The vermiform appendix

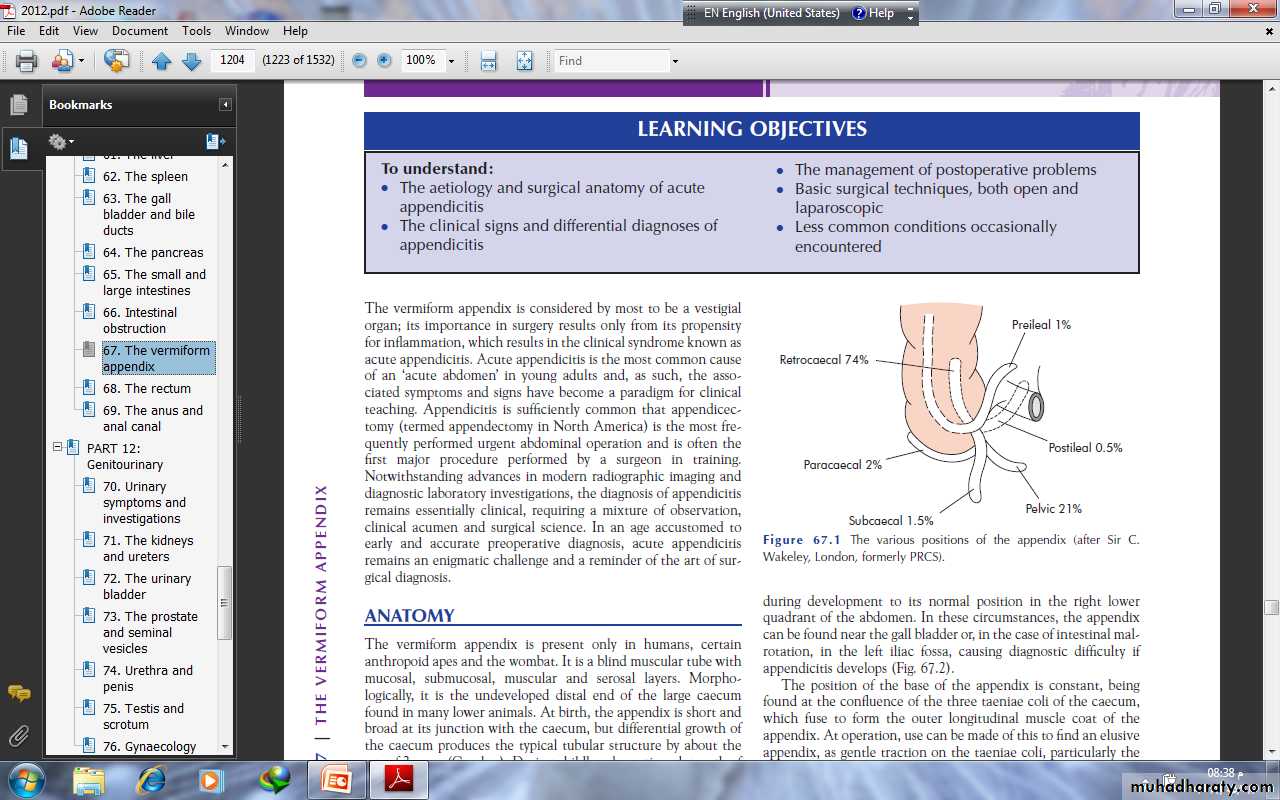

The vermiform appendix is considered by most to be a vestigialorgan; its importance in surgery results only from its propensityfor inflammation, which results in the clinical syndrome known asacute appendicitis. Acute appendicitis is the most common causeof an ‘acute abdomen’ in young adults.It is a blind muscular tube with mucosal, submucosal, muscular and serosal layers. Morphologically,it is the undeveloped distal end of the large caecumfound in many lower animals. At birth, the appendix is short andbroad at its junction with the caecum. The position of the base of the appendix is constant, beingfound at the confluence of the three taeniae coli of the caecum,which fuse to form the outer longitudinal muscle coat of theappendix.

The mesentery of the appendix or mesoappendix arises fromthe lower surface of the mesentery or the terminal ileum. Sometimes, as much as the distalone-third of the appendix is bereft of mesoappendix. Especially inchildhood, the mesoappendix is so transparent that the contained blood vessels can be seen. The appendicular artery, a branch of the lower division of the ileocolic artery, passes behind the terminal ileum to enter the mesoappendix a short distance from the base of the appendix

The appendix varies considerably in length and circumference.The average length is between 7.5 and 10 cm.mucous membrane lined by columnar cell intestinal mucosa ofcolonic type . Crypts are present but are not numerous.In the base of the crypts lie argentaffin cells (Kulchitsky cells),which may give rise to carcinoid tumours

While no discernible change in immunefunction results from appendicectomy, the prominence of lymphatic tissue in the appendix of young adults seems to be important in the aetiology of appendicitis

ACUTE APPENDICITISWhile there are isolated reports of perityphlitis (fatal inflammation of the caecal region) from the late 1500s, recognition of acute appendicitis as a clinical entity is attributed to Reginald Fitz, who presented a paper to the first meeting of the Association of American Physicians in 1886 entitled ‘Perforating inflammation of the vermiform appendix’. Soon afterwards, Charles McBurney described the clinical manifestations of acute appendicitis including the point of maximum tenderness in the right iliac fossa that now bears his name.

The incidence of appendicitis seems to have risen greatly inthe first half of this century, particularly in Europe, America andAustralasia, with up to 16% of the populationappendicectomy is 8.6% and 6.7% among males and females Acute appendicitis is relatively rare in infants, and becomesincreasingly common in childhood and early adult life, reaching apeak incidence in the teens and early 20s respectively.

AetiologyThere is no unigue hypothesis regarding the aetiology of acuteappendicitis. Decreased dietary fibre and increased consumptionof refined carbohydrates may be important.

A mixed growth of aerobic and anaerobic organisms is usual. Theinitiating event causing bacterial proliferation is controversial.Obstruction of the appendix lumen has been widely held to beimportant, and some form of luminal obstruction, either by afaecolith or a stricture, is found in the majority of cases.

Obstruction of the appendiceal orifice by tumour, particularlycarcinoma of the caecum, is an occasional cause of acuteappendicitis in middle-aged and elderly patients. Intestinal parasites, particularly Oxyuris vermicularis (pinworm), can proliferate in the appendix and occlude the lumen

PathologyObstruction of the appendiceal lumen seems to be essential forthe development of appendiceal gangrene and perforation. Yet, in many cases of early appendicitis, the appendix lumen is patentdespite the presence of mucosal inflammation and lymphoid hyperplasia Resolution may occur at this point either spontaneouslyor in response to antibiotic therapy.

distension of the appendix may cause venousobstruction and ischaemia of the appendix wall. Withischaemia, bacterial invasion occurs through the muscularis propria and submucosa, producing acute appendicitis .Finally, ischaemic necrosis of the appendix wall produces gangrenous appendicitis, with free bacterial contamination of the peritoneal cavity. Alternatively, the greater omentum and loops of small bowel become adherent to the inflamed appendix, walling off the spread of peritoneal contamination, and resulting in a phlegmonous mass or paracaecal abscess

Peritonitis occurs as a result of free migrationof bacteria through an ischaemic appendicular wall, the frankperforation of a gangrenous appendix or the delayed perforationof an appendix abscess. Factors that promote this process include extremes of age, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus and faecolith obstruction of the appendix lumen, a free-lying pelvic appendix and previous abdominal surgery that limits the ability of the greater omentum to wall off the spread of peritoneal contamination.

Clinical diagnosisHistoryThe classical features of acute appendicitis begin with poorlylocalised colicky abdominal pain. This is due to mid-gut visceraldiscomfort in response to appendiceal inflammation and obstruction. The pain is frequently first noticed in the peri-umbilical region . Central abdominal pain is associated with anorexia, nausea and usually one or two episodes of vomiting . A family history is also useful as up to one-third of childrenwith appendicitis have a first-degree relative with a similarhistory..

With progressive inflammation of the appendix, the parietal peritoneum in the right iliac fossa becomes irritated, producing more intense, constant and localised somatic pain that begins to predominate. patients often report this as an abdominal pain that has shifted and changed in character.

Atypical presentations include pain that ispredominantly somatic or visceral and poorly localised. Atypicalpain is more common in the elderly, in whom localisation to theright iliac fossa is unusual. An inflamed appendix in the pelvismay never produce somatic pain involving the anterior abdominal wall, but may instead cause suprapubic discomfort and tenesmus.

During the first 6 hours, there is rarely any alteration intemperature or pulse rate. After that time, slight pyrexia (37.2–37.7°C) with a corresponding increase in the pulse rate to 80 or90 is usual

SignsThe diagnosis of appendicitis rests more on thorough clinicalexamination of the abdomen than on any aspect of the history or laboratory investigation

Clinical signs in appendicitis■ Pyrexia■ Localised tenderness in the right iliac fossa■ Muscle guarding■ Rebound tenderness

Signs to elicit in appendicitis■ Pointing sign■ Rovsing’s sign■ Psoas sign■ Obturator sign

Special features, according to position of theappendixRetrocaecalRigidity is often absent, and even application of deep pressuremay fail to elicit tenderness (silent appendix), the reason beingthat the caecum, distended with gas, prevents the pressure Psoas spasm, due to theinflamed appendix being in contact with that muscle, may be sufficient.

PelvicOccasionally, early diarrhoea results from an inflamed appendixbeing in contact with the rectum. When the appendix liesentirely within the pelvis, there is usually complete absence ofabdominal rigidity, and often tenderness over McBurney’s point is also lacking .a rectal examination reveals tenderness in the rectovesical pouch or the pouch of Douglas, especially on the right side

PregnancyAppendicitis is the most common extrauterine acute abdominalcondition in pregnancy, Diagnosis is complicated by delay in presentation as early non-specific symptoms are often attributed to the pregnancy.Obstetric teaching has been that the caecum and appendix areprogressively pushed to the right upper quadrant of the abdomen Fetal loss occurs in 3–5% of cases, increasing to 20% if perforation is found at operation.

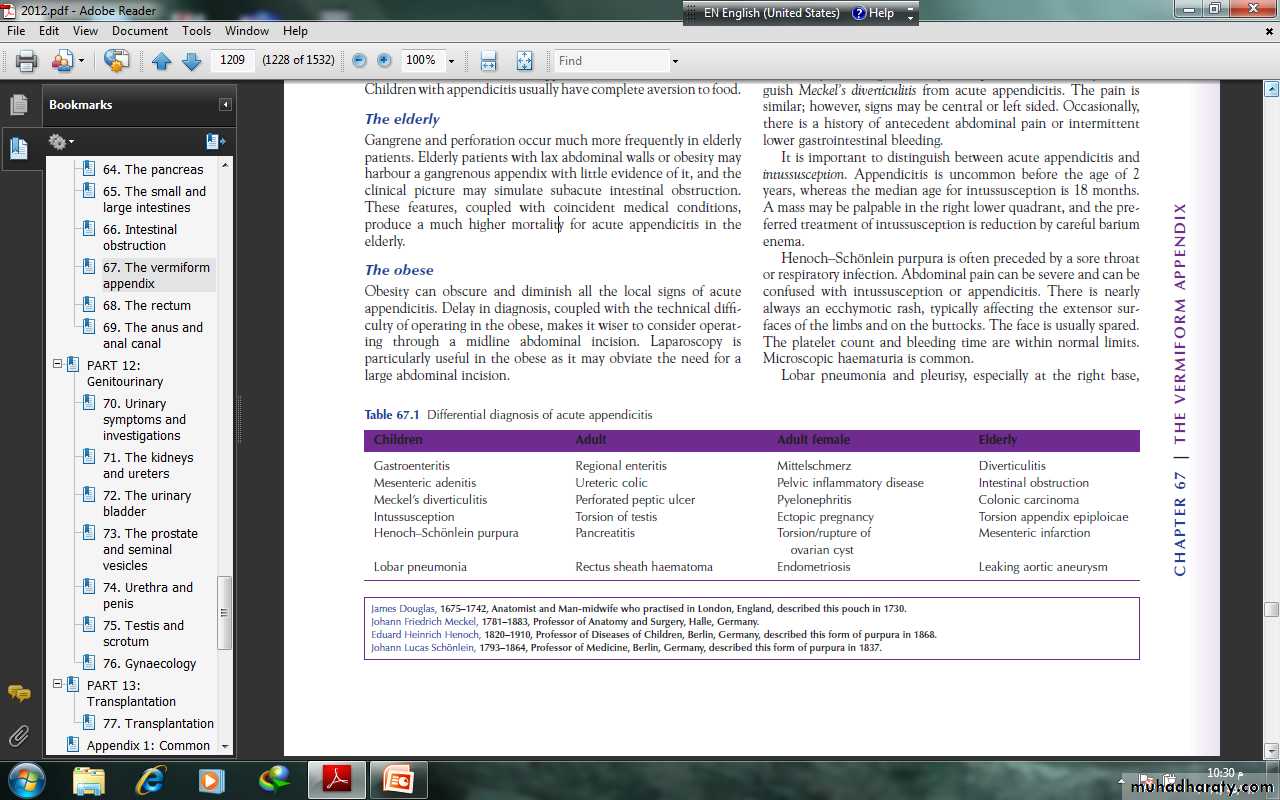

Differential diagnosisAlthough acute appendicitis is the most common abdominal surgical emergency, the diagnosis can be extremely difficult at times

ChildrenThe diseases most commonly mistaken for acute appendicitis areacute gastroenteritis and mesenteric lymphadenitis. In mesentericlymphadenitis, the pain is colicky in nature and cervical lymphnodes may be enlarged. It may be impossible to clinically distinguishMeckel’s diverticulitis from acute appendicitis. The pain issimilar; however, signs may be central or left sided. Occasionally,there is a history of antecedent abdominal pain or intermittentlower gastrointestinal bleeding.It is important to distinguish between acute appendicitis andintussusception. Appendicitis is uncommon before the age of 2years, whereas the median age for intussusception is 18 months.A mass may be palpable in the right lower quadrant.

Henoch–Schonlein purpura is often preceded by a sore throator respiratory infection. There is nearlyalways an ecchymotic rash, typically affecting the extensor surfaces of the limbs and on the buttocks.The platelet count and bleeding time are within normal limits.Microscopic haematuria is common.Lobar pneumonia and pleurisy, especially at the right base

AdultsTerminal ileitis in its acute form may be indistinguishable fromacute appendicitis unless a doughy mass of inflamed ileum can be felt. An antecedent history of abdominal cramping, weight loss and diarrhoea suggests regional ileitis rather than appendicitis.The ileitis may be non-specific, due to Crohn’s disease or Yersiniainfection. Yersinia enterocolitica causes inflammation of the terminal ileum, appendix and caecum with mesenteric adenopathy. If suspected, serum antibody titres are diagnostic, and treatment with intravenous tetracycline is appropriate.

Ureteric colic does not commonly cause diagnostic difficulty,as the character and radiation of pain differs from that of appendicitis.Urinalysis should always be performed, and the presenceof red cells should prompt a supine abdominal radiograph. Renalultrasound or intravenous urogram is diagnostic.Right-sided acute pyelonephritis is accompanied and oftenpreceded by increased frequency of micturition. It may causedifficulty in diagnosis, especially in women. The leading featuresare tenderness confined to the loin, fever (temperature 39°C) and possibly rigors and pyuria.

In perforated peptic ulcer, the duodenal contents pass alongthe paracolic gutter to the right iliac fossa. As a rule, there is ahistory of dyspepsia and a very sudden onset of pain that starts in the epigastrium and passes down the right paracolic gutter. Inappendicitis, the pain starts classically in the umbilical region.Rigidity and tenderness in the right iliac fossa are present in bothconditions but, in perforated duodenal ulcer, the rigidity is usually greater in the right hypochondrium. An erect chest radiograph will show gas under the diaphragm in 70% of patients.

Testicular torsion in a teenage or young adult male is easilymissed. Pain can be referred to the right iliac fossa, and shynesson the part of the patient may lead the unwary to suspect appendicitis unless the scrotum is examined in all cases.Acute pancreatitis should be considered in the differentialdiagnosis of all adults suspected of having acute appendicitis and, when appropriate, should be excluded by serum or urinaryamylase measurement.

Rectus sheath haematoma is a relatively rare but easily misseddifferential diagnosis. It usually presents with acute pain andlocalised tenderness in the right iliac fossa, often after an episode of strenuous physical exercise. Localised pain without gastrointestinal upset is the rule. Occasionally, in an elderly patient, particularlyone taking anticoagulant therapy, a rectus sheathhaematoma may present as a mass and tenderness in the rightiliac fossa after minor trauma.

Adult female It is in women of childbearing age that pelvic disease most oftenmimics acute appendicitis. A careful gynaecological historyshould be taken in all women with suspected appendicitis, concentrating on menstrual cycle, vaginal discharge and possiblepregnancy. The most common diagnostic mimics are pelvicinflammatory disease (PID), Mittelschmerz, torsion or haemorrhage of an ovarian cyst and ectopic pregnancy.

Pelvic inflammatory disease Typically, the pain is lower than in appendicitisand is bilateral. A history of vaginal discharge, dysmenorrhoeaand burning pain on micturition is a helpful differentialdiagnostic point. The physical findings include adenexal and cervical tenderness on vaginal examination

MittelschmerzMidcycle rupture of a follicular cyst with bleeding produces lower abdominal and pelvic pain, typically midcycle. Systemic upset is rare, a pregnancy test is negative, and symptoms usually subside within hours.

Torsion/haemorrhage of an ovarian cystThis can prove a difficult differential diagnosis. When suspected,pelvic ultrasound and a gynaecological opinion should be sought. Documented visualisation of the contralateral ovary is an essential medico-legal precaution prior to oophorectomy for any reason

Ectopic pregnancy The pain is severe and continues unabated until operation. Usually, there is a history of a missed menstrual period, and a urinary pregnancy test may be positive.Severe pain is felt when the cervix is moved on vaginal examination.Signs of intraperitoneal bleeding usually become apparent,and the patient should be questioned specifically regarding referredpain in the shoulder. Pelvic ultrasonography should be carried out inall cases in which an ectopic pregnancy is a possible diagnosis.

ElderlySigmoid diverticulitisIn some patients with a long sigmoid loop, the colon lies to the right of the midline, and it may be impossible to differentiate between diverticulitis and appendicitis. Abdominal CT scanning is particularly useful in this setting and should be considered in the management of all patients over the age of 60 years.

Intestinal obstructionThe diagnosis of intestinal obstruction is usually clear.Carcinoma of the caecumWhen obstructed or locally perforated, carcinoma of the caecummay mimic or cause obstructive appendicitis in adults. A historyof altered bowel habit or unexplained anaemia should raise suspicion. A mass may be palpable and barium enema diagnostic

TreatmentThe treatment for acute appendicitis is appendicectomy. There isa perception that urgent operation is essential to prevent theincreased morbidity and mortality of peritonitis.

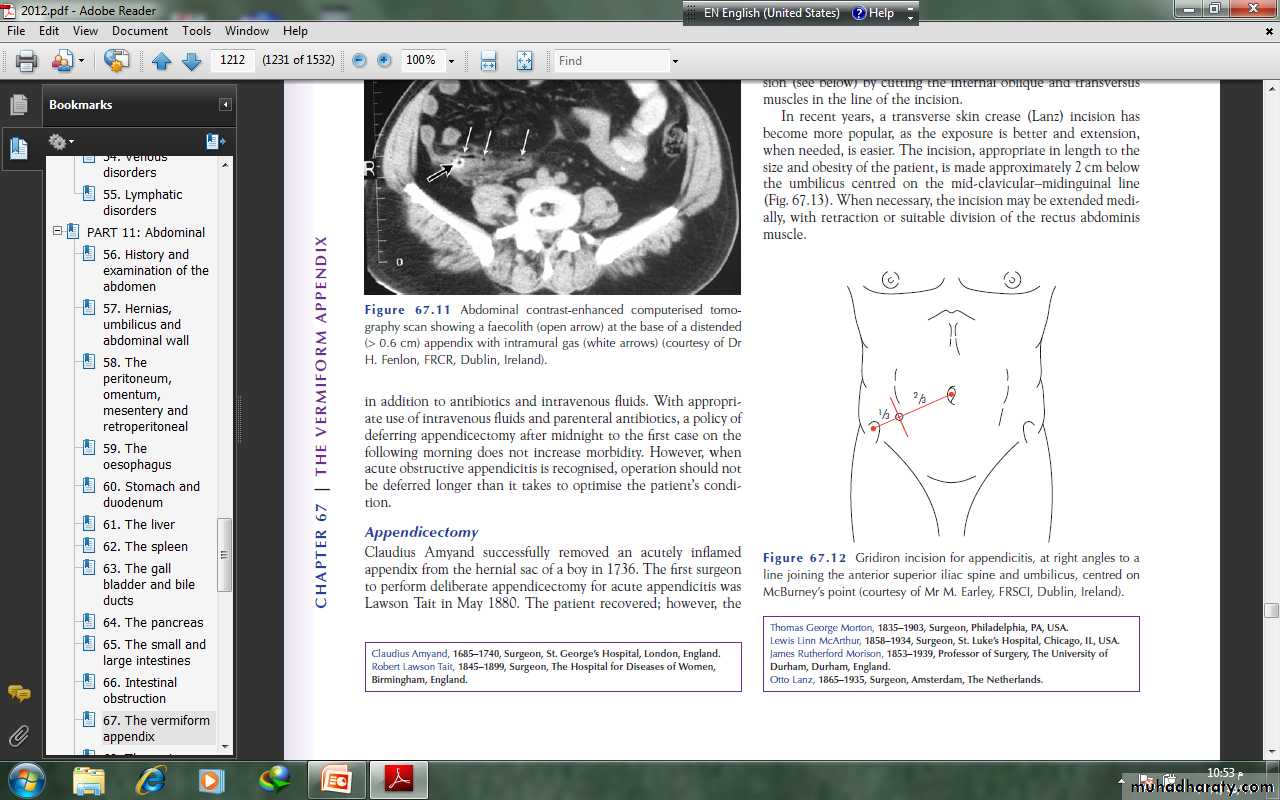

With appropriateuse of intravenous fluids and parenteral antibiotics, a policy ofdeferring appendicectomy after midnight to the first case on thefollowing morning does not increase morbidity. However, whenacute obstructive appendicitis is recognised, operation should not be deferred longer than it takes to optimise the patient’s condition.

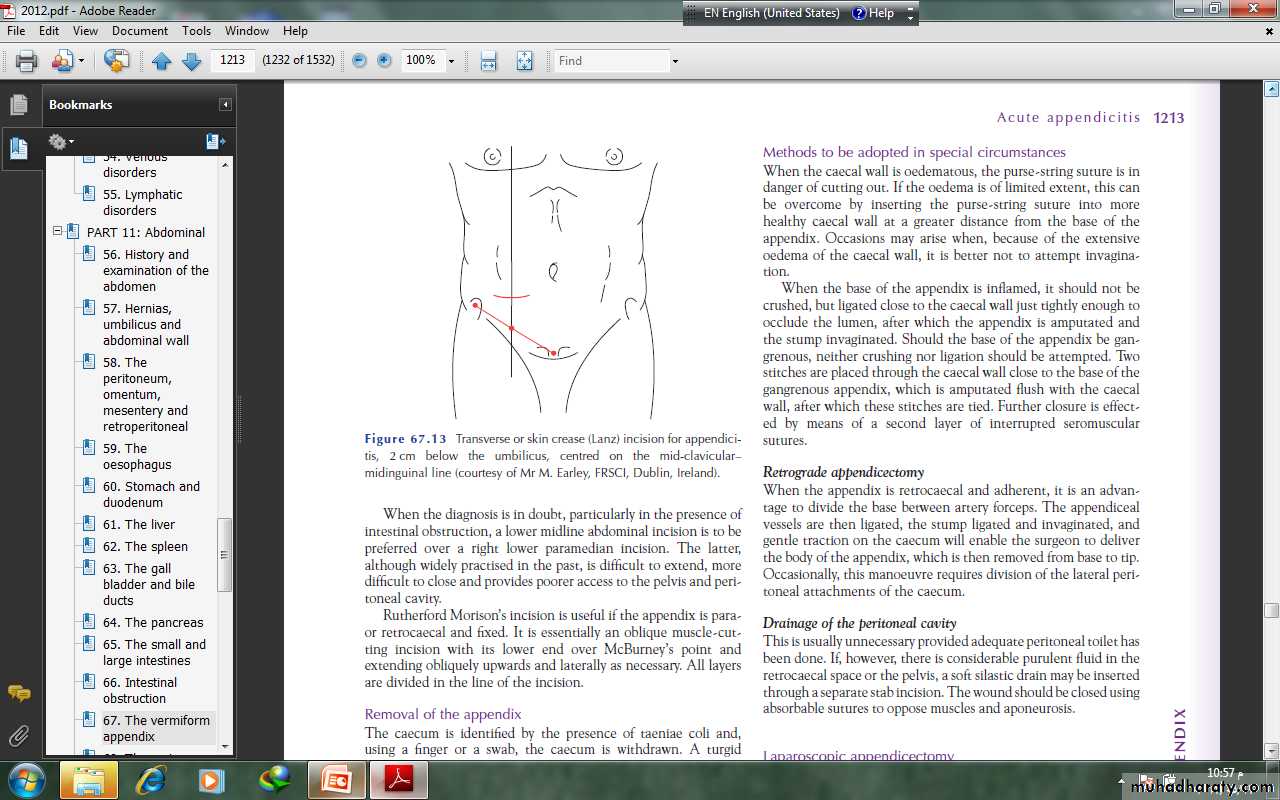

AppendicectomyClaudius Amyand successfully removed an acutely inflamedappendix from the hernial sac of a boy in 1736. The first surgeonto perform deliberate appendicectomy for acute appendicitis was Lawson Tait in May 1880. The patient recovered

Appendicectomy should be performed under general anaesthetic with the patient supine on the operating table

Patients who undergo laparoscopic appendicectomy are likelyto have less postoperative pain and to be discharged from hospital and return to activities of daily living sooner than those who have undergone open appendicectomy. While the incidence of postoperative wound infection is lower after the laparoscopictechnique

Appendix abscessFailure of resolution of an appendix mass or continued spikingpyrexia usually indicates that there is pus within the phlegmonousappendix mass. Ultrasound or abdominal CT scan mayidentify an area suitable for the insertion of a percutaneous drain.Should this prove unsuccessful, laparotomy though a midlineincision is indicated

Management of an appendix massIf an appendix mass is present and the condition of the patient issatisfactory, the standard treatment is the conservativeOchsner–Sherren regimen .inadvertent surgery is difficult and may be dangerous. It may beimpossible to find the appendix and, occasionally, a faecal fistulamay form. For these reasons, it is wise to observe a non-operative programme but to be prepared to operate should clinical deterioration occur.

Careful recording of the patient’s condition and the extent ofthe mass should be made and the abdomen regularly re-examined.It is helpful to mark the limits of the mass on the abdominalwall using a skin pencil. A contrast-enhanced CTexamination of the abdomen should be performed and antibiotictherapy instigated. An abscess, if present, should be drainedradiologically. Temperature and pulse rate should be recorded 4-hourly and a fluid balance record maintaine

Clinical deteriorationor evidence of peritonitis is an indication for earlylaparotomy. Clinical improvement is usually evident within24–48 hours. Failure of the mass to resolve should raise suspicion of a carcinoma or Crohn’s disease. Using this regimen,approximately 90% of cases resolve without incident. The greatmajority of patients will not develop recurrence, and it is nolonger considered advisable to remove the appendix after aninterval of 6–8 weeks.

Clinical deteriorationor evidence of peritonitis is an indication for earlylaparotomy. Clinical improvement is usually evident within24–48 hours. Failure of the mass to resolve should raise suspicion of a carcinoma or Crohn’s disease. Using this regimen,approximately 90% of cases resolve without incident. The greatmajority of patients will not develop recurrence, and it is nolonger considered advisable to remove the appendix after aninterval of 6–8 weeks.

Postoperative complicationsPostoperative complications following appendicectomy are relatively uncommonWound infectionWound infection is the most common postoperative complication, occurring in 5–10% of all patients. This usually presents with pain and erythema of the wound on the fourth or fifth postoperative day, often soon after hospital discharge. Treatment is by wound drainage and antibiotics .

Intra-abdominal abscessIntra-abdominal abscess has become a relatively rare complicationafter appendicectomy with the use of peroperative antibiotics.Postoperative spiking fever, malaise and anorexiadeveloping 5–7 days after operation suggest an intraperitonealcollection. Interloop, paracolic, pelvic and subphrenic sitesshould be considered. Abdominal ultrasonography and CT scanning greatly facilitate diagnosis and allow percutaneous drainage.Laparotomy should be considered in patients suspected of having intra-abdominal sepsis but in whom imaging fails to show a collection, particularly those with continuing ileus.

IleusA period of adynamic ileus is to be expected after appendicectomy,and this may last a number of days following removal of agangrenous appendix. Ileus persisting for more than 4 or 5 days,particularly in the presence of a fever, is indicative of continuingintra-abdominal sepsis and should prompt further investigation.RespiratoryIn the absence of concurrent pulmonary disease, respiratorycomplications are rare following appendicectomy. Adequatepostoperative analgesia and physiotherapy, when appropriate,reduce the incidence.Venous thrombosis and embolismThese conditions are rare after appendicectomy, except inthe elderly and in women taking the oral contraceptive pill.Appropriate prophylactic measures should be taken in suchcases.

Portal pyaemia (pylephlebitis)This is a rare but very serious complication of gangrenousappendicitis associated with high fever, rigors and jaundice. Itis caused by septicaemia in the portal venous system and leadsto the development of intrahepatic abscesses .Faecal fistulaLeakage from the appendicular stump occurs rarely, but mayfollow if the encircling stitch has been put in too deeply orif the caecal wall was involved by oedema or inflammation.Occasionally, a fistula may result following appendicectomy inCrohn’s disease. Conservative management with low-residueenteral nutrition will usually result in closure.Adhesive intestinal obstructionThis is the most common late complication of appendicectomy.At operation, a single band adhesion is often found to beresponsible. Occasionally, chronic pain in the right iliac fossais attributed to adhesion formation after appendicectomy. Insuch cases, laparoscopy is of value in confirming the presence ofadhesions and allowing division.

Recurrent acute appendicitisAppendicitis is notoriously recurrent. It is not uncommonfor patients to attribute such attacks to ‘biliousness’ or dyspepsia.The attacks vary in intensity and may occur everyfew months, and the majority of cases ultimately culminatein severe acute appendicitis. If a careful history is takenfrom patients with acute appendicitis, many remember havinghad milder but similar attacks of pain. The appendix inthese cases shows fibrosis indicative of previous inflammation.

Neoplasms of the appendixCarcinoid tumoursCarcinoid tumours (synonym: argentaffinoma) arise in argentaffin tissue (Kulchitsky cells of the crypts of Lieberkühn)and are most common in the vermiform appendix. Carcinoidtumour is found once in every 300–400 appendices subjectedto histological examination and is ten times more commonthan any other neoplasm of the appendix. In many instances,the appendix had been removed because of symptoms of subacute or recurrent appendicitis.

Appendicectomy has been shown to be sufficient treatment,unless the caecal wall is involved, the tumour is 2 cmor more in size or involved lymph nodes are found, when righthemicolectomy is indicated.