CHRONIC INFLAMMATION

Chronic inflammation is inflammation of prolonged

duration (weeks to months to years) in which active

inflammation, tissue injury, and healing proceed

simultaneously

.

In contrast to acute inflammation, which is distinguished

by vascular changes, edema, and a predominantly

neutrophilic infiltrate, chronic inflammation is

characterized by

:

1.

Infiltration with mononuclear cells, including

macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells

2.

Tissue destruction, largely induced by the products of

the inflammatory cells

3.

Repair, involving new vessel proliferation (angiogenesis)

and

fibrosis

acute inflammation may progress to chronic

inflammation. This transition occurs when the

acute response cannot be resolved, either

because of the persistence of the injurious

agent or because of interference with the

normal process of healing. For example, a

peptic ulcer of the duodenum initially shows

acute inflammation followed by the beginning

stages of resolution

.

Alternatively, some forms of injury (e.g., viral

infections) engender a response that involves

chronic inflammation from the onset

.

Causes of chronic inflammation

:

1. Persistent infections

:

by microbes that are difficult to eradicate. These include

mycobacteria ,

Treponema pallidum, (

causative

organism of syphilis), and certain viruses and fungi, all

of which tend to establish persistent infections and elicit

a

delayed-type hypersensitivity

. In fact, most viral

infections elicit chronic inflammatory reactions

dominated by lymphocytes and macrophages

2. hypersensitivity disease

diseases that are caused by excessive and inappropriate

activation of the immune system are increasingly

recognized as being important health problems)

under certain conditions, immune reactions develop

against the individual's own tissues, leading to

autoimmune diseases

. In these diseases, autoantigens

evoke a self-immune reaction that results in chronic

tissue damage and inflammation. Inflammation

secondary to autoimmunity plays an important role in

several common and debilitating chronic diseases,

such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel

disease. Immune responses against common

environmental substances are the cause of

allergic

diseases ,

such as bronchial asthma.

3. Prolonged exposure to potentially toxic agents .

:

either exogenous materials such as inhaled

particulate silica, which can induce

silicosis

or

endogenous agents such as chronically elevated

plasma lipid components, which may contribute to

atherosclerosis

)

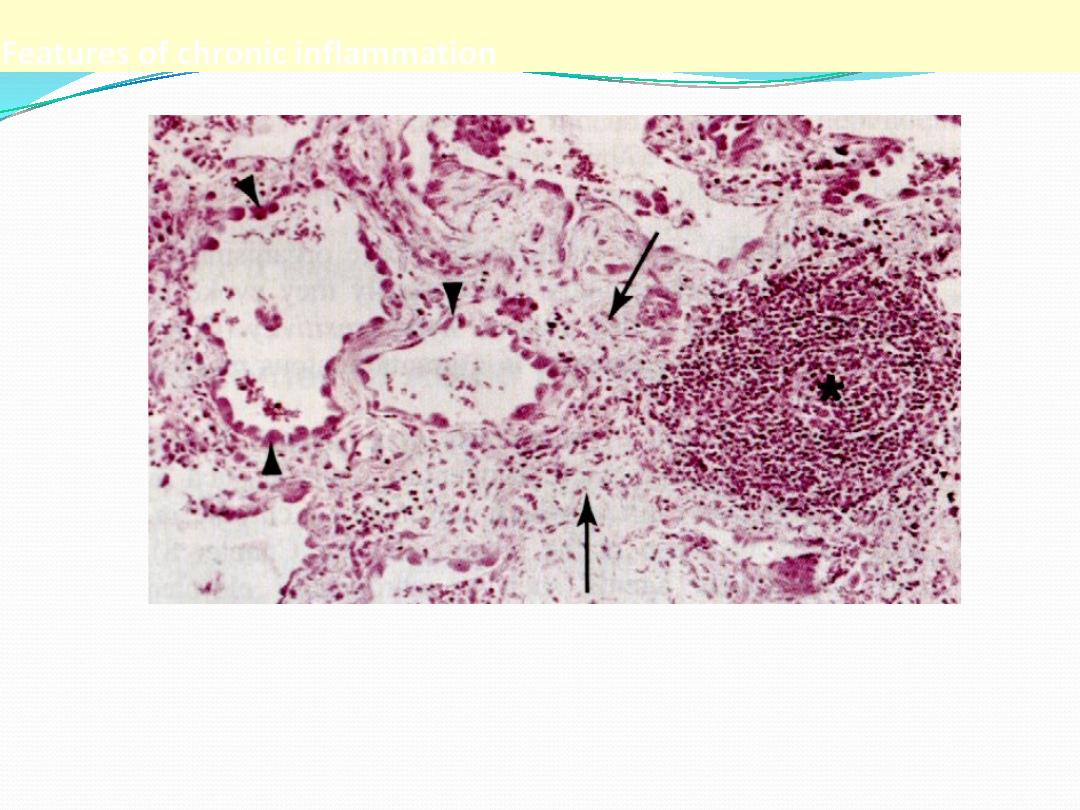

Features of chronic inflammation

The three characteristic features of chronic inflammation (in the lung)

1. Chronic inflammatory cells infiltration* 2. destruction of the normal tissue

(normal alveoli are replaced by spaces lined by cuboidal cells (arrow heads)

3. Replacement by fibrosis (arrows)

Chronic Inflammatory Cells and Mediators

chronic inflammation results from complex interactions between the cells that are

recruited to the site of inflammation and are activated at this site.

1. Macrophages:

the dominant cells of chronic inflammation, are tissue cells derived from

circulating blood monocytes after their emigration from the bloodstream.

Macrophages are normally diffusely scattered in most connective tissues, and are

also found in organs such as the liver (where they are called Kupffer cells), spleen

and lymph nodes (called sinus histiocytes), central nervous system (microglial

cells), and lungs (alveolar macrophages). Together these cells comprise the so-called

mononuclear phagocyte system, also known by the older name of reticulo-

endothelial system

2. Lymphocytes :

are mobilized to the setting of any specific immune stimulus (i.e., infections) as well

as non-immune-mediated inflammation (e.g., due to infarction or tissue trauma).

Both T and B lymphocytes migrate into inflammatory sites using some of the same

adhesion molecule pairs and chemokines that recruit other leukocytes.

Lymphocytes and macrophages interact in a bidirectional way, and these

interactions play an important role in chronic inflammation. Macrophages display

antigens to T cells that stimulate them . Activated T lymphocytes, in turn, produce

cytokines, and one of these, IFN-γ, is a powerful activator of macrophages

The half-life of circulating monocytes is about 1 day; under the influence

of adhesion molecules and chemotactic factors, they begin to migrate to

a site of injury within 24 to 48 hours after the onset of acute

inflammation,. When monocytes reach the extravascular tissue, they

undergo transformation into larger macrophages, which have longer half-

lives and a greater capacity for phagocytosis than do blood monocytes.

Macrophages may also become activated

,

resulting in increased cell size,

increased content of lysosomal enzymes, more active metabolism, and

greater ability to kill ingested organisms. By light microscopy, activated

macrophages appear large, flat, and pink (in H&E stains); this

appearance may be similar to that of squamous epithelial cells, and cells

with such an appearance are therefore sometimes called epithelioid cells

.

Activation signals include bacterial endotoxin and other microbial

products, cytokines secreted by sensitized T lymphocytes (in particular

the cytokine IFN-γ), various mediators produced during acute

inflammation, and ECM proteins such as fibronectin. After activation,

macrophages secrete a wide variety of biologically active products that, if

unchecked, can result in the tissue injury and fibrosis that are

characteristic of chronic inflammation

) Fig. 2-21 .(These products

include

Acid and neutral proteases

.

Recall that the latter were also implicated as

mediators of tissue damage in acute inflammation. Other enzymes, such as

plasminogen activator

,

greatly amplify the generation of proinflammatory

substances

.

ROS and NO

AA metabolites.

Cytokines

such as IL-1 and TNF, as well as a variety of growth factors that

influence the proliferation of smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts and the

production of ECM

After the initiating stimulus is eliminated and the inflammatory reaction

abates, macrophages eventually die or wander off into lymphatics. In chronic

inflammatory sites, however, macrophage accumulation persists, and

macrophages can proliferate. Steady release of lymphocyte-derived

chemokines and other cytokines is an important mechanism by which

macrophages are recruited to or immobilized in inflammatory sites. IFN-γ can

also induce macrophages to fuse into large, multinucleated cells called giant

cells

3. Eosinophils

are characteristically found in inflammatory sites around parasitic

infections or as part of immune reactions mediated by IgE, typically

associated with allergies

.

Their recruitment is driven by adhesion molecules similar to those used by

neutrophils, and by specific chemokines (e.g., eotaxin) derived from

leukocytes or epithelial cells. Eosinophil granules contain major basic

protein, a highly charged cationic protein that is toxic to parasites but also

causes epithelial cell necrosis

.

4. Mast cells

are sentinel cells widely distributed in connective tissues throughout the

body, and they can participate in both acute and chronic inflammatory

responses. In atopic individuals (individuals prone to allergic reactions),

mast cells are "armed" with IgE antibody specific for certain

environmental antigens.

When these antigens are subsequently encountered, the IgE-coated mast

cells are triggered to release histamines and AA metabolites that elicit the

early vascular changes of acute inflammation. IgE-armed mast cells are

central players in allergic reactions, including anaphylactic shock.

Mast cells can also elaborate cytokines such as TNF and chemokines and

may play a beneficial role in some infections.

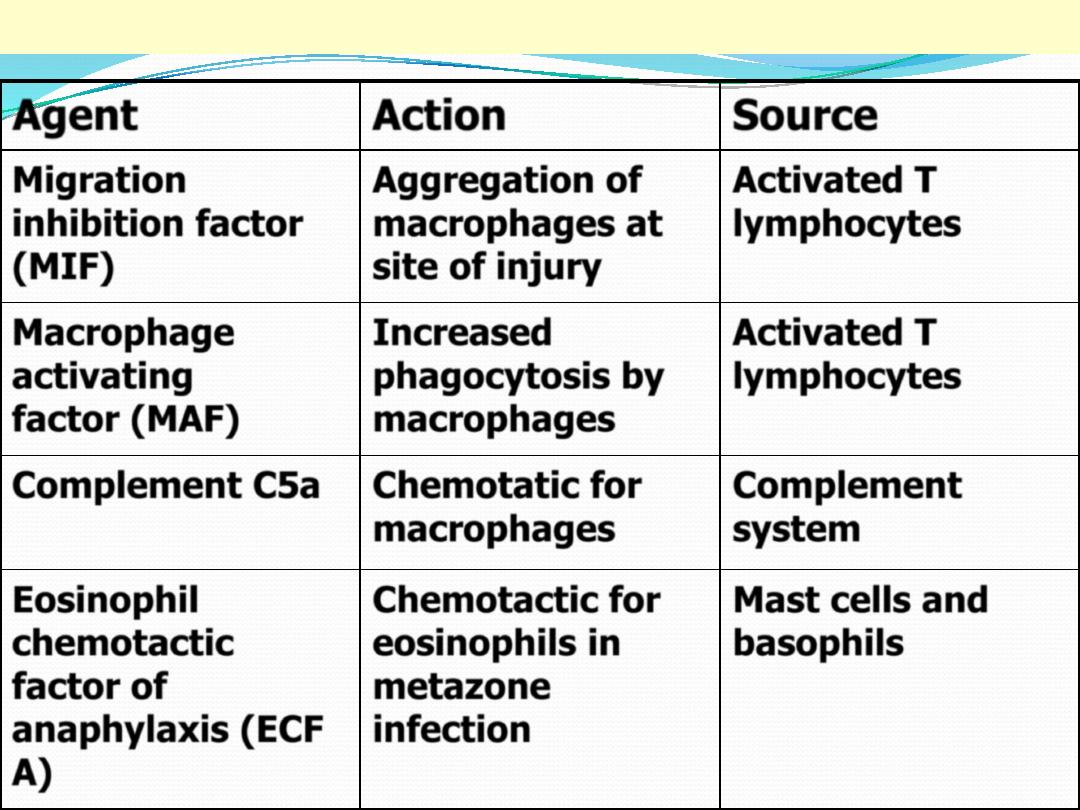

Mediators of chronic inflammation

Agent

Action

Source

Migration

inhibition factor

(MIF)

Aggregation of

macrophages at

site of injury

Activated T

lymphocytes

Macrophage

activating

factor (MAF)

Increased

phagocytosis by

macrophages

Activated T

lymphocytes

Complement C5a

Chemotatic for

macrophages

Complement

system

Eosinophil

chemotactic

factor of

anaphylaxis (ECF

A)

Chemotactic for

eosinophils in

metazone

infection

Mast cells and

basophils

Granulomatous inflammation

is a distinctive pattern of chronic inflammation

characterized by aggregates of activated macrophages

that assume an epithelioid appearance.

Granulomas are encountered in certain specific

pathologic states; consequently, recognition of the

granulomatous pattern is important because of the

limited number of conditions (some life-threatening)

that cause it

.

Granulomas can form in the setting of persistent T-cell

responses to certain microbes (such as Mycobacterium

tuberculosis, T. pallidum

,

or fungi), where T-cell-

derived cytokines are responsible for chronic

macrophage activation

.

Tuberculosis is the prototype of a granulomatous

disease caused by infection and should always be

excluded as the cause when granulomas are identified

.

Granulomas may also develop in response to

relatively inert foreign bodies (e.g., suture or

splinter), forming so-called foreign body

granulomas

.

The formation of a granuloma effectively "walls

off" the offending agent and is therefore a useful

defense mechanism.

However, granuloma formation does not always

lead to eradication of the causal agent, which is

frequently resistant to killing or degradation,

and granulomatous inflammation with

subsequent fibrosis may even be the major

cause of organ dysfunction in some diseases,

such as tuberculosis

.

Causes of granulomatous inflammation:

granulomatous inflammation is encountered in a number of

immunologically mediated infectious and non-infectious

conditions, these include:

1.

Tuberculosis

2.

Sarcoidosis

3.

Cat-scratch disease

4.

Lymphogranuloma inguinale

5.

Leprosy

6.

Brucelosis

7.

Syphilis

8.

Some fungal infection

9.

Reactions of irretant lipid

Recognition of granuloma in biopsy specimen is

important because it shorten the list of differetial

diagnosis .agranuloma is a focus of chronic

inflammation consist of aggregation of

macrophages that are transformed into epithelioid

cells surrounded by a collar of mononuclear

leukocytes principally lymphocytes and

occasionally plasma cells.older granulomas

develop an enclosing rim of fibroblasts and

connective tissue .frequently , epithelioid cells fuse

to form multinucleated giant cells in periphery or

some time in the center of the granuloma.they

have 20 or more small nuclei arranged either

peripherally (Langhans-type giant cell) or

haphazardlly ( foreign body

–type giant cell )

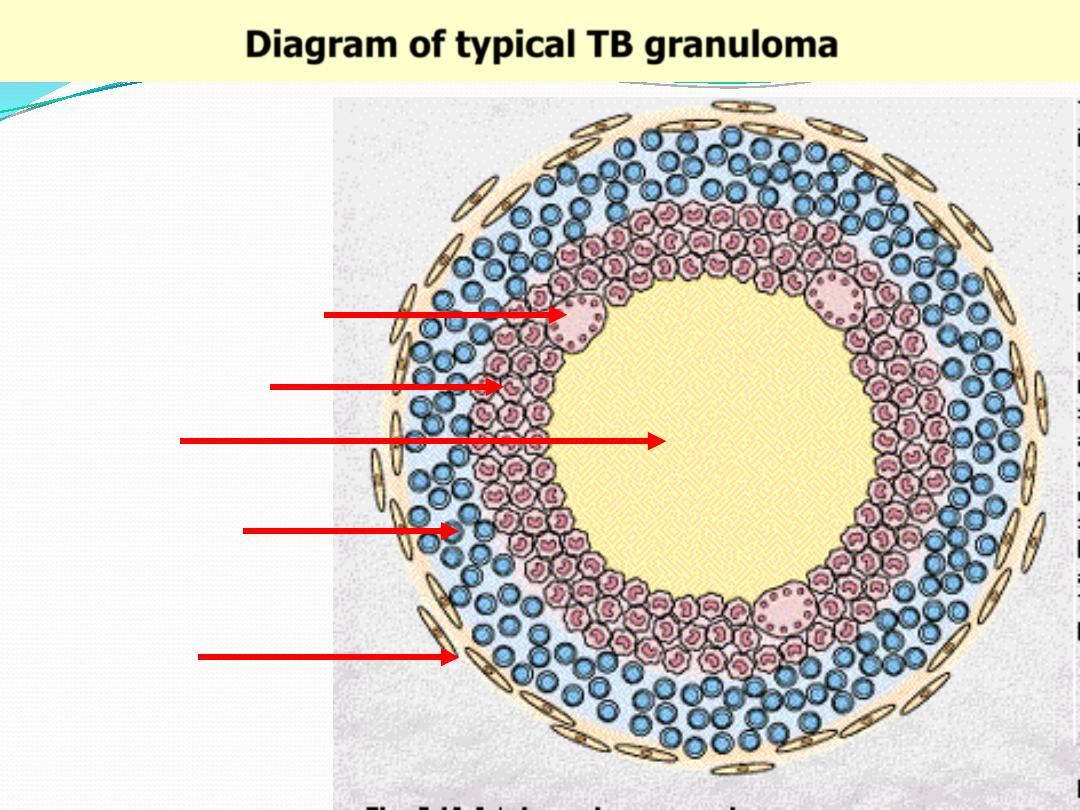

Diagram of typical TB granuloma

Caseation

Epithelioid cells

Multinucleated GC

Lymphocytes

Fibroblasts

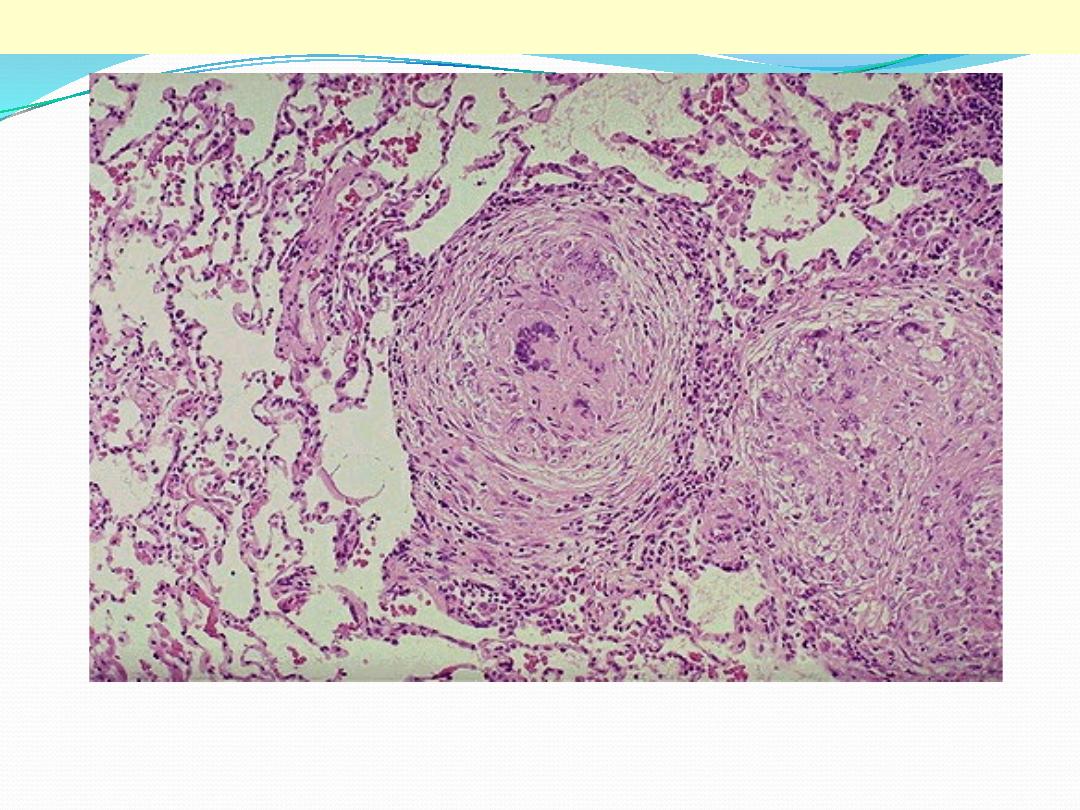

This is a low power view showing two, adjacent, well-defined, rounded granulomas . From this power

the presence of multinucleated giant cells is obvious (arrow).

TB granulomas lung

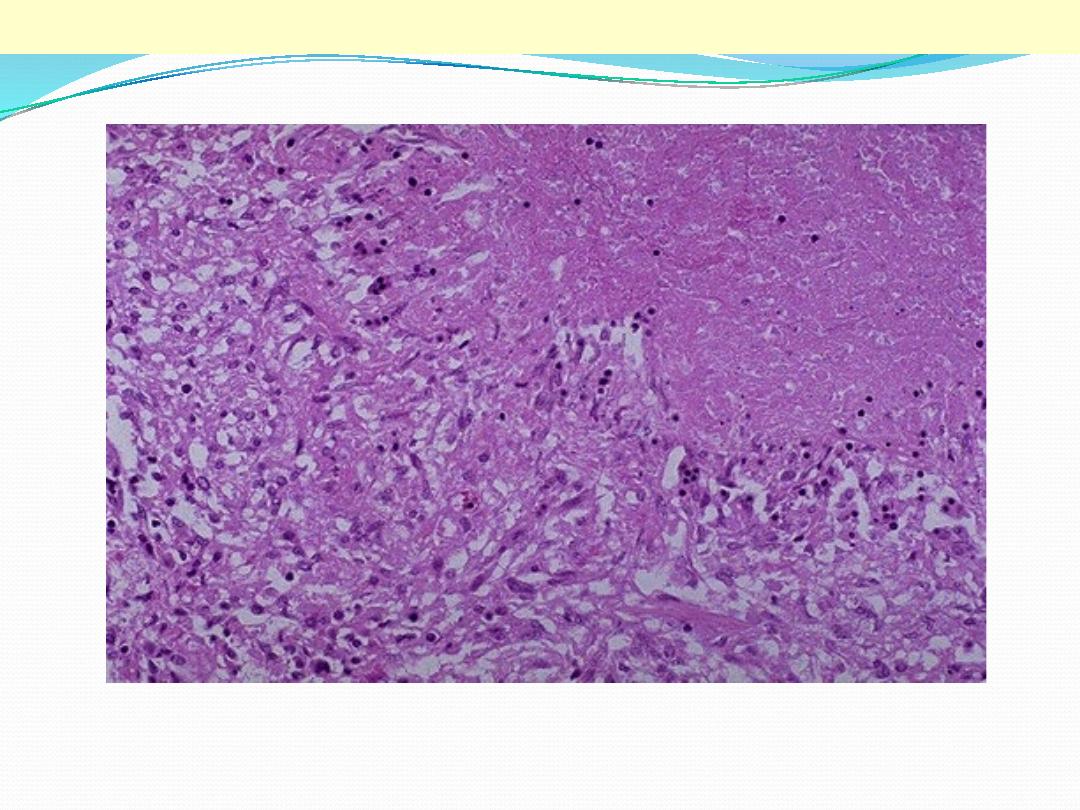

This is a high power view showing a portion of typical TB granuloma. Note the amorphous, pinkish

central caseation, which is surrounded by a rim of epithelioid cells.

TB granulomas

Epithelioid cells

Caseation

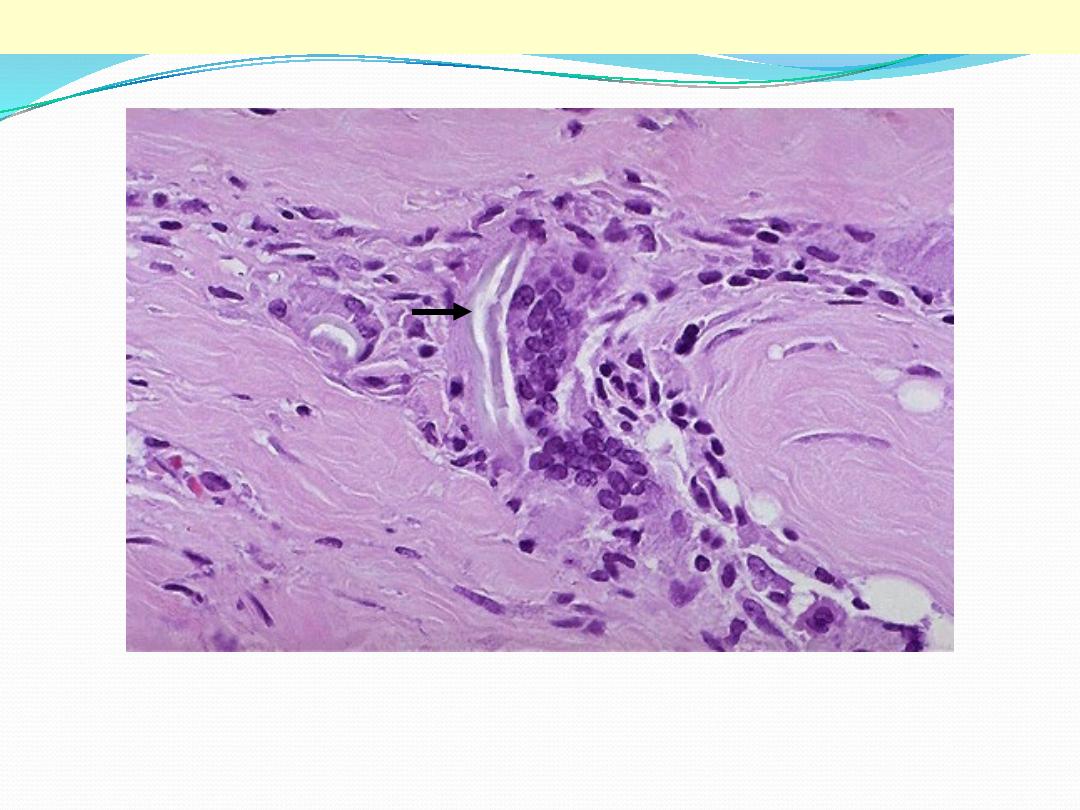

Two foreign body giant cells are seen, where there is a bluish strand of suture material (arrow) from a

previous operation

Foreign body giant cells in suture granuloma

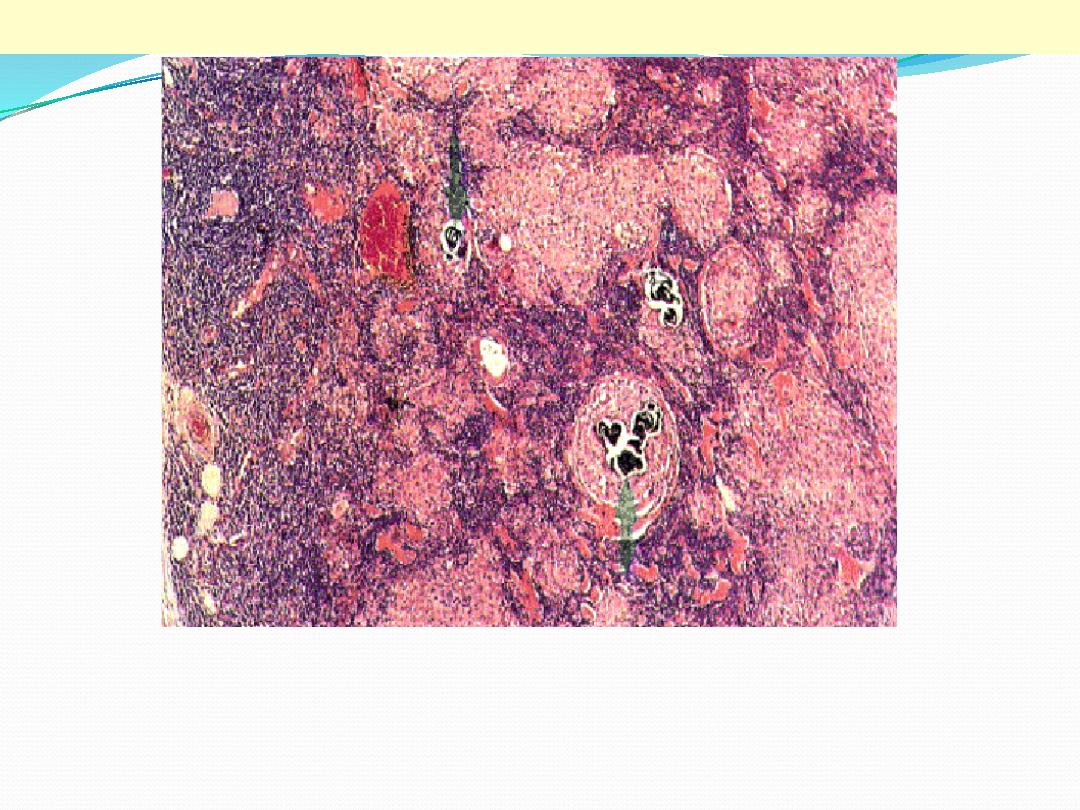

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous inflammatory disease which affects many tissues, including lymphoid

tissue. The capsule of the node is on the left. The normal architecture of the node has been largely

destroyed, with some blue-staining lymphoid tissue surviving beneath the capsule and between the

round sarcoid granulomas. The latter vary widely in size, from a few cells to very large collections

(right) several mm in diameter. They consist of epithelioid histiocytes. There is no caseation, but some

contain calcified laminated Schaumann bodies (arrows).

Sarcoidosis lymph node

SYSTEMIC EFFECTS OF INFLAMMATION

the systemic effects of inflammation, collectively called the acute-

phase reaction, or the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. The

cytokines TNF, IL-1, and IL-6 are the most important mediators of the

acute-phase reaction.

The acute-phase response consists of several clinical and pathologic

changes:

1. Fever :

is produced in response to substances called pyrogens that act by

stimulating prostaglandin (PG) synthesis in the vascular and

perivascular cells of the hypothalamus.

2. Acute-phase proteins:

which are plasma proteins, mostly synthesized in the liver, whose

concentrations may increase several 100-fold as part of the response to

inflammatory stimuli Three of the best-known of these proteins are C-

reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, and serum amyloid A (SAA) protein .

CRP and SAA, bind to microbial cell walls, and they may act as opsonins and fix complement,

thus promoting the elimination of the microbes. Fibrinogen binds to erythrocytes and

causes them to form stacks (rouleaux) that sediment more rapidly at unit gravity than do

individual erythrocytes

.

3.

Leukocytosis

is a common feature of inflammatory reactions, especially those induced by bacterial

infection. The leukocyte count usually climbs to 15,000 or 20,000 cells/μL, but sometimes it

may reach extraordinarily high levels, as high as 40,000 to 100,000 cells/μL. These extreme

elevations are referred to as leukemoid reactions because they are similar to the white cell

counts obtained in leukemia. The leukocytosis occurs initially because of accelerated

release of cells from the bone marrow postmitotic reserve pool (caused by cytokines,

including TNF and IL-1) and is therefore associated with a rise in the number of more

immature neutrophils in the blood (shift to the left). Prolonged infection also stimulates

production of colony-stimulating factors (CSFs), leading to increased bone marrow output

of leukocytes, which compensates for the loss of these cells in the inflammatory reaction.

Most bacterial infections induce an increase in the blood neutrophil count, called

neutrophilia. Viral infections, such as infectious mononucleosis, mumps, and German

measles, are associated with increased numbers of lymphocytes (lymphocytosis). Bronchial

asthma, hay fever, and parasite infestations all involve an increase in the absolute number

of eosinophils, creating an eosinophilia. Certain infections (typhoid fever and infections

caused by some viruses, rickettsiae, and certain protozoa) are paradoxically associated with

a decreased number of circulating white cells (leukopenia), likely because of cytokine-

induced sequestration of lymphocytes in lymph nodes.

4. Other manifestations of the acute-phase response include

increased heart rate and blood pressure; decreased sweating,

mainly because of redirection of blood flow from cutaneous to

deep vascular beds, to minimize heat loss through the skin; and

rigors (shivering), chills (perception of being cold as the

hypothalamus resets the body temperature), anorexia, and

malaise, probably because of the actions of cytokines on brain

cells. Chronic inflammation is associated with a wasting syndrome

called cachexia

,

which is mainly the result of TNF-mediated

appetite suppression and mobilization of fat stores

5. In severe bacterial infections (sepsis), the large amounts of organisms and

LPS in the blood or extravascular tissue stimulate the production of

enormous quantities of several cytokines, notably TNF, as well as IL-12 and

IL-1. As a result, circulating levels of these cytokines increase, and the

nature of the host response changes. High levels of TNF cause

disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), hypoglycemia, and

hypotensive shock. This clinical triad is described as septic shock.

Thank you