RESPIRATORY TRACT

Prof Dr. Maha ShakirLec 3

CHRONIC BRONCHITIS

Chronic bronchitis is diagnosed on clinical grounds: it is defined by the presence of a persistent productive cough for at least 3 consecutive months in at least 2 consecutive years. It is common among cigarette smokers and urban dwellers in smog-ridden cities; some studies indicate that 20% to 25% of men in the 40- to 65-year-old age group have the disease. In early stages of the disease, the cough raises mucoid sputum, but airflow is not obstructed. Some patients with chronic bronchitis have evidence of hyper responsive airways, with intermittent bronchospasm and wheezing (asthmatic bronchitis), while other bronchitic patients, especially usually with associated emphysema (COPD).Pathogenesis.

The distinctive feature of chronic bronchitis is hypersecretion of mucus, beginning in the large airways. Although the most important cause is cigarette smoking, other air pollutants, may contribute. These environmental irritants induce hypertrophy of mucous glands in the trachea and bronchi as well as an increase in mucin-secreting goblet cells in the epithelial surfaces of smaller bronchi and bronchioles.

These irritants also cause inflammation marked by the infiltration of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes.

In contrast with asthma, eosinophils are not seen in chronic bronchitis.

The airflow obstruction in chronic bronchitis results from:

(1) small airway disease, induced by mucous plugging of the bronchiolar lumen, inflammation, and bronchiolar wall fibrosis, and

(2) coexistent emphysema.

In general, while small airway disease (chronic bronchiolitis) is an important component of early, mild airflow obstruction, chronic bronchitis with significant airflow obstruction almost always is complicated by emphysema.

It is postulated that many of the effects of environmental irritants on respiratory epithelium are mediated by local release of cytokines

Microbial infection often is present but has a secondary role, chiefly by maintaining inflammation and exacerbating symptoms.

Morphology.

Grossly, there may be hyperemia. swelling, and edema of the mucous membranes, frequently accompanied by excessive mucinous mucopurulent secretions layering the epithelial surfaces. Sometimes, heavy casts of secretions and pus fill the bronchi and bronchioles.

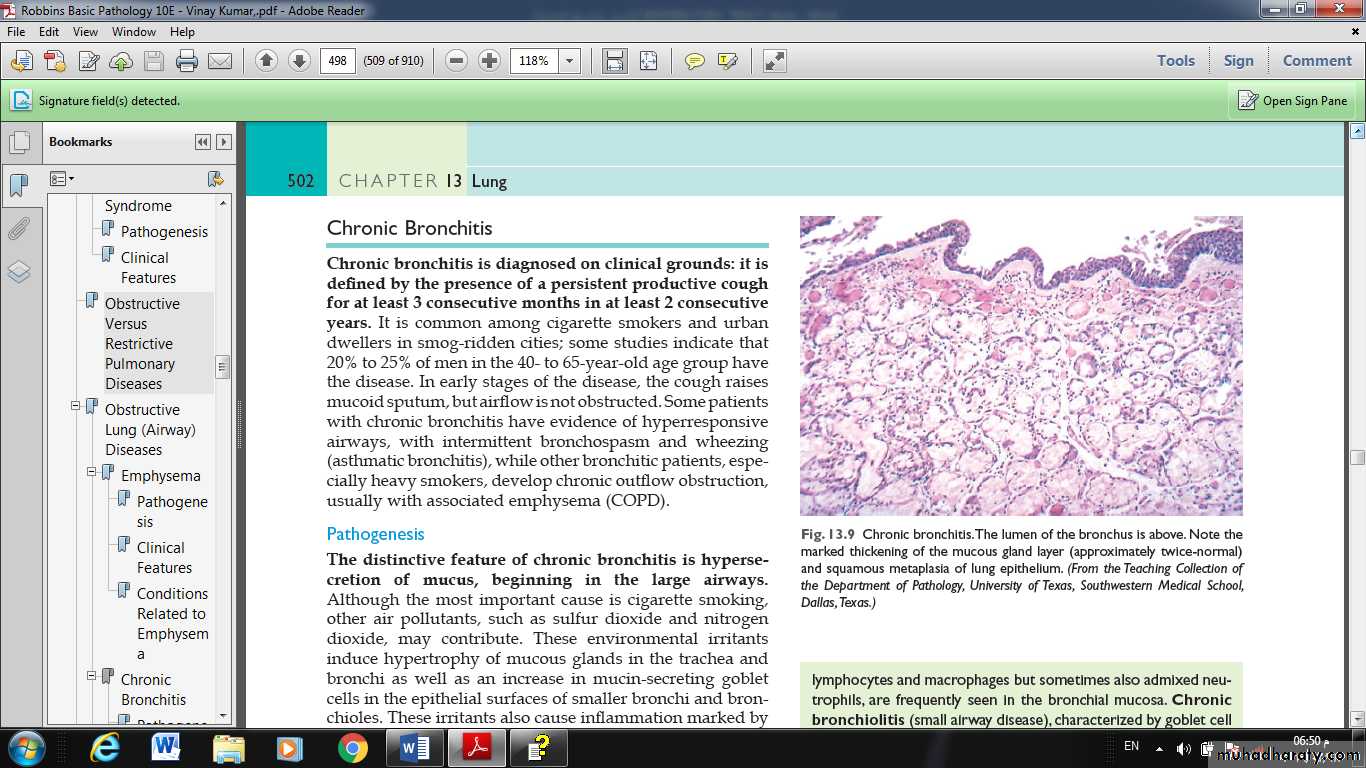

The characteristic histologic features of chronic bronchitis are:

◘ chronic inflammation of the airways (predominantly lymphocytes)

◘ and enlargement of the mucus-secreting glands of the trachea and bronchi.

◘Although the numbers of goblet cells increase slightly, the major increase is in the size of the mucous glands.

◘The bronchial epithelium may show squamous metaplasia and dysplasia.

◘There is marker narrowing of bronchioles caused by goblet cell metaplasia, mucus plugging, inflammation, and fibrosis.

◘ In the most severe cases, there may be obliteration of lumen due to fibrosis (bronchiolitis obliterans).

Fig. Chronic bronchitis. The lumen of the bronchus is above. Note the marked thickening of the mucous gland layer (approximately twice-normal) and squamous metaplasia of lung epithelium.

Clinical Features. The cardinal symptom of chronic bronchitis is a persistent cough productive of sputum. For years, no other respiratory functional impairment is present but eventually, dyspnea on exertion develops. With time, and usually with continued smoking, other elements of COPD may appear, including hypercapnia, hypoxernia, and mild cyanosis.

ASTHMA

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways that causes recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and cough, particularly at night and/or early in the morning. The hallmarks of asthma are:intermittent, reversible airway obstruction;

chronic bronchial inflammation with eosinophils;

bronchial smooth muscle cell hypertrophy and hyperreactivity;

and increased mucus secretion.

Sometimes trivial stimuli are sufficient to trigger attacks in patients, because of airway hyperreactivity.

Many cells play a role in the inflammatory response, in particular eosinophils, mast cells, macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and epithelial cells.

Pathogenesis

Major factors contributing to the development of asthma include genetic predisposition to type I hypersensitivity (atopy), acute and chronic airway inflammation, and bronchial hyper responsiveness to a variety of stimuli.Asthma may be subclassified as atopic (evidence of allergen sensitization) or nonatopic.

In both types, episodes of bronchospasm may be triggered by diverse exposures, such as respiratory infections (especially viral), airborne irritants (e.g., smoke, fumes), cold air, stress, and exercise.

The classic atopic form is associated with classic type I HSR.

Repeated bouts of inflammation lead to structural changes in the bronchial wall that are collectively referred to as airway remodeling. These changes include hypertrophy of bronchial smooth muscle and mucus glands and increased vascularity and deposition of subepithelial

collagen, which may occur as early as several years before initiation of symptoms.

TYPES:

Atopic asthma;

This is the most common type of asthma and is a classic example of type I IgE–mediated hypersensitivity reaction. It usually begins in childhood. A positive family history of atopy and/or asthma is common, and the onset of asthmatic attacks is often preceded by allergic rhinitis, urticaria, or eczema. Attacks may be triggered by allergens in dust, pollen, animal dander, or food, or by infections. A skin test with the offending antigen results in an immediate wheal-and-flare reaction. Atopic asthma also can be diagnosed based on serum radioallergosorbent tests (RASTs) that identify the presence of IgEs that recognize specific allergens.

Nonatopic asthma:

Patients with nonatopic forms of asthma do not have evidence of allergen sensitization, and skin test results usually are negative. A positive family history of asthma is less common. Respiratory infections due to viruses (e.g., rhinovirus, parainfluenza virus) and inhaled air pollutants are common triggers.It is thought that virus-induced inflammation of the respiratory mucosa lowers the threshold of the subepithelial vagal receptors to irritants. Although the connections are not well understood, the ultimate humoral and cellular mediators of airway obstruction (e.g., eosinophils) are common to both atopic and nonatopic variants of asthma, so they are treated in a similar way.

Drug-Induced asthma:

Several pharmacologic agents provoke asthma, aspirin being the most striking example. Patients with aspirin sensitivity present with recurrent rhinitis, nasal polyps, urticaria, and bronchospasm. The precise pathogenesis is unknown but is likely to involve some abnormality in prostaglandin metabolism stemming from inhibition of cyclooxygenaseby aspirin.

Occupational asthma:

Occupational asthma may be triggered by fumes, organic and chemical dusts (wood, cotton, platinum), gases (toluene), and other chemicals. Asthma attacks usually develop after repeated exposure to the inciting antigen(s).

Morphology of asthma;

• Thickening of airway wall• Sub-basement membrane fibrosis

• Increased submucosal vascularity

• An increase in size of the submucosal glands and goblet cell metaplasia of the airway epithelium

• Hypertrophy and/or hyperplasia of the bronchial muscle