Hypermia And Congestion

Congestion

In this system we will discuss the following:

•

Hyperemia and Congestion

•

Hemorrhage

•

Edema

•

Thrombosis

•

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

•

Embolism

Infarction

•

Shock

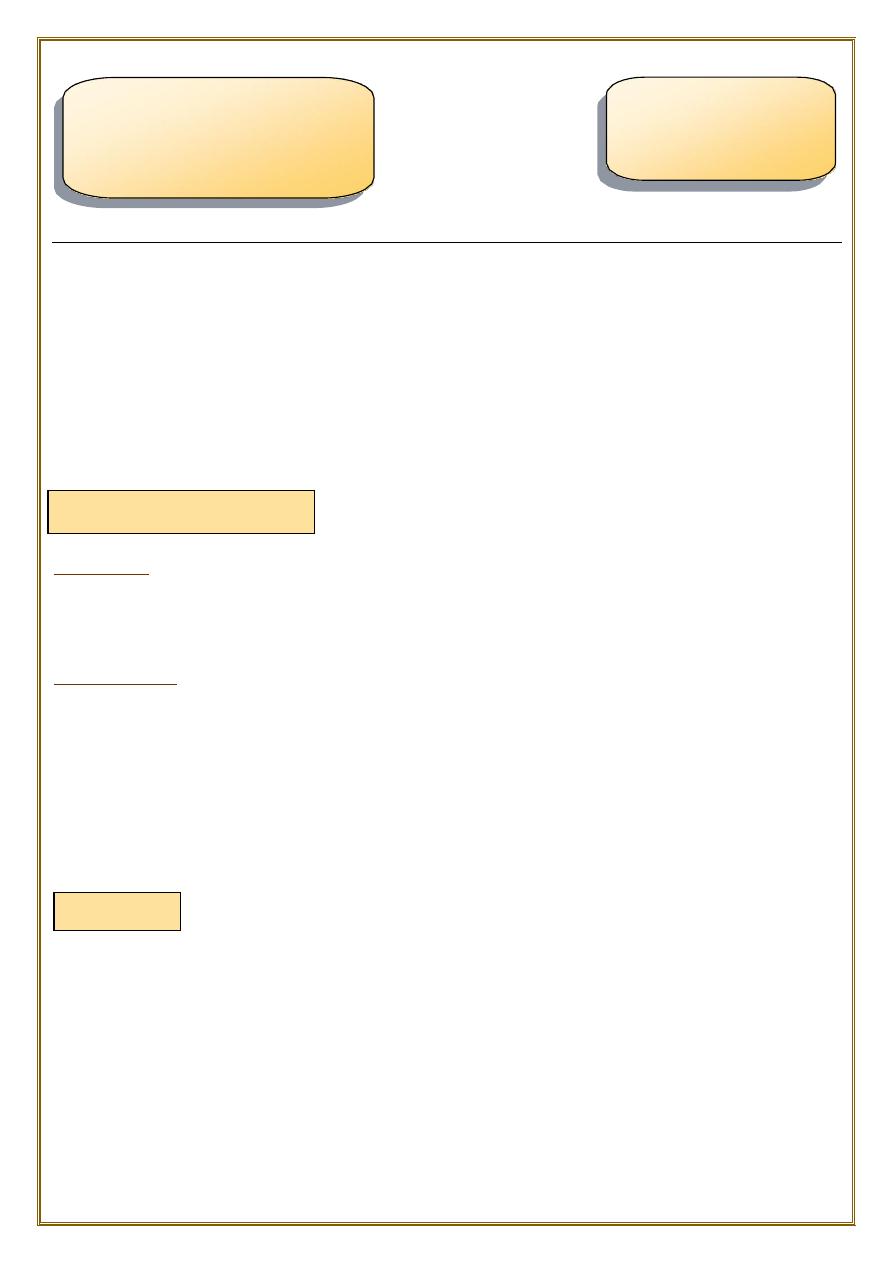

Definition

both of them can be defined as a local increase in volume of blood in a particular

tissue.

Hyperemia

It is an

active

process resulting from

arteriolar dilation

and increased blood inflow,

as occurs at sites of:

•

exercising skeletal muscle.

•

or acute inflammation.

♦

Hyperemic tissues are

redder

than normal because of engorgement with oxygenated

blood.

Congestion is a passive process resulting from impaired outflow of venous blood from a

tissue.

It can occur:

•

systemically, as in cardiac failure,

•

or locally as a consequence of an isolated venous obstruction.

♦

Congested tissues have an abnormal

blue-red

color (cyanosis) that stems from the

accumulation of

deoxygenated

hemoglobin in the affected area.

Patho

Assis. Prof.

Dr.Maha Shakir

Pdf by Qamar Saad

Hemodynamic Disorders,

Thromboembolism,

and Shock

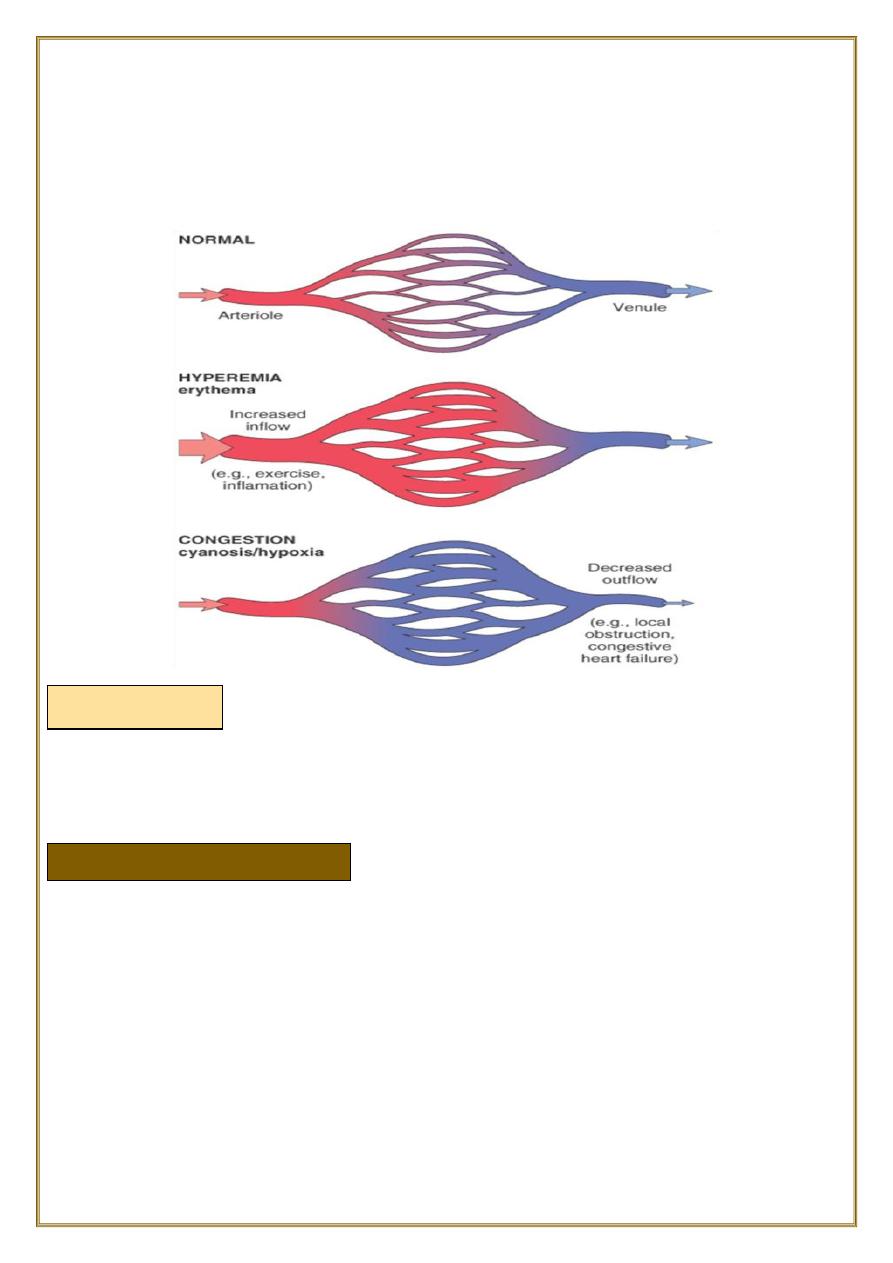

MORPHOLOGY

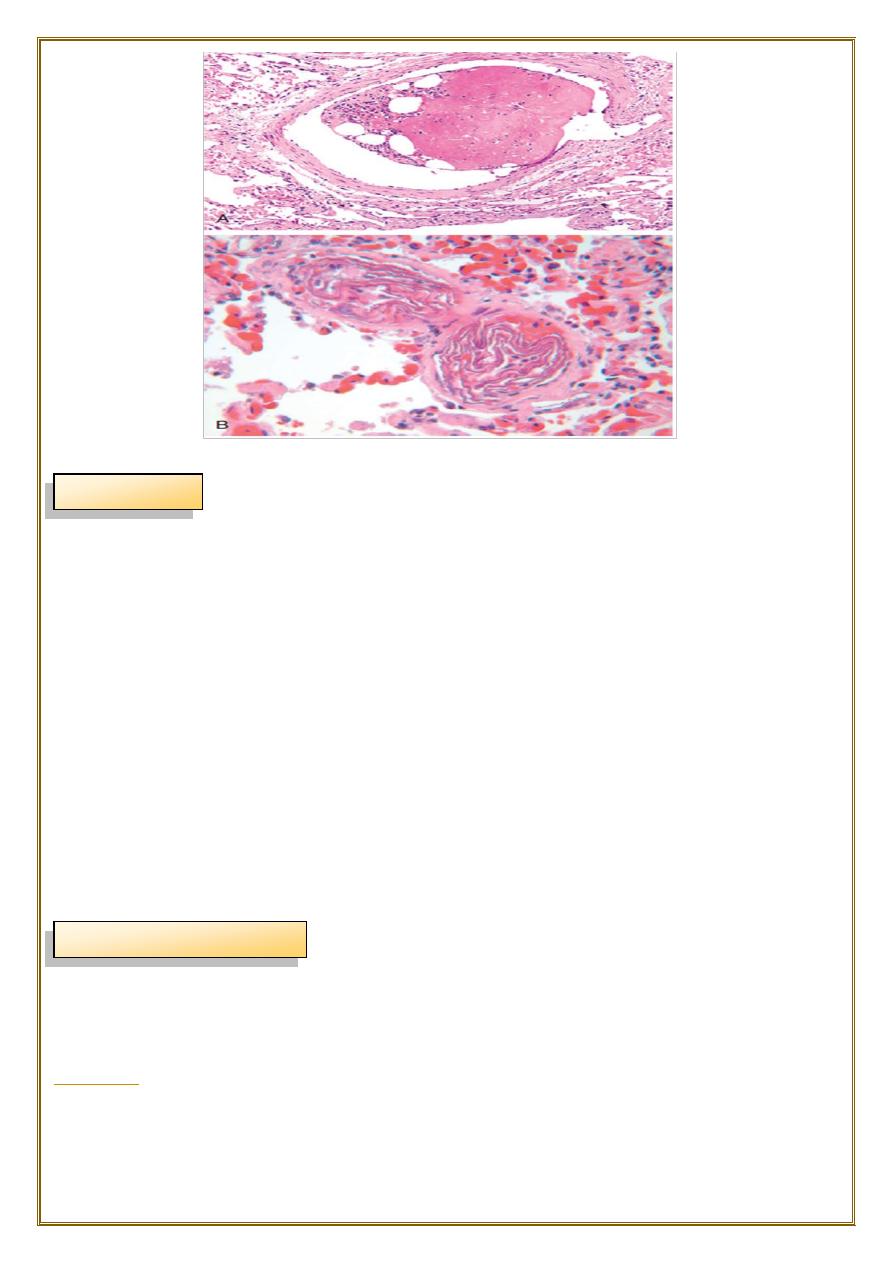

a) Pulmonary congestion:

♦ In long-standing chronic congestion, inadequate tissue perfusion and persistent

hypoxia may lead to:

•

parenchymal cell death.

•

secondary tissue fibrosis.

•

the elevated intravascular pressures may cause edema or sometimes rupture

capillaries forming focal hemorrhage.

Cut surfaces of hyperemic or congested tissues

•

feel wet and

•

typically ooze blood.

•

Acute

•

chronic

1.

Acute pulmonary congestion:

•

Alveolar capillaries engorged with blood

•

variable degrees of alveolar septal edema and intraalveolar hemorrhage.

2.

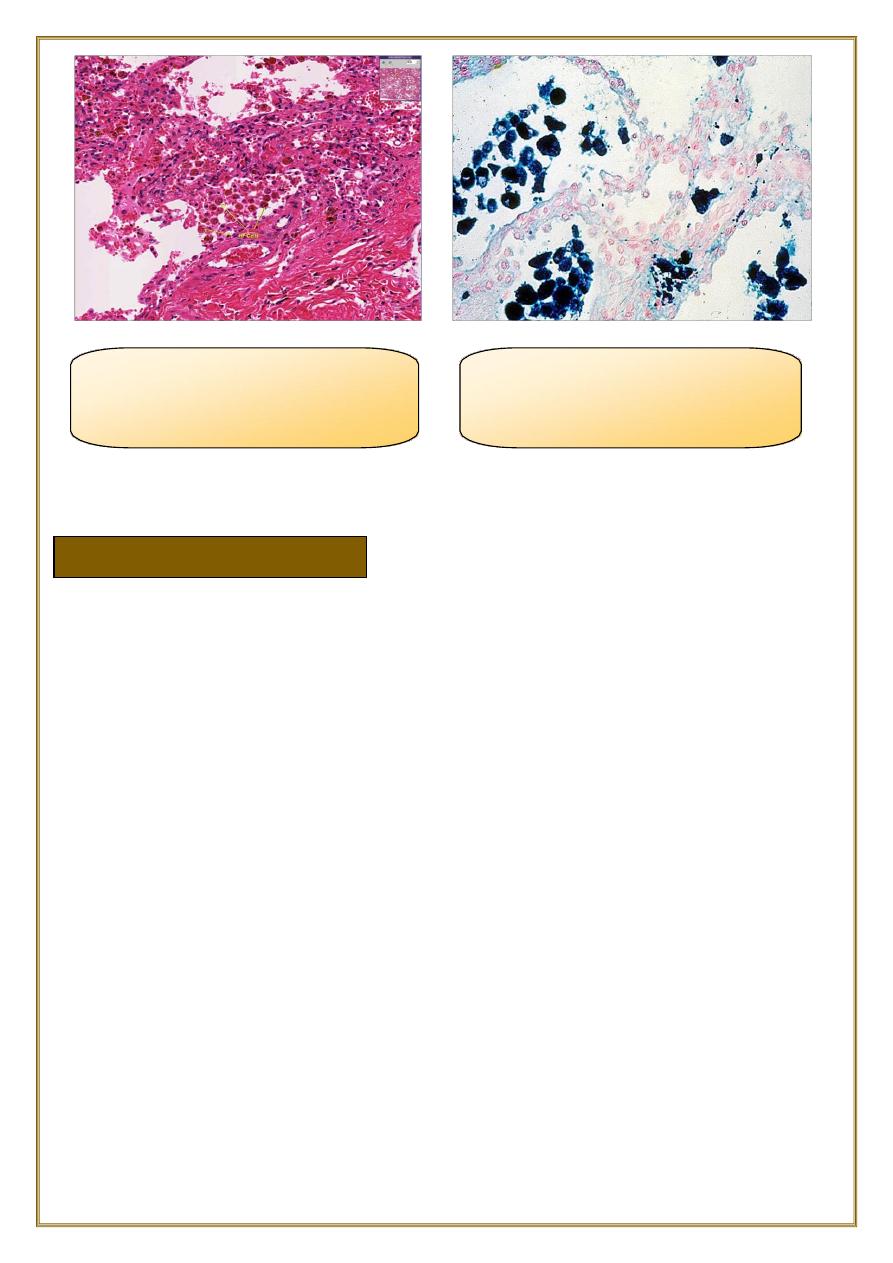

Chronic pulmonary congestion:

•

Thickened & fibrotic septa

•

Alveolar spaces contain hemosiderin-laden macrophages (“heart failure cells”)

derived from phagocytosed red cells.

Fig; Lung, acute pulmonary congestion.

fig:Lung, chronic passive congestions: surface The

lung has a red-brown color due to accumulation of

hemosiderin from extravasated erythrocytes. Fibrosis

causes the cut edges to stand up rather than collapse.

fig: left :normal lung.

right:acute passive hyperemia/congestion, lung

fig:chronic passive

hyperemia/congestion, lung:

heart failure cells

Fig:Special stain for

haemosiderin (prusian blue) for

heart failure cells

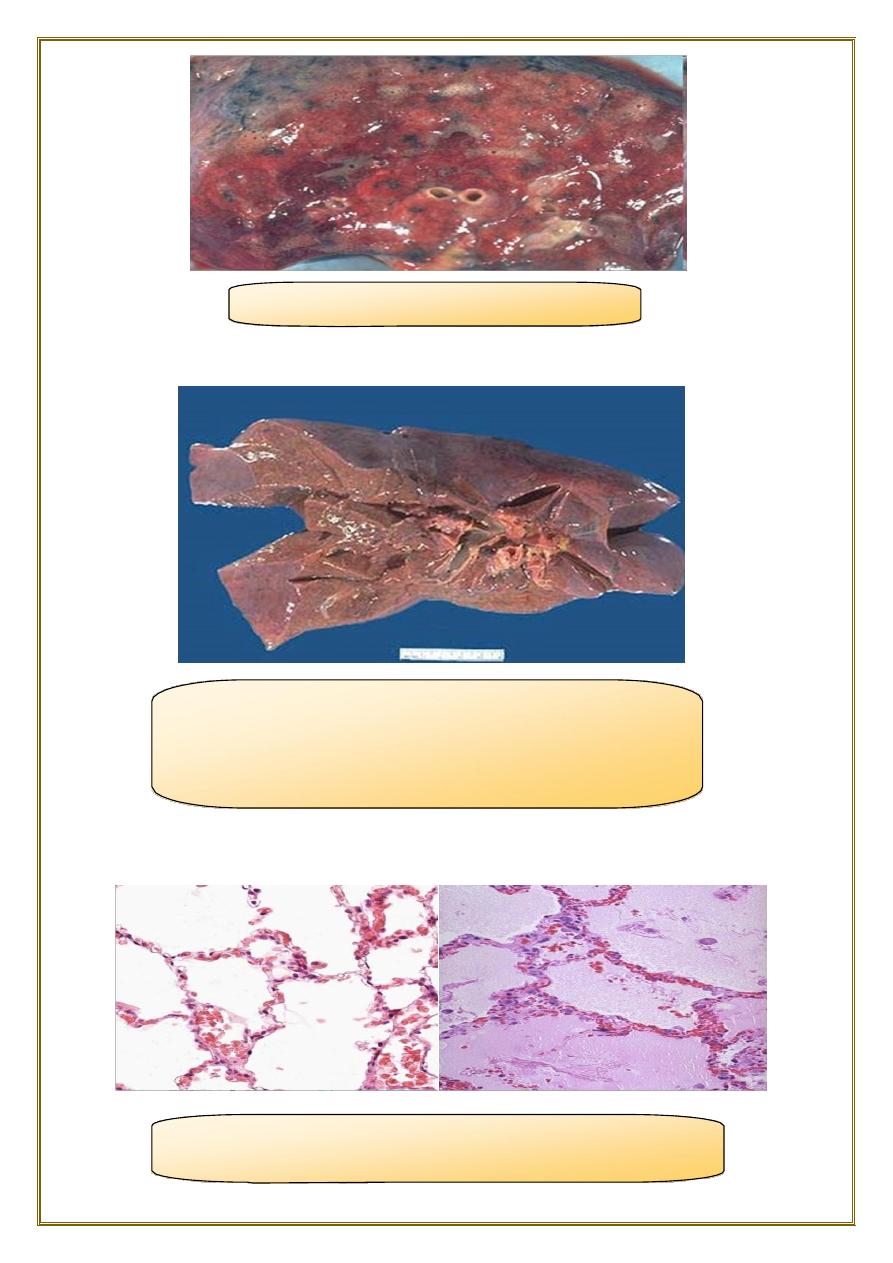

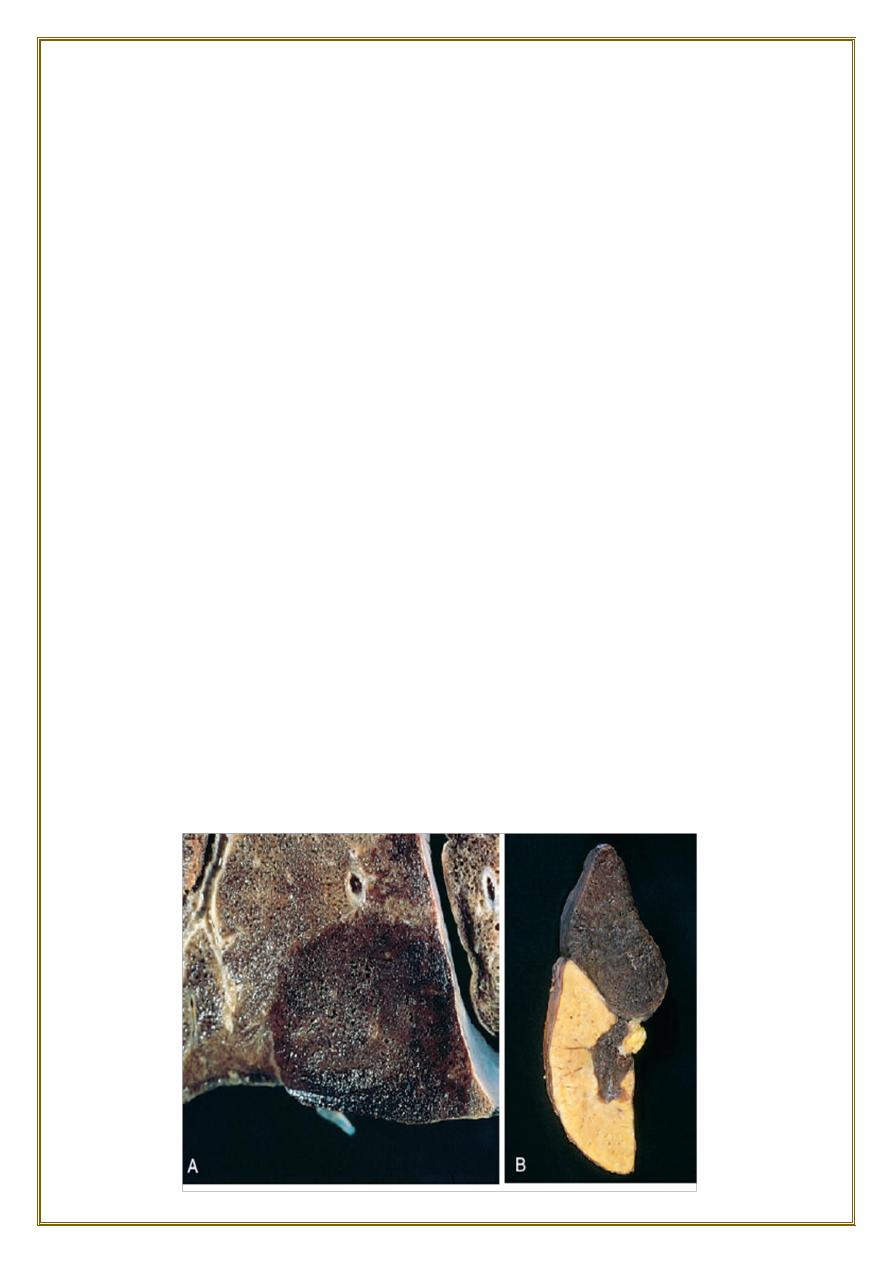

b) Hepatic congestion

1-

Acute hepatic congestion:

•

the central vein and sinusoids are distended with blood,

•

and there may even be necrosis of centrally located hepatocytes.

•

The periportal hepatocytes, better oxygenated???WHY

because of their proximity to

hepatic arterioles

, experience less severe hypoxia and

may develop only reversible

fatty change

.

2-

Chronic passive congestion of liver:

Gross examination

•

the central regions of the hepatic lobules, viewed, are red-brown and slightly

depressed.

•

the surrounding zones of uncongested tan, sometimes fatty, liver (nutmeg liver).

Microscopic findings

•

centrilobular hepatocyte necrosis.

•

hemorrhage.

•

hemosiderin-laden macrophages.

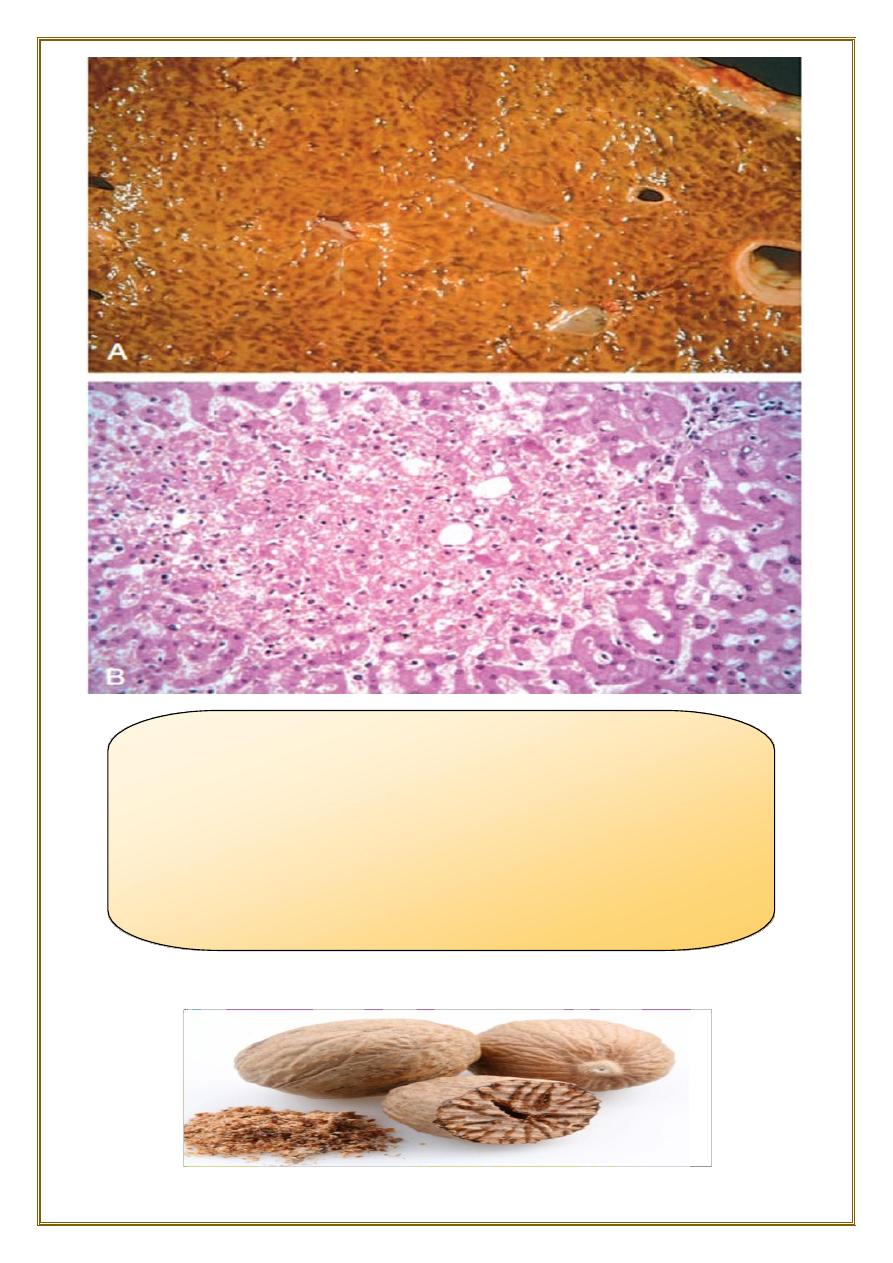

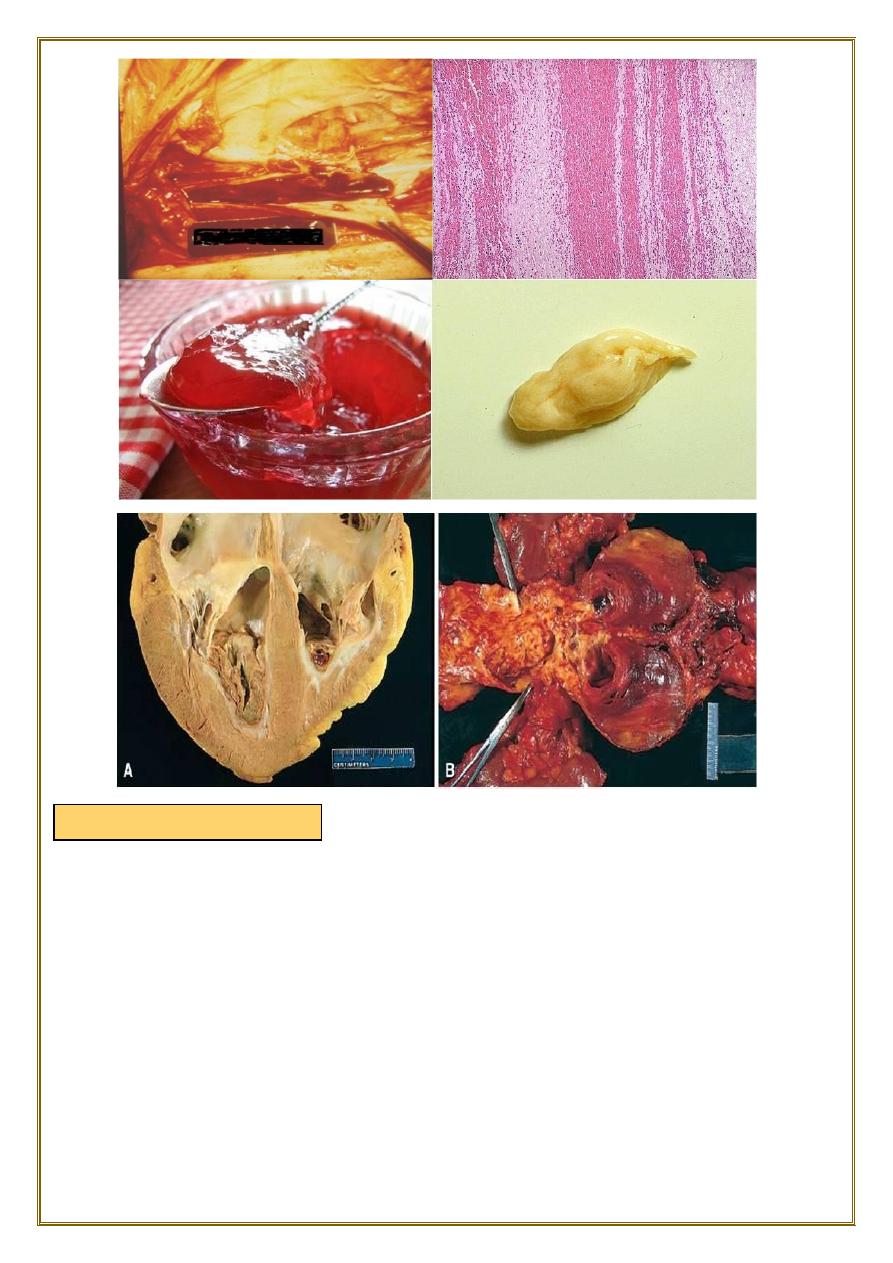

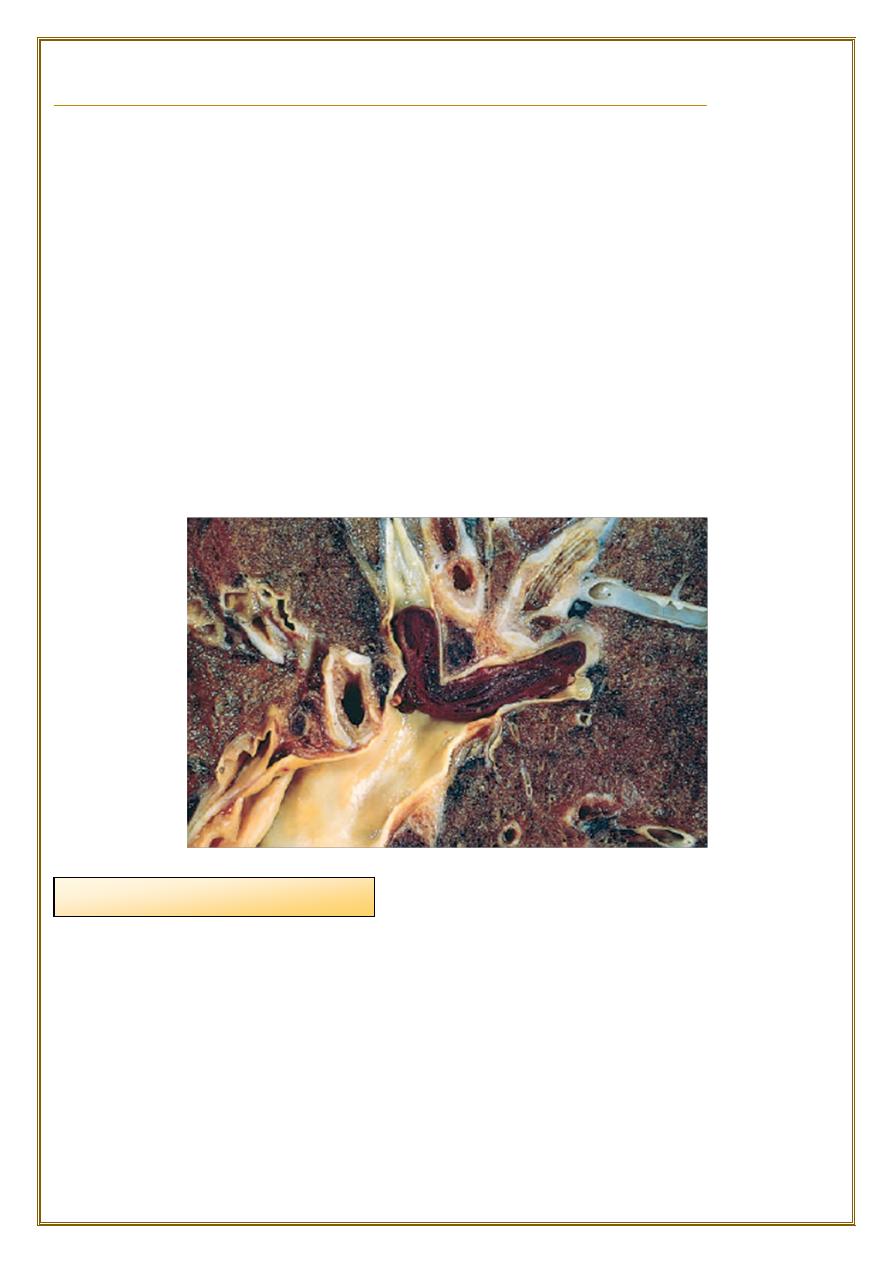

Fig. Liver with chronic passive congestion and hemorrhagic

necrosis.

(A) In this autopsy specimen, central areas are red and slightly

depressed compared with the surrounding tan viable

parenchyma, creating “nutmeg liver”

(so called because it resembles the cut surface of a nutmeg).

(B) Microscopic preparation shows centrilobular hepatic

necrosis with hemorrhage and scattered inflammatory cells.

Petechiae

Hemorrhage, defined as the extravasation of blood from vessels, is most often

the result of damage to blood vessels or defective clot formation.

•

capillary bleeding can occur in chronically congested tissues.

•

Trauma.

•

atherosclerosis.

•

or inflammatory or neoplastic erosion of a vessel wall also may lead to hemorrhage.

♦Bleeding may be extensive if the affected vessel is a large vein or artery.

♦

The risk of hemorrhage is increased in a wide variety of clinical disorders collectively

called:

hemorrhagic diatheses

.

Including:

inherited or acquired defects in:

•

vessel walls.

•

platelets.

•

or coagulation factors.

♦Hemorrhage may be manifested by different appearances and clinical

consequences.

♦

Hemorrhage may be

external

or accumulate within a tissue as a

hematoma

,

which ranges in significance from trivial to fatal.

♦Large bleeds into body cavities are described variously according to location

• hemothorax.

• hemopericardium.

• hemoperitoneum.

• hemarthrosis (in joints).

are minute (1 to 2 mm in diameter) hemorrhages into skin, mucous membranes, or

serosal surfaces causes include :

•

low platelet counts (thrombocytopenia).

•

defective platelet function.

•

and loss of vascular wall support, as in vitamin C deficiency.

Hemorrhage

Ecchymoses

are slightly larger (3 to 5 mm) hemorrhages.

Purpura can result from

:

•

the same disorders that cause petechiae.

•

Trauma

vascular inflammation (vasculitis), and increased vascular fragility.

are larger (1 to 2 cm) subcutaneous hematomas (colloquially called bruises).

♦ Extravasated red cells are phagocytosed and degraded by macrophages; the

characteristic color changes of a bruise result from the enzymatic conversion of

hemoglobin

(red-blue color) to

bilirubin

(blue-green color) and eventually

hemosiderin

(golden-brown).

♦

The clinical significance of any particular hemorrhage depends on:

•

the volume of blood that is lost.

•

the rate of bleeding..

•

The site of hemorrhage also is important.

♦

chronic or recurrent external blood loss culminates in iron deficiency anemia

♦

By contrast, iron is efficiently recycled from phagocytosed red cells,

so internal

bleeding (e.g., a hematoma) does not lead to iron deficiency.

Purpura

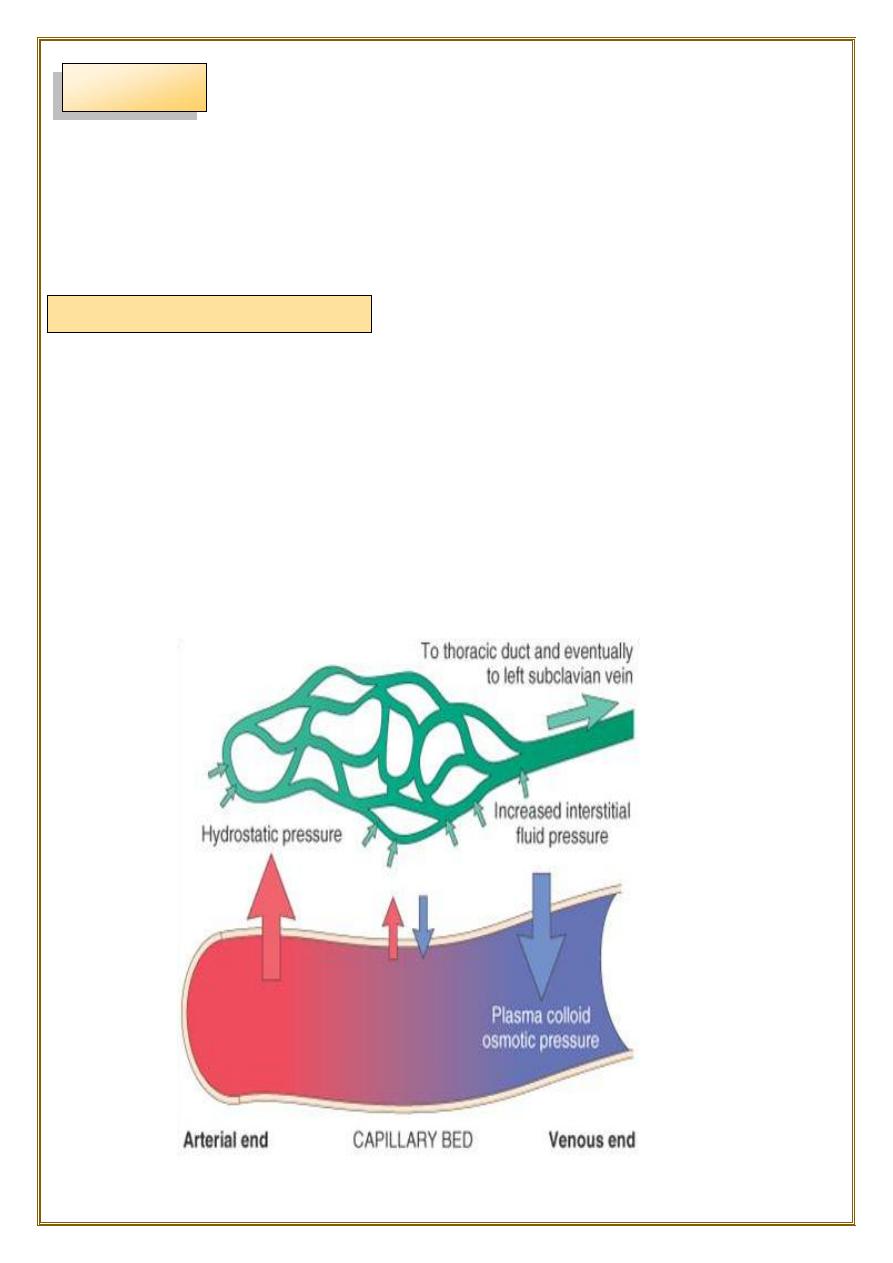

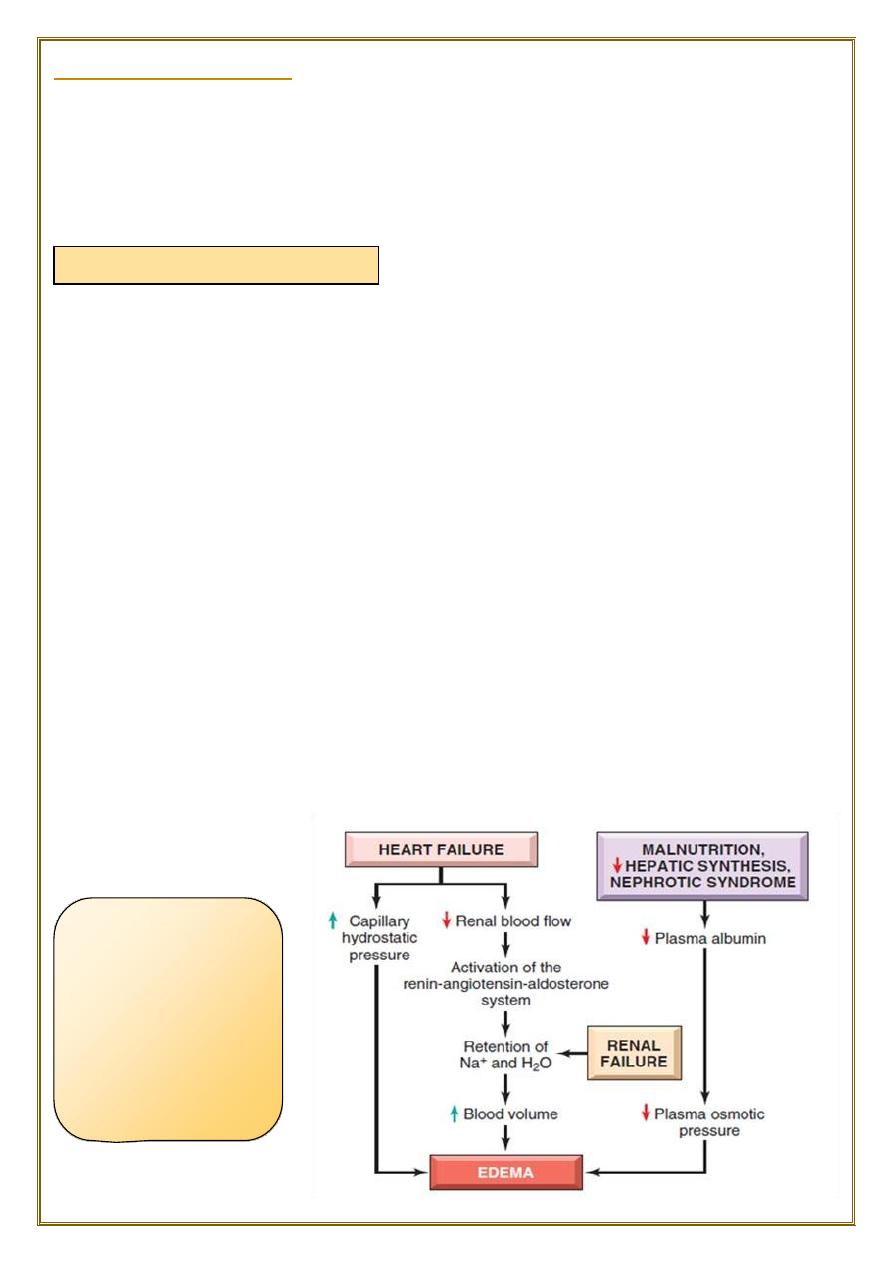

Mechanism of edema formation:

Definition:

edema is an accumulation of interstitial fluid within tissues.

Extravascular fluid can also collect in body cavities such as:

a) Hydrothorax.

b) Hydropericardium .

c) Hydroperitoneum (ascites) Anasarca.

♦Approximately 60% of lean body weight is water, two thirds of which is

intracellular.

Most of the remaining water is found in extracellular compartments in the form of

interstitial fluid; only 5% of the body’s water is in blood plasma.

♦

The capillary endothelium acts as a semi permeable membrane and highly

permeable to water & to almost all solutes in plasma with an exception of proteins.

Normally, any outflow of fluid into the interstitium from the arteriolar end of the

microcirculation is nearly balanced by inflow at the venular end. Therefore,

normally, there is very little fluid in the interstitium.

EDEMA

1) Increased Hydrostatic pressure

Renal failure also

cause edema

because of retention

of Na and water

leads to increase

blood volume

(increase hydrostatic

pressre).

causes of Edema are:

1) Increased Hydrostatic pressure.

2) Decrease plasma Oncotic pressure.

3) Increased vascular permeability.

4) Lymphatic channels obstruction.

5) Sodium retention.

♦

mainly caused by

disorders that impair venous return.

♦Local increases in intravascular pressure caused, for example, by deep venous

thrombosis in the lower extremity can cause edema restricted to the distal portion of

the affected leg.

♦Generalized increases in venous pressure, with resultant systemic edema, occur

most commonly in congestive heart failure.

Several factors increase venous hydrostatic pressure in patients with

congestive heart failure.

•

The reduced cardiac output leads to

systemic venous congestion

.

•

reduction in cardiac output results in hypoperfusion of the kidneys, triggering the

reninangiotensin-aldosterone axis

and inducing sodium and water retention

(secondary hyperaldosteronism)

.

♦

a vicious circle of fluid retention, increase blood volume, increased venous

hydrostatic pressures, and worsening edema ensues.

Unless cardiac output is restored or renal water retention is reduced this

vicious circle continues.

Nephrotic syndrome

3) Increased Vascular permeability:

•

Reduction of plasma

albumin

concentrations.

•

Under normal circumstances, albumin accounts for almost

half

of the total plasma

protein.

Common causes of reduced plasma osmotic pressure:

•

Albumin lost from the circulation.

•

Or albumin synthesized in inadequate amounts.

•

is the most important cause of albumin loss from the blood.

•

the glomerular capillaries become leaky, leading to the loss of albumin (and other

plasma proteins) in the urine and the development of

generalized edema

.

•

Reduced albumin synthesis occurs in the setting of severe liver disease (e.g.,

cirrhosis) and protein malnutrition.

low albumin levels lead to edema, reduced intravascular volume, renal

hypoperfusion, and secondary hyperaldosteronism. Increased salt and water retention

by the kidney fails to correct the plasma volume deficit and exacerbates the edema,

because the primary defect— low serum protein—persists.

•

usually occurs due to acute inflammation.

•

In inflammation, chemical mediators are produced.

Some of these mediators cause increased vascular permeability which leads to loss of

fluid & high molecular weight albumin and globulin into the interstitium.

Inflammatory edema differs from non inflammatory edema by the following

features:

a) Inflammatory edema (exudate)

•

Due to inflammation-induced increased permeability and leakage of plasma proteins.

•

Forms an exudate [protein rich]

Specific gravity > 1.012

b) Non-inflammatory oedema (transudate)

•

A type of edema occurring in hemodynamic derangement (i.e. increased plasma

hydrostatic pressure & decreased plasma oncotic pressure.)

•

Formed transudate [protein poor]

•

Specific gravity < 1.012.

2) Decrease plasma Oncotic pressure

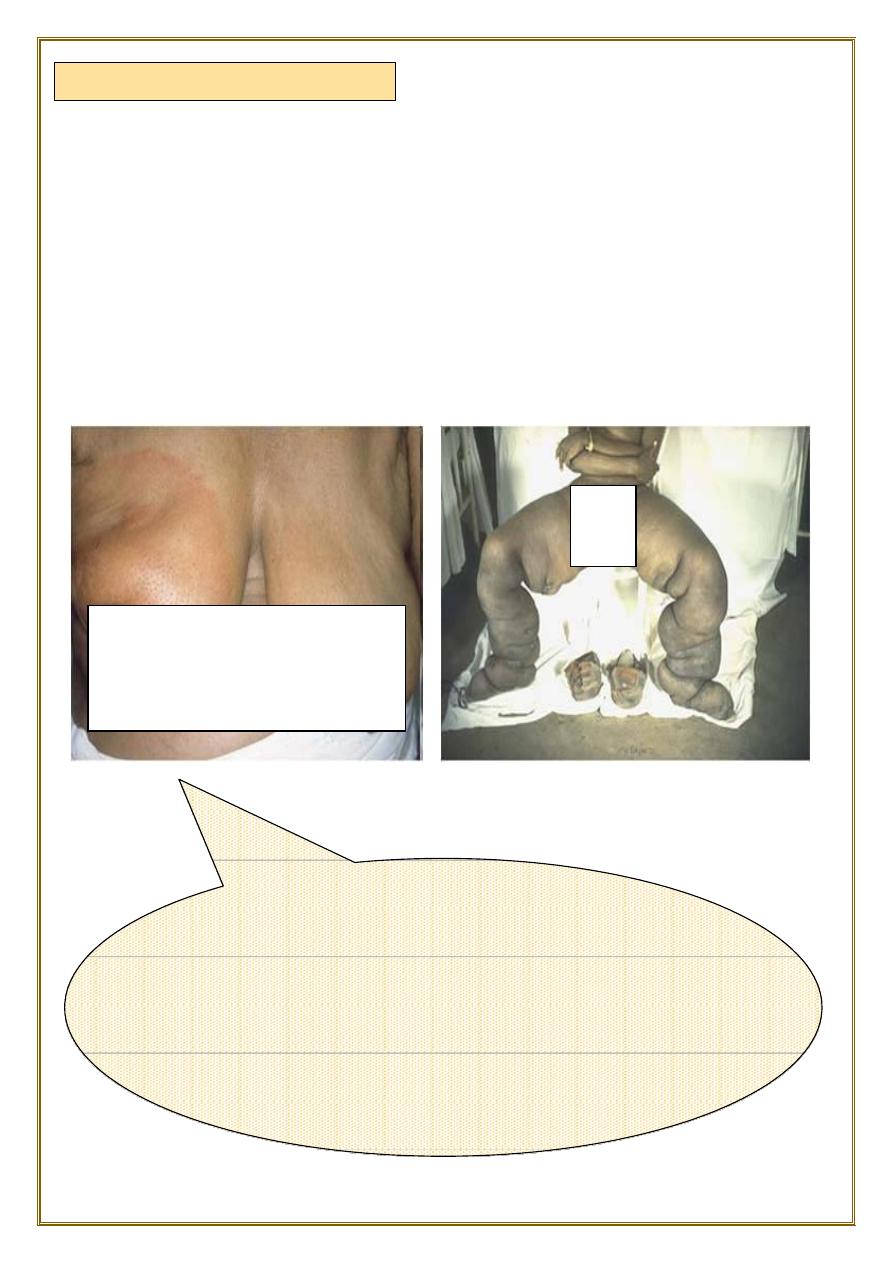

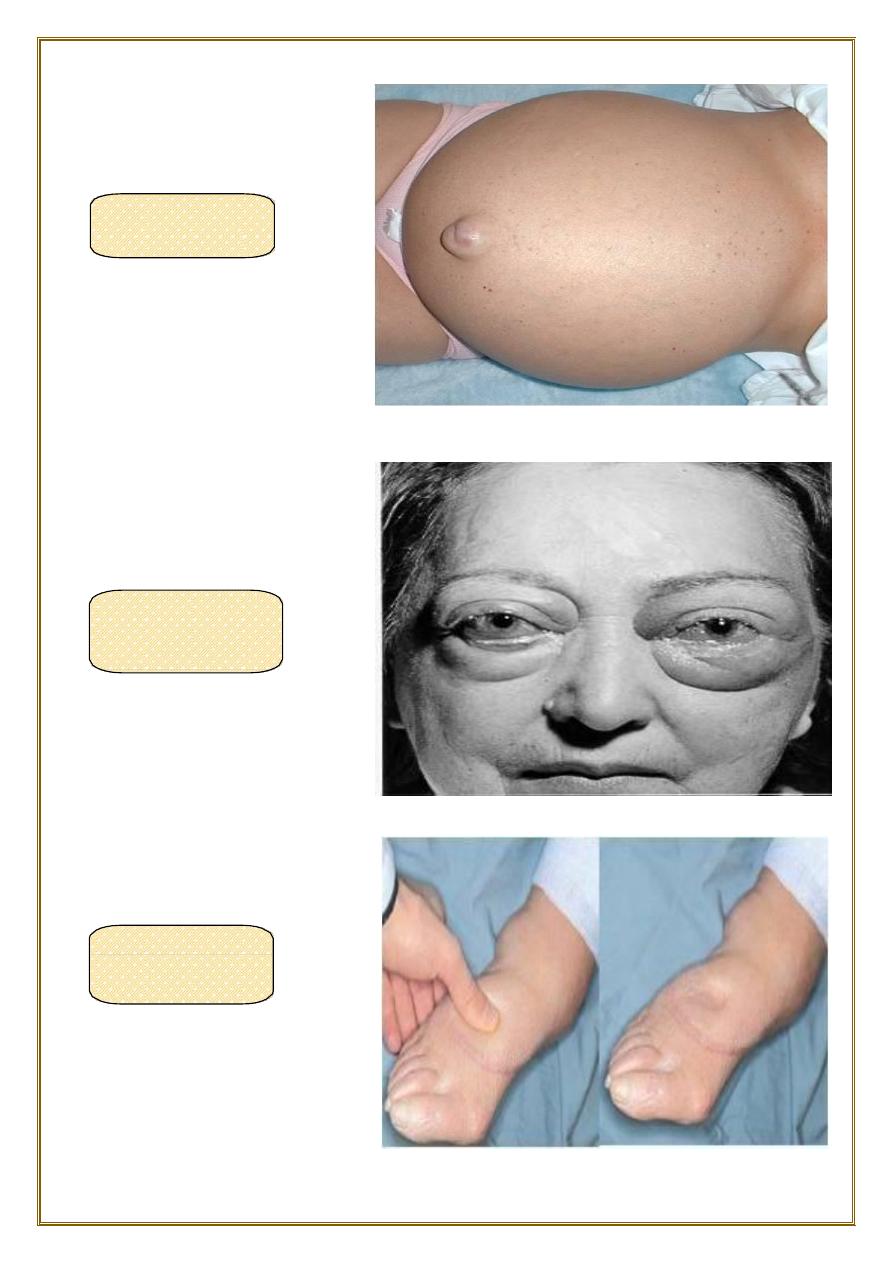

Breast, lymphedema secondary to breast carcinoma

– Clinical presentation Breas t cancer cells have blocked

the lymphatic channels draining fluid from the skin of

the right breast, leading to passive congestion and

resulting in a peau d'orange( orange skin) appearance.

Compare with the normal left breast.

♦

Edema may result from lymphatic obstruction that compromises resorption of fluid

from interstitial spaces. Impaired lymphatic drainage and consequent lymphedema It

usually results from a localized obstruction caused by an

inflammatory

or

neoplastic

conditions.

♦For example, the parasitic infection filariasis can cause massive edema of the

lower extremity and external genitalia (so-called “

elephantiasis

”) by

producing

inguinal lymphatic and lymph node fibrosis.

Infiltration and obstruction of superficial lymphatics by

breast cancer

may cause

edema of the overlying skin; the characteristic finely pitted appearance of the skin of

the affected breast is called peau d’orange (orange peel).

4) Lymphatic channels obstruction

5) Sodium and water retention

Morphology of edema

♦Subcutaneous edema

♦

Lymphedema also may occur as a complication of

therapy

. in women with breast

cancer who undergo axillary lymph node

resection

and/or

irradiation

, both of which

can disrupt and obstruct lymphatic drainage, resulting in severe

lymphedema of the

arm

.

♦

Excessive retention of salt (and its obligate associated water) can lead to edema by

increasing hydrostatic pressure (because of expansion of the intravascular volume)

and reducing plasma osmotic pressure.

♦

Excessive salt and water retention are seen in a wide variety of diseases that

compromise renal function, including poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and acute

renal failure.

♦

Causes of sodium and water retention:

1- excessive salt intake with renal insufficiency.

2- increased tubular reabsorption of sodium.

3-

Renal hypo perfusion.

4-

Increased renin- angiotensin- aldosterone secretion.

♦Gross examination:

clearing and separation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) elements. edema most

commonly encountered in:

•

subcutaneous tissues,

•

lungs,

•

and brain.

•

can be diffuse.

•

but usually accumulates preferentially in parts of the body where hydrostatic

pressures are highest.

edema typically is most pronounced in the legs with standing and the sacrum

with recumbency.

• dependent edema. Finger pressure over edematous subcutaneous tissue displaces

the interstitial fluid, leaving a finger-shaped depression; this appearance is called

pitting edema

.

•

Edema resulting from renal dysfunction or nephrotic syndrome often manifests first

in

loose connective tissues (e.g., the eyelids, causing periorbital edema).

PERI ORBITAl

EDEMA

“PITTING”

EDEMA

ASCITES

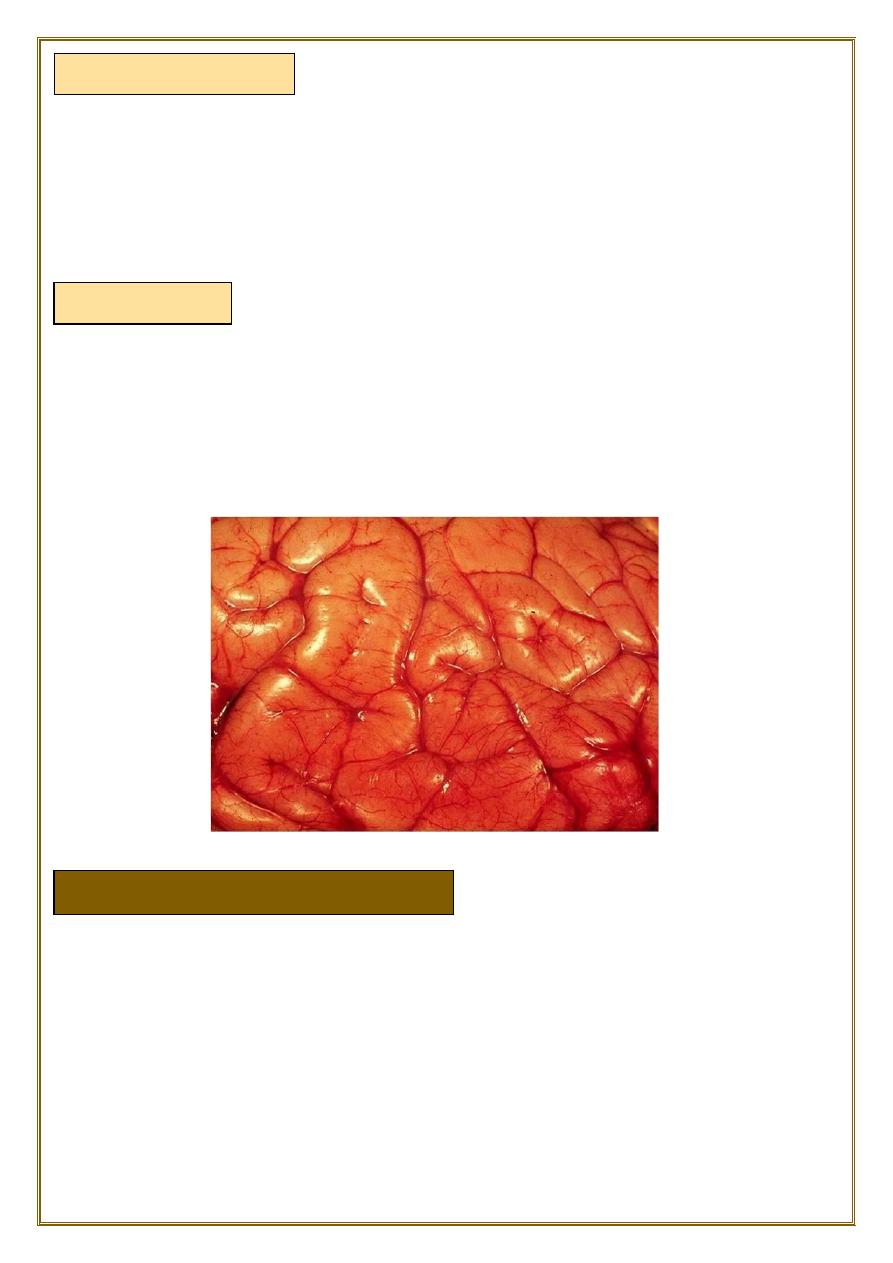

♦Brain edema

HEMOSTASIS AND THROMBOSIS

•

the lungs often are two to three times their normal weight,

•

and sectioning shows frothy, sometimes blood-tinged fluid.

consisting of a mixture of:

•

air.

•

edema fluid.

•

and extravasated red cells.

can be:

•

localized (e.g., because of abscess or tumor).

•

generalized depending on the nature and extent of the pathologic process or injury.

With generalized edema:

•

The

sulci

are narrowed .

•

The

gyri

swell and become flattened against the skull.

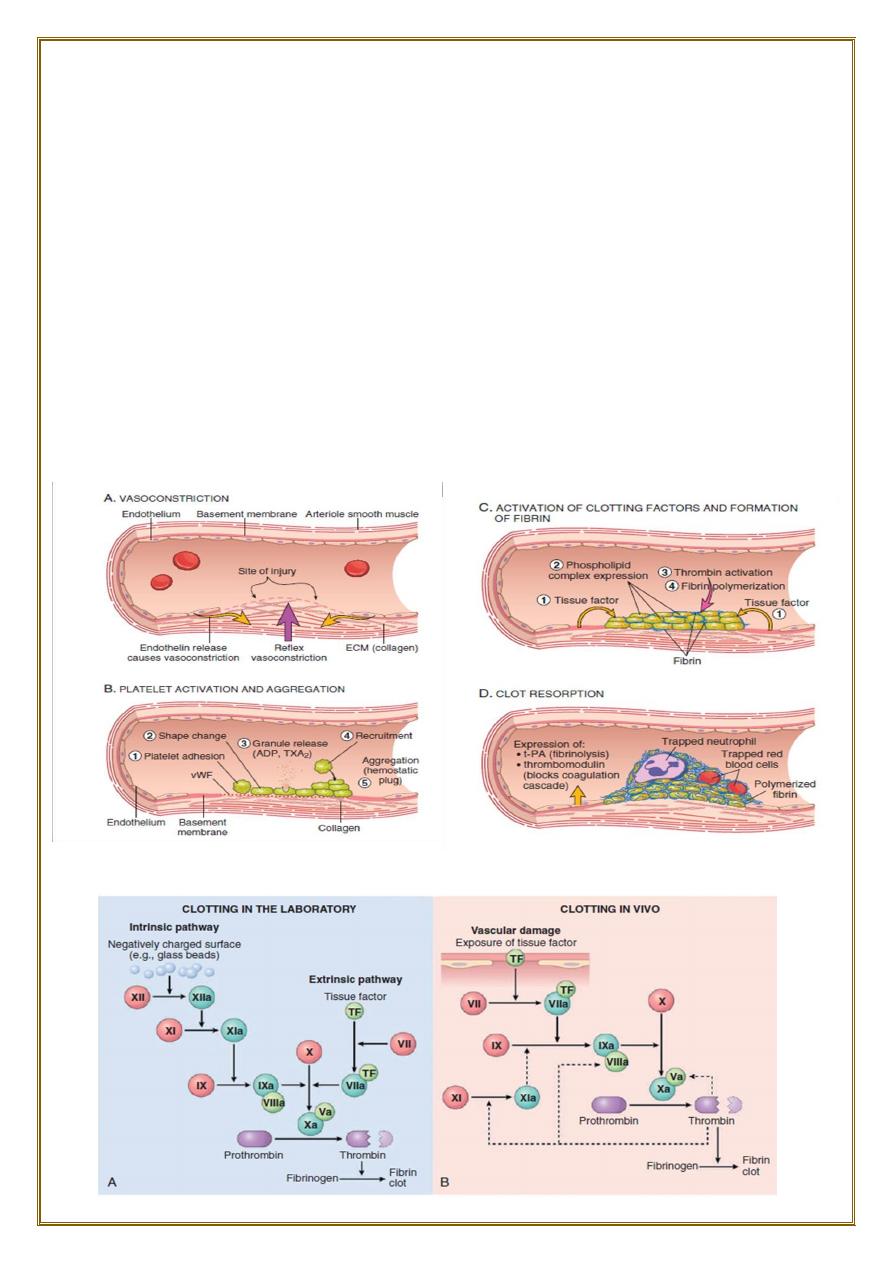

♦Normal hemostasis

•

comprises a series of regulated processes that culminate in the formation of a blood

clot that limits bleeding from an injured vessel.

•

The pathologic counterpart of hemostasis is thrombosis, the formation of blood clot

(thrombus) within non-traumatized, intact vessels.

♦Pulmonary edema

•

(A) After vascular injury

, local neurohumoral factors induce a transient

vasoconstriction.

•

(B) Platelets bind via glycoprotein Ib

(GpIb) receptors to von Willebrand factor

(VWF) on exposed ECM and are activated, undergoing a shape change and granule

release. Released ADP and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) induce additional platelet

aggregation through platelet GpIIb-IIIa receptor binding to fibrinogen, and form the

primary hemostatic plug.

•

(C) Local activation of the coagulation cascade

results in fibrin polymerization,

“cementing” the platelets into a definitive secondary hemostatic plug.

•

(D) Counterregulatory mechanisms

, mediated by tissue plasminogen activator (t-

PA, a fibrinolytic product) and thrombomodulin, confine the hemostatic process to

the site of injury.

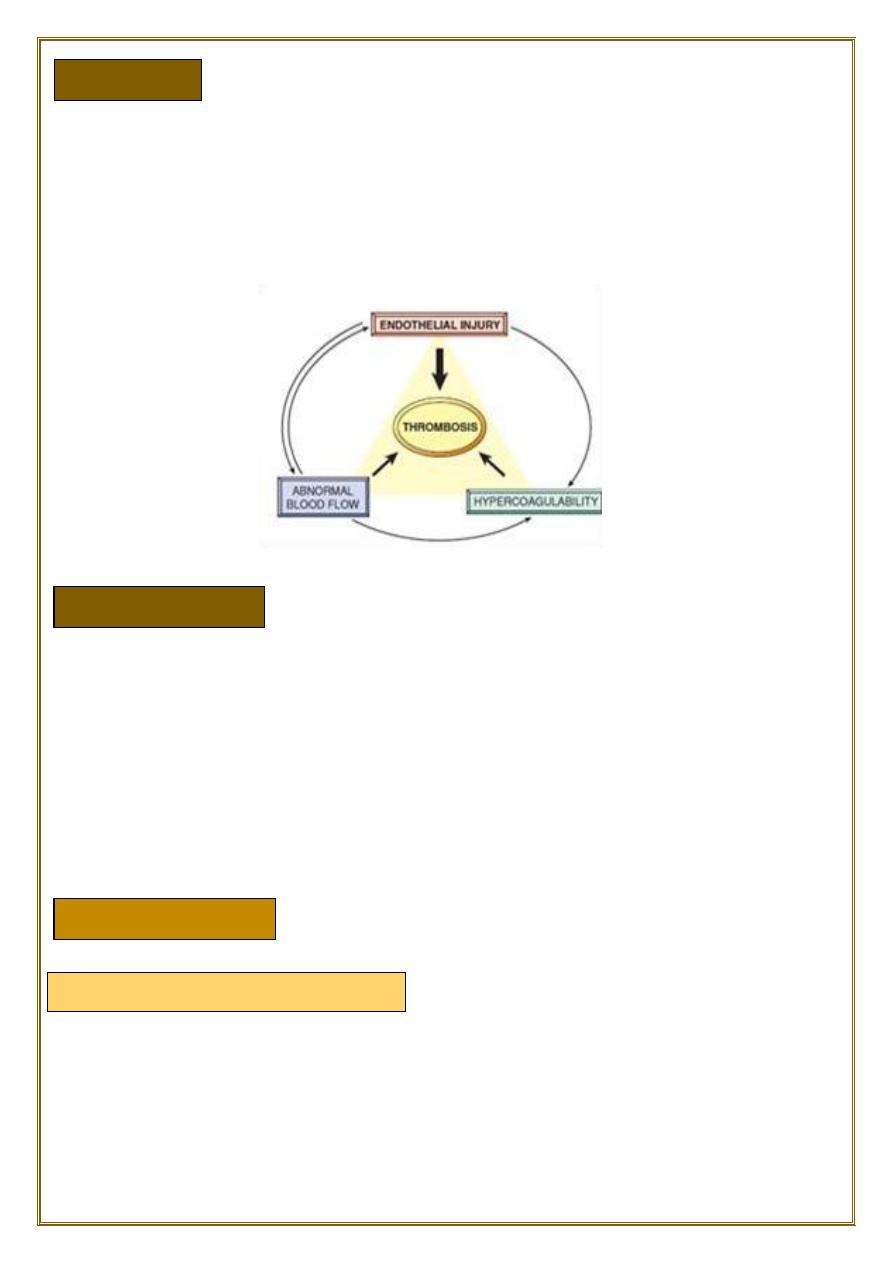

Endothelial injury

Abnormal Blood Flow

•

The pathologic counterpart of hemostasis is thrombosis, the formation of blood clot

(thrombus) within non-traumatized, intact vessels.

The primary abnormalities that lead to intravascular thrombosis are:

(1) endothelial injury.

(2) stasis or turbulent blood flow.

(3) hypercoagulability of the blood (the so-called “Virchow triad”).

•

Endothelial injury leading to platelet activation.

underlies thrombus formation in the

heart and the arterial circulation

, where the

high rates of blood flow impede clot formation.

This is the reason behind the use of aspirin and other platelet inhibitors in coronary

artery disease and acute myocardial infarction.

severe endothelial injury may trigger thrombosis by exposing VWF and tissue factor.

Most common examples are:

•

Endocardial injury during myocardial infarction.

•

Injury over ulcerated plaque in severely atherosclerotic arteries.

contributes to:

•

arterial thrombosis.

•

cardiac thrombosis

by causing:

•

endothelial injury or dysfunction.

•

forming countercurrents and local pockets of stasis.

Thrombosis

Turbulence (chaotic blood flow)

Hypercoagulability

is a major factor in the development of venous thrombi.

Under conditions of normal

laminar blood flow

, platelets (and other blood cells) are

found mainly in the

center

of the vessel lumen.

separated from the endothelium by a slower-moving layer of plasma.

stasis and turbulence have the following deleterious effects:

•

Both promote endothelial cell activation and enhanced procoagulant activity.

•

Stasis allows platelets and leukocytes to come into contact with the endothelium

when the flow is sluggish.

•

Stasis also slows the washout of activated clotting factors and impedes the inflow of

clotting factor inhibitors.

Turbulent and static blood flow contributes to thrombosis in a number of

clinical settings.

Ulcerated atherosclerotic plaques

expose subendothelial ECM ,turbulence.

aneurysms

create local stasis.

Acute myocardial infarction

results in focally noncontractile myocardium.

Ventricular remodeling after more remote infarction can lead to aneurysm formation.

cause local blood stasis.

Mitral valve stenosis

(e.g., after rheumatic heart disease) results in left atrial

dilation. In conjunction with atrial fibrillation, a dilated atrium also produces stasis

and is a prime location for the development of thrombi.

Hyperviscosity syndromes

(such as polycythemia vera,) increase resistance to flow

and cause small vessel stasis;

sickle cell anemia

the deformed red cells cause vascular occlusions, and the

resultant stasis also predisposes to thrombosis.

• Hypercoagulability refers to an abnormally high tendency of the blood to clot,

and is typically caused by alterations in coagulation factors.

•

It is an important underlying risk factor for venous thrombosis.

•

can be divided into:

primary (genetic) and secondary (acquired) disorders.

STASIS

♦Secondary (Acquired)

Common (>1% of the Population)

Factor V mutation.

Prothrombin mutation.

Increased levels of factor VIII, IX, or XI or fibrinogen.

♦ Rare

Anti-thrombin III deficiency .

Protein C deficiency.

Protein S deficiency.

Prolonged bed rest or immobilization.

Myocardial infarction.

Atrial fibrillation.

Tissue injury (surgery, fracture, burn).

Cancer.

Prosthetic cardiac valves.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation .

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

•

Thrombi can develop anywhere in the cardiovascular system.

•

Arterial or cardiac thrombi

typically arise at sites of endothelial injury or

turbulence;

•

venous thrombi

characteristically occur at sites of stasis.

•

Thrombi are

focally attached to the underlying vascular surface

.

•

propagate toward the heart:

•

arterial thrombi grow

in a

retrograde

direction from the point of attachment,

•

venous thrombi

extend in the

direction

of blood flow.

•

The propagating portion of a thrombus tends to be poorly attached and therefore

prone to fragmentation and migration through the blood as an

embolus

.

•

Thrombi can have grossly (and microscopically) apparent laminations called lines

of Zahn

.

•

these represent pale platelet and fibrin layers alternating with darker red cell–rich

layers.

•

Such lines are significant in that they are only found in thrombi that form in flowing

blood;

♦Primary (Genetic)

MORPHOLOGY

•

their presence can therefore usually distinguish

antemortem thrombosis from the

bland nonlaminated post mortum thrombi

.

•

Although thrombi formed in the “low-flow”

venous system

superficially resemble

postmortem clots, careful evaluation generally shows

ill-defined laminations

.

•

Thrombi occurring in heart chambers or in the aortic lumen are designated as

mural thrombi

.

♦Arterial thrombi

•

are frequently occlusive.

•

They are typically rich in platelets, as the processes underlying their development

(e.g., endothelial injury) lead to platelet activation.

•

Although usually superimposed on a ruptured

atherosclerotic plaque

, other

vascular injuries (

vasculitis, trauma

) can also be underlying causes.

♦Venous thrombi (phlebothrombosis):

•

are almost invariably occlusive;

•

they frequently propagate some distance toward the heart, forming a long cast

within the vessel lumen that is prone to give rise to emboli.

•

they contain more enmeshed red cells, leading to the moniker red, or stasis,

thrombi.

•

The veins of the lower extremities are most commonly affected.

♦

At autopsy, postmortem clots are:

• gelatinous

and because of red cell settling they have a dark red dependent portion and a

yellow “chicken fat” upper portion;

they also are usually not attached to the underlying vessel wall.

♦By contrast, red thrombi typically are:

firm,

focally attached to vessel walls,

and the contain gray strands of deposited fibrin.

Thrombi on heart valves are called vegetations.

•

Propagation.

The thrombus enlarges through the accretion of additional

platelets and fibrin, increasing the odds of vascular occlusion.

•

Embolization

. Part or all of the thrombus is dislodged and transported elsewhere

in the vasculature.

•

Dissolution

. fibrinolytic factors may lead to its rapid shrinkage and complete

dissolution.

•

Organization and recanalization

. Older thrombi become organized by the

ingrowth of

endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts

.

♦

In time, capillary channels are formed reestablishing the continuity of the original

lumen.

♦

Further recanalization can sometimes convert a thrombus into a vascularized mass

of connective tissue that is eventually incorporated into the wall of the remodeled

vessel.

Fate of the Thrombus

Most venous thrombi occur in the superficial or the deep veins of the leg.

Superficial venous thrombi

usually arise in the saphenous system.

particularly in the setting of varicosities.

these rarely embolize.

but they can be painful.

and can cause local congestion.

and swelling from impaired venous outflow,

predisposing the overlying skin to the development of infections and varicose

ulcers.

Deep venous thrombosis DVT

(DVTs) in the larger leg veins at or above the knee joint (e.g., popliteal, femoral,

and iliac veins).

are more serious because they are prone to embolize.

Although such DVTs may cause local pain and edema, collateral channels often

circumvent the venous obstruction. Consequently, DVTs are entirely asymptomatic

in approximately 50% of patients and

are recognized only after they have embolized

to the lungs

.

DVTs are associated with stasis and hypercoagulable states.

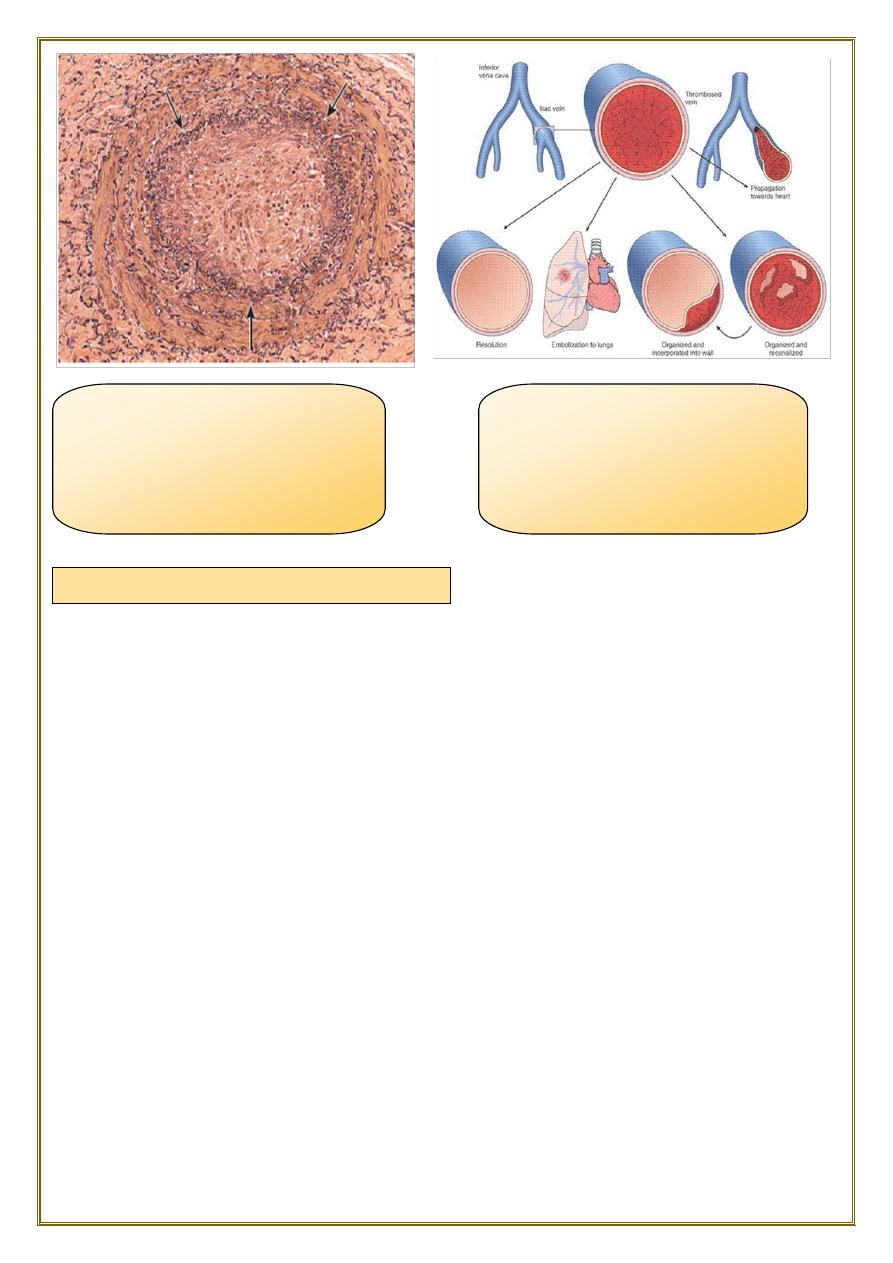

Fig. An organized thrombus. Low-

power view of a thrombosed artery

stained for elastic tissue. The original

lumen is delineated by the internal

elastic lamina (arrows) and is

completely filled with organized

thrombus.

deep pelvic vein thrombus, the

prime source of pulmonary emboli,

the other source would be deep

pelvic veins. superficial vein

thromboses do not usually

embolize to the lungs.

Venous Thrombosis (Phlebothrombosis)

•

An embolus is a detached intravascular solid, liquid, or gaseous mass that is carried

by the blood from its point of origin to a distant site, where it often causes tissue

dysfunction or infarction.

The vast majority of emboli derive from a dislodged thrombus—hence the term

thromboembolism

.

Less commonly, emboli are composed of:

• fat droplets.

bubbles of air or nitrogen.

tumor fragments.

bits of bone marrow.

or amniotic fluid.

•

Inevitably, emboli lodge in vessels too small to permit further passage, resulting in

partial or complete vascular occlusion

.

•

depending on the

site of origin

, emboli can arrest anywhere in the vascular tree.

The primary consequence of systemic embolization

•

is ischemic necrosis (infarction) of downstream tissues,

•

whereas embolization in the pulmonary circulation leads to

hypoxia ,hypotension,

and rightsided heart failure

.

•

Pulmonary emboli originate from deep venous thrombosis and are responsible for

the most common form of thromboembolic disease

.

•

In more than 95% of cases, venous emboli originate from thrombi within deep leg

veins proximal to the popliteal fossa.

•

Fragmented thrombi from DVTs are carried through progressively

larger channels

and usually pass through the

right side

of the heart before arresting in the

pulmonary vasculature.

Depending on size, a PE can occlude:

•

the main pulmonary artery,

•

lodge at the bifurcation of the right and left pulmonary arteries (saddle embolus),

•

or pass into the smaller, branching arterioles.

EMBOLISM

Pulmonary Thromboembolism

the major clinical and pathologic features are the following:

♦

Most pulmonary emboli (60%–80%) are small and

clinically silent

.

With time, they undergo organization and become incorporated into the vascular

wall. At the other end of the spectrum, a large embolus that blocks a major

pulmonary artery can cause

sudden death

.

♦

Embolic obstruction of medium-sized arteries and subsequent rupture of

downstream capillaries rendered anoxic can cause

pulmonary hemorrhage

. Such

emboli do not usually cause pulmonary infarction because the area also receives

blood through an intact bronchial circulation (dual circulation).

However, a similar embolus in the setting of left-sided cardiac failure (and

diminished bronchial artery perfusion) can lead to a

pulmonary hypertension and

pulmonary infarct

.

♦

Embolism to small end-arteriolar pulmonary branches usually causes infarction.

♦

Multiple emboli occurring through time can cause and right ventricular failure (cor

pulmonale).

•

Systemic thromboembolism refers to emboli travelling within arterial circulation &

impacting in the systemic arteries.

•

Most systemic emboli (80%) arise from intracardiac mural thrombi.

•

two thirds of intracardiac mural thrombi are associated with left ventricular wall

infarcts.

•

and another quarter with dilated left atria secondary to rheumatic valvular heart

disease.

Systemic thromboembolism

•

The remaining (20%) of systemic emboli arise from :

thrombi on ulcerated athrosclerotic plaques.

or fragmentation of valvular vegetation.

Aortic aneurysm.

Paradoxical emboli from venous side.

•

Unlike venous emboli, which tend to lodge primarily in one vascular bed

(the lung), arterial emboli can travel to a wide variety of sites.

-the

lower extremities

(75%).

-&

the brain

(10%).

-with the rest lodging in the

intestines

,

kidney

&

spleen

.

•

The consequences of embolization depend on:

•

the caliber of the occluded vessel.

•

the collateral supply.

•

and the affected tissue’s vulnerability to anoxia.

••

arterial emboli often lodge in end arteries and cause infarction

.

•

Fat embolism usually follows fracture of bones and other type of tissue injury.

•

After the injury, globules of fat frequently enter the circulation.it is asymptomatic in

most cases and fat is removed.

•

But in some severe injuries the fat emboli may cause occlusion of

pulmonary or

cerebral

microvasculature

•

fat embolism syndrome may result.

Fat embolism syndrome

•

typically begins 1 to 3 days after injury during which the raised tissue pressure

caused by swelling of damaged tissue forces fat into marrow sinosoid & veins.

•

The features of this syndrome are

:

-a sudden onset of dyspnea, blood stained sputum, tachycardia.

-mental confusion with neurologic symptoms sometimes progress to delirium &

coma.

Fat Embolism

Gas bubbles within the circulation can obstruct vascular flow and cause distal

ischemic injury almost as readily as thrombotic masses.

♦

Air may enter the circulation during:

Obstetric procedures

Chest wall injury

In deep see divers & under water construction workers.

Neck wounds penetrating the large veins

Cardio thoracic surgery.

Arterial catheterisation& intravenous infusion.

♦

Generally, in excesses of 100cc is required to have a clinical effect and 300cc or

more may be fatal.

♦

The bubbles act like physical obstructions and may coalesce to form a frothy mass

sufficiently large to occlude major vessels.

It is a grave but uncommon, unpredictable complication of labour which may

complicate vaginal delivery, caesarean delivery and abortions

. It had mortality rate

over 80%. The amniotic fluid containing fetal material enters via the placental bed &

the ruptured uterine veins.

Leads to:

•

hypotensive shock

•

seizure & coma

•

pulmonary edema

•

50% of the cases will develop DIC

Air embolism

Amniotic fluid embolism

♦

Definition:

An infarct is an area of ischemic necrosis caused by occlusion of the vascular supply

to the affected tissue.

Infarction primarily affecting the heart and the brain is a

common and extremely important cause of clinical illness.

♦

Causes:

•

Arterial thrombosis or arterial embolism underlies the vast majority of infarctions.

♦

Less common causes of arterial obstruction include:

1. vasospasm,

2. expansion of an atheroma secondary to intraplaque hemorrhage.

3. and extrinsic compression of a vessel, such as by tumor, a dissecting aortic

aneurysm.

4. Other uncommon causes of tissue infarction include vessel twisting (e.g., in

testicular torsion or bowel volvulus).

Factors That Influence Infarct Development

♦

Anatomy of the vascular supply.

The presence or absence of an

alternative blood supply lung

by the pulmonary and

bronchial arteries means that obstruction of the pulmonary arterioles does not cause

lung infarction unless the bronchial circulation also is compromised.

Similarly, the

liver

, which receives blood from the hepatic artery and the portal vein,

and the

hand and forearm

, with its parallel radial and ulnar arterial supply, are

resistant to infarction. By contrast, the

kidney and the spleen both have end-arterial

circulations

.

♦

Rate of occlusion.

Slowly developing occlusions are less likely to cause infarction because they allow

time for the development of

collateral

blood supplies. For example, small

interarteriolar anastomoses, which normally carry minimal blood flow, interconnect

the three major coronary arteries.

♦

Tissue vulnerability to hypoxia.

Neurons

undergo irreversible damage when deprived of their blood supply for only 3

to 4 minutes.

Myocardial cells

, although hardier than neurons, still die after only 20

to 30 minutes of ischemia. By contrast,

fibroblasts

within myocardium remain viable

after many hours of ischemia.

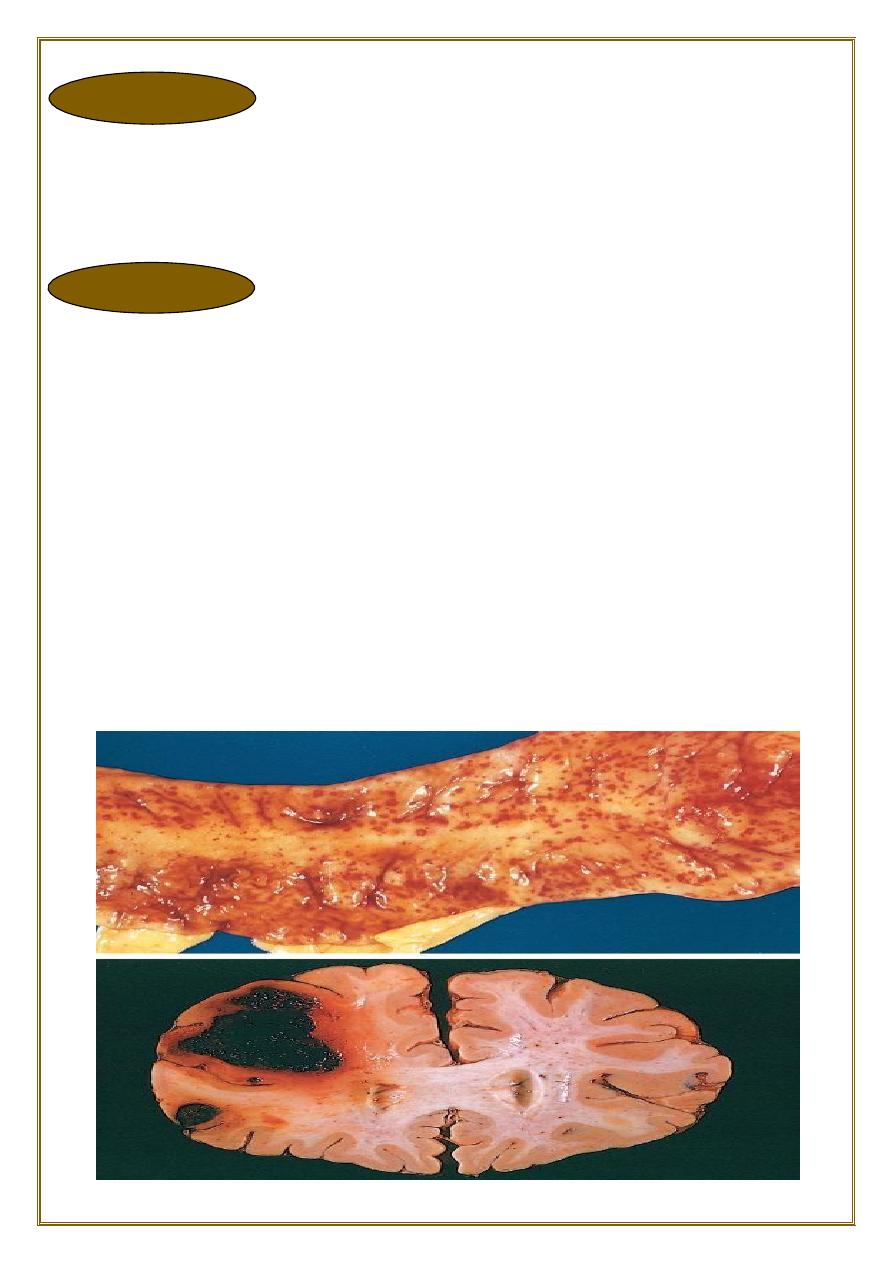

Morphology of infarcts

Types of infarcts Infarcts are classified depening on:

A) the basis of their colour (reflecting the amount of haemorrhage) into

:

1. Hemorrhagic (Red) infarcts.

2. Anemic (White) infarcts.

Infract

B) the presence or absence of microbial infection into

:

1. Septic infarcts.

2. Bland infarcts.

•Red infarcts occur in:

a)

Venous occlusions as in ovarian torsion

b)

Loose tissues

such as the lung which allow blood to collect in infarct zone.

c

) Tissues with dual circulations

(e.g. the lung), permitting flow of blood from

unobstructed vessel in to necrotic zone.

d) In

tissues

that were previously congested because of sluggish outflow of blood.

e) When

blood flow

is reestablished to a site of previous arterial occlusion &

necrosis.

•

White infarcts occur in:

a)

Arterial occlusion

in organs with a single arterial blood supply.

b)

Solid organs

such as the heart, spleen, & kidney, where the solidity of the tissue

limits the amount of hemorrage that can percolate or seep in to the area of ischemic

necrosis from the nearby capillaries.

•

Gross:

All infarcts are

wedge-shaped

with the occluded vessel at the apex and the periphery

of the organ forming the base of the wedge. The infarction will induce inflammation

in the tissue surrounding the area of infarction.

Following

inflammation

, some of the infarcts may show recovery, however, most are

ultimately replaced with scars

except in the brain

.

•

Microscopy:

The dominant histologic feature of infarction is ischemic coagulative necrosis. The

brain is an exception to this generalization, where liquifactive necrosis is common.

♦

Definition:

Shock is a state in which diminished cardiac output or reduced effective circulating

blood volume impairs tissue perfusion and leads to cellular hypoxia.

♦

Its causes fall into three general categories:

♦Cardiogenic shock

results from low cardiac output as a result of myocardial pump failure. It may be

caused by myocardial damage (infarction), ventricular arrhythmias, extrinsic

compression (cardiac tamponade) or outflow obstruction (e.g.,

pulmonaryembolism).

♦Hypovolemic shock

results from low cardiac output due to loss of blood or plasma volume (e.g., resulting

from hemorrhage or fluid loss from severe burns).

♦Septic shock

is triggered by microbial infections and is associated with severe systemic

inflammatory response syndrome(SIRS). In addition to microbes, SIRS may be

triggered by a variety of insults, including burns, trauma, and/or pancreatitis.

The common pathogenic mechanism is a massive outpouring of inflammatory

mediators from innate and adaptive immune cells that produce

:

•

arterial vasodilation.

•

vascular leakage.

•

and venous blood pooling.

These cardiovascular abnormalities result in tissue hypoperfusion, cellular hypoxia,

and metabolic derangements that lead to organ dysfunction and, if severe and

persistent, organ failure and death.

•

Pathogenesis of septic shock:

-It results from the spread & expansion of an initially localized infection like

pneumonia into the blood stream.

-Most causes of septic shock (~70%) are caused by endotoxin-producing gram-

negative bacilli, hence the term endotoxic shock.

•

Septic shock acting on:

•

The heart

– causing decreased myocardial contractility which results in low cardiac

output,

•

Blood vessel

– causing systemic vasodilation

•

The mediators

also cause widespread endothelial injury & activation of the

coagulation system resulting in DIC.

•

Lung

– causing alveolar capillary damage resulting in adult respiratory distress

syndrome (ARDS).

Shock

♦Anaphylactic shock

results from systemic vasodilation and increased vascular permeability that is

triggered by an immunoglobulin E–mediated hypersensitivity reaction.

Less commonly, shock can result from a loss of vascular tone associated with

anesthesia or secondary to a spinal cord injury (

neurogenic shock

).

Stages of shock

Uncorrected shock passes through 3 important stages:

1)

An initial nonprogressive phase

during which reflex compensatory mechanisms are activated and vital organ

perfusion is maintained.

2)

Progressive stage (Established shock)

- characterized by tissue hypoperfusion and onset of worsening circulatory and

metabolic derangement, including acidosis.

3)

An irreversible stage

- in which cellular and tissue injury is so severe that even if the hemodynamic

defects are corrected, survival is not possible.

Morphology of shock:

All organs are affected in severe shock. In shock, there is widespread tissue

hypoperfusion involving various organs such as the heart, brain, & kidney.

widespread hypoxic tissue necrosis.

The widespread tissue necrosis manifests as

multiple organ dysfunction [MODS].

And

lungs may show ARDS

.