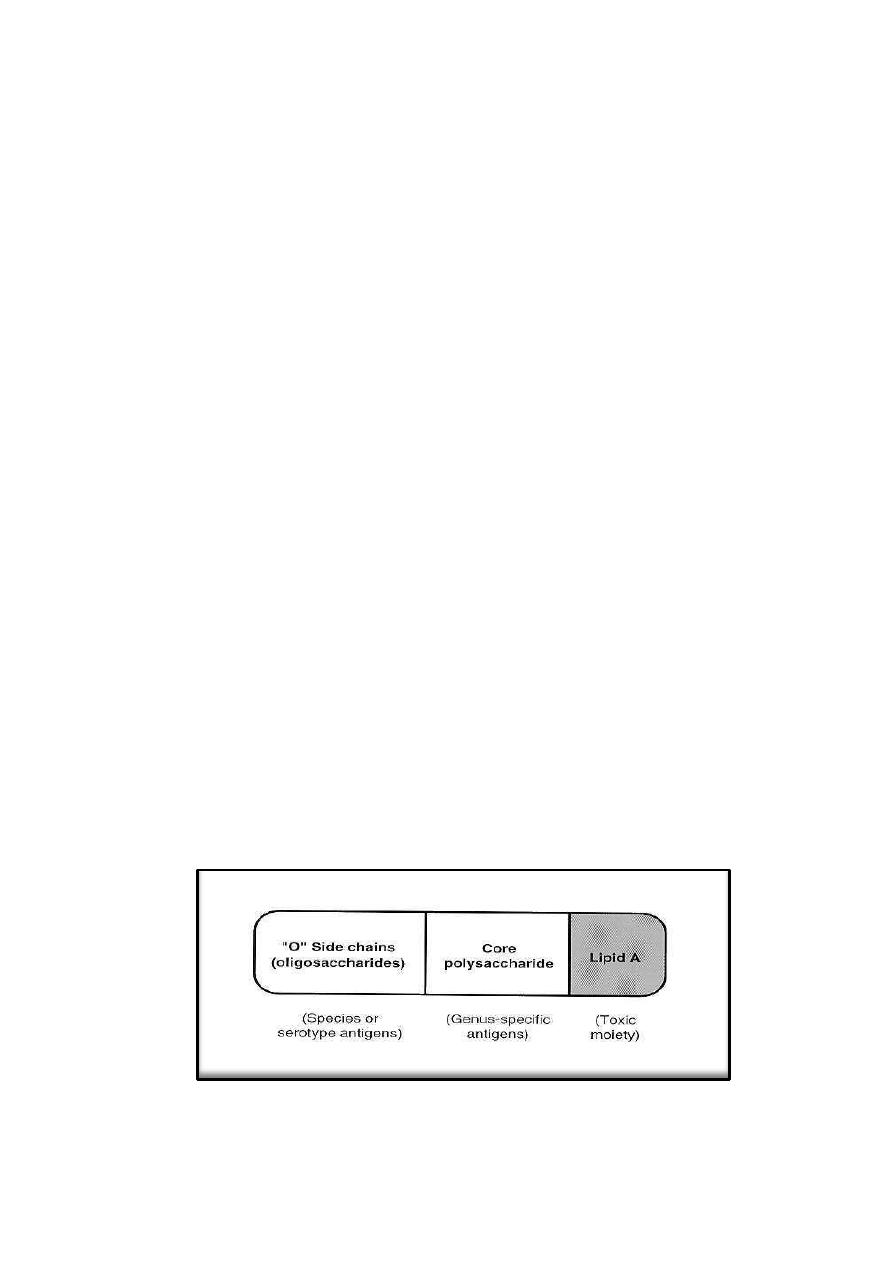

Lipopolysaccharides

A characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria is the lipopolysaccharide (LPS),

only one Gram-positive organism, Listeria monocytogenes, has been found to

contain LPS. The LPS are also called endotoxins, they are cell-bound, heat-

stable toxins and differ from heat-labile, protein exotoxins secreted into culture

media. Endotoxins possess an array of powerful biologic activities and play an

important role in the pathogenesis of many Gram-negative bacterial infections.

In addition LPS is pyrogenic and causes endotoxic shock, can activate

macrophages and complement system, it is mitogenic for B lymphocytes,

induces interferon production, causes tissue necrosis and tumor regression, and

has adjuvant properties. The endotoxic properties of LPS is due to the lipid A

components. Usually, the LPS molecules have three regions: The lipid A

attached to the core composed of polysaccharide chains which are linked to the

O-antigens responsible for serologic specificity of the Gram-negative bacteria.

8

Intracellular Components

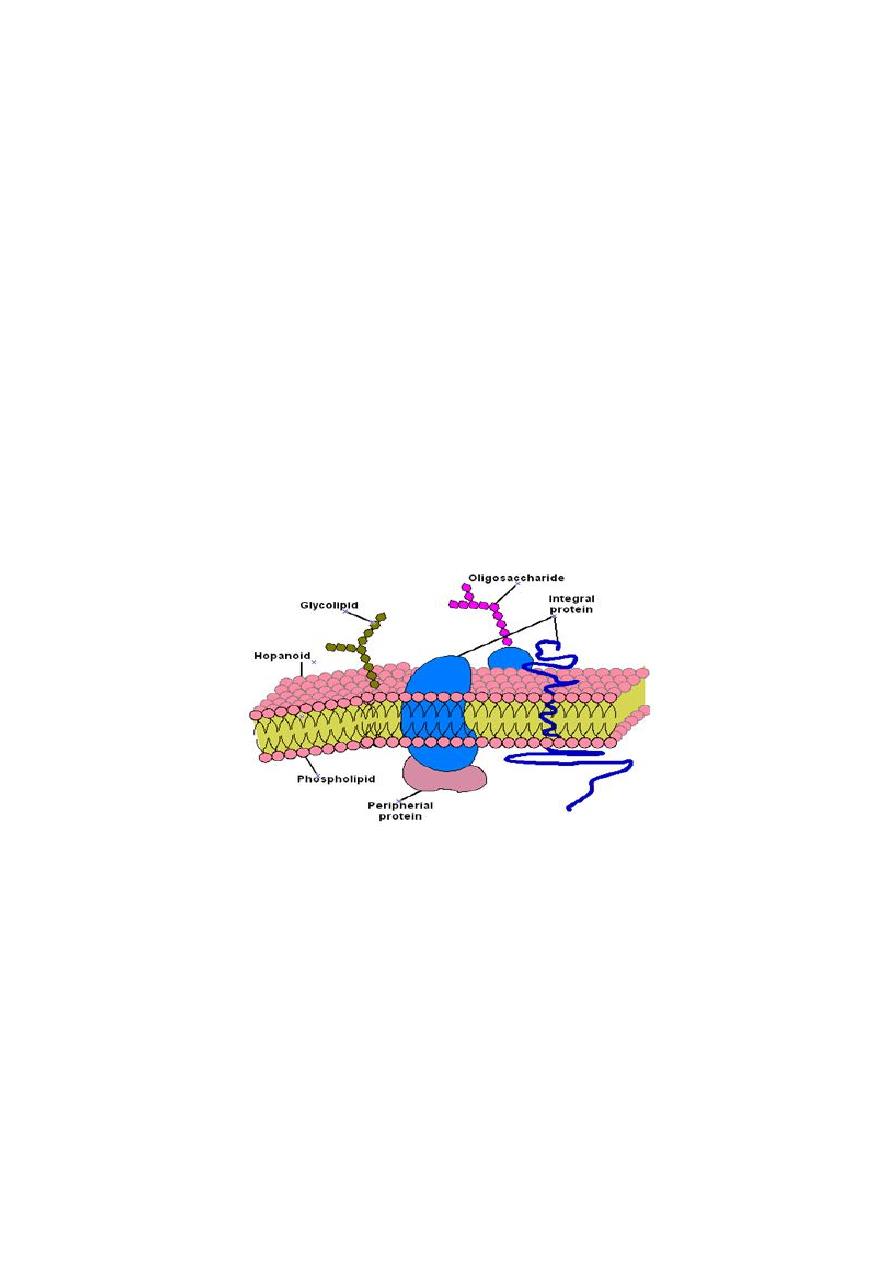

1. Plasma (Cytoplasmic) Membranes

Bacterial plasma membranes is similar to eukaryotic plasma membranes in

function, are referred to cytoplasmic or protoplast membranes, they are

composed primarily of proteins and lipids (phospholipids). Protein-to-lipid

ratios of bacterial plasma membranes are approximately 3:1, close to those for

mitochondrial membrane.

Plasma membranes are the site of active transport, respiratory chain

components, energy-transducing systems, the ATPase of the proton pump, and

membrane stages in the biosynthesis of phospholipids, peptidoglycan, LPS, and

capsular polysaccharides. The bacterial cytoplasmic membrane is a

multifunction structure similar to mitochondrial transport and biosynthetic

functions of eukaryotic cells. The plasma membrane is also the anchoring site

for the bacterial DNA.

2. Mesosomes

The mesosomes are tubular-vesicular membrane structures found in Gram-

positive bacteria which are formed by an invagination of the plasma membrane.

These structures equivalent to bacterial mitochondria; and may be related to

events in the cell division cycle.

9

3. Other Intracellular Components

Ribosomes of the 70S type; ribonucleoprotein particles are not arranged on a

membranous rough endoplasmic reticulum as they are in eukaryotic cells, they

are found in the cytoplasm.

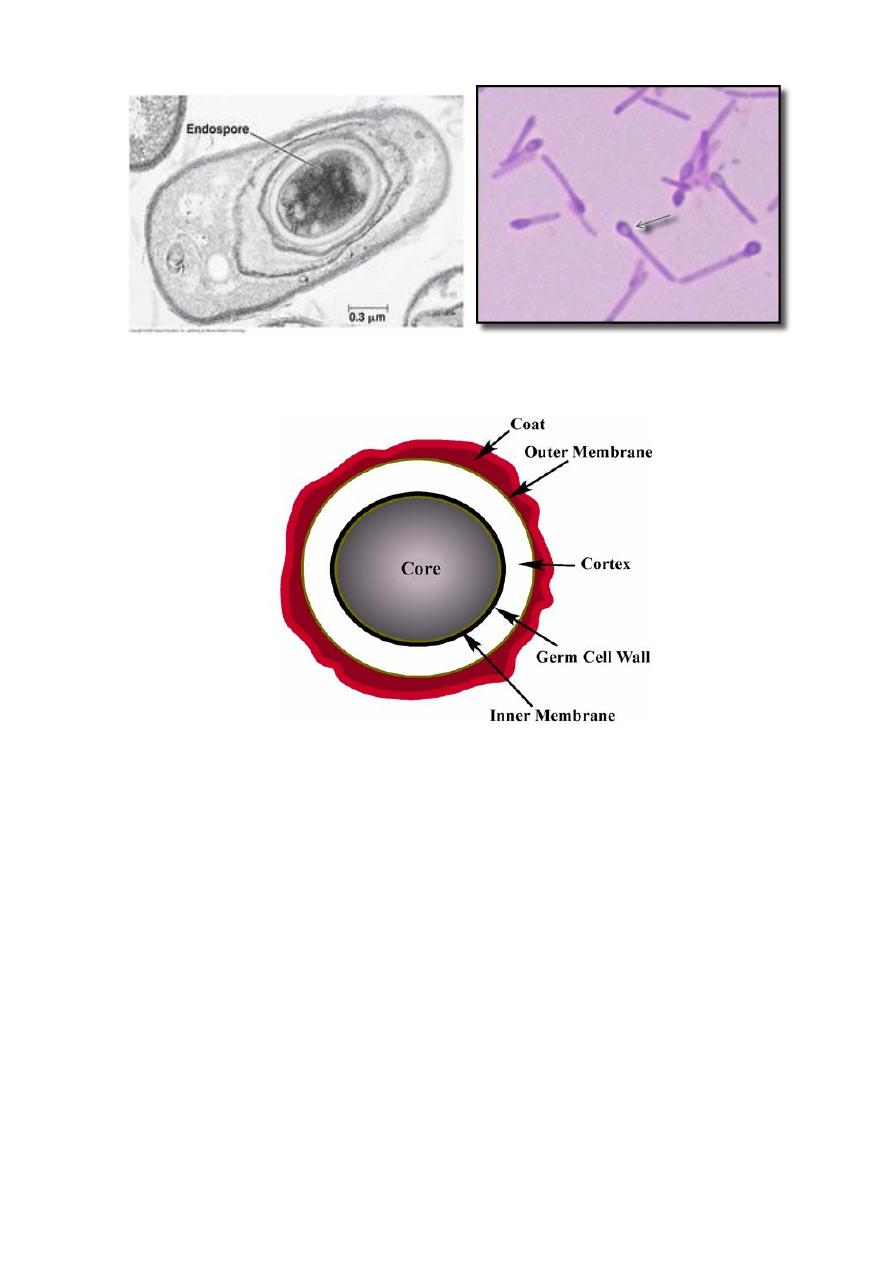

Endospores are highly heat-resistant, dehydrated cells formed

intracellularly in some bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium. Sporulation, is

the process of forming endospores because of many biochemical and

morphologic changes begins in the stationary phase of the vegetative cell cycle

due to decrease nutrients (sources of carbon and nitrogen). Also formation of

unusual peptidoglycan which contains calcium dipicolinate, help in resistance

to heat, radiation, pressure, and organic solvents.

The spore protoplast, or core, contains a complete chromosome,

ribosomes, and energy generating components. During germination, the spore

wall becomes the vegetative cell wall and cortex will be released.

10

Genetic Information In Bacteria (Genome)

Genetic material, genome or the genotype replicate in the parental organism

to give the daughter organism a copy of the genetic material. Expression of

genetic material determines the observable characteristics (phenotype) of the

organism. Some bacteria have the DNA chromosome as the only genetic

material (genome) in bacterial cells, like Escherichia coli. Other bacteria have

additional genetic materials, such as plasmids and bacteriophages.

11

1. Chromosomal DNA

Bacterial genomes differ in size from about 0.4 x 109 to 8.6 x 109 daltons

(Da), some of the smallest found in the obligate parasites (Mycoplasma) and the

largest in Myxococcus. The amount of DNA in the genome determines the

maximum amount of information that it can encode. Most bacteria have a

haploid genome, a single chromosome consisting of a circular, double stranded

DNA molecule. However linear chromosomes have been found in Gram-

positive Borrelia and Streptomyces spp.,

The typical genome to be studied is the E coli genome, it is sufficient to

code for thousand polypeptides of average size (40 kDa or 360 amino acids),

the DNA is supercoiled and tightly packaged in the bacterial nucleoid. The

time required for replication of the entire chromosome is about 40 minutes,

which is approximately twice the shortest division time for this bacterium.

The replication of chromosomal DNA in bacteria is complex and involves

many different proteins, in rapidly growing bacteria a new round of

chromosomal replication begins before an earlier round is completed. Thus, the

chromosome is replicating at more than one point. Bacterial chromatin does not

contain basic histone proteins, but low-molecular-weight polyamines and

magnesium ions may give a function similar to that of eukaryotic histones.

2. Plasmids

Plasmids are extrachromosomal genetic elements in bacteria. They are

smaller than the bacterial chromosome. Plasmids usually encode properties that

are not essential for bacterial viability, and replicate independently of the

chromosome.

Most plasmids are supercoiled, circular, double-stranded DNA molecules,

The Large plasmids (Conjugative plasmids) promote transfer of the bacterial

chromosome from the donor bacterium to other recipient bacteria are also called

fertility plasmids. The small plasmids are usually non-conjugative.

Many plasmids control medically important properties of pathogenic

bacteria, including resistance to antibiotics, production of toxins, and synthesis

of cell surface structures required for adherence or colonization. Plasmids that

12

determine resistance to antibiotics are called R plasmids (or R factors) like the

plasmid in Staphylococcus aureus. Some toxins encoded by plasmids include

heat-labile and heat-stable enterotoxins of E. coli, exfoliative toxin of

Staphylococcus aureus, and tetanus toxin of Clostridium tetani. Some plasmids

have no recognizable effects on the bacterial cells that have them.

3. Bacteriophages

Bacteriophages (bacterial viruses, phages, viruses that infect bacteria) are

infectious agents for bacteria that live as obligate intracellular parasites inside

bacteria, consist proteins plus nucleic acid (DNA or RNA, but not both). The

proteins of the phage particle form a protective shell (capsid) surrounding the

tightly packaged nucleic acid genome.

Phage genomes are different in size, consist of double-stranded DNA,

single-stranded DNA, or RNA. Phage genomes, like plasmids, encode functions

required for the replication of virus in bacteria, they also encode capsid proteins

and nonstructural proteins required for phage life cycle.

Bacteriophages attached on bacteria surface under electron

microscope

For example of phages responsible of virulence: the production of

diphtheria toxin by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, erythrogenic toxin by

Streptococcus pyogenes (group A beta-hemolytic streptococci), botulinum toxin

by Clostridium botulinum, and Shiga-like toxins by E. coli.

13

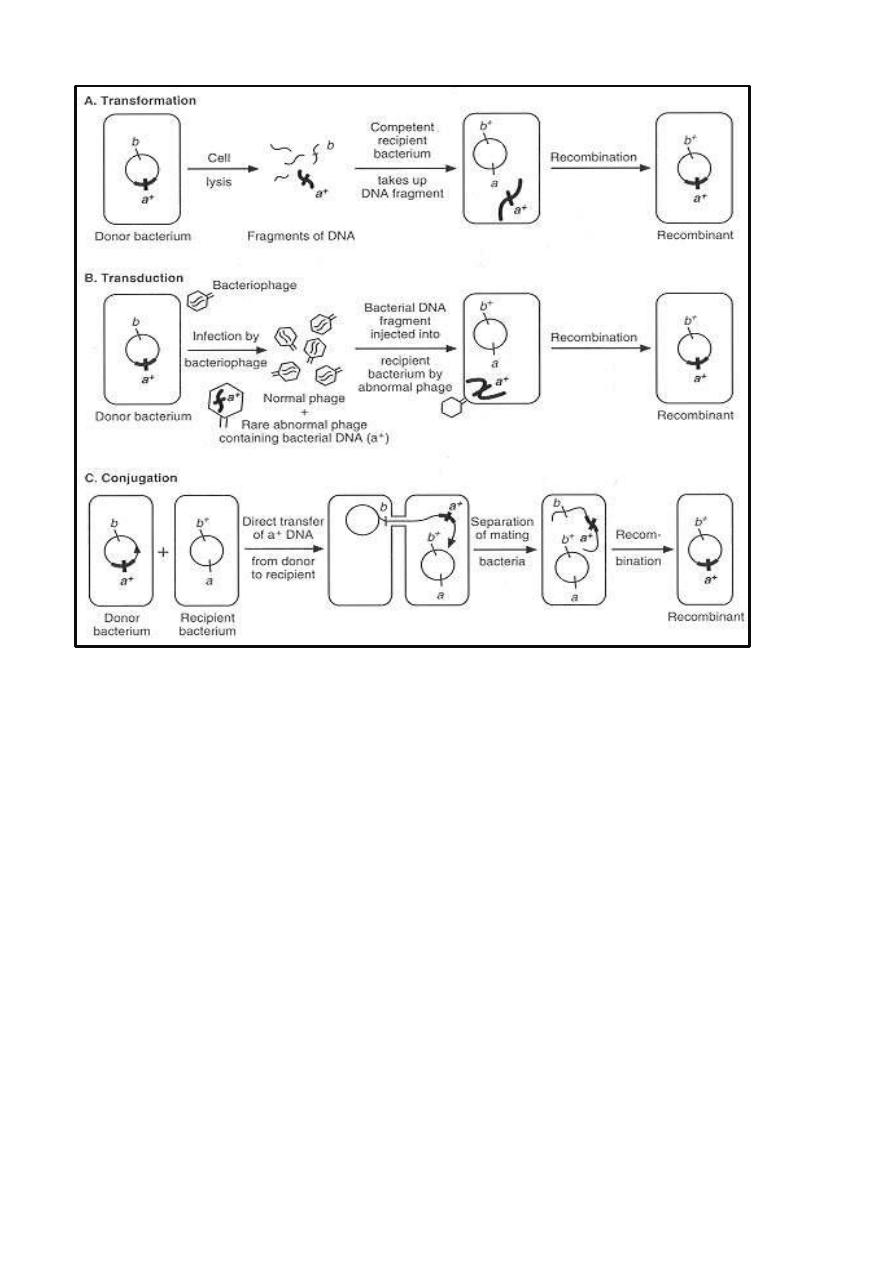

Exchange of Genetic Information

A phenomena of medical importance that involve exchanges of genetic

information or genomic rearrangements include the rapid antibiotic resistance

plasmids, flagellar phase variation in some bacteria like Salmonella, and

antigenic variation of surface antigens like in Neisseria and Borrelia. These

processes involve Transformation, transduction, and conjugation

1. Transformation

In transformation, pieces of DNA (at least 500 nucleotides in length)

released from donor bacteria are taken up directly from the extracellular

environment by other recipient bacteria. Recombination occurs between single

molecules of transforming DNA and the chromosomes of recipient bacteria.

Transformation was discovered in Streptococcus pneumoniae and occurs in

other bacterial genera including Haemophilus, Neisseria, Bacillus, and

Staphylococcus.

2. Transduction

In transduction, bacteriophages function as vectors to carry a small segment

of the bacterial genome (DNA genes) from donor bacteria into other recipient

bacteria by infection. When phage infects a recipient cell, expression of the

transferred donor genes occurs and complete transduction is characterized by

production of new proteins (donor phenotype). In abortive transduction the

donor DNA fragment does not replicate.

3. Conjugation

In conjugation, direct contact between the donor and recipient bacteria leads

to establishment of a cytoplasmic bridge between them and transfer of part or

all of the donor genome to the recipient. Donor bacteria must have conjugative

plasmids called fertility+ plasmids, sex plasmids or F factor, e.g. F plasmid of

E. coli.

14

Recombination DNA and Gene Cloning (Genetic Engineering)

Recombination involves breakage and joining of DNA molecules to form

hybrid, recombinant molecules. Several kinds of recombination have been

identified by the help of specific enzymes that act on DNA (e.g., exonucleases,

endonucleases, polymerases, ligases) participate in recombination .

Many methods are available to make hybrid DNA molecules in vitro

(recombinant DNA). Cloned genes can be expressed in appropriate host cells,

and the phenotypes that they show can be determined.

Applications of DNA cloning are expanding rapidly in all fields of

biology and medicine :

15

In medical genetics such applications range from the prenatal diagnosis of

inherited human diseases to the characterization of oncogenes and their

roles in carcinogenesis .

Pharmaceutical applications include production from cloned human genes

of biologic products with therapeutic purposes, such as hormones,

interleukins, and enzymes .

Applications in public health and laboratory medicine include

development of vaccines to prevent specific infections by polymerase

chain reaction (PCR). The PCR process uses oligonucleotide primers and

DNA polymerase to amplify specific target DNA sequences during

synthesis in vitro, help to detect target DNA sequences in clinical

specimens with great sensitivity.