LIVER

INTRODUCTIONThe liver is the largest organ in the body, weighing 1.5 kg in theaverage 70-kg man. The liver parenchyma is entirely covered bya thin capsule and by visceral peritoneum on all but the posteriorsurface of the liver, termed the ‘bare area’. The liver is dividedinto a large right lobe, which constitutes three-quarters of theliver parenchyma, and a smaller left lobe.ANATOMY OF THE LIVERLigaments and peritoneal reflectionsThe liver is fixed by ligament ,On the superior surface of the left lobeis the left triangular ligament. Dividing the anterior and posteriorfolds of this ligament allows the left lobe to be mobilised from thediaphragm and the left lateral wall of the inferior vena cava (IVC)to be exposed. The right triangular ligament fixes the entire rightlobe of the liver to the undersurface of the right hemidiaphragm.. Another major supporting structure is the falciform ligament (remnant of the umbilicalvein), which runs from the umbilicus to the liver between theright and left lobes, passing into the interlobar fissure. From thefissure, it passes anteriorly on the surface of the liver, attaching itto the posterior aspect of the anterior abdominal wall. Division ofthe superior leaves of the falciform ligament allows exposure of thesuprahepatic IVC, lying within a thin sheath of fibrous tissue. Thefinal peritoneal reflection is between the stomach and the liver.This lesser omentum is often thin and fragile, but contains thehilar structures in its free edge

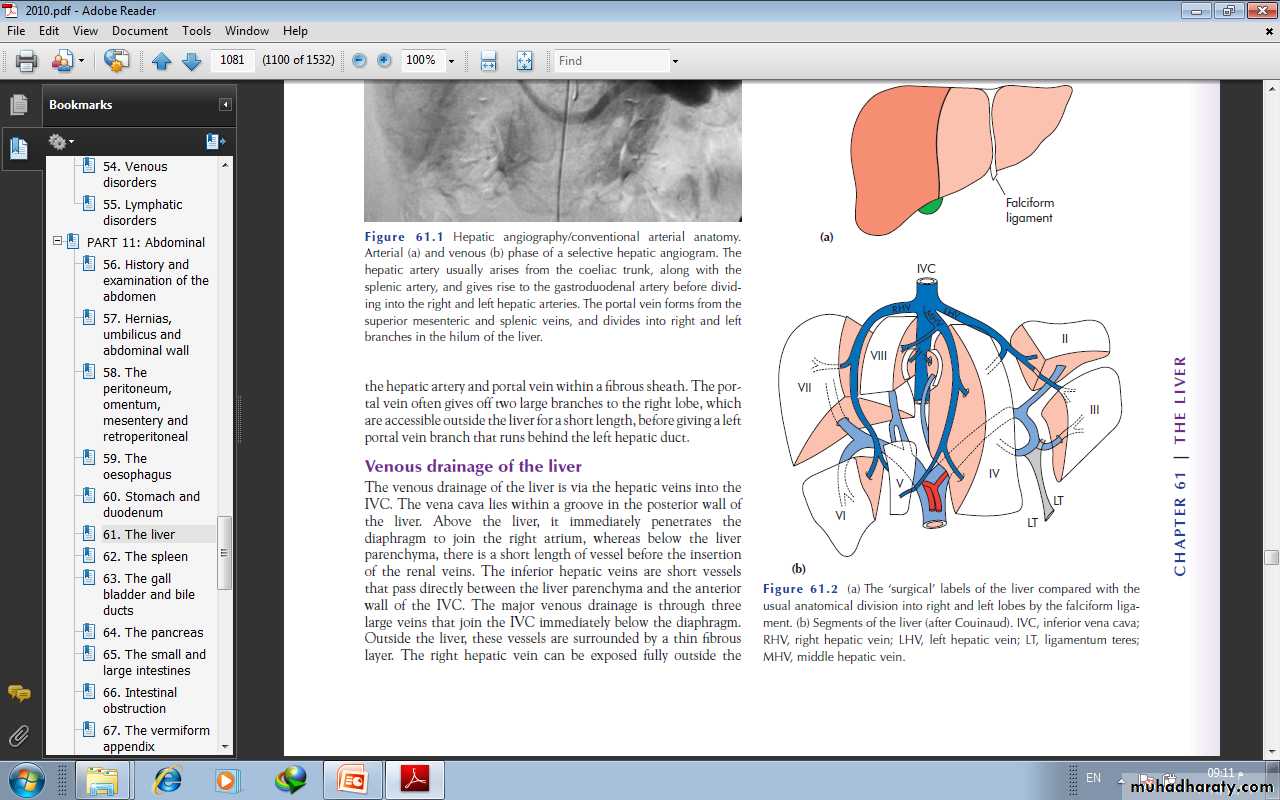

Liver blood supplyThe blood supply to the liver is unique, 80% being derived fromthe portal vein and 20% from the hepatic artery. The arterialblood supply in most individuals is derived from the coeliac trunkof the aorta, where the hepatic artery arises along with the splenicartery. After supplying the gastroduodenal artery, it branches at avery variable level to produce the right and left hepatic arteries.The right artery supplies the majority of the liver parenchyma andis therefore the larger of the two arteries. There are manyanatomical variations.

Structures in the hilum of the liverThe hepatic artery, portal vein and bile duct are present withinthe free edge of the lesser omentum or the ‘hepatoduodenal ligament’.. The usual anatomicalrelationship of these structures is for the bile duct to be within thefree edge, the hepatic artery to be above and medial, and theportal vein to lie posteriorly. Multiple small hepatic arterial branchesprovide blood to the bile duct, principally from the right hepaticartery. The portal vein arises from the confluence of the splenicvein and the superior mesenteric vein behind the neck of thepancreas. It has some important tributaries, including the leftgastric vein which joins just above the pancreas.

Venous drainage of the liverThe venous drainage of the liver is via the hepatic veins into theIVC. The vena cava lies within a groove in the posterior wall ofthe liver. Above the liver, it immediately penetrates thediaphragm to join the right atrium, whereas below the liverparenchyma, there is a short length of vessel before the insertionof the renal veins. The major venous drainage is through threelarge veins that join the IVC immediately below the diaphragm. The right kidney and adrenal gland lie immediatelyadjacent to the retrohepatic IVC. The right adrenal veindrains into the IVC at this level, usually via one main branch.

Segmental anatomy of the liver Couinaud, a French anatomist, described the liver as being divided into eight segments . Each ofthese segments can be considered as a functional unit, with abranch of the hepatic artery, portal vein and bile duct, anddrained by a branch of the hepatic vein. The overall anatomy ofthe liver is divided into a functional right and left along the linebetween the gall bladder fossa and the middle hepatic vein(Cantlie’s line). Liver segments (V–VIII), to the right of this line,are supplied by the right hepatic artery and the right branch ofthe portal vein, and drain bile via the right hepatic duct. To theleft of this line (segments I–IV), functionally, is the left liver,which is supplied by the left branch of the hepatic artery and theleft portal vein branch, and drains bile via the left hepatic duct.

Liver function and testsAdequate liver function is essential to survival; humans willsurvive for only 24–48 hours in the anhepatic state.Main functions of the liver■ Maintaining core body temperature■ pH balance and correction of lactic acidosis■ Synthesis of clotting factors■ Glucose metabolism, glycolysis and gluconeogenesis■ Urea formation from protein catabolism■ Bilirubin formation from haemoglobin degradation■ Drug and hormone metabolism■ Removal of gut endotoxins and foreign antigens

Routinely tests of liver functionTest Normal rangeBilirubin 5–17 μmol l–1Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 35–130 IU l–1Aspartate transaminase (AST) 5–40 IU l–1Alanine transaminase (ALT) 5–40 IU l–1Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) 10–48 IU l–1Albumin 35–50 g l–1Prothrombin time (PT) 12–16 s

Bilirubin is synthesised in the liver and excreted in the bile.Increased levels may be associated with increased haemoglobinbreakdown, hepatocellular dysfunction resulting in impairedbilirubin transport and excretion, or biliary obstruction. Inpatients with known parenchymal liver disease, progressive elevationof bilirubin in the absence of a secondary complication suggestsdeterioration in liver function. The serum alkalinephosphatase is particularly elevated with cholestatic liver diseaseor biliary obstruction. The transaminase levels [aspartatetransaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT)] reflectacute hepatocellular damage, as does the gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase (GGT) level, which may be used to detect theliver injury associated with acute alcohol ingestion. The syntheticfunctions of the liver are reflected in the ability to synthesiseproteins (albumin level) and clotting factors (prothrombin time).The standard method of monitoring liver function in patientswith chronic liver disease is serial measurement of bilirubin,albumin and prothrombin time.

Clinical signs of impaired liver functionThese signs depend on the severity of dysfunction and whether itis acute or chronic.Acute liver failureCauses of acute liver failure■ Viral hepatitis (hepatitis A, B, C, D, E)■ Drug reactions [halothane, isoniazid–rifampicin,, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs]■ Paracetamol overdose■ Mushroom poisoning■ Shock and multiorgan failure■ Acute Budd–Chiari syndrome■ Wilson’s disease■ Fatty liver of pregnancy

In the early stages there may be no objective signs, but with severedysfunction the onset of clinical jaundice may be associated withneurological signs of liver failure, consisting of a liver flap, drowsiness,confusion and, eventually, coma

Treatment of acute liver failureThe overall mortality from acute liver failure is approximately50%, even with the best supportive therLiver transplantation is appropriate for some patients with acute liver failure , although the overall results are Supportive therapy for acute liver failure■ Fluid balance and electrolytes■ Acid–base balance and blood glucose monitoring■ Nutrition■ Renal function (haemofiltration)■ Respiratory support (ventilation)■ Monitoring and treatment of cerebral oedema■ Treat bacterial and fungal infectionpoor in comparison with liver transplantation for chronic liver disease.

Chronic liver diseaseLethargy and weakness are common features irrespective of theunderlying cause. This often precedes clinical jaundice, whichindicates the liver’s inability to metabolise bilirubin. The serumbilirubin level reflects the severity of the underlying liver disease.Progressive deterioration in liver function is associated with ahyperdynamic circulation involving a high cardiac output, largepulse volume, low blood pressure and flushed warm extremities.Fever is a common feature, which may be related to underlyinginflammation and cytokine release from the diseased liver or maybe due to bacterial infection, to which patients with chronic liverdisease are predisposed. Skin changes may be evident, includingspider naevi, cutaneous vascular abnormalities that blanch onpressure, palmar erythema and white nails (leuconychia).Endocrine abnormalities are responsible for hypogonadism andgynaecomastia.

The mental derangement associated with chronic liver disease is termed ‘hepatic encephalopathy’. This is associated with memory impairment, confusion, personality changes, altered sleep patterns and slow, slurred speech. The most useful clinical sign is the flapping tremor demonstrated byasking the patient to extend his or her arms and hyperextend the wrist joint. Abdominal distension due to ascites is a common late feature. This may be suggested clinically by the demonstration of a fluid thrill or shifting dullness. Protein catabolism produces loss of muscle bulk and wasting, and a coagulation defect is suggested by the presence of skin bruising.

Child’s classification of hepatocellular function in cirrhosisGroup designation A B CBilirubin (mg dl–1) < 2.0 2.0–3.0 > 3.0Albumin (g dl–1) > 3.5 3.0–3.5 < 3.0Ascites None Easily Poorly controlled controlled Neurological disorder None Minimal AdvancedNutrition Excellent Good Wasting

IMAGING THE LIVERUltrasoundThis is the first-line test owing to its safety and availability. It isentirely operator dependent. It is useful for determining bile ductdilatation, the presence of gallstones and the presenceof liver tumours. Doppler ultrasound allows flow in the hepaticartery, portal vein and hepatic veins to be assessed. Ultrasound is useful inguiding the percutaneous biopsy of a liver lesion.

Computerised tomographyThe current ‘gold standard’ for liver imaging is , multislice, spiral computerised tomography (CT). This provides fine detail of liver lesions down to less than 1 cm in diameter and gives information on their nature . Oral contrast enhancement allows visualisation of the stomach and duodenum in relation to the liver hilum. The early arterial phase of the intravenous contrast vascular enhancement is particularly useful for detecting small liver cancers, owing to their preferential arterial blood supply.

Magnetic resonance imagingMagnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is as CT. It does, however, offer several advantages.First, the use of iodine-containing intravenous contrastagents is precluded in many patients because of a history ofallergy. These patients should be offered MRI rather than contrastCT. Second, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography(MRCP) provides excellent quality, non-invasive imagingof the biliary tract. The image quality is currently below thatavailable from endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography(ERCP) or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC),Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) similarlyprovides high-quality images of the hepatic artery and portalvein, without the need for arterial cannulation. It is used as analternative to selective hepatic angiography for diagnosis.

Endoscopic retrogradecholangiopancreatographyERCP is required in patients with obstructivejaundice who cannot undergo MRCP because of claustrophobiaor where an endoscopic interventionpreoperative check of coagulation is essential, along with prophylacticantibiotics and an explanation of the main complications,which include pancreatitis, cholangitis and bleeding or perforationof the duodenum related to sphincterotomy.Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiographyPTC is indicated where endoscopic cholangiography has failed oris impossible, e.g. in patients with previous pancreatoduodenectomyor Pَlya gastrectomy. It is often required in patients withhilar bile duct tumours to guide external drainage of the bileducts to relieve jaundice and to direct stent insertion.

AngiographySelective visceral angiography may berequired for diagnostic purposes but, with improving cross-sectionalimaging (CT and MR angiography), is usually employed fortherapeutic intervention. Prior to liver resection, it may be usedto visualise the anatomy of the hepatic artery to the right and leftsides of the liver and to confirm patency or tumour involvementof the portal vein. Therapeutic interventionsinclude the occlusion of arteriovenous malformations, theembolisation of bleeding sites in the liver and the treatment ofliver tumours (transarterial embolisation, TAE

Nuclear medicine scanningRadioisotope scanning can provide diagnostic information thatcannot be obtained by other imaging modalities. Iodoida is atechnetium-99m (99mTc)-labelled radionuclide that is administeredintravenously, removed from the circulation by the liver,processed by hepatocytes and excreted in the bile. Imaging undera gamma camera allows its uptake and excretion to be monitoredin real time. These useful when a bile leak orbiliary obstruction is suspected and a non-invasive screening testis required. A sulphur colloid liver scan allows Kupffer cell activityin the liver to be determined. This may be particularly useful toconfirm the nature of a liver lesion; adenomas and haemangiomaslack Kupffer cells and hence show no uptake of sulphur colloid.

Laparoscopy and laparoscopic ultrasoundLaparoscopy is useful for the staging of hepatopancreatobiliarycancers. Lesions overlooked by conventional imaging are mainlyperitoneal metastases and superficial liver tumours. Laparoscopic ultrasound provides additional information for liver tumours on their proximity to the major vessels and bile duct .

LIVER TRAUMAGeneralLiver injuries are fortunately uncommon because of the positionof the liver under the diaphragm where it is protected by thechest wall.Liver trauma can be divided into blunt and penetrating injuries.Blunt injury produces contusion, laceration and avulsion injuries tothe liver, often in association with splenic, mesenteric or renal injury.Penetrating injuries, such as stab and gunshot wounds, are often associatedwith chest or pericardial involvement

Diagnosis of liver injuryThe liver is an extremely well-vascularised organ, and blood lossis therefore the major early complication of liver injuries. Clinicalsuspicion of a possible liver injury is essential, as a laparotomy byan inexperienced surgeon with inadequate preparation preoperativelyis doomed to failure. All lower chest and upper abdominalstab wounds should be suspect, especially if considerable bloodvolume replacement has been required. Similarly, severe crushinginjuries to the lower chest or upper abdomen often combine ribfractures, haemothorax and damage to the spleen and/or liver.Patients with a penetrating wound will require a laparotomyand/or thoracotomy once active resuscitation is under way

AscitesThe accumulation of free peritoneal fluid is a common feature ofadvanced liver disease independent of the aetiology. The fluidaccumulation is usually associated with abdominal discomfortand a dragging sensation. Development is usually insidious.

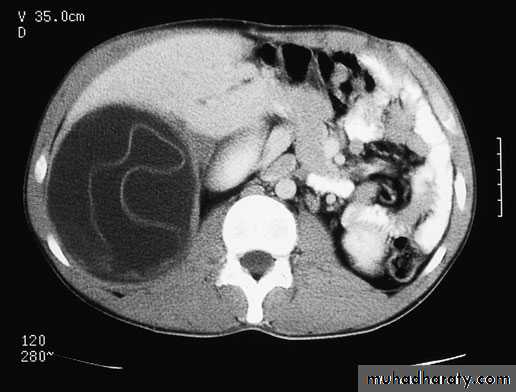

ManagementImaging by CT or ultrasound will confirm the ascites and demonstrate the irregularand shrunken nature of a cirrhotic liver and associated splenomegaly. Intravenous contrast enhancement will allow abdominal varices to be demonstrated and patency of the portal vein, as portal vein thrombosis is a common predisposing factorto the development of ascites in chronic liver disease. In patients without evidence of liver disease, malignancy is a common cause, and the primary site may also be established on CT.

Aspiration of the peritoneal fluid allows the measurement of protein content to determine whether the fluid is an exudate or transudate, and anamylase estimation to exclude pancreatic ascites. Cytology willdetermine the presence of cancerous cells, and both microscopyand culture will exclude primary bacterial peritonitis and tuberculousperitonitis. Urinary sodium excretion is used as a guide todiuretic therapy in cirrhosis.

Treatment of ascites in chronic liver diseaseThe initial treatment is to restrict additional salt intake and commence diuretics using either spironolactone or furosemide. This should be combined with advice on avoiding any precipitating factors for impaired liver function, such as alcohol intake in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Patients on diuretics should be monitored for the development of hyponatraemia andhypokalaemia. Abdominal paracentesisPatients who fail to respond to diuretic treatment may requirerepeated percutaneous aspiration of the ascites ,combined with volume replacement using salt-poor orstandard human albumin solution, dependent on the serumsodium level.Paracentesis provides only short-term symptomatic relief.

Peritoneovenous shuntingThe Le Veen shunt is designed for the relief of ascites due tochronic liver disease. One end of the silastic tube is inserted intothe ascites within the peritoneal cavity and the other end is tunnelledsubcutaneously to the neck, where it is inserted underdirect vision into the internal jugular vein and fed into the SVC.

TIPSS for ascites The use of TIPSS for ascites is for symptomatic relief, and the procedure is associated with considerable risks,including death from haemorrhage, renal failure or heart failure.Post-stent encephalopathy is common , and the majority of stents will stenose on follow-up.

Liver transplantation for ascitesDiuretic-resistant ascites is an indication for liver transplantationif associated with deterioration in liver function (rising bilirubin,dropping albumin, prolonged prothrombin time). The patient’s age, underlying aetiology of liver disease and associated medical problems will be the major factors determining suitability for liver transplantation

CHRONIC LIVER CONDITIONS:-1:Budd–Chiari syndromeThis is a condition principally affecting young females, in whichthe venous drainage of the liver is occluded by hepatic venousthrombosis or obstruction from a venous web. As a result of venous outflow obstruction, the liver becomes acutely congested,with the development of impaired liver function and, subsequently,portal hypertension, ascites and oesophageal varices.presentationacute thrombosis, the patient may rapidly progress to fulminantliver failure but, in the majority of cases, abdominal discomfortand ascites are the main presenting features. chronic, the liver progresses to established cirrhosis. The cause of the venous thrombosis needs to be established, and an underlying myeloproliferative disorder or pro-coagulant state is commonly found, such as anti-thrombin 3, protein C or protein S deficiency.

The diagnosis is commonly suspected in a patient presenting withascites, in whom a CT scan shows a large congested liver (earlystage, or a small cirrhotic liver in which there is grossenlargement of segment I (the caudate lobe). IVC compressionor occlusion from the segment I hypertrophy is also a commonfeature, as is thrombosis of the portal vein. Confirmation of thesuspected diagnosis is by hepatic venography via a transjugularapproach, which demonstrates occlusion of the hepatic veins andmay allow a transjugular biopsy.

Treatment of BCS Patients presenting in fulminant liver failure should be considered for livertransplantation, as should those with established cirrhosis andthe complications of portal hypertension. Those in whom cirrhosis is not established may be considered for portosystemic shunting by TIPSS, portocaval shunt or mesoatrial shunting. IVCcompression may be relieved by the insertion of a retrohepaticexpandable metallic stent. If the BCS is treated satisfactorily, theprognosis of this patient group is largely dependent on the underlyingaetiology and whether this is amenable to treatment. Patients are usually left on lifelong anticoagulation with warfarin.

2:Primary sclerosing cholangitis3:Primary biliary cirrhosisAs with PSC, the presentation of patients with primary biliarycirrhosis (PBC) is often hidden, with general malaise, lethargyand pruritus prior to the development of clinical jaundice or thefinding of abnormal liver function tests. The condition is largelyconfined to females. Diagnosis is suggested by the finding of circulatinganti-smooth muscle antibodies and, if necessary, is confirmedby liver biopsy. The condition is slowly progressive, withdeterioration in liver function resulting in lethargy and malaise. Itmay be complicated by the development of portal hypertensionand the secondary complications of ascites and variceal bleeding.The mainstay of treatment is liver transplantation.3:Caroli’s disease

5-Simple cystic diseaseLiver cysts are a common coincidental finding in patients undergoingabdominal ultrasound. Radiological findings to suggest thata cyst is simple are that it is regular, thin walled and unilocular,with no surrounding tissue response and no variation in densitywithin the cyst cavity. If these criteria are confirmed and the cystis asymptomatic, no further tests or treatment are required. Largecysts may be associated with symptoms of abdominal discomfort,possibly related to stretching of the overlying liver capsule.Aspiration alone is usually associated with cyst and symptomrecurrence, in which case more definitive treatment is required.Laparoscopic de-roofing is the treatment of choice for large symptomaticcysts and is associated with good long-term symptomaticrelief.

6-Polycystic liver diseaseThis is a congenital abnormality associated with cyst formationwithin the pancreas and kidney. Those associated with renal cysts may haveautosomal dominant inheritance. The cysts are often asymptomaticand incidental findings on ultrasound. They usually have no effect on organ function and require no specific treatment. pain often indicates haemorrhage into a cyst, which may be confirmed by ultrasound or CT scan. Cyst discomfort that is not controlled by oral analgesics may be treated by openor laparoscopic fenestration of the liver cysts.

LIVER INFECTIONSViral hepatitisViral hepatitis is a major world health problem.hepatitis A, B and C, other hepatitis viruses have been isolated,including hepatitis D, which is usually detected only in patientswith hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and hepatitis E, whichproduces a self-limiting hepatitis due to faeco-oral spread similarto hepatitis A .Hepatitis A presents with anorexia, weakness and generalmalaise for several weeks prior to the development of clinical jaundice,often accompanied by tenderness on palpation of an enlargedliver. The condition is spread by the faeco-oral route and oftenspreads rapidly in closed communities. Liver function tests will becompatible with an acute hepatitis, with elevation of bilirubin andtransaminases. Diagnosis is confirmed by the antibody titre tohepatitis A. The condition is virtually always self-resolving,although rarely the viral hepatitis can lead to fulminant liverfailure.

Hepatitis B is a more serious than hepatitis A. Although it can also produce an acute self-resolving hepatitis, the virus is often produces long-termliver damage, with the development of liver cirrhosis and primaryliver cancers. Therefore, patients may present acutely withmalaise, anorexia, abdominal pain and clinical jaundice due toactive hepatitis, or at a late stage owing to the complications ofcirrhosis, most commonly ascites or variceal bleeding. Treatmentfor acute hepatitis is supportive. In patients with cirrhosis, treatmentis initially dictated by the specific complication at presentationIn established cirrhosis, liver transplantation may be considered if viral eradication or suppression can be achieved with anti-viral agents (e.g. lamivudine).

Hepatitis C has become one of the most common causes ofchronic liver disease worldwide .Transmission is often related back to blood transfusion, and routine screening of blood for HCV has only recently been introduced in many countries.

Ascending cholangitisAscending bacterial infection of the biliary tract is usually associatedwith obstruction and presents with clinical jaundice, rigorsand a tender hepatomegaly. The diagnosis is confirmed by thefinding of dilated bile ducts on ultrasound, an obstructive pictureof liver function tests and the isolation of an organism from theblood on culture. The condition is a medical emergency, anddelay in appropriate treatment results in organ failure secondaryto septicaemia. Once the diagnosis has been confirmed, thepatient should be commenced on a first-line antibiotic (e.g. third generationcephalosporin) and rehydrated, and arrangementsshould be made for endoscopic or percutaneous transhepaticdrainage of the biliary tree. Biliary stone disease is a common predisposingfactor, and the causative ductal stones may be removedat the time of endoscopic cholangiography by endoscopic sphincterotomy.

Pyogenic liver abscessThe aetiology of a pyogenic liver abscess is unexplained in themajority of patients. It has an increased incidence in the elderly,diabetics and the immunosuppressed, present with anorexia, fevers and malaise, accompanied by right upper quadrant discomfort. The diagnosis is suggested by the finding of amultiloculated cystic mass on ultrasound or CT scan and is confirmed by aspiration for culture and sensitivity.

most common organisms are Streptococcus milleri and Escherichiacoli, but other enteric organisms such as Streptococcus faecalis,Klebsiella and Proteus and mixed growths are common.Treatment is with antibiotics and ultrasound-guided aspiration.First-line antibiotics to be used are a penicillin, aminoglycosideand metronidazole or a cephalosporin and metronidazole.

Amoebic liver abscessEntamoeba histolytica is endemic in many parts of the world. Itexists in vegetative form outside the body and is spread by thefaeco-oral route. The most common presentation is with dysentery,but it may also present with an amoebic abscess, the commonsites being paracaecal and in the liver. The amoebic cyst isingested and develops into the trophozoite form in the colon, andthen passes through the bowel wall and to the liver via the portalblood. Diagnosis is by isolation of the parasite from the liverlesion or the stool and confirming its nature by microscopy. Oftenpatients with clinical signs of an amoebic abscess will be treatedempirically with metronidazole (750 mg t.d.s. for 5–10 days) .

Hydatid Liver CystEchinococcosis (hydatid disease) is a zoonosis caused by the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus . Humans are accidental intermediate hosts, whereas animals can be both intermediate hosts and definitive hosts. The two main types of hydatid disease are caused by E. granulosus and E. multilocularis. The former is commonly seen in the Mediterranean, South America, the Middle East, and is the most common type of hydatid disease in humans.In humans, 50–75% of the cysts occur in the liver, 25% are located in the lungs, and 5–10% distribute along the arterial system.

The life cycle of E. granulosus has two hosts. The definitive host is usually a dog . The adult worm of the parasite lives in the proximal small bowel of the definitive host attached to the mucosa. Eggs are released into the host's intestine and excreted in the feces. Sheep are the most common intermediate host, and these animals ingest the ovum while grazing. The ovum loses the protective layer and is digested in the duodenum. The released hexacanth embryo passes through the intestinal wall into the portal circulation and develops into cysts within the liver. The definitive host eats the viscera of the intermediate host and the cycle is completed .

PathologyThe typical hydatid cyst has a three-layer wall surrounding a fluid cavity. The outer layer is the pericyst, a thin, indistinct fibrous tissue layer representing an adventitial reaction to the parasitic infection. The pericyst acts as a mechanical support for the hydatid cyst . As the cyst grows, bile ducts and blood vessels stretch and become incorporated within this structure, which explains the biliary and hemorrhagic complications of cyst growth . Over time, the pericyst calcifies. The intermediate layer of the cyst itself is the ectocyst or laminated membrane and is bluish-white, gelatinous.The inner layer or endocyst is the germinal membrane, responsible for the production of clear hydatid fluid, the ectocyst, scoleces, and daughter cysts. The endocyst is 10–25 m thick and attached tenuously to the laminated membrane. The function of the inner layer is important for the nutrition of the cyst. The inner layer also has a proliferative function producing the ectocyst and scoleces(daughter cyst). In uncomplicated cysts, the cyst cavity is filled with sterile, colorless, antigenic fluid containing salt, enzymes, proteins, and toxic substances.

The clinical features of hydatid liver disease depend on the site, size, stage of development, whether the cyst is alive or dead, and whether the cyst is infected or not. Pain in the RUQ or epigastrium is the most common symptom, whereas hepatomegaly and a palpable mass are the most common signs. Nonspecific fever, fatigue, nausea, and dyspepsia may also be present . Approximately one-third of patients will have eosinophilia, and only 20% will present with jaundice and hyperbilirubinemia

Serological test e.g’ The Casoni test are no longer used due to their low sensitivities. Determination of specific antigens and immune complexes of the cyst with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) give a positive result in more than 90% of patients. The arc 5 antibody test involves precipitation during immunoelectrophoresis of the blood of patients with the antigen. Positivity for this test is 90%.RadiologyChest radiographs may show an elevated diaphragm and concentric calcifications in the cyst wall, but are of limited value. Ultrasound and CT are considered the first choice for imaging . Classic findings of hydatid cysts are calcified thick walls, often with daughter cysts. Ultrasound defines the internal structure, number, and location of the cysts and the presence of complications.

Computed tomography gives similar information to ultrasound, but more specific information about the location and depth of the cyst within the liver. Daughter cysts , and the volume of the cyst can be estimated. CT is imperative for operative management, especially when a laparoscopic approach is utilized.MRI provides structural details of the hydatid cyst, but adds little more than ultrasound or CT, and is more expensive. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may show communication between the cysts and bile ducts and can be used to drain the biliary tree before surgery.

TreatmentMost hydatid cysts are asymptomatic on presentation. Medical, surgical, and percutaneous approaches may be part of the treatment . Small cysts (<4 cm) located deep in the parenchyma of the liver, if uncomplicated, can be managed conservatively. AntihelminthicsMedical therapy for echinococcosis is limited to the benzimidazoles (mebendazole and albendazole) and used alone is only 30% successful. Mebendazole is poorly absorbed and is inactivated by the liver. Albendazole is thus the drug of choice for medical therapy. Given for at least 3 months preoperatively, albendazole reduces the recurrence rate when cyst spillage, partial cyst removal, or biliary rupture has occurred. Duration of therapy in these instances is at least 1 month.

The PAIR technique (percutaneous aspiration, injection and re-aspiration) has also been combined with albendazole therapy with 70% success rates and a low rate of recurrence

The surgical options range from liver resection or localexcision of the cysts to de-roofing with evacuation of the contents Contamination of the peritoneal cavity at the time of surgery withactive hydatid daughters should be avoided by continuing drugtherapy with albendazole and adding peroperative praziquantel.This should be combined with packing of the peritoneal cavitywith hypertonic (2 mol l–1) saline-soaked packs and injection2 mol l–1 saline into the cyst before it is opened.

ComplicationsComplications from hydatid cysts are seen in one-third of patients. Most commonly, the cyst ruptures internally or externally, followed by secondary infection, anaphylactic shock, and liver replacement, in order of decreasing frequency.

LIVER TUMOURS Benign liver tumoursHaemangiomasThese are the most common liver lesions, and their reporting has increased with the widespread availability of diagnostic ultrasound. They consist of an abnormal plexus of vessels, and their nature is usually apparent on ultrasound. If diagnostic uncertainty exists, CT scanning with delayed contrast enhancement shows the characteristic appearance of slow contrast enhancement due to small vessel uptake in the haemangioma. Often, haemangiomas are multiple. Lesions found incidentally require confirmation of their nature and no further treatment.

Hepatic adenoma These are rare benign liver tumours. Imaging by CT demonstratesa well-circumscribed and vascular solid tumour. These tumoursare thought to have malignant potential, and resection is thereforethe treatment of choice. An associationwith sex hormones (including the oral contraceptive pill) is wellrecognised,

Focal nodular hyperplasiaThis is an unusual benign condition of unknown aetiology in whichthere is a focal overgrowth of functioning liver tissue supported byfibrous stroma. Patients are usually middle-aged females.

Hepatocellular carcinomaPrimary liver cancer (HCC) is one of the world’s most commoncancers, and its incidence is expected to rise rapidly over the nextdecade due to the association with chronic liver disease, particularlyHBV and HCV. Many patients known to have chronic liverdisease are now being screened for the development of HCC byserial ultrasound scans of the liver or serum measurements ofalphafetoprotein (AFP). Patients often present in middle age,either because of the symptoms of chronic liver disease (malaise,weakness, jaundice, ascites, variceal bleed, encephalopathy) orwith the anorexia and weight loss of an advanced cancer.

The treatment options include resection of the tumour andliver transplantation Which option is most appropriate for an individual patient depends on the stage of the underlying liver disease, the size and site of the tumour, the availability of organ transplantation and the management of the immunosuppressed patient.