Post-traumatic & postoperative osteomyelitis

ExogenousThey are the most common cause of osteomyelitis in adults.

Direct entry through a wound.

It often becomes chronic.

Occurs in children or in adults.

Staphylococcus aureus is the usual pathogen, but other organisms such as E. coli, Proteus mirabilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are sometimes involved. Occasionally, anaerobic organisms (clostridia, anaerobic streptococci or Bacteroides) appear in contaminated wounds.

Clinical features;

The patient becomes feverish and develops pain and swelling over the fracture site; the wound is inflamed and there may be a seropurulent discharge.Treatment:

The essence of treatment is prophylaxis: thorough cleansing and debridement of open fractures, the provision of drainage by leaving the wound open, immobilization of the fracture and antibioticsPyogenic infection, once it occurs, is difficult to eradicate:

Thorough cleansing and debridement.

Secure free drainage through the wound.

Secure fracture fixation.

Appropriate antibiotics.

Any dead bone fragments are removed.

Acute pyogenic arthritis (Infective, septic arthritis)

Is a form of arthritis in which a joint is infected by a bacteria of pyogenic group. When pus formed within the joint the condition is some time termed Acute suppurative arthritis.

A joint can become infected by:

Direct invasion through a penetrating wound, intra-articular injection or arthroscopy;

Direct spread from an adjacent bone abscess; or

Blood spread from a distant site.

The causal organisms:

Usually Staphylococcus aureus, in children between 1 and 4 years old, Haemophilus influenzae is an important pathogen. Occasionally other microbes, such as Streptococcus, Escherichia coli and Proteus, are encountered. Neisseria gonorhoea may encountered in adults.

Risk factors:

Artificial joint implants.Bacterial infection elsewhere in the body.

Chronic disease.

Intravenous drug abuse.

Medications that suppress immune system.

Recent joint trauma.

Recent joint arthroscopy or other surgery.

Pathology:

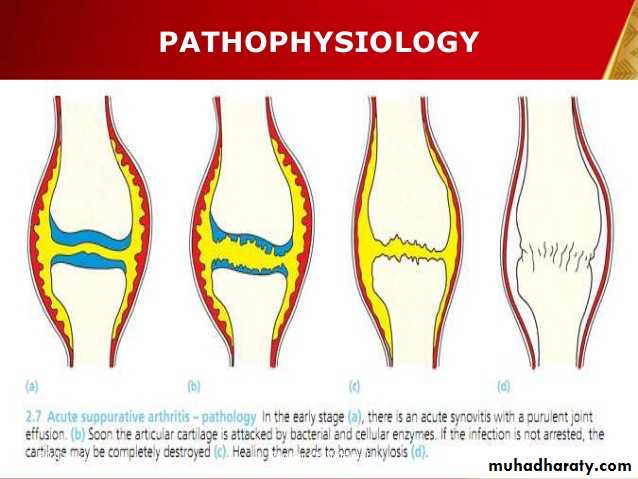

The infecting micro organisms settle in the synovial membrane inducing an acute inflammatory reaction. In the early stage (a), there is an acute synovitis with a seropurulent exudate and increase in synovial fluid.As pus appears in the joint, soon the articular cartilage is attacked by bacterial and cellular enzymes and eroded(b).

If the infection is not arrested, the cartilage may be completely destroyed (c). Healing then leads to bony ankylosis (d).

Clinical features:

In children:Acute pain in a single large joint (commonly the hip or the knee) and reluctance to move the limb (‘pseudoparesis’).

The child is ill, with a rapid pulse and a swinging fever.

The overlying skin looks red and in a superficial joint swelling may be obvious.

There is local warmth and marked tenderness.

All movements are restricted, and often completely abolished, by pain and spasm.

It is essential to look for a source of infection – a septic toe, a boil or a discharge from the ear.

The clinical features differ somewhat according to the age of the patient.

Imaging:

Ultrasonography: is a reliable method for revealing a joint effusion in early cases.X-ray: is normal early, then there will be widening of the radiographic ‘joint space’ and slight subluxation. Narrowing and irregularity of the joint space are late features.

MRI and CT: detection of early bone destruction and effusion.

Investigations

The white cell count, CRP, and ESR are raised.

Blood culture may be positive.

Joint aspiration is quicker (and usually more reliable). It may reveal frank pus. Samples of fluid are sent for full microbiological examination and tests for antibiotic sensitivity.

Treatment:

The first priority is to aspirate the joint and examine the fluid. Treatment is then started without further delay and follows the same lines as for acute osteomyelitisGeneral supportive treatment for pain and dehydration.

Splintage of the affected part.

Appropriate antimicrobial therapy: Antibiotic treatment follows the same guidelines as presented for acute haematogenous osteomyelitis.

Surgical drainage under anaesthesia: by arthrotomy , arthroscopy or by repeated aspiration.

Complications:

Articular cartilage destruction (chondrolysis).Bone destruction.

Subluxation and dislocation of the joint (pathological).

Growth plate destruction and growth retardation.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is a chronic granulomatous infection which can affects the skeleton: spine is the most common site (tuberculous spondylitis): it accounts for 50 per cent of all musculoskeletal tuberculosis ; and the large synovial joints as hip and knee joints (tuberculous arthritis) also may be affected. Long bones sometimes infected (tuberculous osteomyelitis).Pathogenesis:

The predisposing factors:

Chronic debilitating disease.

Diabetes

Drug abuse.

Prolonged corticosteroid medication.

AIDS

Poverty and over crowding.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (usually human, sometimes bovine) enters the body via the lung or the gut.

The initial lesion in lung, pharynx or gut is a small with regional lymph nodes involvement (primary complex).

Often, blood spread occurs months or years later, perhaps during a period of lowered immunity (Secondary spread), and bacilli are then deposited in extrapulmonary tissues (‘tertiary’ lesion).

Tertiary lesion affects bones or joints in about 5 per cent of patients with tuberculosis.

There is a predilection for the vertebral bodies and the large synovial joints.

Pathology

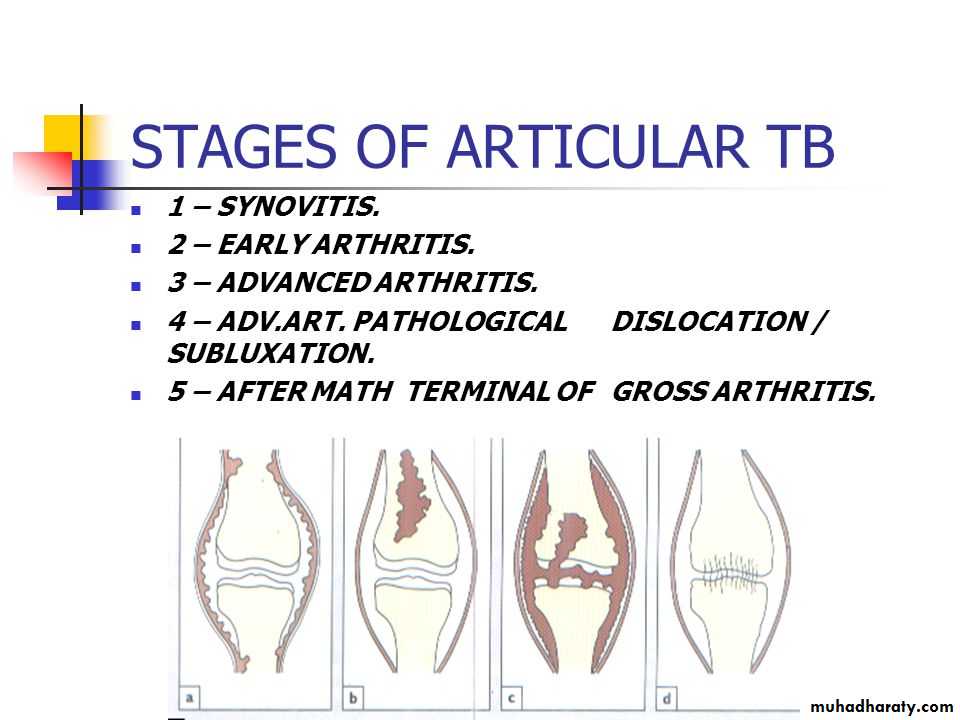

The disease may begin as synovitis (a) or osteomyelitis (b).From either, it can extend to become a true arthritis (c); not all the cartilage is destroyed, and healing is usually by fibrous ankylosis(d).

If the synovium is involved, it becomes thick and oedematous, giving rise to a marked effusion.

If unchecked, infection extend into the surrounding soft tissues to produce an abscess with minimal inflammatory reaction‘cold’ abscess.

This may burst through the skin, forming a sinus or tuberculous ulcer, or it may track along the tissue planes to point at some distant site. Secondary infection by pyogenic organisms is common.

In the spine (Pott’s disease), the most common site is the thoracolumbar spine, it is usually involve the anterior part of the vertebral body adjacent to the intervertebral disc space which is also involved early in the disease.

Abscess tracks downward along the vertebral column or it may extend toward the spinal canal.

Clinical features

There may be a history of previous infection or recent contact with tuberculosis.The patient, usually a child or young adult, complains of pain exacerbated at night ‘night cries’, and (in a superficial joint) there may be swelling.

In advanced cases there may be attacks of fever, night sweats, lassitude and loss of weight.

Muscle wasting above and below the joint is characteristic and synovial thickening is often striking (spindling of the joint).

Regional lymph nodes may be enlarged and tender.

Movements are limited in all directions. As articular erosion progresses the joint becomes stiff and deformed.

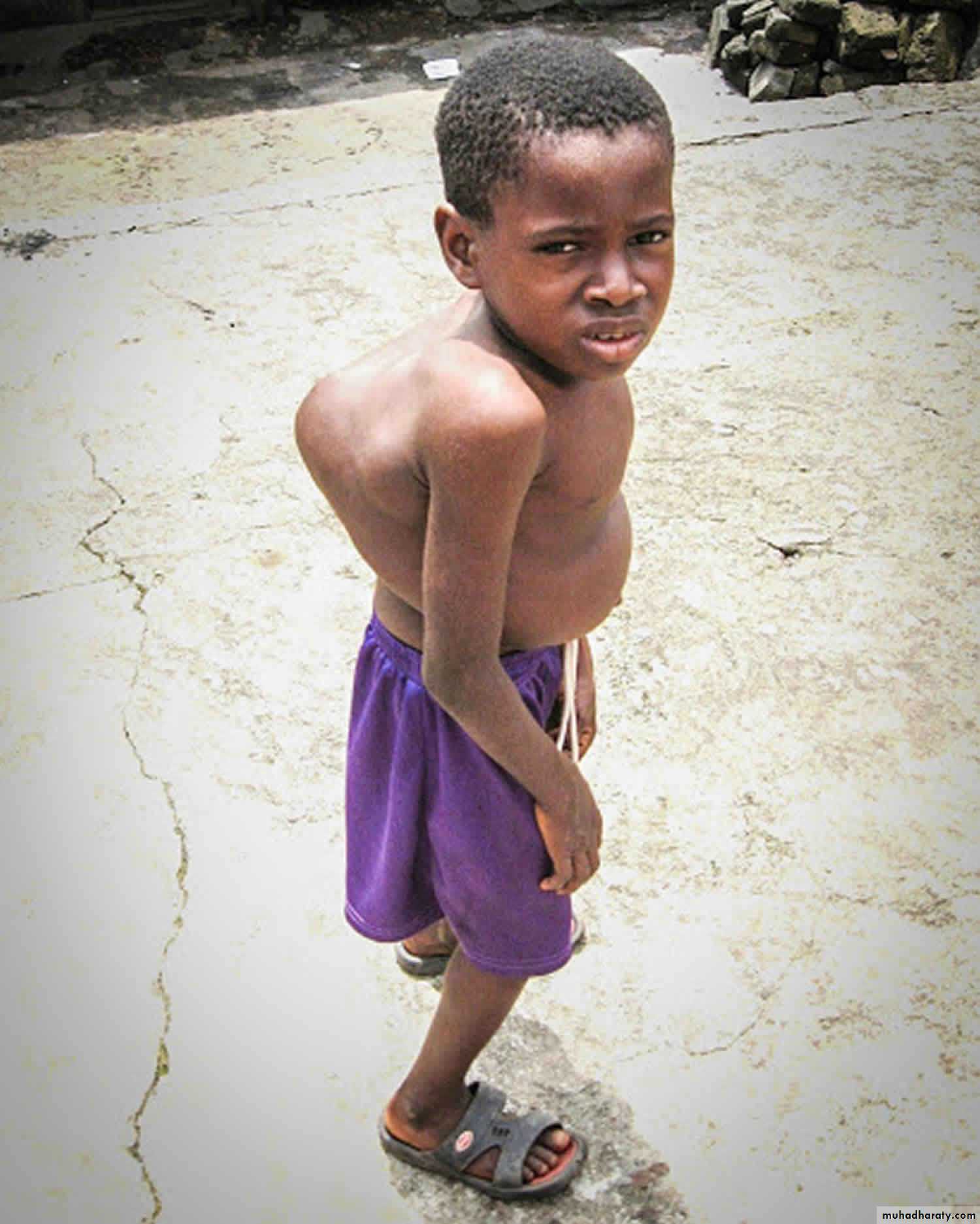

In the spine, pain may be slight. Consequently the patient may not present until there is a visible abscess (usually in the groin or the lumbar region to one side of the midline) or until collapse causes a localized angular kyphosis (gibbus).

Occasionally the presenting feature is weakness or instability in the lower limbs.

Pott’s paraplegia:

Paraplegia is the most feared complication of spinal tuberculosis.Early-onset: paresis (usually within 2 years of disease onset) is due to pressure by inflammatory oedema, abscess, caseous material, granulation tissue or sequestra. In these cases the prognosis for neurological recovery following surgery is good.

Late onset: paresis is due to direct cord compression from increasing deformity, or (occasionally) vascular insufficiency of the cord; recovery following decompression is poor.

Imaging:

Pain x-ray:Priarticular osteoporosis,

Bone erosion and cystic lesion (on either sides of the joint) with little or no periosteal reaction, and

Progressive narrowing of joint space (phemister triad).

In the spine the characteristic appearance is one of bone erosion and collapse around a diminished intervertebral disc space (kissing vertebrae). The soft-tissue shadows may define a paravertebral abscess.

MRI: assess the extent of nerve tissue affection.

CXR is mandatory.

Laboratory Investigations:

ESR and WBC: increased with relative lymphocytosis, Hb is low.

Mantoux skin test or Heaf test may be positive.

Joint aspiration: the synovial fluid is cloudy.

Tuberculous bacilli in the synovial fluid by AFB (10-20%) or by culture (over 50%).

Synovial or bone biopsy: the characteristic tuberculous granuloma and cultures are positive in about 80% of cases.

Diagnosis

Except in areas where tuberculosis is common, diagnosis is often delayed simply because the disease is not suspected. Features that should trigger more active investigation are:

Long history of joint pain or swelling.

of only one joint.

Marked synovial thickening.

muscle wasting.

Enlarged and matted regional lymph nodes.

Periarticular osteoporosis on x-ray.

Positive Mantoux test.

Synovial biopsy for histological examination and culture is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Rest: splintage of the joint and traction.

Chemotherapy: The most effective treatment is a combination of antituberculous drugs, which should always include rifampicin and isoniazid. Treatment is continued for 6–12.

Operation:

Should be done after starting effective chemotherapy:

Cold abscess: need aspiration or drainage.

Arthrotomy: for biopsy or synovectomy.

Joint arthrodesis or arthroplasty may be considered for deformed unstable joint.

In the spine surgery is indicated when there is

An abscess;

Marked bone destruction and threatened or actual severe kyphosis;

Neurological deficit including paraparesis not responded to drug therapy.

Surgical decompression with anterior or posterior fixation and fusion may be needed for additional stability.