The complications of peptic ulceration

The common complications of peptic ulcer areperforation, bleeding and

stenosis.

The complications of peptic ulceration

Perforated peptic ulcerDespite the widespread use of gastric antisecretory agents and eradication therapy, the incidence of perforated peptic ulcer has changed little. Such that perforations now occur most commonly in elderly female patients.

NSAIDs appear to be responsible for most of these perforations.

Clinically the patient, who may have a history of peptic ulceration, develops sudden-onset severe generalized abdominal pain due to the irritant effect of gastric acid on the peritoneum. Although the contents of an acid-producing stomach are relatively low in bacterial load, bacterial peritonitis supervenes over a few hours, usually accompanied by a deterioration in the patient’s condition.

Initially, the patient may be shocked with a tachycardia but a pyrexia is not usually observed until some hours after the event.

The abdomen exhibits a board-like rigidity and the patient is disinclined to move because of the pain. The abdomen does not move with respiration. Patients with this form of presentation need an operation, without which the patient will deteriorate with a septic peritonitis

They may present only with pain in the epigastrium and right iliac fossa as the fluid may track down the right paracolic gutter. Sometimes perforations will seal owing to the inflammatory response and adhesion within

the abdominal cavity, and so the perforation may be self- limiting.

By far the most common site of perforation is the anterior aspect of the duodenum. However, the anterior or incisural gastric ulcer may perforate and, in addition, gastric ulcers may perforate into the lesser sac, which can be particularly difficult to diagnose. These patients may not have obvious peritonitis.

INVESTIGATIONS

An erect plain chest radiograph will reveal free gas under the diaphragm in excess of 50% of cases with perforated peptic ulcer but CT imaging is more accurate . All patients should have serum amylase performed, as distinguishing between peptic ulcer, perforation and pancreatitis can be difficult.

TREATMENT

The initial priorities are resuscitation and analgesia. Analgesia should not be withheld

for fear of removing the signs of an intra-abdominal catastrophe.

Laparotomy is performed, usually through an upper midline incision if the diagnosis

of perforated peptic ulcer can be made with confidence.

Alternatively, laparoscopy may be used. The most important component of the

operation is a thorough peritoneal toilet to remove all of the fluid and food debris.

Gastric ulcers should, if possible, be excised and closed, so that malignancy can be

excluded. Occasionally a patient is seen who has a massive duodenal or gastric perforation such that simple closure is impossible; in these patients a distal gastrostomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction is the procedure of choice.

All patients should be treated with systemic antibiotics in addition to a thorough peritoneal lavage.

Following operation, gastric antisecretory agents should be started immediately.

H. pylori eradication is mandatory.

Perforated peptic ulcers can often be managed by minimally invasive techniques if the expertise is available. The principles of operation are, however, the same; thorough peritoneal toilet is performed and the perforation is closed by intracorporeal suturing.

Whatever technique is used, it is important that the stomach is kept empty postoperatively by nasogastric suction, and that gastric antisecretory agents are commenced to promote healing in the residual ulcer.

However, undoubtedly, there are patients who have small leaks from a perforated peptic ulcer and rela-

tively mild peritoneal contamination, who may be managed with intravenous fluids, nasogastric suction and antibiotics. These patients are in the minority.

A number of factors have been associated with poor outcome after perforated peptic ulcer, including:

● delay in diagnosis (>24 hours);

● medical comorbidities;

● shock;

● increasing age (>75).

Patients who have suffered one perforation may suffer another one. Therefore, they should bemanaged aggressively to ensure that this does not happen.

Lifelong treatment with proton pump inhibitors is a reasonable option especially in those who have to continue with NSAID treatment.

HAEMATEMESIS AND MELAENA

Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage remains a major medical problem .Haemorrhage is strongly associated with NSAID use. Despite improvements in diagnosis and the proliferation in treatment modalities over the last few decades, an in-hospital mortality of 5–10% can be expected.

This rises to 33% when bleeding is first observed in patients who are hospitalised for other reasons.

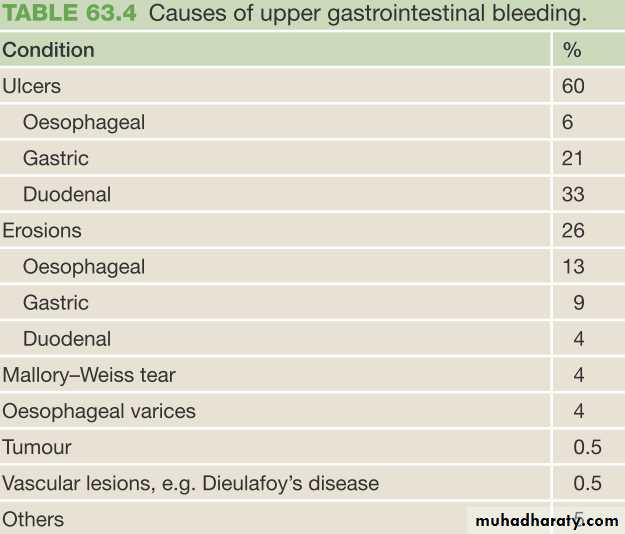

In patients in whom the cause of bleeding can be found, the most common causes are

peptic ulcer, erosions, Mallory–Weiss tear and

bleeding oesophageal varices .

Whatever the cause, the principles of management are

identical.First, the patient should be adequately resuscitated and,

following this, the patient should be investigated urgently to

determine the cause of the bleeding.

Only then should treatment of a definitive nature be instituted.

For any significant gastrointestinal bleed, intravenous

access should be established and, for those with severe

bleeding, central venous pressure monitoring should be set up

and bladder catheterisation performed.

Blood should be cross-matched and the patient transfused as

clinically indicated, usually when >30% of blood volume

has been lost.

As a general rule, most gastrointestinal bleeding will stop, albeit temporarily, but there are sometimes instances when this is not the case.

In these circumstances, resuscitation, diagnosis and treatment should be carried out simultaneously.

For instance, in patients with known oesophageal varices and uncontrollable bleeding, a Sengstaken–Blakemore tube may be inserted before an endoscopy has been carried out. This practice is not to be encouraged, except in extremis.

In some patients, bleeding is secondary to a coagulopathy. The most important current causes of this are liver disease and inadequately controlled warfarin therapy. In these circumstances the coagulopathy should be corrected, if possible, with fresh-frozen plasma or concentrated clotting factors.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy should be carried out by an experienced operator as soon as practicable after the patient has been stabilised.

Bleeding peptic ulcers

In recent years, the population affected has become much older and the bleeding is commonly associated with the ingestion of NSAIDs. Diagnosis can normally be made endoscopically.Medical and minimally interventional treatments

Medical treatment has limited efficacy. All patients are commonly started on either an H 2 -antagonist or a proton pump antagonist, and recent evidence confirms the benefit of proton pump inhibitor administration to prevent rebleeding after endoscopy.

*Therapeutic endoscopy can achieve haemostasis in approximately 70% of cases, with the best evidence supporting a combination of adrenaline injection with heater pobe and/or clips.

Therapeutic endoscopy will probably never be effective in patients who are bleeding from large vessels and with which the majority of the mortality is associated.

*In patients where the source of bleeding cannot be identified or in those who rebleed after endoscopy, angiography with transcatheter embolisation may offer a valuable alternative to surgery in expert centres.

*Surgical treatment criteria for surgery are a patient who

continues to bleed requires surgical treatment.The same applies to a significant rebleed.

The only exception applies in expert centres with 24-hour interventional radiology and experience of angiographic embolisation where attempts may be made to arrest bleeding and avoid surgery.

*Endoscopical finding of Patients with a visible vessel in the ulcer base, a spurting vessel or an ulcer with aclot in the base are statistically likely to require surgical treatment to stop the bleeding.

*Elderly and unfit patients are more likely to die as a result of bleeding than younger patients. Ironically, they should have early surgery.

*A patient who has required more than six units of blood in general needs surgical treatment.

The most common site of bleeding from a peptic ulcer is the duodenum. Following mobilisation, the duodenum, and usually the pylorus, is opened longitudinally as in a pyloroplasty. This allows good access to the ulcer, which is usually found posteriorly or superiorly. Following under-running, it is often possible to close the mucosa over the ulcer. The pyloroplasty is then closed with interrupted sutures in a transverse direction as in the usual fashion.

In a giant ulcer the first part o the duodenum may be destroyed making primary closure impossible. In this circumstance one should proceed to distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction.

The principles of management of bleeding gastric ulcers are essentially the same.

The stomach is opened at an appropriate position anteriorly and the vessel in the ulcer under-run.If the ulcer is not excised then a biopsy of the edge needs to be taken to exclude malignant transformation.

Bearing in mind that most patients nowadays are elderly and unfit, the minimum surgery that stops the bleeding is probably optimal Acid can be inhibited by pharmacological means and appropriate eradication therapy will prevent ulcer recurrence. Definitive acid-lowering surgery is not now required.

Stress ulceration

This commonly occurs in patients with major injury or illness, who have undergone major surgery or who have major comorbidity. Acid inhibition and the nasogastric or oral administration of sucralfate has been shown to reduce the incidence of stress ulceration. Endoscopic means of treating stress ulceration may beineffective and operation may be required. The principles of management are the same as for the chronic ulcer.

Gastric erosions

Erosive gastritis has a variety of causes, especially NSAIDs.Fortunately, most such bleeding settles spontaneously .

In general terms, although there is a diffuse erosive gastritis, there is one (or more) specific lesion that has a significant-sized vessel within it.

This should be dealt with appropriately, preferably endoscopically, but sometimes surgery is necessary.

Mallory–Weiss tear

This is a longitudinal tear at the gastro-oesophageal junction, which is induced by repetitive and strenuous vomiting. Occasionally these lesions continue to bleed and require surgical treatment.Dieulafoy’s disease

This is essentially a gastric arterial venous malformation that has a characteristic histological appearance. Bleeding due to this malformation is one of the most difficult causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding to treat. The lesion itself is covered by normal mucosa and, when not bleeding, it may be invisible. If the lesion can be identified endoscopically there are various means of dealing with it, including injection of sclerosant and endoscopic clips. If it is identified at operation then only a local excision is necessary.Tumours

All of the gastric tumours may present with chronic or acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Bleeding is not normally torrential but can be unremitting.Gastric stromal tumours commonly present with bleeding and have a characteristic appearance, as the mucosa breaks down over the tumour in the gastric wall Whatever the nature, the tumours should be dealt with as appropriate.

Portal hypertension and portal gastropathy

The management of bleeding gastric varices is very challenging. Fortunately, most bleeding from varices is oesophageal and this is much more amenable to sclerotherapy, banding and balloon tamponade.

Gastric varices may also be injected, although this is technically more difficult.

Banding can also be used, again with difficulty.The gastric balloon of the Sengstaken–Blakemore tube can be used to arrest the haemorrhage if it is occurring from the fundus of the stomach or gastrooesophageal junction.

Octreotide is a somatostatin analogue that reduces portal pressure in patients with varices .

TIPSS procedure (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt), can be an extremely useful, although technically demanding procedure.

Aortic enteric fistula

This diagnosis should be considered in any patient with haematemesis and melaena that cannot be otherwise explained.Contrary to expectation, the bleeding from such patients is not always massive, although it can be. The vast majority of patients will have had an aortic graft and, in the absence of this, the diagnosis is unlikely.

A well-performed CT scan will commonly allow the diagnosis to be made with certainty.

should be managed by an expert vascular surgeon as, whether secondary or primary, the morbidity and mortality are high.

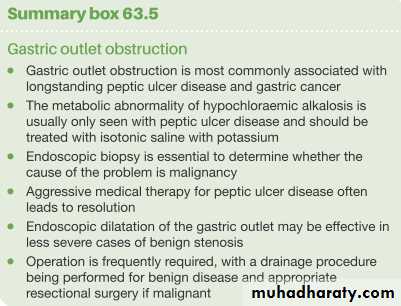

GASTRIC OUTLET OBSTRUCTION

The two common causes of gastric outlet obstruction aregastric cancer and

pyloric stenosis secondary to peptic ulceration.

Previously, the latter was more common. Now, with the decrease in the incidence of peptic ulceration and the advent of potent medical treatments,

gastric outlet obstruction should be considered

malignant until proven otherwise .

Commonly, when the condition is due to

underlying peptic ulcer disease, the stenosis is found

in the first part of the duodenum, the most common

site for a peptic ulcer.

True pyloric stenosis can occur due to fibrosis

around a pyloric channel ulcer.

In some patients the pain may become unremitting and in other cases it may largely disappear.

The vomitus is characteristically unpleasant in nature and is totally lacking in bile.

Very often it is possible to recognise foodstuff taken several days previously.

The patient commonly complains of losing weight, and appears unwell and dehydrated.

When examining the patient, it may be possible to see the distended stomach and a succussion splash may be audible on shaking the patient’s abdomen.

The vomiting of hydrochloric acid results in hypochloraemic alkalosis. Initially the sodium and potassium may be relatively normal. However, as dehydration progresses, more profound metabolic abnormalities arise, partly related to renal dysfunction.

Management

Treating the patient involves correcting the metabolic abnormality and dealing with the mechanical problem.The patient should be rehydrated with intravenous isotonic saline with potassium supplemen. Replacing the sodium chloride and water allows the kidney to correct the acid–base abnormality.

Following rehydration, it may become obvious that the patient is also anaemic, the haemoglobin being spuriously high on presentation.

It is notable that the metabolic abnormalities may be less if the obstruction is due to malignancy, as the acid–base disturbance is less pronounced.

*The stomach should be emptied using a wide-bore gastric tube. A large nasogastric tube may not be sufficiently large to deal with the contents of the stomach, and it may be necessary to pass an orogastric tube and lavage the stomach until it is completely emptied.

*This then allows investigation of the patient with endoscopy and contrast radiology.

Biopsy of the area around the pylorus is essential to exclude malignancy.*The patient should also have a gastric antisecretory agent, initially given intravenously to ensure absorption.

#Early cases may settle with conservative treatment, presumably as the oedema around the ulcer diminishes as the ulcer is healed.

*Traditionally, severe cases are treated surgically, usually with a gastroenterostomy rather than a pyloroplasty.

*Endoscopic treatment with balloon dilatation has been practised and may be most useful in early cases.

Dilating the duodenal stenosis may result in perforation.

*Occasionally duodenal stent insertion will be considered in specialist centres.

Other causes of gastric outlet obstructionAdult pyloric stenosis

This is a rare condition and its relationship to the childhood condition is unclear, although some patients have a long history of problems with gastric emptying. It is commonly treated by pyloroplasty rather than pyloromyotomy.Pyloric mucosal diaphragm

The origin of this rare condition is unknown. It usually does not become apparent until middle life. When found, simple excision of the mucosal diaphragm is all that is required.

GASTRIC POLYPS

Biopsy is essential.• Metaplastic polyp is most common type of gastric. These are associated with H. pylori infection and regress following eradication therapy.

• Inflammatory polyps are also common.

• Fundic gland polyps deserve particular attention. They seem to be associated with the use of proton pump inhibitors and are also found in patients with familial polyposis. None of the above polypoid lesions has proven malignant potential.

• True adenomas have malignant potential and should be removed, but they account for only 10% of polypoid lesions.

• Gastric carcinoids arising from the ECL cells are seen in patients with pernicious anaemia and usually appear as small polyps.

GASTRIC CANCER

Carcinoma of the stomach is a major cause of cancer mortality worldwide. Its prognosis tends to be poor, with cure rates little better than 5–10%, although better results are obtained in Japan, where the disease is common.It rarely disseminates widely before it has involved the lymph nodes .

The only treatment modality able to cure the disease is resectional surgery.

• Incidence

There are marked variations in the incidence of gastric cancer worldwide.In the UK, it is approximately 15/100 000 per year,

in the USA 10/100 000 per year and in

Eastern Europe 40/100 000 per year.

In Japan, the disease is much more common, with an incidence of approximately 70/100 000 per year, and there are small geographical areas in China where the incidence is double that in Japan. • It is a disease of older individuals, with peak incidence in the seventh decade of life.

Adenocarcinoma

Aetiology

• Diet and Drugs

• Helicobacter pylori• Epstein-Barr Virus

• Genetic Factors

• Premalignant Conditions of the Stomach

Polyps

Atrophic Gastritis

Intestinal Metaplasia

Benign Gastric Ulcer

Gastric Remnant Cancer

Ménétrier’s disease

Early Gastric Cancer

• Defined as adenocarcinoma limited to the mucosa and submucosa of the stomach, regardless of lymph node status.• Approximately 10% of patients with early gastric cancer will have lymph node metastases.

• There are several types and subtypes of early gastric cancer

• Approximately 70% of early gastric cancers are well differentiated, and 30% are poorly differentiated.

• The overall cure rate with adequate gastric resection and lymphadenectomy is 95%.

• Small intramucosal lesions can be treated with EMR.Site

SITEThe proximal stomach is now the most common site for gastric cancer in resource-rich western countries.

where distal cancer still predominates, as it does in most of the rest of the world.

Early gastric cancer, Japanese classification

Pathology:Gross Morphology and Histologic Subtypes

There are four gross forms of gastric cancer:

polypoid,

fungating,

ulcerative,and

scirrhous.

In the first two, the bulk of the tumor mass is intraluminal.

Polypoid tumors are not ulcerated; fungating tumors are elevated intraluminally, but also ulcerated.

In the latter two gross subtypes, the bulk of the tumor mass is in the wall of

the stomach.

Ulcerative tumors are self-descriptive;

scirrhous tumors infiltrate the entire thickness of the stomach and cover a very large surface area.

The Borrmann classification

Bormann classification of advanced gastric cancer.This system was developed in 1926; it remains useful today for the description of endoscopic findings.

This system divides gastric carcinoma into five types, depending on the lesion’s

macroscopic appearance .Pathology

The most important prognostic indicators in gastric cancer are both histologic:lymph node involvement and depth of tumor invasion.

Tumor grade (degree of differentiation: well, moderately, or poorly) is also important prognostically.

The most useful clinicopathological classification of gastriccancer is the Lauren classification. In this system there are principally two forms of gastric cancer:

intestinal gastric cancer and

diffuse gastric cancer (often with signet ring cells).

In intestinal gastric cancer, the tumour resembles a carcinoma elsewhere in the tubular gastrointestinal tract and forms polypoid tumours or ulcers. It probably arises in areas of intestinal metaplasia.

Incontrast, diffuse gastric cancer infiltrates deeply into the stomach without forming obvious mass lesions, but spreads widely in the gastric wall.

Not surprisingly, this has a much worse prognosis.

A small proportion of gastric cancers are of mixed morphology.

Spread

1. Direct2. Lymphatic

3. Blood born

4. Trans peritonial

Pathologic Staging

Clinical Manifestationssymptoms

• The most common symptoms are weight loss and decreased food intake due to anorexia and early satiety.

• Abdominal pain (usually not severe and often ignored) also is common.

• Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and bloating.• Acute GI bleeding is somewhat unusual (5%), but chronic occult blood loss is common and manifests as iron deficiency anemia and hemepositive stool.

• Dysphagia is common if the tumor involves the cardia of the stomach.

• Paraneoplastic syndromes such as Trousseau’s syndrome (thrombophlebitis), acanthosis nigricans (hyperpigmentation of the axilla and groin), or peripheral neuropathy are rarely present

Clinical Manifestations

signsPhysical examination typically is normal.

• Other than signs of weight loss, specific physical findings usually indicate incurability.

• A focused examination in a patient in whom gastric cancer is a likely part of the differential diagnosis should include an examination of the neck, chest, abdomen, rectum, and pelvis.

• Cervical, supraclavicular (on the left referred to as Virchow’snode), and axillary lymph nodes may be enlarged,

• There may be a metastatic pleural effusion, or aspiration pneumonitis in a patient with vomiting and/or obstruction.

• An abdominal mass could indicate a large (usually T4 incurable) primary tumor, liver metastases, or carcinomatosis (including Krukenberg’s tumor of the ovary).

• A palpable umbilical nodule (Sister Joseph’s nodule) is pathognomonic of advanced disease, or there may be evidence on exam of malignant ascites.

• Rectal exam may reveal heme-positive stool and hard nodularity extraluminally and anteriorly, indicating so-called drop metastases, or rectal shelf of Bulmer in the pouch of Douglas.

Diagnostic Evaluation:

Distinguishing between peptic ulcer and gastric cancer on clinical grounds alone is usually impossible.Patients over the age of 45 years old who have new-onset dyspepsia, as well as all patients with dyspepsia and alarm symptoms (weight loss, recurrent vomiting, dysphagia, evidence of GI bleeding, or anemia) or with a family history of gastric cancer

should have prompt upper endoscopy and biopsy if a mucosal lesion is noted.