Disorders of altered energy balanceUnder-nutrition Starvation and famine

Dheyaa Kadhim Al-Waeli - MD, FICMS, MSc. (Endo.)Assistant professor: University of Thi-Qar, College of medicine , Department of Medicine

Adult Endocrinologist: Thi-Qar Specialized Daibetes Endocrine and Metabolism Center (TDEMC)

Thi-Qar Internist Association

E-mail: dheyaaalwaeli@yahoo.com

Email: dhiaa.alwaeli@fdemc.iq

ORCID iD:http://orcid.org/ 0000-0001-8738-2205

L 3

The World Health Organisation (WHO) reports that chronic under-nutrition is responsible for more than half of all childhood deaths worldwide.

Starvation is manifest as marasmus (malnutrition with marked muscle wasting) or, when additive complications such as oxidative stress come into play, malnourished children can develop kwashiorkor (malnutrition with oedema).

marasmus

kwashiorkorGrowth retardation is due to deficiencies of key nutrients (protein, zinc, potassium, phosphate and sulphur).

In adults, starvation is the result of chronic sustained negative energy (calorie) balance.

Clinical features of severe under-nutrition in adults

• Weight loss• Thirst, craving for food, weakness and feeling cold

• Nocturia, amenorrhoea or impotence

• Lax, pale, dry skin with loss of turgor and, occasionally, pigmented patches

Cold and cyanosed extremities, pressure sores

• Hair thinning or loss (except in adolescents)

• Muscle-wasting, best demonstrated by the loss of the temporalis and periscapular muscles and reduced mid-arm circumference

• Loss of subcutaneous fat, reflected in reduced skinfold thickness and mid-arm circumference

• Hypothermia, bradycardia, hypotension and small heart

• Oedema, which may be present without hypoalbuminaemia (‘famine oedema’)

• Distended abdomen with diarrhea

• Diminished tendon jerks

• Apathy, loss of initiative, depression, introversion, aggression if food is nearby

• Susceptibility to infections

Investigations

In a famine, laboratory investigations may be impractical but will show that• Plasma free fatty acids are increased and there is ketosis and a mild metabolic acidosis.

• Plasma glucose is low but albumin concentration is often maintained because the liver still functions normally.

• Insulin secretion is diminished, glucagon and cortisol tend to increase, and reverse T3 replaces normal triiodothyronine.

Infections associated with starvation

• Gastroenteritis and Gram-negative sepsis

• Respiratory infections, especially bronchopneumonia

• Certain viral diseases, especially measles and herpes simplex

• Tuberculosis

• Streptococcal and staphylococcal skin infections

• Helminthic infestations

Management

Whether in a famine or in wasting secondary to disease, the severity of under-nutrition is graded according to BMI.People with mild starvation are in no danger; those with moderate starvation need extra feeding; and those who are severely underweight need hospital care.

In severe starvation, there is atrophy of the intestinal epithelium and of the exocrine pancreas, and the bile is dilute.

It is critical for the condition to be managed by experts. When food becomes available, it should be given by mouth in small, frequent amounts at first, using a suitable formula preparation .

During refeeding, a weight gain of 5% body weight per month indicates satisfactory progress..

Other care is supportive and includes:-

• Attention to the skin

• Adequate hydration

• Treatment of infections and

• Careful monitoring of body temperature, since thermoregulation may be impaired.

Refeeding syndrome

In severely malnourished individuals, attempts at rapid correction of malnutrition switch the body from a reliance on fat to carbohydrate metabolism.Release of insulin is triggered, shifting potassium, phosphate and magnesium into cells (with water following the osmotic gradient) and causing potentially fatal shifts of fluids and electrolytes from the extracellular to the intracellular compartment. Rapid depletion of (already low) thiamin exacerbates the condition.

Release of insulin

shifting potassium, phosphate and magnesium into cells

Clinical features include nausea, vomiting, muscle weakness, seizures, respiratory depression, cardiac arrest and sudden death.

The risks of refeeding are greatest in those who are most malnourished (especially chronic alcoholics), but even those who have gone without food for 5 days can be at risk and restitution of feeding should always be done slowly, with careful monitoring of serum potassium, phosphate and magnesium in the first 3–5 days

Lines of management ( according to severity ) include :-

1. Oral nutritional supplements

Poor appetite, immobility, poor dentition or even being kept ‘nil by mouth’ for hospital procedures all contribute to weight loss. As a first step, patients should be encouraged and helped to eat an adequate amount of normal food.Where swallow and intestinal function remain intact, the simplest form of assisted nutrition is the use of oral nutritional supplements.

Most branded products are nutritionally complete (fortified with the daily requirements of vitamins, minerals and trace elements).

2. Enteral feeding

Where swallowing or food ingestion is impaired but intestinal function remains intact, more invasive forms of assisted feeding may be necessary. Enteral tube feeding is usually the intervention of choice. In enteral feeding, nutrition is delivered to and absorbed by the functioning intestine. Delivery usually means bypassing the mouth and oesophagus (or sometimes the stomach and proximal small bowel) by means of a feeding tube (naso-enteral, gastrostomy or jejunostomy feeding). There are a number of theoretical advantages to enteral, as opposed to parenteral feeding.Advantages of enteral feeding over parenteral feeding:-

• • Preservation of intestinal mucosal architecture, gut associated lymphoid tissue, and hepatic and pulmonary immune function• • Reduced levels of systemic inflammation and hyperglycaemia

• • Interference with pathogenicity of gut micro-organisms.

• • Fewer episodes of infection

• • Reduced cost

• • Earlier return to intestinal function

• • Reduced length of hospital stay.

Routes of access

• Nasogastric tube feeding• Gastrostomy feeding.

• Post-pyloric feeding

Diarrhoea related to enteral feeding (Factors contributing to diarrhoea)

• Fibre-free feed may reduce short-chain fatty acid production in colon

• Fat malabsorption

• Inappropriate osmotic load

• Pre-existing primary gut problem (e.g. lactose intolerance)

• Infection

Management

• Often responds well to a fibre-containing feed or a switch to an

alternative feed

• Simple anti diarrhoeal agents (e.g. loperamide) can be very effective

Parenteral nutrition

This is usually reserved for clinical situations where the absorptive functioning of the intestine is severely impaired.In parenteral feeding, nutrition is delivered directly into a large-diameter systemic vein, completely bypassing the intestine and portal venous system.

As well as being more invasive, more expensive and less physiological than the enteral route, parenteral nutrition is associated with many more complications, mainly infective and metabolic (disturbances of electrolytes, hyperglycaemia).

To minimize risk to the patient, there should be Strict adherence to:-

• Aseptic practice in handling catheters• Careful monitoring of clinical (pulse, blood pressure and temperature) and

• Biochemical (urea, electrolytes, glucose and liver function tests) parameters.

Intravenous catheter complications

• Insertion (pneumothorax, haemothorax, arterial puncture)• Catheter infection (sepsis, discitis, pulmonary or cerebral abscess)

• Central venous thrombosis

Metabolic complications

• Refeeding syndrome

• Electrolyte imbalance

•Hyperglycaemia

•Hyperalimentation

•Fluid overload

• Hepatic steatosis/fibrosis/cirrhosis

Complications of parenteral nutrition

The parenteral route may be indicated for:-

• Patients who are malnourished or at risk of becoming so• who have an inadequate or unsafe oral intake and a poorly functioning or non-functioning or perforated intestine or an intestine that cannot be accessed by tube feeding.

• In practice, it is most often required in acutely ill patients with multi-organ failure or in severely under-nourished patients undergoing surgery.

It may offer a benefit over oral or enteral feeding prior to surgery in those who are severely malnourished when other routes of feeding have been inadequate.

Parenteral nutrition following surgery should be reserved for when enteral nutrition is not tolerated or feasible or where complications (especially sepsis) impair gastrointestinal function, such that oral or enteral feeding is not possible for at least 7 days.

How monitor patient with parenteral nutrition ??

Intestinal failure (‘short bowel syndrome’)

Intestinal failure (IF) is defined as a:-reduction in the function of the gut below the minimum necessary for the absorption of macronutrients and/or water and electrolytes such that intravenous supplementation is required to support health and/or growth.

The term can be used only when there is both:

• a major reduction in absorptive capacity and• an absolute need for intravenous fluid support.

IF can be further classified according to its onset, metabolic consequences and expected outcome.

• Type 1 IF: an acute-onset, usually self-limiting condition with few long-term sequelae.

It is most often seen following abdominal surgery or in the context of critical illness.

Intravenous support may be required for a few days to weeks.

• Type 2 IF: far less common. The onset is also usually acute, following some intra-abdominal catastrophic event (ischaemia, volvulus, trauma or perioperative complication).

Septic and metabolic problems are seen, along with complex nutritional issues.

It requires multidisciplinary input (nursing, dietetic, medical, biochemical, surgical, radiological and microbiological) and support may be necessary for weeks to months.

Type 3 IF:

a chronic condition in which patients are metabolically stable but intravenous support is required over months to years.It may or may not be reversible

Causes :-

• short bowel syndrome• chronic intestinal dysmotility

• chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction

The severity of the physiological upset correlates well with how much functioning intestine remains (rather than how much has been removed).

Causes of short bowel syndrome in adults

• Mesenteric ischaemia• Post-operative complications

• Crohn’s disease

• Trauma

• Neoplasia

• Radiation enteritis

Management of short bowel patients (and ‘high-output’ stoma)

1. Accurate charting of fluid intake and losses• Vital: oral intake determines stool volume and should be restricted rather than encouraged

2. Dehydration and hyponatraemia

• Must first be corrected intravenously to restore circulating volume and reduce thirst

• Stool volume should be minimised and any ongoing fluid imbalance between oral intake and stool losses replenished intravenously

3. Measures to reduce stool volume losses

• Restrict oral fluid intake to ≤ 500 mL/24 hrs• Give a further 1000 mL oral fluid as oral rehydration solution containing 90–120 mmol Na/L (St Mark’s solution or Glucodrate, Nestlé)

• Slow intestinal transit (to maximise opportunities for absorption): Loperamide, codeine phosphate

• Reduce volume of intestinal secretions: Gastric acid: omeprazole 20 mg/day orally Other secretions: octreotide 50–100 μg 3 times daily by subcutaneous injection

4. Measures to increase absorption

• Teduglutide (a recombinant glucagon-like peptide 2) significantly reduces requirements for intravenous fluid and nutritional supportMicronutrients, minerals and their diseases

Micronutrients, minerals and their diseasesVitamins

Vitamins are organic substances with key roles in certain metabolic pathways, and are categorized into those that are:-

• Fat-soluble (vitamins A, D, E and K) and those that are

• Water-soluble (vitamins of the B complex group and vitamin C).

Nutrition in pregnancy and lactation

• Energy requirements: increased in both mother and fetus but can be met through reduced maternal energy expenditure.• Micronutrient requirements: adaptive mechanisms ensure increased uptake of minerals in pregnancy, but extra increments of some are required during lactation.

.

Additional increments of some vitamins are recommended during pregnancy and lactation:

Vitamin A: for growth and maintenance of the fetus, and to provide some reserve (important in some countries to prevent blindness associated with vitamin A deficiency). Teratogenic in excessive amounts.Vitamin D: to ensure bone and dental development in the infant. Higher incidences of hypocalcaemia, hypoparathyroidisim and defective dental enamel have been seen in infants of women not taking vitamin D supplements at > 50° latitude.

Folate: taken pre-conceptually and during the first trimester, reduces the incidence of neural tube defects by 70%.

Vitamin B12: in lactation only.

Thiamin: to meet increased fetal energy demands. Riboflavin: to meet extra demands.

Niacin: in lactation only.

Vitamin C: for the last trimester to maintain maternal stores as fetal demands increase.

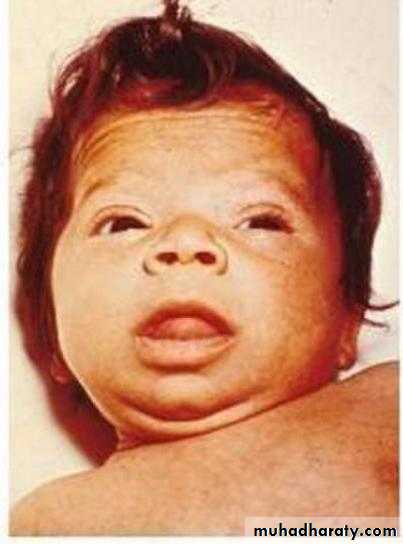

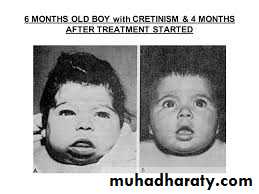

Iodine: in countries with high consumption of staple foods (e.g. brassicas, maize, bamboo shoots) that contain goitrogens (thiocyanates or perchlorates) that interfere with iodine uptake, supplements prevent infants being born with cretinism

Darker-skinned individuals living at higher latitude, and those who cover up or do not go outside are at increased risk of vitamin D deficiency due to inadequate sunlight exposure.

Dietary supplements are recommended for these ‘at-risk’ groups. Some nutrient deficiencies are induced by diseases or drugs. Deficiencies of fat-soluble vitamins are seen in conditions of fat malabsorption.

Gastrointestinal disorders that may be associated with malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins:-

• Biliary obstruction

• Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency

• Coeliac disease

• Ileal inflammation or resection

Fat-soluble vitamins

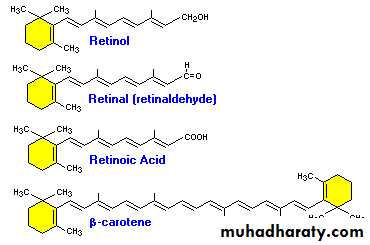

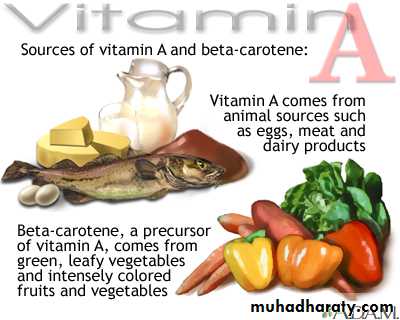

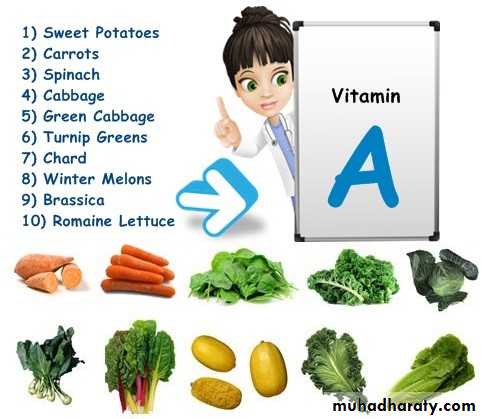

Vitamin A (retinol)Pre-formed retinol is found only in foods of animal origin.

Vitamin A can also be derived from carotenes, which are present in green and coloured vegetables and some fruits.

Carotenes provide most of the total vitamin A in the UK and constitute the only supply in vegans.

Vitamin A does not occur in plants, but many plants contain carotenoids such as beta-carotene that can be converted to vitamin A within the intestine and other tissues.

Retinol is converted to several other important molecules: 1. 11-cis-retinaldehyde is part of the photoreceptor complex in rods of the retina

2. Retinoic acid induces differentiation of epithelial cells by binding to specific nuclear receptors, which induce responsive genes. In vitamin A deficiency, mucus-secreting cells are replaced by keratin-producing cells.

3. Retinoids are necessary for normal growth, fetal development, fertility, haematopoiesis and immune function.

Globally, the most important consequence of vitamin A deficiency is irreversible blindness in young children. Asia is most notably affected and the problem is being addressed through widespread vitamin A supplementation programmes.

Adults are not usually at risk ?????

because liver stores can supply vitamin A when foods containing vitamin A are unavailable.

Early deficiency causes impaired adaptation to the dark (night blindness). Keratinisation of the cornea (xerophthalmia) gives rise to characteristic Bitot’s spots and progresses to keratomalacia, with corneal ulceration, scarring and irreversible blindness .

In countries where vitamin A deficiency is endemic, pregnant women should be advised to eat dark green, leafy vegetables and yellow fruits (to build up stores of retinol in the fetal liver), and infants should be fed the same.

Eye signs of vitamin A deficiency. A. Bitot’s spots in xerophthalmia, showing the white triangular plaques (arrows). B. Keratomalacia in a 14-month-old child. There is liquefactive necrosis affecting the greater part of the cornea, with typical sparing of the superior aspect.

The WHO is according high priority to prevention in communities where xerophthalmia occurs, giving single prophylactic oral doses of 60 mg retinyl palmitate (providing 200 000 U retinol) to pre-school children.

This also reduces mortality from gastroenteritis and respiratory infections.

Repeated moderate or high doses of retinol can cause:-

liver damage, hyperostosis and teratogenicity.Women in countries where deficiency is not endemic are therefore advised not to take vitamin A supplements in pregnancy.

Retinol intake may also be restricted in those at risk of osteoporosis.

Acute overdose leads to nausea and headache, increased intracranial pressure and skin desquamation.

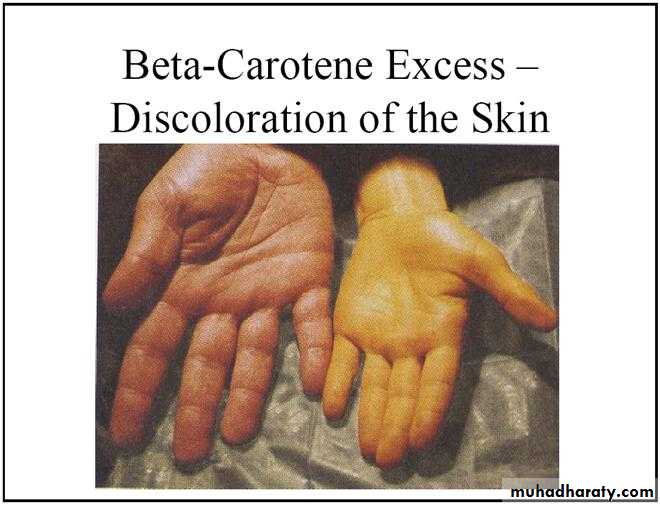

Excessive intake of carotene can cause pigmentation of the skin (hypercarotenosis); this gradually fades when intake is reduced.