Lec:3

Prof.Dr.Maha AlYasiri

HEMOSTASIS AND THROMBOSIS

Normal hemostasis comprises a series of regulated processes that culminate in the formation of a blood clot that limits bleeding from an injured vessel.

The pathologic counterpart of hemostasis is thrombosis, the formation of blood clot (thrombus) within non-traumatized, intact vessels.

This discussion begins with normal hemostasis and its regulation, to be followed by causes and consequences of thrombosis.

Normal Hemostasis

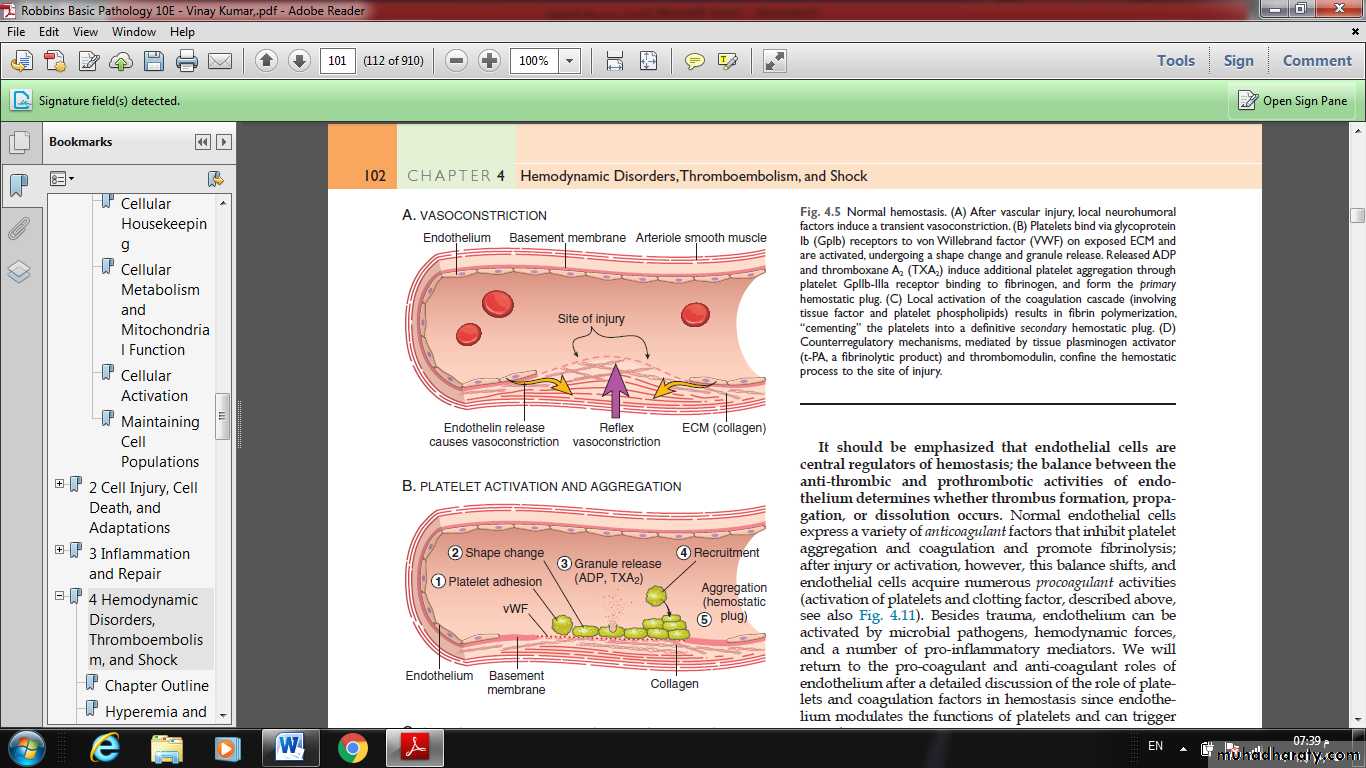

Hemostasis is a precisely orchestrated process involving platelets, clotting factors, and endothelium that occurs at the site of vascular injury and culminates in the formation of a blood clot, which serves to prevent or limit the extent of bleeding.The general sequence of events leading to hemostasis at a site of vascular injury:

(A) After vascular injury, local neurohumoral factors induce a transient vasoconstriction.

(B) Primary hemostasis: the formation of the platelet plug. Platelets bind via glycoprotein Ib (GpIb) receptors to von Willebrand factor (VWF) on exposed ECM and are activated, undergoing a shape change (from small rounded discs to flat plates with spiky protrusions that markedly increased surface area) and granule release. Within minutes the secreted products recruit additional platelets, which undergo aggregation to form a primary hemostatic plug.

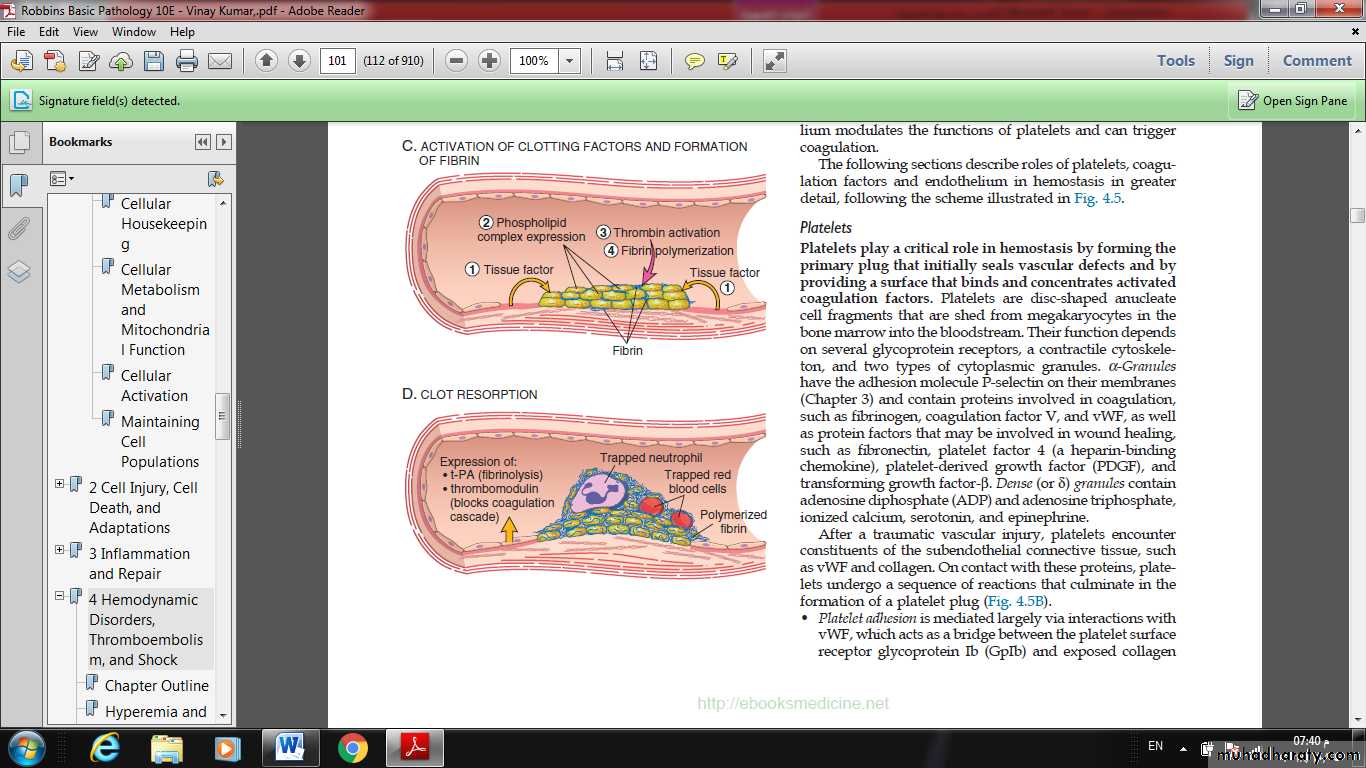

(C) Secondary hemostasis: deposition of fibrin. Vascular injury

exposes tissue factor at the site of injury. Tissue factor is a glycoprotein that is normally expressed by subendothelial cells in the vessel wall, such as smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts. Tissue factor binds and activates factor VII, setting motion a cascade of reactions that culiminates in thrombin generation. Thrombin cleaves circulating fibrinogen into insoluble fibrin, creating a fibrin meshwork, and also is a potent activator of platelets, leading to additional platelet aggregation at the site of injury. This sequence, referred to as secondary hemostasis, consolidates the initial platelet plug definitive secondary hemostatic plug.

(D) Clot stabilization and resorption. Polymerized fibrin and platelet aggregates undergo contraction to form a solid, permanent plug that prevents further hemorrhage. At this stage, counterregulatory mechanisms (e.g., tissue plasminogen activator, t-PA made by endothelial cells) are set into motion that limit clotting to the site of injury and eventually lead to clot resorption and tissue repair.

Fig. Normal hemostasis.

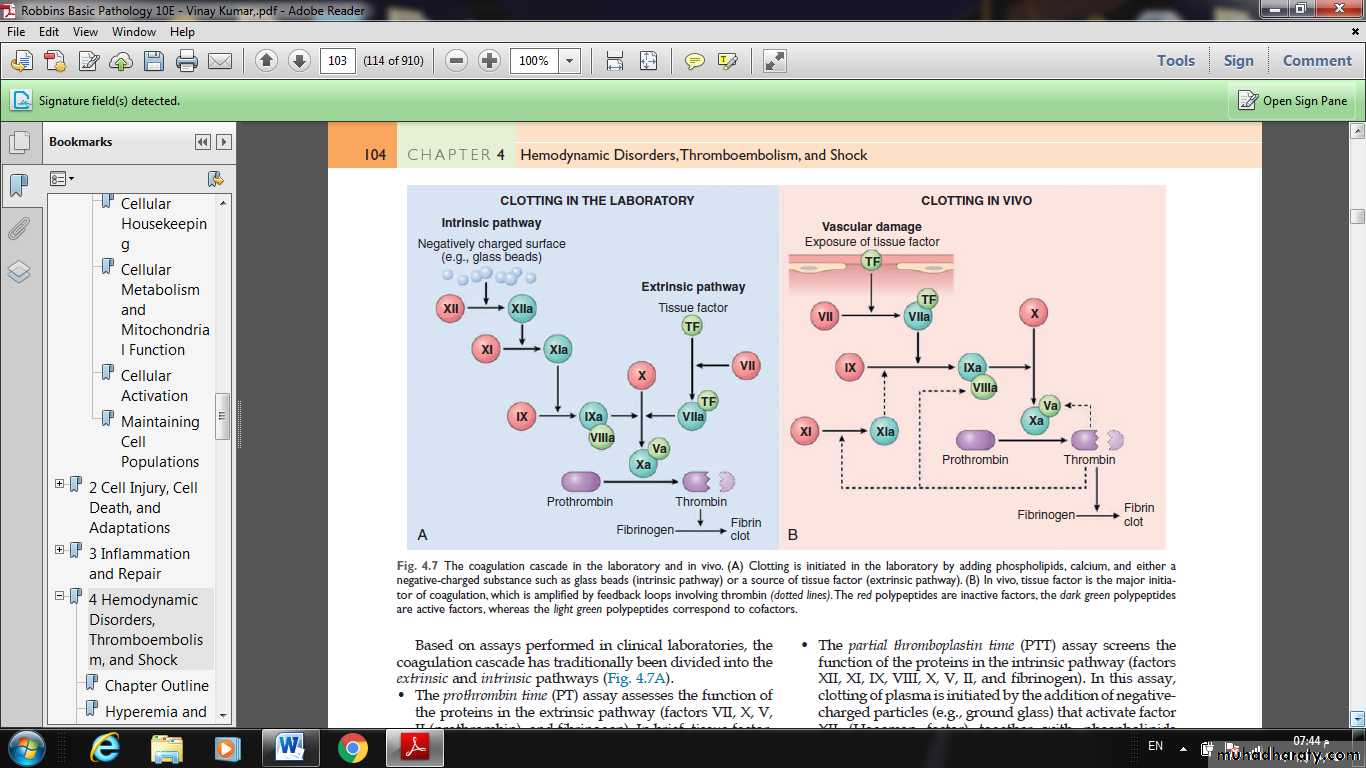

Fig. The coagulation cascade in the laboratory and in vivo. (A) Clotting is initiated in the laboratory by adding phospholipids, calcium, and either a negative-charged substance such as glass beads (intrinsic pathway) or a source of tissue factor (extrinsic pathway). (B) In vivo, tissue factor is the major initiator of coagulation, which is amplified by feedback loops involving thrombin (dotted lines). The red polypeptides are inactive factors, the dark green polypeptides are active factors, whereas the light green polypeptides correspond to cofactors.

Thrombosis

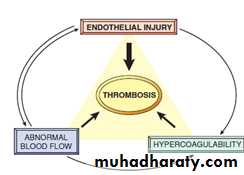

The pathologic counterpart of hemostasis is thrombosis, the formation of blood clot (thrombus) within non-traumatized, intact vessels.The primary abnormalities that lead to intravascular thrombosis are:

(1) endothelial injury,

(2) stasis or turbulent blood flow, and

(3) hypercoagulability of the blood

(the so-called “Virchow triad”).

Thrombosis underlies the most serious and common forms of cardiovascular disease.

Fig. Virchow’s triad in thrombosis. Endothelial integrity is the most important factor. Abnormalities of procoagulants or anti-coagulants can tip the balance in favor of thrombosis. Abnormal blood flow (stasis or turbulence) can lead to hypercoagulability directly and also indirectly through endothelial dysfunction.

Endothelial injury

Endothelial injury leading to platelet activation.underlies thrombus formation in the heart and the arterial circulation, where the high rates of blood flow impede clot formation by preventing platelet adhesion or diluting coagulation factors.

severe endothelial injury may trigger thrombosis by exposing VWF and tissue factor.

Most common examples are:

#Endocardial injury during myocardial infarction.

#Injury over ulcerated plaque in severely atherosclerotic arteries.

#vasculitis.

Abnormal Blood Flow

Turbulence (chaotic blood flow) contributes to arterial and cardiac thrombosis by causing endothelial injury or dysfunction, as well as by forming countercurrents and local pockets of stasis.Stasis is a major factor in the development of venous thrombi.

Under conditions of normal laminar blood flow, platelets (and other blood cells) are found mainly in the center of the vessel lumen, separated from the endothelium by a slower-moving layer of plasma.

By contrast, stasis and turbulence have the following deleterious

effects:

• Both promote endothelial cell activation and enhanced procoagulant activity.

• Stasis allows platelets and leukocytes to come into contact with the endothelium when the flow is sluggish.

• Stasis also slows the washout of activated clotting factors and impedes the inflow of clotting factor inhibitors.

Turbulent and static blood flow contributes to thrombosis in a number of clinical settings.

Ulcerated atherosclerotic plaques not only expose subendothelial ECM but also cause turbulence.

Abnormal aortic and arterial dilations called aneurysms create local stasis and consequently are fertile sites for thrombosis .

Acute myocardial infarction results in focally noncontractile myocardium. Ventricular remodeling after more remote infarction can lead to aneurysm formation. In both cases, cardiac mural thrombi are more easily formed because of the local blood stasis.

Mitral valve stenosis (e.g., after rheumatic heart disease) results in left atrial dilation. In conjunction with atrial fibrillation, a dilated atrium also produces stasis and is a prime location for the development of thrombi.

Hyperviscosity syndromes (such as polycythemia vera,) increase resistance to flow and cause small vessel stasis;

sickle cell anemia the deformed red cells cause vascular occlusions, and the resultant stasis also predisposes to thrombosis.

Hypercoagulability

Hypercoagulability refers to an abnormally high tendency of the blood to clot, and is typically caused by alterations in coagulation factors.

It contributes infrequently to arterial or intracardiac thrombosis but is an important underlying risk factor for venous thrombosis.

The alterations of the coagulation pathways that predispose affected persons to thrombosis can be divided into primary (genetic) and secondary (acquired) disorders.

Primary (Genetic)

Common (>1% of the Population)

Factor V mutation

Prothrombin mutation

Increased levels of factor VIII, IX, or XI or fibrinogen

Rare

Anti-thrombin III deficiency

Protein C deficiency

Protein S deficiency

Secondary (Acquired)

Prolonged bed rest or immobilizationMyocardial infarction

Atrial fibrillation

Tissue injury (surgery, fracture, burn)

Cancer

Prosthetic cardiac valves

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

Anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome

MORPHOLOGY

Thrombi can develop anywhere in the cardiovascular system.

Arterial or cardiac thrombi typically arise at sites of endothelial injury or turbulence;

venous thrombi characteristically occur at sites of stasis.

Thrombi are focally attached to the underlying vascular surface and tend to propagate toward the heart; thus, arterial thrombi grow in a retrograde direction from the point of attachment, whereas venous thrombi extend in the direction of blood flow.

The propagating portion of a thrombus tends to be poorly attached and therefore prone to fragmentation and migration through the blood as an embolus.

Thrombi can have grossly (and microscopically) apparent laminations called lines of Zahn; these represent pale platelet and fibrin layers alternating with darker red cell–rich layers. Such lines are significant in that they are only found in thrombi that form in flowing blood; their presence can therefore usually distinguish antemortem thrombosis from the bland nonlaminated clots that form in the postmortem state.

Although thrombi formed in the “low-flow” venous system superficially resemble postmortem clots, careful evaluation generally shows ill-defined laminations.

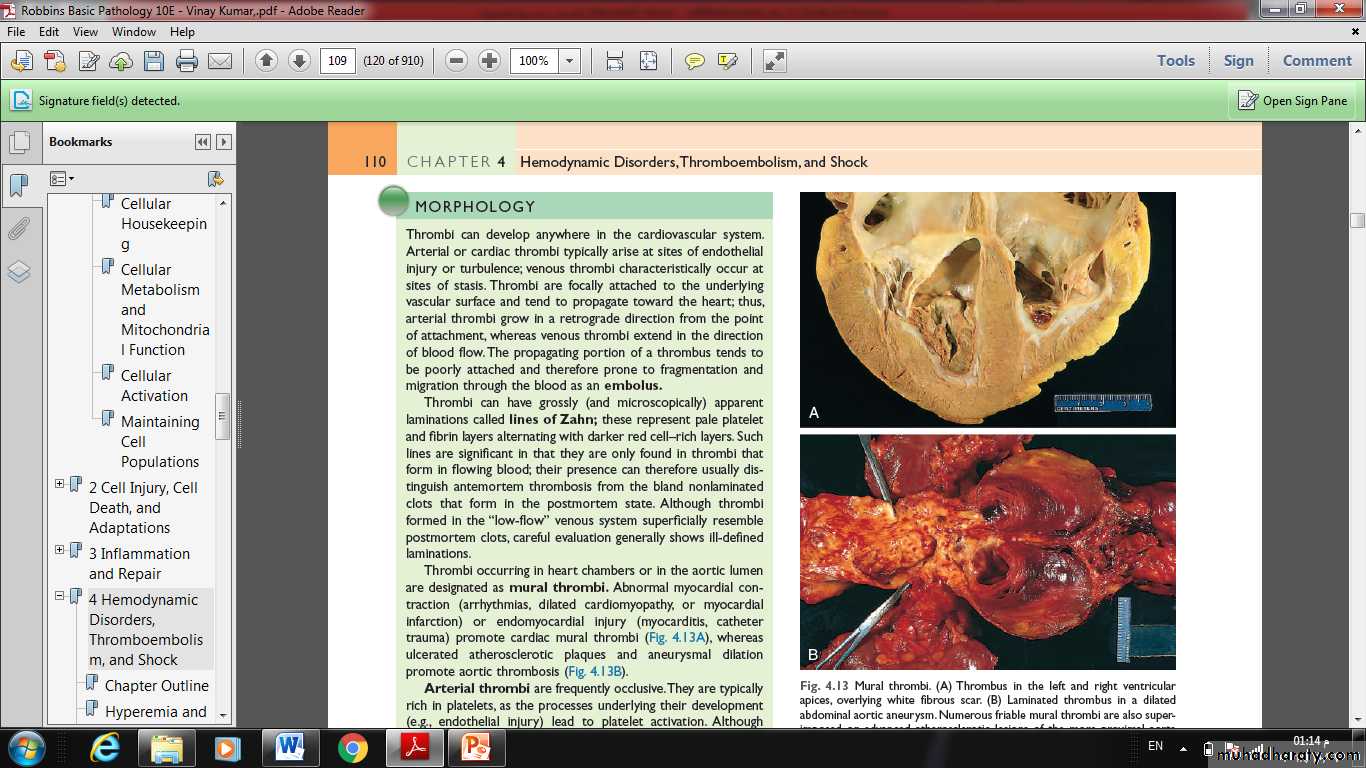

Thrombi occurring in heart chambers or in the aortic lumen are designated as mural thrombi.

Arterial thrombi are frequently occlusive. They are typically rich in platelets, as the processes underlying their development (e.g., endothelial injury) lead to platelet activation. Although usually superimposed on a ruptured atherosclerotic plaque, other vascular injuries (vasculitis, trauma) can also be underlying causes.

Venous thrombi (phlebothrombosis) are almost invariably occlusive; they frequently propagate some distance toward the heart, forming a long cast within the vessel lumen that is prone to give rise to emboli. Because these thrombi form in the sluggish venous circulation, they tend to contain more enmeshed red cells, leading to the moniker red, or stasis, thrombi. The veins of the lower extremities are most commonly affected (90% of venous thromboses

At autopsy, postmortem clots can sometimes be mistake for venous thrombi. However, the former are:

gelatinous

and because of red cell settling they have a dark red dependent portion and a yellow “chicken fat” upper portion;

they also are usually not attached to the underlying vessel wall.

By contrast, red thrombi typically are:

firm,

focally attached to vessel walls,

and the contain gray strands of deposited fibrin.

Thrombi on heart valves are called vegetations.

Fig. Mural thrombi. (A) Thrombus in the left and right ventricular apices, overlying white fibrous scar. (B) Laminated thrombus in a dilated abdominal aortic aneurysm. Numerous friable mural thrombi are also superimposed on advanced atherosclerotic lesions of the more proximal aorta (left side of photograph).