Dr.Mushtaq Talib Hussein

F.I.B.M.S(ortho.) C.A.B.O(ortho.)

SUPRACONDYLAR FRACTURES

These are among the commonest fractures in children. The distal fragment may be

displaced either posteriorly (95%) or rare anteriorly.

Mechanism of injury

Usually due to a fall on the outstretched hand, the distal fragment is pushed backwards

and (because the forearm is usually in pronation) twisted inwards.

Anterior displacement is rare; it is thought to be due to direct violence (e.g. a fall on the

point of the elbow) with the joint in flexion.

Classification

Type I is an undisplaced fracture.

Type II is an angulated fracture with the posterior cortex still in continuity.

Type III is a completely displaced fracture (although the posterior periosteum is usually

still preserved, which will assist surgical reduction).

Type I Type II Type III

Clinical features

Following a fall, the child is in pain and the elbow is swollen; with a posteriorly

displaced fracture the S-deformity of the elbow is usually obvious and the bony

landmarks are abnormal. It is essential to feel the pulse and check the capillary return;

passive extension of the flexor muscles should be pain-free. The wrist and the hand

should be examined for evidence of nerve injury.

X-ray

Ap , lat. Views, fat pad sign(a triangular lucency in front of the distal humerus, due to the

fat pad being pushed forwards by a haematoma.) in case of undisplaced type.

On a normal lateral x-ray, a line drawn along the anterior cortex of the humerus should

cross the middle of the capitulum. If the line is anterior to the capitulum then a Type II

fracture is suspected.

Treatment

If there is even a suspicion of a fracture, the elbow is gently splinted in 30 degrees of

flexion to prevent movement and possible neurovascular injury during the x-ray

examination.

TYPE I: UNDISPLACED FRACTURE

The elbow is immobilized at 90 degrees and neutral rotation in a light-weight splint or

cast and the arm is supported by a sling. It is essential to obtain an x-ray5–7 days later to

check that there has been no displacement. The splint is retained for 3 weeks and

supervised movement is then allowed.

TYPE II: POSTERIORLY ANGULATED FRACTURE

The same regime above, if MUA failed to reduce the fracture accurately, the surgery is

the best treatment in which we use closed reduction fluoroscopy with percutaneous k-

wire fixation.

TYPES III: ANGULATED AND MALROTATED

These are usually associated with severe swelling, are difficult to reduce and are often

unstable; moreover, there is a considerable risk of neurovascular injury or circulatory

compromise due to swelling. The fracture should be reduced under general anaesthesia

as soon as possible, by the method described above, and then held with percutaneous

crossed K-wires; this obviates the necessity to hold the elbow acutely flexed.

OPEN REDUCTION

This is sometimes necessary for (1) a fracture which simply cannot be reduced closed;

(2) an open fracture; or (3) a fracture associated with vascular damage.

Complications

EARLY

Vascular injury The great danger of supracondylar fracture is injury to the brachial

artery, More commonly the injury is complicated by forearm oedema and a mounting

compartment syndrome which leads to necrosis of the muscle and nerves without

causing peripheral gangrene.

Nerve injury The radial nerve, median nerve(particularly the anterior interosseous

branch) or the ulnar nerve may be injured.

LATE

Malunion Malunion is common. However, backward or sideways shifts are gradually

smoothed out by modelling during growth and they seldom give rise to visible deformity

of the elbow.

Uncorrected sideways tilt (angulation) and rotation are much more important and may

lead to varus(gunstock deformity) (or rarely valgus) deformity of the elbow; this is

permanent and will not improve with growth

Elbow stiffness and myositis ossifficans Stiffness is an ever-present risk with elbow

injuries. Extension in particular may take months to return.

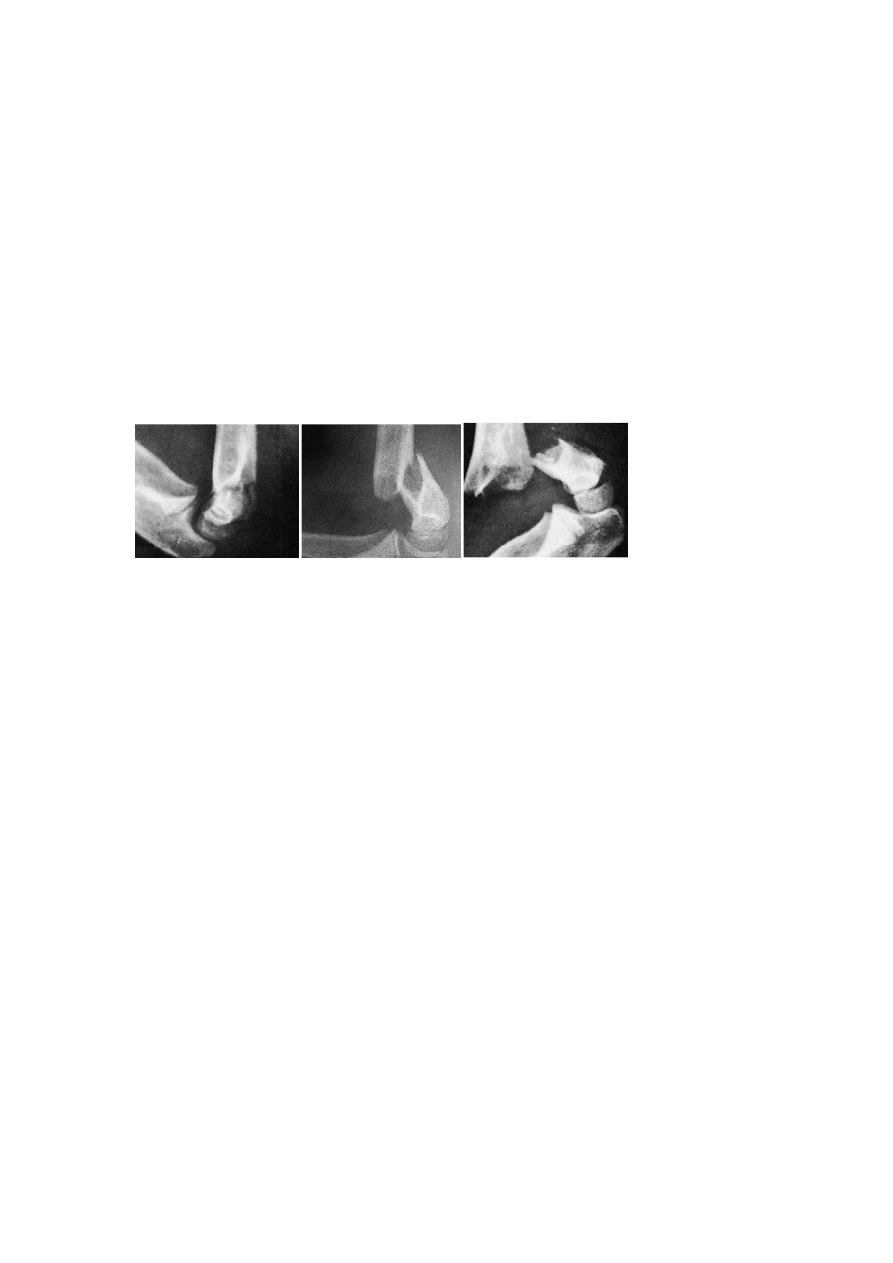

SUBLUXATION OF THE RADIAL HEAD(‘PULLED ELBOW’)

It is sometimes called subluxation of the radial head; more accurately, it is a subluxation

of the orbicular ligament which slips up over the head of the radius into the

radiocapitellar joint.

A child aged 2 or 3 years is brought with a painful, dangling arm: there is usually a

history of the child being jerked by the arm and crying out in pain. The forearm is held in

pronation and extension, and any attempt to supinate it is resisted. There are no x-ray

changes. A dramatic cure is achieved by forcefully supinating and then flexing the elbow;

the ligament slips back with a snap.

FRACTURES OF THE RADIUS AND ULNA

Mechanism of injury and pathology

Fractures of the shafts of both forearm bones occur quite commonly. A twisting force

(usually a fall on the hand) produces a spiral fracture with the bones broken at different

levels. An angulating force causes a transverse fracture of both bones at the same level.

A direct blow causes a transverse fracture of just one bone, usually the ulna.

Clinical features

The fracture is usually quite obvious, but the pulse must be felt and the hand examined

for circulatory or neural deficit. Repeated examination is necessary in order to detect an

impending compartment syndrome.

X-RAY

Both bones are broken, either transversely and at the same level or obliquely with the

radial fracture usually at a higher level. In children, the fracture is often incomplete

(greenstick) and only angulated. In adults, displacement may occur in any direction –

shift, overlap, tilt or twist. In low-energy injuries, the fracture tends to be transverse or

oblique; in high-energy injuries it is comminuted or segmental.

Treatment

CHILDREN

In children, closed treatment is usually successful because the tough periosteum tends

to guide and then control the reduction. The fragments are held in a well-moulded full-

length cast, from axilla to metacarpal shafts (to control rotation). with the elbow at 90

degrees.

The position is checked by x-ray after a week and, if it is satisfactory, splintage is

retained until both fractures are united (usually 6–8 weeks).

if the fracture cannot be

reduced or if the fragments are unstable. Fixation with intramedullary rods is preferred

,alternatively, a plate or K-wire fixation can be used.

Childhood fractures usually remodel well, but not if there is any rotational deformity or

an angular deformity of more than 15 degrees.

ADULTS

Unless the fragments are in close apposition, reduction is difficult and re-displacement

in the cast almost invariable. So predictable is this outcome that most surgeons opt for

open reduction and internal fixation from the outset.

Complications

EARLY

Nerve injury Nerve injuries are rarely caused by the fracture, but they may be caused by

the surgeon! Exposure of the radius in its proximal third risks damage to the posterior

interosseous nerve.

Vascular injury Injury to the radial or ulnar artery seldom presents any problem, as the

collateral circulation is excellent.

Compartment syndrome Fractures (and operations) of the forearm bones are always

associated with swelling of the soft tissues, with the attendant risk of a compartment

syndrome.

LATE

Delayed union and non-union Most fractures of the radius and ulna heal within 8–12

weeks; high energy fractures and open fractures are less likely to unite.

Malunion With closed reduction there is always a risk of malunion, resulting in

angulation or rotational deformity of the forearm, cross-union of the fragments, or

shortening of one of the bones and disruption of the distal radio-ulnar joint.

Complications of plate removal Removal of plates and screws is often regarded as a

fairly innocuous procedure.

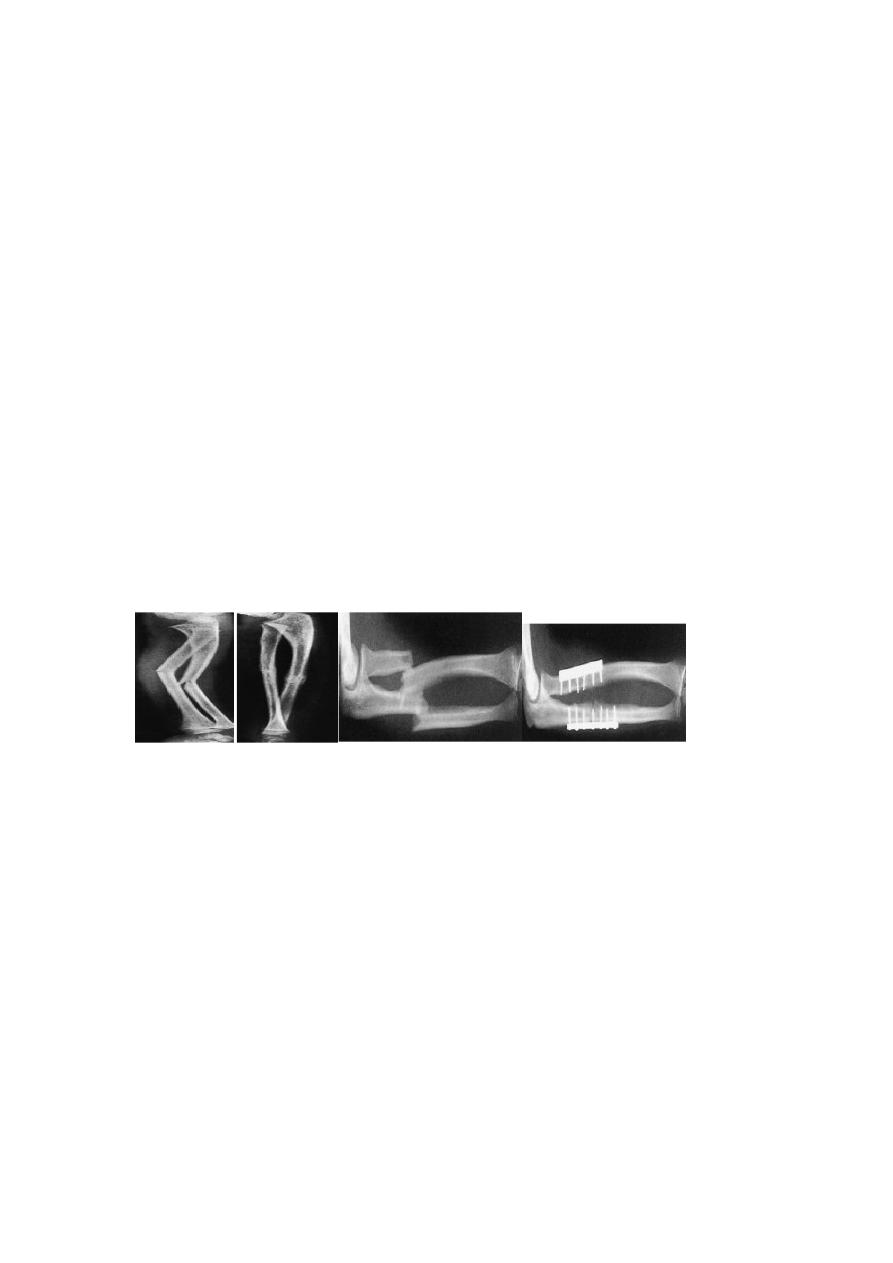

MONTEGGIA FRACTUREDISLOCATION OF THE ULNA

The injury described by Monteggia in the early nineteenthth century (without benefit of

x-rays!) was a fracture of the shaft of the ulna associated with dislocation of the

proximal radio-ulnar joint; the radiocapitellar joint is inevitably dislocated or

subluxated as well. More recently the definition has been extended to embrace almost

any fracture of the ulna associated with dislocation of the radio-capitellar joint,

including trans-olecranon fractures in which the proximal radioulnar joint remains

intact.

Mechanism of injury

Usually the cause is a fall on the hand; if at the moment of impact the body is twisting, its

momentum may forcibly pronate the forearm. The radial head usually dislocates

forwards and the upper third of the ulna fractures and bows forwards.

Clinical features

The ulnar deformity is usually obvious but the dislocated head of radius is masked by

swelling. A useful clue is pain and tenderness on the lateral side of the elbow. The wrist

and hand should be examined for signs of injury to the radial nerve.

X-ray With isolated fractures of the ulna, it is essential to obtain a true anteroposterior

and true lateral view of the elbow. In the usual case, the head of the radius(which

normally points directly to the capitulum) is dislocated forwards, and there is a fracture

of the upper third of the ulna with forward bowing.

Treatment

The key to successful treatment is to restore the length of the fractured ulna;

only then can the dislocated joint be fully reduced and remain stable. In adults, this

means an surgery(open reduction and internal fixation of ulnar fracture)

In a child, closed reduction and plaster is usually satisfactory.

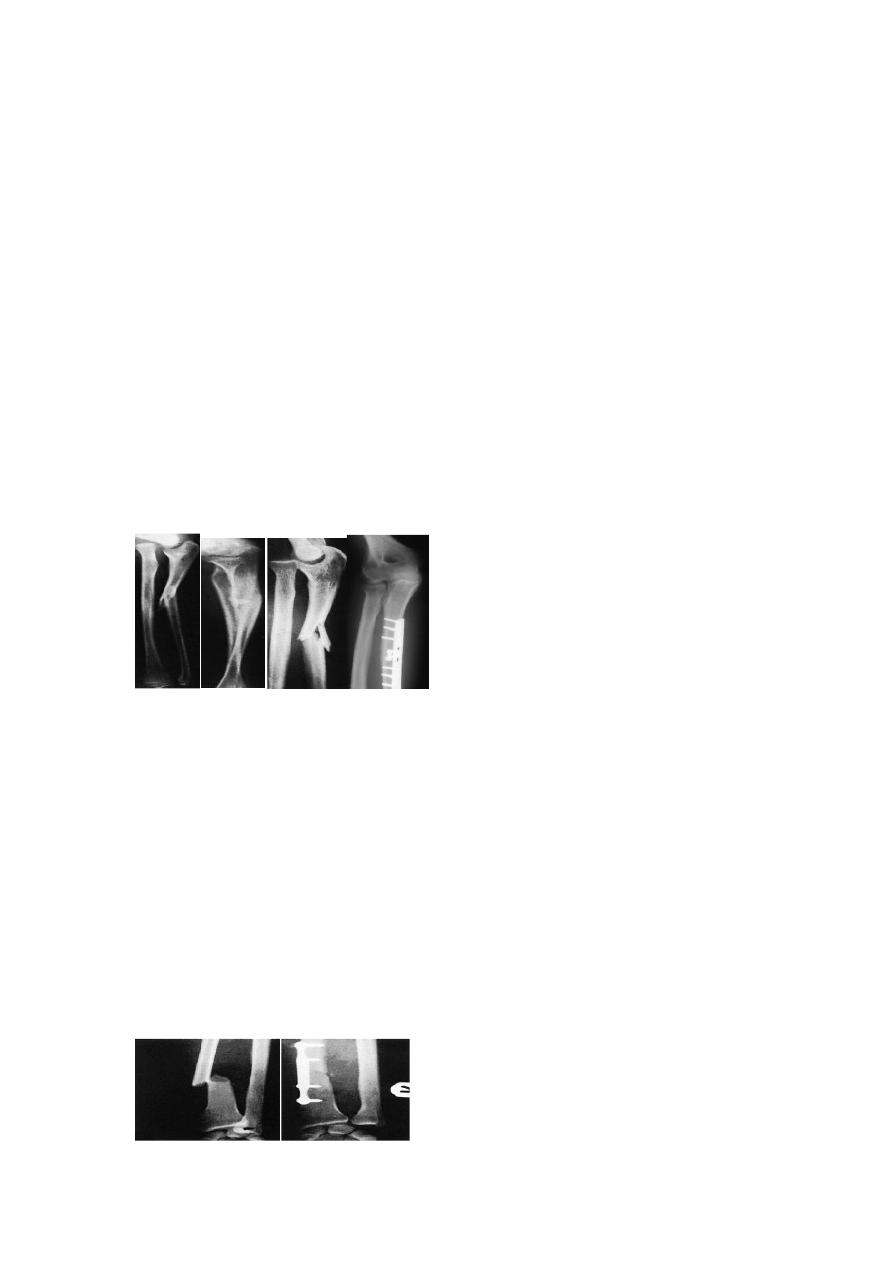

GALEAZZI FRACTURE-DISLOCATION OF THE RADIUS

Mechanism of injury

This injury was first described in 1934 by Galeazzi. The usual cause is a fall on the hand;

probably with a superimposed rotation force. The radius fractures in its lower third and

the inferior radio-ulnar joint subluxates or dislocates.

Clinical features

The Galeazzi fracture is much more common than the Monteggia. Prominence or

tenderness over the lower end of the ulna is the striking feature. It may be possible to

demonstrate the instability of the radio-ulnar joint by ‘ballotting’ the distal end of the

ulna (the ‘piano-key sign’) or by rotating the wrist. It is important also to test for an

ulnar nerve lesion, which may occur.

X-ray A transverse or short oblique fracture is seen in the lower third of the radius, with

angulation or overlap. The distal radio-ulnar joint is subluxated or dislocated.

Treatment

As with the Monteggia fracture, the important step is to restore the length of the

fractured bone. In children, closed reduction is often successful; in adults, reduction is

best achieved by open operation and compression plating of the radius. An x-ray is

taken to ensure that the distal radio-ulnar joint is reduced.