LECTURE TWO

ORAL SURGERY“CASE SHEET, ARMAMENTARIUM, AND PRINCIPLES OF ORAL SURGERY”

Dr. Mohammed Amjed

BDS, MSc, PhD

3.11.2015

Diagnosis, the key to understanding and treating disease, is a systematic process by which we uncover the identity of a patient's problem, leading to reliable predictions of its behaviour and possible therapy.

● The process is a detective story in which the information obtained is matched with patterns of known disease.

● A standard framework is used to record findings and acts as a checklist and an aid to communication between colleagues.

● Special investigations may be required to lead you to a definitive diagnosis, which must relate directly to the reason for attendance (chief complain).

● A treatment plan should be based on the diagnosis and agreed with the patient.

● The diagnosis or identity of a disease is used— to predict its behavior or natural history

— to plan treatment— to support the patient in understanding their condition

— to link similar cases for research purposes

— to enable communication between professionals

Why is the diagnosis?

RECORD KEEPING

The following sections are divided according to commonly used subdivisions in a patient record.The concept of this progression and the written record certainly help to keep one’s thoughts in a logical order.

Demographic details (Personal information)

The patient’s full name, address, date of birth, gender, ethnic origin and marital status should be recorded.PRESENTING COMPLAINT (CHIEF COMPLAIN)

• Write the complaint in the patient’s own words,

• Ensure you put it in inverted commas—for example, ‘I’ve pain in upper right jaw area’. Complaints can be multiple and should be dealt with one at a time.Listen first and listen second

Listening does not just involve using your ears.

Also use facial expression,body language

and verbal fluency to help understand what is really troubling someone and to suggest other areas in which the history might need to proceed.

Remember that speech is not the only means of communicating. Make full use of communication aids such as picture boards, drawings done by the patient showing where the pain is, when this is a more appropriate form of discourse.

What questions used during history taking ?

Open questions- These are seen as the gold standard of historical inquiry. They do not suggest a 'right' answer to the patient. It give patients a chance to express what is on their mind. Examples include questions such as 'How are you?'. There are other similar open questions but it may be effective just to let the patient start speaking sometimes.

• Open questions can be used to obtain specific information about a particular symptom as well. For example: 'Tell me about your cough'.

• Open questions cannot always be used, as sometimes you will need to delve deeper and obtain discriminating features about which the patient would not be aware.

Questions with options

Sometimes it is necessary to 'pin down' exactly what a patient means by a particular statement.

In this case, if the information you are after cannot be obtained through open questioning then give the patient some options to indicate what information you need.

Leading questions

These are best avoided if at all possible. They tend to lead the patient down an avenue that is framed by your own assumptions.For instance, a male patient presents with episodic chest pain. You know he is a smoker and overweight so you start asking questions that would help you to decide if it's angina. So you ask: 'Is it worse when you're walking?', 'Is it worse in cold or windy weather?'. The patient is not sure of the answer, not having thought of the influence of exercise or the weather on his pain, but answers yes, remembering a cold day when walking the dog when the pain was bad. You may be off on the wrong track and find it hard to get back from there. It is much better to ask an open question such as: 'Have you noticed anything that makes your pain worse?'. When the patient answers: ‘some food types', you are on firmer ground in suspecting that this may be chest pain of gastrointestinal origin.

History of presenting illness

Record the history chronologically, beginning with the onset and detailing the progress of the complaint to the present day.In oral surgery the common complaints are of pain, swelling or lump, or ulcer.

Allow the patient to tell the story in her or his own way and do not ask leading questions. Main points to cover include:● What was the first thing that was noticed?

● Are there any other symptoms?● What is the main trouble today?

● Does anything worsen or improve the symptoms?

● Does the complaint incapacitate the patient (i.e. does it stop the patient from sleeping, working, eating, carrying out normal activities)?

It is important to note recurrence of problems. For example, wisdom tooth infections may settle spontaneously, but tend to recur at intervals of weeks to

months, whereas malignant tumours tend to be relentlessly progressive.

Medical history

• It is essential in order to assess the fitness of the patient for any potential procedure.

• The history will also help to warn you of any emergencies that could arise.

• Possible contribution to the diagnosis of the presenting complaint.

The medical history should be reviewed systematically.

In physical medicine it is common, after initial open questions about the patient’s general health, to ask questions in relation to each body system in turn:

cardiovascular, respiratory, CNS, gastrointestinal tract (including the liver), genitourinary tract (including the kidneys), etc.

It is essential also to ask specific questions about drug therapy, allergies and abnormal bleeding.

Social history

Occupation, home circumstances and travelling arrangements should be reviewed so they can be used to help formulate the details of the treatment plan.For example, planning third molar surgery as an outpatient, for a parent with small children, with a one-hour journey to the surgery by public transport, returning to an empty house would be unsympathetic and unwise as the patient would have difficulty in dealing with postoperative complications such as haemorrhage or fainting.

Smoking and alcohol consumption should also be considered under this heading.

Past dental historyIf the patient is new to your practice then you should note details of previous attendance and treatment.

This would include the name and address of their previous practitioner, frequency of attendance and any problems relevant to the presenting complaint.

The reason for discontinuing attendance at that practice should also be noted.

In case of tooth extraction, ask about the difficulty of the last extraction if any, and the postoperative bleeding.

● Character

● Severity● Site

● Radiation (spread)

● Onset

● Duration

● Periodicity

● Aggravating factors

● Relieving factors

● Associated phenomena

Features of pain worth noting in the history

EXAMINATION

There are two ways of approaching the examination.-You may look at the site of complaint first and subsequently carry out extraoral and intraoral examination.

-Alternatively you may do a systematic extraoral

examination followed by a systematic intraoral examination, which will encompass the area of complaint.Extraoral examination

The general appearance of the patient should be considered.

Do they look ill or well; are they anxious?

Note the skin complexion and mucosal colour for signs of anaemia or jaundice.

Assess the body in general and the head and neck for signs of deformity or asymmetry.

In trauma cases look carefully for lacerations and abrasions.

Look systematically at, or for:

● lymph nodes: these should be palpated for enlargement or change in texture● TMJ function & trismus: defined as limitation of mouth opening of musculoskeletal origin, trismus can be partial or complete. Normal mouth opening is at least 40 mm

● rima oris (oral entrance): a small mouth opening can make surgery difficult. Limitation could be due to scarring or the patient may naturally have a small mouth

● swellings or deformity.

Intraoral examination

The size of the oral cavity and the distensibility of the soft tissues should be noted.The soft tissues should then be examined in sequence, and this sequence should always be used by that clinician, so no area is omitted. A suggested sequence is:

● buccal sulci (upper and lower)

● floor of the mouth

● tongue (dorsal and ventral surfaces)

● palate (hard and soft)

● oropharynx

● gingivae.

Next, the teeth may be examined and charted .

The surgical or problem area (offending tooth) should now be examined.

Redness or swelling or inflammation should be noted, as should any discharge of pus. Look specifically for ulceration, erosion or keratosis of mucosal surfaces and for any lumps or deformity.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

When many diagnoses might explain the signs and symptoms of the chief complaint, a differential diagnosis is made.This is a list of possible diagnoses written in order of probability.

It is unhelpful to arrange special tests unless there is a list of different possible diagnoses that must be distinguished.● Duration

● Change in size● Any possible cause

● Exact anatomical site

● Associated lymph nodes

● Single or multiple

● Shape

● Size

● Colour

● Definition of periphery

● Consistency

● Warmth

● Tenderness

● Attachment to skin

● Attachment to deeper structures

● Fluctuance

● Inflammation

● Pulsation

● General well-being of the patient

FEATURES WORTH NOTING DURING HISTORY AND EXAMINATION OF A LUMP OR SWELLING

Features worth noting on examination of an ulcer

● Anatomical location● Single or multiple

● Size

● Shape

● Base

● Edge

● Adjacent tissues

● Discharge

● Is it painful?

● General condition of the patient

FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Often the history and clinical examination are not sufficient to clarify the diagnosis and enable a sound treatment plan to be drawn up. Further investigation might involve a wide range of measures, such as:

● haematological investigations

● microbial culture

● temperature, pulse, respiratory rate, blood pressure, weight

● urinalysis

● biopsy—incisional or excisional.

● radiography and other imaging

● vitality tests

CONSENT

All patients must be fully informed before any decisionconcerning treatment is made and no treatment should be performed without a patient’s full consent.

Surgery is regarded as an assault on the body. Adults

may give consent to such a process, but cannot be regarded as having consented if they do not fully understand the implications.What a patient should be told should be influenced by what a reasonable patient could be expected to want to know. This is difficult to judge, so it is proper to offer more rather than less information.

- For example, surgery for an impacted wisdom tooth has potential complications of pain, swelling, trismus, altered sensibility of the lip and/or tongue.

- Patients should also be advised as to the likelihood of incidence, the approximate extent and probable duration of each of the problems.

- For patients under 16 years of age it is generally accepted that a parent or legal guardian will give consent on the child’s behalf. Consent may be withdrawn at any time. The patient’s wishes must be respected.

ARMAMENTARIUM FOR BASIC ORAL SURGERY

CONTENTS

Instruments for Transferring Sterile InstrumentsInstruments for Incising Tissue

Instruments for Elevating Mucoperiosteum

Instruments for Retracting Soft Tissue

Instruments for Controlling Hemorrhage

Instruments for Grasping Tissue

Instruments for Removing Bone

Instruments for Removing Pathologic Tissue

Instruments for Suturing Mucosa

Instruments for Holding the Mouth OpenInstruments for Suctioning

Instruments for Irrigating

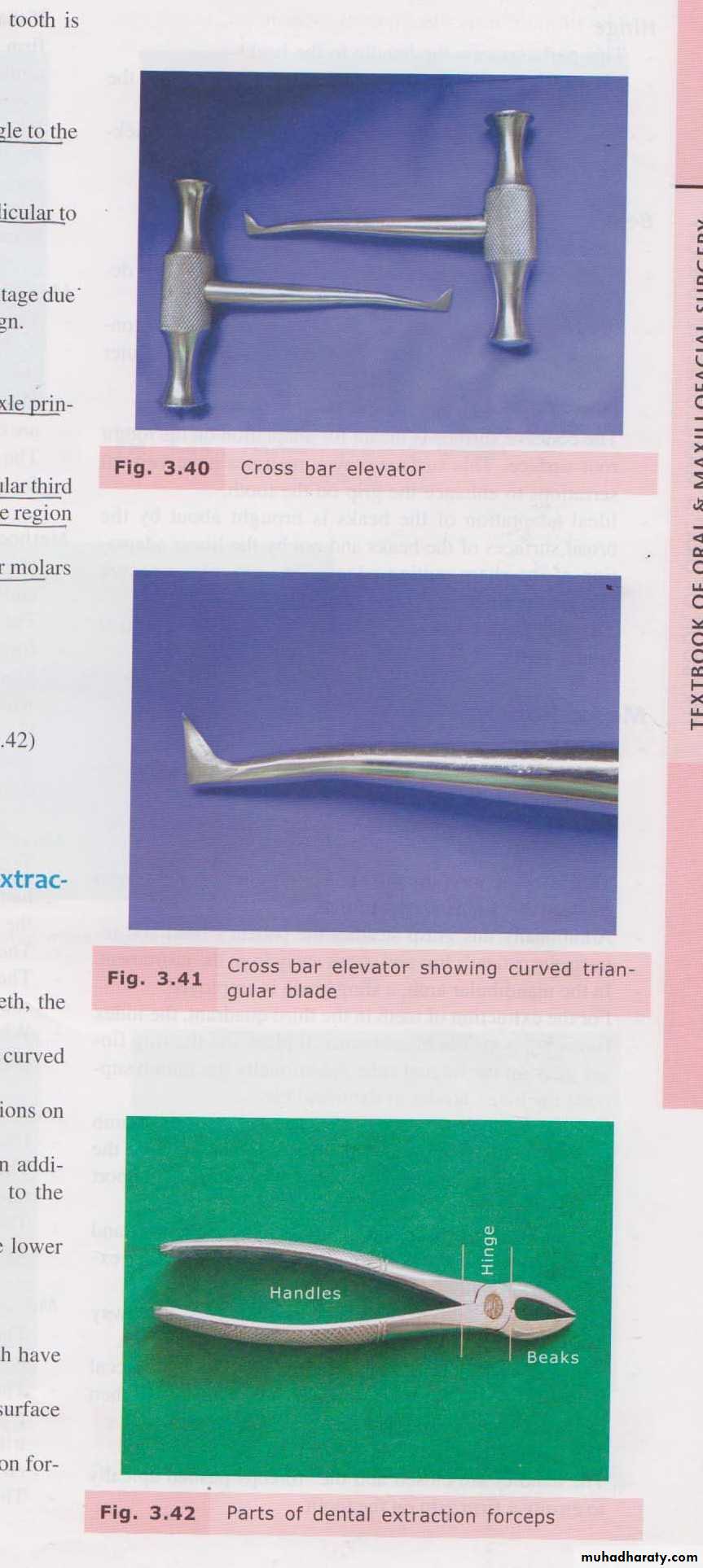

Instruments for Extracting the Teeth

-Local Anesthetic instruments

-Dental elevators

-Extraction forceps

Instrument trays

INSTRUMENTS FOR TRANFERRING STERILE INSTRUMENTS

CHEATLE FORCEPS

Long handlesLong, angulated beaks: serrated

Beaks: dipped in antiseptic solution

Lift up sterile instruments from autoclave/ drum

INSTRUMENTS FOR INCISING TISSUE

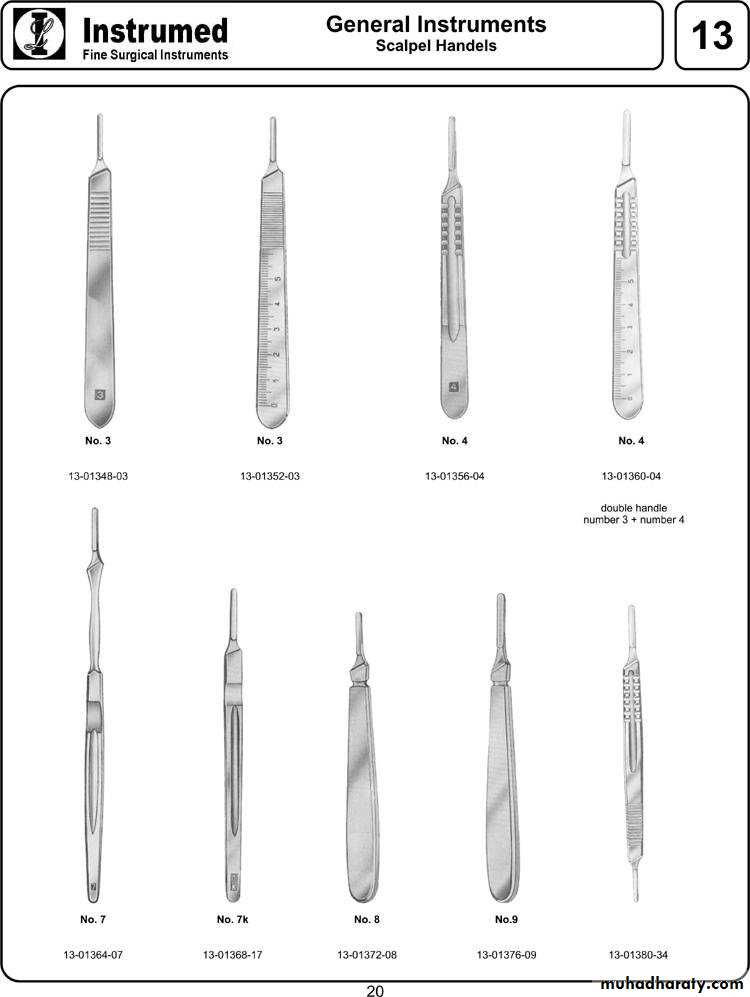

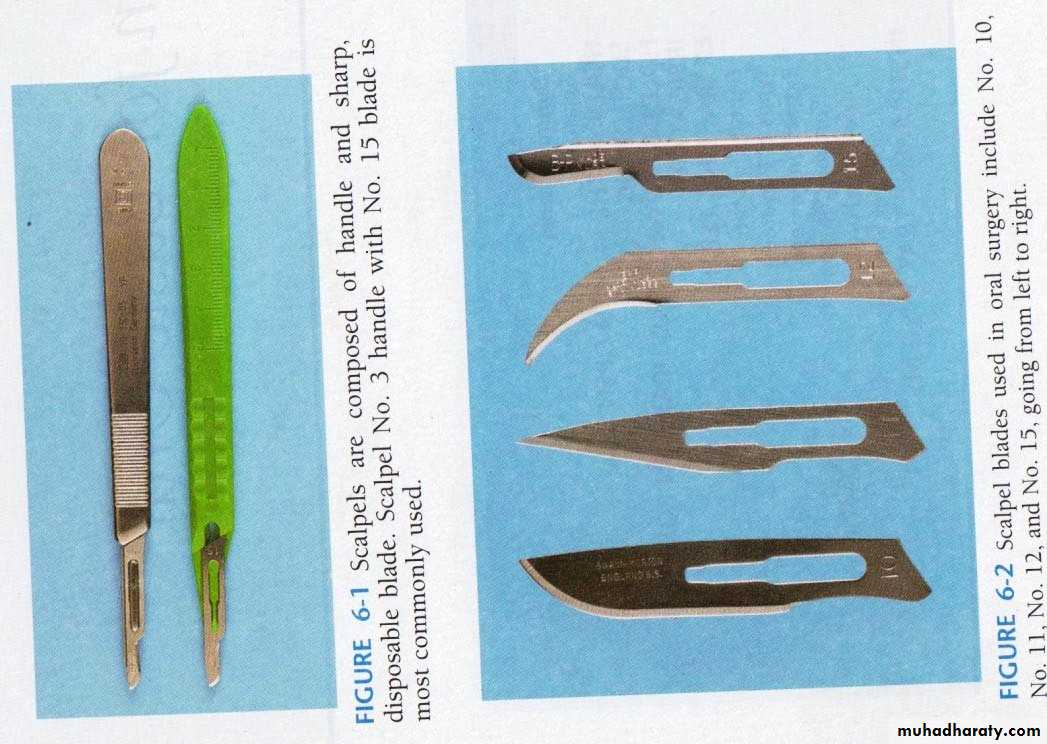

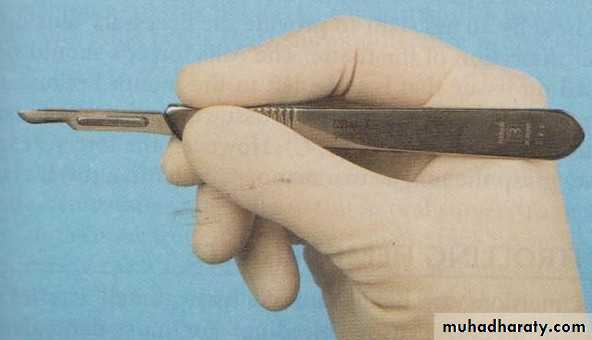

SCALPEL:Handle like No. 3, No.7

Differently shaped

2. No.10- similar to No.15

Large skin incisions

3.No. 11

Sharp, pointed

Incising an abscess

4.No.12

Hooked

Operculectomy

Posterior aspect of teeth/maxillary tuberosity

Disposable, sterile sharp blade

• 1. No.15- most commonly usedRelatively small

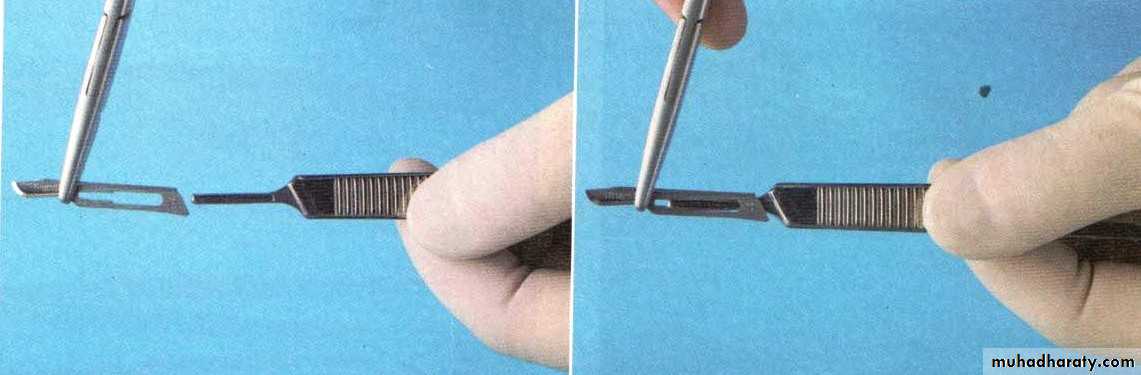

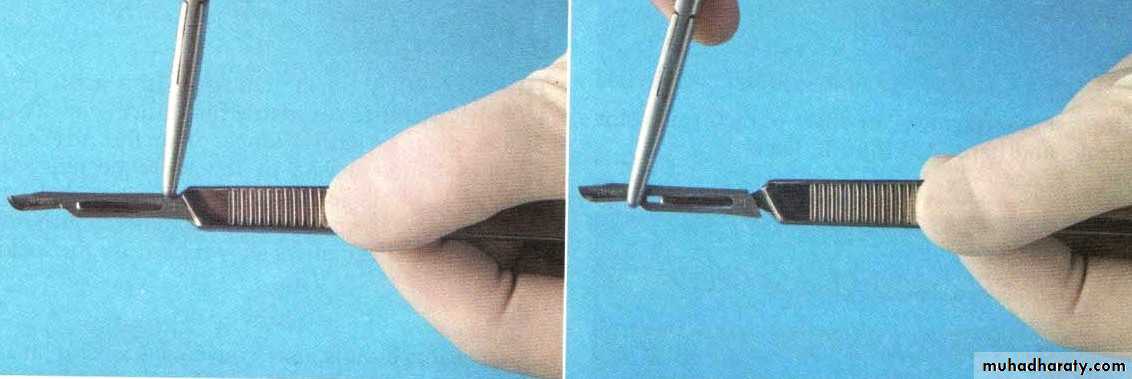

Blade loaded

Blade removedPen Grasp: Allow maximal control

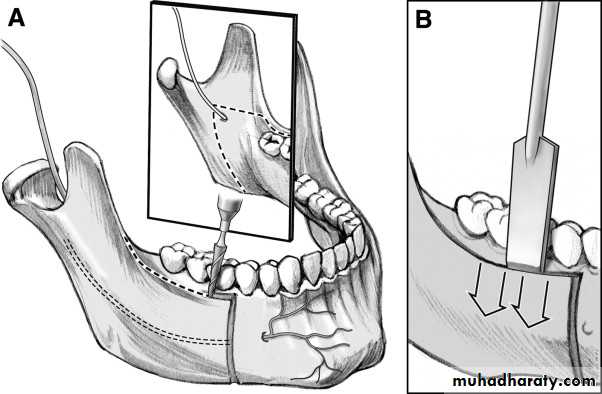

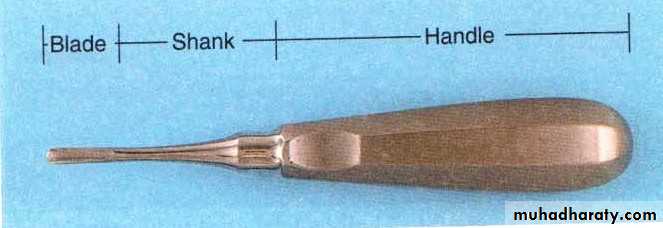

Hold mobile tissue firmlyINSTRUMENTS FOR ELEVATING MUCOPERIOSTEUM

Mucosa & Periosteum reflected in single layer: Periosteal Elevator• No.9 Molt periosteal elevator

sharp, pointed end: reflect papillae from between teeth, loosen soft tissues via gingival sulcus

Broader, flat end: elevating the tissue from bone

Thin, sharp cutting edge- clean separation of periosteum from bone

Also used as retractor

II. Howarth’s Periosteal Elevator

Double-endedOne end: flat, broad, spatulate- sharp edge

Other end: Rugine end; flat & rectangular. Small tip – sharp projection perpendicular

INSTRUMENTS FOR RETRACTING SOFT TISSUE

Good vision & accessCheeks, tongue & mucoperiosteal flaps

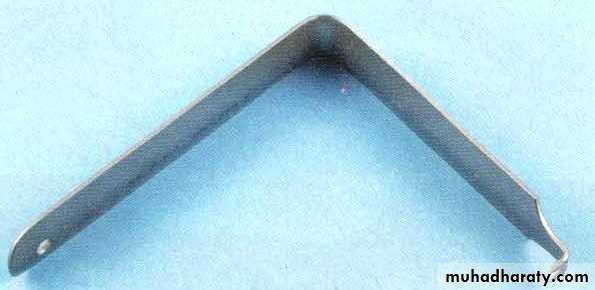

Right angle Austin retractor

‘L’-shaped- no handleRetraction of small intraoral flaps: removal of impacted teeth

Offset broad Minnesota retractor

Both Austin’s & Minnesota : retract cheek & mucoperiosteal flap simultaneouslyLangenback’s Retractor

‘L’ shaped retractor- long handleRetraction of flap edges : improved visualization of deeper layers & structures

Different sizes: handle length & blade width

Tongue Depressor

‘L’- shapedBroad, flat, rounded blade

Retraction & depression of tongue

Improve visibility- posterior pharyngeal wall & tonsillar region, lingual side of mandible

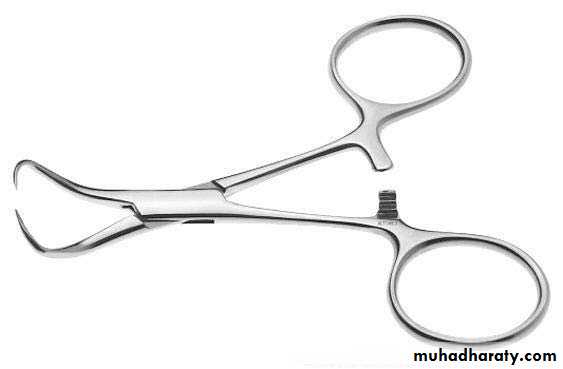

INSTRUMENTS FOR CONTROLLING HEMORRHAGE

Arteries & veins- bleeding : pressure not enoughHemostat

Variety of shapes

Small or delicate/ Larger

Straight/ Curved

Curved hemostat- common

Long, delicate beak to grasp tissue & a locking handle

Locking handle: clamps onto a vessel; then let go & remains clamped onto tissue

Removes granulation tissuePicks up root tips, pieces of calculus, fragments of amalgam restorations, any other small

particles dropped into the mouth

Small hemostat: Mosquito forceps

INSTRUMENTS FOR GRASPING TISSUE

Used for Soft tissue stabilization- pass suture needleCollege/Cotton forceps

AngledSmall fragments of tooth/amalgam/foreign material

Placing/removing gauze packs

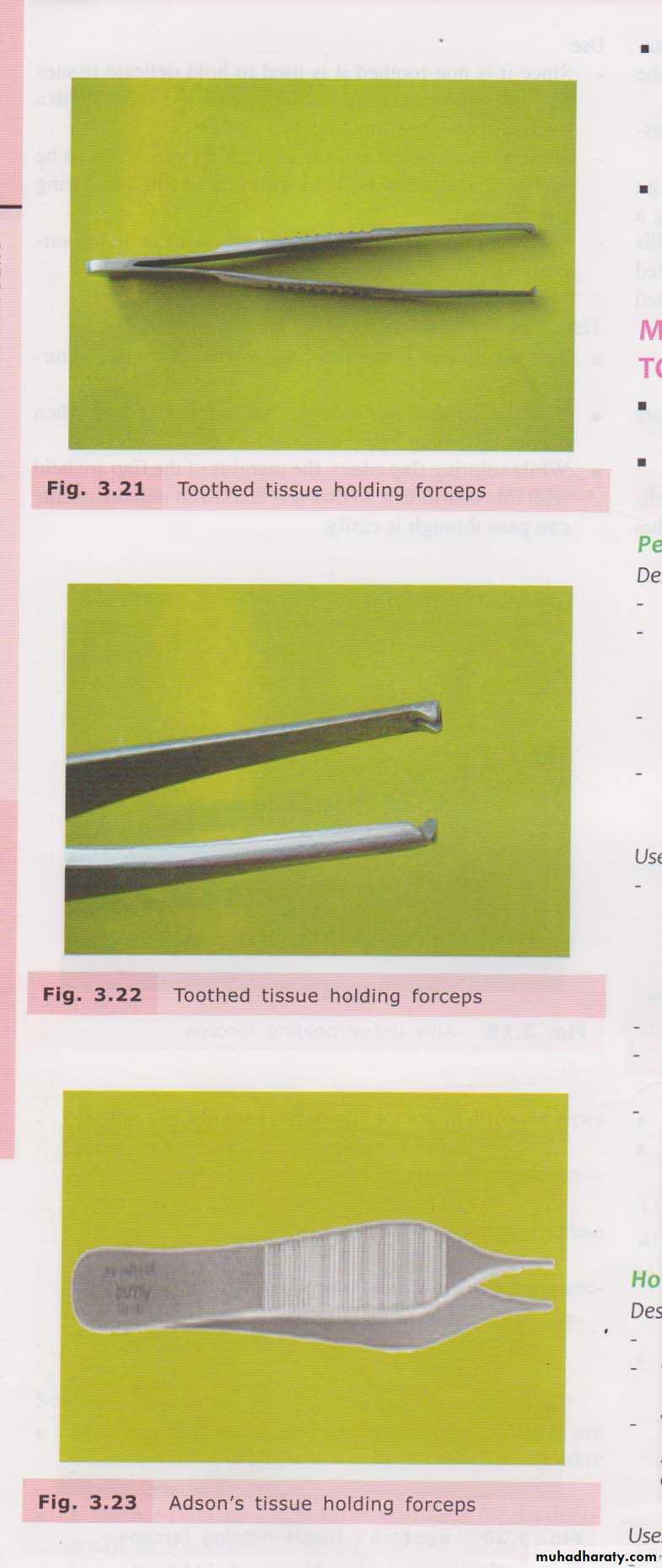

Tissue Holding Forceps

Toothed/ Non- toothedToothed: periosteum, muscle, aponeurosis

Non- toothed: fascia, mucosa, pathological tissues

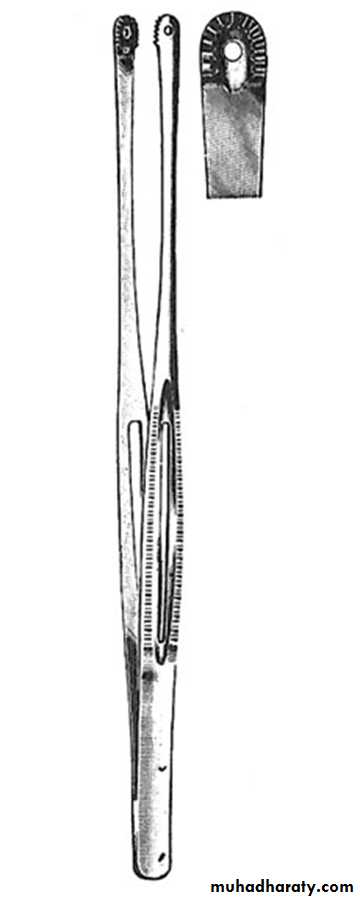

Allis Tissue forceps

Allis Tissue forcepsLocking handles

- proper placement

- held by asstisstant :necessary tension

Teeth which will firmly grip the tissue

Removal of large amounts of fibrous tissue: Epulis fissuratum

Russian Tissue forceps

Large, round-endedTeeth elevated from sockets

Round end: positive grip, avoids slippage; unlike hemostat

Placement of gauze: isolation

INSTRUMENTS FOR REMOVING BONE

Rongeur forcepsMost commonly used

Sharp blades- squeezed together; cutting/pinching through bone

Leaf spring between the handle : instrument opens when hand pressure is released

Repeated cuts without manually reopening

2 major designs:

Side-cuttingSide-cutting & end-cutting

Do not :

-remove large amounts of bone in single bites

- use to remove teeth

Small amounts- multiple bites

Success: sharpness- sharpen before sterilisation

Carbide tips- use more than once, before sharpeningCylindrical handle- serrated with flat end: struck with mallet

Flat & rectangular: cutting edge in different sizes

Single bevel- cutting edge

Transalveolar extraction/ removal of impacted tooth

Shape/ contour irregular bony surfacesBevel faces- bone to be cut

Cutting edge- perpendicular to bone

Chisel

OsteotomeSplitting bone

Cylindrical handle- serrated for good grip

Flat end- tapped with mallet

Flat & rectangular blade

Bibivelled cutting edge- converge to a sharp edge

Osteotomy cuts: orthognathic surgery/ refracturing malunited fractures

Osteoplasty/ bone recontouringSplit impacted tooth for easy removal

Surgical Mallet

Cutting bone with osteotome/ chiselStainless steel- strong cylindrical handle

Tapped : ‘pull-back’ action- force from wrist

Fracture jaw: inadvertent force

Bone file

Final smoothing of bone before suturing of mucoperiosteal flapDouble-ended: small & large

Removes bone: pull stroke

Avoid push motion- burnishing & crushing the bone

Bur and Handpiece

Surgical removal of teethHigh-speed + sharp carbide burs: cortical bone removal

Completely sterilizable in a steam autoclave: ensure on purchase

Relatively high speed & torque: rapid bone removal & efficient sectioningMust not exhaust air into the operative field

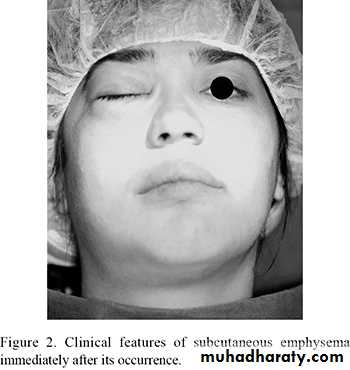

Avoid high-speed turbine drills used in restorative dentistry (tissue emphysema)

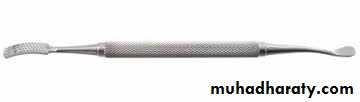

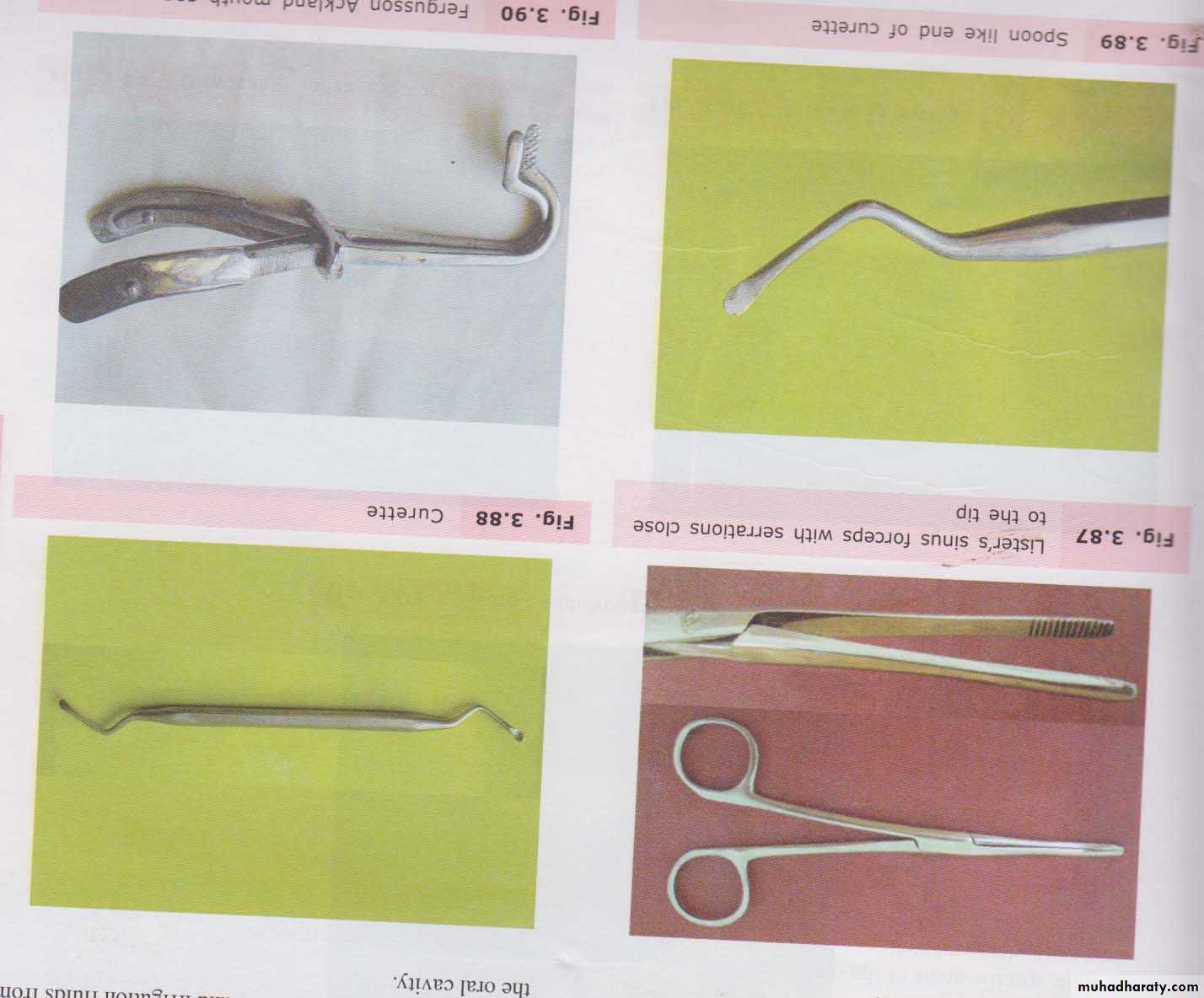

INSTRUMENTS FOR REMOVING PATHOLOGICAL TISSUE

Periapical CuretteAngled, double-ended

Removal of granulomas/small cysts from periapical lesions

Small amounts of granulation tissue debris from tooth sockets

Sinus Forceps

Handles with rings at the endNo lock/ ratchet

Narrow, long, slender beaks

Inner surface- transverse striations: close to the tip

Draining pus from an abscess

Inserted by blunt dissection & opened up

No lock: blind insertion & closure- injure structures

INSTRUMENTS FOR SUTURING MUCOSA

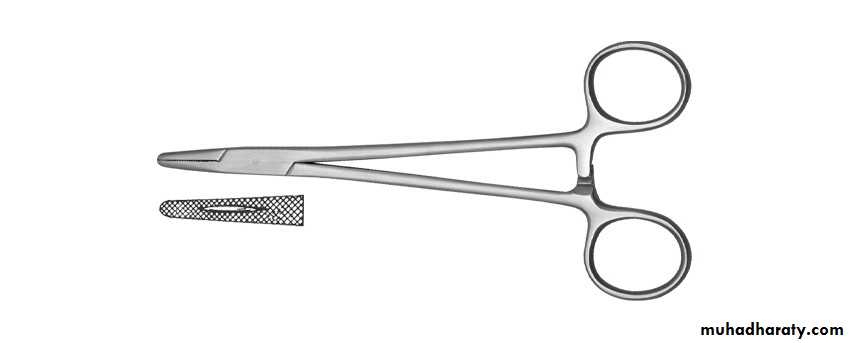

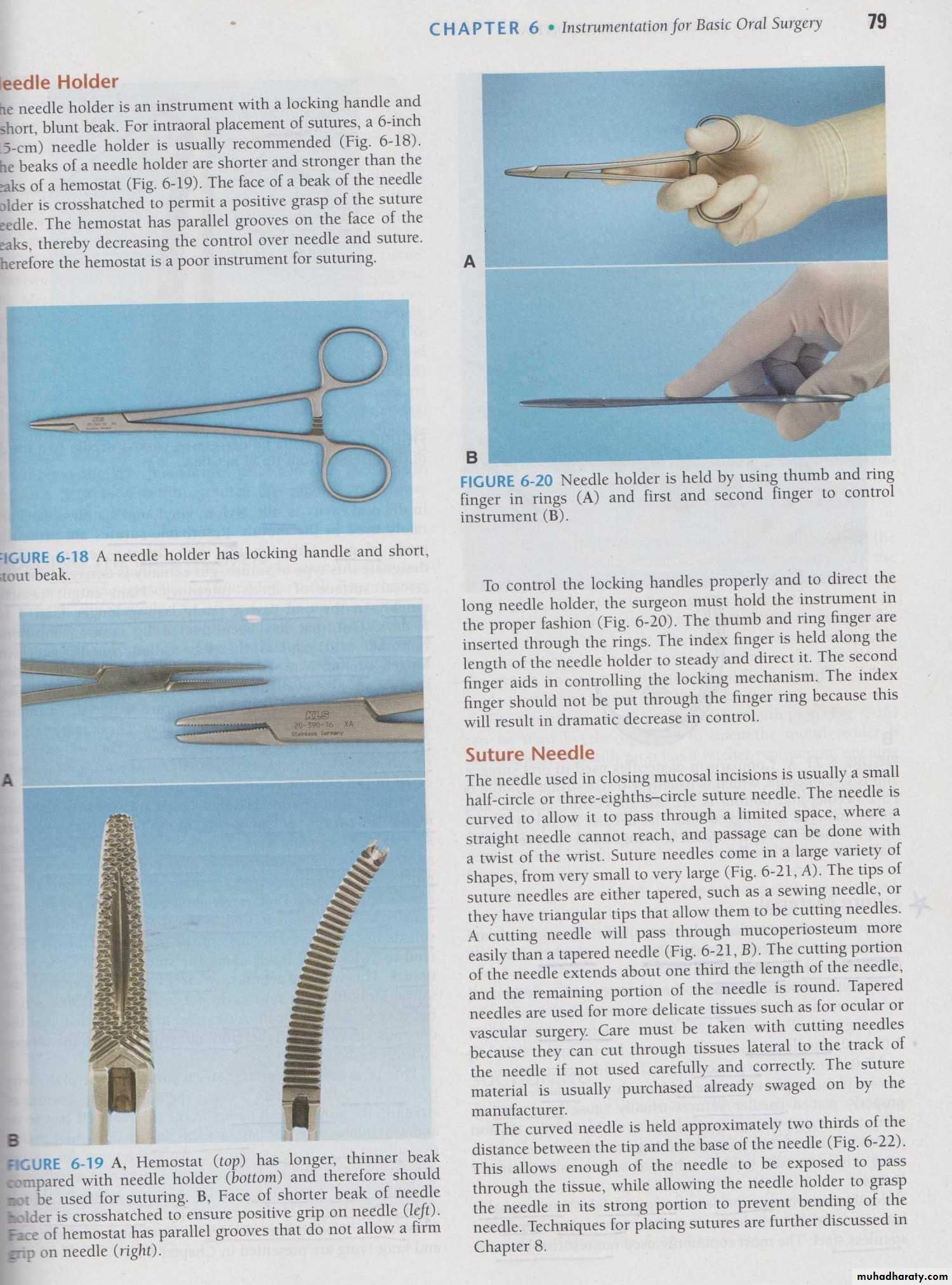

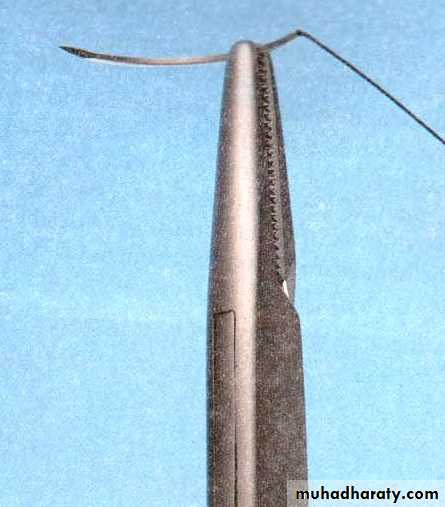

Flap returned to its original position & held by suturesI. Needle holder

Instrument with a locking handle, short, stout beak

Beak- shorter & stronger than hemostat

Face of the beak crosshatched :

positive grasp; unlike hemostat

COMPARISON

Hemostat: Beaks smaller than sinus forceps, longer than needle holder; transverse striations; ratchet

Needle holder: Criss-cross striations; ratchet

Sinus forceps: striations only near the tip; no ratchet

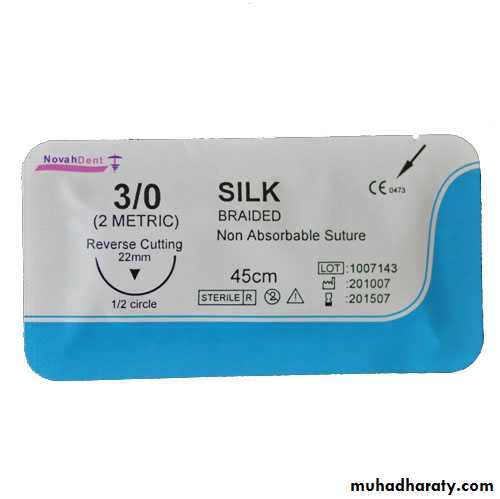

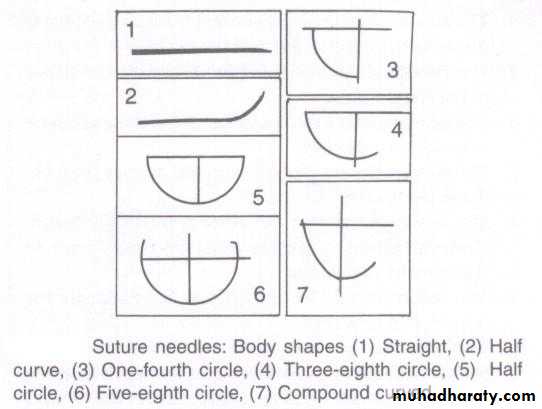

INSTRUMENTS FOR SUTURING MUCOSA

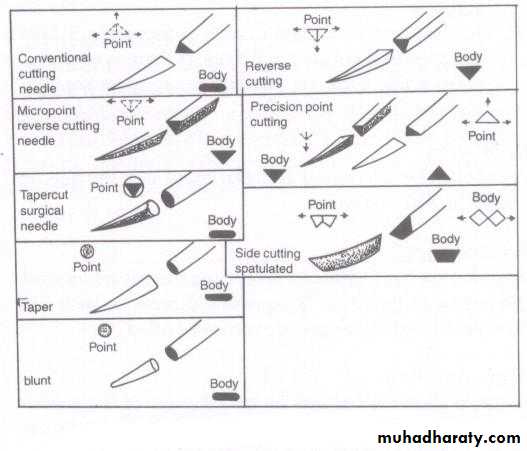

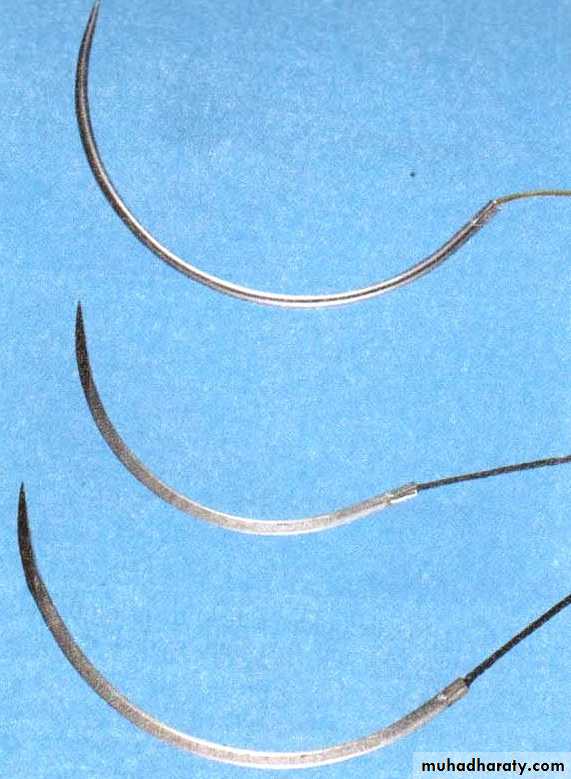

II. Suture needleMucosal closure: ½ circle or 3/8 circle

Curved: pass through a limited space; twisted wrist

Large variety of shapes

Very small – very large

Tips: (i) tapered- sewing needle

(ii) triangular – cutting needle

Cutting needle: pass through mucoperiosteum more easily than a tapered needle

1/3 – cutting; remaining- roundTapered :vascular, ocular

Suture material: usually swaged on

Held 2/3rd – between the tip & the base:- enough exposed to pass through the tissue

- grasp in the strong portion to prevent bending

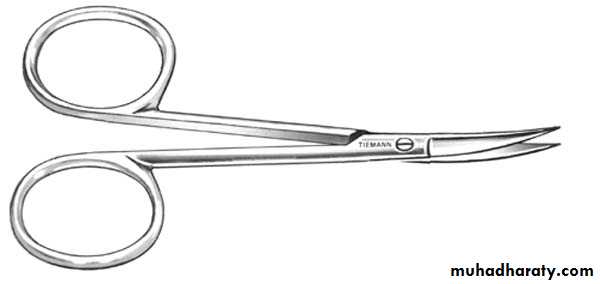

IV. Scissors

Short cutting edgesLong handles

Thumb & ring fingers

Held same as needle holder

Dean scissors

Slightly curved handles

Serrated blades

Mayo scissors

Straight-bladed Mayo scissors are designed for cutting body tissues near the surface of a wound. As straight-bladed Mayo scissors are also used for cutting sutures, they are also referred to as "suture scissors"Tissue scissors

Straight or curved bladesDon’t cut sutures: dull the edges- less effective & more traumatic

INSTRUMENTS FOR HOLDING THE MOUTH OPEN

Soft, rubberlike block- patient rests teethPatient opens to comfortably wide position- block inserted: holds in the position

Protects patient’s TMJ, while mandibular teeth

Mouth Gag

Forcefully open mouth: trismusBroad, serrated blades: rest on occlusal surface of molars: instrument opened : slow, gradual force

Keep mouth open: procedures under G/A

INSTRUMENTS FOR HOLDING TOWELS & DRAPES IN POSITION

Towel clipHolds together, drapes placed around a patient

Stabilizes suction tubes, micromotor etc.

Hold & retract tongue: unconscious patient

Locking handle + finger & thumb rings

Sharp/blunt action ends

Curved points- penetrate towels & drapes

Caution: not to pinch patient’s skin