Diarrhea

Epidemiology of Childhood Diarrhea

Diarrheal disorders in childhood account for a large proportion (18%) of childhood

deaths, with an estimated 1.5 million deaths per year globally, making it the second most

common cause of child deaths worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) and

UNICEF estimate that almost 2.5 billion episodes of diarrhea occur annually in children

<5 yr of age in developing countries, with more than 80% of the episodes occurring in

Africa and South Asia (46% and 38%, respectively)

The decline in diarrheal mortality, despite the lack of significant changes in incidence, is

the result of preventive rotavirus vaccination and improved case management of diarrhea,

as well as improved nutrition of infants and children. These interventions have included

widespread home- and hospital-based oral rehydration therapy and improved nutritional

management of children with diarrhea.

The term diarrheal disorders is more commonly used to denote infectious diarrhea

in public health settings, although several noninfectious causes of GI illness with

vomiting and/or diarrhea are well recognized

Definition:

Diarrhea is defined as increased total daily stool output, its usually associated with

increased stool water content, for infant and children this would result in stool output

greater than 10 gm/kg/24 hours.

Pathophysiology

The basis for all diarrhea is disturbed intestinal solute transport; water movement across

intestinal is passive and is determined by both active and passive fluxes of solute,

particularly sodium, chloride and glucose. The pathogenesis of most episodes of diarrhea

can be explained by secretory, osmotic or motility abnormalities or a combination of

these. Secretory diarrhea is often caused by a secretagogue, such as cholera toxin,

binding to a receptor on the surface epithelium of the bowel and thereby stimulating

intracellular accumulation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Diarrhea not associated

with exogenous secretagogue may also have a secretory component ( e.g. congenital

microvillus inclusion disease). Secretory diarrhea tend to be watery and of large volume

and generally persist even when no feeding are given by mouth, it has normal osmolarity

with ion gap less than 100 mosm/kg and no stool leukocytes

Ion gap = stool osmolarity –[{stool Na + stool K}x 2]

E.g. ; cholera, toxigenic E. coli, carcinoid, vip, neuroblastoma, congenital chloride

diarrhea, clostridium difficile, cryptosporidiosis (AIDS)

Osmotic diarrhea occur after ingestion of a poorly absorbed solute. The solute may be one

that is normally not well absorbed (e.g. magnesium, phosphate, lactolose or sorbitol), or

one that is not well absorbed because of a disorder of the small bowel (e.g. lactose with

lactase deficiency or glucose with rotavirus diarrhea), also with laxative abuse this form

of diarrhea is usually of lesser volume than secretory diarrhea and stops with fasting, The

stool is watery, acidic with reducing substances and ion gap is > 100 mosm/kg, stool

osmolality is > 50 mosm, and there is increased breath hydrogen and no stool leukocyte.

Acute diarrhea

causes:

1. common:

Gastroenteritis, systemic infection (parenteral diarrhea), antibiotic associated and food

poisoning in older children.

2. rare:

Primary disaccharidase deficiency, hirschsprung toxic colitis, adrenogenital syndrome,

toxic ingestion and hyper thyroidism.

Gastroenteritis:

Mean infection of the gastrointestinal tract, it is caused by a wide variety of

enteropathogens, including bacteria, viruses and parasites. Gastroenteritis is due to

infection acquired through the feco-oral route or by ingestion of contaminated food or

water. Enteropathogens that are infectious in a small inoculum (Shigella, Escherichia

coli, noroviruses, rotavirus, Giardia lamblia, Cryptosporidium parvum, Entamoeba

histolytica) can be transmitted by person-to-person contact, whereas others such as

cholera are generally a consequence of contamination of food or water supply

. Salmonella, Shigella, and, most notably, the various diarrhea-producing E. coli

organisms are the most common pathogens in developing countries . Clostridium

difficile (by toxin production) is linked to antibiotic-associated diarrhea and

pseudomembranous colitis

PATHOGENESIS OF INFECTIOUS DIARRHEA

Enteropathogens elicit noninflammatory diarrhea through enterotoxin production

by some bacteria, destruction of villus (surface) cells by viruses, adherence by

parasites, and adherence and/or translocation by bacteria. Inflammatory diarrhea is

usually caused by bacteria that directly invade the intestine or produce cytotoxins with

consequent fluid, protein, and cells (erythrocytes, leukocytes) that enter the intestinal

lumen. Generally inflammatory diarrhea is associated with aeromonas, campylobacter

jejuni, clostridium difficile, enteroenvasive E.coli, shigatoxin-producing E.coli,

salmonella, shigella and yersinia. Non inflammatory diarrhea may be caused by

enteropathogenic E.coli, enterotoxigenic E.coli, vibrio cholera. Some enteropathogens

possess more than one virulence property.

RISK FACTORS FOR GASTROENTERITIS

Major risks include environmental contamination and increased exposure to

enteropathogens. Additional risks include young age, immune deficiency, measles,

malnutrition, and lack of exclusive or predominant breast-feeding. Malnutrition

increases severalfold the risk of diarrhea and associated mortality.The risks are

particularly higher with micronutrient malnutrition; in children with vitamin A

deficiency, the risk of dying from diarrhea, measles, and malaria is increased by 20–

24%. Zinc deficiency increases the risk of mortality from diarrhea, pneumonia, and

malaria by 13–21%.\

CLINICAL MANIFESTATION OF DIARRHEA

include: asymptomatic infection, abdominal cramps, vomiting, watery diarrhea,

bloody diarrhea and extra intestinal manifestation of the infection (e.g. hypotonia

from clostridium botulinum, hemolytic anemia from infection with E. coli or

shigella).

Several organisms, including Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter jejuni, Yersinia

enterocolitica, enteroinvasive E. coli, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus, produce diarrhea

that can contain blood as well as fecal leukocytes in association with abdominal

cramps, tenesmus, and fever; these features suggest bacterial dysentery.

COMPLICATIONS

dehydration with associated complications.

-

-malnutrition and complications such as secondary infections and micronutrient

deficiencies (iron, zinc).

-

Bacteremias

-

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of gastroenteritis is based on clinical recognition, and confirmation by

appropriate laboratory investigations, if indicated.

CLINICAL EVALUATION OF DIARRHEA.

includes:

The evaluation of a child with acute diarrhea

Assess the degree of dehydration and acidosis and provide rapid resuscitation and

rehydration with oral or intravenous fluids as required .

Obtain appropriate contact or exposure history. This includes information on

exposure to contacts with similar symptoms, intake of contaminated foods or water,

child-care center attendance, recent travel to a diarrhea-endemic area, and use of

antimicrobial agents

Clinically determine the etiology of diarrhea for institution of prompt antibiotic

therapy, if indicated. Although nausea and vomiting are nonspecific symptoms, they

are indicative of infection in the upper intestine. Fever is suggestive of an

inflammatory process but also occurs as a result of dehydration or co-infection (e.g.,

urinary tract infection, otitis media). Fever is common in patients with inflammatory

diarrhea. Severe abdominal pain and tenesmus are indicative of involvement of the

large intestine and rectum. Features such as nausea and vomiting and absent or low-

grade fever with mild to moderate periumbilical pain and watery diarrhea are

indicative of small intestine involvement and also reduce the likelihood of a serious

bacterial infection

STOOL EXAMINATION;

Stool specimens should be examined for mucus, blood, and leukocytes. Fecal

leukocytes are indicative of bacterial invasion of colonic mucosa. In endemic areas,

stool microscopy must include examination for parasites causing diarrhea, such as G.

lamblia and E. histolytica

XTAG GPP is an FDA-approved gastrointestinal pathogen panel

using multiplexed nucleic acid technology that detects Campylobacter,

C. difficile, toxin A/B, E. coli 0157, enterotoxigenic E. coli, Salmonella,

Shigella, Shiga-like toxin E. coli, norovirus, rotavirus A, Giardia, and Cryptosporidium.

Stool cultures should be obtained as early in the course of disease as possible from

children with bloody diarrhea in whom stool microscopy indicates fecal leukocytes;

in outbreaks with suspected hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS); and in

immunosuppressed children with diarrhea.The yield and diagnosis of bacterial

diarrhea can be significantly improved by using molecular diagnostic procedures

such as PCR. Blood can be send for assessment of Hb level, Bl urea and serum

electrolyte like Na and K.

Assessment of dehydration

In all children with diarrhea, decide if dehydration is present and give appropriate

treatment.

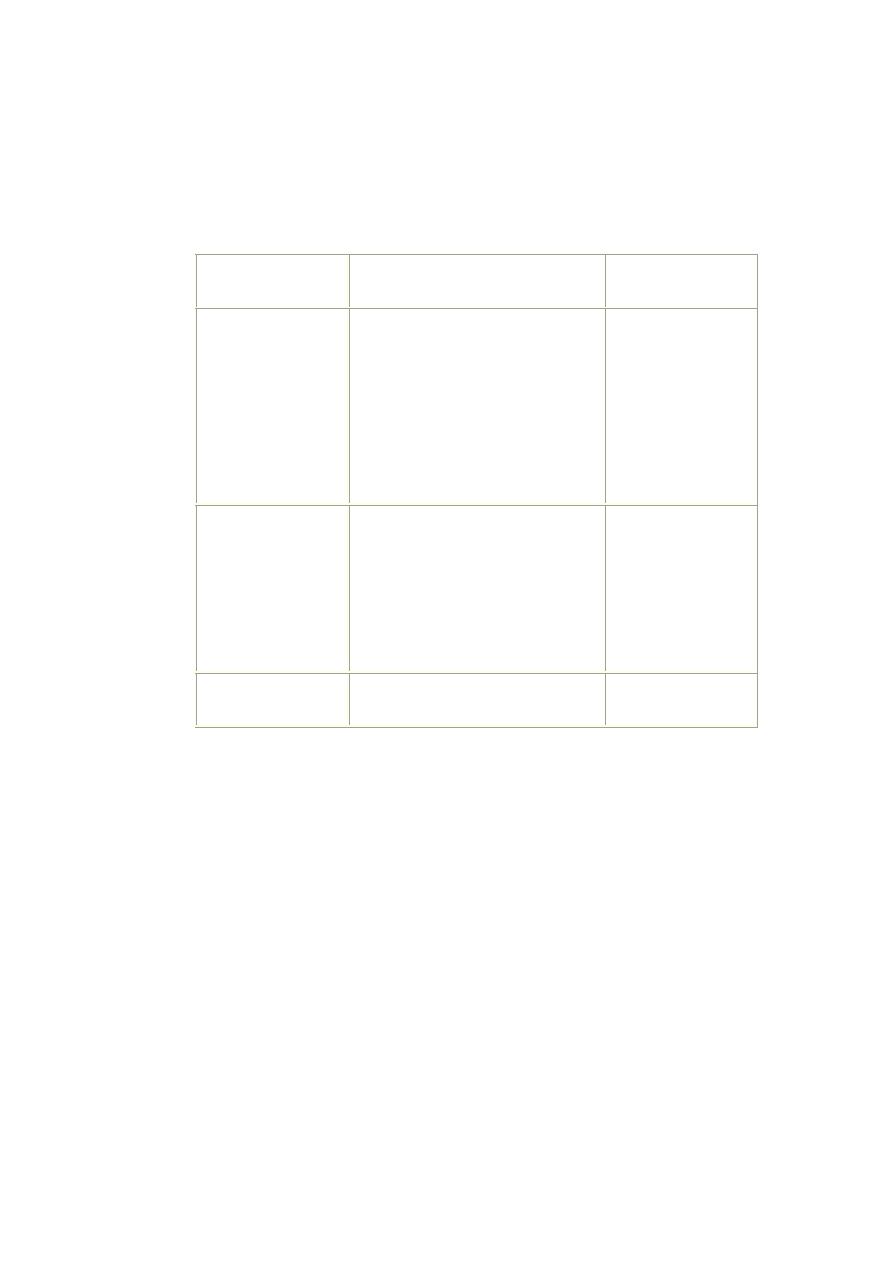

Classification of the severity of dehydration in children with diarrhea:

Treatment

Signs or symptoms

Classification

Treatment plan C

Two or more of the following

signs:

-lethargy/unconsciousness

- tear drops not present.

- sunken eyes.

- unable to drinks /poorly.

-skin pinch goes back very slowly

( ≥2 seconds)

-mouth is very dry

Sever dehydration

Treatment plan B

Two or more of the following

signs:

- restlessness, irritability.

-tear drops not present.

- sunken eyes.

- drinks eagerly.

- skin pinch goes back slowly

-Mouth is dry

Some dehydration

Treatment plan A

Not enough signs to classify as

some or severe dehydration.

No dehydration

TRETMENT:

Diarrhea treatment plan A:

Treat diarrhea at home

- Explain the 4 rules of home treatment:

1. give extra fluid (as much as the child will take)

Tell the mother:

- breastfeed frequently and for longer at each feed.

- if the infant is less than 6 m. old , give ORS or clean water in addition to breastmilk.

- if the child is older, give one or more of the followings: ORS solution, food-based fluids

(such as soup, rice water, and yoghurt drinks), or clean water.

Teach the mother how to mix and give ORS. Give the mother 2 packets of ORS to use

at home. Tell her to mix one packet with one litter of water

Show the mother how much fluid to give in addition to the usual fluid intake:

Up to 2 years 50 to 100 ml after each loose stool

2 years or more 100 to 200 ml after each loose stool

Tell the mother to:

- give the frequent small sips from a cup. or by cup and spoon

- if the child vomits, wait 10 minutes. Then continue, but more slowly.

- continue giving extra fluid until the diarrhea stop.

2. give zinc supplements

There is strong evidence that zinc supplementation in children with diarrhea in

developing countries leads to reduce duration and severity of diarrhea and could

potentially prevent 300,000 deaths. WHO and UNICEF recommend that all children

with acute diarrhea in at-risk areas should receive oral zinc in some form for 10–14

days during and after diarrhea (10 mg/day for infants <6 mo of age and 20 mg/day for

those >6 mo). In addition to improving diarrhea, administration of zinc in community

settings leads to increased use of ORS and reduction in the use of antimicrobials.

Tell the mother how much zinc to give:

Up to 6 months 1/2 tablet (10 mg) per day for 10-14 days.

6 months and more 1 tablet (20 mg) per day for 10-14 days.

Show the mother how to give the zinc supplements:

- infants, dissolve the tablet in a small amounts of clean water, expressed milk or ORS in

a small cup or spoon.

- older children, tablet can be chewed or dissolved in a small amount of clean water in a

cup or spoon.

Remind the mother to give the zinc supplements for the full 10-14 days.

3. continue feeding.

• FEEDING IN DIARRHEA:

o

Children should continue to be fed during diarrhea.

o

. Milk should not be diluted with water during any phase of acute diarrhea.

o

Milk can also be given as milk cereal mixture e.g. milk-rice mixture.

o

To make foods-energy dense some of preparation are:-

- Mashed banana with milk or curd

- Mashed potatoes with oil.

o

–fresh cooked vegetable

A child who is recovering from diarrhoea needs an extra meal every day for at least 2 W.

Breast feeding should be continued uninterrupted even during rehydration with ORS.

4. when to return

■ when her baby develop repeated vomiting.

■ develop fever.

■ become irritable and restless.

■ has blood in stool.

ORAL REHYDRATION THERAPY.

Although, in general, the standard WHO oral rehydration solution (ORS) is adequate,

lower osmolality oral rehydration fluids can be more effective in reducing stool

output. Compared with standard ORS, lower sodium and glucose ORS (containing 75

mEq of sodium and 75 mmol of glucose per liter, with total osmolarity of 245 mOsm

per liter) reduces stool output, vomiting, and the need for intravenous fluids without

substantially increasing the risk of hyponatremia.

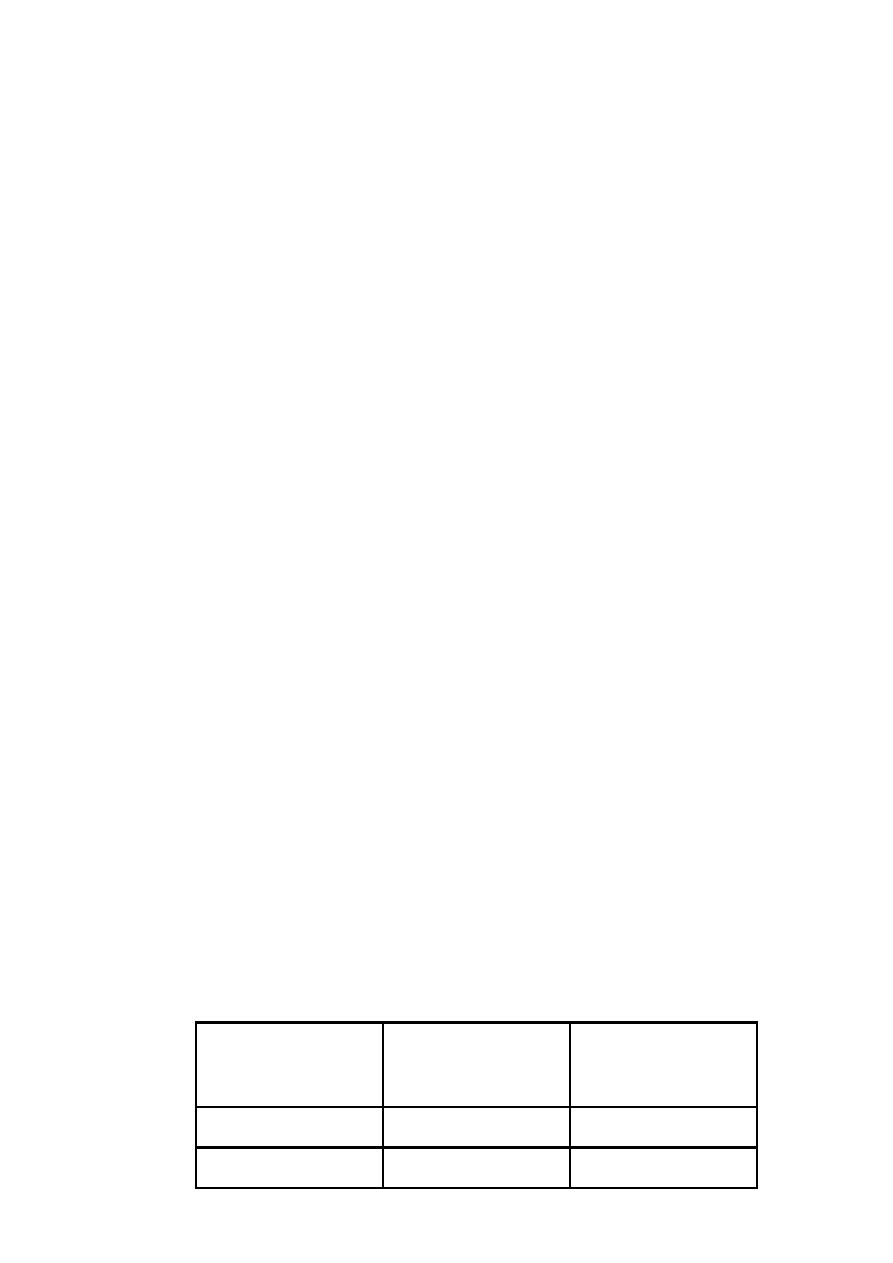

Composition of oral rehydration solution:

Reduced osmolarity ORS

mmol/l

Standard ORS solution

mEq or mmol/l

Minerals

75

111

Glucose

75

90

Sodium

65

80

chloride

20

20

Potassium

10

10

Citrate

245

311

osmolartiy

Cereal-based oral rehydration fluids can also be advantageous in malnourished

children and can be prepared at home. Home remedies including decarbonated soda

beverages, fruit juices, and tea are not suitable for rehydration or maintenance therapy

as they have inappropriately high osmolalities and low sodium concentrations. Oral

rehydration should be given to infants and children slowly, especially if they have

emesis. It can be given initially by a dropper, teaspoon, or syringe, beginning with as

little as 5 mL at a time. The volume is increased as tolerated.

Oral rehydration can also be given by a nasogastric tube if needed; this is not the usual

route. Limitations to oral rehydration therapy include shock, an ileus, intussusception,

carbohydrate intolerance (rare), severe emesis, and high stool output (>10 mL/kg/hr).

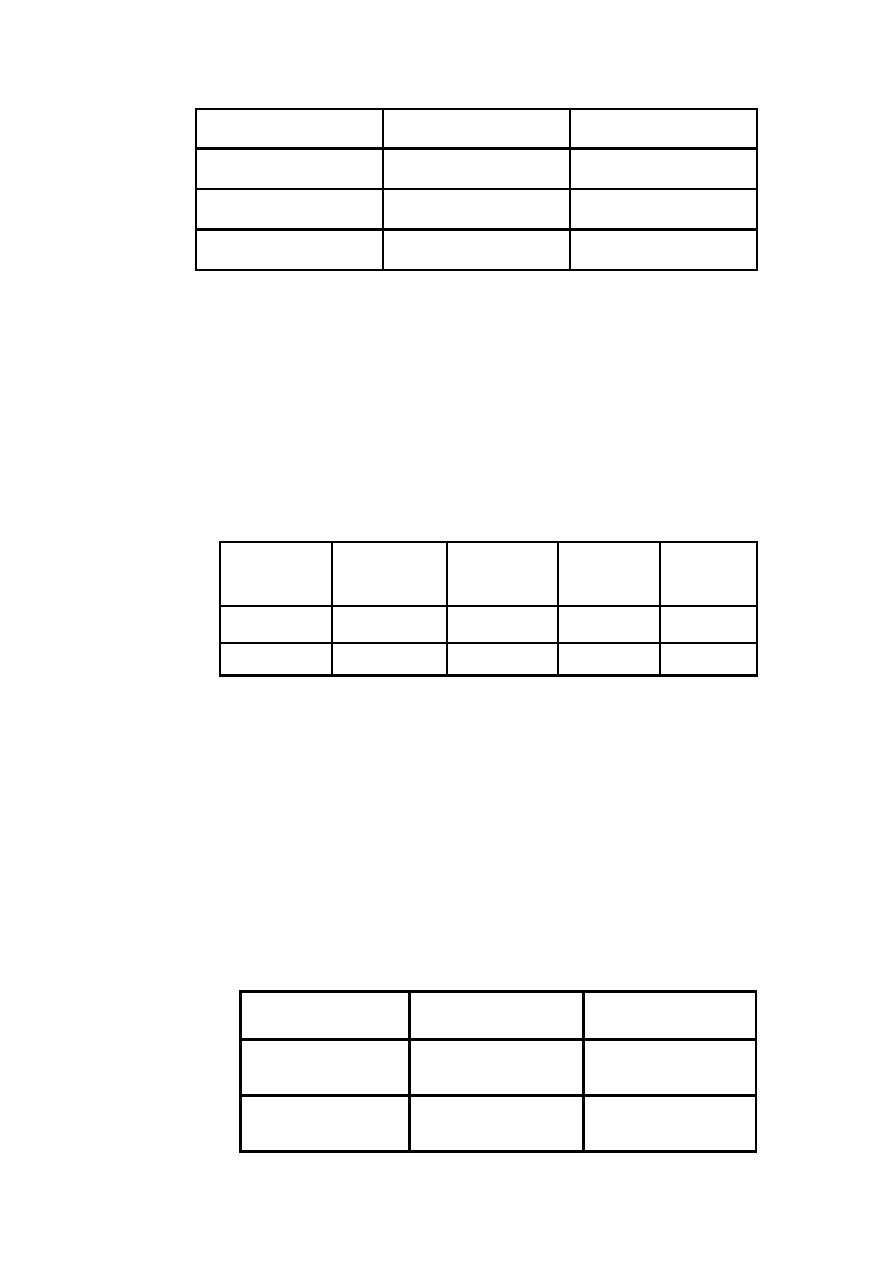

Diarrhea treatment plan B:

Treat some dehydration with ORS:

determine amount of ORS to give during first 4 hours.

2 years up

to

5 years

12 months

up to 2 years

4 months up

to 12 months

Up to 4

months

*

Age

12-19 kg

10-<12 kg

6-<10 kg

<6 kg

Weight

900-1400

700-900

400-700

200-400

In ml

* use the child's age only when do not know the weight. The approximate amount

of ORS required (in ml) can also be calculated by multiplying the child’s weight (in

kg) by 75

- if the child wants more ORS than shown, give more.

show the mother how to give ORS solution.

■ after 4 hours:

- reassess the child and classify the child for dehydration.

- select the appropriate plan to continue treatment.

-give zinc supplement

Diarrhea treatment plan C:

Treat sever dehydration quickly

start IV fluid immediately. If the child can drink, give ORS by mouth while the drip is

set up. Give 100 ml/kg Ringer's lactate solution (or, if not available, normal saline),

divided as follows:

Then give 70 ml/kg

in:

First give 30 ml/kg

in:

Age

5 hours

1 hour*

Infants (under 12

months)

2 1/2 hours

30 minutes*

Children (12 months

up to 5 years)

* repeat once if radial pulse is still very week or not detectable.

also give ORS (about 5 ml/kg/hour) as soon as the child can drink: usually after 3-4 hours

(infants) or 1-2 hours (children).

if IV fluid is not available, start rehydration by tube (or mouth) with ORS solution: give

20 ml/kg/hour for 6 hours (total of 120 ml/kg).

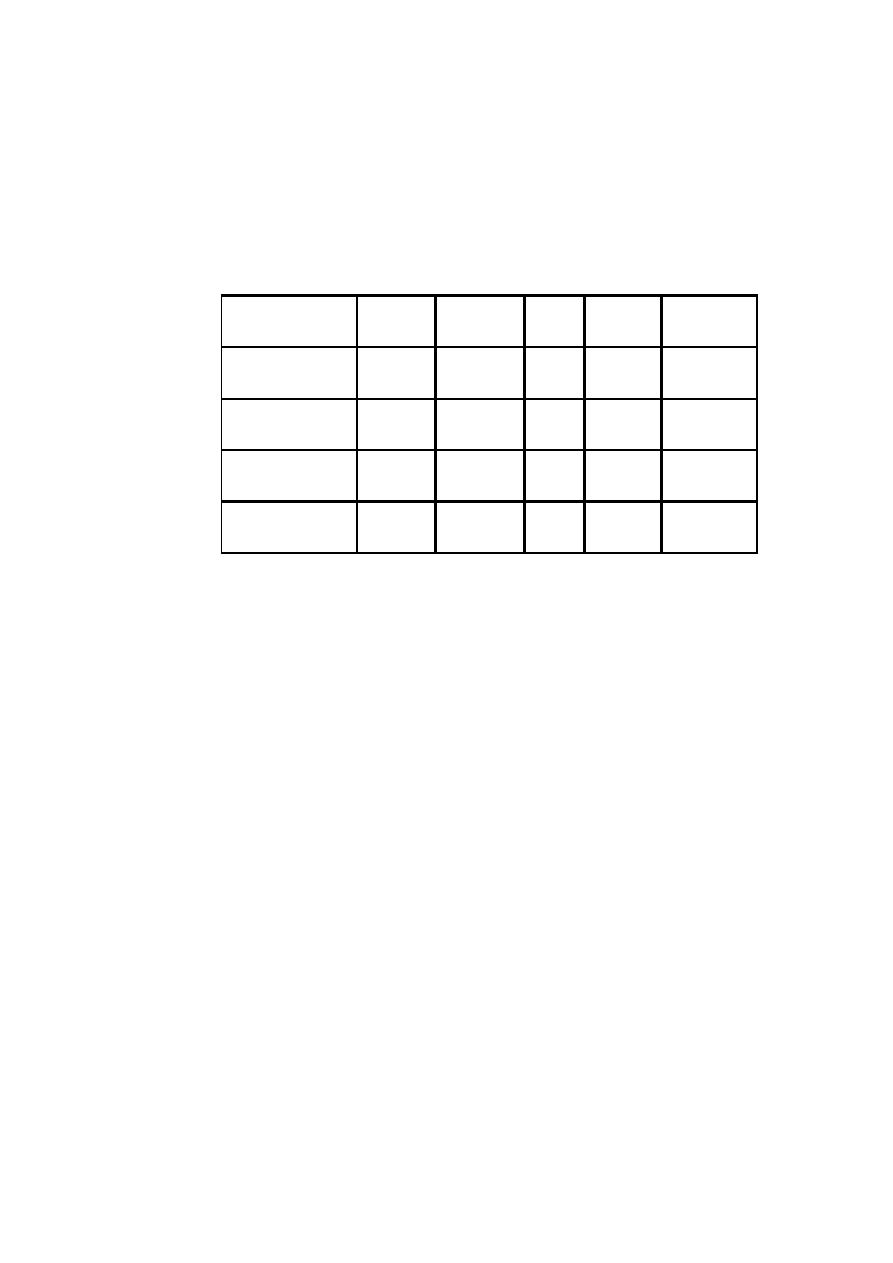

Types of fluids used intravenously:

In designing fluid management, it is important to know the component of the commonly

available solution.

lactate

Ca++

K+

Cl-

س

Na+

fluid

-

-

-

154

154

Normal saline

0.9 NaCl

-

-

-

77

77

Normal saline

0.45 NaCl

-

-

-

38.5

38.5

Normal saline

0.225 NaCl

28

3

4

109

130

Ringer lactate

The normal plasma osmolarity is 285-295 mosm/kg, infusing an intravenous solution

peripherally with a much lower osmolarity cause water to move into red blood cell

causing hemolysis, thus, intravenous fluids are generally designed to have an osmolarity

that is either close to 285 or moderately higher that is not cause problem, thus 1/4 N.S.

(osmolarity 77) should not be administered peripherally, but D5 1/4 N. S. (osmolarity

=355) or D5 1/2 N. S.+ 20 meq/l kcl (osmolarity 472) can be administered. The prefered

fluid for correction of dehydration is Ringer lactate and normal saline.

ADDITIONAL THERAPIES.

The use of probiotic nonpathogenic bacteria for prevention and therapy of diarrhea

has been successful in developing countries. There are a variety of organisms

(Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) that have a good safety record; therapy has not been

standardized and the most effective (and safe) organism has not been identified.

Antimotility agents (loperamide) are contraindicated in children with dysentery and

probably have no role in the management of acute watery diarrhea in otherwise

healthy children. Similarly, antiemetic agents such as the phenothiazines are of little

value and are associated with potentially serious side effects (lethargy, dystonia,

malignant hyperpyrexia). Nonetheless, ondansetron is an effective and less toxic

antiemetic agent. Because persistent vomiting may limit oral rehydration therapy, a

single sublingual dose of an oral dissolvable tablet of ondansetron (2 mg children 8–

15 kg; 4 mg children <15–30 kg; 8 mg children >30 kg) may be given. However,

most children do not require specific antiemetic therapy; careful oral rehydration

therapy is usually sufficient

Racecadotril, an enkephalinse inhibitor, has been shown to reduce stool output in

patients with diarrhea. Experience with this drug in children is limited, and for the

average child with acute diarrhea it may be unnecessary.

ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY.

Timely antibiotic therapy in select cases of diarrhea may reduce the duration and

severity of diarrhea and prevent complications. While these agents are important to

use in specific cases, their widespread and indiscriminate use leads to the

development of antimicrobial resistance. Nitazoxanide, an anti-infective agent, has

been effective in the treatment of a wide variety of pathogens including

Cryptosporidum parvum, Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, Blastocystis

hominis, C. difficile, and rotavirus

•

Dysentery

o

Requires antibiotic therapy

o

o

. Shigellae responds to cotrimoxazole

OR

o

Nalidixic acid 55 mg/kg/day in 4 doses x 5 days.

o

. Acute Amoebiasis:

o

Metronidazole -30 mg./kg/ day 3 doses x 5-10 days.

•

Cholera:-

Antibiotics used are:

o

Doxycycline- 6 mg/kg/day a single dose x 3 days or

o

. Tetracycline - 50 mg/kg/day 4 doses x 3 days or

o

. Erythromycin -30 mg/kg/day 3 doses x 3 days.

o

Note : doxycycline and tetracycline note used for children under 8 y. old

PREVENTION

In many developed countries, diarrhea due to pathogens such as Clostridum

botulinum, E. coli 0157 : H7, Salmonella, Shigella, V. cholerae, Cryptosporidium, and

Cyclospora is a notifiable disease and, thus, contact tracing and source identification

is important in preventing outbreaks.

PROMOTION OF EXCLUSIVE BREAST-FEEDING.

IMPROVED COMPLEMENTARY FEEDING PRACTICES.

There is a strong inverse association between appropriate, safe complementary

feeding and mortality in children age 6–11 mo; malnutrition is an independent risk for

the frequency and severity of diarrheal illness. Complementary foods should be

introduced at 6 mo of age while breast-feeding should continue for up to 1 yr (longer

period for developing countries). Complementary foods in developing countries are

generally poor in quality and frequently heavily contaminated, thus predisposing to

diarrhea. Contamination of complementary foods can be potentially reduced through

caregivers' education and improving home food storage. Vitamin A supplementation

reduces childhood mortality by 34%; improved vitamin A status reduces the

frequency of severe diarrhea.

ROTAVIRUS IMMUNIZATION.

Most infants acquire rotavirus diarrhea early in life; an effective rotavirus vaccine

would have a major effect on reducing diarrhea mortality in developing countries.

Rota virus vaccination:

Rota shield vaccine -1999 was licensed in America

. Withdrawn because of its association with intussusception

. Two new oral, live attenuated rotavirus vaccines were licensed in 2006 with very good

safety and efficacy

. The first dose administered between ages 6-10 weeks .

. subsequent doses at intervals 4-10 weeks.

. Vaccination should not be initiated before 6weeks and after 12 weeks of age.

. All doses should be administered before 32 weeks

Other vaccines that could potentially reduce the burden of severe diarrhea and

mortality in young children are vaccines against Shigella and ETEC

IMPROVED WATER AND SANITARY FACILITIES AND PROMOTION OF

PERSONAL AND DOMESTIC HYGIENE.

Much of the reduction in diarrhea prevalence in the developed world is the result of

improvement in standards of hygiene, sanitation, and water supply. In addition,

routine handwashing with plain soap in the home can reduce the incidence of diarrhea

in all environments.

IMPROVED CASE MANAGEMENT OF DIARRHEA.

Improved management of diarrhea through prompt identification and appropriate

therapy significantly reduces diarrhea duration, its nutritional penalty, and risk of

death in childhood. Improved management of acute diarrhea is a key factor in

reducing the burden of prolonged episodes and persistent diarrhea. The

WHO/UNICEF recommendations to use low osmolality ORS and zinc

supplementation for the management of diarrhea, coupled with selective and

appropriate use of antibiotics, have the potential to reduce the number of diarrheal

deaths among children.