0

Mustafa Hatim Kadhim

Baghdad University

Al-kindy college of medicine

Third Stage

2013 - 2014

1

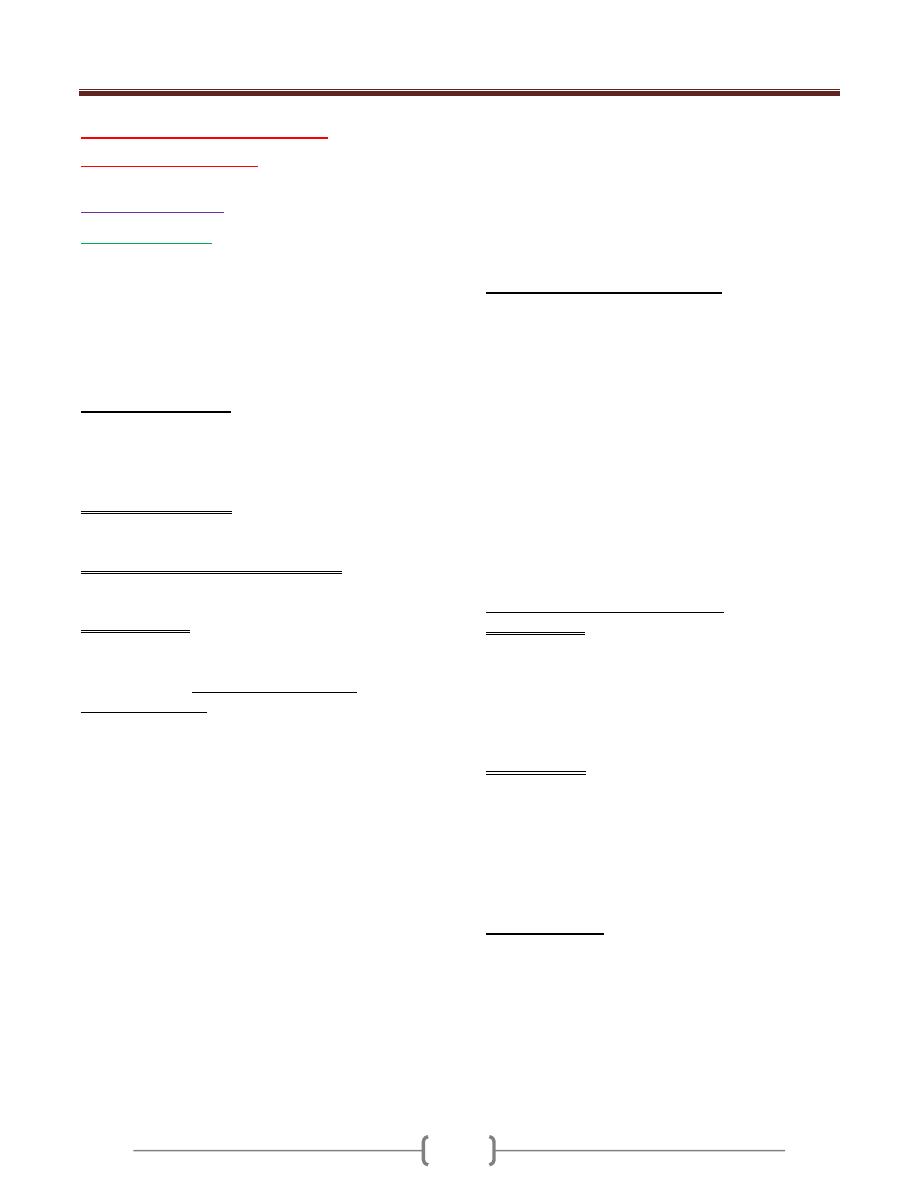

List of contents

Lecture

number

Lecture name

Doctor name

Page number

Unit 1: Immunology (3 – 57)

1

Introduction

دكتورة

بتول

4 - 6

2

Antibodies & Cytokines

7 - 12

3

Cells of the immune system, receptors,

mechanisms of action

13 - 16

4

Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) &

Complement system

17 - 20

5

Hypersensitivity

21 - 25

6

Tolerance & Autoimmunity

26 - 28

7

Transplantation

29 - 31

8+9+10

Immune response to infectious diseases

دكتورة

ايمان

32 - 43

11+12+13

Immunodeficiency

44 - 50

14

Tumor Immunology

51 - 53

15

Vaccines

54 - 57

Unit 2: Bacteriology (58 – 135)

General Bacteriology (59 – 76)

1

General Microbiology

دكتور

نجاح

60 - 62

2

The Morphology & Fine structure of bacteria

63 - 65

3

The Physiology of Metabolism and Growth in

Bacteria

66 - 69

4

The Molecular Basis of Bacterial Genetics

70 - 72

5

The Principles of antibacterial therapy

73 - 76

Gram Positive Bacteria (77 – 103)

1

Staphylococcus

دكتور

نجاح

78 - 79

2

Streptococcus and Enterococcus

80 - 84

3

Pathogenic Neisseria, Moraxella and Acinetobacter

85 - 87

4

Aerobic Spore-Former Bacteria (Bacillus)

88 - 90

5

Anaerobic Spore-Former Bacteria (Pathogenic

Clostridia)

91 - 94

6

Corynebacterium & Diphtheroid

95 - 97

7

Mycobacteria

98 - 101

2

8

Nocardia & Listeria monocytogenes

102 - 103

Gram Negative Bacteria (104 – 135)

1+2+3

Enteric gramnegetive rods (enterobacteriaceae)

Enteric bacteria or coliform

دكتورة

جميلة

105 - 109

4

Pseudomonads, Acinetobacter & Uncommon gram

negative bacteria

110 - 111

5

Vibrios (vibrio spp.) & associated bacteria

112 - 113

6

Campylobacters & Helicobacter

114 - 115

7

Haemophilus

116 - 117

8

Bordetellae

118 - 119

9

Legionellae, Bartonella & unusual bacterial

pathogens

120 - 122

10+11

zoonotic gram negative rods

123 - 125

12+13

Spirochetes

126 - 130

14

Mycoplasma, Chlamydia & Rickettsiae

131 - 133

15

Normal microbial flora

134 - 135

Unit 3 – Mycology (136 – 150)

1

Introduction to mycology

دكتورة

اروى

137 - 139

2+3+4+5

Fungal diseases in humans (mycoses)

140 - 148

6

Antifungal Chemotherapy

149 - 150

Unit – Virology (151 – 192)

1+2+3

Introduction

دكتور

حيدر

152 - 156

4

Antiviral Drugs

157 - 159

5+6+ Half 7

RNA Enveloped viruses

160 - 167

Half 7+8

RNA non enveloped viruses

168 - 170

9+10

Retroviruses

171 - 175

11+12

DNA enveloped viruses

176 - 180

13

DNA Non-enveloped Virus

181 - 182

14+15+16

Viral Hepatitis

183 - 188

17

Human cancer viruses

189 - 190

18

Slow Viruses & Prions

191

19

Arbovirus

192

3

Unit 1 - Immunology

4

Lecture 1 - Introduction

Immunity: is resistance to disease

Immune system: collection of cells, tissues, molecules

that mediate response.

Immune response: Coordinated reaction of cells and

molecules to infectious disease.

Immunology: Is the science that study immune system

and its response to pathogens

Function of the immune system:

Prevent infection

Eradicate established infection

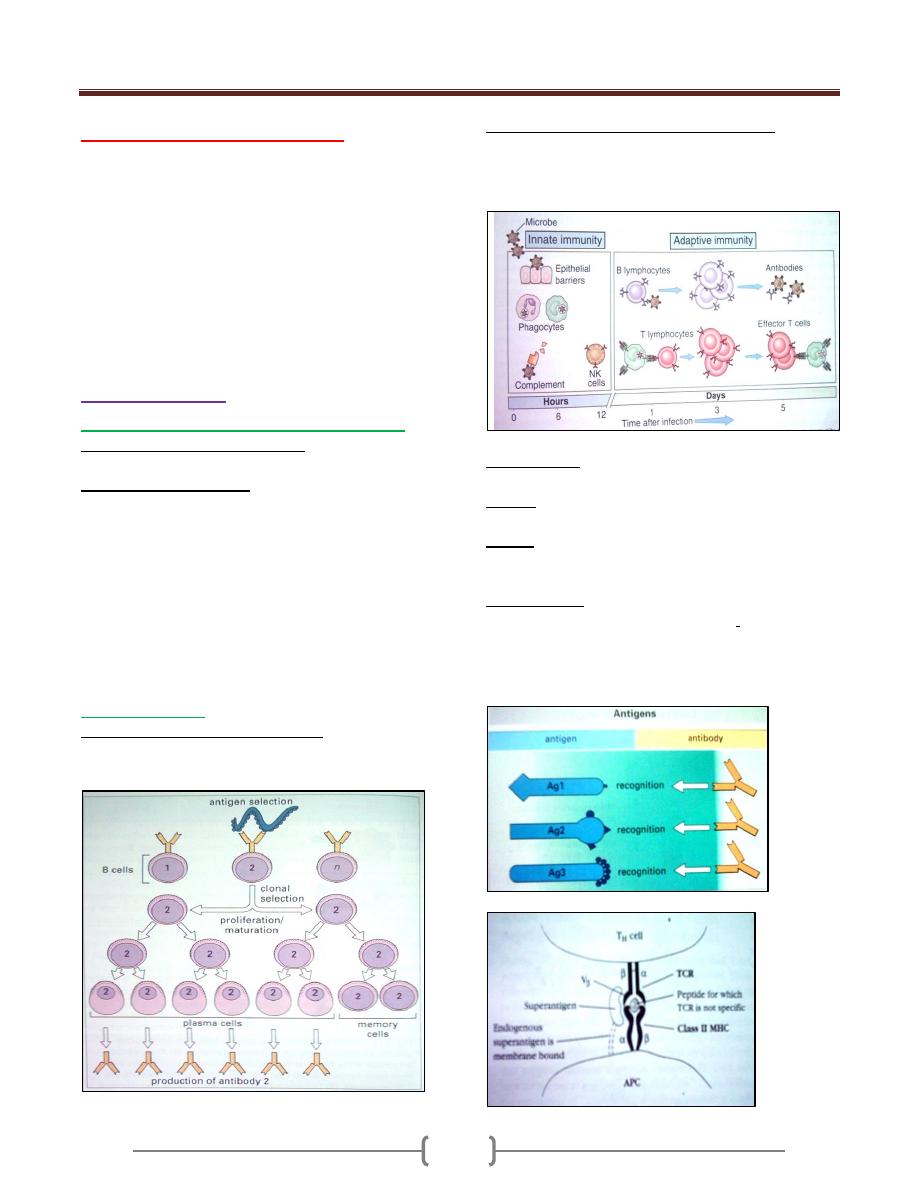

Types of immunity

1) Innate immunity:Exterior defense mechanism

Characteristics of innate immunity

1) Preexist 2) Not specific 3) No memory

Types of innate immunity:

1. Anatomic barrier( skin, mucous membrane)

2. Physiologic barriers( tempretire, PH, oxygen)

3. Chemical barriers( Lysozyme, Defensin, Interferon,

complement)

4. Cellular barrier: Neutrophils, Macrophage, Natural

killer cells and dendritic cells.

5. Toll-like receptors:It presents on phagocytic cells that

recognize broad molecules on pathogens enhancing

phagocytosis. It is called pattern recognition receptors

or pathogen associated molecular patterns.

2) Adaptive immunity

Characteristics of Adaptive immunity

1) Specificity 2) Diversity 3) Memory

4) Self non self-recognition 5) Clonal expansion

Central cell in the adaptive immune response

Lymphocytes

1- T lymphocytes-----cell mediated immunity

2- B lymphocytes-------humoral immunity

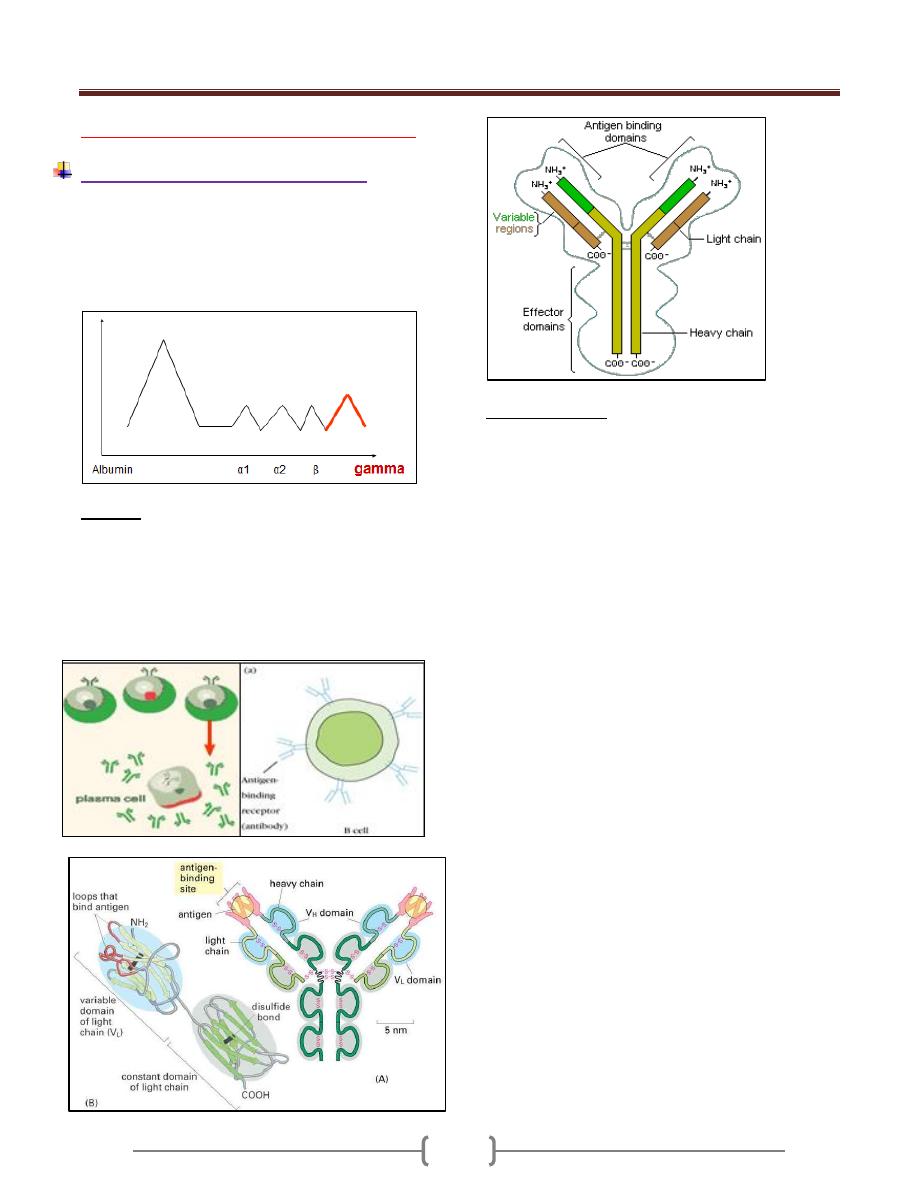

Antigens (Ag): any molecule that can be specifically

recognized by the adaptive immune system

Epitope: is a restricted part of Ag (short sequence of

sugars, a.a., that bind with antibodies (Abs).

Hapten: a small molecule had a low molecular weight

that cannot initiate an immune response unless its coupled

with a large carrier molecule

Super antigen: certain bacterial toxin (Staphylococcal

enterotoxins can bind to multiple T cells by binding to

T-cell receptor variable beta regions to alpha chain of

class II major histocompatibility complex on antigen

presenting cells.

Unit 1 - Immunology

5

Factors determining antigenicity

1. Degree of foreignness

2. Molecular size:100000 dalton

3. Chemical compositions: proteins-polysaccharide-lipid-

nucleic acids

4. Susceptibility to antigen processing

5. Genotype

6. Dose of immunogens

7. Route of adminstration

8. Adjuvants:substanc mix with Ag to enhance

immunogenicity(Alum-Aluminum potassium sulfate)

Generation of mature lymph. first occurs in the embryo in

-yolk sac

-fetal liver

-fetal bone marrow and continues throughout life

in birds /lymphoid organs called Bursa of fibricius

(primary site of B-cell maturation)

In humans –BM and other lymphoid tissue serve as Bursa

equivalent

Lymphocytes:

B lymphocytes (B cells)

T lymphocytes (T cells)

Important for the adaptive immune response.

B cells:

Surface receptor = Immunoglobulin (Ig).

Humoral Immunity.

Unit 1 - Immunology

6

Thymus

Its flat, bilobed organ situated above the heart. Each lobe

is surrounded by a capsule divide into lobule and

separated from each other by a trabeculae.Each lobule is

organized into cortex and medulla.

Hormones (thymosin, thymulin )and (enzymes like

adenosine deaminase)

Progenitor T cells in hematopoiesis in bone marrow then

ente thymus and acquire differentiation markers during

development calld CD markers (CD) markers.

Immature double negative (CD3+ CD4- CD8-) then

immature double positive thymocytes (CD3+ CD4+

CD8+) then mature single positive single negative

thymocytes (CD3+ CD4+ CD8-)(CD3+ CD4 –CD8+)

Thymic education and selection

The property of mature T cells is recognized only

foreign Ag (non self)+self MHC molecule. This can be

achived by selection process

Negative selection.

Positive selection.

The two processes called lymphocytes teachings.

Negative selection

Any lymph. Acquire receptors with high affinity for self

Ags will be die by a programmed cell death (apoptosis).

This occurs in the medulla by macrophages and dendretic

cells. (95-99%)

Positive selection

Any lymph. Acquire receptors recognize foreign Ags+

self MHC molecule will allow to mature and expand and

survive (1-5%). This occurs in the cortex of the thymus by

epithelial cells.

Lymphocytes homing

Lymphocytes leave thymus to sec. lymphoid organs (LN)

and to sites of inflammations through high endothelial

venules (HEV) by binding to specific receptors on lym.

and cell adhesion molecules on HEV after that lym.

homing to different tissues (GALT, MALT, skin dermal

endothelial venules ) by a cascade of interactions between

adhesions molecules on lym. And other cells.

Lymph nodes

Bean shaped, encapsulated ,containing a reticular network

packed with lymp., macrophages and dendretic cells .

Consist of 3 layers: Cortex, Paracortex & Medulla.

Unit 1 - Immunology

7

Lecture 2 – Antibodies & Cytokines

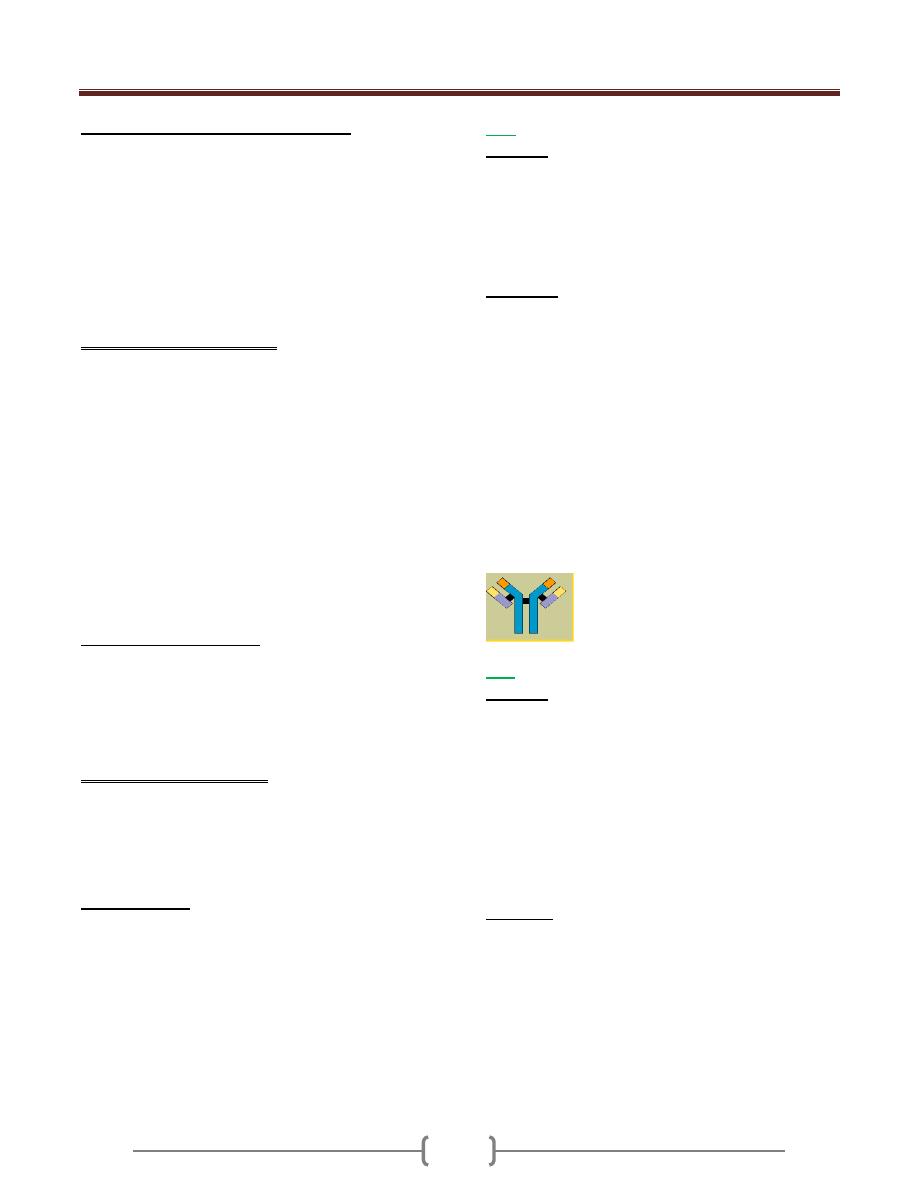

Immunoglobulin Antibody (Ab)

1) Blood from an individual and put it in a plain tube

without anticoagulant and left it for half an hour.

2) Blood will coagulate and you will get serum.

Protein electrophoresis: Gamma globulin fraction of

protein has antibody activity.

Antibody

Is a specific glycoprotein developed for a specific

antigen.

Synthesized by:

B-Cells armed on its surface and act as a surface

molecule bind an antigen

plasma cell that secrets free specific antibodies

Structure of Ab

Each antibody is made up of two identical heavy

polypeptide chains and two identical light polypeptide

chains, shaped to form a Y Linked covalently bind by a

disulfide bounds

Heavy chain (H) has a molecular weight twice that of

light chain (L), so called heavy and light.

Each polypeptide chain is not linear but folded to form

domes or loops by intrachain disulfide bonds (-s-s) and

called domains.

Light chain had one VL and CL domain

Heavy chain had one VH an CH 1,2,3,

Hinge region: area of heavy chain between CH1 and CH2

domains where the disulfide bond is present. It is a

flexible area permits the movement of Ab binding

fragment (Fab) from 30-180

o

.

Each chain has two regions:

1) The Variable Region: makes up the tips of the Y's arms,

represent the amino terminal of polypeptide chain, varies

greatly in shape from one antibody to another.

This variation is due to change in aa sequence for this

reason called the variable region. it has unique shape

that "match" antigen to antibody., such as a lock

matches a key

2) The Constant Region: The stem of the Y activates the

complement system and encourages phagocytosis

Its amino acid content and sequence is relatively

constant and identical in all antibodies of the same

class and it's called the constant region. It represents

the carboxy terminal of polypeptide chain. This region

of the antibody molecule is called the Fc

region because it can be crystallized.

Unit 1 - Immunology

8

In this variable region (heavy and light) , there is a three

area called a hypervariable region in that area the aa

sequence is highly variable and called the

Complemantarity Determining Region (CDR). This binds

epitope of Ag.

The regions between the complementarity determining

regions are called the framework regions

Paratope: It is a small region (of 15–22 amino acids) of

the antibody's Fv region and contains parts of the

antibody's heavy and light chains

Affinity: Strength of interaction between single epitope

and single paratope.

Functions of Igs

1) Activation of complement

2) Opsonization

3) Ab dependent cell mediated cytotoxicity

4) (ADCC)

5) 4- Neutralization of toxins

6) 5- Agglutination of RBC

7) 6- Blocking the reaction

Unit 1 - Immunology

9

Immunoglobulin Classes (ISOTYPES)

Immunoglobulin classes

The immunoglobulins can be divided into five different

classes, based on differences in the amino acid

sequences in the constant region of the heavy chains.

1. IgG - Gamma heavy chains

2. IgM - Mu heavy chains

3. IgA - Alpha heavy chains

4. IgD - Delta heavy chains

5. IgE - Epsilon heavy chains

Immunoglobulin Subclasses

The classes of immunoglobulins can be divided into

subclasses based on small differences in the amino acid

sequences in the constant region of the heavy chains. All

immunoglobulins within a subclass will have very similar

heavy chain constant region amino acid sequences.

1. IgG Subclasses

a) IgG1 - Gamma 1 heavy chains

b) IgG2 - Gamma 2 heavy chains

c) IgG3 - Gamma 3 heavy chains

d) IgG4 - Gamma 4 heavy chains

2. IgA Subclasses

a) IgA1 - Alpha 1 heavy chains

b) IgA2 - Alpha 2 heavy chains

Immunoglobulin Types

Immunoglobulins can also be classified by the type of light

chain that they have. This based on differences in the amino

acid sequence in the constant region of the light chain

1-Kappa light chains

2- Lambda light chains

Immunoglobulin Subtypes

The light chains can also be divided into subtypes based

on differences in the amino acid sequences in the constant

region of the light chain.

1- Lambda 1 2- Lambda 2 3- Lambda 3 4- Lambda 4

Nomenclature

Immunoglobulins are named based on the class, or

subclass of the heavy chain & type or subtype of light

chain.

IgG = Immunoglobulin Gamma .

IgM - Immunoglobulin Mu

IgA - Immunoglobulin Alpha

IgD - Immunoglobulin Delta

IgE - Immunoglobulin Epsilon

IgG

Structure

The structures of the IgG are made up of two identical

heavy chains and two identical light chains.

All IgG's are monomer. MW=150 000 d.

called so because of its gamma heavy chain

The subclasses (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4) differ in the

number of disulfide bonds and length of the hinge region.

Properties:

a) IgG is the major Ig in serum - 75% of serum Ig

b) IgG is the major Ig in extra vascular spaces

c) Placental transfer - IgG is the only class of Ig that crosses

the placenta. IgG2 does not cross well.

d) Fixes complement - Not all subclasses fix equally well;

IgG4 does not fix complement

e) Binding to cells - Macrophages, PMN IgG2 and IgG4 do

not bind to Fc receptors. A consequence of binding to the

Fc receptors on PMNs, monocytes and macrophages. The

antibody has prepared the antigen for eating by the

phagocytic cells. The term opsonin is used to describe

substances that enhance phagocytosis.

f) main Ig in the secondary immune response

IgA

Structure

1- Serum IgA is a monomer

2- IgA found in secretions is a dimer

When IgA exits as a dimer, a J chain is associated with it &

another protein associated with it called the secretory piece

J chain: small glycoprotein that are covalently linked to

the carboxy terminal portions of heavy chains.

Secretary component: is a polypeptide chain synthesized

by exocrine epithelial cells that enable IgA to pass

through mucosal tissues into secretions and protect IgA

from protease enzymes.

Properties

a) IgA is the 2nd most common serum Ig.

b) IgA is the major class of Ig in secretions - tears, saliva,

colostrum, mucus called secretory IgA

c) IgA activates the alternative pathway of complement

d) IgA can bind to some cells - PMN's and some

lymphocytes.

e) E) MW=150 000- 600 000 d

f) F) constitutes 10-15 % of serum Ig

Unit 1 - Immunology

10

g) It is called so because of its alpha heavy chain

components and of two subclasses:

1- Alpha 1-----IgA1

2- alpha 2 -----IgA2

IgM

Structure

1) IgM normally exists as a pentamer but it can also exist as

a monomer on B cell. In the pentameric form all heavy

chains are identical and all light chains are identical.

Thus, the valence is theoretically 10 times

2) IgM did not has a hing region and replaced by an extra

domain on the mu chain (CH4) , so it has 4 constant

heavy domains

3) It has another protein covalently bound via a S-S bond

called the J chain. This chain functions in polymerization

of the molecule into a pentamer.

Properties:

a. IgM is the third most common serum Ig. Constitute 5-

10% of total serum Ig .

MW=900 000 dalton

b. IgM is the first Ig to be made by the fetus and the first Ig

to be made by a virgin B cells as an Ag receptor.

c. As a consequence of its pentameric structure, IgM is a

good complement fixing

d. As a consequence of its structure, IgM is also a good

hemagglutinating Ig

e. IgM binds to some cells via Fc receptors.

f. Called so because of Mu heavy chain

IgE

Structure

IgE exists as a monomer and has an extra domain in the

constant region had four CH domains.

Properties

a) IgE is the least common serum Ig since it binds very

tightly to Fc receptors on basophils and mast cells

b) Involved in allergic reactions - Binding of the allergen to

the IgE on the cells results in the release of various

pharmacological mediators that result in allergic

symptoms.

It is called homocytotropic (bind cell) & called reagenic Ab

c) IgE also plays a role in parasitic helminth diseases. Since

serum IgE levels rise in parasitic diseases, measuring IgE

levels is helpful in diagnosing parasitic infections.

Eosinophils have Fc receptors for IgE and binding of

eosinophils to IgE-coated helminths results in killing of

the parasite.

d) IgE does not fix complement.

e) MW=190 000 d

f) constitutes about 0.002% of total serum Ig

g) called IgE because of its epsilon ε heavy chain

components

IgD

Structure

IgD exists only as a monomer.

Properties

a) IgD is found in low levels in serum; constitutes about

0.2% of total serum Ig

its role in serum uncertain.

MW=150 000 D

b) IgD is primarily found on B cell surfaces where it

functions as a receptor for antigen.

c) IgD does not bind complement

d) D) called IgD because of its delta δ heavy chain

components.

Variation of Igs

1) Isotypes: All classes and subclasses of Ig that are present

in normal individuals (IgG,IgM,IgA,IgE,IgD)

2) Allotype: That there is a single aa ifference in the

peptide chain in CH and CL chain

3) Idiotype: represents the antigen binding specificities of

Igs. The unique aa sequence of VH and VL can function

as antigenic determinants.

Unit 1 - Immunology

11

Immune response

primary humoral immune response. The first contact of

an exogenous Ag with an individual leads to generation a

Characteristics:

1- longer lag phase: during this period , the naive B cells

undergo clonal selection, clonal expansion and

differentiation into memory and plasma cells

2- Log phase (logarithmic): increase in IgM

concentration.

Secondary immune response

Second contact with same exogenous antigen, generates

secondary humoral immune response.

Characterization:

1-shorter lag phase

2-Rapid reaches a greater magnitude of IgG and last for

longer time. This is because of memory B-cells specific

for this Ag is existed. The processes of affinity maturation

and class switching are responsible for higher affinity to

Ag and different isotype

Vaccination (immunization)

Used to provoke a positive immune response by an

individual to various pathogenic microorganisms to

confer protection.

Polyclonal antibody

Most Ags possess multiple epitopes and each one of them

induce different B cells to proliferate into many clones of

cells that recognize different epitopes, these B cells secret

Abs, resulting into a mixture of Abs called polyclonal Abs

Monoclonal antibody

A clone of single B-cells that recognize a single epitope

that secret Abs spesific to a single epitope so it’s called

monoclonal Abs. It’s used for diagnostic and theraputic

purposes.

Unit 1 - Immunology

12

Cytokines

Are regulatory proteins or glycoproteins of low molecular

weight secreted by white blood cells and other cells in

response to a number of stimuli.

Function as intercellular messenger that evoke particular

biological activity after binding to a specific receptor.

Nomenclature

Lymphokines: cytokines secreted by lymphocytes.

Monokines: cytokines secreted by monocytes and

macrophages.

Interlukines

: cytokines are secreted by some leukocytes

and act upon other leukocytes.

IL-1

o Secreted by macrophages

o Act on lymphocytes

o Induce lymphocytes maturation , activation and clonal

expansion

o Acts on hypothalamus inducing fever

IL-2

o Secreted from Th1

o Acts on Ag specific T-cell supporting its growth

o Acts on NK cell increasing activity

o Acts on Tc cell increasing cytotoxicity

o Leads to development cell mediated immunity

o Suppress cytokines secreted from Th2 cells.

IL-3

o Secreted from Th2

o Supports growth and differentiation of hematopoietic cells

IL4 and IL-5

o Secreted from TH2

o Its up-regulate classII MHC expression

o Stimulate growth of mast cell

o Stimulate proliferation of activated B-cell

o Stimulate Abs secretions from plasma cell

o Stimulates humoral immune response

o Down regulates Th1

o IL-4 promotes class switch to IgE

o IL-5 promotes Eosinophil activation and generation

IL-6

o Secreted by macrophages and endothelial cells.

o Effect liver induces acute phase protein synthesis and

proliferation and antibody secretion of B-cells.

IL-10

o Secreted from Th2

o Antagonizes generation of Th1 subsets and cytokines

production by TH cell

o Mediate regulation of the immune system

Interferon (IFN)

o IFN α:secreted from leukocytes and inhibit viral

replication

o IFN β:secreted from fibroblasts and inhibit viral

replication

o IFN γ:secreted from Th1, Tc, NK cell and inhibit viral

replication,

Enhance activity of macrophages,

Increase MHC class-II expression,

Inhibits Th2 proliferation

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)

o TNF :secreted from macrophages and act on tumor cells

o Had direct cytotoxic effect on tumor cells and tumor

undergoes visible hemorrhagic necrosis and regression by

inhibition angiogenesis, thereby decreasing the flow of

blood that is necessary for progressive tumor growth.

o Causes extensive loss weight (cachexia) by suppression

lipogenetic metabolism.

Unit 1: Immunology

13

Lecture 3 - cells of the immune system,

receptors, mechanisms of action

Unit 1: Immunology

14

Unit 1: Immunology

15

Unit 1: Immunology

16

Unit 1: Immunology

17

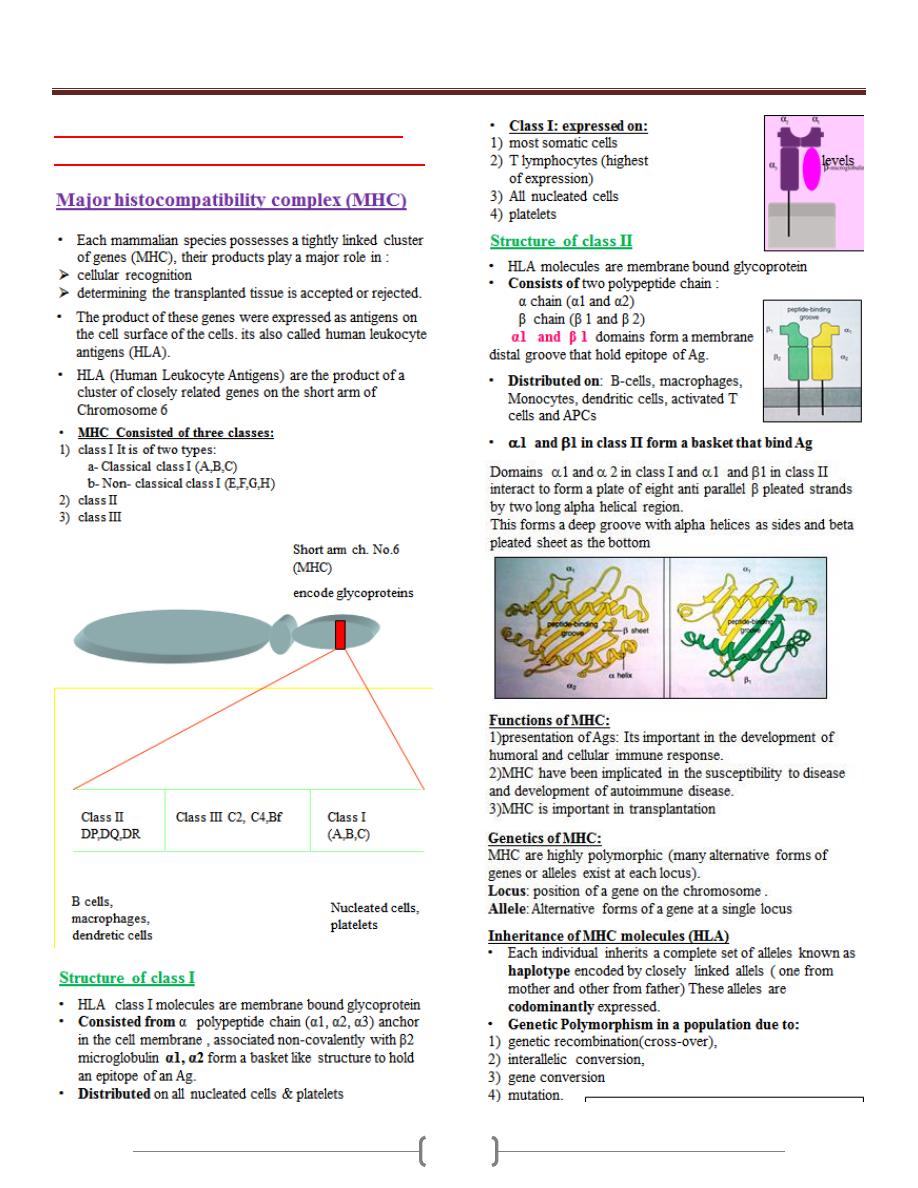

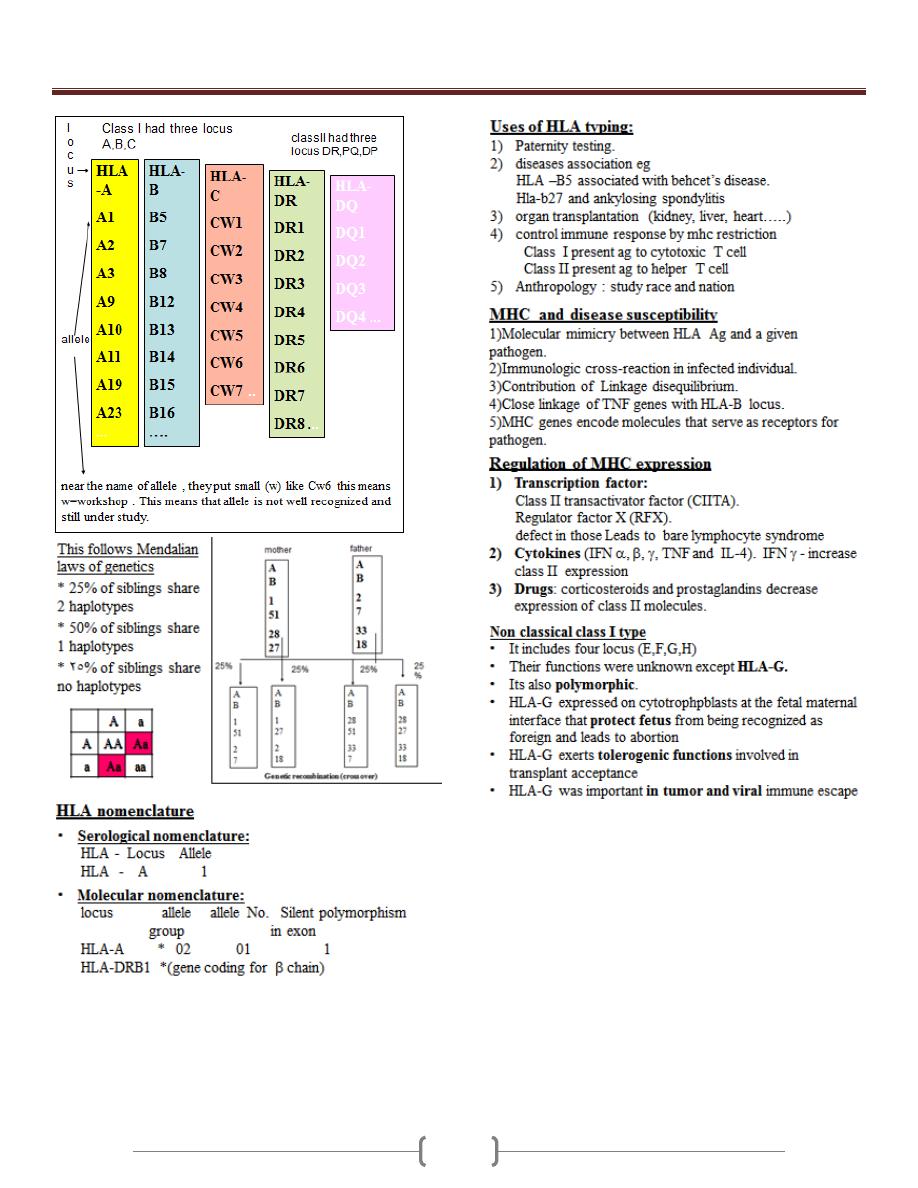

Lecture 4 - Major Histocompatibility

Complex (MHC) & Complement system

Unit 1: Immunology

18

Unit 1: Immunology

19

Unit 1: Immunology

20

Unit 1: Immunology

21

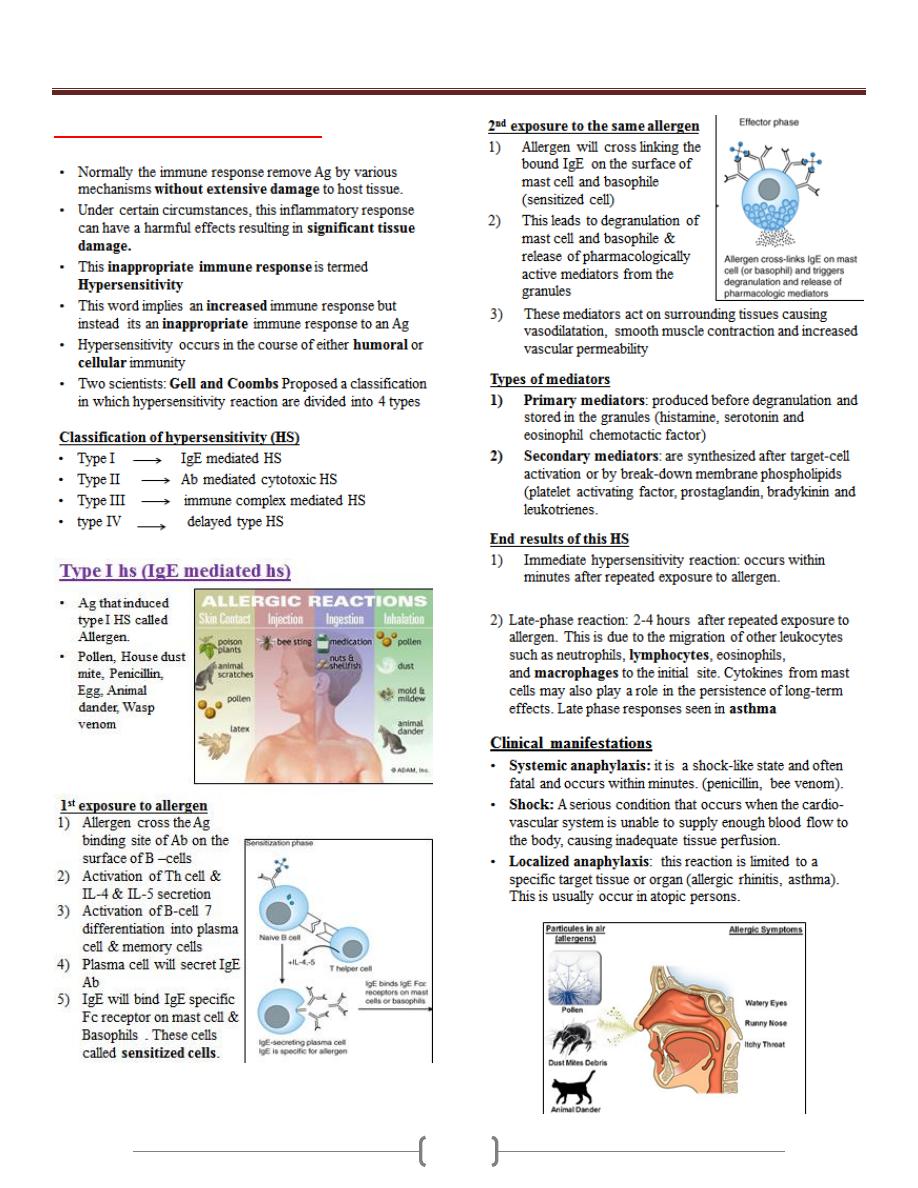

Lecture 5 - Hypersensitivity

Unit 1: Immunology

22

Unit 1: Immunology

23

Unit 1: Immunology

24

Unit 1: Immunology

25

Unit 1: Immunology

26

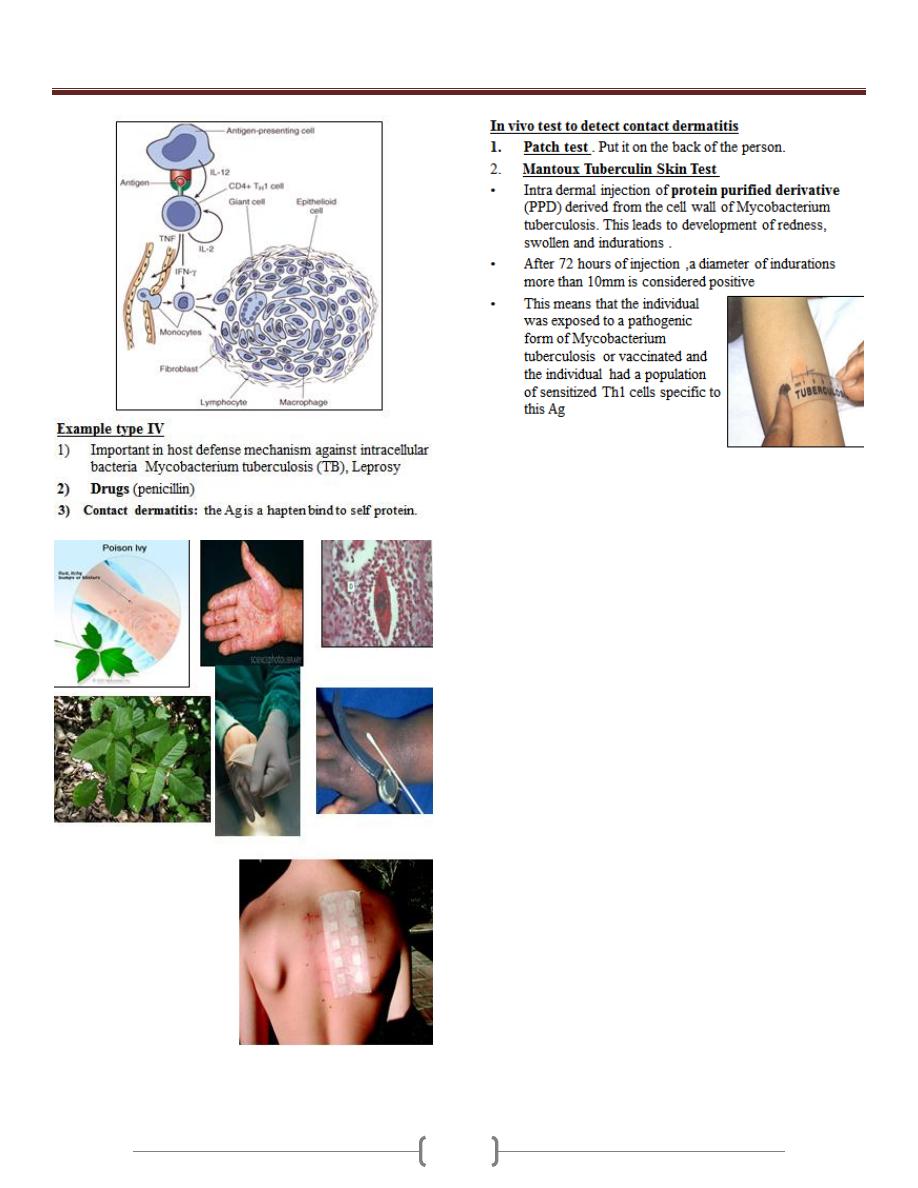

Lecture 6 - Tolerance & Autoimmunity

Unit 1: Immunology

27

Unit 1: Immunology

28

Unit 1: Immunology

29

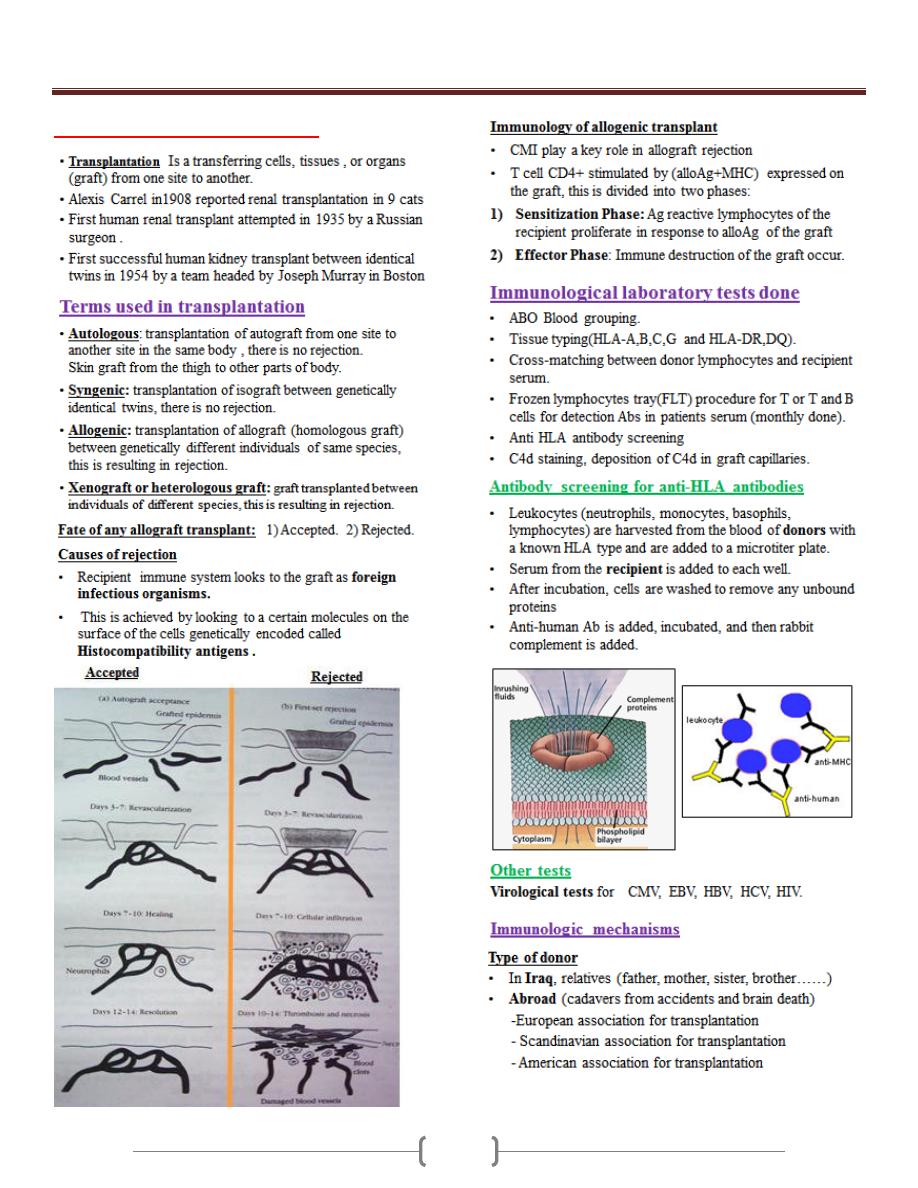

Lecture 7 - Transplantation

Unit 1: Immunology

30

Unit 1: Immunology

31

Unit 1: Immunology

32

Lecture 8+9+10 - Immune response to

infectious diseases

(Viral infection)

Definition of a Virus

Sub microscopic organism consisting of a single nucleic acid

surrounded by a protein coat and capable of replication only

within the living cells of bacteria, human, animals or plants.

It is obligate Intracellular Parasite

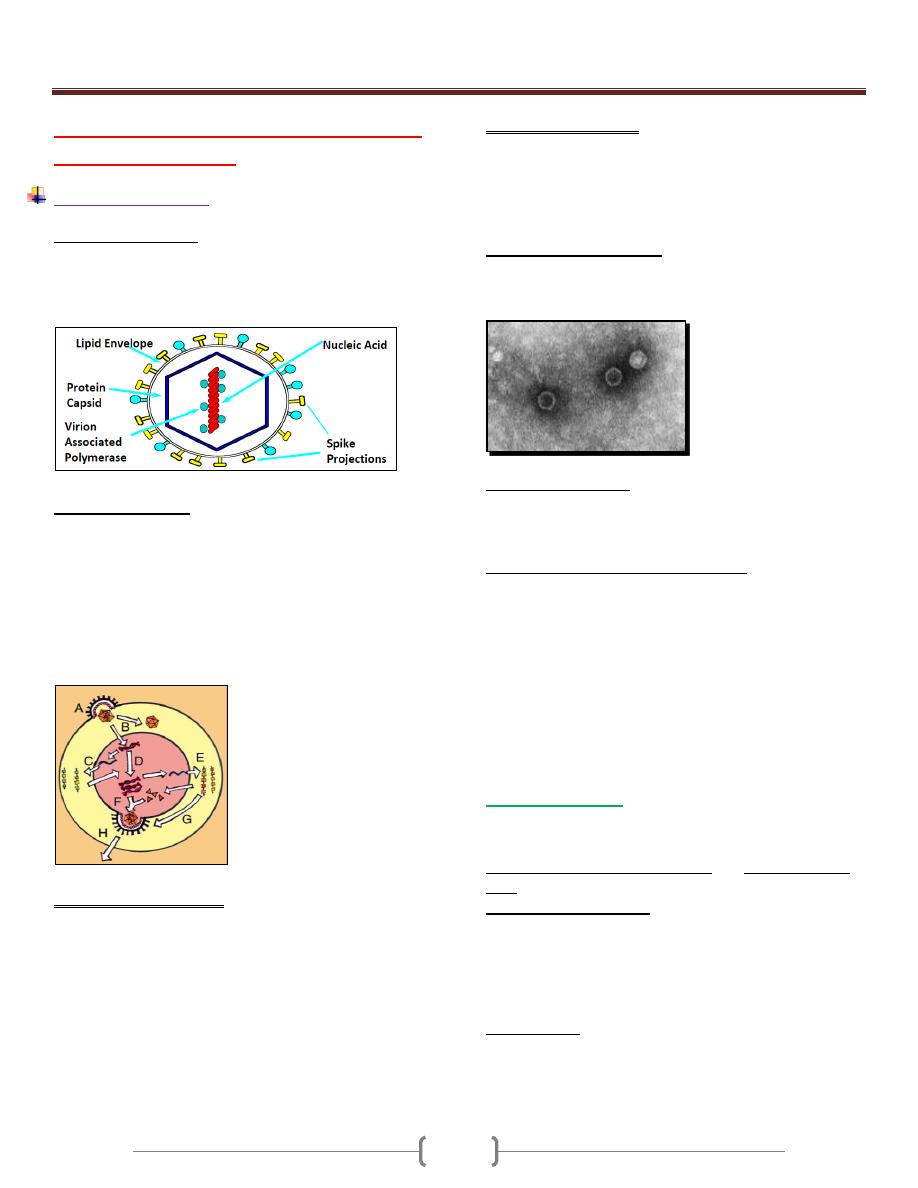

Virus Replication

A. Virus attachment and entry

B. Uncoating of virion

C. Migration of genomic nucleic acid to nucleus, and

Transcrirption

D. Genomic replication

E. Translation of viral mRNA

F and G. Viroin assembly

H. Release of new virus particles

Transmission of Viruses

Respiratory transmission

Influenza A virus

Faecal-oral transmission

Enterovirus

Blood-borne transmission

Hepatitis B virus

Sexual Transmission

HIV

Animal or insect vectors

Rabies virus

Virus Tissue Tropism

Targeting of the virus to specific tissue and cell types

Receptor Recognition

CD4+ cells infected by HIV

CD155 acts as the receptor for poliovirus

In vivo Disease Processes

Cell destruction

Virus-induced changes to gene expression

Immunopathogenic disease

Acute Virus Infections

Localised to specific site of body

Development of viraemia with widespread infection of tissues

Immunity against Viral Infections

Within viruses life cycle they have a relatively short

extracellular period, prior to infecting the cells, and a longer

intracellular period during which they undergo replication.

The immune system has mechanisms which can attack the

virus in both these phases of its life cycle, and which involve

both innate and adaptive effectors mechanisms.

Immunological reactions are thus of two kinds:

Those directed against the virion are predominantly humoral

Those that act upon the virus infected cell are T-cell-mediated.

1) Innate Immunity:

Involves skin, mucous membrane, HCL, enzymes in tears and

secretions, toll-like receptors, but primarily through the

induction of type I interferons (α,β) and activation of NK

cells.

Toll-like receptors (TLR):

TLR allow cells to “see” molecules, it signifying presence of

microbes outside the cell e.g. TLR2, TLR4 and found in

variety of cell types

Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) Intracellular sensing in

monocytes, dendritic cells and lymphocytes

NOD proteins:

Are dipeptides binding intracellular protein, signaling via NF-

κb. These receptors recognize bacterial cell wall components

within cytoplasm

Unit 1: Immunology

33

RIG-I:

Intracellular sensing of RNA viruses e.g. Hepatitis C.

It induces type I interferons

A. Induction of type I interferons (IFN-α and IFN-β).

Are one of the first lines of defense against viral infections. ds

RNA produced during the viral life cycle can induce the

expression of IFN- α and IFN- β by the infected cells leading

to induction of "antiviral response or resistant to viral

replication” by binding to IFN- α / β receptor. They activate

the (JAK-STAT) transcription pathway, which in turn induces

the activation of several genes. One of these genes encodes the

enzyme known oligo-adenylate synthetase which activates a

ribonuclease (RNAse) that degrades viral RNA. and also

blocking viral replication.

B. Natural Killer Cells (NK):

NK cells possess the ability to recognize and lyses virally

infected cells and certain tumor cells.

During the initial stages of infection, NK cells undergo non-

specific proliferation mediated by IFN- α and IFN- β and IL-

12. There is no "lag" phase of clone expansion for NK cells to

be active as effectors, as there is with antigen-specific T and B

lymphocytes. Thus NK cells may be effective within 2 days of

viral infection, and may limit the spread of infection during

this early stage.

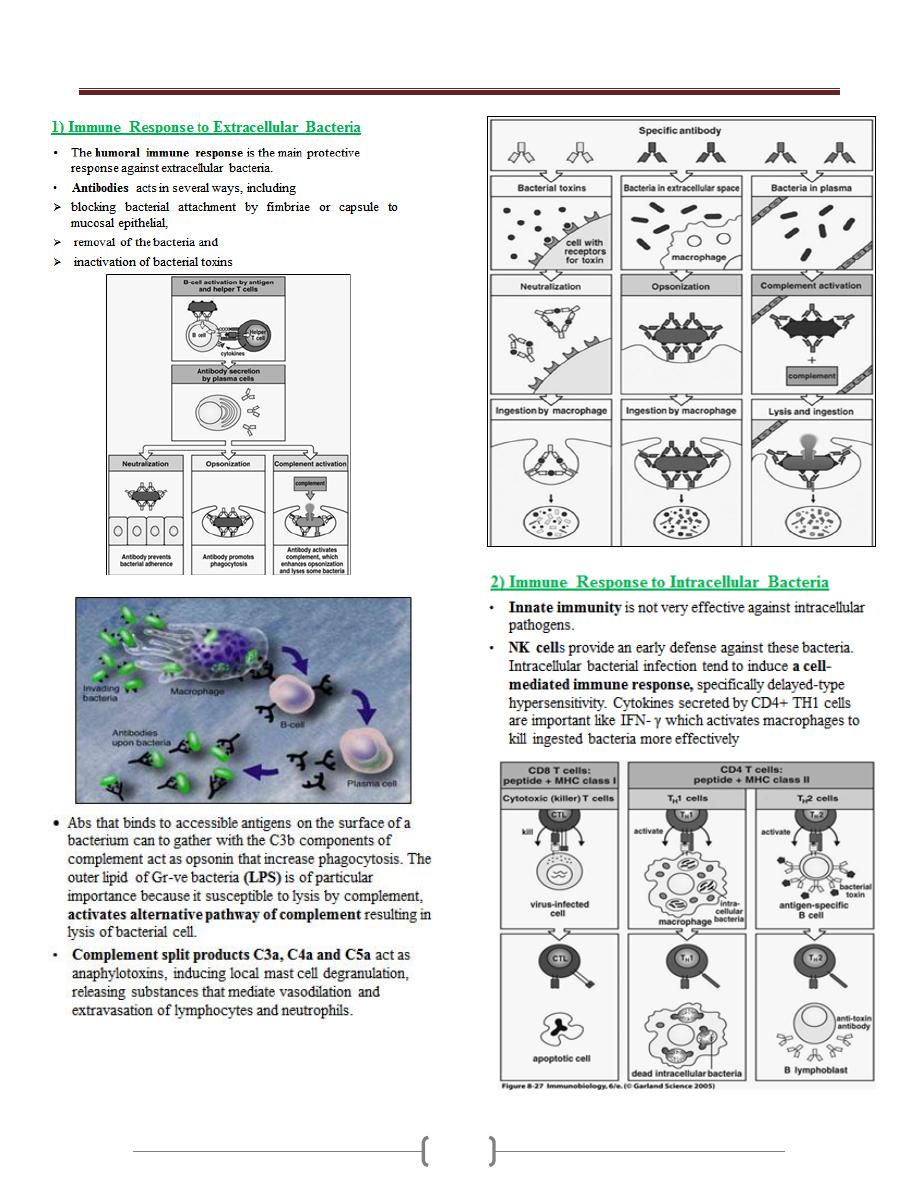

2) Adaptive Immunity:

A. Viral neutralization by humoral antibodies

Antibodies specific for viral surface antigens are crucial in

preventing the spreading of the virus during the acute infection

and in protecting against reinfection.

Secretary IgA (sIgA): blocking viral attachment to mucosal

cells.

IgG, IgM, IgA: blocks fusion of viral envelop to host cell

plasma membrane.

IgG, IgM: enhance phagocytosis by opsonization.

IgM: agglutinates viral particles.

Complement activated by Ag-Ab immune complex leading to

lysis of virus by membrane attack complex and lysis of

enveloped viral particles.

B. Cell mediated immune response mediated by cytotoxic T

lymphocytes (CD8+) that kill virus infected cell, after

induction by activated Th1 cells which produce a number of

cytokines including IL-2, IFN-γ and TNF-α that defends

against viruses either directly or indirectly.

Mechanism of killing of MHC class I- restricted CD8+ CTLs

cells specific for the virus elimination through the release of

perforin and granzymes or through Fas-FasL interaction. CTL

activity arises within 3-4 days, peak by 7-10 days and then

decline.

But in case of persistent virus infection (e.g. hepatitis B

virus), CTLs release IFN-γ and TNF, resulting in clearance

of the virus without death of the cell.

Viral evasion of host- defense mechanism

1)

Some viruses developed strategies to evade the action of IFN-

α/β. These include hepatitis C virus, which binds to IFN

receptor & blocking or inhibiting the action of protein kinase

(PKR).

2)

Herpes Simplex Viruses (HSV) inhibiting antigen

presentation by infected host cells.

HSV -1 and HSV-2 both express an immediate- early protein

that synthesized shortly after viral replication, they effectively

inhibits the human transporter protein TAP needed for

antigen processing, and thus blocks peptide association with

the class I MHC and effectively shut down a CD8+ T- cell

responses to HSV- infected cells.

Unit 1: Immunology

34

Other viruses used this strategies are: Adenoviruses and

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

How can viruses interfere with endogenous Ag processing

as part of the active mechanism of evading immunity?

Herpes zoster virus can remain inactive or in latent state

inside the cell (latency virus genome in sensory ganglion) and

undergoing periodic cycles of activation and replication. The

viral genome remains within the host cell but no expression of

viral antigens occurs. When the host defense is upset perhaps

by other infections, the virus may be activated (it is the most

effective mechanism).

3)

CMV, Measles virus and HIV, have been shown to down

regulation of class II MHC on the cell surface, thus blocking

the function of antigen- specific anti- viral helper T cells.

HIV

4)

Vaccina virus is the prototypic member of the poxvirus

family of cytoplasmic DNA viruses have strategies for

evading complement- mediated destruction, by secretion a

protein that binds to the C4b complement component thus

inhibiting the classical pathway.

HSV have glycoprotein component that binds to C3b

complement components, and inhibiting both the classical

and alternative pathways.

5)

Large number of viruses causing generalized

immunosuppresion.

Either by direct infection of B lymphocytes (e.g. Epestien

Bar Virus), or macrophages (e.g. Measles virus) resulting in

direct lysis of immune cells or alter their function. HIV

destroy CD4+ T cells and macrophages

Some causes cytokine imbalance, (e.g. EBV) inhibits T

lymphocytes by producing a protein termed BCRF1 that is

homologous to IL-10 and thus suppress the cytokine

production by the Th 1 subset, resulting in decreased levels of

IL-2, TNF, and IFN-γ.

Measles Virus binds the complement regulatory protein CD46

(is a human cell receptor for measles virus ) on macrophages.

Example: paramyxoviruses that cause mumps, the measles

virus, epstein- barr virus (EBV), CMV and HIV.

6)

Some viruses escape immune attack by constantly changing

their antigens, as in the Influenza virus, Rhinoviruses, the

causative agent of the common cold, and HIV results in the

frequent emergence of new infectious strains due to mutation

and antigenic variation.

Influenza virus

Properties of the virus

o Myxovirus

o Enveloped virus with a segmented RNA genome

o Infects a wide range of animals other than humans

o Undergoes extensive antigenic variation

o Major cause of respiratory infections

Unit 1: Immunology

35

o Influenza viral particles or virions are spherical in shape

surrounded by an outer envelope, a lipid bilayer. Two

glycoproteins particles inserted into the envelope,

hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), which form

radiating projections.

Hemagglutinin are responsible for the attachment of the

virus to host cells.

Neuraminidase facilitates viral budding from the infected

host cell.

Each virus strain is defined by its animal host of origin or

human, strain number, year of isolation, antigenic

description of HA and NA

o Two different mechanisms generate antigenic variation in HA

and NA:

1. Antigenic drift involves a series of spontaneous point

mutations that occur gradually, resulting in minor changes in

HA and NA.

2. Antigenic shift results in the sudden emergence of a new

subtype of influenza whose HA and possibly also NA are

different from that of the virus present in a preceding

epidemic.

Generation of Novel Influenza A Viruses

o Host response to influenza infection

Humoral antibody specific for the HA molecule is produced

during an influenza infection.

The antibody protects against influenza infection, but its

specificity is strain- specific and is readily bypassed by

antigenic drift.

CTLs can play a role in immune response to influenza.

Unit 1 - Immunology

36

Bacterial infection

Unit 1 - Immunology

37

Unit 1 - Immunology

38

Unit 1 - Immunology

39

Parasitic Infection

Immunity against parasites

Parasites of major medical important successfully adapted

to innate & acquired immune responses of host.

Parasites can cause direct damage to host by:

Competing for nutrients (e.g. tapeworms).

Disrupting tissues (e.g. Hydatid cyst) or destroying

cells (e.g. malaria, hookworm, schistosomiasis; feeding

on or causing destruction of cells causing anaemia).

Mechanical blockage (e.g. Ascaris in intestine).

However, severe disease often has a specific immune or

inflammatory component.

Protozoan Diseases

Protozoans are unicellular eukaryotic organisms. They are

responsible for several serious diseases in humans,

including amoebiasis, African sleeping sickness,

malaria, leishmaniasis, and toxoplasmosis.

Parasitic protozoa may live:

In the gut (e.g. amoebae)

In the blood (e.g. African trypanosomes)

Within erythrocytes (e.g. Plasmodium spp.)

In macrophages (e.g. leishmania spp., Trypanosomes)

In liver and spleen (e.g. leishmania spp.)

Immune responses against protozoan infection

The types of immune response that develop depend on

the location of the parasite within the host.

Many protozoans have life-cycle stages in which they are

free within the blood stream , the humoral antibody is

most effective (e.g. T. brucei)

Unit 1 - Immunology

40

Many of these same pathogens are also capable of

intracellular growth, during these stages, cell mediated

immune reaction are more effective in host defense.

(e.g. Plasmodium malariae (liver and blood stages),

T. cruzi and Leishmamia ( inside macrophages)

Role of Abs in protozoan infection

Antibody responses.

Extracellular protozoa are eliminated by:

Opsonisation and enhance phagocytosis.

Has direct damage, lysis of protozoa by Ag-Ab

immune complex and complement activation.

Intracellular protozoa are

Prevented from entering the host cells by a process of

neutralizing attachment sites, e.g. neutralising

antibody against malaria sporozoites, blocks cell

receptor for entry into liver cells.

Prevents escape from lysosomal vacuoles

Malaria (Plasmodium Species)

It is caused by various spp. of genus Plasmodium, of

which the P. falciparum is the most

virulent. Human infection begins when

sporozoites are introduced into

individual's blood stream as an infected

mosquito takes a blood meal. Then they

migrate to the liver, after that the released

merozoites infect RBCs initiating the symptoms and

pathology of malaria.

Host Response to Plasmodium Infection

In regions where malaria is endemic, the immune

response to plasmodium infection is poor with low

antibody titer.

The type of T cells responsible for controlling an infection

varies with the stage of infection, and depends upon the

kinds of cytokine they produce.

B cells mediate immunity against blood stage

CD8 T cells protect against the liver stage

The action of CD8+ T cells is two folds:

1) They secrete IFN-γ which inhibits the multiplication of

parasites within hepatocytes.

2) They are able to kill infected hepatocytes, but not

infected erythrocytes.

Evasion strategies of Plasmodium

Plasmodium needs time in host to complete complex

development, to sexually reproduce & to ensure vector

transmission.

Chronic infections (from a few months to many years) are

normal; therefore parasite needs to avoid immune

elimination.

Plasmodium has evolved a way of overcoming the

immune response by sloughing off the surface CS-

antigen coat, thus rendering the antibodies ineffective

(immunosupression)

Unit 1 - Immunology

41

The maturational changes from sporoziote to merozoite

to gametocyte allow the organism to keep changing its

surface molecule resulting in continual changes in the

antigen seen by the immune system.

African sleeping sickness (Trypanosoma

Species)

Two spp. of African trypanosomes (Trypanosoma brucei,

Trypanosoma cruzi), which are flagellated protozoan,

can cause sleeping sickness, it transmitted to humans and

cattle by the bite of tsetse fly.

The disease beginning with an early (systemic) stage in

which trypanosomes multiply in the blood and

progressing to a neurologic stage in which the parasite

infects the CNS causing meningeoecephalitis.

Host Response to Trypanosoma Infection

Humoral antibody

African Trypanosomes have one surface glycoprotein that

covers the parasite. This protein is immunodominant for

antibody responses .

The glycoprotein coat, called variant surface

glycoprotein (VSG).

These Abs eliminate most of the parasites from the blood

stream both by complement- mediated lysis and by

opsonization and subsequent phagocytosis.

However about 1% of the organisms which bear an

antigenically different VSG escape the initial Abs

response.

Evasion strategies of Trypanosoma

1) Antigenic variation

Trypanosoma brucei have “gene cassettes” of variant

surface glycoproteins (VSG’s) which allow them to

switch to different VSG.

Several unusual genetic processes generate the

extensive variation in trypanosomal VSG that enable

the organism to escape the immunological clearance.

VSG gene is switched regularly. The effect of this is

that host mounts immune response to current VSG

Abs but parasite is already switching VSG to another

type which is not recognised by the host. A parasite

expressing the new VSG will escape antibody

detection and replicate to continue the infection.

This allows the parasite to survive for months or years.

Up to 2000 genes involved in this process.

This type of antigenic variation is known as

phenotypic variation and is in contrast to genotypic

variation in the case of influenza virus in which a new

strain periodically results

2) Suppression of the immune response, e.g.

Trypanosoma cruzi produces molecules that either inhibit

the formation or accelerate the decay of C3 convertase, so

blocking complement activation on the parasite surface.

Leishmaniasis:

For Intra cellular protozoa

Leishmania major is a protozoan that

lives in the phagosomes of

macrophages.

Resistance to the infection correlates

with the cytokines secreted from TH1

and activation of Macrophages by

IFN-γ and TNF-α and killing by

Nitrous oxide and O2 metabolites

Unit 1 - Immunology

42

Immune evasion mechanisms of Intracellular protozoa

There are three main ways in which protozoa can evade or

modify the host's immunological attack:

1. Antigenic modulation

2. Resistance to macrophages killing

3. Suppression of the immune response

Protozoan immune evasion strategies

1. Leishmania can evade the immune surveillance by

Antigenic modulation, which can rapidly change their

surface coat (cap off) within minutes of exposure to

antibodies, so becoming refractory to the effects of

antibodies and complement.

2. Toxoplasma has evolved mechanisms which prevent

fusion of phagocytic vacuoles with lysosomes and resist

to macrophages killing.

3. Leishmania produce anti-oxidases to counter products of

macrophage oxidative burst, resist lysosomal enzymes

and suppressed the immune responses

Parasitic Worms (Helminthes)

Too large for phagocytosis BUT Immune response can

activate inflammation which results in expulsion of

worms.

Anti-worm IgE can activate degranulation of mast cells

and eosinophils leads to Type I hypersensitivity like

responses.

Initiation of response is poorly understood. Unusual

carbohydrates can be recognized by innate and adaptive

(antibody) responses. These responses are regulated by

the TH2 subsets of CD4 T lymphocytes.

The immunological responses in helminthes diseases

1) High titer of IgE that induced by a substance released

from the parasite acting as B cell mitogens.

2) Accumulation of mast cell and degranulation of these

cells releasing Eosinophils chemotactic factor (ECF),

Neutrophil chemotactic factor (NCF)

3) cytokines secretion by Th2 :

IL-4 induces B-cells to class switching to IgE

production ,

IL-5 induces bone marrow precursors to differentiate

into Eosinophils ,

IL-13 stimulates growth of mast cells

4) Ab- Ag complex activates complement ending in cell lysis

5) The eosinophils express Fc receptors for IgE and IgG and

bind to the Ab- coated parasite. Once bound to the

parasite, an eosinophil can participate in Ab- dependent

cell- mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), releasing mediators

from its granules called Major basic protein (MBP) that

is toxic to helminthes causing small holes in the surface of

the helminth.

6) Neutrophils and macrophages act by releasing toxic O2

and N2 metabolites

7) In case of Nematodes, there is proliferation and

stimulation of goblet cells, increased mucus secretion

leads to expulsion of worm

Unit 1 - Immunology

43

Helminth immune evasion strategies

1) Antigenic disguise: (e.g. Adult Schistosoma)

Decrease expression of Ag on its outer surface.

Enclosed itself in a glycolipid and a glycoprotein coat

derived from the host , masking its own Ags Like

ABO blood group Ags

2) Suppression of T- & B- cell responses: young schistosomes

actively protect themselves by releasing peptidases that

cleave bound immunoglobulin & other factors that inhibit

both T-cell proliferation 7 release of IFN-γ or the mast cell

signal required for eosinophil activation.

3) Location inside the lumen of the gut like nematodes or

encysted inside protective cyst like Trichenella spirallis.

4) Presence of a thick extracellular cuticle like tegument

of Schistosomes which protect them from the immune

system

5) Molecules production that interfere with host immune

function e.g. Filarial worms secrete a protease inhibitor

Filarial worm evasion of immune responses

Compare between immune response to protozoa

and helminthes

Fungal Infection

Fungi are eukaryotes with a rigid cell wall enriched in

complex polysaccharides such as chitin, glucans. Among

the 70000 species of fungi, only a small number are

pathogenic for humans.

Fungal infections are regularly seen in:

* Patients with untreated AIDS.

* Patients with cancer and undergoing chemotherapy.

* Patients with transplants on immunosuppressive agents.

* Some patients taking long-term corticosteroids.

Degree of fungal infection can range from cutaneous to

deep and systemic

Unit 1 - Immunology

44

Lecture 4+5+6 - Immunodeficiencies

Definition

It is a condition in which the immune system is failed to

protect the host from disease-causing agents or from

malignant cells.

Immunodeficiency disease results from the absence or

failure of normal function of one or more elements of the

immune system.

The immunodeficiencies should be suspected in every

patient, irrespective of age, who has recurrent, persistent,

sever or unusual infections.

Classification

A. Primary immunodeficiency: a condition results from a

genetic or developmental defect in immune system

(intrinsic defect). In such a condition, the defect is present

at birth although it may manifest itself later in life.

B. Secondary immunodeficiency or (acquired

immunodeficiency): is the loss of immune function and

results from exposure to various agents (disease or therapy).

The most common one is acquired immune-deficiency

syndrome or AIDS, which results from infection with the

human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1).

1) Primary immunodeficiency

Primary immunodeficiencies may affect either adaptive or

innate immune functions.

Specific immunodeficiency diseases involve

abnormalities of T or B cells, the cells of the adaptive

immune system.

Non-specific immunodeficiency diseases involve

abnormalities of elements such as complement proteins or

phagocytes, which act non-specifically in immunity..

Immunodeficiency diseases cause increased susceptibility

to infection in patients. The infections encountered in

immunodeficient patients fall into two categories:

Patients with defects in immunoglobulins, complement

proteins or phagocytes are very susceptible to recurrent

infections with encapsulated bacteria such as

Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae and

Staphylococcus aureus. These are called pyogenic

infections, because the bacteria give rise to pus formation.

On the other hand, patients with defects in cell-

mediated immunity, in T cells, are susceptible to

overwhelming, even lethal; infections with opportunistic

microorganisms include yeast and common viruses such

as chickenpox.

Defects in the lymphoid Lineage

A. Primary B-cell deficiencies include:

Patients with common defects in B-cell function have

recurrent pyogenic infections such as pneumonia, otitis

media and sinusitis

1) X- Linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA) early

B- cell maturation fails

Affected males have few or no B cells in their blood or

lymphoid tissue; their lymph nodes are very small and

their tonsils are absent. Their serum usually contains no

IgA, IgM, IgD or IgE, and only small amounts of IgG

(less than 1 md/dl). Infants for the first 6 – 12 months of

life are protected from infection by the maternal IgG. As

this supply of IgG is exhausted, affected male develop

recurrent pyogenic infections.

The gene that is defective in X-LA is a B-cell cytoplasmic

tyrosine kinase (btk) belonging to the src oncogene family.

It encoded B- cell signal transduction molecule called

Burton’s tyrosin kinase is obviously vital for the process of

B-cell maturation. Bone marrow of males with X-LA

contains normal numbers of pre-B cells but, as a result of

mutations in the btk gene, they cannot mature to B cells.

Treatment by periodic Intravenous administration of Igs

Unit 1 - Immunology

45

2) X- Linked Hyper IgM Syndrome (XHM)

In XHIgM the B cells cannot make the switch from IgM

to IgG, IgA and IgE synthesis that normally occurs in B-

cell maturation.

As a result, patients have decreased levels of serum IgG

and IgA and elevated levels of IgM some times as high as

10 mg/ml (normal Igm concentration is 1.5 mg/ ml).

It results from a variety of genetic defects that affect the

interaction between T-lymphocytes and B-lymphocytes.

It is inherited as an X- linked recessive disorder.

In normal B cells, this switch to IgE is induced by two

factors:

IL-4 must bind to the B-cell receptor for IL-4, and

The CD40 molecule on the B-cell surface must bind to

the CD40 ligand on activated T cells.

70% is due to defect in the gene encoding the CD40

ligand (CD40L) on the membrane of TH cells

Children in first two years suffer recurrent infections,

especially respiratory infections caused by opportunistic

pathogens.

Treatment by administration of intravenous Ig.

3) Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID)

There are defect in T cell signaling to B cells.

Individuals with CVID have acquired

agammaglobulinaemia in the second or third decade of

life, or later. Both males and females are equally affected

and the cause is generally not known, but may follow

infection with viruses such as Epstein – Barr virus (EBV).

Patients with CVID, like males with X-LA, are very

susceptible to pyogenic organisms.

Most patients (80%) with CVID have B cells that do not

function properly and are immature. The B cells are not

defective; instead, they fail to receive proper signals from

the T cells.

Patients with CVID should be treated with intravenous

gammaglobulin.

4) Selective IgA deficiency

B. Primary T-cell deficiencies include:

1) Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID):

Infants with SCID have very few lymphocytes in their

blood (fewer than 3000/ml). Their lymphoid tissue also

contains few or no lymphocytes. The thymus has a fetal

appearance.

Patients with no T cells, or poor T-cell function, are

susceptible to opportunistic infections. Since B-cell

function in humans is largely T-cell dependent, T-cell

deficiency also results in humoral immunodeficiency.

The infants have prolonged diarrhea due to rotavirus or

bacterial infection of the GIT, and develop pneumonia

usually due to protozoal infection.

The common yeast organism Candida albicans grows in

the mouth or on the skin of the patients with SCID.

If the patients with SCID are vaccinated with live

organisms such as poliovirus or BCG they die from

progressive infection with these organisms

Unit 1 - Immunology

46

1. Over 50% of cases are caused by a gene defect on the X

chromosome. SCID is more common in males than

females infants (3:1)

Genetic defect in γ-chain of the IL-2R also shard

receptors for other cytokines IL-4, 7, 11, and 15.

2. The remaining cases of SCID are due to recessive genes

on other chromosomes of these, half have a genetic

deficiency of adenosine deaminase (ADA) or purine

nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP), resulting in the

accumulation of metabolites that are toxic to lymphoid

stem cells. These metabolites inhibit the enzyme

ribonucleotide reductase, which is required for DNA

synthesis and for all replication.

3. Other autosomal recessive form of SCID results from a

mutation in either of the recombinase- activating genes

encoding RAG-1 or RAG-2.

These two genes are absolutely required for cleaving

double- stranded DNA before recombination of DNA

to form the immunoglobulin genes and the genes

encoding the lymphocyte cell receptor that

characterized mature B and T cells.

If these gene rearrangements do not occur, B and T

cells do not develop.

The optimal treatment: is a bone marrow transplant from a

completely histocompatible donor, usually normal sibling,

or the affected infants die within the first 2 years of life.

Also gene therapy of RAG

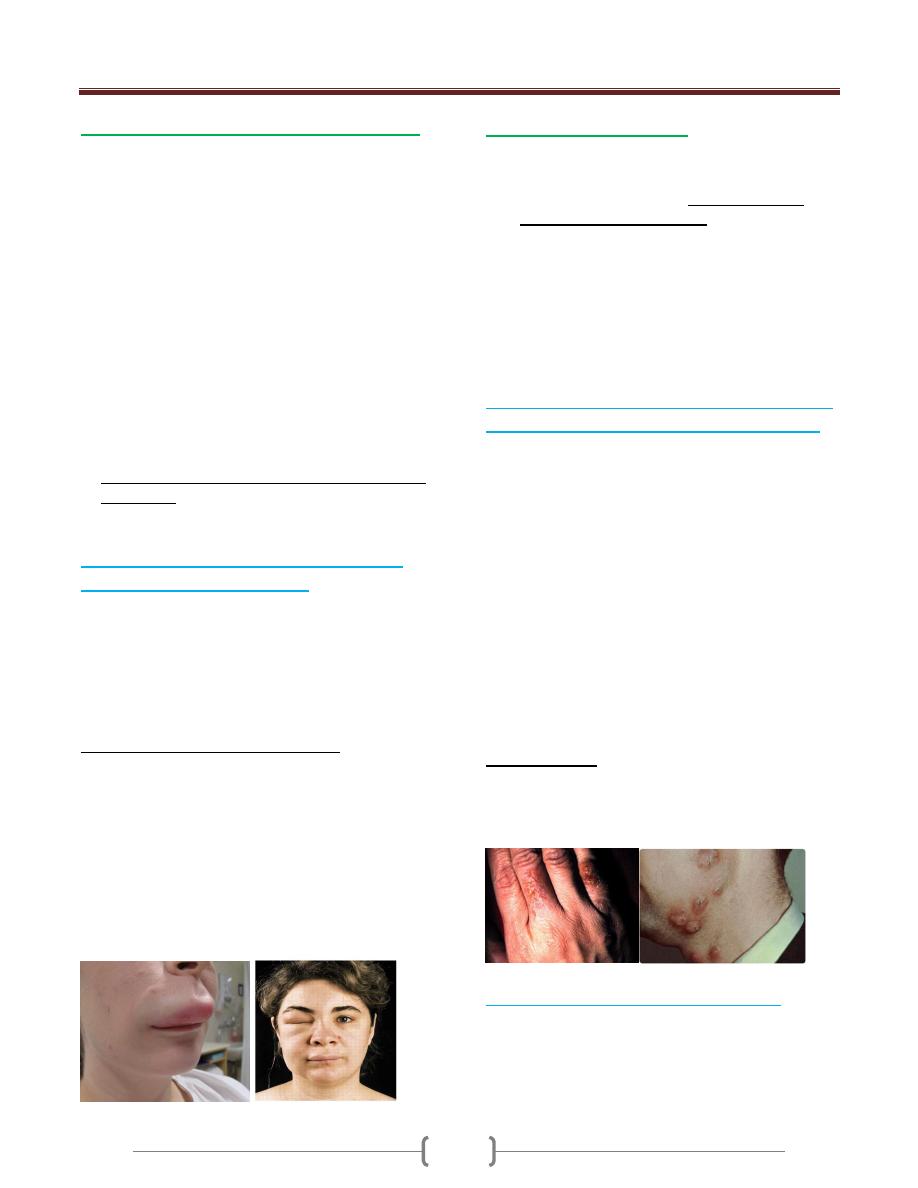

2) The DiGeorge Syndrome (Congenital Thymic

Aplasia)

The thymic epithelium is derived from the third and

fourth pharyngeal by the sixth week of human gestation.

Defect is associated with the deletion in the embryo of a

region on chromosome 22

The T-cell deficiency is variable, depending on how badly

the thymus is affected. Affected infants have distinctive

facial features in that their eyes are widely separated.

They also have congenital malformations of the heart or

aortic arch and neonatal tetany from the hypoplasia or

aplasia of the parathyroid glands.

Treatment is by supportive therapy, or thymic

epithelial transplant.

3) Wiskott- Aldrich Syndrome (WAS):

WAS is an X-linked immunodeficiency disease.

Affected males have small and abnormal platelets, which

are also few in numbers (thrombocytopenia) which may

lead to fatal bleeding. Boys with WAS develop severe

eczema as well as pyogenic and opportunistic infections.

Their serum contains increased amounts of IgA & IgE,

normal levels of IgG and decreased amounts of IgM.

Their T cells are defective in function. This fails to

occur in the WAS, with the result that collaboration

among immune cell is faulty.

Unit 1 - Immunology

47

C. Genetic Defect in Complement Proteins

Deficiencies of the classical pathway components, C1q,

C1r, C1s, C4, or C2 results in susceptibility to develop

immune complex disease such as systemic lupus

erythematosus (SLE). This correlates with the known

function of the classical pathway in the dissolution of

immune complexes.

Deficiencies of C3, and the alternative pathway

components, factor H, or factor I result in increased

susceptibility to pyogenic infection; this correlates with

the important role of C3 in opsonization of pyogenic

bacteria.

Deficiencies of the terminal components C5-8, and of

the alternative pathway components, factor D and

properdin results in remarkable susceptibility to

infection with two pathogenic spp. Of Neisseria,

gonorrhoeae, and meningitides.

All these genetic complement component deficiencies

are inherited.

Treatment usually maintained with antibiotics.

Hereditary angioneurotic edema (HAE) is

due to C1 inhibitor deficiency

It is well-known disease resulted due to deficiency of the

complement system C1 inhibitor. This molecule is

responsible for dissociation of activated C1, by binding to

C1r2 and C1s2.

This disease is inherited as an autosomal dominant

trait

C1 inhibitor deficiency may be acquired later in life. In

some cases an autoantibody to C1inhibitor is found.

Patients with HAE have recurrent episodes of swelling of

various parts of the body (angioedema). When the edema

involves the intestine, abdominal pains ad cramps results,

with severe vomiting.

When the edema involves the upper airway, the patients

may choke to death from respiratory obstruction.

Angioedema of the upper airway therefore presents a

medical emergency, which requires rapid action to restore

normal breathing.

D. Defects in phagocytes

Phagocytic cells – polymorphonuclear leucocytes and

cells of the monocyte /macrophage lineage – are

important in host defense against pyogenic bacteria and

other intracellular microorganisms. A severe deficiency

of polymorphonuclear leucocytes (neutropenia) can result

in overwhelming bacterial infection.

Two genetic defects of phagocytes are clinically

important in that they result in susceptibility to severe

infections and are often fatal includes:

1. Chronic granulomatous disease

2. Leucocyte adhesion deficiency.

1) Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is due

to a defect in the oxygen reduction pathway

Is a genetic disease, 70% is an X- linked form

Defect in the ability of macrophages and PMNs to kill

phagocytosed organisms

Decrease in the ability of macrophages to serve as APCs.

Patients with CGD have defective NADPH oxidase

which catalyzes the reduction of O

2

to •O

2

by the

reaction:

NADPH + 2O

2

→ NADP

+

+ 2•O

2-

+ H

+

Thus, they are incapable of forming superoxide anions

(•O

2

) and hydrogen peroxide in their phagocytes,

following ingestion of microorganisms and so cannot

readily kill ingested bacteria or fungi organisms.

As a result, microorganisms remain alive in phagocytes of

patients with CGD. This gives rise to a cell-mediated

response to persistent intracellular microbial antigens, and

granulomas form. Children with CGD develop

pneumonia, infections the lymph nodes (lymphadenitis),

and abscesses in the skin, liver and other viscera.

Treatment with antibiotics

2) Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency (LAD)

The receptor in the phagocyte membrane that binds to

C3b on opsonized microorganisms is critical for the

ingestion of bacteria by phagocytes. This receptor, an

integrin called complement receptor 3 (CR3), is

deficient in patients with LAD and consequently they

Unit 1 - Immunology

48

develop severe bacterial infections, particularly of the

mouth and GIT.

CR3 is composed of two polypeptide chains: an α chain

and β chain. In LAD, there is a genetic defect of the β

chain of CR3, encoded by a gene on chromosome 21.

Other integrin proteins share the same β chain, namely

lymphocyte function associated antigen (LFA-1) .

Genetic defect of LFA-1 leading to impairment of

adhesion of leukocytes to vascular endothelium and limits

recruitment of cells to sites of inflammation.

LAD varies in its severity; some affected individuals die

within a few years, whereas others may survive into their

forties.

2) Secondary or Acquired

Immunodeficiency

It results from exposure to a number of chemical &

biological

agents that induce immunodeficient state.

A. Drugs:

Corticosteroids: commonly used for treatment of

autoimmune disorders interfere with the immune response

in order to relief the disease symptoms

Immunosuppressive drugs, such as cyclosporine- A

used in transplantation patients which block the immune

attack to transplanted organ.

Cytotoxic drugs or radiation treatments given to treat

various forms of cancer frequently damage the dividing

cells in the body (depression hematopoiesis)

B. Nutrient Deficiency

Lymphoid tissues are very vulnerable to the damaging

effects of malnutrition.

Numerous enzymes with key roles in immune processes

required zinc, iron, vitamin B6, and other

micronutrients including selenium, and copper.

Lymphoid atrophy is a prominent morphological feature

of malnutrition (T selective deficiencies)

C. Infection:

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS):

The most significant global cause of immunodeficiency is

HIV infection. Over 25 million people have died from

AIDS since the first cases were described in 1981. As the

end of 2004, WHO estimate that, approximately 40

million people are living with HIV infection worldwide,

with approximately 5 million new infections and 3 million

deaths each year.

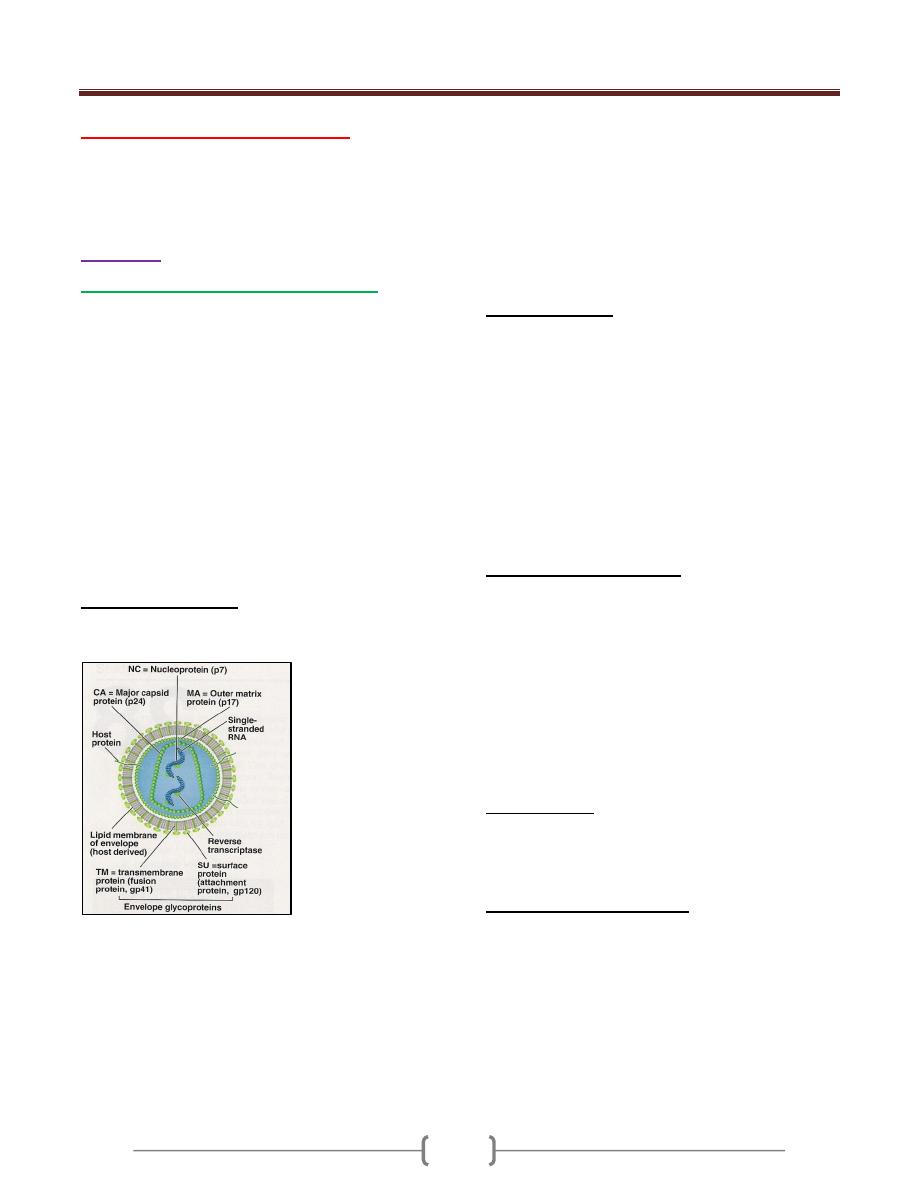

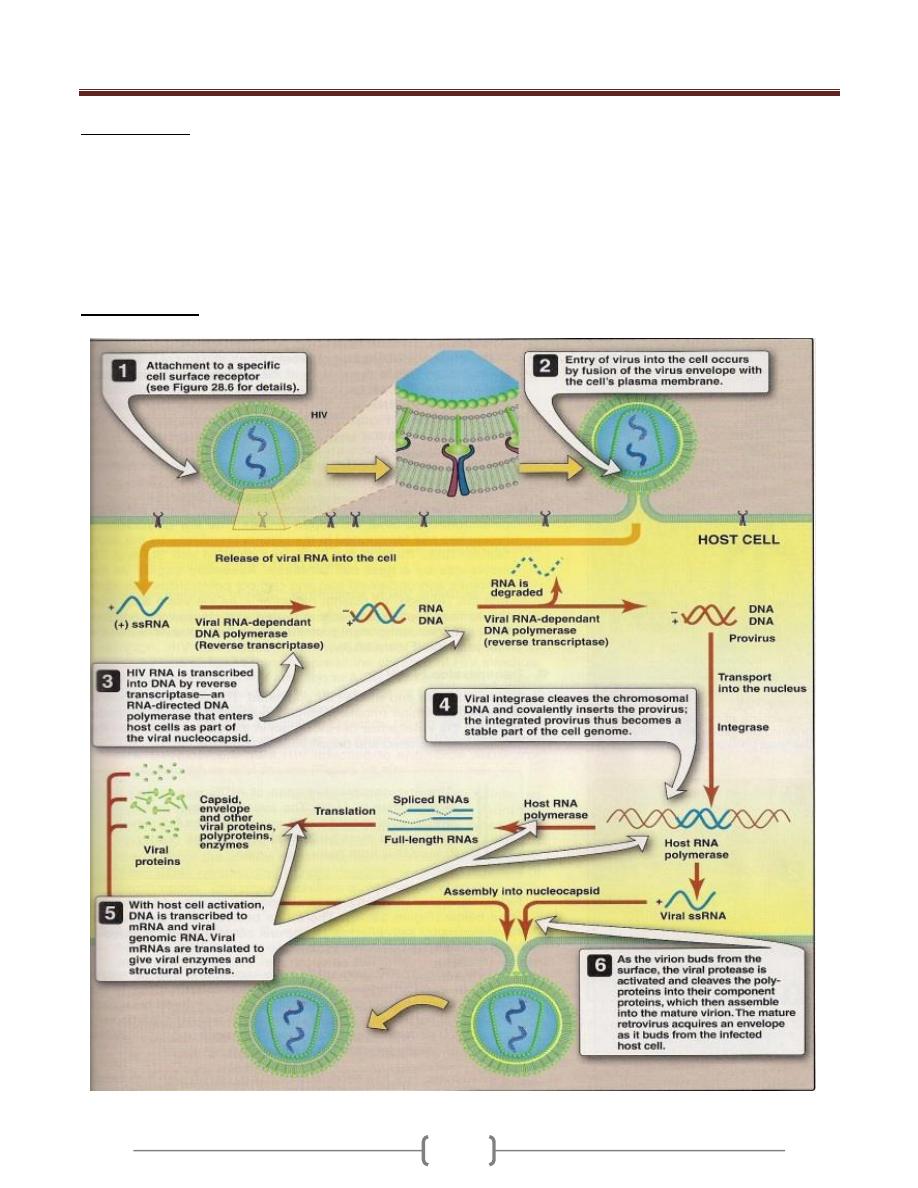

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

AIDS: Is caused by Human Immunodeficiency Virus

(HIV) a retrovirus, which is found in all cases of the

disease.

The primary targets of HIV are activated CD4+ T helper

lymphocytes but the virus can also infect several other

cell types including macrophages.

Infection leads to loss of T4 helper lymphocytes and

immunosuppression in the patient and the consequent

fatal opportunistic infections.

HIV is a lentivirus, a class of retrovirus.

The name lentivirus means slow virus, so called because

these viruses take a long time to cause overt disease.

Most lentiviruses target cells of the immune system and

thus disease is often manifested as immunodeficiency

Unit 1 - Immunology

49

There are two types of HIV: HIV-1 and HIV-2. These

cause clinically indistinguishable disease, although the

time to disease onset is longer for HIV-2.

The worldwide epidemic of HIV and AIDS is caused

by HIV-1 while HIV-2 is mostly restricted to west Africa

CD4 antigen is the main receptor for the virus entry, and

is present on CD4+ T lymphocytes and monocytes.

The binding of the viral envelope glycoprotein gp120 to

CD4 antigen results in conformational changes in gp120

that expose binding sites for chemokine receptors, which

serve as co-receptors for viral entry, these includes CCR5

and CXCR4

The disease is appeared at the first time in 1981, as clusters

of cases of Kaposi's sarcoma were reported in young

patients in San Francisco and New York. This was an

unusual occurrence since, in the United States, Kaposi's

sarcoma was a rare disease that normally occurred in

elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean ancestry. however,

these new clusters of patients were all young male

homosexuals and the disease was much more aggressive

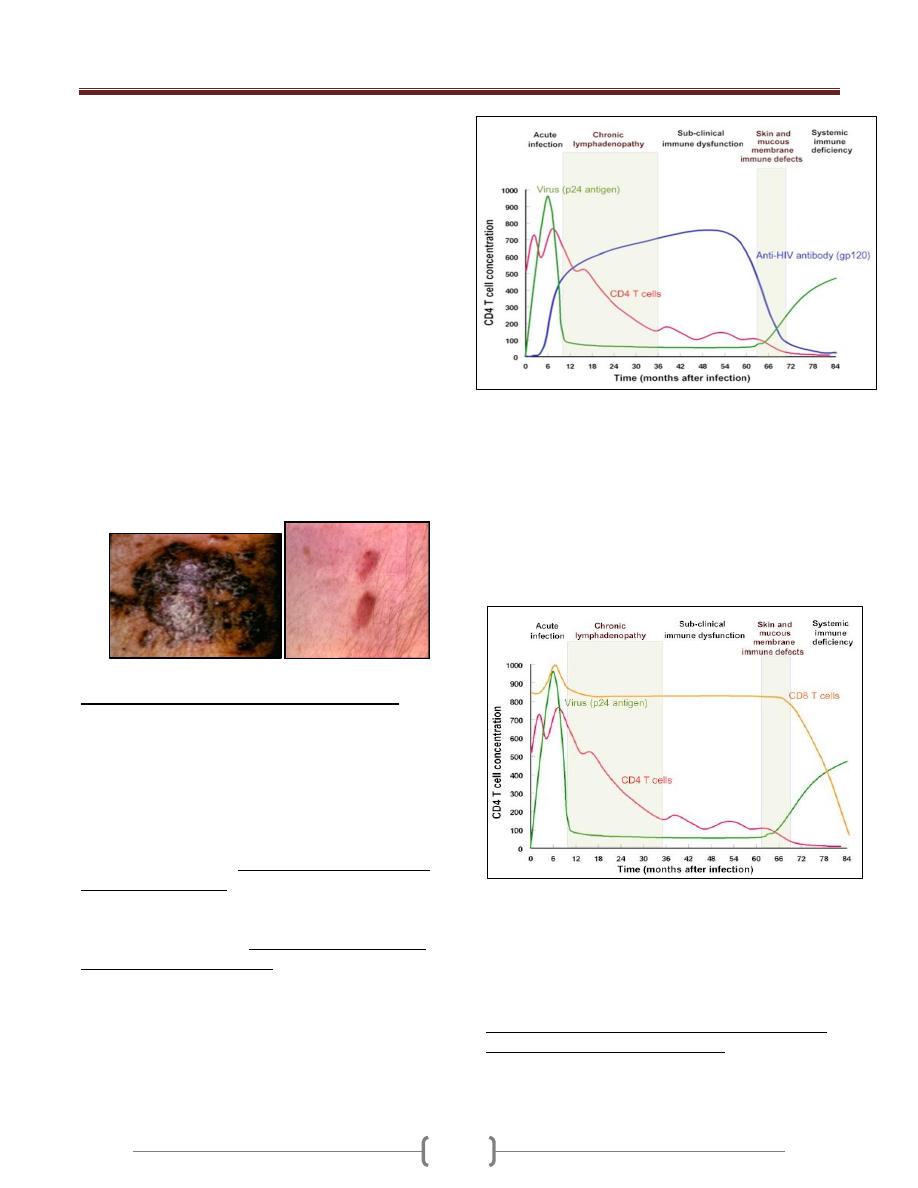

Immune Responses against HIV infection

Cell-mediated and humoral anti-HIV immune defense:

Cytotoxic T and B lymphocytes mount a strong defense

and virus largely disappears from the circulation.

Virus titer, CD4T cells and anti-gp120 titer during the

HIV infection

After the increased cell-mediated immune response, there

is a rise in antibodies in the serum of infected individuals

2-3 weeks after infection, but though these lack the ability

to inhibit viral infection. During this period, more than 10

billion new HIV particles are produced each day. They are

rapidly cleared by the immune system especially anti-

HIV antibody (gp120). So neutralizing antibodies play a

role in controlling HIV viremia.

Despite the presence of high numbers of HIV specific

CTLs in the peripheral blood, but like antibody

responses unable to eliminate infection.

At this stage, most of this virus is coming from

recently infected proliferating CD4

+

cells. Thus, the

virus is destroying the cells that are proliferating.

The infected cells that are producing this virus are

destroyed either by the immune system or by the virus

and have a half-life about 1 day.

Although activated, proliferating CD4+ cells are

destroyed by the immune system, a small fraction of the

infected cells survive long enough to revert back to the

resting memory state (as do non-infected CD4

+

memory cells).

The resting memory cells do not express viral antigens but

do carry a copy of the HIV genome which remains latent

until the cells are reactivated by antigen. These memory

cells may survive many years and constitute a

reservoir that is very important in drug-based

therapy.

Unit 1 - Immunology

50

During this period, the virus disseminates to other regions

including to lymphoid and nervous tissue. This is the most

infectious phase of the disease.

Loss of CD4

+

cells & collapse of the immune

response

During the course of infection, there is a profound loss of

the specific immune response to HIV because:

Responding CD4+ cells become infected. Thus, there is

clonal deletion leading to tolerance and escape of HIV

from the immune surveillance.

Activated CD4+ T cells are susceptible to apoptosis.

Spontaneous apoptosis of uninfected CD4

+

and CD8

+

T

cells occurs in HIV-infected patients.

Also there appears to be selective apoptosis of HIV-

specific CD8

+

cells

the number of follicular dendritic cells falls over time,

resulting in diminished capacity to stimulate CD4+ cells

More severe infections are associated with a low

CD+4 T cell count

It is the phase of the disease that lacks the neoplasms and

opportunistic infections that are the definition of AIDS

Patients at this stage of the disease show weight loss and

fatigue together with fungal infections of the mouth,

finger and toe nails especially with Candida

Orofacial

granulomatos

is with cobble

stone mucosa

in AIDS

Facial

sarcoidosis

in AIDS

Opportunistic

infections that

are the definition

of AIDS

Unit 1 - Immunology

51

Lecture 7 – Tumor Immunology

Unit 1 - Immunology

52

Unit 1 - Immunology

53

Unit 1 - Immunology

54

Lecture 8 – Vaccines

Unit 1 - Immunology

55

Unit 1 - Immunology

56

Making of DNA Vaccine against West Nile Virus

Unit 1 - Immunology

57

58

59

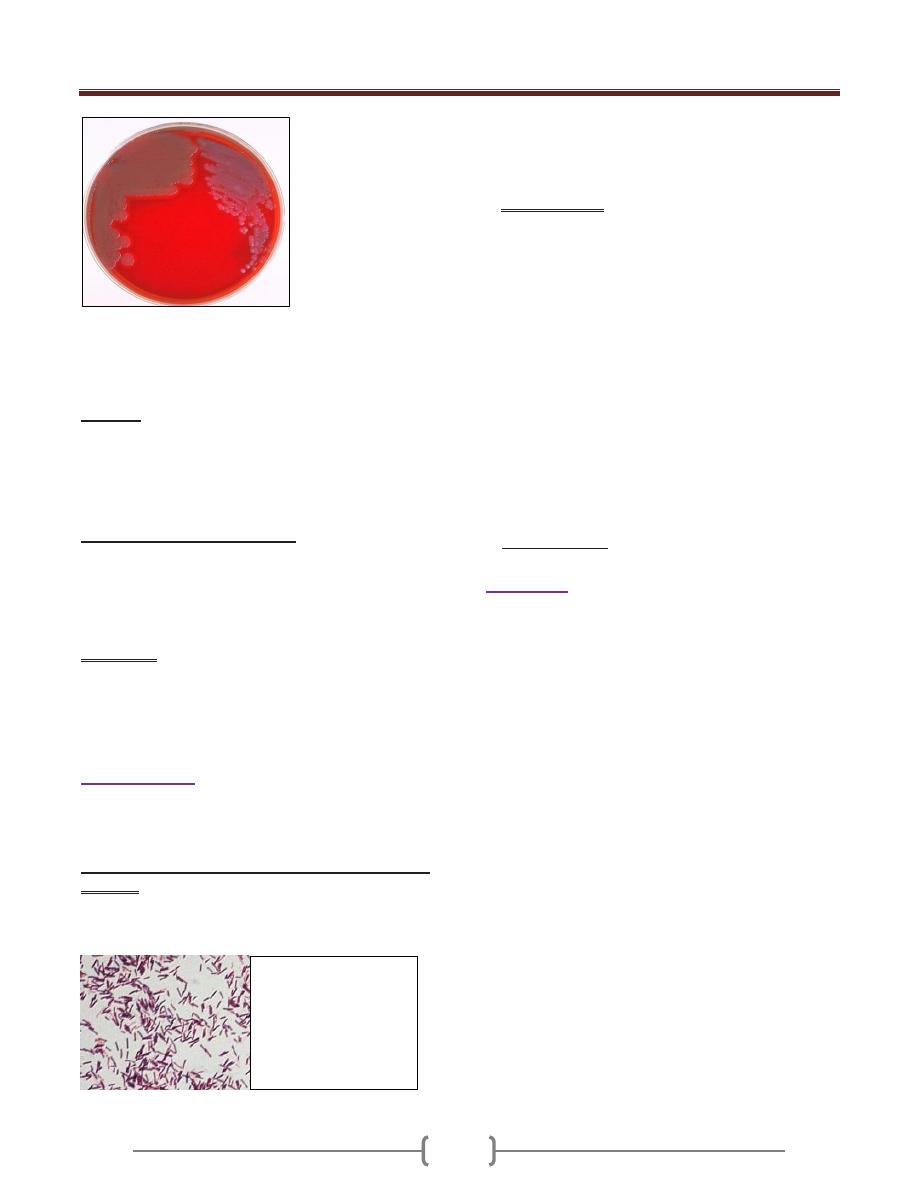

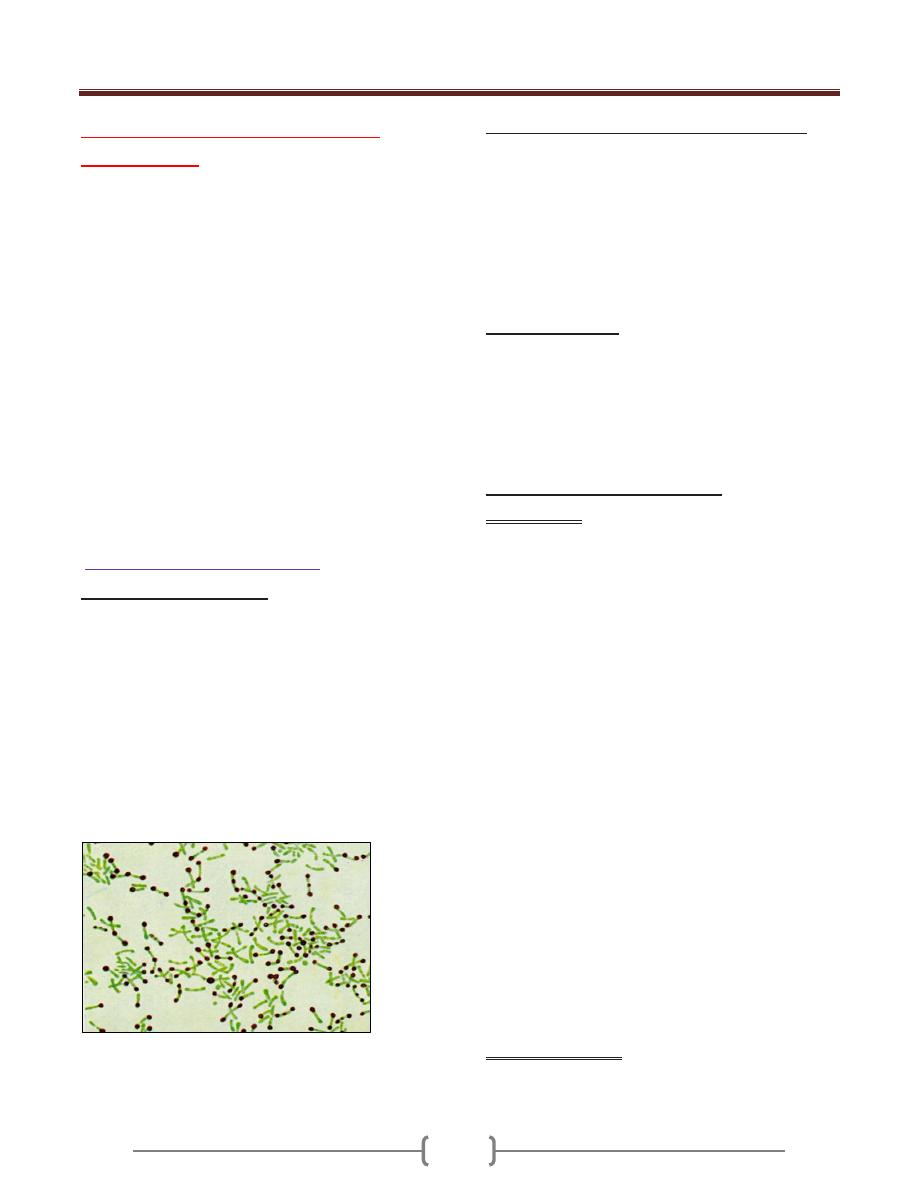

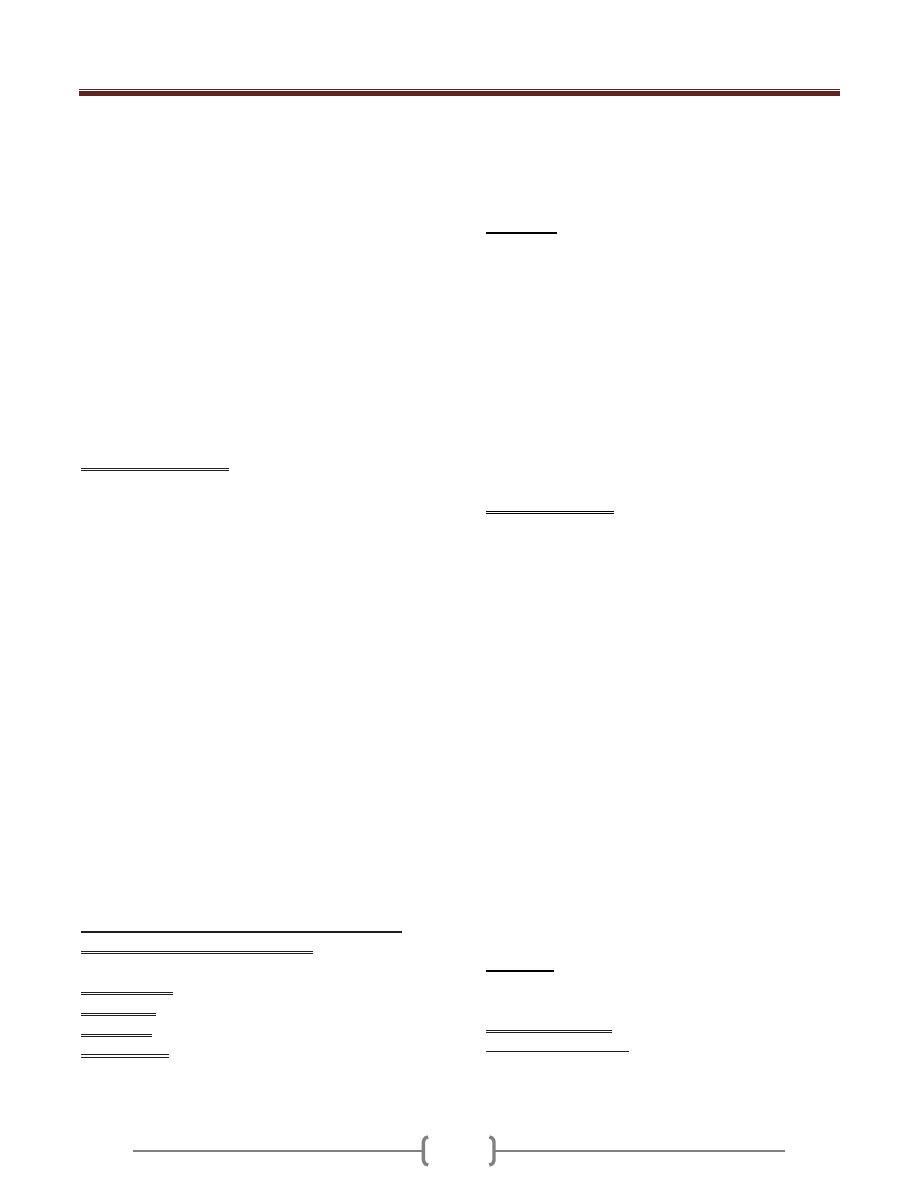

Unit 2: Bacteriology

06

Lecture 1 – General Microbiology

Microbiology in Medicine & Host – Parasite

Relationship

Microbiology: is the study of microorganisms, which are

tiny organisms that live around us & inside our body. An

infection is caused by the infiltration of a disease-causing

microorganism known as a Pathogenic microorganism.

Some pathogenic microorganisms infect humans, but not

other animals & plants. Some pathogenic microorganisms

that infect animals or plants also infect humans. Not all

microorganisms are pathogens. In fact many

microorganisms help to maintain homeostasis in our

bodies and are used in the production of food in our

intestines that assist in the digestion of food & play a

critical role in the formation of vitamins such as vitamin

B & vitamin K. They help by breaking down large

molecules into smaller ones.

The History of Infectious Diseases

The Past

Infectious diseases have been known for thousands of

years, although accurate information on their etiology has

only been available for about a century. In the medical

teachings of Hippocrates, the cause of infections

occurring frequently in a certain locality or during a

certain period (epidemics) was sought in “changes” in the

air according to the theory of miasmas. This concept, still

reflected in terms such as “swamp fever” or “malaria,”

was the predominant academic opinion until the end of

the 19th century, despite the fact that the Dutch cloth

merchant A. van Leeuwenhoek had seen and described

bacteria as early as the 17th century, using a microscope

he built himself with a single convex lens and a very short

focal length. At the time, general acceptance of the notion

of “spontaneous generation”—creation of life from dead

organic material—stood in the way of implicating the

bacteria found in the corpses of infection victims as the

cause of the deadly diseases. It was not until Pasteur

disproved the doctrine of spontaneous generation in the

second half of the 19th century that a new way of thinking

became possible. By the end of that century,

microorganisms had been identified as the causal agents

in many familiar diseases by applying the Henle-Koch

postulates formulated by R. Koch in 1890.

The Henle–Koch Postulates

The postulates can be freely formulated as follows:

The microorganism must be found under conditions

corresponding to the pathological changes and clinical

course of the disease in question.

It must be possible to cause an identical (human) or

similar (animal) disease with pure cultures of the

pathogen.

The pathogen must not occur within the framework of

other diseases as an “accidental parasite.”

These postulates are still used today to confirm the cause

of an infectious disease.

However, the fact that these conditions are not met does

not necessarily exclude a contribution to disease etiology

by a pathogen found in context. In particular, many

infections caused by subcellular entities do not fulfill the

postulates in their classic form.

The Present

The frequency and deadliness of infectious diseases

throughout thousands of years of human history have kept

them at the focus of medical science. The development of

effective preventive and therapeutic measures in recent

decades has diminished, and sometimes eliminated

entirely, the grim epidemics of smallpox, plague, spotted

fever, diphtheria, and other such contagions. Today we

have specific drug treatments for many infectious

diseases. As a result of these developments, the attention

of medical researchers was diverted to other fields: it

seemed we had tamed the infectious diseases. Recent

years have proved this assumption false. Previously

unknown pathogens causing new diseases are being found

and familiar organisms have demonstrated an ability to

evolve new forms and reassert themselves. The origins of

this reversal are many and complex: human behavior has

changed, particularly in terms of mobility and nutrition.

Further contributory factors were the introduction of

invasive and aggressive medical therapies, neglect of

established methods of infection control and, of course,

the ability of pathogens to make full use of their specific

genetic variability to adapt to changing conditions.The

upshot is that physicians in particular, as well as other

medical professionals and staff, urgently require a basic

knowledge of the pathogens involved and the genesis of

infectious diseases if they are to respond effectively to

this dynamism in the field of infectiology. The aim of this

textbook is to impart these essentials to them.

Unit 2: Bacteriology

06

Pathogens: Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic

Microorganisms

According to a proposal by Woese that has been gaining

general acceptance inrecent years, the world of living

things is classified in the three domains: bacteria,

archaea, and eucarya. In this system, each domain is

subdivided into

kingdoms. Pathogenic microorganisms

are found in the domains bacteria and eucarya.

Bacteria. This domain includes the kingdom of the

heterotrophic eubacteria and includes all human pathogen

bacteria. The other kingdoms, for instance that of the

photosynthetic cyanobacteria, are not pathogenic. It is

estimated that bacterial species on Earth number in the

hundreds of thousands, of which only about 5500 have

been discovered and described in detail.

Archaea. This domain includes forms that live under

extreme environmental conditions, including thermophilic,

hyperthermophilic, halophilic,and methanogenic

microorganisms. The earlier term for the archaea was

archaebacteria (ancient bacteria) , and they are indeed a

kind of living fossil. Thermophilic archaea thrive mainly in

warm, moist biotopes such as the hot springs at the top of

geothermal vents. The hyperthermophilic archaea, a more

recent discovery, live near deep-sea volcanic plumes at

temperatures exceeding 100 °C.

Eucarya. This domain includes all life forms with cells

possessing a genuine nucleus.The plant and animal

kingdoms (animales and plantales) are all eukaryotic life

forms. Pathogenic eukaryotic microorganisms include

fungal and protozoan species.

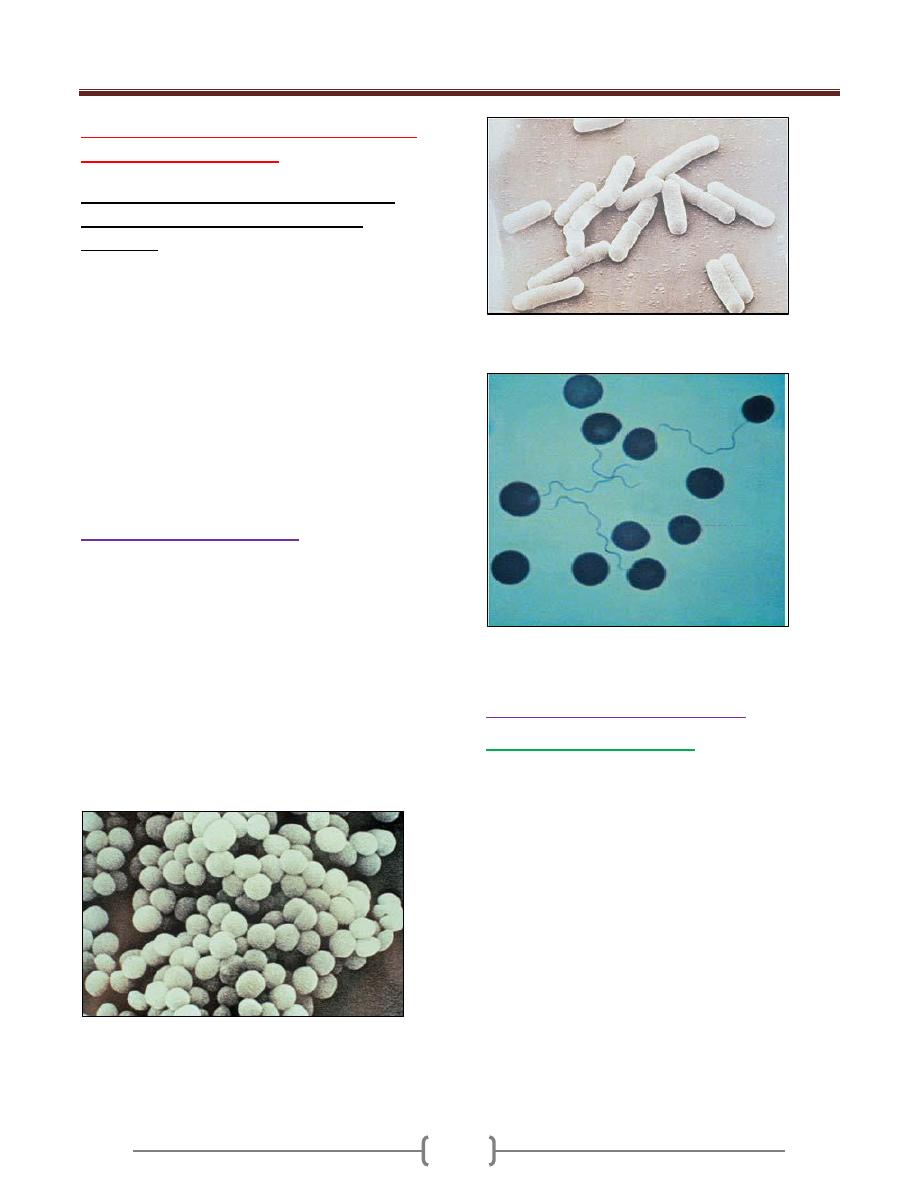

Classic bacteria.

These organisms reproduce asexually by binary transverse

fission. They do not possess the nucleus typical of

eucarya. The cell walls of these organisms are rigid (with

some exceptions, e.g., the mycoplasma).

Chlamydiae. These organisms are obligate intracellular

parasites that are able to reproduce in certain human cells

only and are found in two stages: the infectious,

nonreproductive particles called elementary bodies (0.3

µm) and the noninfectious, intracytoplasmic, reproductive

forms known as initial (or reticulate) bodies (1 µm).

Rickettsiae. These organisms are obligate intracellular

parasites, rod-shaped to coccoid, that reproduce by binary

transverse fission. The diameter of the individual cell is

from 0.3–1 µm.

Mycoplasmas. Mycoplasmas are bacteria without rigid

cellwalls. They are found in a wide variety of forms, the

most common being the coccoid cell (0.3–0.8

µ

m).

Threadlike forms also occur in various lengths.

Fungi and Protozoa

Fungi. Fungi (Mycophyta) are nonmotile eukaryotes with

rigid cell walls and a classic cell nucleus. They contain no

photosynthetic pigments and are carbon heterotrophic,

that is, they utilize various organic nutrient substrates (in

contrast to carbon autotrophic plants). Of more than 50

000 fungal species, only about 300 are known to be

human pathogens. Most fungal infections occur as a result

of weakened host immune defenses.

Protozoa. Protozoa are microorganisms in various sizes

and forms that may be free-living or parasitic. They

possess a nucleus containing chromosomes and organelles

such as mitochondria (lacking in some cases), an en-

doplasmic reticulum, pseudopods, flagella, cilia,

kinetoplasts, etc. Many parasitic protozoa are transmitted

by arthropods, whereby multiplication and transformation

into the infectious stage take place in the vector.

Animals

Helminths. Parasitic worms belong to the animal

kingdom. These are metazoan organisms with highly

differentiated structures. Medically significant groups

include the trematodes (flukes or flatworms), cestodes

(tapeworms), and nematodes (roundworms).

Subcellular Infectious Entities

Prions (proteinaceous infectious particles). The evidence

indicates that prions are protein molecules that cause

degenerative central nervous system (CNS) diseases such

as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, kuru, scrapie in sheep, and

bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) (general term:

transmissible spongiform encephalopathies [TSE]).

Viruses. Ultramicroscopic, obligate intracellular parasites

that:

contain only one type of nucleic acid, either DNA or RNA

possess no enzymatic energy-producing system and no

protein-synthesizing apparatus, and

Force infected host cells to synthesize virus particles.

Arthropods. These animals are characterized by an external

chitin skeleton, segmented bodies, jointed legs, special

mouthparts, and other specific features. Their role as direct

causative agents of diseases is a minor one (mites, for

instance, cause scabies) as compared to their role as vectors

transmitting viruses, bacteria, protozoa , & helminths.

Unit 2: Bacteriology

06

Basic Terminology of Infectiology

The terms pathogenicity and virulence are not clearly

defined in their relevance to microorganisms. They are

sometimes even used synonymously. It has been proposed

that pathogenicity be used to characterize a particular

species and that virulence be used to describe the sum of

the disease-causing properties of a population (strain) of a

pathogenic species.

Pathogenicity and virulence in the microorganism

correspond to susceptibility in a host species and

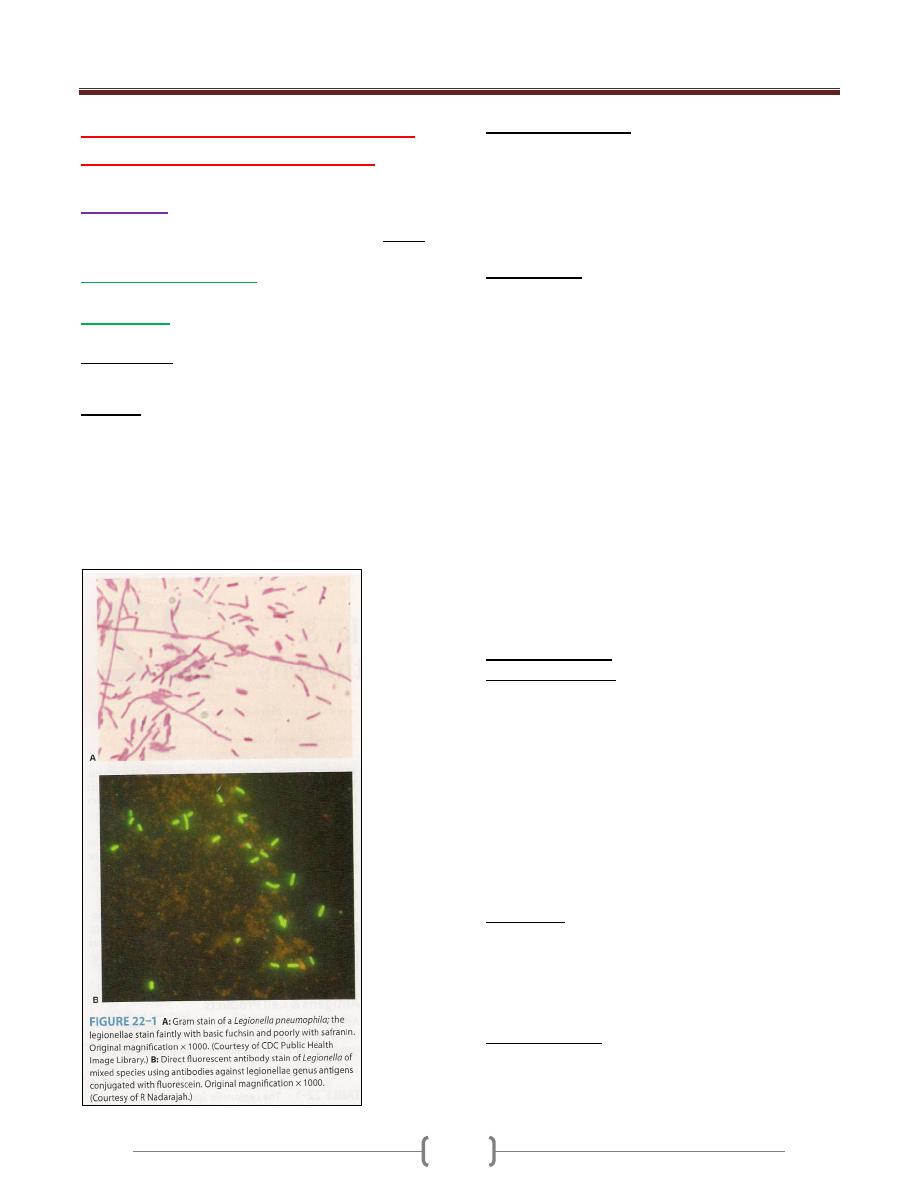

disposition in a specific host organism, whereby an