Medicine

Notes…

1

Lecture.9 Oedema and Ascites

Oedema

• Oedema is caused by an excessive accumulation of fluid within the interstitial

space.

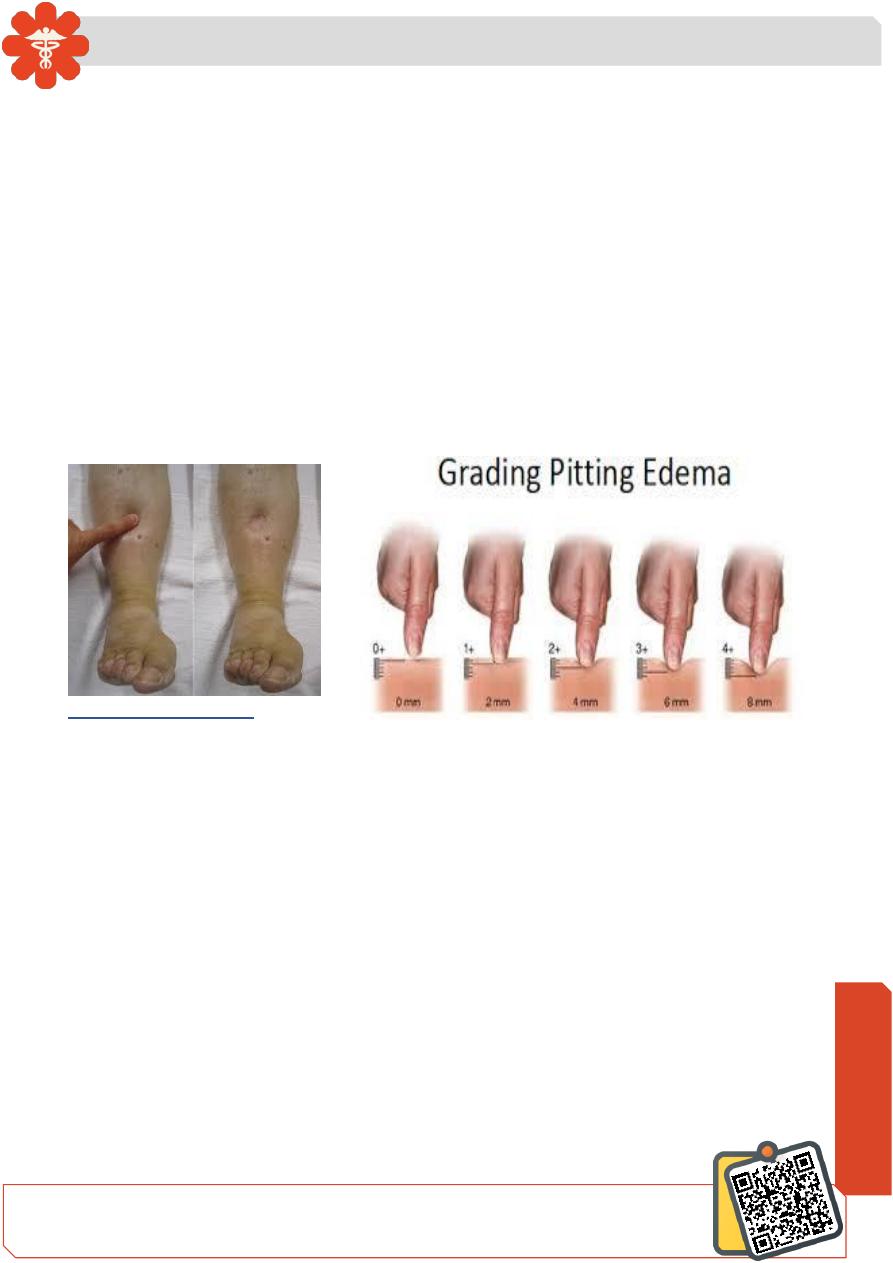

• Clinically, this can be detected by persistence of an indentation in tissue following

pressure on the affected area (pitting oedema).

Pitting oedema tends to accumulate in the ankles during the day and improves overnight

as the interstitial fluid is reabsorbed

Non-pitting oedema is typical of lymphatic obstruction and may also occur as the result

of excessive matrix deposition in tissues: for example, in hypothyroidism or systemic

sclerosis.

Clinical assessment

• Dependent areas, such as the ankles and lower legs, are typically affected first but

oedema can be restricted to the sacrum in bed-bound patients.

• With increasing severity, oedema spreads to affect the upper parts of the legs, the

genitalia and abdomen.

• Ascites is common and often an earlier feature in children or young adults, and in

liver disease.

Pleural effusions are common but frank pulmonary oedema is rare

• Facial oedema on waking is common. Features of intravascular volume depletion

(tachycardia, postural hypotension) may occur when oedema is due to decreased

oncotic pressure or increased capillary permeability.

• If oedema is localized – for example, to one ankle but not the other – then venous

thrombosis, inflammation or lymphatic disease should be suspected.

Need So

me

Help?

Medicine

Notes…

2

Investigations

• Oedema may be due to a number of causes , which are usually apparent from the

history and examination of the cardiovascular system and abdomen.

• Blood should be taken for measurement of urea and electrolytes, liver function and

serum albumin, and the urine tested for protein.

• Further imaging of the liver, heart or kidneys may be indicated, based on history

and clinical examination.

• Where ascites or pleural effusions occur in isolation, aspiration of fluid with

measurement of protein , albumin and glucose, and microscopy for cells, will

usually help to clarify the diagnosis in differentiating a transudate (typical of

oedema) from an exudate.

Medicine

Notes…

3

Management

• Mild oedema usually responds to elevation of the legs, compression stockings, or

a thiazide or a low dose of a loop diuretic, such as furosemide or bumetanide.

• In nephrotic syndrome, renal failure and severe cardiac failure, very large doses of

diuretics, sometimes in combination, may be required to achieve a negative sodium

and fluid balance.

• Restriction of sodium intake and fluid intake may be required.

• Diuretics are not helpful in the treatment of oedema caused by venous or lymphatic

obstruction or by increased capillary permeability.

• Specific causes of oedema, such as venous thrombosis, should be treated.

Ascites

• Ascites is accumulation of free fluid in the peritoneal cavity.

• Small amounts of ascites are asymptomatic, but with larger accumulations of fluid

(> 1 L) will cause abdominal distension, fullness in the flanks, shifting dullness on

percussion and, when the ascites is marked, a fluid thrill/fluid wave.

• Other features include eversion of the umbilicus, herniae, abdominal striae,

divarication of the recti and scrotal oedema.

• Dilated superficial abdominal veins may be seen if the ascites is due to portal

hypertension.

Medicine

Notes…

4

Pathophysiology

• Ascites has numerous causes, the most common of which are cirrhosis , malignant

disease and heart failure.

• Many primary disorders of the peritoneum and visceral organs can also cause

ascites, and these need to be considered even in a patient with chronic liver disease

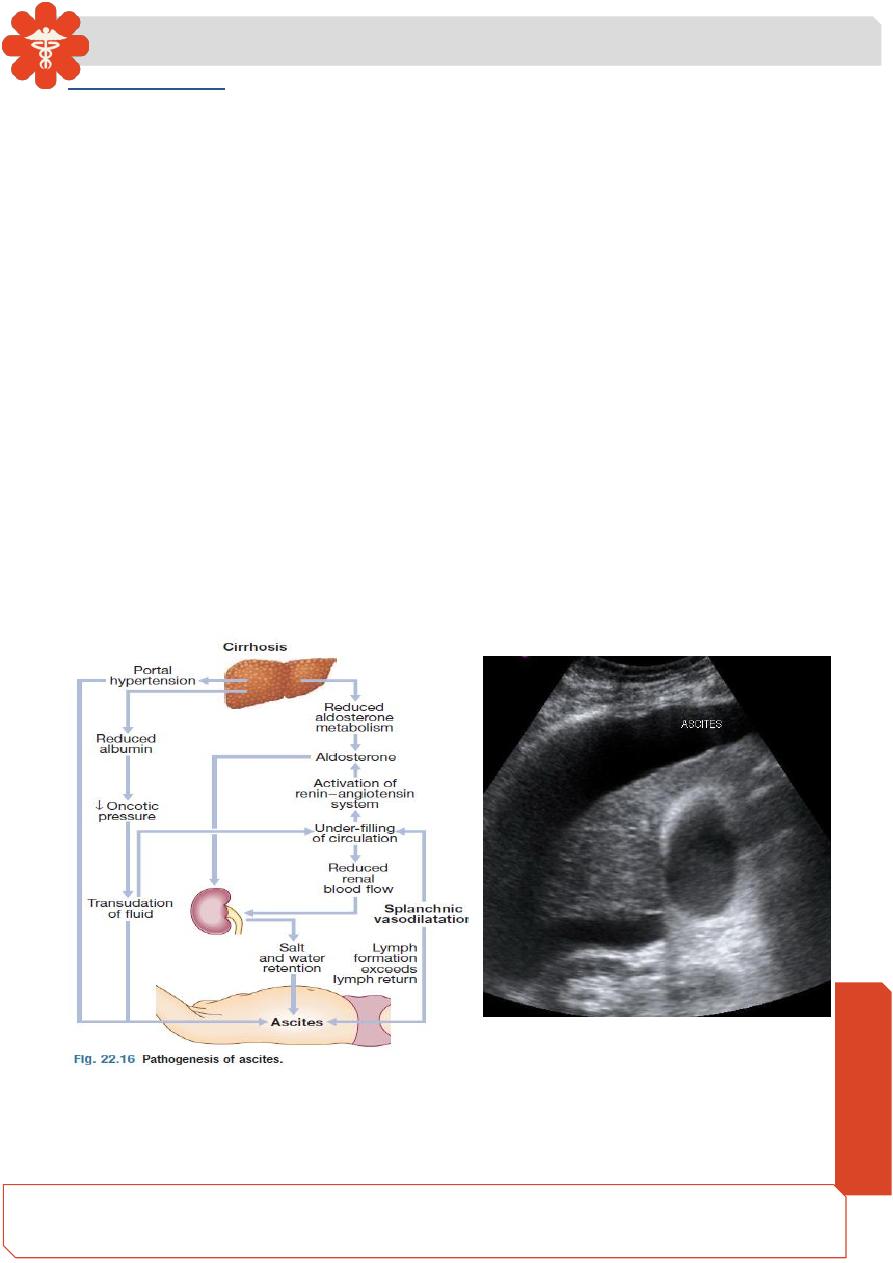

• Splanchnic vasodilatation is thought to be the main factor leading to ascites in

cirrhosis. This is mediated by vasodilators (mainly nitric oxide) that are released

when portal hypertension causes shunting of blood into the systemic circulation.

• Systemic arterial pressure falls due to pronounced splanchnic vasodilatation as

cirrhosis advances

• This leads to activation of the renin–angiotensin system with secondary

aldosteronism, increased sympathetic nervous activity, increased atrial natriuretic

hormone secretion and altered activityof the kallikrein

–kinin system . These

systems tend to normalize arterial pressure but produce salt and water retention.

• In this setting, the combination of splanchnic arterial vasodilatation and portal

hypertension alters intestinal capillary permeability, promoting accumulation of fluid

within the peritoneum.

Medicine

Notes…

5

Investigations

• Ultrasonography is the best means of detecting ascites, particularly in the obese and

those with small volumes of fluid.

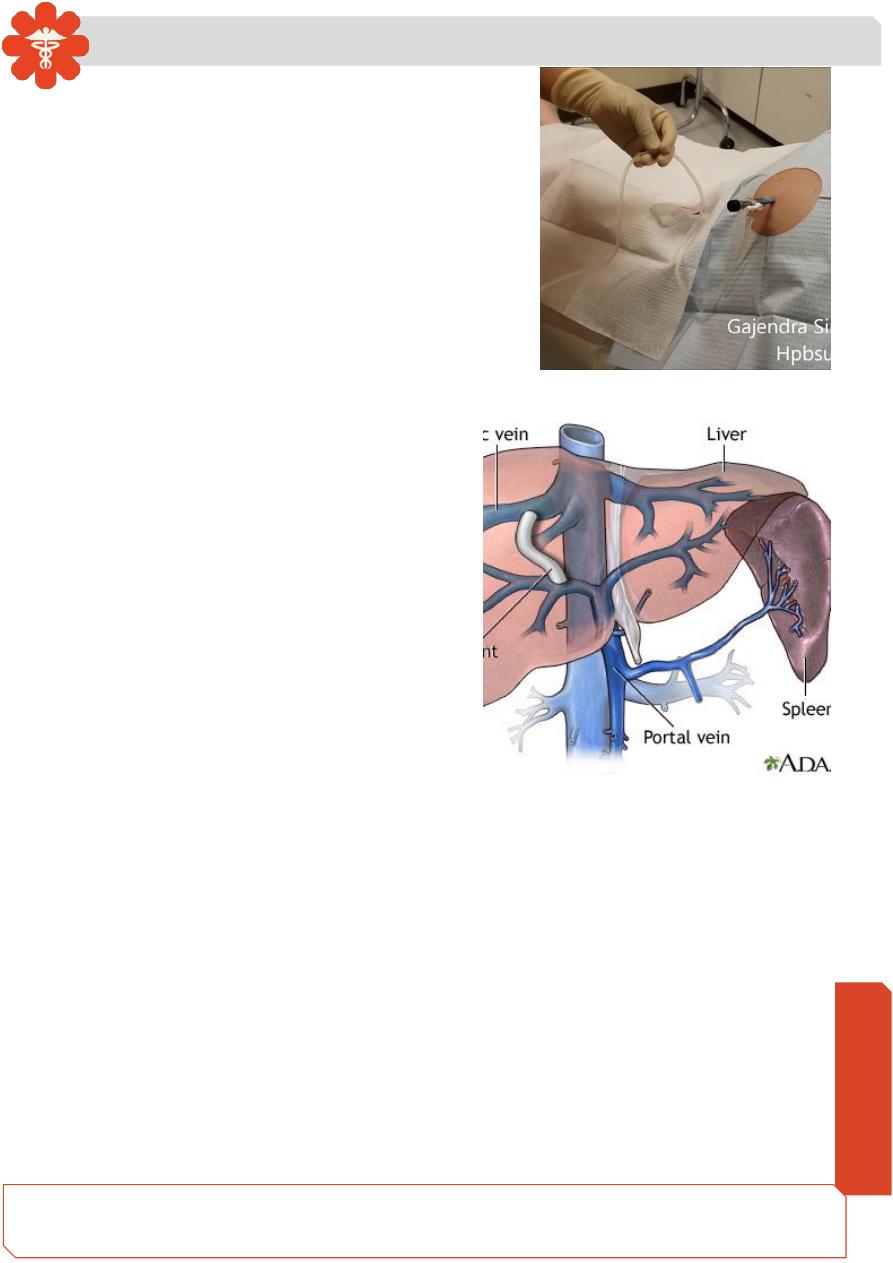

• Paracentesis (if necessary under ultrasonic guidance) can be used to obtain ascitic

fluid for analysis.

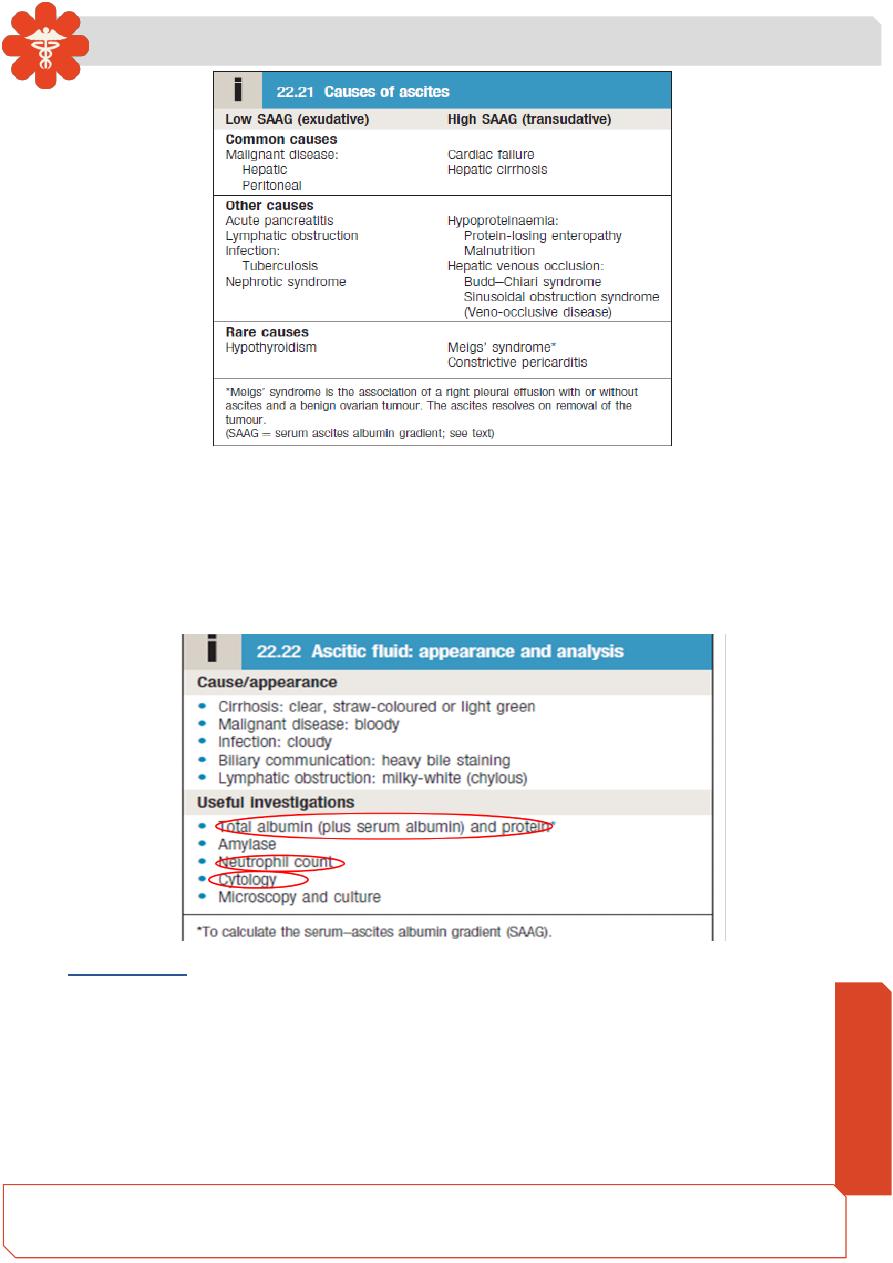

• The appearance of ascitic fluid may point to the underlying cause

• Pleural effusions are found in about 10% of patients, usually on the right side (hepatic

hydrothorax); most are small and identified only on chest X-ray, but occasionally a

massive hydrothorax occurs. Pleural effusions, particularly those on the left side,

should not be assumed to be due to the ascites.

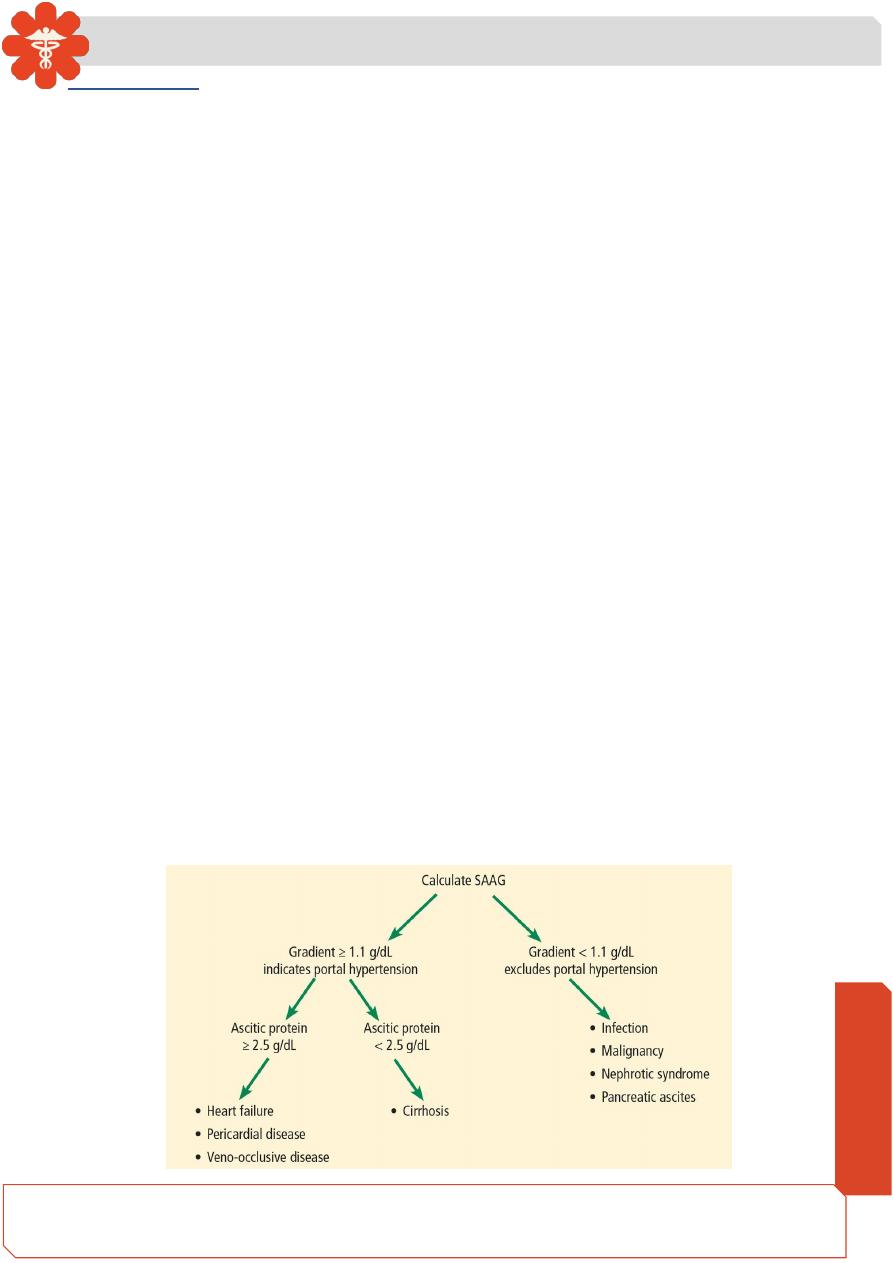

• Measurement of the protein concentration and the serum–ascites albumin gradient

(SAAG) can be a useful tool to distinguish ascites of different aetiologies.

• Cirrhotic patients typically develop ascites with a low protein concentration

(‘transudate’; protein concentration < 25 g/L (2.5 g/dL)) and relatively few cells.

• In up to 30% of patients, however, the total protein concentration is > 30 g/L (3.0 g/dL).

In these cases, it is useful to calculate the SAAG by subtracting the concentration of

the ascites fluid albumin from the serum albumin. A gradient of > 11 g/L (1.1 g/dL) is

96% predictive that ascites is due to portal hypertension.

• Venous outflow obstruction due to cardiac failure or hepatic venous outflow obstruction

can also cause a transudative ascites, as indicated by an albumin gradient of > 11 g/L

(1.1 g/dL) but, unlike in cirrhosis, the total protein content is usually > 25 g/L (2.5 g/dL).

• High protein ascites (‘exudate’; protein concentration > 25 g/L (2.5 g/dL) or a SAAG of

< 11 g/L (1.1 g/dL) raises the possibility of infection (especially tuberculosis),

malignancy, pancreatic ascites or, rarely, hypothyroidism.

Medicine

Notes…

6

• Cytological examination may reveal malignant cells (one-third of cirrhotic patients

with a bloody tap have a hepatocellular carcinoma).

• Polymorphonuclear leucocyte counts of > 250 × 106/L strongly suggest infection

(spontaneous bacterial peritonitis).

• Laparoscopy can be valuable in detecting peritoneal disease

Management

• Successful treatment relieves discomfort but does not prolong life; if over vigorous,

it can produce serious disorders of fluid and electrolyte balance, and precipitate

hepatic encephalopathy .

• Treatment of transudative ascites is based on restricting sodium and water intake,

promoting urine output with diuretics and, if necessary, removing ascites directly

by paracentesis.

Medicine

Notes…

7

• Exudative ascites due to malignancy is treated with paracentesis but fluid

replacement is generally not required. During management of ascites, the patient

should be weighed regularly.

•

Diuretics should be titrated to remove no more than 1 L of fluid daily, so body weight

should not fall by more than 1 kg daily to avoid excessive fluid depletion.

Sodium and water restriction

• Restriction of dietary sodium intake is essential to achieve negative sodium balance

and a few patients can be managed satisfactorily by this alone. Restriction of

sodium intake to 100 mmol/24 hrs (‘no added salt diet’) is usually adequate. Drugs

containing relatively large amounts of sodium, and those promoting sodium

retention, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), must avoided .

• Restriction of water intake to 1.0–1.5 L/24 hrs is necessary only if the plasma

sodium falls below 125 mmol/L.

Diuretics

• Most patients require diuretics in addition to

sodium restriction.

• Spironolactone (100–400 mg/day) is the first-line

drug because it is a powerful aldosterone

antagonist; it can, however, cause painful

gynaecomastia and hyperkalaemia, in which

case amiloride (5

–10 mg/day) can be substituted.

• Some patients also require loop diuretics, such as furosemide, but these can lead

to fluid and electrolyte imbalance and renal dysfunction.

• Diuresis may be improved if patients are rested in bed, perhaps because renal

blood flow increases in the horizontal position.

• Patients who do not respond to doses of 400 mg spironolactone and 160 mg

furosemide, or who are unable to tolerate these doses due to hyponatraemia or

renal impairment, are considered to have refractory or diuretic-resistant ascites and

should be treated by other measures.

Paracentesis

• First-line treatment of refractory ascites is large-volume paracentesis.

• Paracentesis to dryness is safe, provided the circulation is supported with an

intravenous colloid such as human albumin (6

–8 g per litre of ascites removed,

Medicine

Notes…

8

usually as 100 mL of 20% or 25% human

albumin solution (HAS) for every 1.5

–2 L of

ascites drained) or another plasma expander.

Paracentesis can be used as an initial therapy

or when other treatments fail.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt (TIPSS)

• A transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic

stent shunt can relieve resistant ascites

but does not prolong life; it may be an

option where the only alternative is

frequent, large volume paracentesis.

• TIPSS can be used in patients awaiting

liver transplantation or in those with

reasonable liver function, but can

aggravate encephalopathy in those with

poor function.