Lecture 6

PROFESSOR DR. NUMAN NAFIE HAMEED

اﻻﺳﺘﺎذ

اﻟﺪﻛﺘﻮر

ﻧﻌﻤﺎن

ﻧﺎﻓﻊ

اﻟﺤﻤﺪاﻧﻲ

Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) 2010

MCQ?

In neonatal resuscitation program, the preterm neonates need special preparations

because they have all the following Except:

a. Preterm babies also have immature blood vessels in the brain that are

prone to hemorrhage

b. Have no susceptibility to infection

c. They are also more vulnerable to injury by positive-pressure ventilation.

d. increased risk of hypovolemic shock related to small blood volume

e. thin skin and a large surface area, which contribute to rapid heat loss

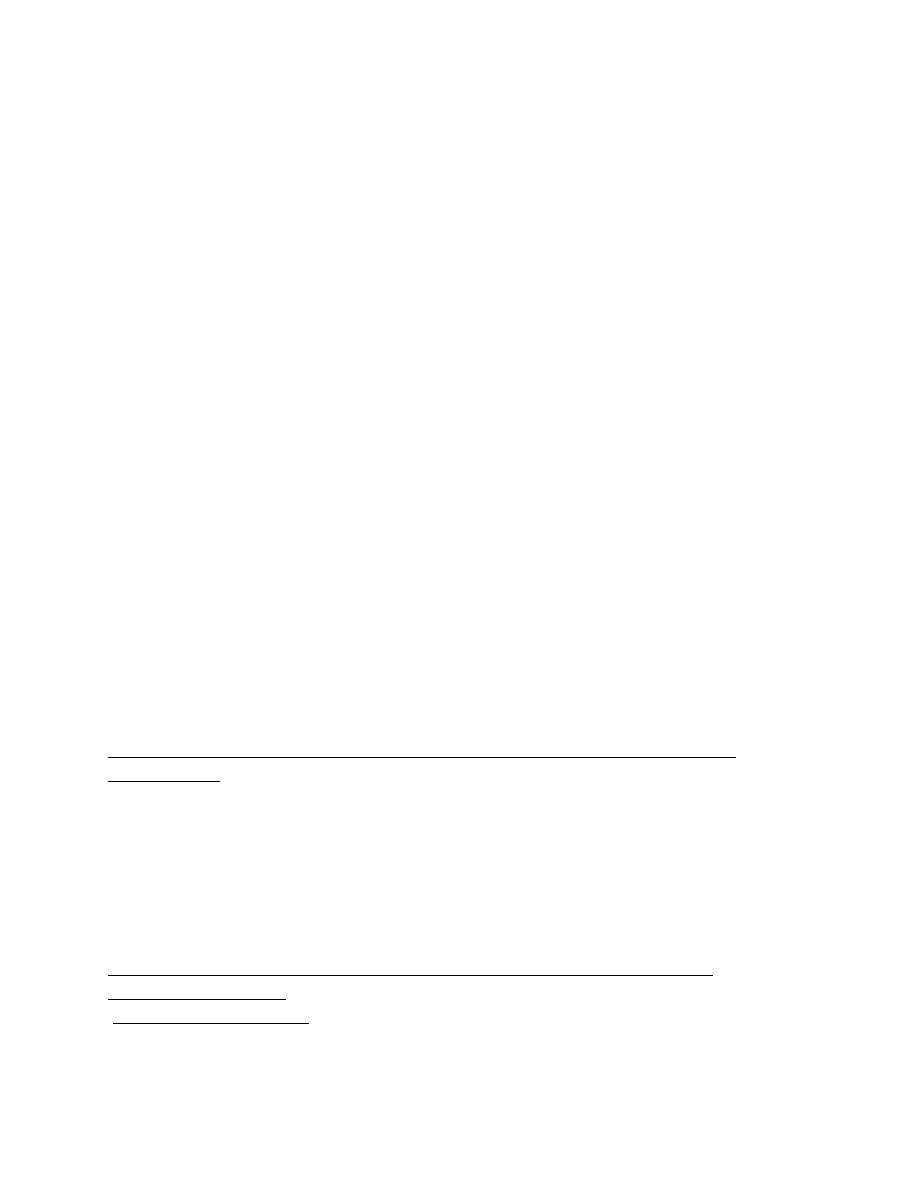

Approximately 10% of newborns require some assistance to begin breathing at

birth. Less than 1% requires extensive resuscitative measures. Although the vast

majority of newly born infants do not require intervention to make the transition

from intrauterine to extrauterine life, because of the large total number of births, a

sizable number will require some degree of resuscitation.

Those newly born infants who do not require resuscitation can generally be

identified by a rapid assessment of the following 3 characteristics:

● Term gestation?

● Crying or breathing?

● Good muscle tone?

If the answer to all 3 of these questions is “yes,” the baby does not need

resuscitation and should not be separated from the mother. The baby should be

dried, placed skin-to-skin with the mother, and covered with dry linen to maintain

temperature. Observation of breathing, activity, and color should be ongoing.

If the answer to any of these assessment questions is “no,” the infant should

receive one or more of the following 4 categories of action in sequence:

A. Initial steps in stabilization (provide warmth, clear airway if necessary, dry,

stimulate)

B. Ventilation

C. Chest compressions

D. Administration of epinephrine and/or volume expansion

1

Approximately 60 seconds (“the Golden Minute”) are allotted for completing the

initial steps, reevaluating, and beginning ventilation if required.

The decision to progress beyond the initial steps is determined by simultaneous

assessment of 2 vital characteristics: respirations (apnea, gasping, or labored or

unlabored breathing) and heart rate (whether greater than or less than 100 beats per

minute).

Assessment of heart rate should be done by intermittently auscultating the

precordial pulse. When a pulse is detectable, palpation of the umbilical pulse can

also provide a rapid estimate of the pulse.

A pulse oximeter can provide a continuous assessment of the pulse without

interruption of other resuscitation measures.

Once positive pressure ventilation or supplementary oxygen administration is

begun, assessment should consist of simultaneous evaluation of 3 vital

characteristics: heart rate, respirations, and the state of oxygenation, the latter

optimally determined by a pulse oximeter.

The most sensitive indicator of a successful response to each step is an increase in

heart rate.

Anticipation of Resuscitation Need

At every delivery there should be at least one person whose primary responsibility

is the newly born. This person must be capable of initiating resuscitation, including

administration of positive-pressure ventilation and chest compressions. Either that

person or someone else who is promptly available should have the skills required

to perform a complete resuscitation, including endotracheal intubation and

administration of medications. With careful consideration of risk factors, the

majority of newborns who will need resuscitation can be identified before birth.

If a preterm delivery (37 weeks of gestation) is expected, special preparations will

be required because:

1. Preterm babies have immature lungs that may be more difficult to ventilate and

are also more vulnerable to injury by positive-pressure ventilation

2. Preterm babies also have immature blood vessels in the brain that are prone to

hemorrhage

3. Thin skin and a large surface area, which contribute to rapid heat loss

4. increased susceptibility to infection

5. Increased risk of hypovolemic shock related to small blood volume.

Initial Steps

The initial steps of resuscitation are to provide warmth by placing the baby under a

radiant heat source, positioning the head in a “sniffing” position to open the

airway, clearing the airway if necessary with a bulb syringe or suction catheter,

drying the baby, and stimulating breathing.

2

Temperature Control

Very low-birth-weight (<1500 g) preterm babies are likely to become hypothermic

despite the use of traditional techniques for decreasing heat loss.

additional warming techniques are recommended (eg. prewarming the delivery

room to 26°C, covering the baby in plastic wrapping, placing the baby on an

exothermic mattress, and placing the baby under radiant heat .

The infant’s temperature must be monitored closely.

Other techniques for maintaining temperature during stabilization (eg, prewarming

the linen, drying and swaddling, placing the baby skin-to-skin with the mother and

covering both with a blanket) are recommended.

All resuscitation procedures, including endotracheal intubation, chest

compression, and insertion of intravenous lines, can be performed with these

temperature-controlling interventions in place.

Infants born to febrile mothers have been reported to have a higher incidence of

perinatal respiratory depression, neonatal seizures, and cerebral palsy and an

increased risk of mortality. Hyperthermia should be avoided.

The goal is to achieve normothermia and avoid iatrogenic hyperthermia.

Clearing the Airway When Amniotic Fluid Is Clear

There is evidence that suctioning of the nasopharynx can create bradycardia during

resuscitation and that suctioning of the trachea in intubated babies receiving

mechanical ventilation in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) can be associated

with deterioration of pulmonary compliance and oxygenation and reduction in

cerebral blood flow velocity when performed routinely (ie, in the absence of

obvious nasal or oral secretions).

However, there is also evidence that suctioning in the presence of secretions can

decrease respiratory resistance.

Therefore it is recommended that suctioning immediately following birth should

be reserved for babies who have obvious obstruction to spontaneous breathing or

who require positive-pressure ventilation (PPV).

When Meconium is Present Aspiration of meconium before delivery, during birth,

or during resuscitation can cause severe meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS).

In the absence of randomized, controlled trials, there is insufficient evidence to

recommend a change in the current practice of performing endotracheal suctioning

of nonvigorous babies with meconium-stained amniotic fluid .

However, if attempted intubation is prolonged and unsuccessful, bag-mask

ventilation should be considered, particularly if there is persistent bradycardia.

Assessment of Oxygen Need and Administration of Oxygen

Blood oxygen levels in uncompromised babies generally do not reach extrauterine

values until approximately 10 minutes following birth. Oxyhemoglobin saturation

3

may normally remain in the 70% to 80% range for several minutes following birth,

thus resulting in the appearance of cyanosis during that time.

Pulse Oximetry

It is recommended that oximetry be used when

1. Resuscitation can be anticipated,

2. When positive pressure is administered for more than a few breaths,

3. When cyanosis is persistent,

4. Or when supplementary oxygen is administered

Administration of Supplementary Oxygen

It is recommended that the goal in babies being resuscitated at birth, whether born

at term or preterm, should be an oxygen saturation value in the interquartile range

of preductal saturations measured in healthy term babies following vaginal birth at

sea level.

These targets may be achieved by initiating resuscitation with air or a blended

oxygen and titrating the oxygen concentration to achieve an SpO2 in the target

range.

If blended oxygen is not available, resuscitation should be initiated with air.

If the baby is bradycardic (HR <60 per minute) after 90 seconds of resuscitation

with a lower concentration of oxygen, oxygen concentration should be increased to

100% until recovery of a normal heart rate.

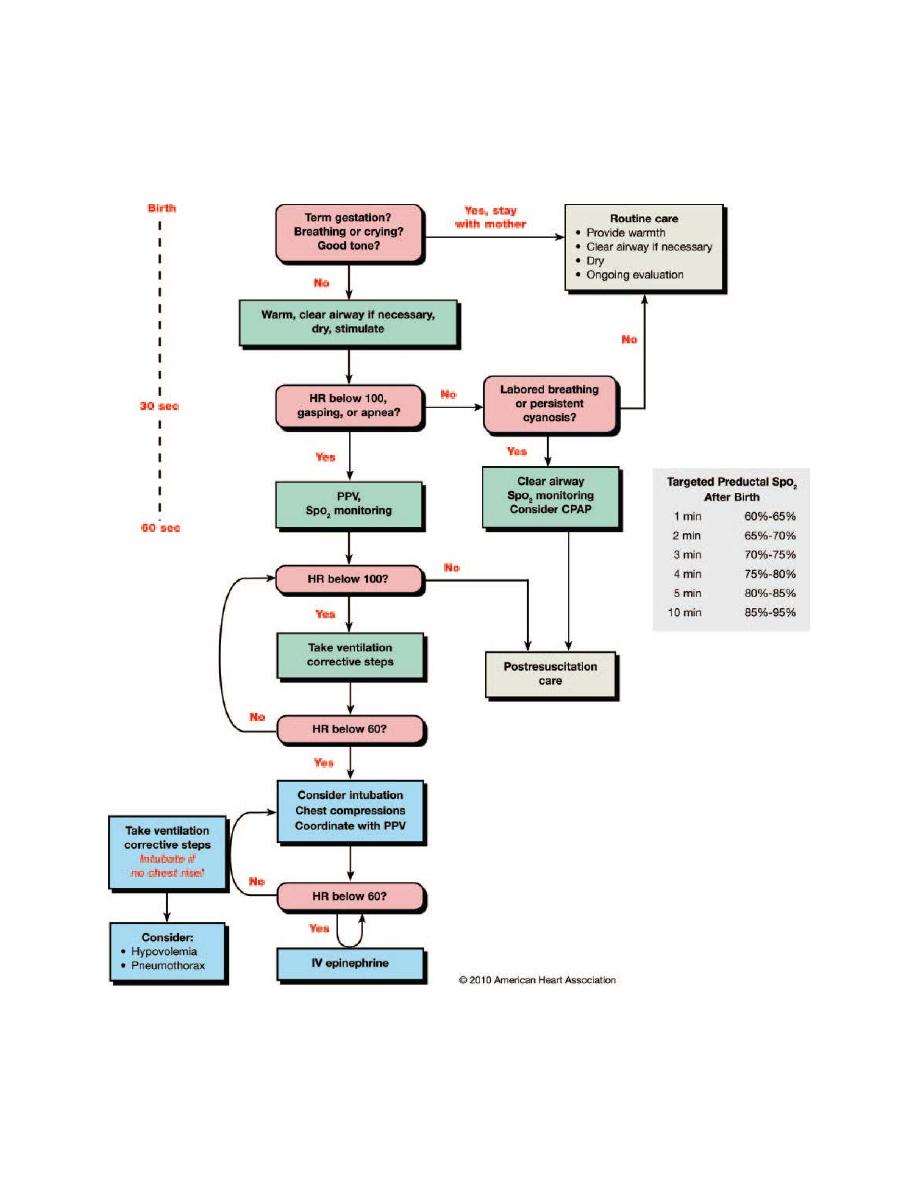

Positive-Pressure Ventilation (PPV)

If the infant remains apneic or gasping, or if the heart rate remains <100 per minute

after administering the initial steps, start PPV.

Initial Breaths and Assisted Ventilation

Assisted ventilation should be delivered at a rate of 40 to 60 breaths per minute to

promptly achieve or maintain a heart rate>100 per minute.

End-Expiratory Pressure

Many experts recommend administration of continuous positive airway pressure

(CPAP) to infants who are breathing spontaneously, but with difficulty, following

birth.

Starting infants on CPAP reduced the rates of intubation and mechanical

ventilation, surfactant use, and duration of ventilation, but increased the rate of

pneumothorax.

4

Spontaneously breathing preterm infants who have respiratory distress may be

supported with CPAP or with intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Nevertheless, PEEP is likely to be beneficial and should be used if suitable

equipment is available. PEEP can easily be given with a flow-inflating bag or T-

piece resuscitator.

Assisted-Ventilation Devices

Effective ventilation can be achieved with either a flow inflating or self-inflating

bag or with a T-piece mechanical device designed to regulate pressure.

Laryngeal Mask Airways

Laryngeal mask airways that fit over the laryngeal inlet have been shown to be

effective for ventilating newborns weighing more than 2000 g or delivered>34

weeks gestation.

There are limited data on the use of these devices in small preterm infants, ie,

<2000 g or <34 weeks. A laryngeal mask should be considered during resuscitation

if facemask ventilation is unsuccessful and tracheal intubation is unsuccessful or

not feasible.

The laryngeal mask airway (LMA) is used in various clinical

scenarios, including the followings:

a. In neonatal resuscitation of term and large > 34 weeks preterm babies

b. In the difficult airway, such as in the Robin sequence

c. As an aid to endotracheal intubation

d. As an aid in flexible endoscopy

e. In surgical cases in place of endotracheal intubation

Endotracheal Tube Placement

Endotracheal intubation may be indicated at several points during neonatal

resuscitation:

● Initial endotracheal suctioning of non-vigorous meconium stained newborns

● If bag-mask ventilation is ineffective or prolonged

● When chest compressions are performed

● For special resuscitation circumstances, such as congenital diaphragmatic hernia

or extremely low birth weight. The timing of endotracheal intubation may also

depend on the skill and experience of the available providers.

After endotracheal intubation and administration of intermittent positive pressure,

a prompt increase in heart rate is the best indicator that the tube is in the

tracheobronchial tree and providing effective ventilation.

Exhaled CO2 detection is effective for confirmation of endotracheal tube

placement in infants, including very low-birth-weight infants.

5

Other clinical indicators of correct endotracheal tube placement are condensation

in the endotracheal tube, chest movement, and presence of equal breath sounds

bilaterally.

Chest Compressions

Chest compressions are indicated for a heart rate that is<60 per minute despite

adequate ventilation with supplementary oxygen for 30 seconds.

Because ventilation is the most effective action in neonatal resuscitation and

because chest compressions are likely to compete with effective ventilation,

rescuers should ensure that assisted ventilation is being delivered optimally before

starting chest compressions.

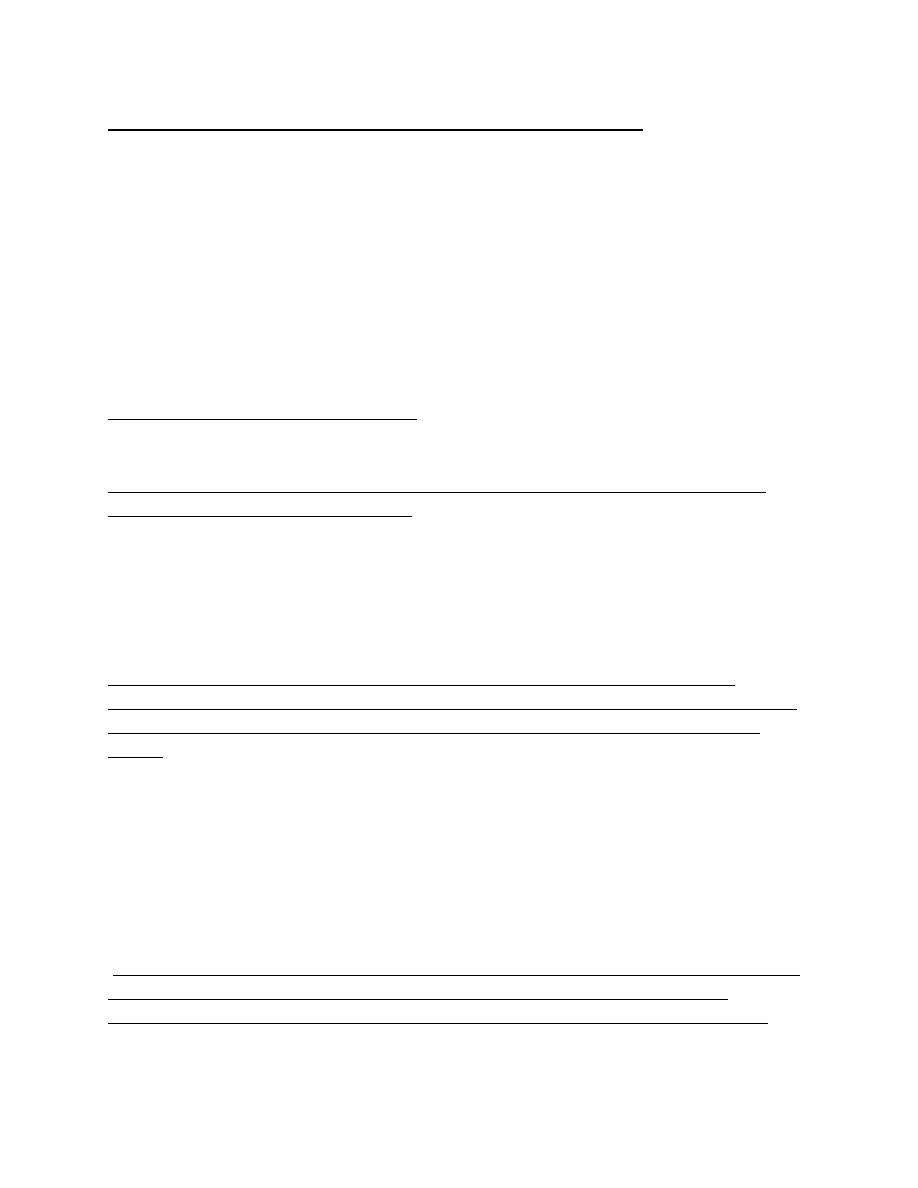

Compressions should be delivered on the lower third of the sternum to a depth of

approximately one third of the anterior-posterior diameter of the chest.

Two techniques have been described: compression with 2 thumbs with fingers

encircling the chest and supporting the back (the 2 thumb–encircling hands

technique) or compression with 2 fingers with a second hand supporting the back.

the 2 thumb–encircling hands technique is recommended for performing chest

compressions in newly born infants.

Compressions and ventilations should be coordinated to avoid simultaneous

delivery. The chest should be permitted to reexpand fully during relaxation, but the

rescuer’s thumbs should not leave the chest.

There should be a 3:1 ratio of compressions to ventilations with 90 compressions

and 30 breaths to achieve approximately 120 events per minute to maximize

ventilation at an achievable rate.

It is recommended that a 3:1 ratio be used for neonatal resuscitation where

compromise of ventilation is nearly always the primary cause, but rescuers should

consider using higher ratios (eg, 15:2) if the arrest is believed to be of cardiac

origin.

Respirations, heart rate, and oxygenation should be reassessed periodically, and

coordinated chest compressions and ventilations should continue until the

spontaneous heart rate is>60/ min.

Medications

Drugs are rarely indicated in resuscitation of the newly born infant.

Bradycardia in the newborn infant is usually the result of inadequate lung inflation

or profound hypoxemia, and establishing adequate ventilation is the most

important step toward correcting it.

However, if the heart rate remains <60/ min. despite adequate ventilation (usually

with endotracheal intubation) with 100% oxygen and chest compressions,

administration of epinephrine or volume expansion, or both, may be indicated.

6

Rarely, buffers, a narcotic antagonist, or vasopressors may be useful after

resuscitation, but these are not recommended in the delivery room.

Rate and Dose of Epinephrine Administration

Epinephrine is recommended to be administered intravenously. The IV route

should be used as soon as venous access is established.

The recommended IV dose is 0.01 to 0.03 mg/kg per dose. While access is being

obtained, administration of a higher dose (0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg) through the

endotracheal tube may be considered, but the safety and efficacy of this practice

have not been evaluated. The concentration of epinephrine for either route should

be 1:10,000 (0.1 mg/mL).

Volume Expansion

Volume expansion should be considered when blood loss is known or suspected

(pale skin, poor perfusion, weak pulse) and the baby’s heart rate has not responded

adequately to other resuscitative measures.

An isotonic crystalloid solution or blood is recommended for volume expansion in

the delivery room.

The recommended dose is 10 mL/kg, which may need to be repeated.

When resuscitating premature infants, care should be taken to avoid giving volume

expanders rapidly, because rapid infusions of large volumes have been associated

with intra-ventricular hemorrhage.

Post-resuscitation Care

Babies who require resuscitation are at risk for deterioration after their vital signs

have returned to normal. Once adequate ventilation and circulation have been

established, the infant should be maintained in, or transferred to an environment

where close monitoring and anticipatory care can be provided.

Naloxone

Administration of naloxone is not recommended as part of initial resuscitative

efforts in the delivery room for newborns with respiratory depression. Heart rate

and oxygenation should be restored by supporting ventilation.

Glucose

Newborns with lower blood glucose levels are at increased risk for brain injury and

adverse outcomes after a hypoxic ischemic insult, although no specific glucose

level associated with worse outcome has been identified.

Intravenous glucose infusion should be considered as soon as practical after

resuscitation, with the goal of avoiding hypoglycemia.

Induced Therapeutic Hypothermia

It is recommended that infants born at >36 weeks gestation with evolving moderate

to severe hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy should be offered therapeutic

hypothermia.

7

The treatment should be implemented according to the studied protocols, which

currently include commencement within 6 hours following birth, continuation for

72 hours, and slow rewarming over at least 4 hours.

8

9

Equipment Needed for Intubation

• Laryngoscope with premature (Miller no. 0) and infant blades (Miller no. 1); Miller no.

00 optional for extremely premature infant

• Batteries and extra bulbs

• Endotracheal tubes, sizes 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, and 4.0 mm ID

• Stylet

• Suction apparatus (wall)

• Suction catheters: 5.0, 6.0, 8.0, and 10.0 French

• Meconium aspirator

• Oral airway

• Stethoscope

• Non–self-inflating bag (0.5 L), manometer, and tubing; self-inflating bag with reservoir,

manometer optional for self-inflating bag

• Newborn and premature mask

• Source of compressed air/O

2

with capability for blending

• Humidification and warming apparatus for air/O

2

•

Tape

• Scissors

• Magill neonatal forceps

• Elastoplast (elastic bandages)

• Cardiorespiratory monitor

• Carbon dioxide monitor or detector

• Pulse oximeter (Spo

2

)

Summary of changes since 2010 guidelines

The following are the main changes that have been made to the guidelines for

resuscitation at birth in 2015:

• Support of transition: Recognising the unique situation of the baby at birth, who

rarely requires

‘resuscitation’ but sometimes needs medical help during the process of

postnatal transition.

The term

‘support of transition’ has been introduced to better distinguish between

interventions that are needed to restore vital organ functions (resuscitation) or to

support transition.

• Cord clamping: For uncompromised babies, a delay in cord clamping of at least 1 min

from the complete delivery of the infant, is now recommended for term and preterm

babies. As yet there is insufficient evidence to recommend an appropriate time for

clamping the cord in babies who require resuscitation at birth.

• Temperature: The temperature of newly born non-asphyxiated infants should be

maintained between 36.5

◦C and 37.5 ◦C after birth. The importance of achieving this

has been highlighted and reinforced because of the strong association with mortality

and morbidity. The admission temperature should be recorded as a predictor of

outcomes as well as a quality indicator.

• Maintenance of temperature: At <32 weeks gestation, a combination of interventions

may be required to maintain the temperature between 36.5

◦C and 37.5 ◦C after

delivery through admission and stabilisation. These may include warmed humidified

respiratory gases, increased room temperature plus plastic wrapping of body and head,

plus thermal mattress or a thermal mattress alone, all of which have been effective in

reducing hypothermia.

• Optimal assessment of heart rate: It is suggested in babies requiring resuscitation

that the ECG can be used to provide a rapid and accurate estimation of heart rate.

• Meconium: Tracheal intubation should not be routine in the presence of meconium

and should only be performed for suspected tracheal obstruction. The emphasis should

be on initiating ventilation within the first minute of life in non-breathing or

ineffectively breathing infants and this should not be delayed.

• Air/Oxygen: Ventilatory support of term infants should start with air. For preterm

infants, either air or a low concentration of oxygen (up to 30%) should be used initially.

If, despite effective ventilation, oxygenation (ideally guided by oximetry) remains

unacceptable, use of a higher concentration of oxygen should be considered.

• Continuous Positive Airways Pressure (CPAP): Initial respiratory support of

spontaneously breathing preterm infants with respiratory distress may be provided by

CPAP rather than intubation

11