Complications following traumatic injuries to primary teeth may appear

shortly after the injury (e.g., infection of the PDL or dark discoloration of the

crown) or after several months (e.g., yellow discoloration of the crown and

external root resorption).

Pulpitis

The pulp's initial response to trauma is pulpitis. Capillaries in the tooth

become congested, Teeth with reversible pulpitis may be tender to percussion

if the PDL is inflamed (e.g., following a luxation injury). Pulpitis may be

totally reversible if the condition causing it is addressed, or it may progress to

an irreversible state with necrosis of the pulp.

Infection of the Periodontal Ligament

Infection of the PDL becomes possible when detachment of the gingival fibers

from the tooth in a luxation injury allows invasion of microorganisms from the

oral cavity along the root to infect the PDL. Loss of alveolar bone support can

be seen on a periapical radiograph . This diminishes the healing potential of

the supporting tissues. Subsequently, increased tooth mobility accompanied by

exudation of pus from the gingival crevice will require extraction of the

injured tooth.

Pulp Necrosis and Infection

Two main mechanisms can explain how the pulp of injured primary teeth

becomes necrotic: (1) infection of the pulp in cases of untreated crown fracture

with pulp exposure, and (2) interrupted blood supply to the pulp through the

apex in cases of luxation injury leading to ischemia. Periapical radiolucencies

indicative of a granuloma or cyst are frequently evident radiographically in

necrotic anterior teeth.

Coronal Discoloration

As a result of trauma, the capillaries in the pulp occasionally hemorrhage,

leaving blood pigments deposited in the dentinal tubules. In mild cases, the

blood is resorbed and very little discoloration occurs, or that which is present

becomes lighter in several weeks. In more severe cases, the discoloration

persists for the life of the tooth .

From a diagnostic standpoint, discoloration of primary teeth does not

necessarily mean that the tooth is nonvital, particularly when the discoloration

occurs 1 or 2 days after the injury.

Pink discoloration that is observed shortly after the injury may represent

intrapulpal hemorrhage.

Yellow discoloration of primary incisors can be seen when the dentin is thick

and the pulp chamber narrower than usual. This condition is termed pulp canal

obliteration

Dark discoloration of primary teeth is the most controversial posttraumatic

complication in terms of the significance of the change in tooth color. The

term “dark” refers to a variety of shades, including black, gray, brown.

When the pulp becomes necrotic or when pulpal hemorrhage occurs, red blood

cells lyse and release hemoglobin. Hemoglobin and its derivatives, such as

hematin molecules that contain iron ions, invade the dentin tubules and stain

the tooth dark. If the pulp remains vital and eliminates the pigments, the dark

discoloration may fade with subsequent restoration of the original color. If the

pulp loses its vitality and cannot eliminate the iron-containing molecules, the

tooth may remain discolored.

Inflammatory Resorption

Inflammatory resorption can occur either on the external root surface or

internally in the pulp chamber or canal .It occurs subsequent to luxation

injuries and is related to a necrotic pulp and an inflamed PDL.

Internal Resorption

The predentin, an unmineralized layer of organic material, covers the inner

aspect of the dentin and protects it against access of osteoclasts. When the pulp

becomes inflamed, as in cases of traumatic injury, the odontoblastic layer may

lose its integrity and expose the dentin to odontoclastic activity, which is then

seen on radiographs as radiolucent expansion of the pulp space. Eventually

this process reaches the outer surface of the root, causing root perforation.

External Resorption

The cementoblast layer and the precementum serve as a shield protecting the

root from involvement in the perpetual remodeling process of the surrounding

bone. In nontraumatized primary teeth, external root resorption is part of the

physiologic process of replacing the primary dentition with permanent teeth. In

primary incisors sustaining traumatic injuries, external root resorption may

appear as an accelerated unfavorable pathologic reaction.

Pulp Canal Obliteration

Pulp canal obliteration is the result of intensified activity of the odontoblasts

that results in accelerated dentin apposition. Gradually, the pulp space narrows

to a state in which it cannot be seen on a radiograph. PCO is a common finding

in primary incisors following traumatic injuries and is often associated with

yellow coronal discoloration

Replacement Resorption

Replacement resorption, also known as ankylosis, results after irreversible

injury to the PDL. Alveolar bone directly contacts and fuses with the root

surface. As the alveolar bone undergoes normal physiologic osteoclastic and

osteoblastic activity, the root is resorbed and replaced with bone). Ankylosis

occurs more often in intruded primary teeth, and they eventually become

infraoccluded

Injuries to the permanent successor tooth can be expected in 12-69% of

primary tooth trauma and 19-68% of jaw fractures. Intrusive luxation causes

most disturbances. Most damage to the permanent tooth bud occurs under 3

years of age during its developmental stage. However, the type and severity of

disturbance are closely related to the age at the time of injury. Changes in the

mineralization and morphology of the crown of the permanent incisor are most

common, but later injuries can cause radicular anomalies. Injuries to

developing teeth can be classified as follows:

1. White or yellow-brown hypomineralization of enamel.

2. Crown dilaceration.

3. Odontoma-like malformation.

4. Root duplication.

5. Vestibular or lateral root angulation and dilacerations.

6. Partial or complete arrest of root formation.

7. Sequestration of permanent tooth-germs.

8. Disturbance in eruption: Eruption disturbances may involve delay because

of thickening of connective tissue over a permanent tooth-germ, ectopic

eruption due to lack of eruptive guidance, and impaction in teeth with

malformations of crown or root.

The term dilaceration describes an abrupt deviation of the long axis of the

crown or root portion of the tooth. This deviation results from the traumatic

displacement of hard tissue, which has already been formed, relative to

developing soft tissue.

The term angulation describes a curvature of the root resulting from a gradual

change in the direction of root development, without evidence of abrupt

displacement of the tooth-germ during odon-togenesis. This may be vestibular

(i.e. labiopalatal) or lateral (i.e. mesiodistal).

Evaluation of the full extent of complications following injuries must await

complete eruption of all permanent teeth involved. However, most serious

sequelae (disturbances in tooth morphology) can usually be diagnosed

radiographically within the first year post-trauma.

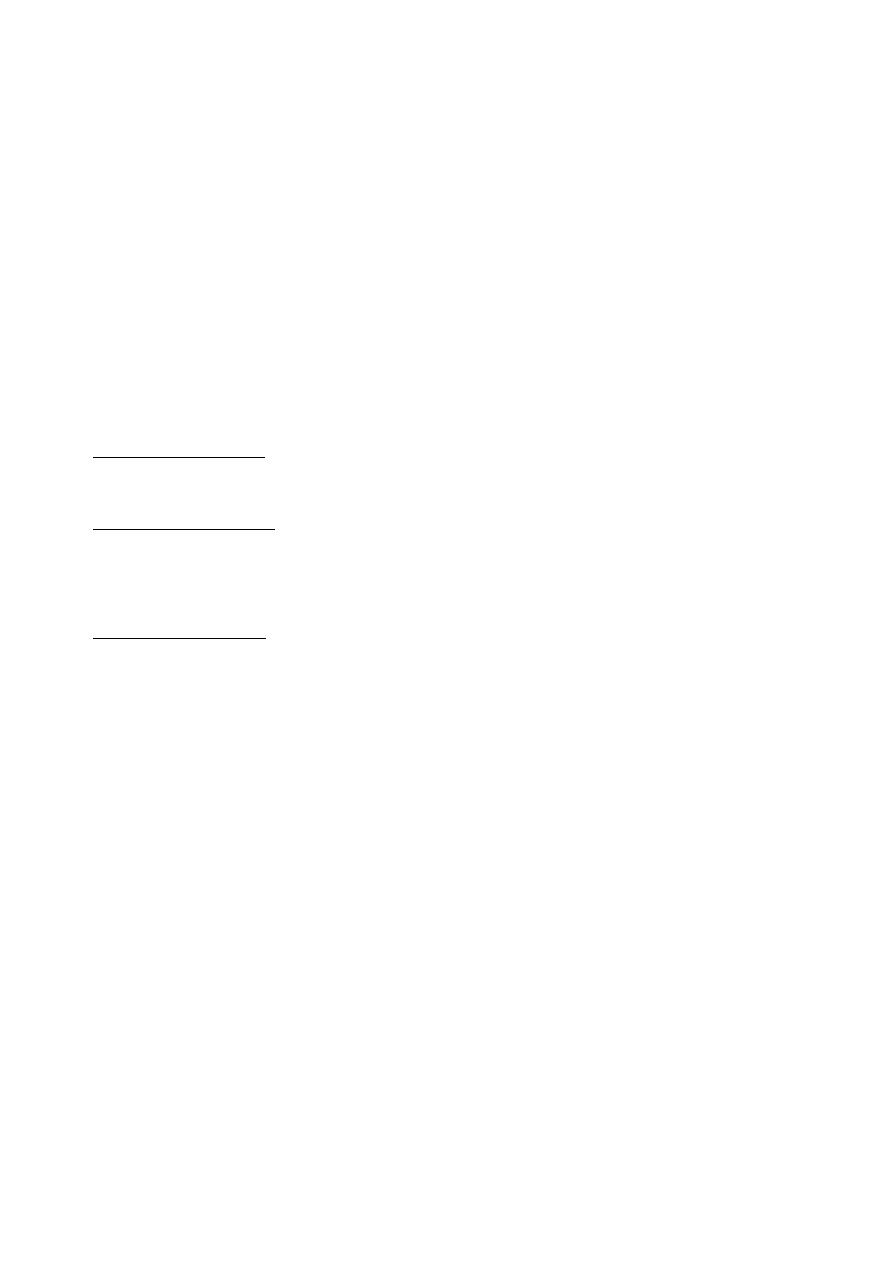

(a) Investigation of delayed eruption of the permanent upper central incisors

revealed (b) an intruded upper left primary central incisor on radiograph. (c)

Following removal of the retained primary incisor, the permanent successor

erupted spontaneously with a white hypoplastic spot on the labial surface.

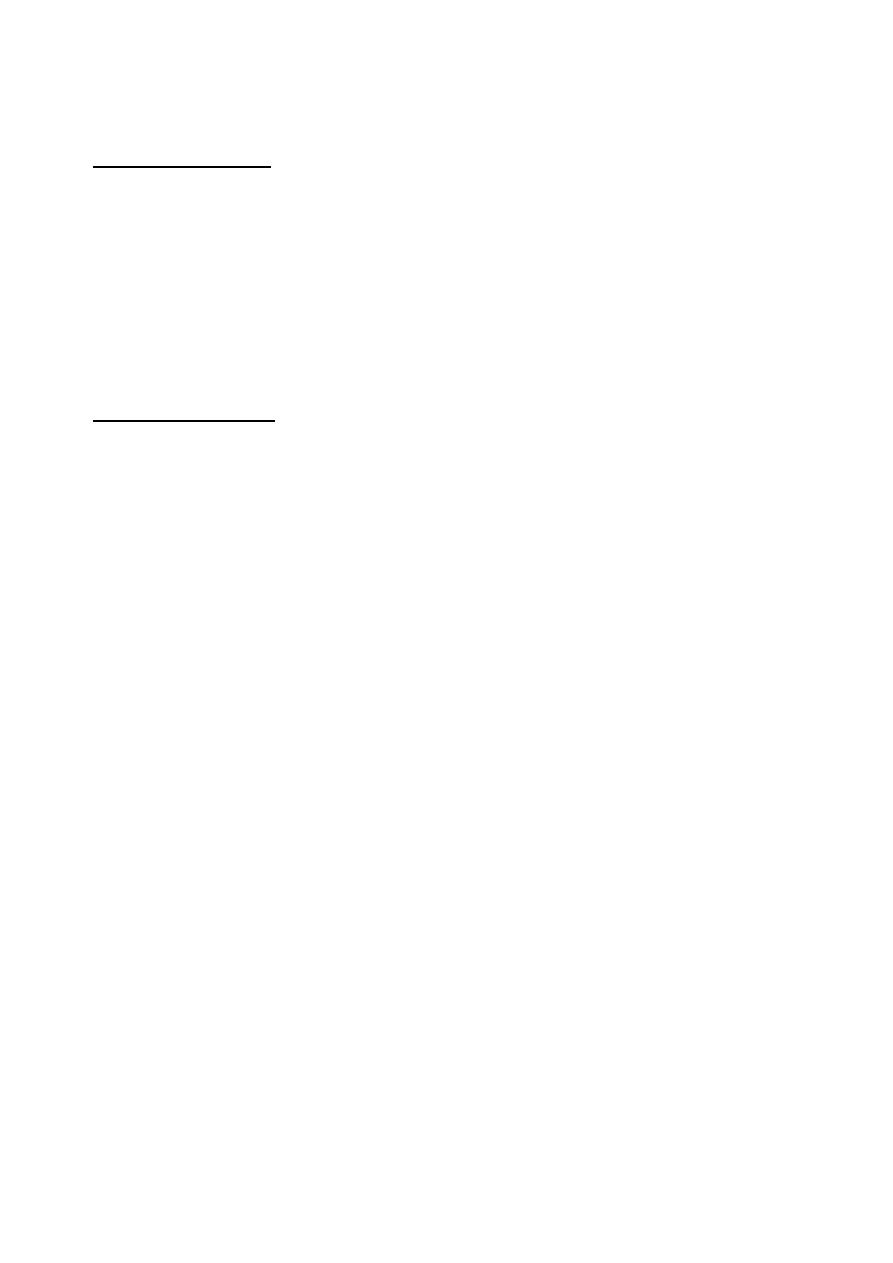

Brown hypoplastic area on the lower left permanent central incisor

Treatment of injuries to the permanent dentition

Yellow-brown hypomineralization of enamel with or without hypoplasia

1. Acid–pumice micro–abrasion.

2. Composite resin restoration: localized, veneer, or crown.

3. Porcelain restoration: veneer or crown . Conservative approaches are

preferred whenever possible.

Crown dilaceration

1. Surgical exposure + orthodontic realignment.

2. Removal of dilacerated part of crown.

3. Temporary crown until root formation complete.

4. Semi-permanent or permanent restoration.

Vestibular root angulation

Combined surgical and orthodontic realignment.

Trauma cases require follow-up to identify any complications and institute the

correct treatment. In the review period the following schedule is a guide: 1

week; 1, 3, 6, and 12 months; then annually for 4–5 years.

Infraction is defined as an incomplete fracture (crack) of the enamel without

loss of tooth structure. Clinical examination reveals normal gross anatomic and

radiographic appearance: however, upon closer examination, craze lines are

apparent in the enamel, especially with transillumination. A periapical

radiograph of the involved area is taken to rule out root fracture and injuries to

the supporting tooth structure. Pulp sensibility testing is recommended in adult

teeth to monitor pulpal changes, however, results in primary teeth may be

unreliable. Test results may be negative initially indicating transient pulpal

damage.

These incomplete fractures without loss of tooth substance and without proper

illumination are easily overlooked. Review is necessary, as above, as the

energy of the blow may have been transmitted to the periodontal tissues or the

pulp.

In some cases, minor enamel fractures can be smoothed with fine disks. Larger

fractures should be restored using an acid-etch/composite resin technique.

1. The primary issue in managing fractures that expose dentin is to prevent

bacterial irritants from reaching the pulp. Standard care in the past called for

covering exposed dentin with calcium hydroxide (CaOH) or glass ionomer

cement to seal out oral flora. Recent research indicates that sealing exposed

dentin with a bonding agent enables the unexposed pulp to form reparative

dentin. Some clinicians are thus advocating simultaneous acid etching of dentin

and enamel followed by dentin and enamel bonding without placement of CaOH

or glass ionomer. However, a recent review of pulp capping with dentin adhesive

systems reported that these systems are not indicated owing to increased

inflammatory reactions, delay in pulp healing, and failure of dentin bridge

formation. Its recommends covering the deepest portion of dentin fractures with

glass ionomer cement, followed by a dentin-bonding agent . The tooth can then

be restored with an acid-etch/composite resin technique .If adequate time is not

available to restore the tooth completely, an interim covering of resin material (a

resin “patch”) can temporize the tooth until a final restoration can be placed.

Some dentists routinely place such a partial restoration to ensure an appropriate

post-treatment evaluation when the patient returns for the final restoration. This

is a reasonable strategy, provided that care is taken to ensure an adequate seal.

2. Reattachment of crown fragment. Few long-term studies have been reported

and the longevity of this type of restoration is uncertain. In addition, there is a

tendency for the distal fragment to become opaque or require further

restorative intervention in the form of a veneer or full-coverage crown . If the

fracture line through dentine is not very close to the pulp, the fragment can be

reattached immediately. However, if it runs close to the pulp, it is advisable to

place a suitably protected calcium hydroxide dressing over the exposed

dentine for at least a month while storing the fragment in saline, which should

be renewed weekly.

Technique

1. Check the fit of the fragment and the vitality of the tooth.

2. Clean fragment and tooth with pumice-water slurry.

3. Isolate the tooth with rubber dam.

4. Attach fragment to a piece of sticky wax to facilitate handling.

5. Etch enamel for 30 seconds on both fracture surfaces and extend for 2mm

from fracture line on tooth and fragment. Wash for 15 seconds and dry for 15

seconds.

6. Apply bonding agent ± dentine primer according to the manufacturer’s

instructions and light cure for 10 seconds.

7. Place appropriate shade of composite resin over both surfaces and position

fragment. Remove gross excess and cure for 60 seconds labially and palatally.

8. Remove any excess composite resin with sandpaper discs.

9. Remove a 1mm gutter of enamel on each side of the fracture line both

labially and palatally to a depth of 0.5mm using a small round or pear-shaped

bur. The finishing line should be irregular in outline.

10. Etch the newly prepared enamel, wash, dry, apply composite, cure, and

finish.

Management of crown fractures that expose the pulp is particularly

challenging .Pertinent clinical findings that dictate treatment include the

following:

1Vitality of the exposed pulp

2Time elapsed since the exposure

3Degree of root maturation of the fractured tooth

4Restorability of the fractured crown

The objective of treatment in managing these injuries is to preserve a vital pulp in

the entire tooth. It is not always possible to maintain vital tissue throughout the

tooth. Three treatment alternatives are available, based on the clinical findings just

noted:

1. Direct pulp cap

2. Pulpotomy

3. Pulpectomy

The direct pulp cap is only indicated in small exposures that can be treated within

a few hours of the injury. The chances for pulp healing decrease if the tissue is

inflamed, has formed a clot, or is contaminated with foreign materials..

A rubber dam is applied, and the tooth is gently cleaned with water. Commercially

available CaOH paste or mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA)

is applied directly to the

pulp tissue and to surrounding dentin. It is essential that a restoration be placed that

is capable of thoroughly sealing the exposure to prevent further contamination by

oral bacteria. As in the management of dentin fractures, it is acceptable to use an

acid-etch/composite resin system for an initial restoration. A calcific bridge

stimulated by the capping material should be evident radiographically in 2 to 3

months.

In fractures exposing pulps of immature permanent teeth with incomplete root

development, a direct cap is no longer the treatment of choice. Failure in these cases

leads to total pulpal necrosis and a fragile, immature root with thin dentinal walls.

Thus the preferred treatment in pulp exposures of immature permanent teeth is

pulpotomy.

Vital pulp therapy: pulpotomy

In pulpotomy a portion of exposed vital pulp is removed to preserve the radicular

vitality and allow completion of apical root development (apexogenesis) and further

deposition of dentine on the walls of the root. This procedure is the treatment of

choice following trauma where the pulp has been exposed to the mouth for more

than 24 hours. The amount of pulp that is removed depends on the time since

exposure, which will also determine the depth of contamination of the pulp.

Attempts must be made to remove only the pulp that is deemed to be contaminated.

If the patient presents within 24–48 hours of the incident, it is safe to assume that

the contaminated zone is no more than 2-4mm around the exposure site and only

the pulp in the immediate vicinity of the exposure is removed, in a procedure also

termed partial pulpotomy (Cvek’s technique). For more extensive exposures all

coronal pulp can be removed down to the cervical constriction of the tooth .