208

DIVISIONS OF THE GUT TUBE

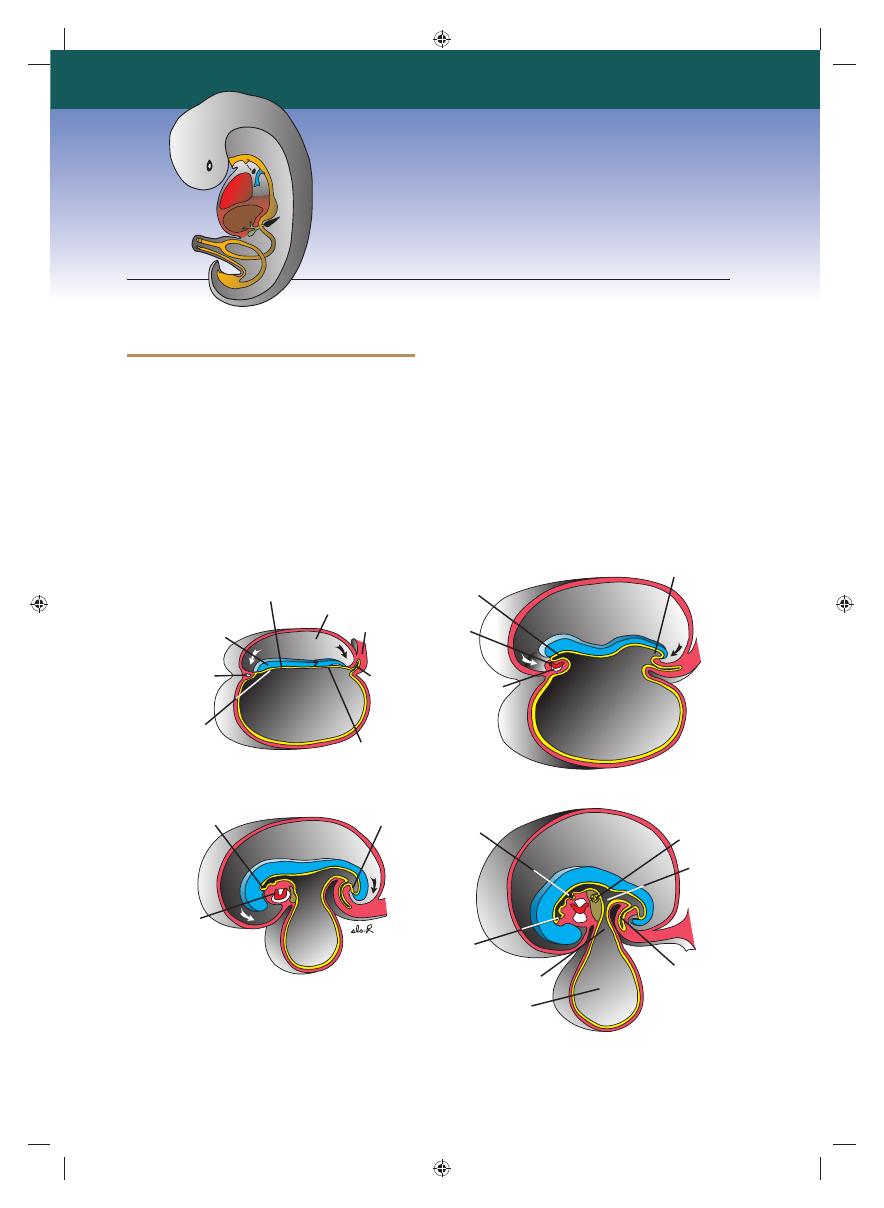

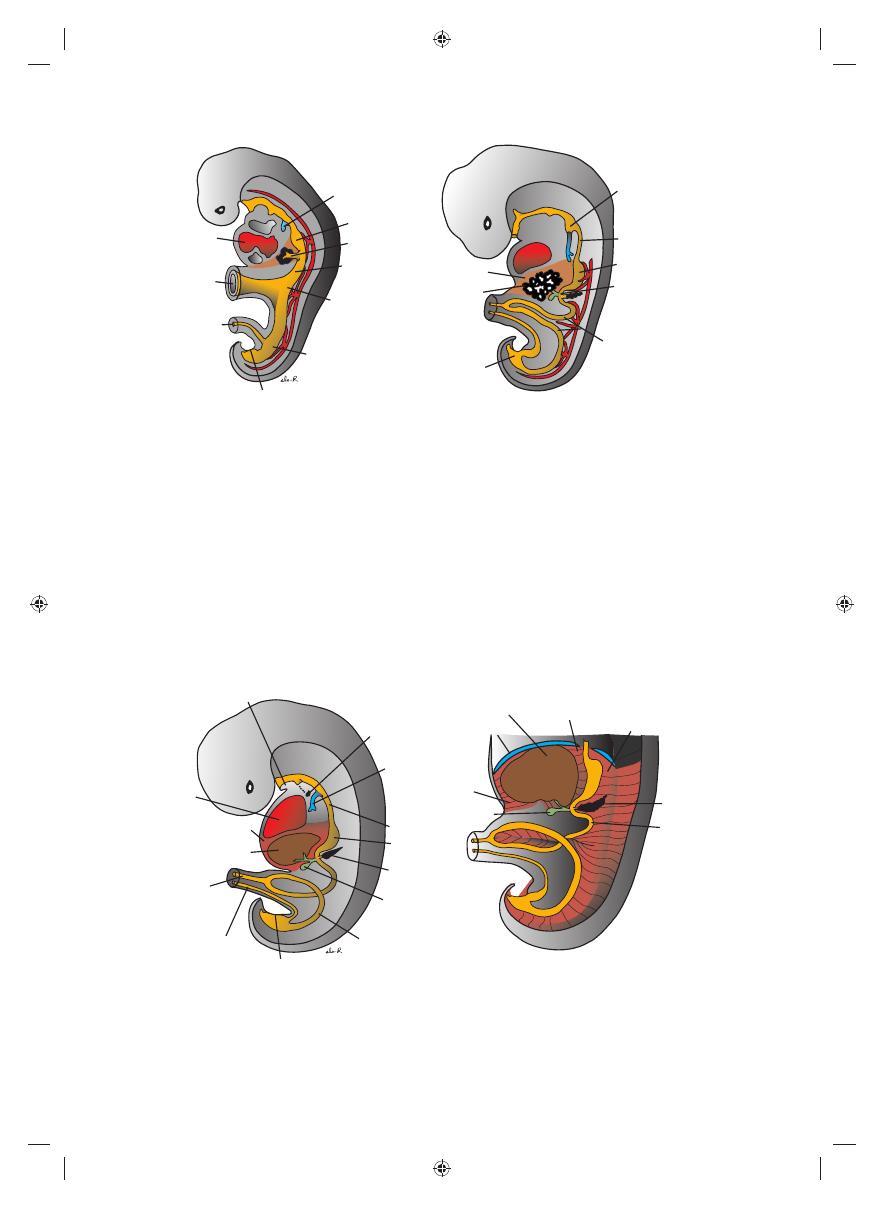

As a result of cephalocaudal and lateral folding

of the embryo, a portion of the endoderm-lined

yolk sac cavity is incorporated into the embryo

to form the primitive gut. Two other por-

tions of the endoderm-lined cavity, the yolk sac

and the allantois, remain outside the embryo

(Fig. 15.1A–D).

In the cephalic and caudal parts of the embryo,

the primitive gut forms a blind-ending tube, the

foregut

and hindgut, respectively. The middle

part, the midgut, remains temporally connected

to the yolk sac by means of the vitelline duct, or

yolk stalk

(Fig. 15.1D).

Development of the primitive gut and its

derivatives is usually discussed in four sections: (a)

The pharyngeal gut, or pharynx, extends from

the oropharyngeal membrane to the respiratory

diverticulum and is part of the foregut; this sec-

tion is particularly important for development of

the head and neck and is discussed in Chapter 17.

(b) The remainder of the foregut lies caudal to

the pharyngeal tube and extends as far caudally as

the liver outgrowth. (c) The midgut begins cau-

dal to the liver bud and extends to the junction

Chapter

15

Digestive System

Ectoderm

Angiogenic

cell cluster

Amniotic cavity

Endoderm

Connecting

stalk

Allantois

Cloacal

membrane

Foregut

Pericardial

cavity

Heart

tube

Hindgut

Remnant

of the

oropharyngeal

membrane

Cloacal

membrane

Heart

tube

Oropharyngeal

membrane

Vitelline duct

Lung bud

Liver

bud

Midgut

Allantois

Yolk sac

A

C

B

D

Oropharyngeal

membrane

Figure 15.1

Sagittal sections through embryos at various stages of development demonstrating the effect of cephalocau-

dal and lateral folding on the position of the endoderm-lined cavity. Note formation of the foregut, midgut, and hindgut.

A. Presomite embryo. B. Embryo with seven somites. C. Embryo with 14 somites. D. At the end of the fi rst month.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 208

Sadler_Chap15.indd 208

8/26/2011 7:21:25 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:25 AM

Chapter 15 Digestive System

209

of the right two-thirds and left third of the trans-

verse colon in the adult. (d) The hindgut extends

from the left third of the transverse colon to the

cloacal membrane (Fig. 15.1). Endoderm forms

the epithelial lining of the digestive tract and

gives rise to the specifi c cells (the parenchyma)

of glands, such as hepatocytes and the exocrine

and endocrine cells of the pancreas. The stroma

(connective tissue) for the glands is derived from

visceral mesoderm. Muscle, connective tissue,

and peritoneal components of the wall of the gut

also are derived from visceral mesoderm.

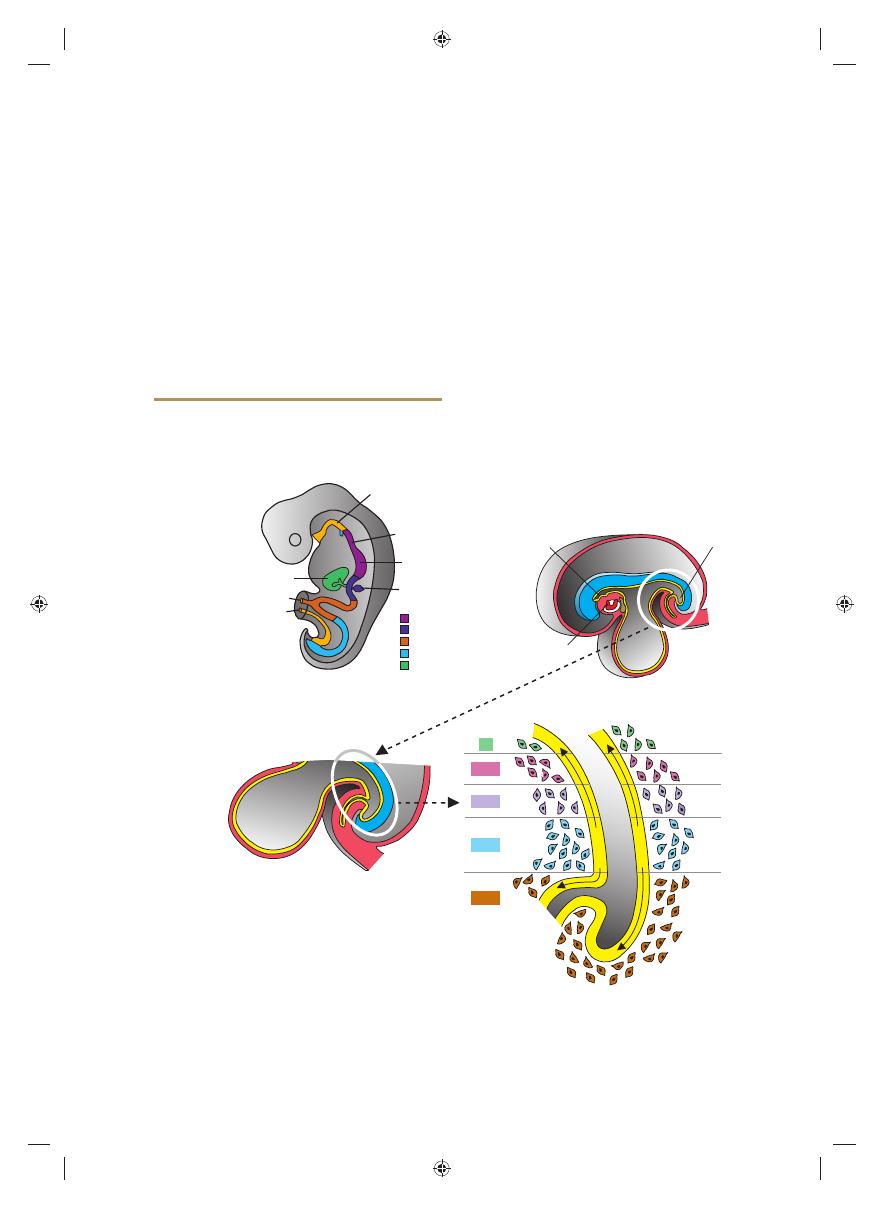

MOLECULAR REGULATION OF

GUT TUBE DEVELOPMENT

Regional specifi cation of the gut tube into differ-

ent components occurs during the time that the

lateral body folds are bringing the two sides of the

tube together (Figs. 15.2 and 15.3). Specifi cation

is initiated by a concentration gradient of retinoic

acid (RA) from the pharynx, that is exposed to

little or no RA, to the colon, that sees the highest

concentration of RA. This RA gradient causes

transcription factors to be expressed in different

regions of the gut tube. Thus, SOX2 “specifi es”

the esophagus and stomach; PDX1, the duode-

num; CDXC, the small intestine; and CDXA,

the large intestine and rectum (Fig. 15.2A).

This initial patterning is stabilized by reciprocal

interactions between the endoderm and visceral

mesoderm adjacent to the gut tube (Fig. 15.2B–

D). This epithelial–mesenchymal interaction

is initiated by sonic hedgehog (SHH) expres-

sion throughout the gut tube. SHH expression

upregulates factors in the mesoderm that then

determine the type of structure that forms from

the gut tube, such as the stomach, duodenum,

9-10

9

9-11

9-12

9-13

S

H

H

S

H

H

Hindgut

Heart

tube

Foregut

small

intestine

cecum

large

intestine

cloaca

HOX

Allantois

A

C

D

B

Vitelline duct

Liver

Pancreas

CSOX2

PDX1

CDXC

CDXA

HOX

Stomach

Esophagus

Pharyngeal gut

Figure 15.2

Diagrams showing molecular regulation of gut development. A. Color-coded diagram that indicates genes

responsible for initiating regional specifi cation of the gut into esophagus, stomach, duodenum, etc. B-D. Drawings showing

an example from the midgut and hindgut regions indicating how early gut specifi cation is stabilized. Stabilization is effected

by epithelial–mesenchymal interactions between gut endoderm and surrounding visceral (splanchnic) mesoderm. Endoderm

cells initiate the stabilization process by secreting SHH, which establishes a nested expression of HOX genes in the meso-

derm. This interaction results in a genetic cascade that regulates specifi cation of each gut region as is shown for the small

and large intestine regions in these diagrams.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 209

Sadler_Chap15.indd 209

8/26/2011 7:21:25 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:25 AM

210

Part II Systems-Based Embryology

enclose an organ and connect it to the body wall.

Such organs are called intraperitoneal, whereas

organs that lie against the posterior body wall and

are covered by peritoneum on their anterior sur-

face only (e.g., the kidneys) are considered retro-

peritoneal. Peritoneal ligaments

are double

layers of peritoneum (mesenteries) that pass from

one organ to another or from an organ to the

body wall. Mesenteries and ligaments provide

pathways for vessels, nerves, and lymphatics to

and from abdominal viscera (Figs. 15.3 and 15.4).

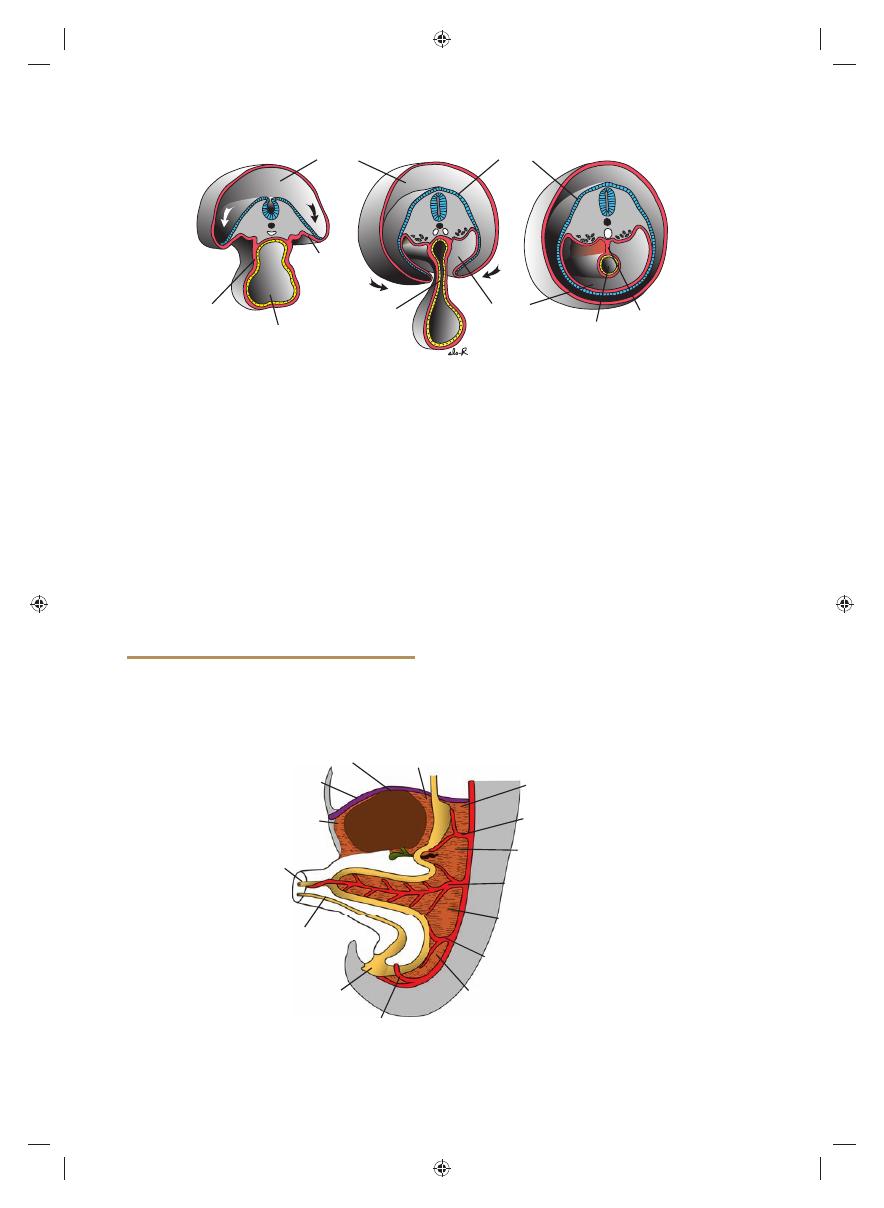

Initially the foregut, midgut, and hindgut are

in broad contact with the mesenchyme of the

posterior abdominal wall (Fig. 15.3). By the fi fth

week, however, the connecting tissue bridge has

small intestine, etc. For example, in the region

of the caudal limit of the midgut and all of the

hindgut, SHH expression establishes a nested

expression of the HOX genes in the mesoderm

(Fig. 15.2D). Once the mesoderm is specifi ed by

this code, then it instructs the endoderm to form

the various components of the mid- and hindgut

regions, including part of the small intestine,

cecum, colon, and cloaca (Fig. 15.2).

MESENTERIES

Portions of the gut tube and its derivatives are sus-

pended from the dorsal and ventral body wall by

mesenteries

, double layers of peritoneum that

Amnionic cavity

Surface ectoderm

Gut

Dorsal

mesentery

Intra-

embryonic

body cavity

Connection

between

gut and yolk sac

Visceral

mesoderm

Parietal

mesoderm

Yolk sac

A

B

C

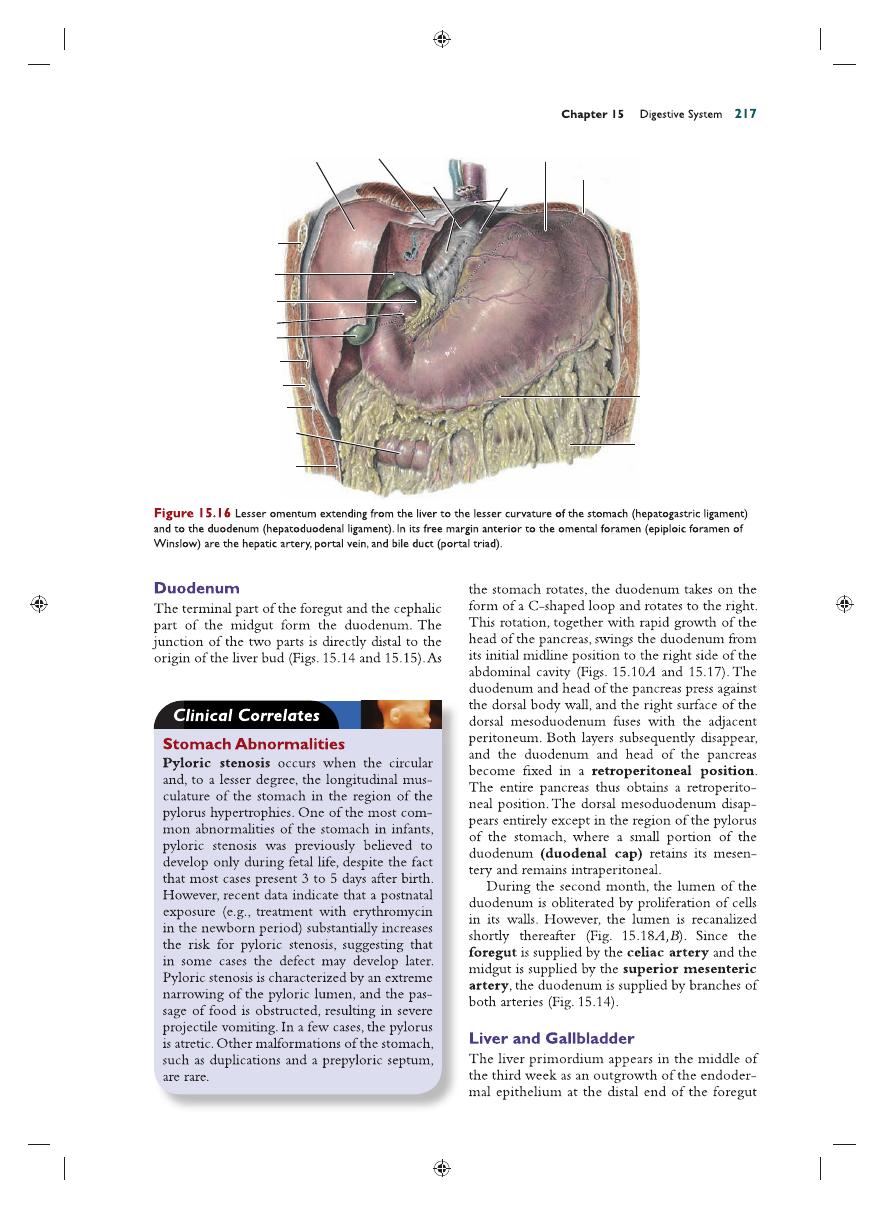

Figure 15.3

Transverse sections through embryos at various stages of development. A. The intraembryonic cavity,

bordered by visceral and somatic layers of lateral plate mesoderm, is in open communication with the extraembryonic cavity.

B. The intraembryonic cavity is losing its wide connection with the extraembryonic cavity. C. At the end of the fourth week,

visceral mesoderm layers are fused in the midline and form a double-layered membrane (dorsal mesentery) between right

and left halves of the body cavity. Ventral mesentery exists only in the region of the septum transversum (not shown).

Celiac artery

Dorsal mesogastrium

Bare area of liver

Diaphragm

Falciform ligament

Vitelline duct

Allantois

Cloaca

Umbilical artery

Lesser

omentum

Dorsal mesocolon

Dorsal mesoduodenum

Superior mesenteric artery

Inferior mesenteric artery

Mesentery proper

Figure 15.4

Primitive dorsal and ventral mesenteries. The liver is connected to the ventral abdominal wall and to the

stomach by the falciform ligament and lesser omentum, respectively. The superior mesenteric artery runs through the mes-

entery proper and continues toward the yolk sac as the vitelline artery.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 210

Sadler_Chap15.indd 210

8/26/2011 7:21:26 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:26 AM

Chapter 15 Digestive System

211

ventral mesentery into (a) the lesser omentum,

extending from the lower portion of the esopha-

gus, the stomach, and the upper portion of the

duodenum to the liver and (b) the falciform

ligament

, extending from the liver to the ventral

body wall (Fig. 15.4; see Chapter 7).

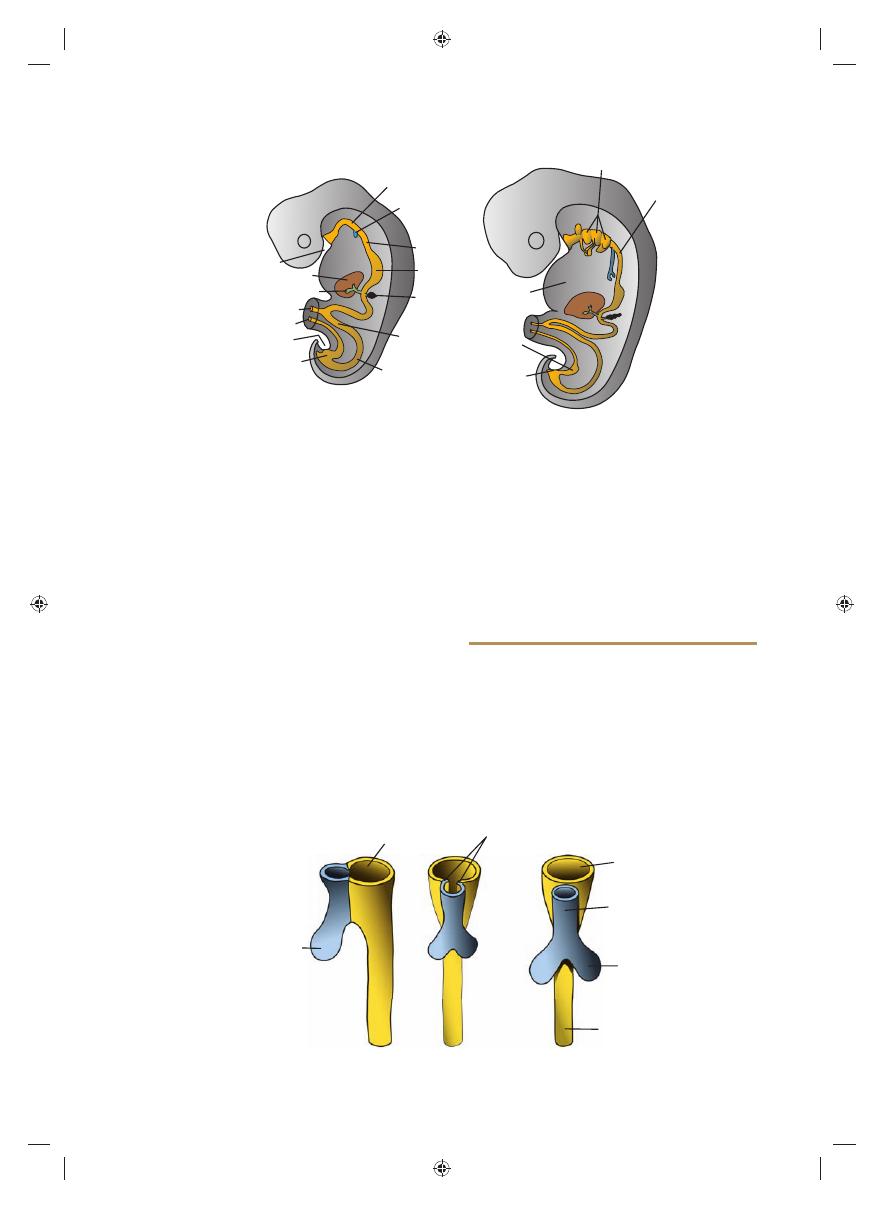

FOREGUT

Esophagus

When the embryo is approximately 4 weeks old,

the respiratory diverticulum (lung bud)

appears at the ventral wall of the foregut at the

border with the pharyngeal gut (Fig. 15.5). The

tracheoesophageal septum

gradually parti-

tions this diverticulum from the dorsal part of

the foregut (Fig. 15.6). In this manner, the foregut

narrowed, and the caudal part of the foregut,

the midgut, and a major part of the hindgut are

suspended from the abdominal wall by the dor-

sal mesentery

(Figs. 15.3C and 15.4), which

extends from the lower end of the esophagus to

the cloacal region of the hindgut. In the region of

the stomach, it forms the dorsal mesogastrium

or greater omentum; in the region of the duo-

denum, it forms the dorsal mesoduodenum;

and in the region of the colon, it forms the dor-

sal mesocolon.

Dorsal mesentery of the jejunal

and ileal loops forms the mesentery proper.

Ventral mesentery

, which exists only in the

region of the terminal part of the esophagus, the

stomach, and the upper part of the duodenum

(Fig. 15.4), is derived from the septum trans-

versum.

Growth of the liver into the mesen-

chyme of the septum transversum divides the

A

B

Hindgut

Cloaca

Proctodeum

Allantois

Vitelline duct

Gallbladder

Liver

Stomodeum

Cloacal

membrane

Urinary

bladder

Heart

bulge

Pharyngeal

pouches

Esophagus

Pancreas

Stomach

Esophagus

Tracheo-

bronchial

diverticulum

Pharyngeal gut

Primitive

intestinal

loop

Figure 15.5

Embryos during the fourth A and fi fth B weeks of development showing formation of the gastrointesti-

nal tract and the various derivatives originating from the endodermal germ layer.

Tracheoesophageal

septum

Foregut

A

B

C

Pharynx

Trachea

Lung buds

Esophagus

Respiratory

diverticulum

Figure 15.6

Successive stages in development of the respiratory diverticulum and esophagus through partitioning of the

foregut. A. At the end of the third week (lateral view). B,C. During the fourth week (ventral view).

Sadler_Chap15.indd 211

Sadler_Chap15.indd 211

8/26/2011 7:21:26 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:26 AM

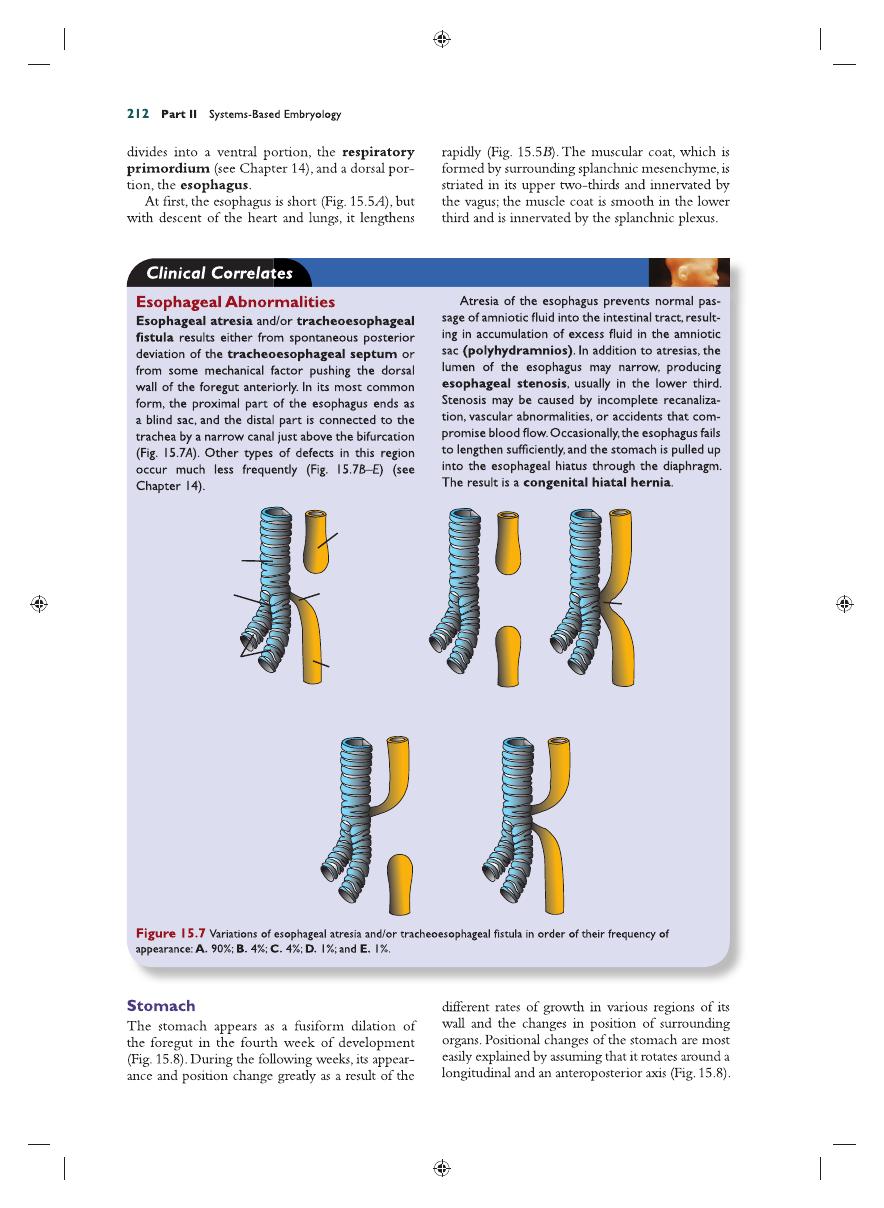

A

E

B

D

C

Trachea

Bifurcation

Bronchi

Tracheoesophageal

fistula

Distal part of

esophagus

Proximal blind-

end part of

esophagus

Communication

of esophagus

with trachea

Sadler_Chap15.indd 212

Sadler_Chap15.indd 212

8/26/2011 7:21:27 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:27 AM

Chapter 15 Digestive System

213

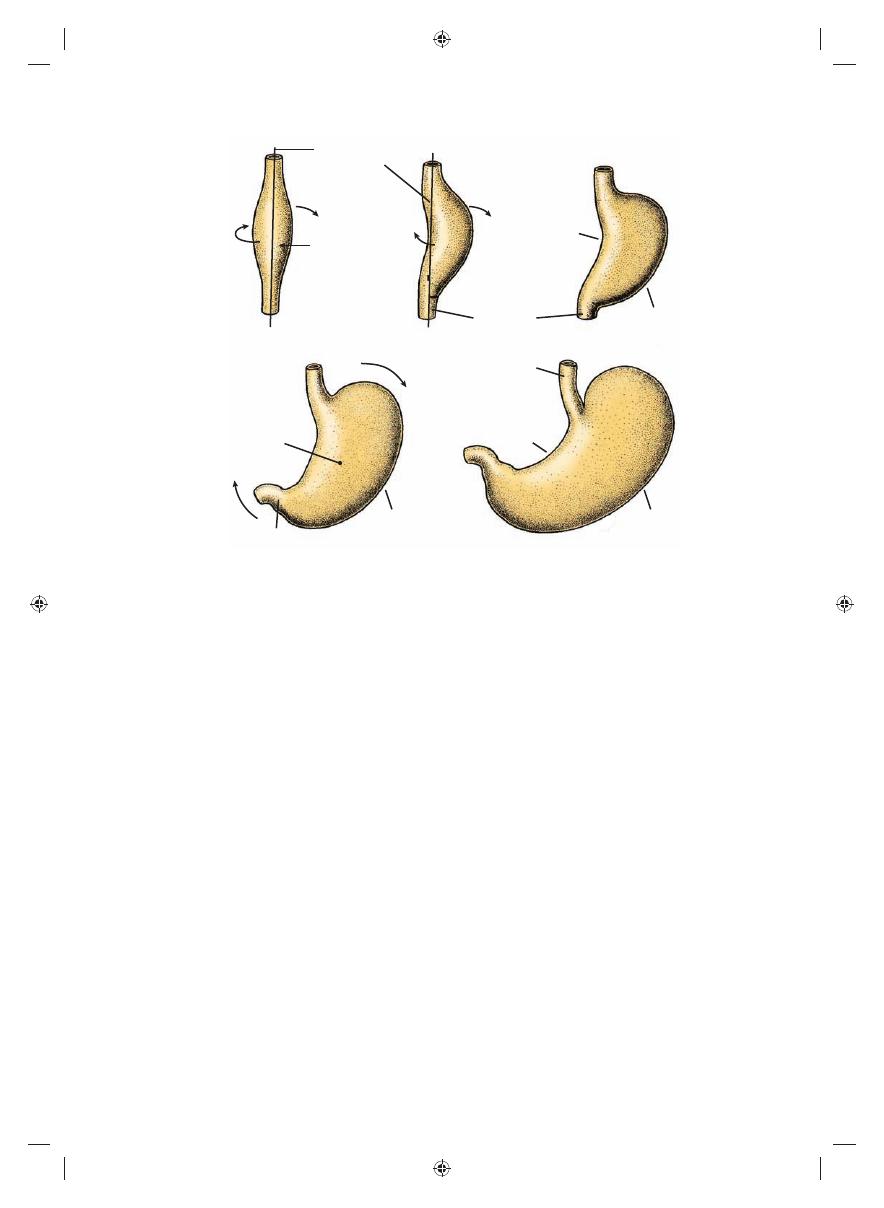

The stomach rotates 90° clockwise around its

longitudinal axis, causing its left side to face ante-

riorly and its right side to face posteriorly (Fig.

15.8A–C). Hence, the left vagus nerve, initially

innervating the left side of the stomach, now

innervates the anterior wall; similarly, the right

nerve innervates the posterior wall. During this

rotation, the original posterior wall of the stomach

grows faster than the anterior portion, forming

the greater and lesser curvatures (Fig. 15.8C).

The cephalic and caudal ends of the stomach

originally lie in the midline, but during further

growth, the stomach rotates around an antero-

posterior axis, such that the caudal or pyloric

part

moves to the right and upward, and the

cephalic or cardiac portion moves to the left

and slightly downward (Fig. 15.8D,E). The stom-

ach thus assumes its fi nal position, its axis running

from above left to below right.

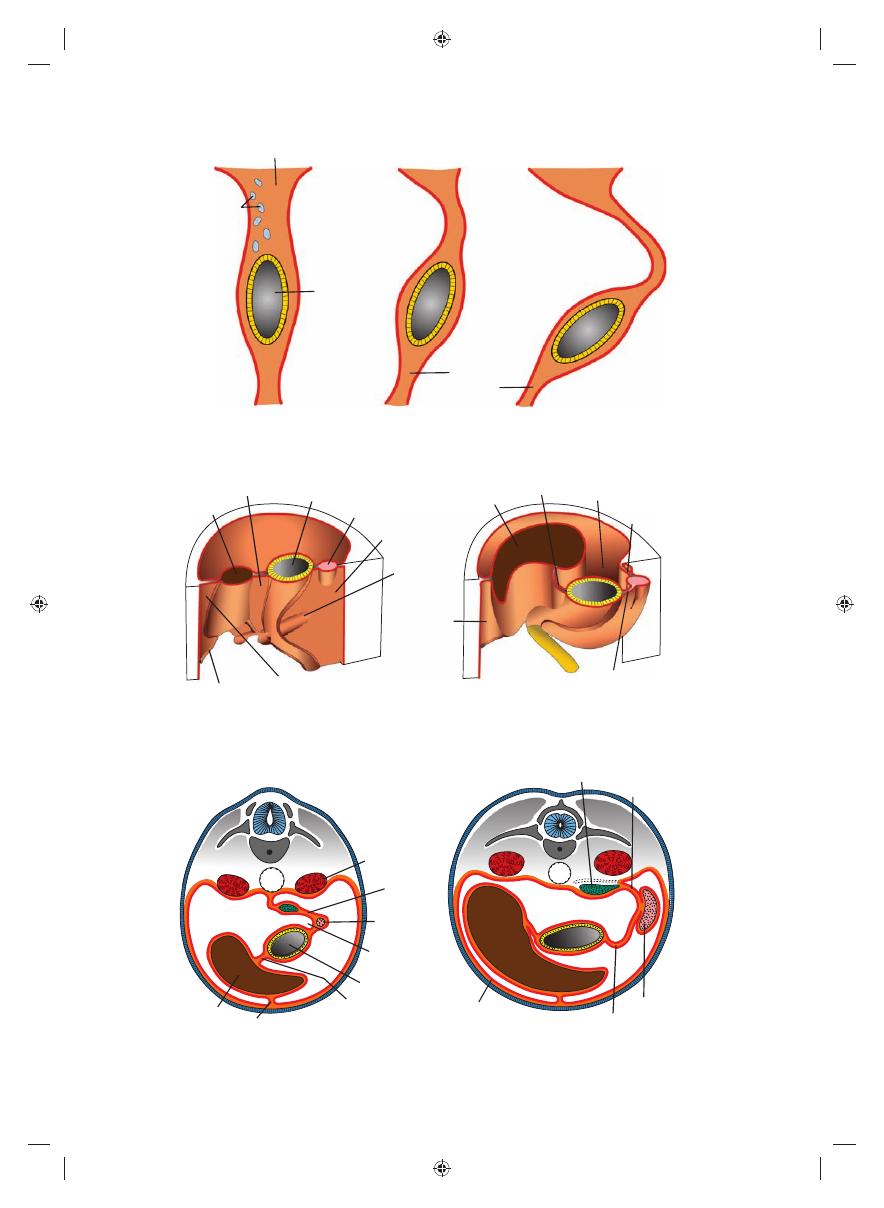

Since the stomach is attached to the dorsal

body wall by the dorsal mesogastrium and

to the ventral body wall by the ventral meso-

gastrium

(Figs. 15.4 and 15.9A), its rotation

and disproportionate growth alter the position

of these mesenteries. Rotation about the lon-

gitudinal axis pulls the dorsal mesogastrium to

the left, creating a space behind the stomach

called the omental bursa (lesser peritoneal

sac)

(Figs. 15.9 and 15.10). This rotation also

pulls the ventral mesogastrium to the right.

As this process continues in the fi fth week of

development, the spleen primordium appears

as a mesodermal proliferation between the

two leaves of the dorsal mesogastrium (Figs.

15.10 and 15.11). With continued rotation of

the stomach, the dorsal mesogastrium length-

ens, and the portion between the spleen and

dorsal midline swings to the left and fuses with

the peritoneum of the posterior abdominal

wall (Figs. 15.10 and 15.11). The posterior leaf

of the dorsal mesogastrium and the perito-

neum along this line of fusion degenerate. The

spleen, which remains intraperitoneal, is then

connected to the body wall in the region of

the left kidney by the lienorenal ligament

and to the stomach by the gastrolienal liga-

ment

(Figs. 15.10 and 15.11). Lengthening and

fusion of the dorsal mesogastrium to the poste-

rior body wall also determine the fi nal position

of the pancreas. Initially, the organ grows into

the dorsal mesoduodenum, but eventually its

tail extends into the dorsal mesogastrium (Fig.

15.10A). Since this portion of the dorsal meso-

gastrium fuses with the dorsal body wall, the

B

A

C

Longitudinal

rotation axis

Stomach

Lesser

curvature

Greater

curvature

Duodenum

Esophagus

D

E

Anteroposterior

axis

Lesser

curvature

Greater

curvature

Greater

curvature

Pylorus

Figure 15.8

A–C. Rotation of the stomach along its longitudinal axis as seen anteriorly. D,E. Rotation of the stomach

around the anteroposterior axis. Note the change in position of the pylorus and cardia.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 213

Sadler_Chap15.indd 213

8/26/2011 7:21:29 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:29 AM

214

Part II Systems-Based Embryology

Stomach

Dorsal mesogastrium

Small

vacuoles

Lesser

omentum

A

B

C

Omental

bursa

Figure 15.9

A. Transverse section through a 4-week embryo showing intercellular clefts appearing in the dorsal mesogas-

trium. B,C. The clefts have fused, and the omental bursa is formed as an extension of the right side of the intraembryonic

cavity behind the stomach.

Umbilical

vein

Gastrolienal

ligament

Omental

bursa

Lienorenal

ligament

Lesser

omentum

Liver

Falciform

ligament

Dorsal

pancreas

Dorsal

mesogastrium

Spleen

Stomach

Lesser omentum

Liver

Falciform ligament

A

B

Figure 15.10

A. The positions of the spleen, stomach, and pancreas at the end of the fi fth week. Note the position of the

spleen and pancreas in the dorsal mesogastrium. B. Position of spleen and stomach at the 11th week. Note formation of the

omental bursa (lesser peritoneal sac).

Liver

Spleen

Gastrolienal ligament

Parietal

peritoneum

of body wall

Lienorenal

ligament

Pancreas

Kidney

Dorsal

mesogastrium

Spleen

Omental

bursa

Stomach

Lesser omentum

Falciform ligament

A

B

Figure 15.11

Transverse sections through the region of the stomach, liver, and spleen, showing formation of the omental

bursa (lesser peritoneal sac), rotation of the stomach, and position of the spleen and tail of the pancreas between the two

leaves of the dorsal mesogastrium. With further development, the pancreas assumes a retroperitoneal position.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 214

Sadler_Chap15.indd 214

8/26/2011 7:21:30 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:30 AM

Chapter 15 Digestive System

215

down and forms a double-layered sac extend-

ing over the transverse colon and small intestinal

loops like an apron (Fig. 15.13A). This double-

leafed apron is the greater omentum; later, its

layers fuse to form a single sheet hanging from the

greater curvature of the stomach (Fig. 15.13B).

The posterior layer of the greater omentum also

fuses with the mesentery of the transverse colon

(Fig. 15.13B).

The lesser omentum and falciform liga-

ment

form from the ventral mesogastrium,

which itself is derived from mesoderm of the

septum transversum. When liver cords grow into

the septum, it thins to form (a) the peritoneum

tail of the pancreas lies against this region (Fig.

15.11). Once the posterior leaf of the dorsal

mesogastrium and the peritoneum of the pos-

terior body wall degenerate along the line of

fusion, the tail of the pancreas is covered by

peritoneum on its anterior surface only and

therefore lies in a retroperitoneal position.

(Organs, such as the pancreas, that are originally

covered by peritoneum, but later fuse with the

posterior body wall to become retroperitoneal,

are said to be secondarily retroperitoneal.)

As a result of rotation of the stomach about

its anteroposterior axis, the dorsal mesogastrium

bulges down (Fig. 15.12). It continues to grow

Greater curvature

of stomach

Greater

omentum

Descending

colon

Ascending

colon

Sigmoid

Duodenum

Esophagus

Dorsal

mesogastrium

Omental

bursa

Mesoduodenum

Mesocolon

Mesentery

proper

Appendix

A

B

Figure 15.12

A. Derivatives of the dorsal mesentery at the end of the third month. The dorsal mesogastrium bulges out

on the left side of the stomach, where it forms part of the border of the omental bursa. B. The greater omentum hangs

down from the greater curvature of the stomach in front of the transverse colon.

Greater

omentum

Omental

bursa

Greater omentum

Small intestinal loop

Mesentery

of transverse

colon

Duodenum

Pancreas

Peritoneum

of posterior

abdominal wall

Stomach

Omental

bursa

B

A

Figure 15.13

A. Sagittal section showing the relation of the greater omentum, stomach, transverse colon, and small intes-

tinal loops at 4 months. The pancreas and duodenum have already acquired a retroperitoneal position. B. Similar section as in

A in the newborn. The leaves of the greater omentum have fused with each other and with the transverse mesocolon. The

transverse mesocolon covers the duodenum, which fuses with the posterior body wall to assume a retroperitoneal position.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 215

Sadler_Chap15.indd 215

8/26/2011 7:21:31 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:31 AM

216

Part II Systems-Based Embryology

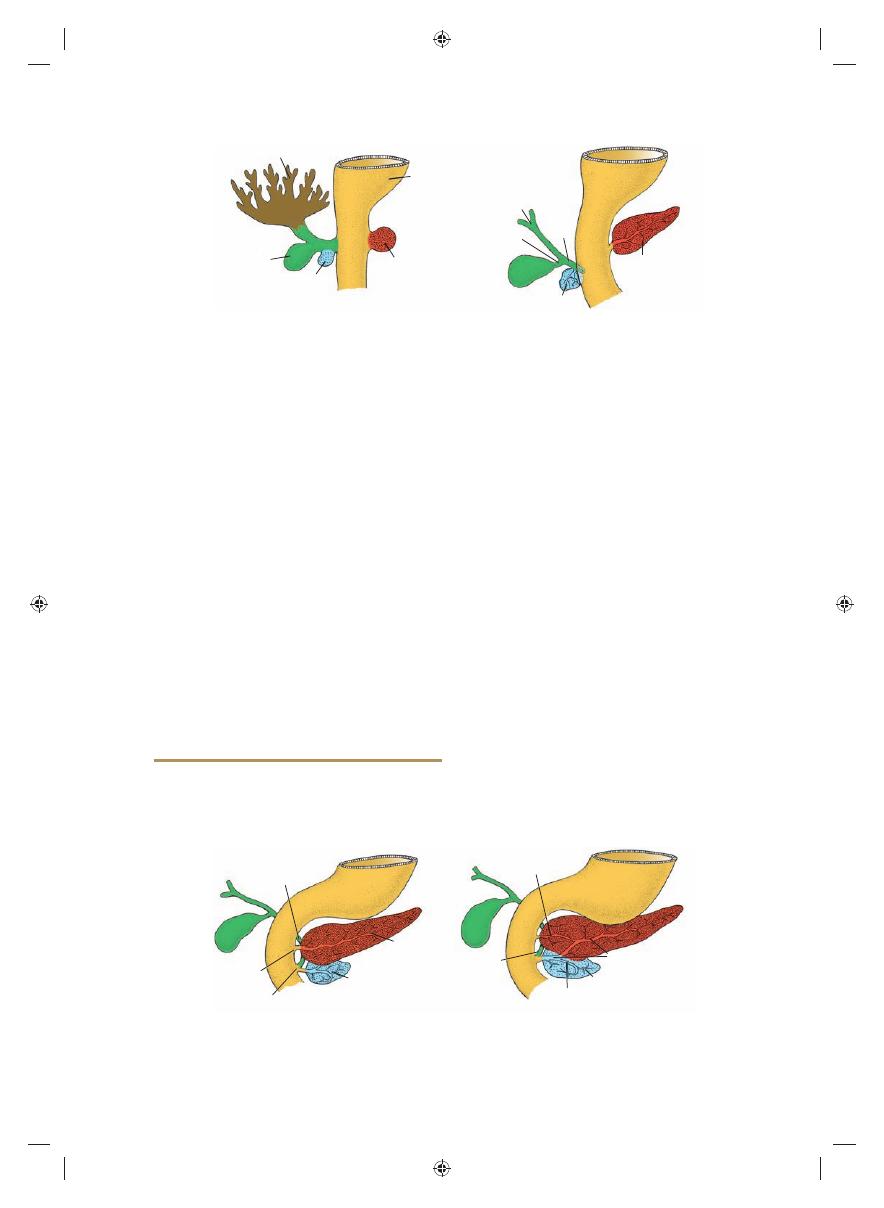

free margin of the lesser omentum connecting

the duodenum and liver (hepatoduodenal

ligament)

contains the bile duct, portal vein,

and hepatic artery (portal triad). This free

margin also forms the roof of the epiploic

foramen of Winslow

, which is the opening

connecting the omental bursa (lesser sac) with

the rest of the peritoneal cavity (greater sac)

(Fig. 15.16).

of the liver; (b) the falciform ligament,

extending from the liver to the ventral body

wall; and (c) the lesser omentum, extending

from the stomach and upper duodenum to the

liver (Figs. 15.14 and 15.15). The free margin

of the falciform ligament contains the umbili-

cal vein (Fig. 15.10A), which is obliterated

after birth to form the round ligament of

the liver (ligamentum teres hepatis)

. The

Respiratory

diverticulum

Heart

Vitelline

duct

Allantois

Cloacal

membrane

A

B

Hindgut

Liver bud

Duodenum

Midgut

Stomach

Septum

transversum

Liver

Cloaca

Duodenum

Stomach

Esophagus

Larynx

Primary

intestinal

loop

Figure 15.14

A. A 3-mm embryo (approximately 25 days) showing the primitive gastrointestinal tract and formation of

the liver bud. The bud is formed by endoderm lining the foregut. B. A 5-mm embryo (approximately 32 days). Epithelial liver

cords penetrate the mesenchyme of the septum transversum.

A

B

Hindgut

Vitelline

duct

Allantois

Liver

Cloacal membrane

Septum

transversum

Pericardial

cavity

Stomach

Gallbladder

Pancreas

Dorsal

mesogastrium

Lesser

omentum

Bare area of liver

Esophagus

Tracheobronchial

diverticulum

Thyroid

Diaphragm

Falciform

ligament

Gallbladder

Tongue

Pancreas

Duodenum

Figure 15.15

A. A 9-mm embryo (approximately 36 days). The liver expands caudally into the abdominal cavity. Note

condensation of mesenchyme in the area between the liver and the pericardial cavity, foreshadowing formation of the

diaphragm from part of the septum transversum. B. A slightly older embryo. Note the falciform ligament extending between

the liver and the anterior abdominal wall and the lesser omentum extending between the liver and the foregut (stomach

and duodenum). The liver is entirely surrounded by peritoneum except in its contact area with the diaphragm. This is the

bare area of the liver.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 216

Sadler_Chap15.indd 216

8/26/2011 7:21:31 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:31 AM

Lesser

omentum

Esophagus

Stomach

Diaphragm

Greater omentum,

gastrocolic portion

Anastomosis between

right and left gastro-

omental (epiploic)

arteries

Transverse colon appearing

in an unusual gap in the

greater omentum

Transversus

abdominis

11th costal

cartilage

10th rib

Costodiaphragmatic

recess

Gallbladder

Duodenum

Omental (epiploic)

foramen

Porta hepatis

7th rib

Liver Falciform ligament

Sadler_Chap15.indd 217

Sadler_Chap15.indd 217

8/26/2011 7:21:32 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:32 AM

218

Part II Systems-Based Embryology

with the vitelline and umbilical veins, which

form hepatic sinusoids. Liver cords differentiate

into the parenchyma (liver cells) and form

the lining of the biliary ducts. Hematopoietic

cells, Kupffer cells

, and connective tissue

cells

are derived from mesoderm of the septum

transversum.

When liver cells have invaded the entire sep-

tum transversum, so that the organ bulges cau-

dally into the abdominal cavity, mesoderm of

the septum transversum lying between the liver

and the foregut and the liver and the ventral

abdominal wall becomes membranous, forming

the lesser omentum and falciform ligament,

respectively. Together, having formed the peri-

toneal connection between the foregut and the

ventral abdominal wall, they are known as the

ventral mesentery

(Fig. 15.15).

Mesoderm on the surface of the liver dif-

ferentiates into visceral peritoneum except on

its cranial surface (Fig. 15.15B). In this region,

the liver remains in contact with the rest of the

original septum transversum. This portion of

the septum, which consists of densely packed

mesoderm, will form the central tendon of the

diaphragm

. The surface of the liver that is in

contact with the future diaphragm is never cov-

ered by peritoneum; it is the bare area of the

liver

(Fig. 15.15).

In the 10th week of development, the

weight of the liver is approximately 10% of the

total body weight. Although this may be attrib-

uted partly to the large numbers of sinusoids,

another important factor is its hematopoietic

function

. Large nests of proliferating cells,

which produce red and white blood cells, lie

between hepatic cells and walls of the vessels.

This activity gradually subsides during the last

(Figs. 15.14 and 15.15). This outgrowth, the

hepatic diverticulum

, or liver bud, consists

of rapidly proliferating cells that penetrate the

septum transversum

, that is, the mesodermal

plate between the pericardial cavity and the

stalk of the yolk sac (Figs. 15.14 and 15.15).

While hepatic cells continue to penetrate the

septum, the connection between the hepatic

diverticulum and the foregut (duodenum) nar-

rows, forming the bile duct. A small ventral

outgrowth is formed by the bile duct, and this

outgrowth gives rise to the gallbladder and

the cystic duct (Figs. 15.15). During further

development, epithelial liver cords intermingle

Parietal

peritoneum

Duodenum

Dorsal

mesoduodenum

Kidney

B

A

Pancreas

Pancreas and

duodenum in

retroperitoneal

position

Figure 15.17

Transverse sections through the region of the duodenum at various stages of development. At fi rst, the

duodenum and head of the pancreas are located in the median plane. A, but later, they swing to the right and acquire a

retroperitoneal position. B.

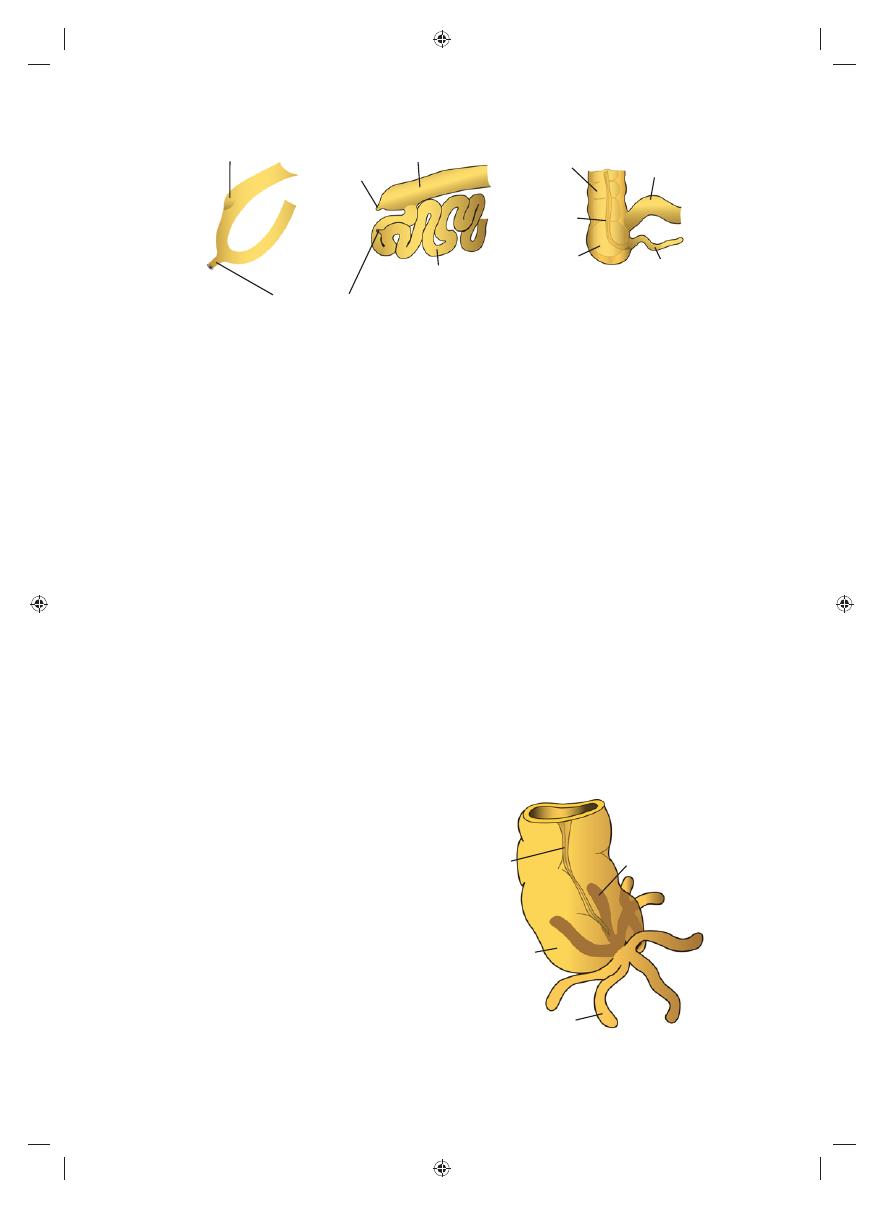

Cavity

formation

Recanalization

Solid stage

A

B

Figure 15.18

Upper portion of the duodenum showing

the solid stage. A and cavity formation. B produced by

recanalization.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 218

Sadler_Chap15.indd 218

8/26/2011 7:21:37 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:37 AM

Chapter 15 Digestive System

219

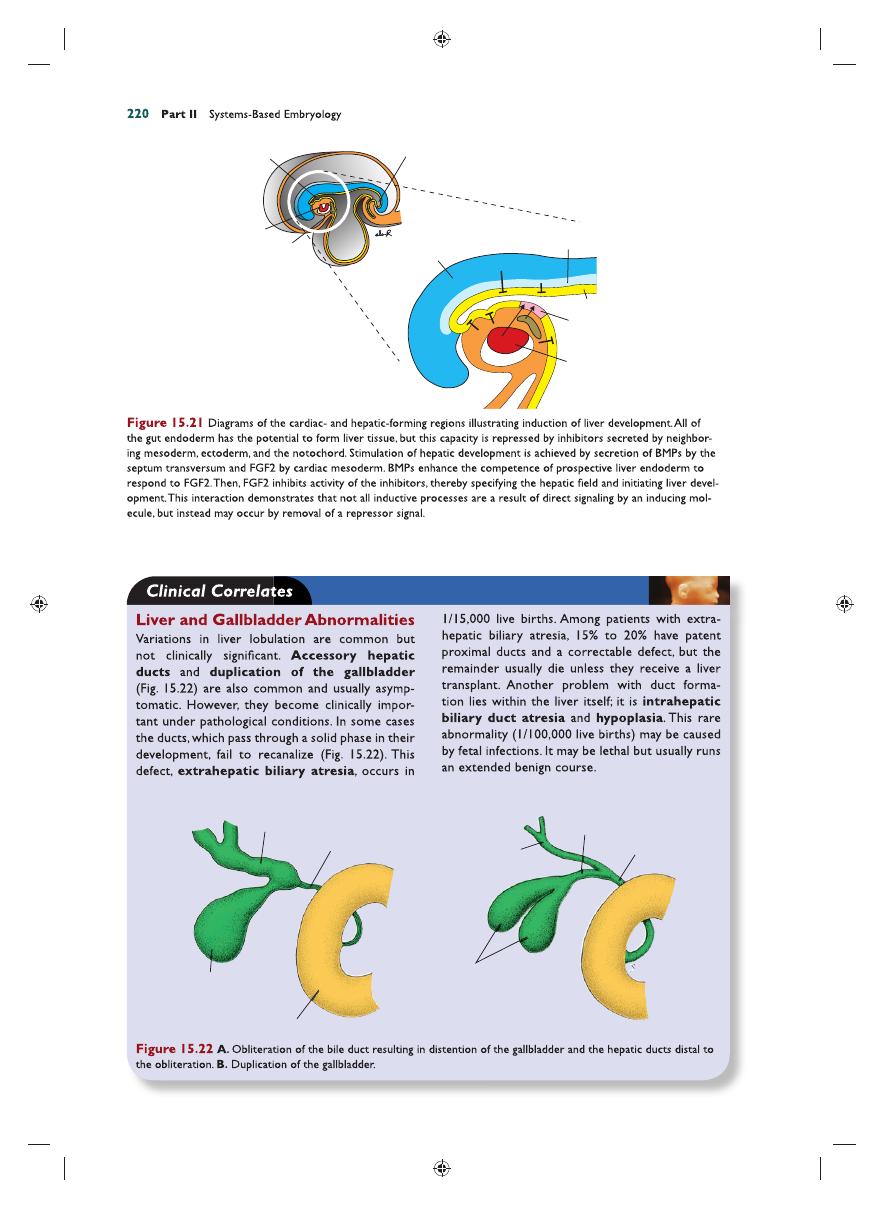

blocked by factors produced by surrounding tis-

sues, including ectoderm, noncardiac mesoderm,

and particularly the notochord (Fig. 15.21).

The action of these inhibitors is blocked in

the prospective hepatic region by fi broblast

growth factors (FGF2)

secreted by cardiac

mesoderm and by blood vessel-forming endo-

thelial cells adjacent to the gut tube at the site

of liver bud outgrowth. Thus, the cardiac meso-

derm together with neighboring vascular endo-

thelial cells “instructs” gut endoderm to express

liver-specifi c genes by inhibiting an inhibitory

factor of these same genes. Other factors par-

ticipating in this “instruction” are bone mor-

phogenetic proteins (BMPs)

secreted by the

septum transversum. BMPs appear to enhance

the competence of prospective liver endoderm

to respond to FGF2. Once this “instruction”

is received, cells in the liver fi eld differentiate

into both hepatocytes and biliary cell lineages,

a process that is at least partially regulated

by hepatocyte nuclear transcription factors

(HNF3 and

4).

2 months of intrauterine life, and only small

hematopoietic islands remain at birth. The

weight of the liver is then only 5% of the total

body weight.

Another important function of the liver

begins at approximately the 12th week, when

bile is formed by hepatic cells. Meanwhile, since

the gallbladder and cystic duct have developed

and the cystic duct has joined the hepatic duct to

form the bile duct (Fig. 15.15), bile can enter

the gastrointestinal tract. As a result, its contents

take on a dark green color. Because of positional

changes of the duodenum, the entrance of the

bile duct gradually shifts from its initial anterior

position to a posterior one, and consequently,

the bile duct passes behind the duodenum

(Figs. 15.19 and 15.20).

MOLECULAR REGULATION OF

LIVER INDUCTION

All of the foregut endoderm has the potential

to express liver-specifi c genes and to differenti-

ate into liver tissue. However, this expression is

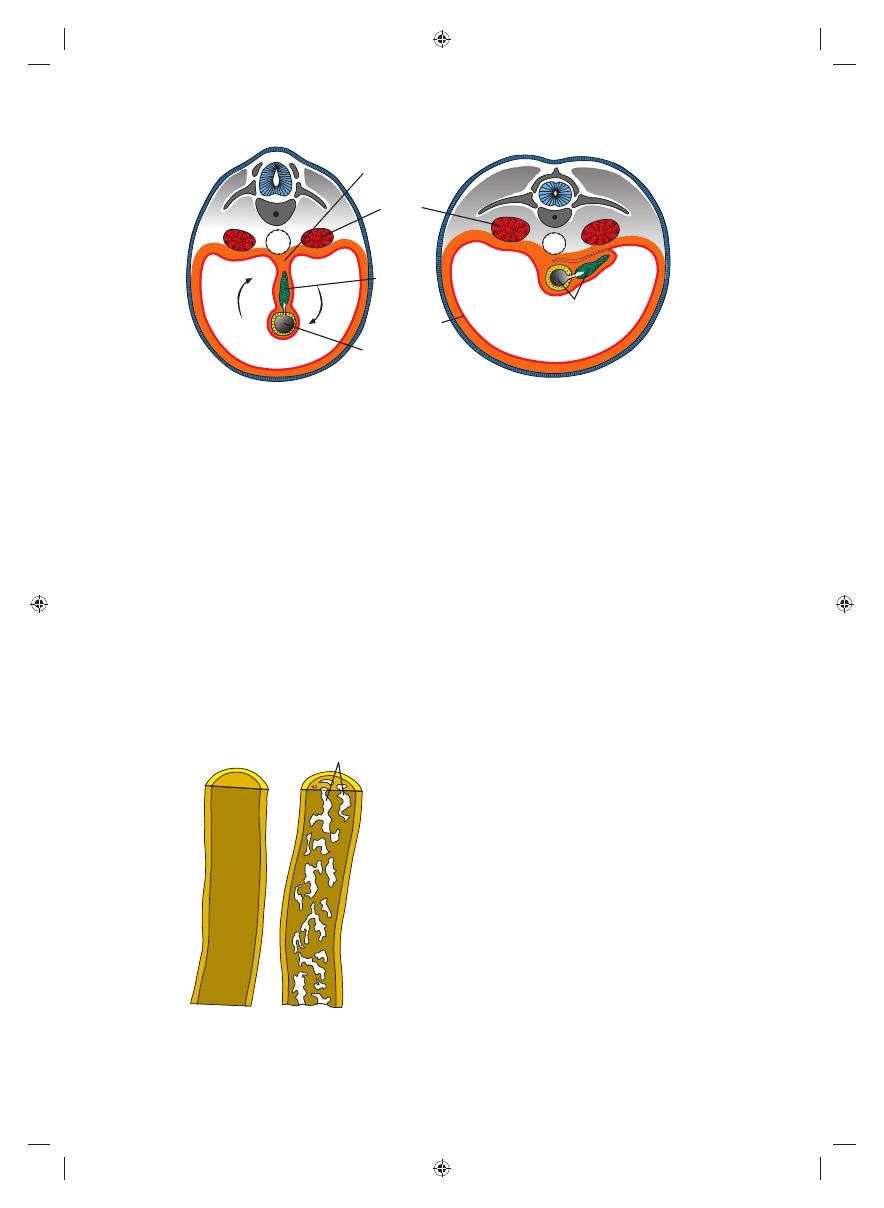

Liver bud

Gallbladder

Ventral

pancreatic bud

A

B

Ventral

pancreas

Dorsal

pancreas

Dorsal

pancreatic bud

Hepatic

duct

Cystic

duct

Bile

duct

Stomach

Figure 15.19

Stages in development of the pancreas. A. 30 days (approximately 5 mm). B. 35 days (approximately 7 mm).

Initially, the ventral pancreatic bud lies close to the liver bud, but later, it moves posteriorly around the duodenum toward

the dorsal pancreatic bud.

Bile duct

Bile

duct

Minor papilla

Major papilla

A

B

Ventral

pancreatic duct

Ventral

pancreatic duct

Accessory

pancreatic duct

Main pancreatic duct

Uncinate process

Dorsal

pancreatic duct

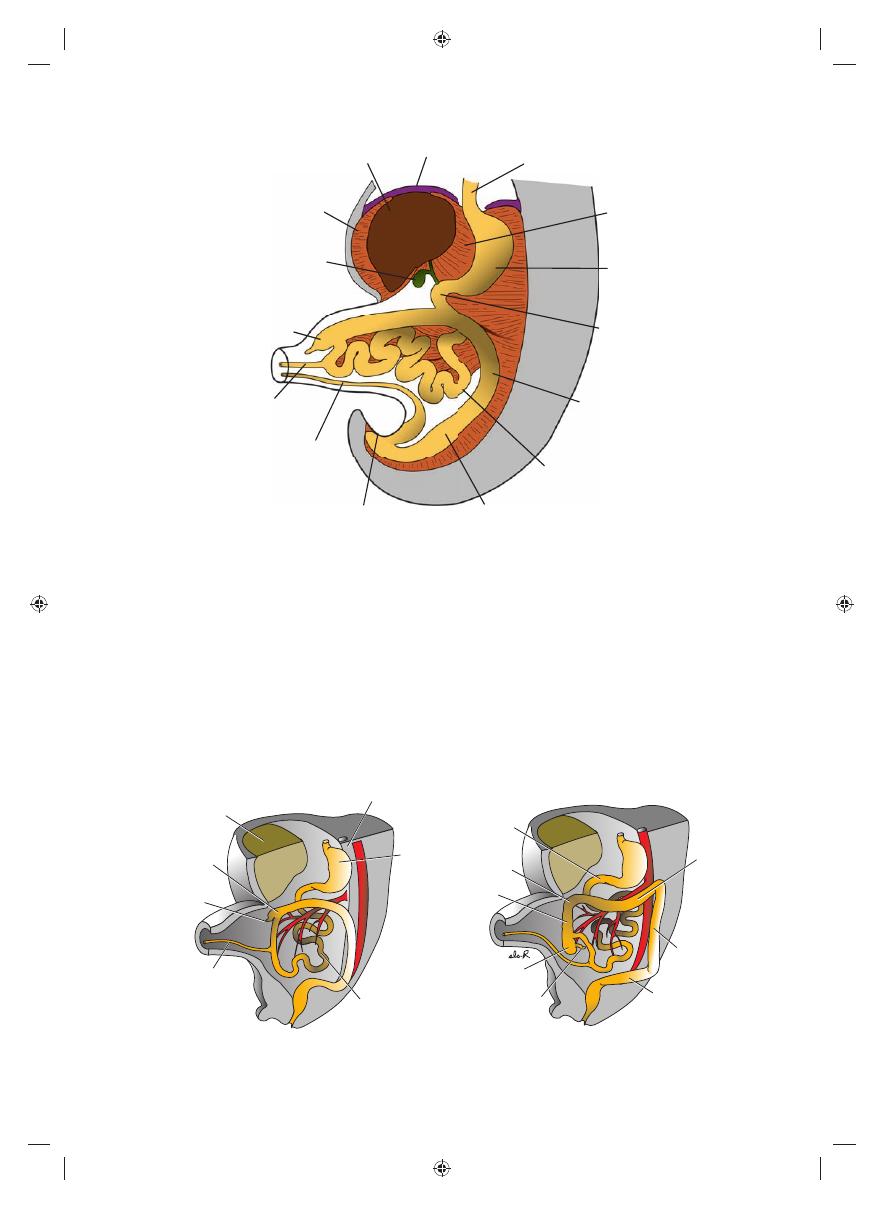

Figure 15.20

A. Pancreas during the sixth week of development. The ventral pancreatic bud is in close contact with the

dorsal pancreatic bud. B. Fusion of the pancreatic ducts. The main pancreatic duct enters the duodenum in combination with

the bile duct at the major papilla. The accessory pancreatic duct (when present) enters the duodenum at the minor papilla.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 219

Sadler_Chap15.indd 219

8/26/2011 7:21:37 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:37 AM

Endoderm

Hepatic

field

Cardiac

mesoderm

FGF

Notochord

Ectoderm

Hindgut

Heart

tube

Foregut

Septum

transversum

BMPs

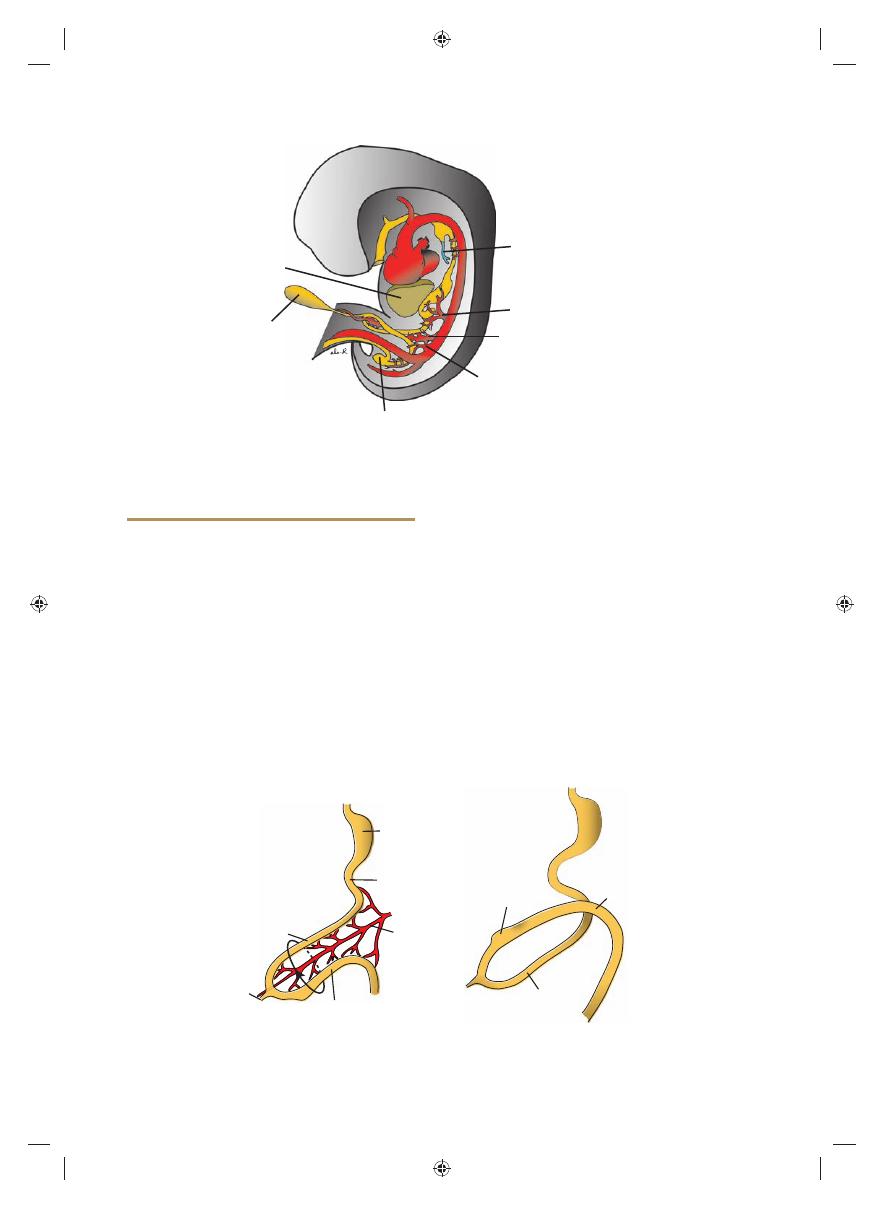

Distended

hepatic duct

Bile duct,

obliterated

Duodenal loop

Duplication of

gallbladder

Hepatic duct

Cystic duct

Bile duct

A

B

Gallbladder

Sadler_Chap15.indd 220

Sadler_Chap15.indd 220

8/26/2011 7:21:38 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:38 AM

Bile duct

Hepatic duct

Gallbladder

Ventral

pancreas

Main

pancreatic duct

Accessory pancreatic duct

Dorsal

pancreas

Stomach

Sadler_Chap15.indd 221

Sadler_Chap15.indd 221

8/26/2011 7:21:40 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:40 AM

222

Part II Systems-Based Embryology

loop

(Figs. 15.24 and 15.25). At its apex, the loop

remains in open connection with the yolk sac by

way of the narrow vitelline duct (Fig. 15.24).

The cephalic limb of the loop develops into the

distal part of the duodenum, the jejunum, and

part of the ileum. The caudal limb becomes

the lower portion of the ileum, the cecum, the

appendix, the ascending colon, and the proximal

two-thirds of the transverse colon.

Physiological Herniation

Development of the primary intestinal loop is

characterized by rapid elongation, particularly of

the cephalic limb. As a result of the rapid growth

and expansion of the liver, the abdominal cavity

temporarily becomes too small to contain all the

MIDGUT

In the 5-week embryo, the midgut is suspended

from the dorsal abdominal wall by a short mes-

entery and communicates with the yolk sac

by way of the vitelline duct or yolk stalk

(Figs. 15.1 and 15.24). In the adult, the midgut

begins immediately distal to the entrance of the

bile duct into the duodenum (Fig. 15.15) and

terminates at the junction of the proximal two-

thirds of the transverse colon with the distal third.

Over its entire length, the midgut is supplied by

the superior mesenteric artery (Fig. 15.24).

Development of the midgut is characterized

by rapid elongation of the gut and its mesentery,

resulting in formation of the primary intestinal

Celiac artery

Superior mesenteric

artery

Inferior mesenteric

artery

Cloaca

Yolk sac

Liver

Lung bud

Figure 15.24

Embryo during the sixth week of development, showing blood supply to the segments of the gut and

formation and rotation of the primary intestinal loop. The superior mesenteric artery forms the axis of this rotation and

supplies the midgut. The celiac and inferior mesenteric arteries supply the foregut and hindgut, respectively.

Transverse

colon

Small intestine

Cecal bud

Duodenum

Stomach

Superior

mesenteric

artery

Caudal limb of primary

intestinal loop

Cephalic limb

of primary

intestinal loop

Vitelline

duct

B

A

Figure 15.25

A. Primary intestinal loop before rotation (lateral view). The superior mesenteric artery forms the axis of

the loop. Arrow, counterclockwise rotation. B. Similar view as in A showing the primary intestinal loop after 180° counter-

clockwise rotation. The transverse colon passes in front of the duodenum.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 222

Sadler_Chap15.indd 222

8/26/2011 7:21:42 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:42 AM

Chapter 15 Digestive System

223

counterclockwise, and it amounts to approximately

270° when it is complete (Figs. 15.24 and 15.25).

Even during rotation, elongation of the small intes-

tinal loop continues, and the jejunum and ileum

form a number of coiled loops (Fig. 15.26). The

large intestine likewise lengthens considerably but

does not participate in the coiling phenomenon.

Rotation occurs during herniation (about 90°), as

well as during return of the intestinal loops into

the abdominal cavity (remaining 180°) (Fig. 15.27).

intestinal loops, and they enter the extraembry-

onic cavity in the umbilical cord during the sixth

week of development (physiological umbili-

cal herniation)

(Fig. 15.26).

Rotation of the Midgut

Coincident with growth in length, the primary

intestinal loop rotates around an axis formed by

the superior mesenteric artery (Fig. 15.25).

When viewed from the front, this rotation is

Liver

Diaphragm

Falciform ligament

Vitelline duct

Cecum

Gallbladder

Esophagus

Allantois

Cloacal membrane

Rectum

Lesser omentum

Stomach

Duodenum

Descending color

Jejunoileal loops

Figure 15.26

Umbilical herniation of the intestinal loops in an embryo of approximately 8 weeks (crown-rump length, 35

mm). Coiling of the small intestinal loops and formation of the cecum occur during the herniation. The fi rst 90° of rotation

occurs during herniation; the remaining 180° occurs during the return of the gut to the abdominal cavity in the third month.

Stomach

Jejunoileal

loops

Vitelline

duct

Cecal

bud

Ascending

colon

Aorta

Liver

Duodenum

Transverse

colon

Descending

colon

Ascending

colon

Hepatic

flexure

Sigmoid

Appendix

Cecum

B

A

Figure 15.27

A. Anterior view of the intestinal loops after 270° counterclockwise rotation. Note the coiling of the small

intestinal loops and the position of the cecal bud in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. B. Similar view as in A with

the intestinal loops in their fi nal position. Displacement of the cecum and appendix caudally places them in the right lower

quadrant of the abdomen.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 223

Sadler_Chap15.indd 223

8/26/2011 7:21:44 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:44 AM

224

Part II Systems-Based Embryology

peritoneum of the posterior abdominal wall

(Fig. 15.30). After fusion of these layers, the

ascending and descending colons are perma-

nently anchored in a retroperitoneal position.

The appendix, lower end of the cecum, and

sigmoid colon, however, retain their free mes-

enteries (Fig. 15.30B).

The fate of the transverse mesocolon is dif-

ferent. It fuses with the posterior wall of the

greater omentum (Fig. 15.30) but maintains its

mobility. Its line of attachment fi nally extends

from the hepatic fl exure of the ascending colon

to the splenic fl exure of the descending colon

(Fig. 15.30B).

The mesentery of the jejunoileal loops is

at fi rst continuous with that of the ascending

colon (Fig. 15.30A). When the mesentery of

the ascending mesocolon fuses with the poste-

rior abdominal wall, the mesentery of the jeju-

noileal loops obtains a new line of attachment

that extends from the area where the duodenum

becomes intraperitoneal to the ileocecal junction

(Fig. 15.30B).

Retraction of Herniated Loops

During the 10th week, herniated intestinal

loops begin to return to the abdominal cavity.

Although the factors responsible for this return

are not precisely known, it is thought that regres-

sion of the mesonephric kidney, reduced growth

of the liver, and expansion of the abdominal cav-

ity play important roles.

The proximal portion of the jejunum, the

fi rst part to reenter the abdominal cavity, comes

to lie on the left side (Fig. 15.27A). The later

returning loops gradually settle more and more

to the right. The cecal bud, which appears at

about the sixth week as a small conical dila-

tion of the caudal limb of the primary intes-

tinal loop, is the last part of the gut to reenter

the abdominal cavity. Temporarily, it lies in the

right upper quadrant directly below the right

lobe of the liver (Fig. 15.27A). From here, it

descends into the right iliac fossa, placing the

ascending colon

and hepatic fl exure on the

right side of the abdominal cavity (Fig. 15.27B).

During this process, the distal end of the cecal

bud forms a narrow diverticulum, the appen-

dix

(Fig. 15.28).

Since the appendix develops during descent

of the colon, its fi nal position frequently is pos-

terior to the cecum or colon. These positions of

the appendix are called retrocecal or retrocolic,

respectively (Fig. 15.29).

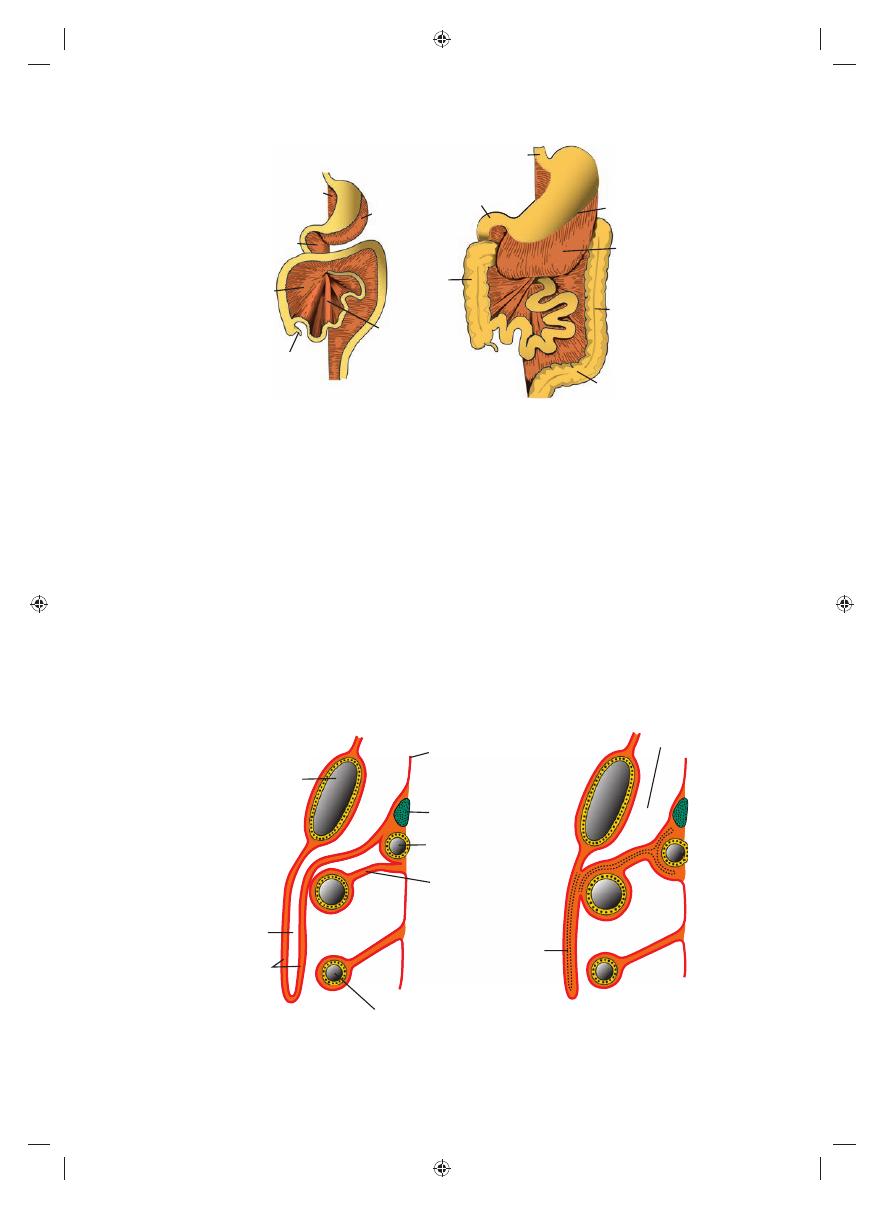

Mesenteries of the Intestinal Loops

The mesentery of the primary intestinal loop,

the mesentery proper, undergoes profound

changes with rotation and coiling of the bowel.

When the caudal limb of the loop moves to

the right side of the abdominal cavity, the dor-

sal mesentery twists around the origin of the

superior mesenteric artery

(Fig. 15.24).

Later, when the ascending and descending

portions of the colon obtain their defi nitive

positions, their mesenteries press against the

Ascending colon

Ileum

Appendix

Appendix

Cecal bud

A

B

C

Vitelline duct

Cecum

Cecum

Tenia

Jejunoileal loops

Figure 15.28

Successive stages in development of the cecum and appendix. A. 7 weeks. B. 8 weeks. C. Newborn.

Retrocecal

position of

vermiform

appendix

Tenia

libera

Cecum

Vermiform appendix

Figure 15.29

Various positions of the appendix. In about

50% of cases, the appendix is retrocecal or retrocolic.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 224

Sadler_Chap15.indd 224

8/26/2011 7:21:44 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:44 AM

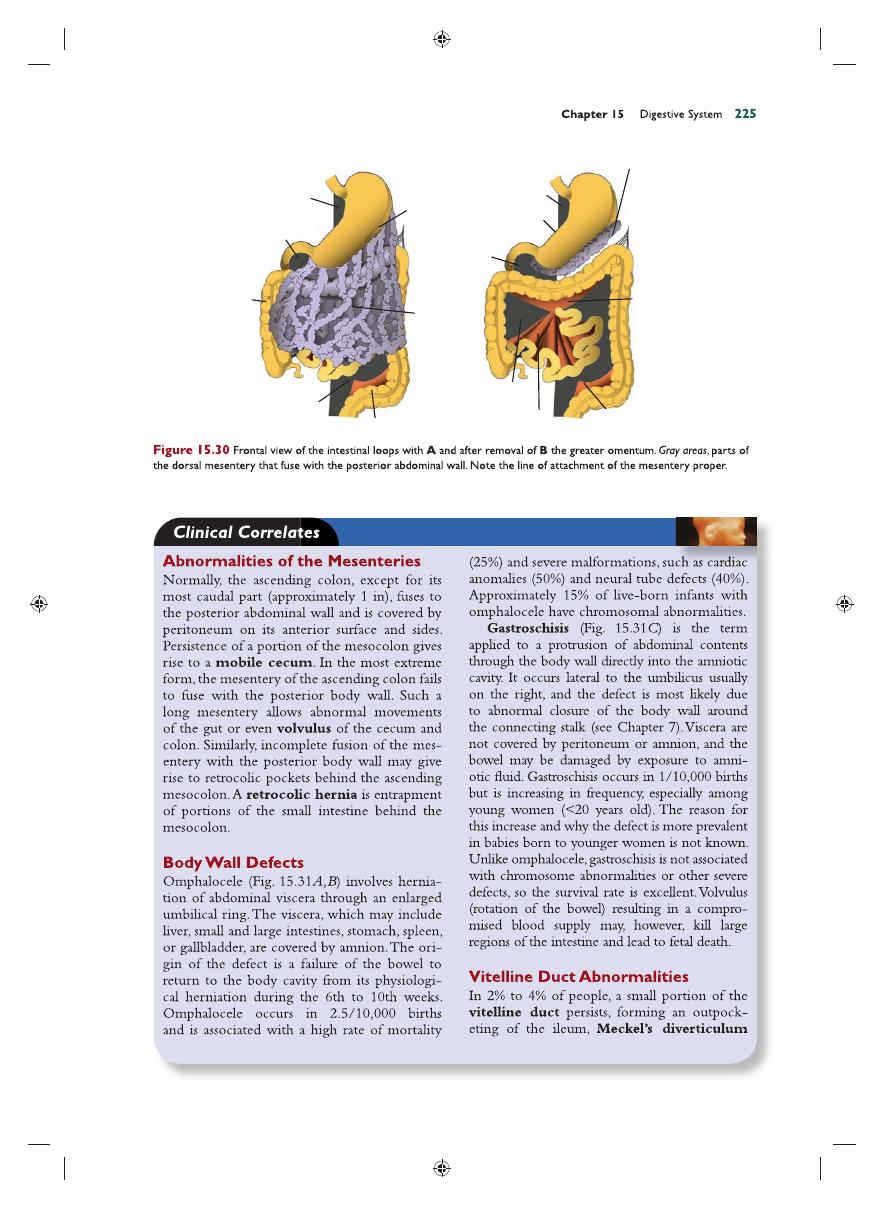

Dorsal mesoduodenum

fused with

abdominal

wall

Dorsal

mesoduodenum

fused with

posterior

abdominal

wall

Mesocolon fused with

abdominal wall

Mesocolon fused with

abdominal wall

Dorsal mesogastruim

fused with

abdominal

wall

Dorsal mesogastruim

fused with

posterior

abdominal wall

Ascending

colon

Greater

curvature

Lesser curvature

Greater

omentum

Sigmoid

Sigmoid

mesocolon

Transverse

mesocolon

Cut edge of

greater omentum

Mesentery proper

B

A

Sadler_Chap15.indd 225

Sadler_Chap15.indd 225

8/26/2011 7:21:45 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:45 AM

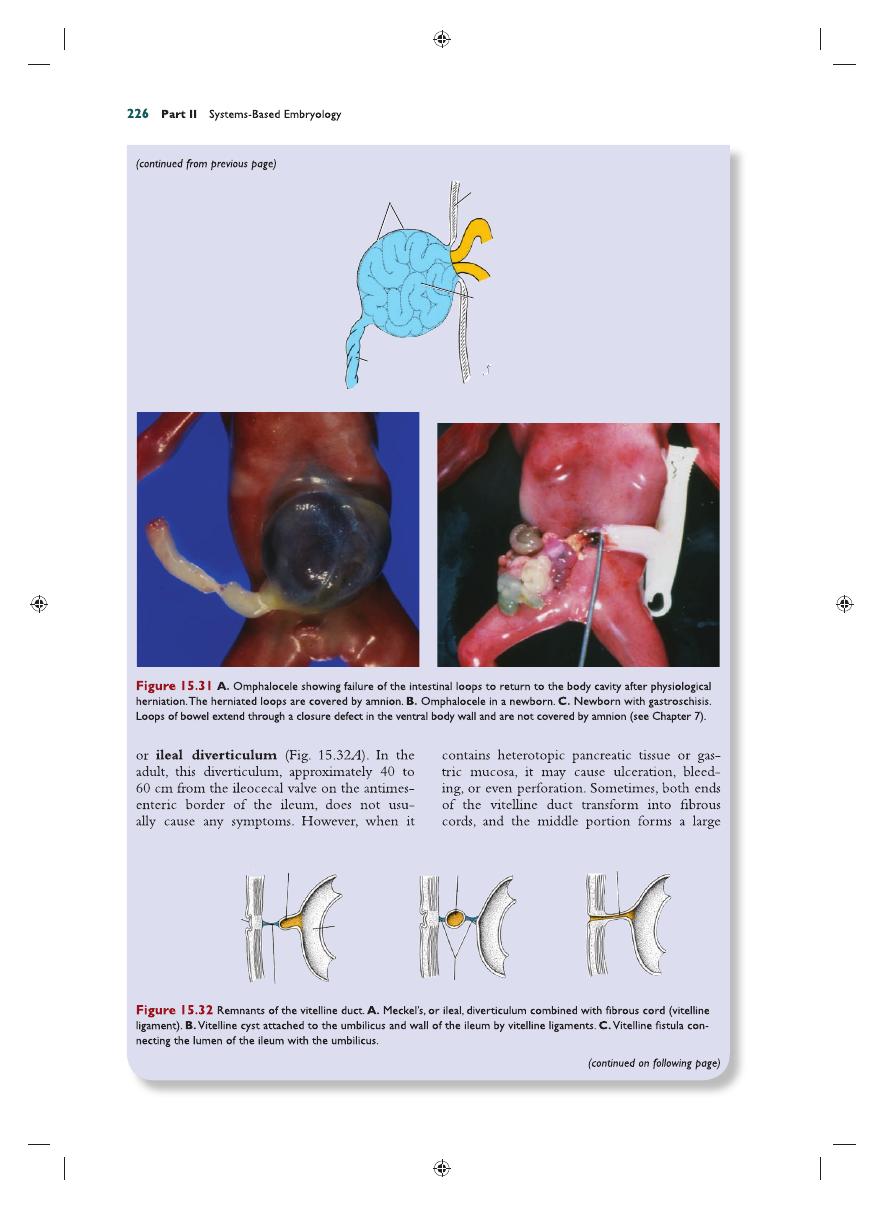

A

B

C

Vitelline ligaments

Vitelline ligaments

Vitelline cyst

Vitelline fistula

Meckel’s diverticulum

Umbilicus

Ileum

Amnion

Abdominal

wall

Intestinal

loops

Umbilical

cord

A

B

C

Sadler_Chap15.indd 226

Sadler_Chap15.indd 226

8/26/2011 7:21:47 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:47 AM

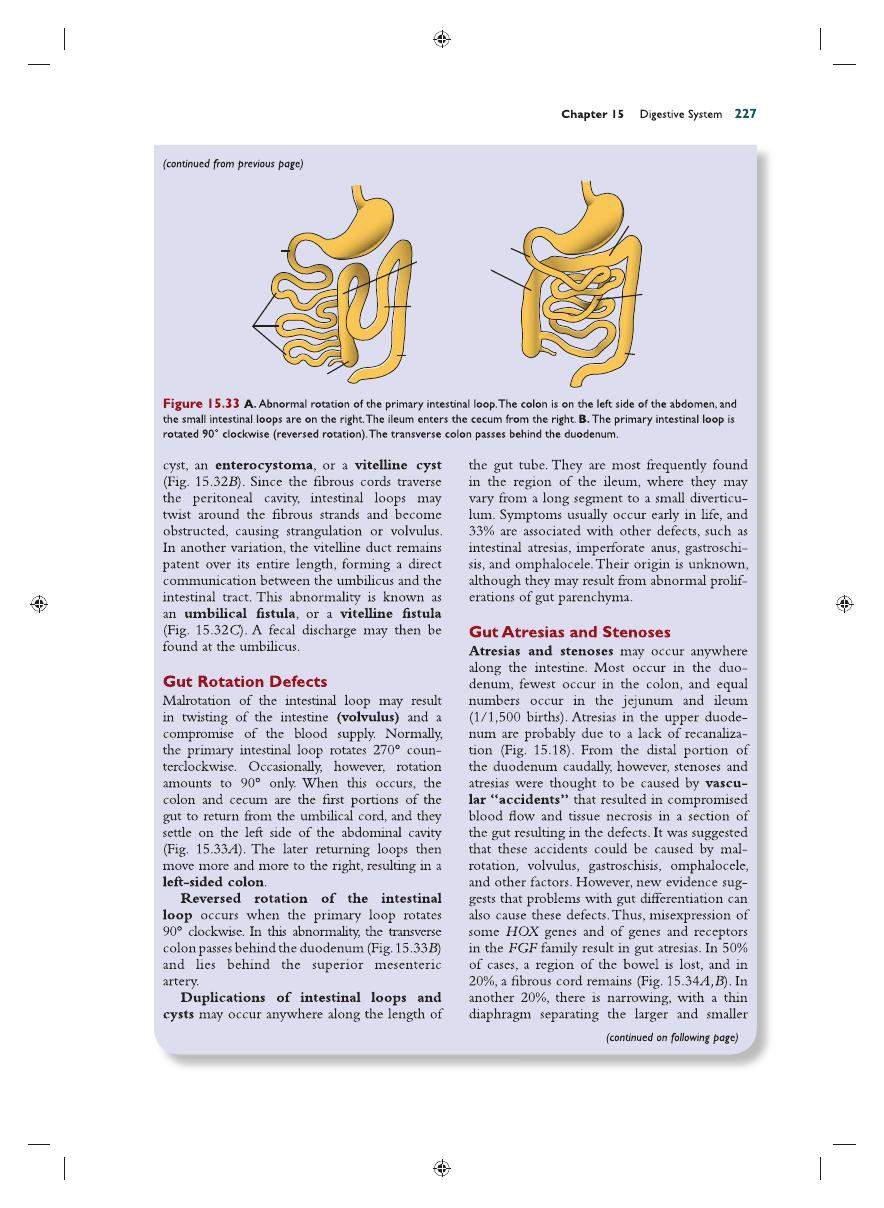

Transverse

colon

Transverse

colon

Ascending colon

Duodenum

Duodenum

Cecum

B

A

Descending

colon

Descending

colon

Jejunoileal

loops

Jejunoileal

loops

Sadler_Chap15.indd 227

Sadler_Chap15.indd 227

8/26/2011 7:21:50 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:50 AM

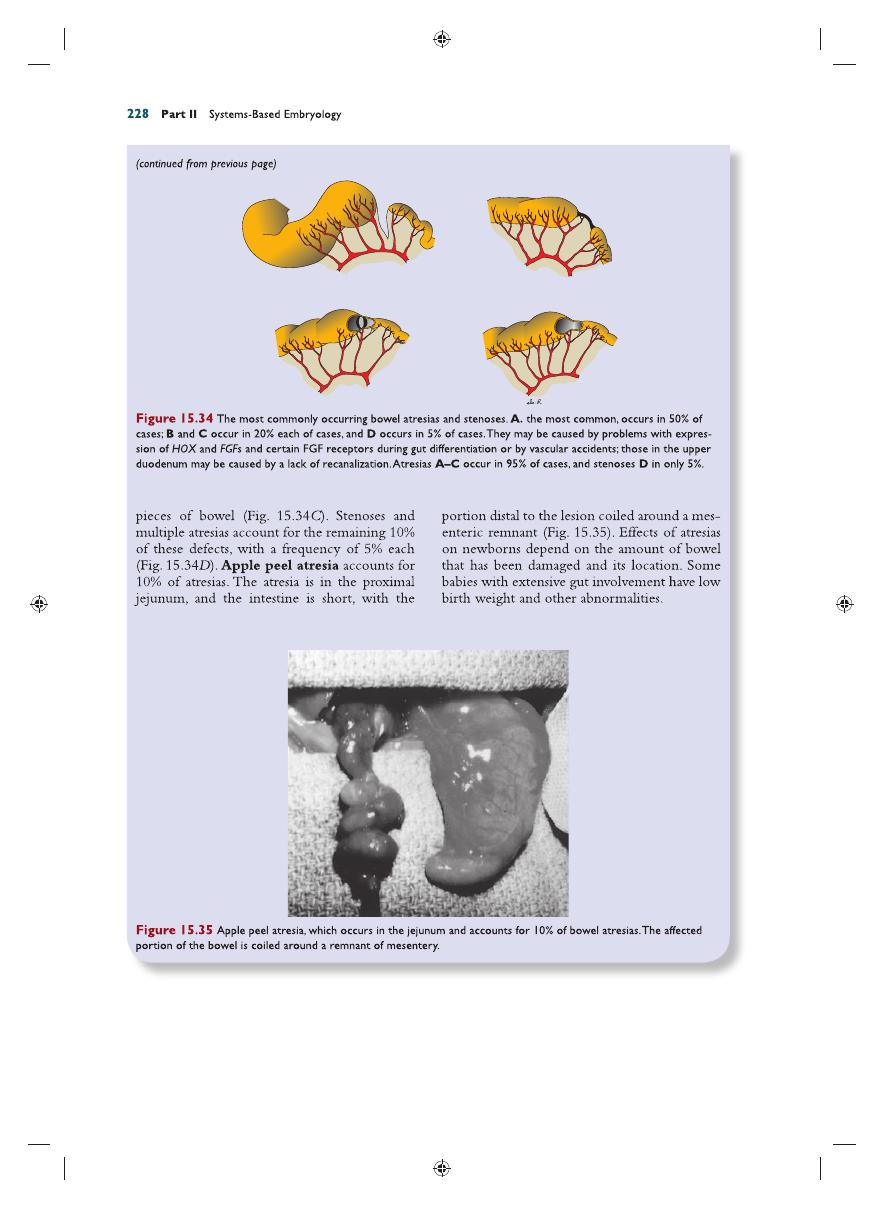

A

D

C

B

Sadler_Chap15.indd 228

Sadler_Chap15.indd 228

8/26/2011 7:21:51 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:51 AM

Chapter 15 Digestive System

229

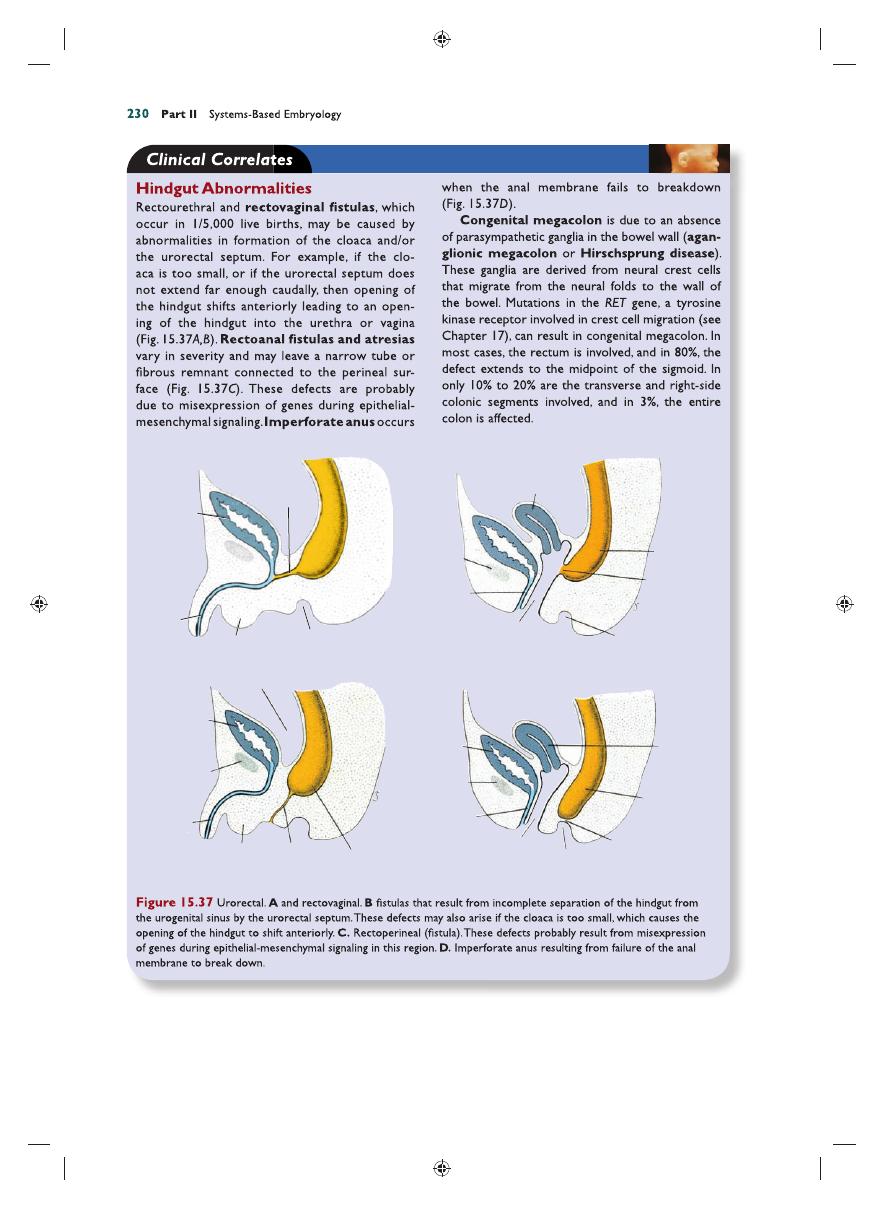

HINDGUT

The hindgut gives rise to the distal third of the

transverse colon, the descending colon, the sig-

moid, the rectum, and the upper part of the anal

canal. The endoderm of the hindgut also forms

the internal lining of the bladder and urethra (see

Chapter 16).

The terminal portion of the hindgut enters

into the posterior region of the cloaca, the

primitive anorectal canal; the allantois enters

into the anterior portion, the primitive uro-

genital sinus

(Fig 15.36A). The cloaca itself is

an endoderm-lined cavity covered at its ventral

boundary by surface ectoderm. This boundary

between the endoderm and the ectoderm forms

the cloacal membrane (Fig. 15.36). A layer of

mesoderm, the urorectal septum, separates the

region between the allantois and hindgut. This

septum is derived from the merging of meso-

derm covering the yolk sac and surrounding the

allantois (Figs. 15.1 and 15.36). As the embryo

grows and caudal folding continues, the tip of

the urorectal septum comes to lie close to the

cloacal membrane (Fig. 15.36B,C). At the end

of the seventh week, the cloacal membrane rup-

tures, creating the anal opening for the hindgut

and a ventral opening for the urogenital sinus.

Between the two, the tip of the urorectal sep-

tum forms the perineal body (Fig. 15.36C).

The upper part (two-thirds) of the anal canal

is derived from endoderm of the hindgut; the

lower part (one-third) is derived from ecto-

derm around the proctodeum (Fig. 15.36B,C).

Ectoderm in the region of the proctodeum on

the surface of part of the cloaca proliferates and

invaginates to create the anal pit (Fig. 15.37D).

Subsequently, degeneration of the cloacal

membrane

(now called the anal membrane)

establishes continuity between the upper and

lower parts of the anal canal. Since the caudal

part of the anal canal originates from ectoderm,

it is supplied by the inferior rectal arteries,

branches of the internal pudendal arteries.

However, the cranial part of the anal canal origi-

nates from endoderm and is therefore supplied

by the superior rectal artery, a continuation

of the inferior mesenteric artery, the artery

of the hindgut. The junction between the endo-

dermal and ectodermal regions of the anal canal

is delineated by the pectinate line, just below

the anal columns. At this line, the epithelium

changes from columnar to stratifi ed squamous

epithelium.

A

B

C

Cloaca

Hindgut

Cloacal

membrane

Urogenital

membrane

Anal

membrane

Anorectal canal

Perineal

body

Primitive urogenital sinus

Allantois

Urinary bladder

Urorectal

septum

Proctodeum

Figure 15.36

Cloacal region in embryos at successive stages of development. A. The hindgut enters the posterior por-

tion of the cloaca, the future anorectal canal; the allantois enters the anterior portion, the future urogenital sinus. The

urorectal septum is formed by merging of the mesoderm covering the allantois and the yolk sac (Fig. 14.1D). The cloacal

membrane, which forms the ventral boundary of the cloaca, is composed of ectoderm and endoderm. B. As caudal fold-

ing of the embryo continues, the urorectal septum moves closer to the cloacal membrane. C. Lengthening of the genital

tubercle pulls the urogenital portion of the cloaca anteriorly; breakdown of the cloacal membrane creates an opening for

the hindgut and one for the urogenital sinus. The tip of the urorectal septum forms the perineal body.

Sadler_Chap15.indd 229

Sadler_Chap15.indd 229

8/26/2011 7:21:52 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:52 AM

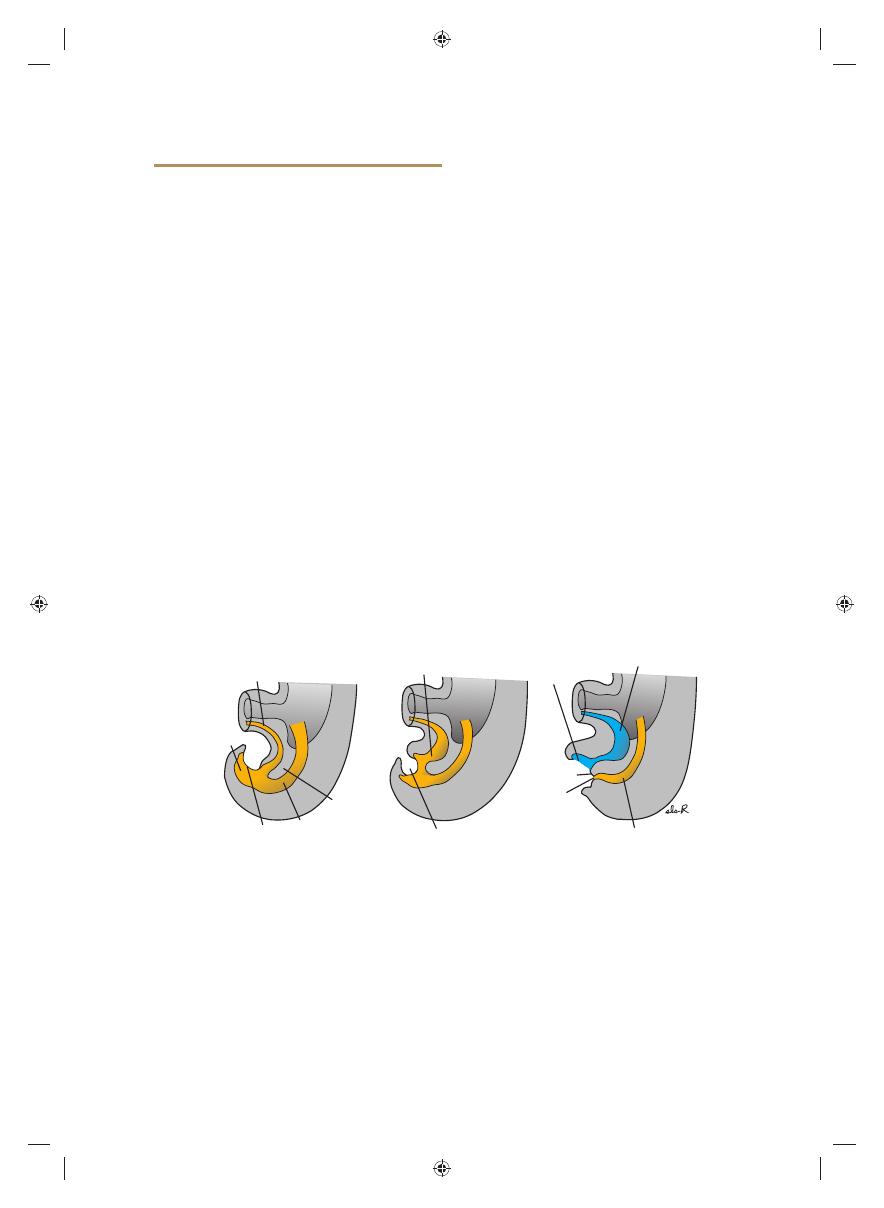

Urinary

bladder

Urethra

Urethra

Urethra

Urethra

Scrotum

Symphysis

Symphysis

Symphysis

Uterus

Uterus

Rectum

Rectum

Rectum

Rectovaginal

fistula

Rectoperineal

fistula

Peritoneal cavity

Anal pit

Anal pit

Anal membrane

Vagina

Vagina

Unrinary

bladder

Unrinary

bladder

Urorectal

fistula

Scrotum

Anal pit

A

B

C

D

Sadler_Chap15.indd 230

Sadler_Chap15.indd 230

8/26/2011 7:21:52 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:52 AM

Chapter 15 Digestive System

231

duct. During the sixth week, the loop grows so

rapidly that it protrudes into the umbilical cord

(physiological herniation) (Fig. 15.26). During

the 10th week, it returns into the abdominal

cavity. While these processes are occurring, the

midgut loop rotates 270° counterclockwise (Fig.

15.27). Remnants of the vitelline duct, failure

of the midgut to return to the abdominal cavity,

malrotation, stenosis, and duplication of parts of

the gut are common abnormalities.

The hindgut gives rise to the region from the

distal third of the transverse colon to the upper part

of the anal canal; the distal part of the anal canal

originates from ectoderm. The hindgut enters the

posterior region of the cloaca (future anorectal

canal), and the allantois enters the anterior region

(future urogenital sinus). The urorectal septum

will divide the two regions (Fig. 15.36) and break-

down of the cloacal membrane covering this area

will provide communication to the exterior for

the anus and urogenital sinus. Abnormalities in the

size of the posterior region of the cloaca shift the

entrance of the anus anteriorly, causing rectovaginal

and rectourethral fi stulas and atresias (Fig. 15.37).

The anal canal itself is derived from endoderm

(cranial part) and ectoderm (caudal part). The

caudal part is formed by invaginating ectoderm

around the proctodeum. Vascular supply to the

anal canal refl ects its dual origin. Thus, the cranial

part is supplied by the superior rectal artery

from the inferior mesenteric artery, the artery of

the hindgut, whereas the caudal part is supplied

by the inferior rectal artery, a branch of the

internal pudendal artery.

Problems to Solve

1.

Prenatal ultrasound showed polyhydram-

nios at 36 weeks, and at birth, the infant had

excessive fl uids in its mouth and diffi culty

breathing. What birth defect might cause

these conditions?

2.

Prenatal ultrasound at 20 weeks revealed a

midline mass that appeared to contain intes-

tines and was membrane bound. What diag-

nosis would you make, and what would be

the prognosis for this infant?

3.

At birth, a baby girl has meconium in her

vagina and no anal opening. What type of

birth defect does she have, and what was its

embryological origin?

Summary

The epithelium of the digestive system and the

parenchyma of its derivatives originate in the

endoderm; connective tissue, muscular com-

ponents, and peritoneal components originate

in the mesoderm. Different regions of the gut

tube such as the esophagus, stomach, duodenum,

etc. are specifi ed by a RA gradient that causes

transcription factors unique to each region to be

expressed (Fig. 15.2A). Then, differentiation of

the gut and its derivatives depends upon recip-

rocal interactions between the gut endoderm

(epithelium) and its surrounding mesoderm (an

epithelial-mesenchymal interaction). HOX genes

in the mesoderm are induced by SHH secreted

by gut endoderm and regulate the craniocaudal

organization of the gut and its derivatives. The gut

system extends from the oropharyngeal mem-

brane to the cloacal membrane (Fig. 15.5) and is

divided into the pharyngeal gut, foregut, midgut,

and hindgut. The pharyngeal gut gives rise to the

pharynx and related glands (see Chapter 17).

The foregut gives rise to the esophagus, the tra-

chea and lung buds, the stomach, and the duodenum

proximal to the entrance of the bile duct. In addi-

tion, the liver, pancreas, and biliary apparatus develop

as outgrowths of the endodermal epithelium of the

upper part of the duodenum (Fig. 15.15). Since the

upper part of the foregut is divided by a septum

(the tracheoesophageal septum) into the esophagus

posteriorly and the trachea and lung buds anteri-

orly, deviation of the septum may result in abnor-

mal openings between the trachea and esophagus.

The epithelial liver cords and biliary system grow-

ing out into the septum transversum (Fig. 15.15)

differentiate into parenchyma. Hematopoietic cells

(present in the liver in greater numbers before birth

than afterward), the Kupffer cells, and connective

tissue cells originate in the mesoderm. The pancreas

develops from a ventral bud and a dorsal bud that

later fuse to form the defi nitive pancreas (Figs. 15.19

and 15.20). Sometimes, the two parts surround the

duodenum (annular pancreas), causing constriction

of the gut (Fig. 15.23).

The midgut forms the primary intestinal

loop (Fig. 15.24), gives rise to the duodenum dis-

tal to the entrance of the bile duct, and continues

to the junction of the proximal two-thirds of the

transverse colon with the distal third. At its apex,

the primary loop remains temporarily in open

connection with the yolk sac through the vitelline

Sadler_Chap15.indd 231

Sadler_Chap15.indd 231

8/26/2011 7:21:55 AM

8/26/2011 7:21:55 AM