Injuries of the shoulder

Dr. Ammar Talib Al- YassiriCollege of Medicine / Baghdad University

Objectives

FRACTURES OF THE CLAVICLEFRACTURES OF THE SCAPULA

ACROMIOCLAVICULAR JOINT INJURIES

STERNOCLAVICULAR DISLOCATIONS

DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER

FRACTURES OF THE CLAVICLE

In childrenfractures easily

unites rapidly.

In adults

much more troublesome

common.

Fractures of the midshaft > lat. Fractures>med.fractures

Mechanism of injury

A fall on the shoulder or the outstretched hand

In the common mid-shaft fracture

In fractures of the outer end

Clinical features:

The arm is clasped to the chestA subcutaneous lump

it is prudent to feel the pulse and gently to palpate the root of the neck

Outer third fractures are easily missed or mistaken for acromioclavicular joint injuries.

Imaging:

requires at least an AP view and another taken with a 30 degree cephalic tilt.middle third of the bone

Fractures of the outer third may be missed

medial third fractures it is also wise to obtain x-rays of the sterno-clavicular joint

Classification:

Clavicle fractures are usually classified on the basis of their location:

Group I (middle third fractures),

Group II (lateral third fractures) and

Group III (medial third fractures).

Treatment:

MIDDLE THIRD FRACTURES:Non-operative management (sling for 1-3 WKs)LATERAL THIRD FRACTURES

minimally displaced : sling for 2–3 weeks

Displaced lateral third fractures: surgery

MEDIAL THIRD FRACTURES: non operatively

Complications

EARLYInjury to the vital structures,

a pneumothorax,

damage to the subclavian vessels and

brachial plexus injuries are all very rare.

LATE

Non-union:

Risk factors

increasing age,

displacement,

comminution

female sex.

Symptomatic non-unions are generally treated with plate fixation and bone grafting if necessary.

Malunion : All displaced fractures heal in a nonanatomical position with some shortening and angulation, however most do not produce symptoms.

Stiffness of the shoulder This is common but temporary; it results from fear of moving the fracture.

FRACTURES OF THE SCAPULA

Mechanisms of injury

The body of the scapula

The neck of the scapula

The coracoids process

Fracture of the acromion

Fracture of the glenoid fossa

Clinical features

The arm is held immobilesevere bruising over the scapula or the chest wall.

fractures of the body of the scapula are often associated with severe injuries to the chest, brachial plexus, spine, abdomen and head.

Careful neurological and vascular examinations are essential

X-Ray:

a comminuted fracture of the body of the scapula,a fractured scapular neck with the outer fragment pulled downwards by the weight of the arm.

Occasionally a crack is seen in the acromion or the coracoid process.

CT is useful for demonstrating glenoid fractures or body fractures

Treatment

Body fractures:Isolated glenoid neck fractures

Intra-articular fractures if displaced, >1/3 of the glenoid surface and is displaced by >5 mm surgical fixation should be considered.

Fractures of the acromion

Undisplaced fractures are treated non-operatively.

Displaced fracture require operative intervention to restore the anatomy.

Fractures of the coracoid process

distal to the coracoacromial ligaments (conservative)

proximal to the ligaments (operative)

Combined fractures ‘floating shoulder’ At least one of the injuries (and sometimes both) will need operative fixation

ACROMIOCLAVICULAR JOINT INJURIES

Mechanism of injury: A fall on the shoulder with the arm adducted

Pathological anatomy and classification:

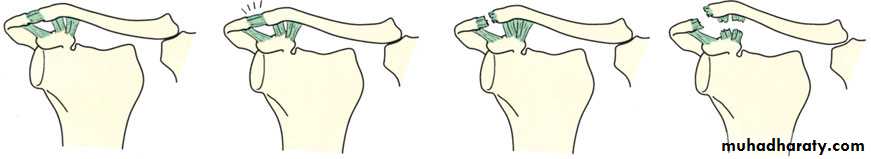

Type I

Type II

Type III

Type IV

Type V

Type VI

Clinical features:

point to the site of injuryarea may be bruised.

If there is tenderness but no deformity, the injury is probably a sprain or a subluxation.

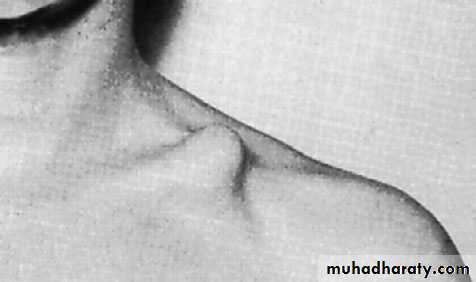

With dislocation the patient is in severe pain and a prominent ‘step’ can be seen and felt.

Shoulder movements are limited.

X-ray:

anteroposterior,cephalic tilt and are advisable.

axillary views

a stress view is sometimes helpful in distinguishing between a Type II and Type III injury:

Treatment:

Sprains and subluxations the arm is rested in a sling until pain subsides (usually no more than a week) and shoulder exercises are then begun.conservative treatment for a straight forward Type III injury.

Operative repair should be considered only for

patients with extreme prominence of the clavicle,

those with posterior or inferior dislocation of the clavicle and

those who aim to resume strenuous overarm or overhead activities.

STERNOCLAVICULAR DISLOCATIONS

Mechanism of injury:uncommon injury

lateral compression of the shoulders;

rarely, it follows a direct blow to the front of the joint.

Anterior dislocation is much more common than posterior.

The joint can be sprained, subluxed or dislocated.

Clinical features:

Anterior dislocation

prominent bump over the sternoclavicular joint.

painful

no cardiothoracic complications.

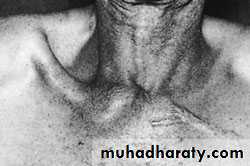

Posterior dislocation, though rare, is much more serious.

Discomfort is marked; there may be pressure on the trachea or large vessels, causing venous congestion of the neck and arm and circulation to the arm may be decreased.

X-Ray: plain x-rays are difficult to interpret. Special oblique views are helpful and CT is the ideal method.

Treatment:

Anterior dislocationPosterior dislocation should be reduced as soon as possible.

After reduction, the shoulders are braced back with a figure-of-eight bandage, which is worn for 3 weeks.

DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER

AETIOLOGY: Of the large joints, the shoulder is the one that most commonly dislocates. This is due to a number of factors:the shallowness of the glenoid socket;

the extraordinary range of movement;

underlying conditions such as ligamentous laxity or glenoid dysplasia; and

the sheer vulnerability of the joint during stressful activities of the upper limb.

ANTERIOR DISLOCATION

Mechanism of injury:

Dislocation is usually caused by a fall on the hand.

The head of the humerus is driven forward, tearing the capsule and producing avulsion of the glenoid labrum (the Bankart lesion). Occasionally the posterolateral part of the head is crushed

Clinical features:

Pain is severe.The patient supports the arm with the opposite hand and is loathe to permit any kind of examination.

The lateral outline of the shoulder may be flattened and,

The arm must always be examined for nerve and vessel injury before reduction is attempted.

X-Ray:

The anteroposterior x-ray will show the overlapping shadows of the humeral head and glenoid fossa, with the head usually lying below and medial to the socket.A lateral view aimed along the blade of the scapula will show the humeral head out of line with the socket.

Treatment:

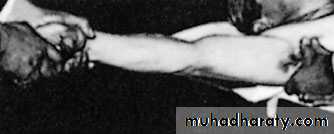

In a patient who has had previous dislocations, simple traction on the arm may be successful. Usually, sedation and occasionally general anaesthesia is required. With

Stimson’s technique,

Hippocratic method,

Kocher’s method,

An x-ray is taken to confirm reduction and exclude a fracture.

When the patient is fully awake, active abduction is gently tested to exclude an axillary nerve injury and rotator cuff tear. The median, radial, ulnar and musculocutaneous nerves are also tested and the pulse is felt.

The arm is rested in a sling for about three weeks in those under 30 years of age (who are most prone to recurrence) and for only a week in those over 30 (who are most prone to stiffness).

Then movements are begun, but combined abduction and lateral rotation must be avoided for at least 3 weeks.

Complications

EARLY:Rotator cuff tear:

Nerve injury: The axillary nerve is most commonly injured. Occasionally the radial nerve, musculocutaneous nerve, median nerve or ulnar nerve can be injured.

Vascular injury: The axillary artery may be damaged, particularly in old patients with fragile vessels.

Fracture-dislocation:

LATE

Shoulder stiffness

Unreduced dislocation:

Recurrent dislocation:

POSTERIOR DISLOCATION OF THE SHOULDER

rare, accounting for < 2 % of all dislocations around the shoulder.

Mechanism of injury:

Indirect force producing marked internal rotation and adduction

Posterior dislocation can also follow a fall on to the flexed, adducted arm.

Clinical features: The diagnosis is frequently missed

The arm is held in internal rotation and is locked in that position.

The front of the shoulder looks flat with a prominent coracoid, but

swelling may obscure this deformity;

seen from above, however, the posterior displacement is usually apparent.

X-Ray:

AP film (like an electric light bulb), (the ‘empty glenoid’ sign).A lateral film and axillary view is essential; it shows posterior subluxation or dislocation and sometimes a deep indentation on the anterior aspect of the humeral head.

Treatment:

The acute dislocation is reduced (usually under general anaesthesia)If reduction feels stable the arm is immobilized in a sling; otherwise the shoulder is held widely abducted and laterally rotated in an airplane type splint for 3–6 weeks to allow the posterior capsule to heal in the shortest position.

Shoulder movement is regained by active exercises.

Complications

Unreduced dislocation:

At least half the patients with posterior dislocation have ‘unreduced’ lesions when first seen up to two thirds of posteriordislocations are not recognised initially.

Typically the patient holds the arm internally rotated; he cannot abduct the arm more than 70–80 degrees, and if he lifts the extended arm forwards he cannot then turn the palm upwards.

If the patient is young, or is uncomfortable and the dislocation fairly recent, open reduction is indicated. Late dislocations, especially in the elderly, are best left, but movement is encouraged.

Recurrent dislocation or subluxation: Chronic posterior instability of the shoulder is discussed later