الدكتور

ضياء كاظم الوائليشهادة الاختصاص الدقيق في السكري والغدد الصماء

شهادة البورد (الدكتوراه) للامراض الباطنيه والقلبيه والصدريه

عضو الجمعيه الامريكيه للسكري والغدد الصماء

عضو الهيئة التدريسية في كلية الطب - جامعة ذ ي قار

L4 29 DEC 2020

Enteral feedingWhere swallowing or food ingestion is impaired but intestinal function remains intact, more invasive forms of assisted feeding may be necessary. Enteral tube feeding is usually the intervention of choice. In enteral feeding, nutrition is delivered to and absorbed by the functioning intestine. Delivery usually means bypassing the mouth and oesophagus (or sometimes the stomach and proximal small bowel) by means of a feeding tube (naso-enteral, gastrostomy or jejunostomy feeding). There are a number of theoretical advantages to enteral, as opposed to parenteral feeding, which have achieved almost mythical status.

These include:

• Preservation of intestinal mucosal architecture, gut associated lymphoid tissue, and hepatic and pulmonary immune function• Reduced levels of systemic inflammation and hyperglycaemia

• Interference with pathogenicity of gut micro-organisms.

• Fewer episodes of infection

• Reduced cost

• Earlier return to intestinal function

• Reduced length of hospital stay.

Route of access

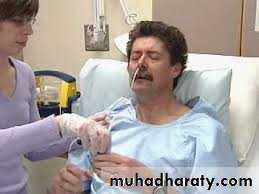

Nasogastric tube feeding (NG tube) This is simple, readily available, comparatively low-cost and most suitable for short-term feeding (up to 4 weeks). Insertion of a NG tube requires care and training, as potentially serious complications can arise. Patients with reduced conscious level may pull at tubes and displace them.

This can be minimised in the short term by the use of a nasal ‘bridle’ device, which fixes the tube around the nasal septum.

Although these devices are very effective, there is a risk of damage to the nasal septum (especially bleeding) if a patient persists in pulling forcibly on the tube.

Complications of nasogastric tube feeding

• Tube misplacement, e.g. tracheal or bronchial placement (rarely, intracranial placement)• Reflux of gastric contents and pulmonary aspiration

• Interrupted feeding or inadequate feed volumes

• Refeeding syndrome

Diarrhoea related to enteral feeding (Factors contributing to diarrhoea)

• Fibre-free feed may reduce short-chain fatty acid production in colon• Fat malabsorption

• Inappropriate osmotic load

• Pre-existing primary gut problem (e.g. lactose intolerance)

• Infection

Management

• Often responds well to a fibre-containing feed or a switch to an

alternative feed

• Simple anti diarrhoeal agents (e.g. loperamide) can be very effective

Gastrostomy feeding

Gastrostomy is a more invasive insertion technique with higher costs initially. It is most suitable for when longer-term feeding (more than 4 weeks) is required.

Gastrostomies are less liable to displacement than nasogastric tubes and the presence of the gastrostomy in the stomach allows for fewer feed interruptions, meaning that more of the prescribed feeds can be administered.

Tubes were placed at the time of open surgery until the 1980s, when an endoscopic, minimally invasive technique was developed.

A variety of techniques for radiological insertion have also been introduced subsequently.

Both endoscopic and radiological gastrostomy insertion involve inflating the stomach, thus apposing it to the anterior abdominal wall.The stomach is then punctured percutaneously and a suitable

tube placed.Tubes vary in design but each has an internal retainer device (plastic ‘bumper’ or balloon) that sits snugly against the gastric mucosa, and an external retainer that limits movement.

These retainers hold the gastric wall against the abdominal wall, effectively creating a controlled gastro-cutaneous fistula that matures over 2–4 weeks.

Radiological gastrostomy placement also utilizes percutaneous ‘stay sutures’, which provide further temporary anchorage and assist in placement.

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) placement.

A. Finger pressure on the anterior abdominal wall is noted by the endoscopist.B. Following insertion of a cannula through the anterior abdominal wall into the stomach, a guidewire is threaded through the cannula and grasped by the endoscopic forceps or snare.

C. The endoscope is withdrawn with the guidewire. The gastrostomy tube is then attached to the guidewire.

D. The guidewire and tube are pulled back through the mouth, oesophagus and stomach to exit on the anterior abdominal wall, and the endoscope is repassed to confirm the site of placement of the retention device. The latter closely abuts the gastric mucosa; its position is maintained by an external fixation device (see inset). It is also possible to place PEG tubes using fluoroscopic guidance when endoscopy is difficult (radiologically inserted gastrostomy).

There is no evidence to recommend one technique over another, although the:-

Radiological method has advantages in patients with cancers of the head and neck undergoing potentially curative therapy (less chance of tumour ‘seeding’) and in those with poor respiratory reserve (such as motor neuron disease) since there is no endoscope to compress the upper airways. Reported outcomes are broadly similar for both and the choice of technique should be based on indications and contraindications, operator experience and facilities available.Most important is rigorous patient assessment and selection prior to gastrostomy placement, which should be done by a multidisciplinary nutrition support team, and avoided when the procedure may be too hazardous or the benefits are outweighed by the risks.

Complications of gastrostomy tube feeding

• Reflux of gastric contents and pulmonary aspiration (same as nasogastric tube)• Risks of insertion (pain, damage to intra-abdominal structures, intestinal perforation, pulmonary aspiration, infection, death)

• Risk of tumour ‘seeding’ if an endoscopic ‘pull-through’ technique is used in head and neck or oesophageal cancer patients

• Refeeding syndrome

Post-pyloric feeding

In patients with a high risk of pulmonary aspiration or gastroparesis, it may be preferable to feed into the jejunum (via a nasojejunal tube, gastrostomy with jejunal extension or direct placement into jejunum by radiological, endoscopic or laparoscopic means).Ethical and legal considerations in the management of artificial nutritional support

• Care of the sick involves the duty of providing adequate fluid and nutrients• Food and fluid should not be withheld from a patient who expresses a desire to eat and drink, unless there is a medical contraindication (e.g. risk of aspiration)

• A treatment plan should include consideration of nutritional issues and should be agreed by all members of the health-care team

• In the situation of palliative care, tube feeding should be instituted only if it is needed to relieve symptoms

5. Tube feeding is usually regarded in law as a medical treatment. Like other treatments, the need for such support should be reviewed on a regular basis and changes made in the light of clinical circumstances

6. A competent adult patient must give consent for any invasive procedures, including passage of a nasogastric tube or insertion of a central venous cannula

7. If a patient is unable to give consent, the health-care team should act in that person’s best interests, taking into account any wishes previously expressed by the patient and the views of family

8. Under certain specified circumstances (e.g. anorexia nervosa), it is appropriate to provide artificial nutritional support to the unwilling patient

Parenteral nutrition

This is usually reserved for clinical situations where the absorptive functioning of the intestine is severely impaired.In parenteral feeding, nutrition is delivered directly into a large-diameter systemic vein, completely bypassing the intestine and portal venous system.

As well as being more invasive, more expensive and less physiological than the enteral route, parenteral nutrition is associated with many more complications, mainly infective and metabolic (disturbances of electrolytes, hyperglycaemia).

To minimize risk to the patient, there should be Strict adherence to:-

• Aseptic practice in handling catheters• Careful monitoring of clinical (pulse, blood pressure and temperature) and

• Biochemical (urea, electrolytes, glucose and liver function tests) parameters.

Intravenous catheter complications

• Insertion (pneumothorax, haemothorax, arterial puncture)• Catheter infection (sepsis, discitis, pulmonary or cerebral abscess)

• Central venous thrombosis

Metabolic complications

• Refeeding syndrome

• Electrolyte imbalance

•Hyperglycaemia

•Hyperalimentation

•Fluid overload

• Hepatic steatosis/fibrosis/cirrhosis

Complications of parenteral nutrition

The parenteral route may be indicated for:-

1. Patients who are malnourished or at risk of becoming so

2. who have an inadequate or unsafe oral intake and a poorly functioning or non-functioning or perforated intestine or an intestine that cannot be accessed by tube feeding.

3. In practice, it is most often required in acutely ill patients with multi-organ failure or in severely under-nourished patients undergoing surgery.

It may offer a benefit over oral or enteral feeding prior to surgery in those who are severely malnourished when other routes of feeding have been inadequate. Parenteral nutrition following surgery should be reserved for when enteral nutrition is not tolerated or feasible or where complications (especially sepsis) impair gastrointestinal function, such that oral or enteral feeding is not possible for at least 7 days.

Intestinal failure (‘short bowel syndrome’)

Intestinal failure (IF) is defined as a:-reduction in the function of the gut below the minimum necessary for the absorption of macronutrients and/or water and electrolytes such that intravenous supplementation is required to support health and/or growth.

The term can be used only when there is both:

• a major reduction in absorptive capacity and• an absolute need for intravenous fluid support.

IF can be further classified according to its onset, metabolic consequences and expected outcome.

• Type 1 IF: an acute-onset, usually self-limiting condition with few long-term sequelae. It is most often seen following abdominal surgery or in the context of critical illness. Intravenous support may be required for a few days to weeks.

• Type 2 IF: far less common. The onset is also usually acute, following some intra-abdominal catastrophic event (ischaemia, volvulus, trauma or perioperative complication). Septic and metabolic problems are seen, along with complex nutritional issues. It requires multidisciplinary input (nursing, dietetic, medical, biochemical, surgical, radiological and microbiological) and support may be necessary for weeks to months.

Type 3 IF:

a chronic condition in which patients are metabolically stable but intravenous support is required over months to years.It may or may not be reversible

Magement

IF is a complex clinical problem with profound and wide-ranging physiological and psychological effects, which is best cared for by a dedicated multidisciplinary team. The majority of IF results from short bowel syndrome , with chronic intestinal dysmotility and chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction accounting for most of the remainder.

The severity of the physiological upset correlates well with how much functioning intestine remains (rather than how much has been removed).

Causes of short bowel syndrome in adults

• Mesenteric ischaemia• Post-operative complications

• Crohn’s disease

• Trauma

• Neoplasia

• Radiation enteritis

Measurement of the remaining small bowel (from the duodeno-jejunal flexure) at the time of surgery is essential for planning future therapy

The aims of treatment are to:

• Provide nutrition, water and electrolytes to maintain health with normal body weight (and allow normal growth in affected children)• Utilize the enteral or oral routes as much as possible

• Minimize the burden of complications of the underlying disease, as well as the IF and its treatment

• Allow a good quality of life.

If the ileum and especially the ileum and colon remain intact, long-term nutritional support can usually be avoided.

Unlike the jejunum, the ileum can adapt to increase absorption of water and electrolytes over time. The presence of the colon (part or wholly intact) further improves fluid absorption and can generate energy through production of short-chain fatty acids. It is therefore useful to classify patients with a short gut according to whether or not they have any residual colon.

Jejunum–colon patients

Those with an anastomosis between jejunum and residual colon (jejunum–colon patients) may look well in the days or initial weeks following the acute insult but develop protein-energy malnutrition and significant weight loss, becoming seriously under-nourished over weeks to months.

Stool volume is determined by oral intake, with higher intakes causing more diarrhoea and the potential for dehydration, sodium and magnesium depletion and acute renal failure. The absence of the ileum leads to deficiencies of vitamin B12 and fat-soluble vitamins.

The absorption of various drugs, including thyroxine, digoxin and warfarin, can be reduced.

Approximately 45% of patients will develop gallstones due to disruption of the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids, and 25% may develop calcium oxalate renal stones due to increased colonic absorption of oxalate.

Jejunostomy patients

Patients left with a stoma (usually a jejunostomy) behave very differently, although stool volumes are again determined by oral intake. The jejunum is intrinsically highly permeable, and in the absence of the ileum and its net absorptive role, high losses of fluid, sodium and magnesium dominate the clinical picture from the outset. Dehydration, hyponatraemia, hypomagnesaemia and acute renal failure are the most immediate problems but protein-energy malnutrition will also develop.The jejunum has no real potential for adaptation in terms of absorption, so it is essential to recognize and address the issues of dehydration and electrolyte disturbance early and not expect the problems to improve with time.

Management of short bowel patients (and ‘high-output’ stoma)

1. Accurate charting of fluid intake and losses• Vital: oral intake determines stool volume and should be restricted rather than encouraged

2. Dehydration and hyponatraemia

• Must first be corrected intravenously to restore circulating volume and reduce thirst

• Stool volume should be minimized and any ongoing fluid imbalance between oral intake and stool losses replenished intravenously

3. Measures to reduce stool volume losses

• Restrict oral fluid intake to ≤ 500 mL/24 hrs• Give a further 1000 mL oral fluid as oral rehydration solution containing 90–120 mmol Na/L (St Mark’s solution or Glucodrate, Nestlé)

• Slow intestinal transit (to maximise opportunities for absorption): Loperamide, codeine phosphate

• Reduce volume of intestinal secretions: Gastric acid: omeprazole 20 mg/day orally Other secretions: octreotide 50–100 μg 3 times daily by subcutaneous injection

4. Measures to increase absorption

• Teduglutide (a recombinant glucagon-like peptide 2) significantly reduces requirements for intravenous fluid and nutritional support

Small bowel and multivisceral transplantation

Long-term intravenous nutritional support remains the mainstay of therapy for chronic IF but has its own morbidity and mortality. The 10-year survival for patients on long-term home parenteral nutrition is approximately 90%.The majority of deaths are due to the underlying disease process but 5–11% will die from direct complications of parenteral nutrition itself (especially catheterrelated sepsis).

A minority of patients with chronic IF, for whom the safe administration of parenteral nutrition has become difficult or impossible, may benefit from small bowel transplantation .

The first successful small bowel transplant was carried out in 1988.

The introduction of tacrolimus allowed a satisfactory balance of immunosuppression, avoiding rejection while minimising sepsis.

Since then, over 2000 transplants have been performed worldwide. Survival rates continue to improve, for both isolated small bowel and multivisceral transplantation (small bowel along with a combination of liver and/or kidney and/ or pancreas), although major complications are still frequent .

Current 5-year survival rates are 50–80%, with better outcomes for younger patients and those receiving isolated small bowel procedures.

Potential indications for small bowel transplantation

Complications of central venous catheters• Central venous thrombosis leading to loss of two or more intravenous access points

• Severe or recurrent line sepsis

• Recurrent severe acute kidney injury related to dehydration

Metabolic complications of parenteral nutrition

• Parenteral nutrition-related liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and liver failure

Energy balance in old age

• Body composition: muscle mass is decreased and percentage of body fat increased.

• Energy expenditure: with the fall in lean body mass, basal metabolic rate is decreased and energy requirements are reduced.

• Weight loss: after weight gain throughout adult life, weight often falls beyond the age of 80 years. This may reflect decreased appetite, loss of smell and taste, and decreased interest in and financial resources for food preparation, especially after loss of a partner.

• Care of the sick involves the duty of providing adequate fluid and nutrients

• Food and fluid should not be withheld from a patient who expresses a desire to eat and drink, unless there is a medical contraindication (e.g. risk of aspiration)• A treatment plan should include consideration of nutritional issues and should be agreed by all members of the health-care team

Ethical and legal considerations in the management of artificial nutritional support

• In the situation of palliative care, tube feeding should be instituted only if it is needed to relieve symptoms

• Tube feeding is usually regarded in law as a medical treatment. Like other treatments, the need for such support should be reviewed on a regular basis and changes made in the light of clinical circumstances

A competent adult patient must give consent for any invasive procedures, including passage of a nasogastric tube or insertion of a central venous cannula

• If a patient is unable to give consent, the health-care team should act in that person’s best interests, taking into account any wishes previously expressed by the patient and the views of family

• Under certain specified circumstances (e.g. anorexia nervosa), it is appropriate to provide artificial nutritional support to the unwilling patient

BMI: less reliable in old age as height is lost (due to kyphosis, osteoporotic crush fractures, loss of intervertebral disc spaces).

Alternative measurements include arm demispan and knee height, which can be extrapolated to estimate height.

Artificial nutrition at the end of life

Rarely, assisted nutrition may not result in the expected outcomes of reversal of weight loss or improved quality and duration of life.It very seldom reverses other underlying health issues, although it may be used as a short term ‘bridge’ to help through a patient through a particular crisis.

Such scenarios may present when someone is approaching the end of life, or in the face of weight loss due to advanced respiratory or cardiac failure, malignancy or dementia

In selected cases, a decision not to intervene may be appropriate. An intervention that merely prolongs life without preserving or adding to its quality is seldom justified, particularly if the intervention is not without risk itself. Such decisions are not taken lightly and careful scrutiny of each case is necessary.

There should be a thoughtful and sensitive discussion explaining what artificial nutrition can and cannot achieve involving the multidisciplinary team looking after the patient as well as next of kin and, in some cases, legal representatives.

Nutrition and dementia

Weight loss is seen commonly in people with dementia, and nutritional and eating problems are a significant source of concern for those caring for them. It is appropriate to:• screen for malnutrition (e.g. MUST, see above)

• assess specific eating difficulties (e.g. Edinburgh Feeding Evaluation in Dementia questionnaire)

• monitor and document body weight

• encourage adequate intake of food

• use oral nutritional supplements.

However, the evidence that artificial nutritional support beyond oral supplementation improves overall functioning or prolongs life in dementia is absent or weak.Success is more likely in those with mild to moderate dementia, when a temporary and reversible crisis has been precipitated by some acute event.

It is important to remember that there is strong evidence to avoid tube feeding in those with advanced dementia because this improves neither the quality nor the duration of life.

Micronutrients, minerals and their diseases

VitaminsVitamins are organic substances with key roles in certain metabolic pathways, and are categorized into those that are:-

• Fat-soluble (vitamins A, D, E and K) and those that are

• Water-soluble (vitamins of the B complex group and vitamin C).

Recommended daily intakes of micronutrients vary between countries and the nomenclature has become potentially confusing.

In the UK, the ‘reference nutrient intake’ (RNI) has been calculated as the mean plus two standard deviations (SD) of daily intake in the population, which therefore describes normal intake for 97.5% of the population.

The lower reference nutrient intake (LRNI) is the mean minus 2 SD, below which would be considered deficient in most of the population.

These dietary reference values (DRV) have superseded the terms RDI (recommended daily intake) and RDA (recommended daily amount). Other countries use different terminology.

Additional amounts of some micronutrients may be required in pregnancy and lactation.

Nutrition in pregnancy and lactation

• Energy requirements: increased in both mother and fetus but can be met through reduced maternal energy expenditure.• Micronutrient requirements: adaptive mechanisms ensure increased uptake of minerals in pregnancy, but extra increments of some are required during lactation.

.

Additional increments of some vitamins are recommended during pregnancy and lactation:

Vitamin A: for growth and maintenance of the fetus, and to provide some reserve (important in some countries to prevent blindness associated with vitamin A deficiency). Teratogenic in excessive amounts.Vitamin D: to ensure bone and dental development in the infant. Higher incidences of hypocalcaemia, hypoparathyroidisim and defective dental enamel have been seen in infants of women not taking vitamin D supplements at > 50° latitude.

Folate: taken pre-conceptually and during the first trimester, reduces the incidence of neural tube defects by 70%.

Vitamin B12: in lactation only.

Thiamin: to meet increased fetal energy demands. Riboflavin: to meet extra demands.

Niacin: in lactation only.

Vitamin C: for the last trimester to maintain maternal stores as fetal demands increase.

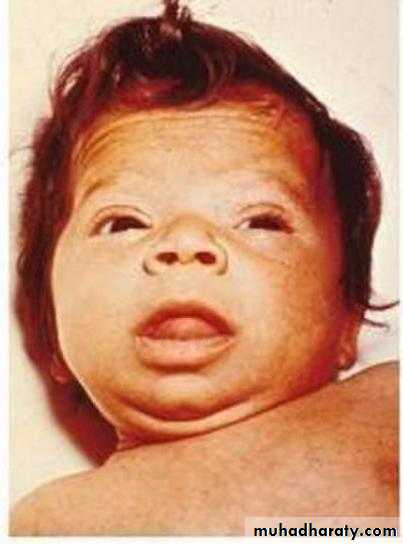

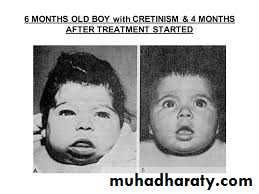

Iodine: in countries with high consumption of staple foods (e.g. brassicas, maize, bamboo shoots) that contain goitrogens (thiocyanates or perchlorates) that interfere with iodine uptake, supplements prevent infants being born with cretinism

Vitamin deficiency diseases are most prevalent in developing countries but still occur in developed countries.

Older people and alcoholics are at risk of deficiencies in B vitamins and in vitamins D and C.

Nutritional deficiencies in pregnancy can affect either the mother or the developing fetus, and extra increments of vitamins are recommended in the UK.

Darker-skinned individuals living at higher latitude, and those who cover up or do not go outside are at increased risk of vitamin D deficiency due to inadequate sunlight exposure.

Dietary supplements are recommended for these ‘at-risk’ groups. Some nutrient deficiencies are induced by diseases or drugs. Deficiencies of fat-soluble vitamins are seen in conditions of fat malabsorption.