RESPIRATORY TRACT

Prof Dr. Maha ShakirLec.4

ASTHMA

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways that causes recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and cough, particularly at night and/or early in the morning. The hallmarks of asthma are:intermittent, reversible airway obstruction;

chronic bronchial inflammation with eosinophils;

bronchial smooth muscle cell hypertrophy and hyperreactivity;

and increased mucus secretion.

Sometimes trivial stimuli are sufficient to trigger attacks in patients, because of airway hyperreactivity.

Many cells play a role in the inflammatory response, in particular eosinophils, mast cells, macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and epithelial cells.

Pathogenesis

Major factors contributing to the development of asthma include genetic predisposition to type I hypersensitivity (atopy), acute and chronic airway inflammation, and bronchial hyper responsiveness to a variety of stimuli.Asthma may be subclassified as atopic (evidence of allergen sensitization) or nonatopic.

In both types, episodes of bronchospasm may be triggered by diverse exposures, such as respiratory infections (especially viral), airborne irritants (e.g., smoke, fumes), cold air, stress, and exercise.

The classic atopic form is associated with classic type I HSR.

Repeated bouts of inflammation lead to structural changes in the bronchial wall that are collectively referred to as airway remodeling. These changes include hypertrophy of bronchial smooth muscle and mucus glands and increased vascularity and deposition of subepithelial

collagen, which may occur as early as several years before initiation of symptoms.

TYPES:

Atopic asthma;

This is the most common type of asthma and is a classic example of type I IgE–mediated hypersensitivity reaction. It usually begins in childhood. A positive family history of atopy and/or asthma is common, and the onset of asthmatic attacks is often preceded by allergic rhinitis, urticaria, or eczema. Attacks may be triggered by allergens in dust, pollen, animal dander, or food, or by infections. A skin test with the offending antigen results in an immediate wheal-and-flare reaction. Atopic asthma also can be diagnosed based on serum radioallergosorbent tests (RASTs) that identify the presence of IgEs that recognize specific allergens.

Nonatopic asthma:

Patients with nonatopic forms of asthma do not have evidence of allergen sensitization, and skin test results usually are negative. A positive family history of asthma is less common. Respiratory infections due to viruses (e.g., rhinovirus, parainfluenza virus) and inhaled air pollutants are common triggers.It is thought that virus-induced inflammation of the respiratory mucosa lowers the threshold of the subepithelial vagal receptors to irritants. Although the connections are not well understood, the ultimate humoral and cellular mediators of airway obstruction (e.g., eosinophils) are common to both atopic and nonatopic variants of asthma, so they are treated in a similar way.

Drug-Induced asthma:

Several pharmacologic agents provoke asthma, aspirin being the most striking example. Patients with aspirin sensitivity present with recurrent rhinitis, nasal polyps, urticaria, and bronchospasm. The precise pathogenesis is unknown but is likely to involve some abnormality in prostaglandin metabolism stemming from inhibition of cyclooxygenaseby aspirin.

Occupational asthma:

Occupational asthma may be triggered by fumes, organic and chemical dusts (wood, cotton, platinum), gases (toluene), and other chemicals. Asthma attacks usually develop after repeated exposure to the inciting antigen(s).

Morphology of asthma;

• Thickening of airway wall• Sub-basement membrane fibrosis

• Increased submucosal vascularity

• An increase in size of the submucosal glands and goblet cell metaplasia of the airway epithelium

• Hypertrophy and/or hyperplasia of the bronchial muscle

Bronchiectasis

It is a disease characterized by permanent dilation of bronchi and bronchioles caused by destruction of the muscle and elastic tissue, resulting from or associated with chronic necrotizing infections.

To be considered bronchiectasis, dilation should be permanent; reversible bronchial dilation often accompanies viral and bacterial pneumonia.

Because of better control of lung infections, bronchiectasis is now an uncommon condition. It is manifested clinically by high fever, and expectoration of copious amounts of fouling, purulent sputum. Bronchiectasis develops in association with a variety of conditions, which include the following:

• Postinfectious conditions,

including necrotizing pneumonia caused by bacteria (Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas), viruses (adenovirus, influenza virus, HIV), and fungi (Aspergillus species).

• Bronchial obstruction,

owing to tumor, foreign bodies, and occasionally mucus impaction, in which the bronchiectasis is localized to the obstructed lung segment.

• Other conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, and post-transplantation.

Etiology and Pathogenesis.

Obstruction and infection are the major influences associated with bronchiectasis, and it is likely that both are necessary for the development of full-fledged lesions, although either may come first.After bronchial obstruction (e.g., by mucus impaction, tumors, or foreign bodies), normal clearing mechanisms are impaired, there is pooling of secretions distal to the obstruction, and there is inflammation of the airway.

Conversely, severe infections of the bronchi lead to inflammation, often with necrosis, fibrosis, and eventually dilatation of airways.

These mechanisms—infection and obstruction—are most readily apparent in the severe form of bronchiectasis associated with cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis

In this disorder, the primary defect in chloride transport leads to impaired secretion of chloride ions into mucus, low sodium and water content, defective mucociliary action, and accumulation of thick viscid secretions that obstruct the airways.

This leads to a marked susceptibility to bacterial infections, which further damage the airways. With repeated infections, there is widespread damage to airway walls, with destruction of supporting smooth muscle and elastic tissue, fibrosis, and further dilatation of bronchi.

The smaller bronchioles become progressively obliterated owing to fibrosis (bronchiolitis obliterans).

In primary ciliary dyskinesia,

an autosomal-recessive syndrome

poorly functioning cilia contribute to the retention of secretions and recurrent infections that in turn lead to bronchiectasis.

There is an absence or shortening of the dynein arms that are responsible for the coordinated bending of the cilia.

Approximately half of the patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia have Kartagener syndrome (bronchiectasis, sinusitis, and situs inversus or partial lateralizing abnormality).

The lack of ciliary activity interferes with bacterial clearance, predisposes the sinuses and bronchi to infection, and affects cell motility during embryogenesis, resulting in the situs inversus.

Males with this condition tend to be infertile, owing to ineffective mobility of the sperm tail.

Morphology.

Bronchiectasis usually affects the lower lobes bilaterally, particularly air passages that are vertical, and is most severe in the more distal bronchi and bronchioles.

When tumors or aspiration of foreign bodies leads to bronchiectasis, the involvement may be sharply localized to a single segment of the lung.

The airways are dilated, sometimes up to four times normal size. These dilations may produce long, tube like enlargements (cylindrical bronchiectasis) or, in other cases, may cause fusiform or even sharply saccular distention

Characteristically, the bronchi and bronchioles are sufficiently dilated that they can be followed, on gross examination, directly out to the pleural surfaces. By contrast, in the normal lung, the bronchioles cannot be followed by ordinary gross dissection beyond a point 2 to 3cm removed from the pleural surfaces.

On the cut surface of the lung, the transected dilated bronchi appear as cysts filled with mucopurulent secretions.

The histologic findings vary with the activity and chronicity of the disease. In the full-blown, active case:

there is an intense acute and chronic inflammatory exudation within the walls of the bronchi and bronchioles,

associated with desquamation of the lining epithelium and extensive areas of necrotizing ulceration.

There may be squamous metaplasia of the remaining epithelium.

In some instances, the necrosis completely destroys the bronchial or bronchiolar walls and forms a lung abscess.

Fibrosis of the bronchial and bronchiolar walls and peribronchiolar fibrosis develop in the more chronic cases, leading to varying degrees of subtotal or total obliteration of bronchiolar lumina.

Clinical Course. Bronchiectasis causes severe, persistent cough; expectoration of foul-smelling, sometimes bloody sputum; dyspnea and orthopnea in severe cases; and occasional life-threatening hemoptysis.

Complications Cor pulmonale, metastatic brain abscesses, and amyloidosis.

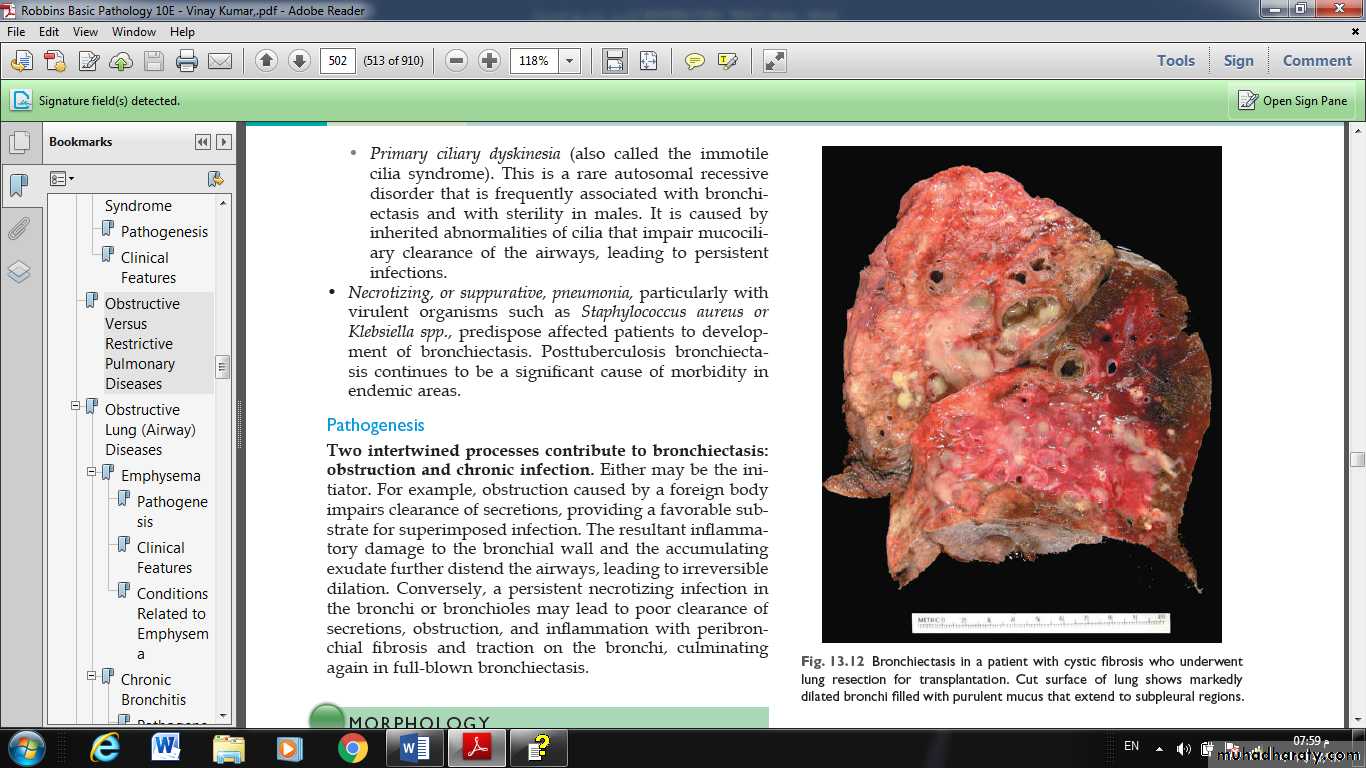

Fig. Bronchiectasis in a patient with cystic fibrosis who underwent lung resection for transplantation. Cut surface of lung shows markedly

dilated bronchi filled with purulent mucus that extend to subpleural regions.