NEOPLASIA

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States that after the cardiovascular diseases. Even more agonizing than the associated mortality is the emotional and physical suffering caused by neoplasms, the only hope for controlling cancer lies in learning more about its pathogenesis, and great steps have been made in understanding the molecular basis of cancer .So that we will talk about :

the nature of benign and malignant neoplasms .

the molecular basis of neoplastic transformation.

The host response to tumors .

clinical features of neoplasia and new advances in diagnosis of neoplasm .

Before we discuss the features of cancer cells and the mechanisms of carcinogenesis, it is useful to summarize the fundamental and shared characteristics of cancers:

• Cancer is a genetic disorder caused by DNA mutations. Most pathogenic mutations are either induced by exposure to mutagens or occur spontaneously as part of aging.

• Genetic alterations in cancer cells are heritable, being passed to daughter cells upon cell division.

• Mutations and epigenetic alterations impart to cancer cells a set of properties that are referred to collectively as cancer hallmarks. These properties produce the cellular phenotypes that give the natural history of cancers as well as their response to various therapies.

Basic research has elucidated many of the cellular and molecular abnormalities that give rise to cancer and govern its pernicious behavior. These insights are in turn leading to a revolution in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer .

NOMENCLATURE:

Neoplasia literally means “new growth.” Neoplastic cells are said to be transformed because they continue to replicate without control, malignant tumors are collectively referred to as cancers, derived from the Latin word for “crab”—that is, they adhere to any part , similar to a crab’s behaviorAll neoplasms have two basic components

The “transformed” neoplastic cells (the parenchyma)The supportive stroma.

The latter is composed of non-transformed (non-neoplastic) elements, such as connective tissues and blood vessels.

Classifications of neoplasms are based on their parenchymal components.

BENIGN TUMORS

In general their names end with the suffix “oma”.

Benign mesenchymal tumors are named after their tissue of origin + “oma”

Examples

Leiomyoma

Lipoma

Chondroma,

Schwannoma, etc.

Benign epithelial tumors are named after their tissue of origin, sometimes combined with architecture + “oma”.

Examples

Adenomas are tumors arising from glandular tissue and usually form glandular patterns

Cystadenomas as above but with cystic components

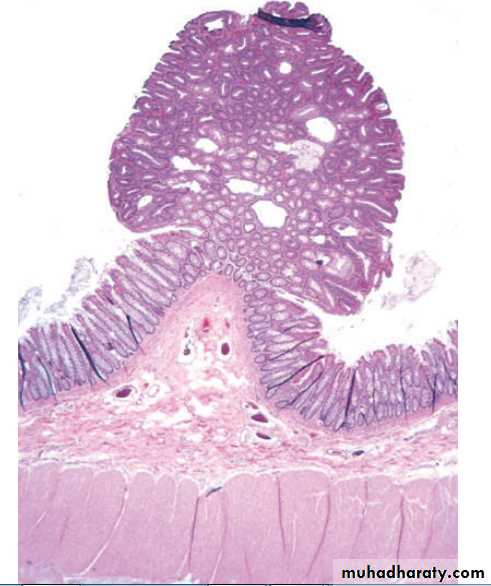

Papillary cystadenoma as above but with papillary (warty or finger-like projections)

Papillomas characterized by the production of finger like projections.

MALIGNAT TUMORS

These are generally called cancers.Their nomenclature is based on their appearance (the morphology of their parenchymal cells) and the presumed tissue of origin.

They’re broadly divided into two categories

Carcinomas arising from epithelial cellsExamples include

Squamous cell carcinomas,

Adenocarcinoma,

small cell undifferentiated carcinomas, etc.

Sarcomas arising from or differentiating towards mesenchymal tissues

Examples includeOsteosarcomas

Leiomyosarcomas,

Rhabdomyosarcomas.

Some tumors have more than one parechymal cell type, these include

1. Teratomas, which are tumors of germ cell origin, showing differentiation along all the three germ layers (Ectoderm: like skin and its adnexae such as hair follicles and sebaceous glands, Endoderm: like gut epithelia and Mesoderm: like bone, cartilage, muscle, etc), thus a variety of parenchymal cell types may be seen in any one of these neoplasms.Examples include

teratoma of the ovary

teratoma of the testis

Mixed tumors; these differ from teratomas in that they are derived from one germ cell layer, that differentiates into more than one parenchymal cell type.

Examples include

Pleomorphic adenoma of salivary glands

Fibroadenoma of breast

EXCEPTIONS

Exceptions to the above mentioned rules include tumors that are always malignant such asLymphomas (tumors of lymphoid tissue).

melanomas (malignant tumors of melanocytes)

Seminomas and Dysgerminomas (tumors of primitive germ cells) .

CHARACTERISTICS OF BENIGN AND MALIGNANT TUMORS

BENIGN TUMORSMALIGNANT TUMORS

Rate of growth

Slower

Faster

Histological features

Similar to tissue of origin.

Nuclei are normal.

Cells uniform in size and shape.Many differ from tissue of origin.

Enlarged pleomorphic nuclei, hyerchromasia, Prominent nucleoli, Increased mitotic activity, abnormal mitosis. Cellular pleomorphism in size and shape.

Clinical effects

Local pressure effects.

Hormone secretion.

Cured by adequate excision.Local pressure and tissue destructive effects.

Inappropriate hormone secretion.

Not cured by local excision because of metastasis.Paraneoplastic syndromes.

CHARACTERISTICS OF BENIGN AND MALIGNANT NEOPLASMS

There are three fundamental features by which most benign and malignant tumors can be distinguished:differentiation and anaplasia.

local invasion .

and metastasis.

DIFFERENTIATION AND ANAPLASIA

Differentiation is the extent to which tumor cells resemble comparable normal cells of the tissue of origin.

In most benign tumors the constituent cells closely mimic corresponding normal cells.

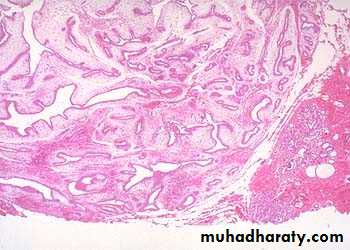

Malignant tumors display a range of differentiations that form the basis of tumor grading.

Lack of differentiation (anaplasia) is the hallmark of malignant cells.

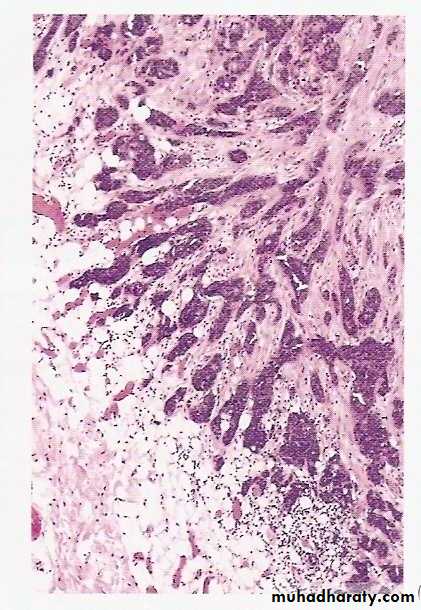

Well differentiated SCC of skin

Pleomorphic malignant tumor (rhabdomyosarcoma)

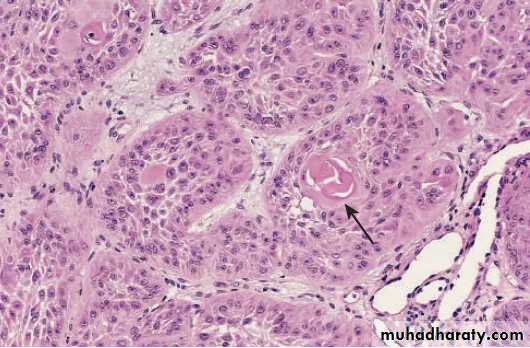

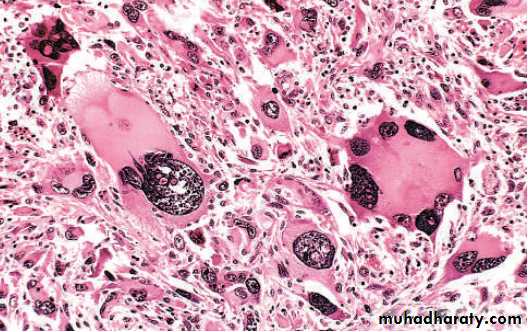

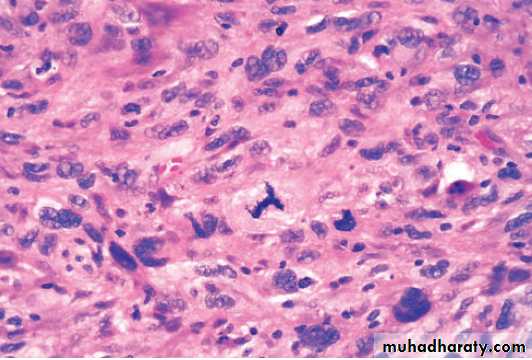

Histopathological features of anaplasia:Cellular and nuclear pleomorphism refers to variation in size and shape of cells and their nuclei.

Hyperchromatism refers to dark staining of nuclei due to abnormally increased chromatin (nucleic acids contents), a reflection of aneuploidy.

Increased nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio (N/C) reaching nearly 1:1 (instead of the normal 1:4-6).

Abundant mitoses reflecting increased proliferative activity

Abnormal mitoses, e.g., tripolar spindles (normally mitosis is bipolar).

Tumor giant cells containing a single giant polypoid nucleus or multiple nuclei.

Prominent nucleoli

Cytoplasmic basophilia reflecting active protein synthesis.

Loss of orientation and disarray of tissue architecture (loss of polarity).

High-power detailed view of anaplastic tumor cells shows cellular and nuclear variation in size and shape. The prominent cell in the center field has an abnormal tripolar spindle.

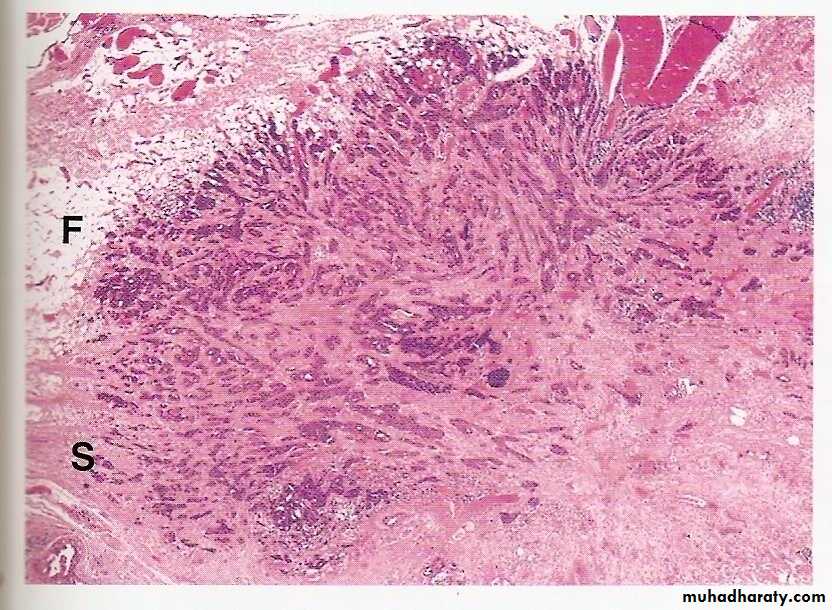

LOCAL INVASION

Most benign tumors grow as cohesive expansile masses that develop a rim of condensed connective tissue or “capsule” at the periphery . They don’t penetrate the capsule or the surrounding normal tissues. The line of cleavage between the capsule and the surrounding normal tissues facilitates surgical enucleation.Malignant tumors are invasive (infiltrative), they invade and destroy normal surrounding tissues. They usually lack a well-defined capsule or line of cleavage, thus, their enucleation is impossible, and their surgical removal requires removal of a considerable margin of healthy apparently uninvolved tissue.

METASTASIS

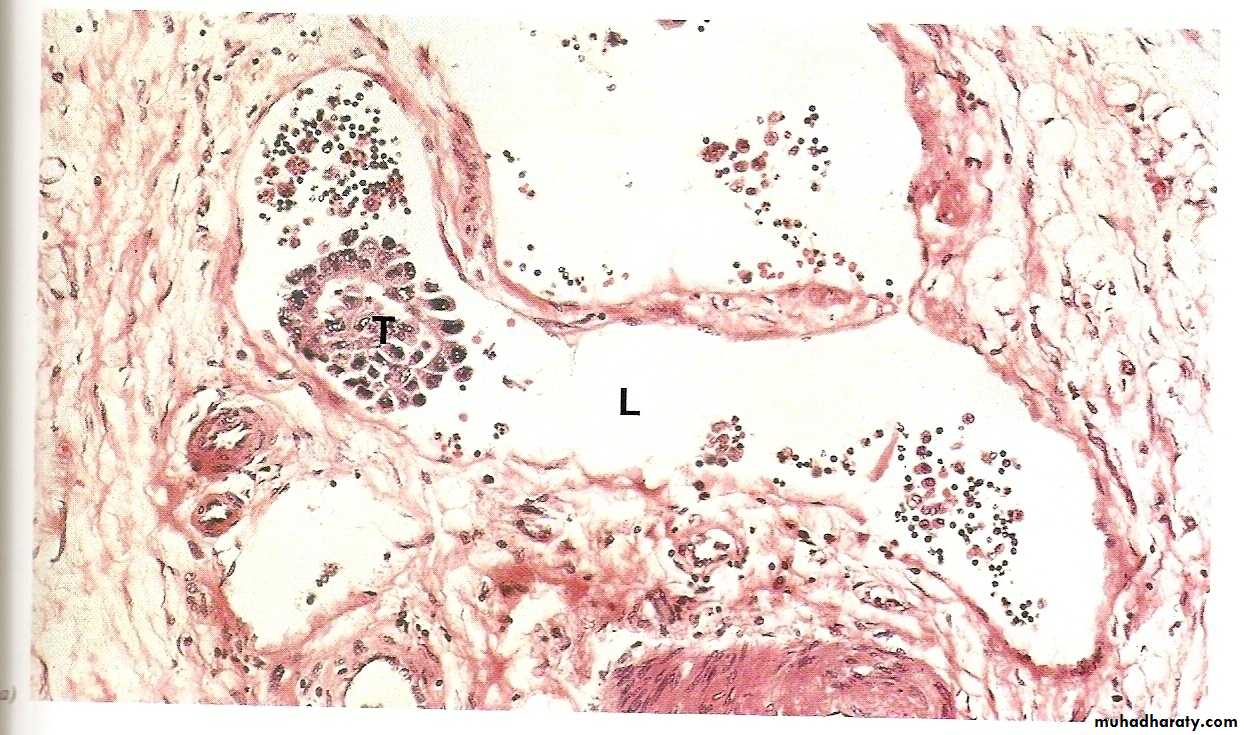

This process involves invasion of blood vessels, lymphatics and body cavities by the malignant tumor, followed by the transport and growth of secondary tumor cell masses that are discontinuous with the primary tumor. These are called secondaries.Metastasis is the absolute criterion of malignancy.

Routes of tumor spread and metastasis

Local spread this occurs by invasion into the adjacent tissues.

Invasion of lymphatics (lymphatic spread). This is followed by spread of the tumor to regional lymph nodes and ultimately to other sites in the body. It is common in the initial spread of carcinomas. Not all enlarged lymph nodes located at the sites of drainage of a malignancy means necessarily a metastasis. This is because immune responses to tumor antigens can result in nodal enlargement too. The latter is through the development of lymphoid hyperplasia.

Invasion of blood vessels (hematogenous spread). This is typical of all sarcomas, but is also the favored route for certain carcinomas (e.g., renal cell carcinoma). Because of their thinner walls, veins are more readily and thus more frequently invaded than arteries. Lungs and liver are the commonest site of hematogenous spread because they receive the systemic and portal venous blood respectively. Other major sites are the bones and brain.