0

Mustafa Hatim Kadhim

Baghdad University

Al-kindy college of medicine

Third Stage

2013 - 2014

1

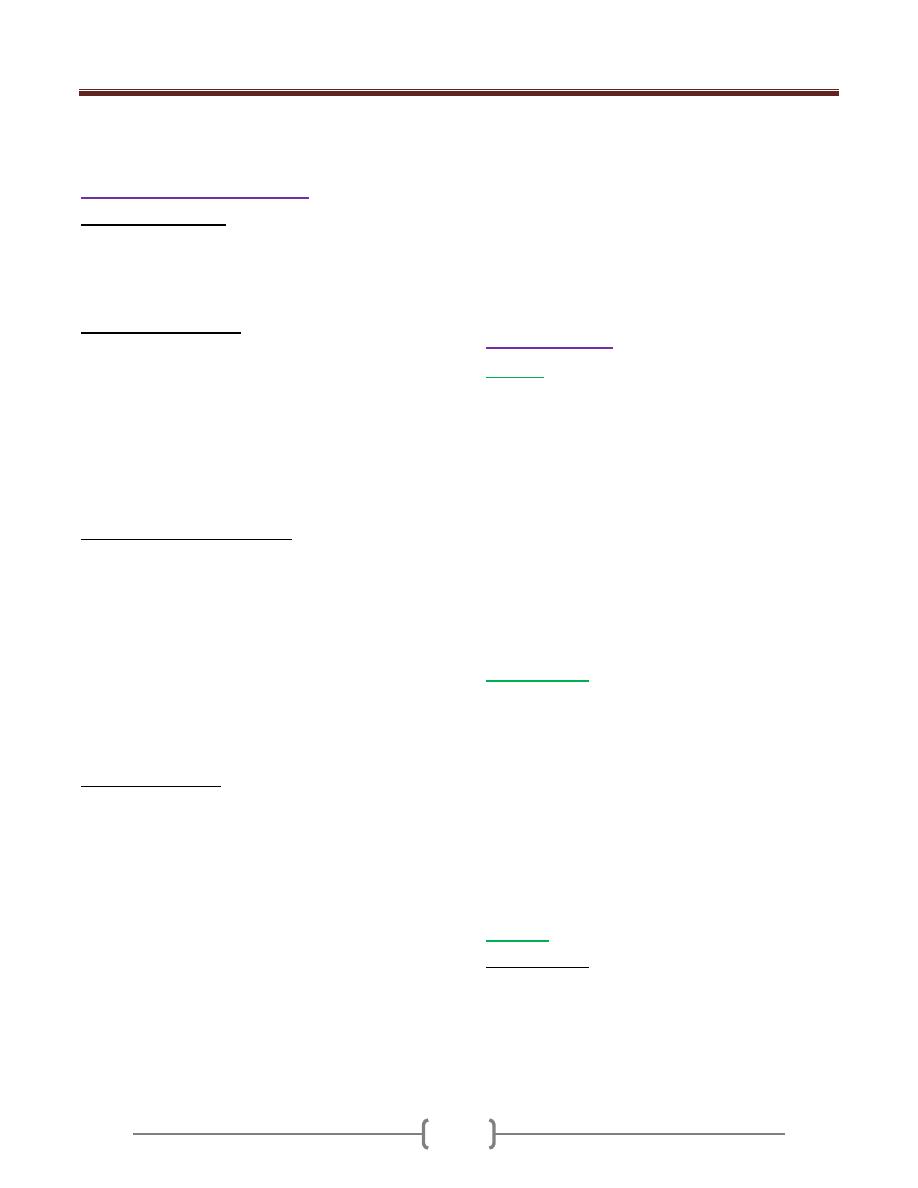

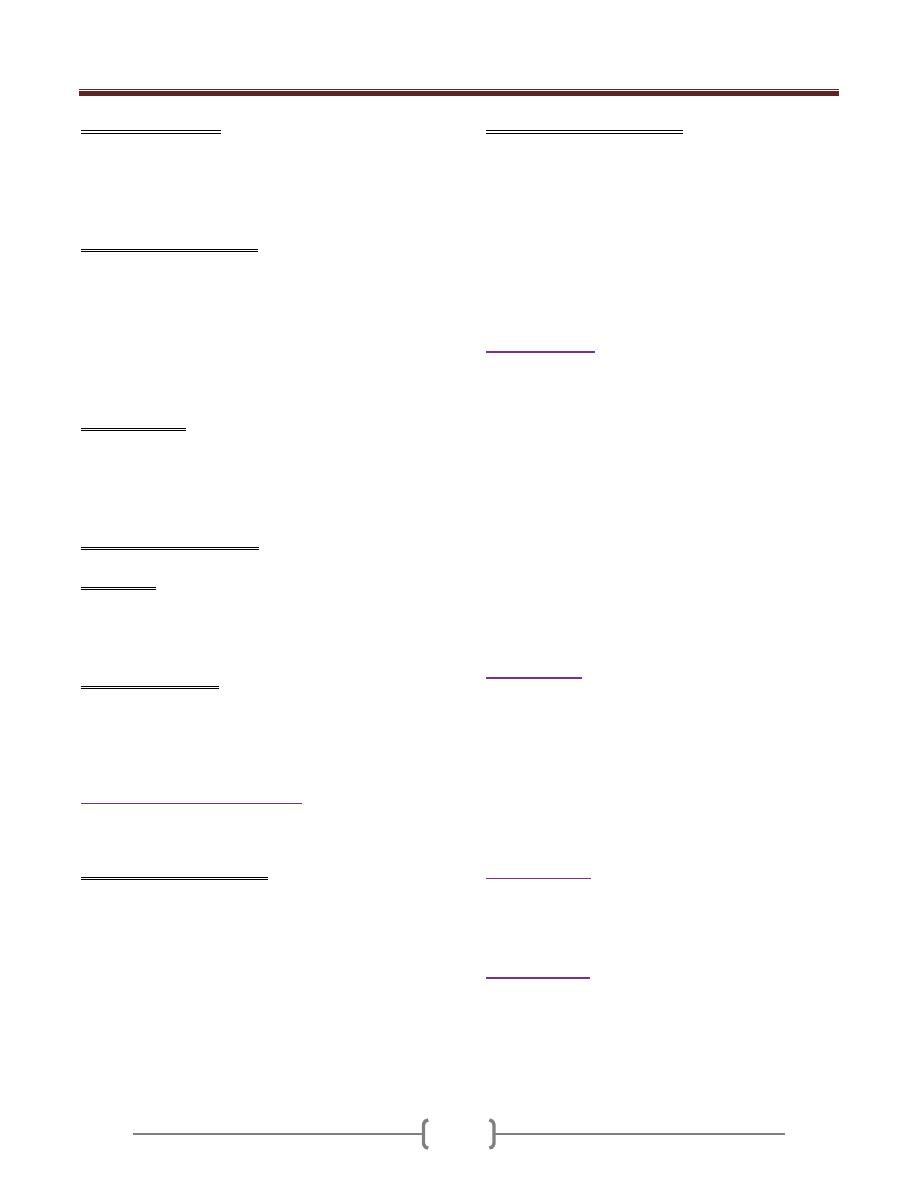

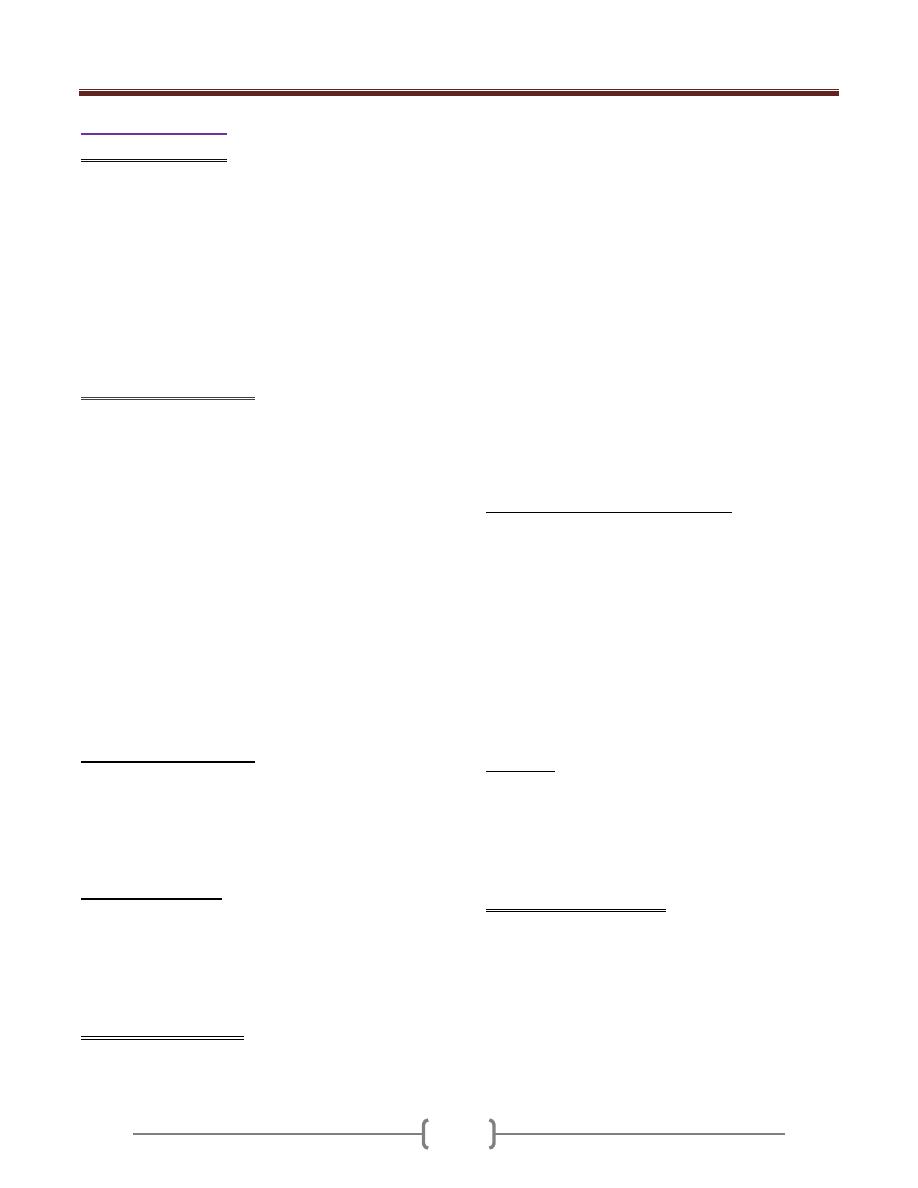

List of contents

الفصل االول

Lecture

number

Lecture name

Doctor name

Page

number

1

Introduction

دكتور زهير

3-6

2

The body response to trauma

دكتور

ليث نايف

7-11

3+4

Wounds, tissue repair and scars

دكتور

عماد

12-19

5+6

Hemorrhage & Shock

دكتور

عبد الهادي

20-23

7

Blood Transfusion

دكتور

توفيق

24-30

8+9

Fluid electrolytes & Acid-Base

balance

دكتور

رائد

31-48

10+11

Operating Room Sterilization

& Sterile precautions

دكتور

حميد

49-51

12+13

Burn

دكتور

احمد كمال

52-55

الفصل الثاني

Lecture

number

Lecture name

Doctor name

Page

number

1

Wound infection

دكتور

ممتاز

57-58

2+3

Cyst, Ulcer, sinuses & Fistulas

دكتور

ابتسام

59-62

4+5+6

Oncology

دكتور زهير

63-66

7+8

Artificial nutritional support

دكتور

ليث نايف

67-75

9

Vascular Surgery

دكتور

مثنى

العسل

77-78

2

Lecture 1 - Introduction to Surgery

3

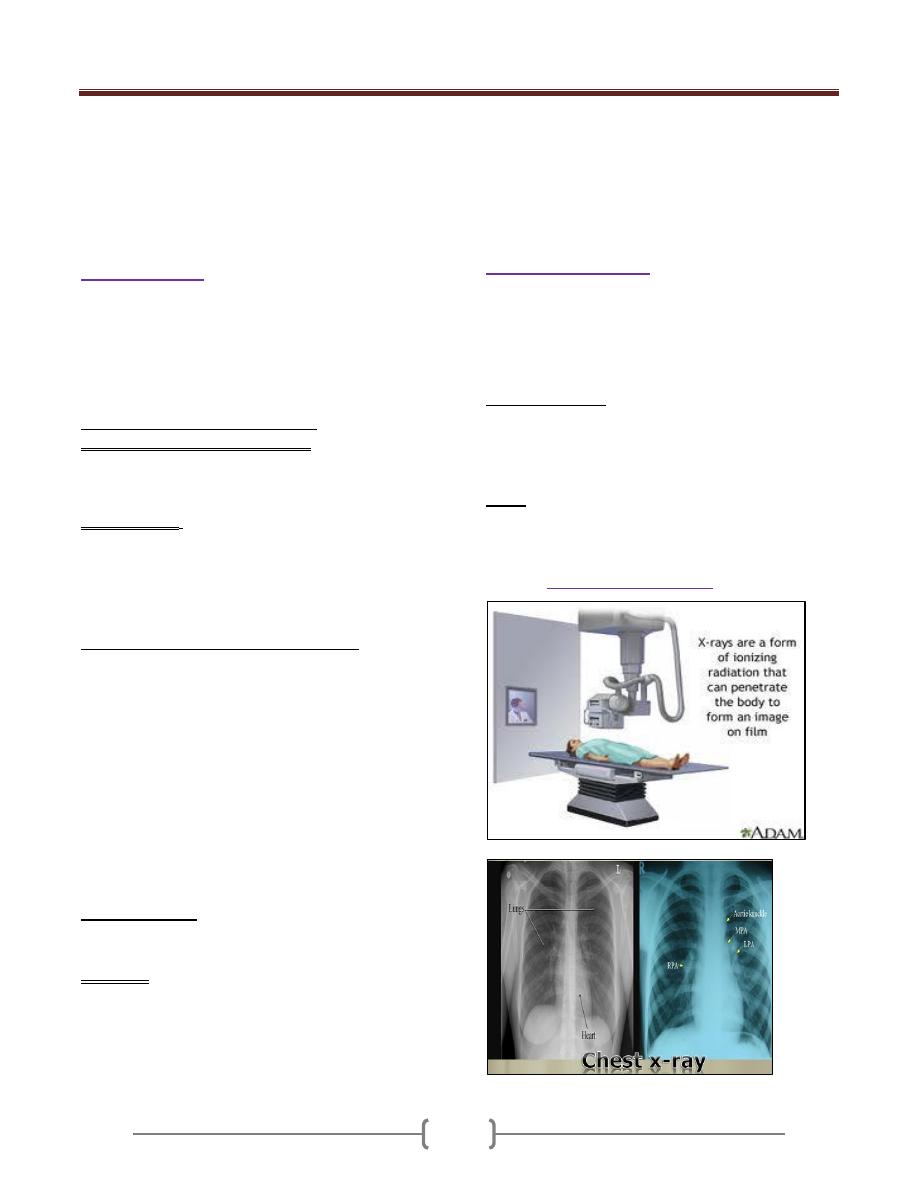

Surgical diagnosis depends on: Sound knowledge of:

Anatomy

Physiology

Pathology

Specific history & clinical examination

Radiology

Surgical history

History of the chief complaint is the key step in surgical

diagnosis.

There is no standard surgical history of each disease as

the disease may present with certain symptoms and the

other patient present with the other or part of it as their

symptoms may take time to appear or never appear.

There are 2 types of surgical history:

1) Outpatient or emergency room history; Specific complaint

of the patient is pinpointed.

Objective: is to obtain diagnosis on which treatment is

ordered.

2) Clerking history: is the history of the patients who was

admitted for an elective surgery.

Objective: is to assess that the treatment planned is

correctly indicated & to ensure that the patient is suitable

for that operation

Outpatient or emergency room history:

You may ask

When the symptom started.

How it has progressed.

Whether there are any associated symptoms.

Whether the symptoms are improving or getting worse.

What relieve & what aggravate the symptoms.

What were the effects of the drugs which were taken.

History of previous illnesses, concurrent illnesses.

Drug therapy.

Allergies.

Complications related to anesthesia.

Clerking history

The clerking history centers on direct questioning of the

patient about specific points related to the complaint.

Examples:

1) Ask about signs of prostatism in patients with benign

prostatic hypertrophy to compare them with postoperative

state to assess the effect of the surgical procedure.

2) In a patient who was referred by a physician :

Ask about the indications for surgery.

The surgeon's decision whether or not the patient will

benefit from the operation.

These are particularly important in patients with non-

malignant condition where continued medical

treatment is an option.

Clinical Examination

Examine the whole patient particularly before operation.

The examination should be as thorough as in a routine

medical examination.

In examining a specific surgical structure one should

follow an accurate clinical description for example in :

Diagnosis of lump:

1) Site, size, shape, surface, consistency , mobility.

2) Important physical signs these includes:

Thrill, sign of compression, sign of indentation, sign of

aneurysm (pulsatile masses).

Ulcer:

Site, size, shape, floor, base, edge &surrounding tissues.

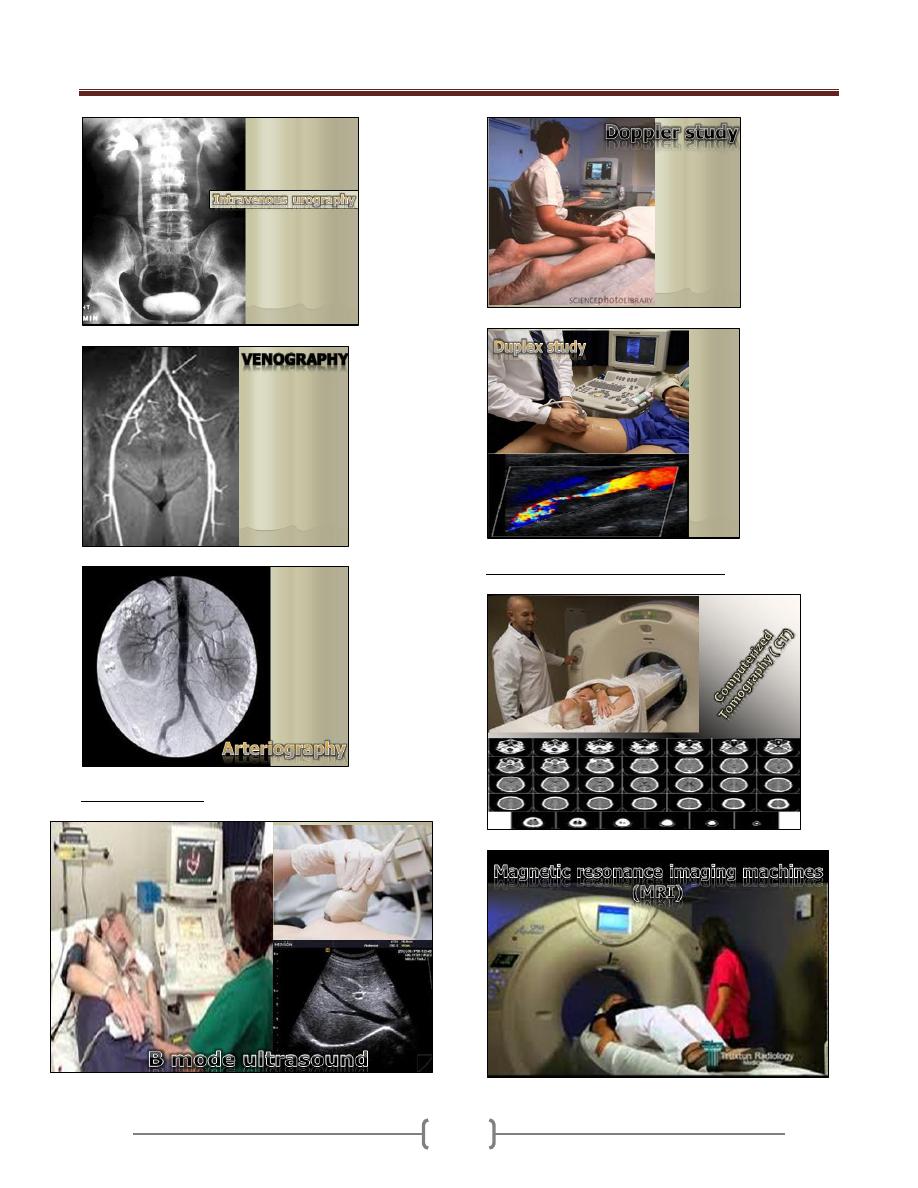

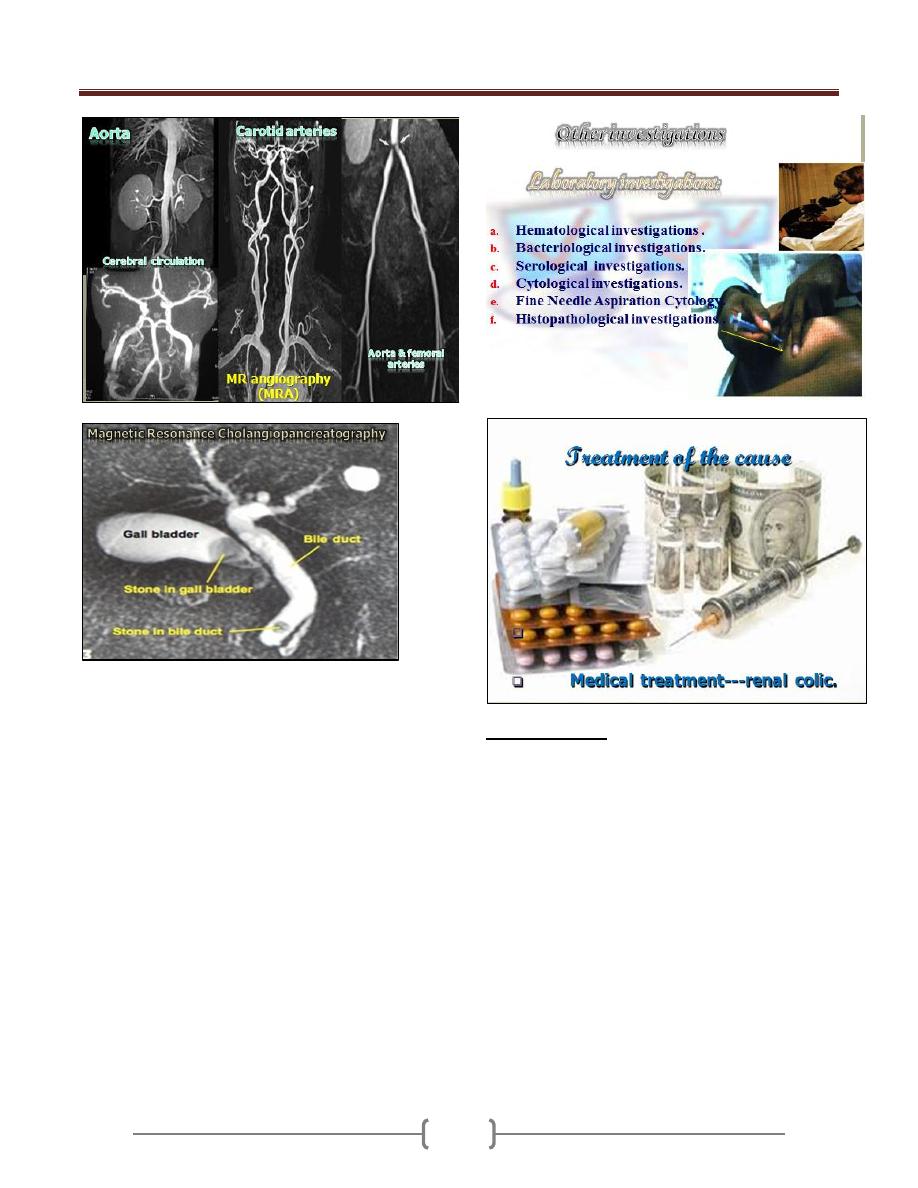

Confirmation of the diagnosis could be done by:

(Diagnostic

Radiology or imaging

)

Lecture 1 - Introduction to Surgery

4

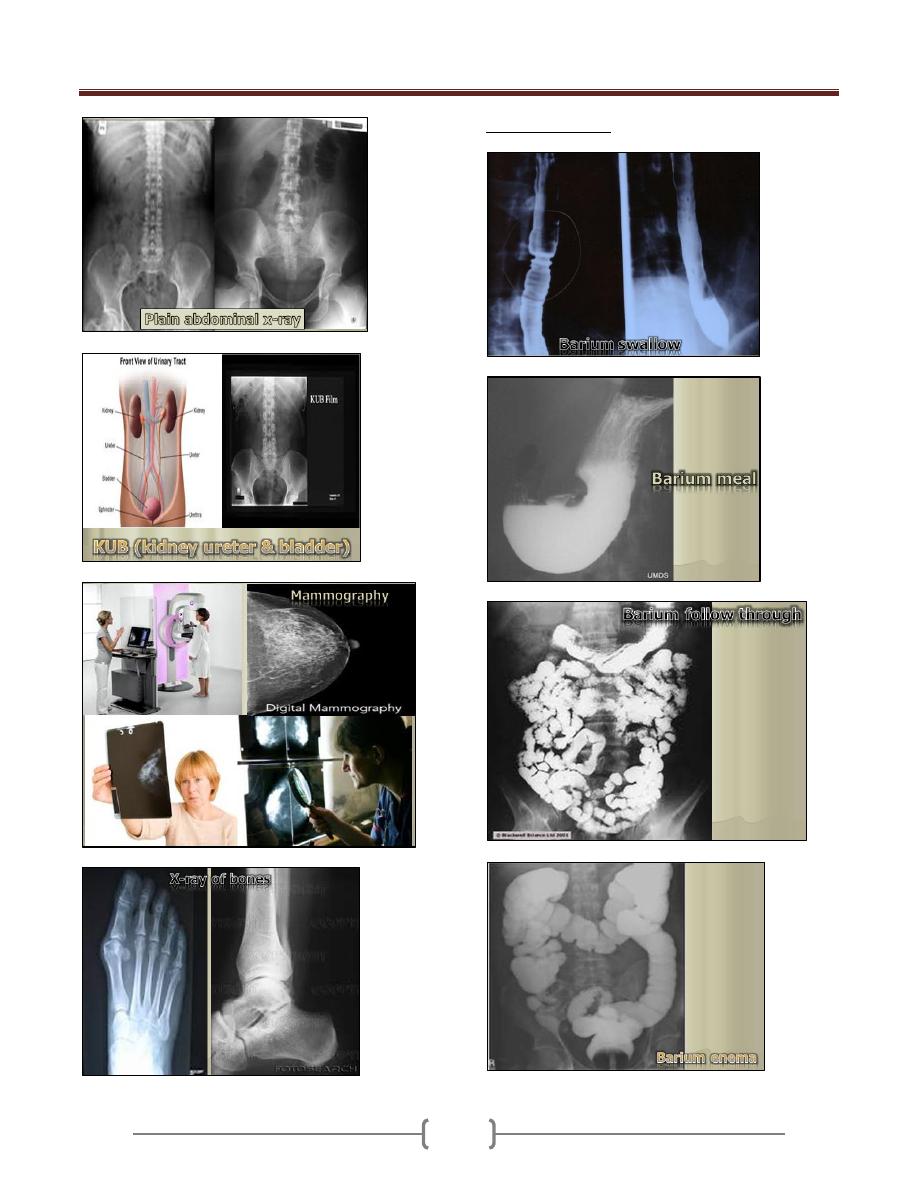

B. Contrast Studies

Lecture 1 - Introduction to Surgery

5

Ultrasound Studies

Advanced Radiological investigations

Lecture 1 - Introduction to Surgery

6

Surgical treatment

Appendectomy

Cholecystectomy

Drainag e of an abscess

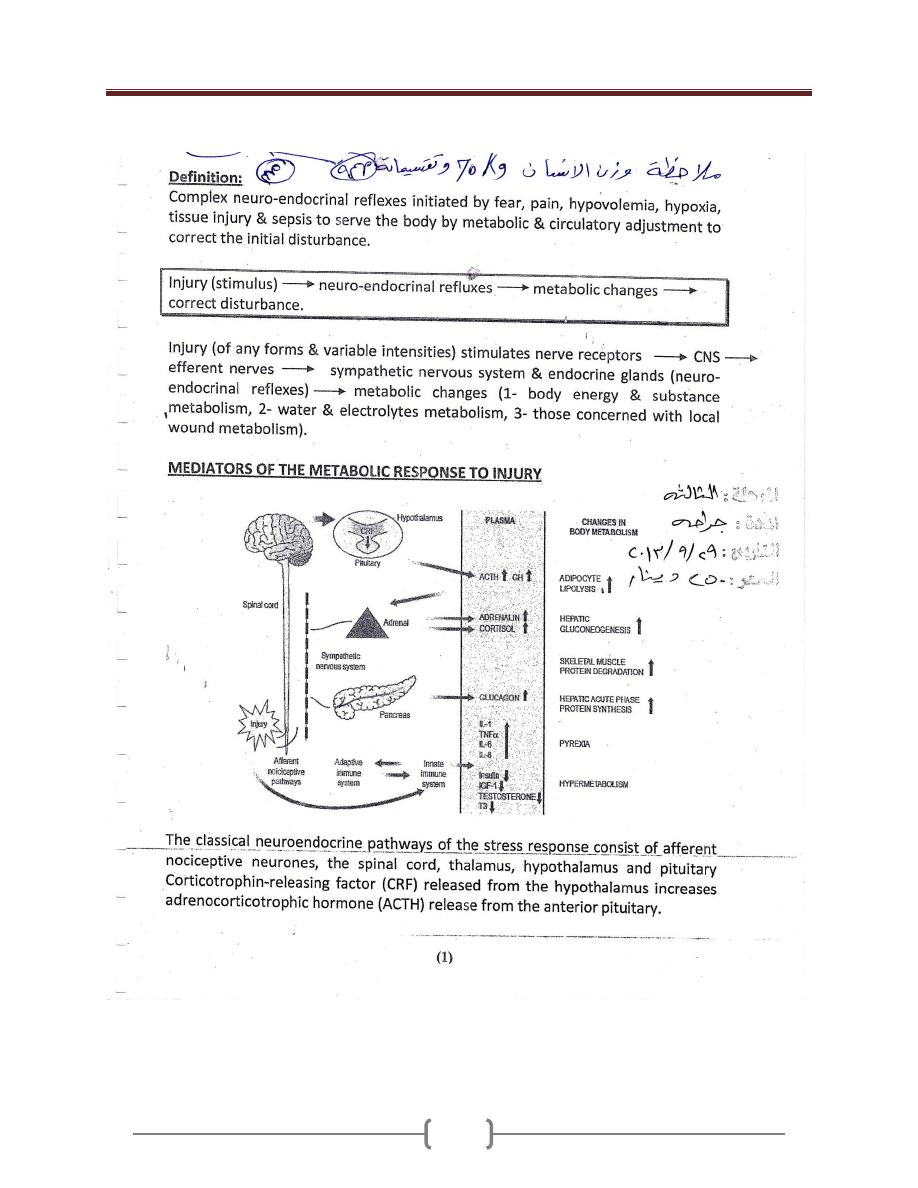

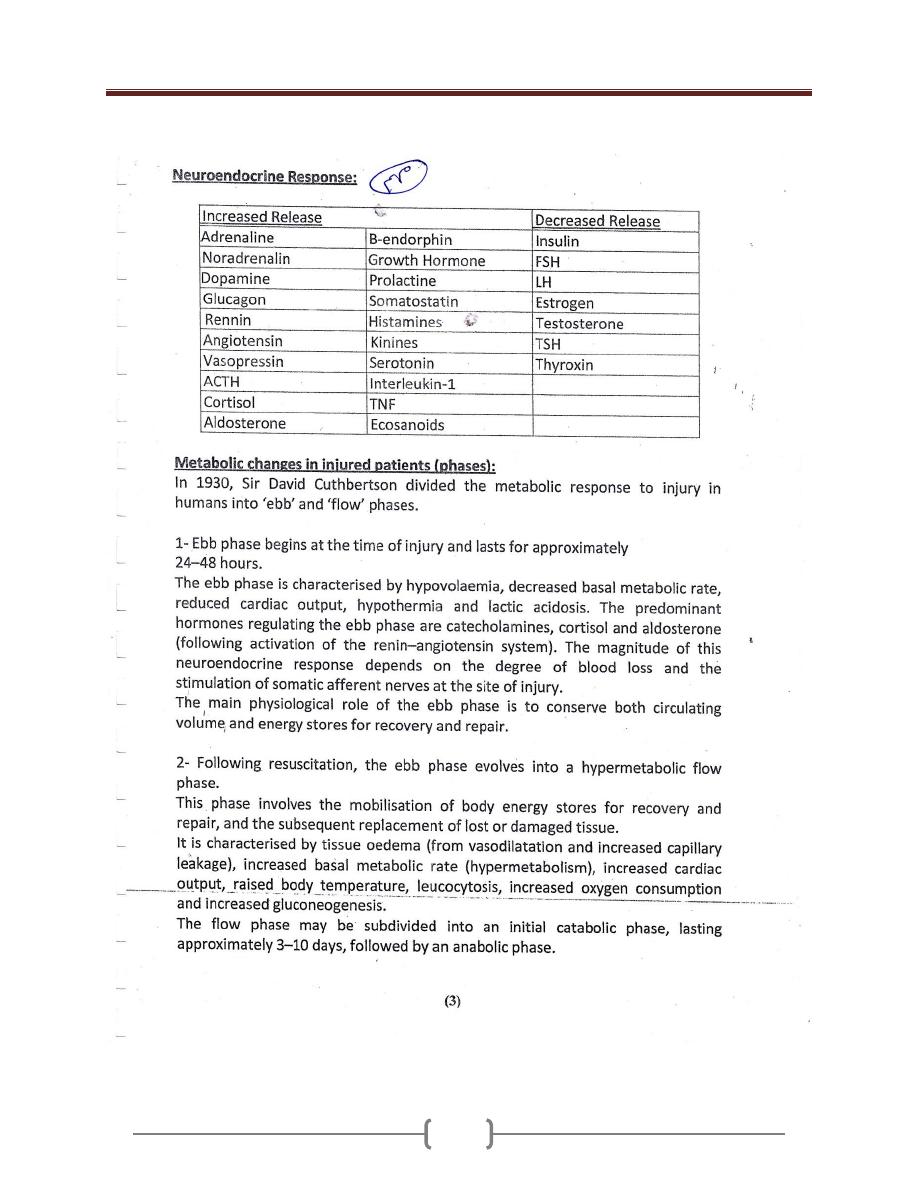

Lecture 2 – Body Response to trauma

7

Lecture 2 – Body Response to trauma

8

Lecture 2 – Body Response to trauma

9

Lecture 2 – Body Response to trauma

10

Lecture 2 – Body Response to trauma

11

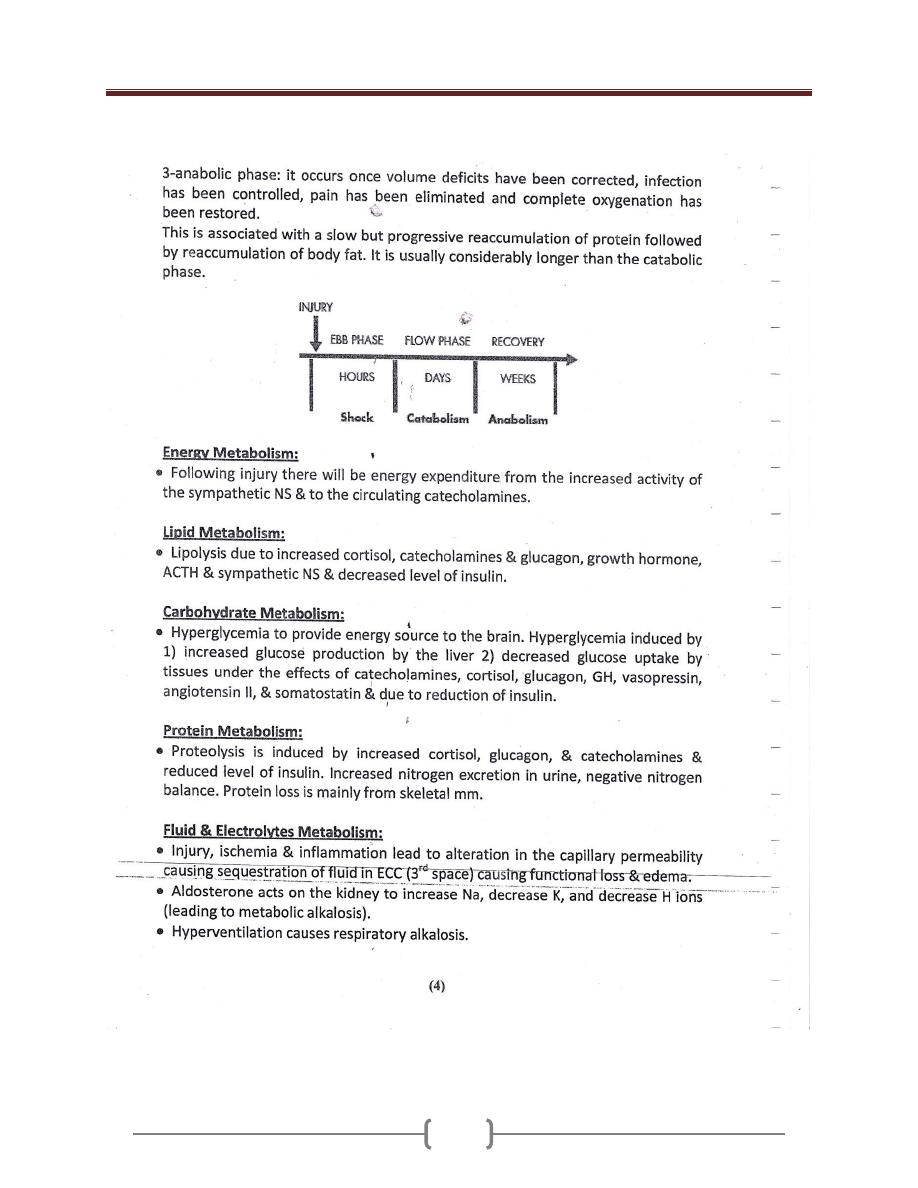

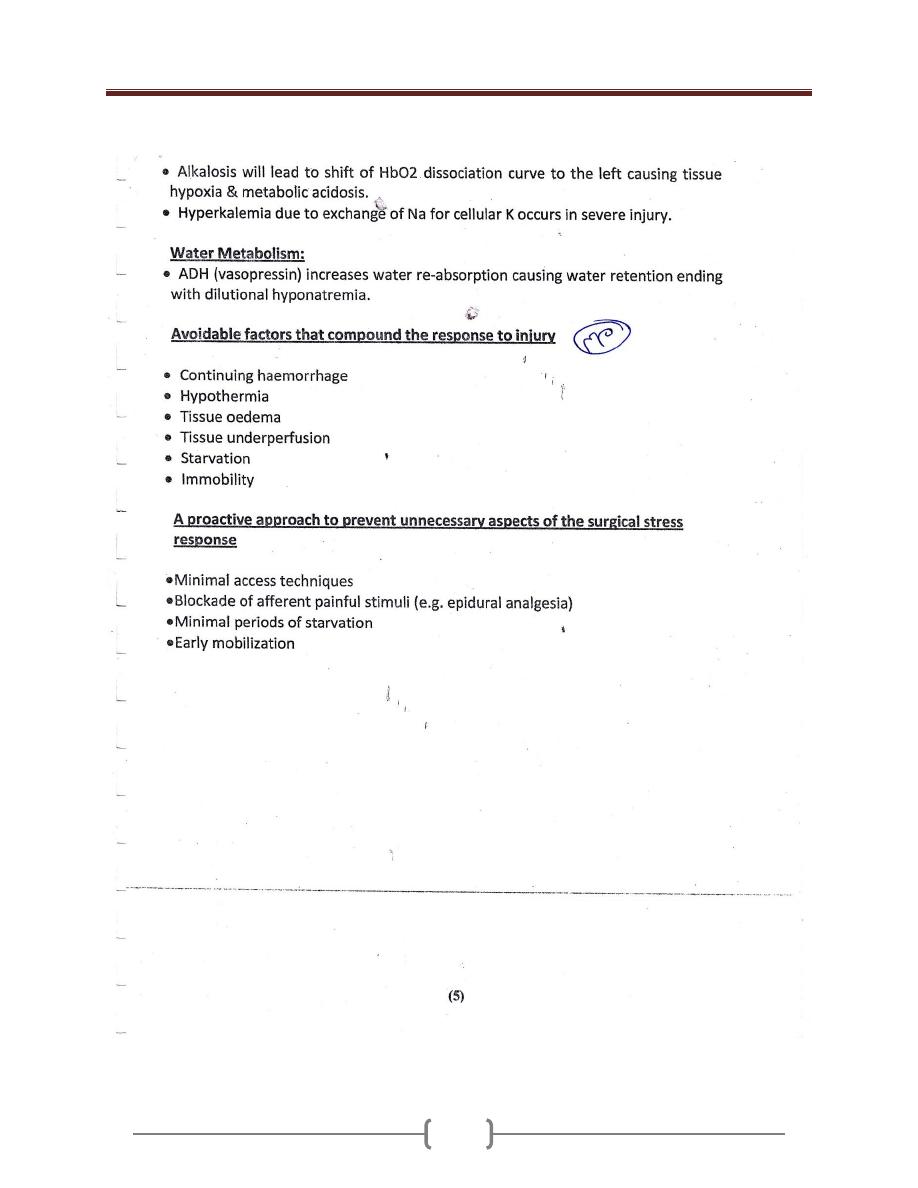

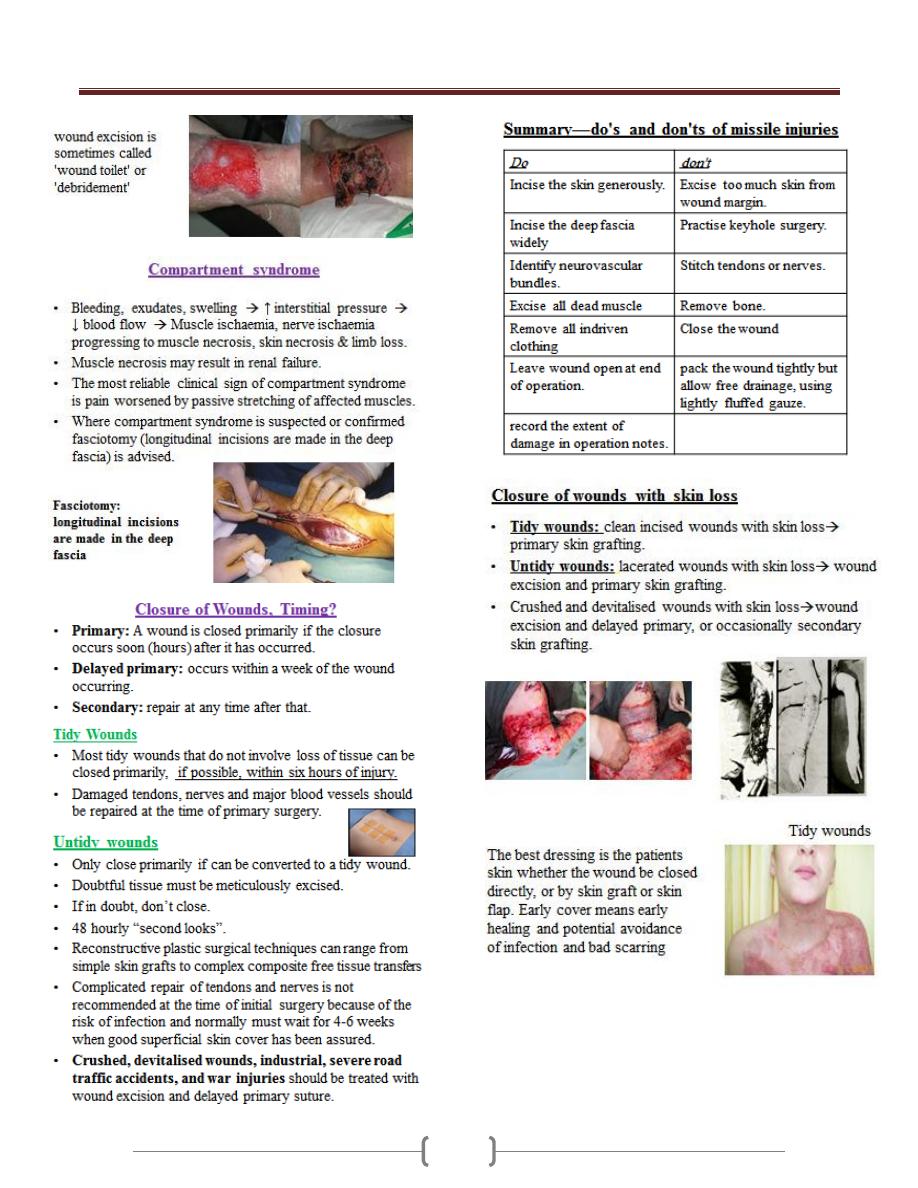

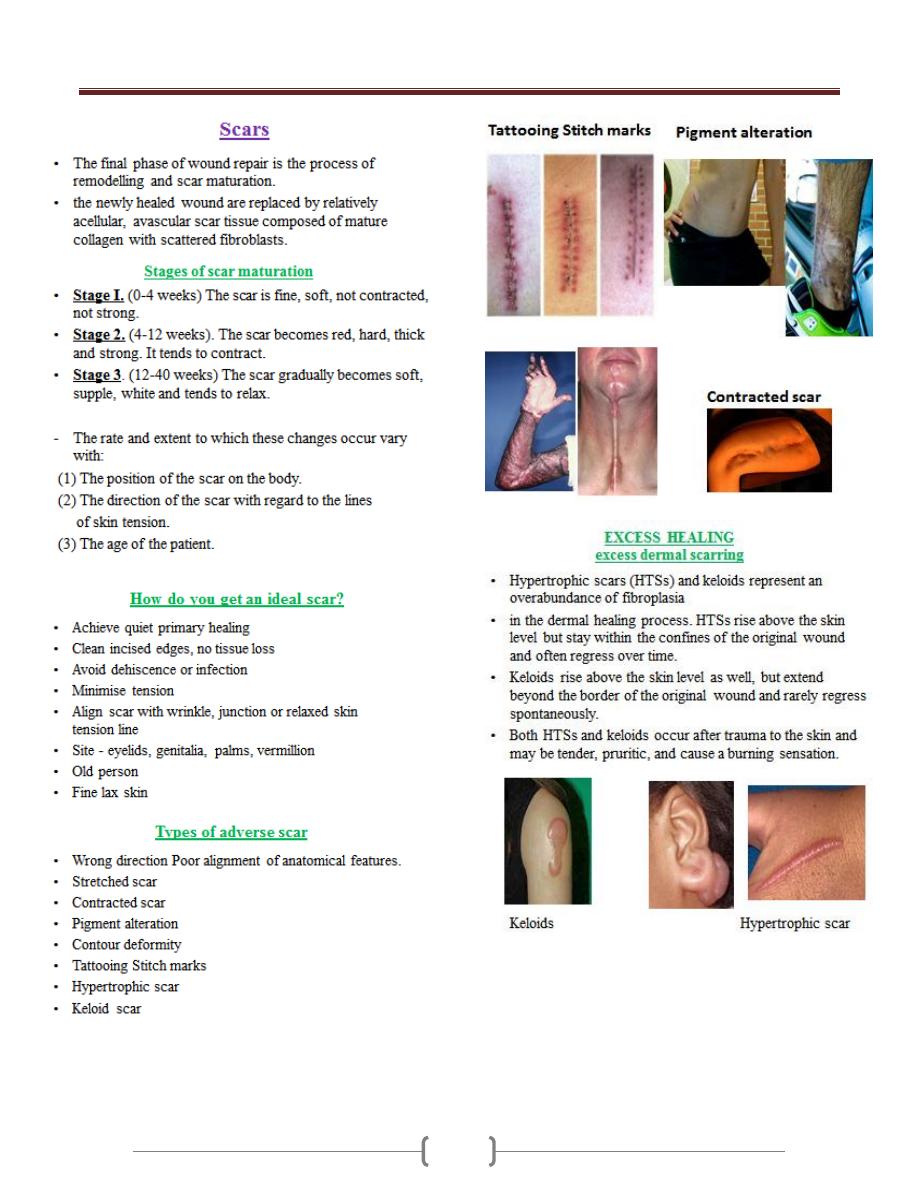

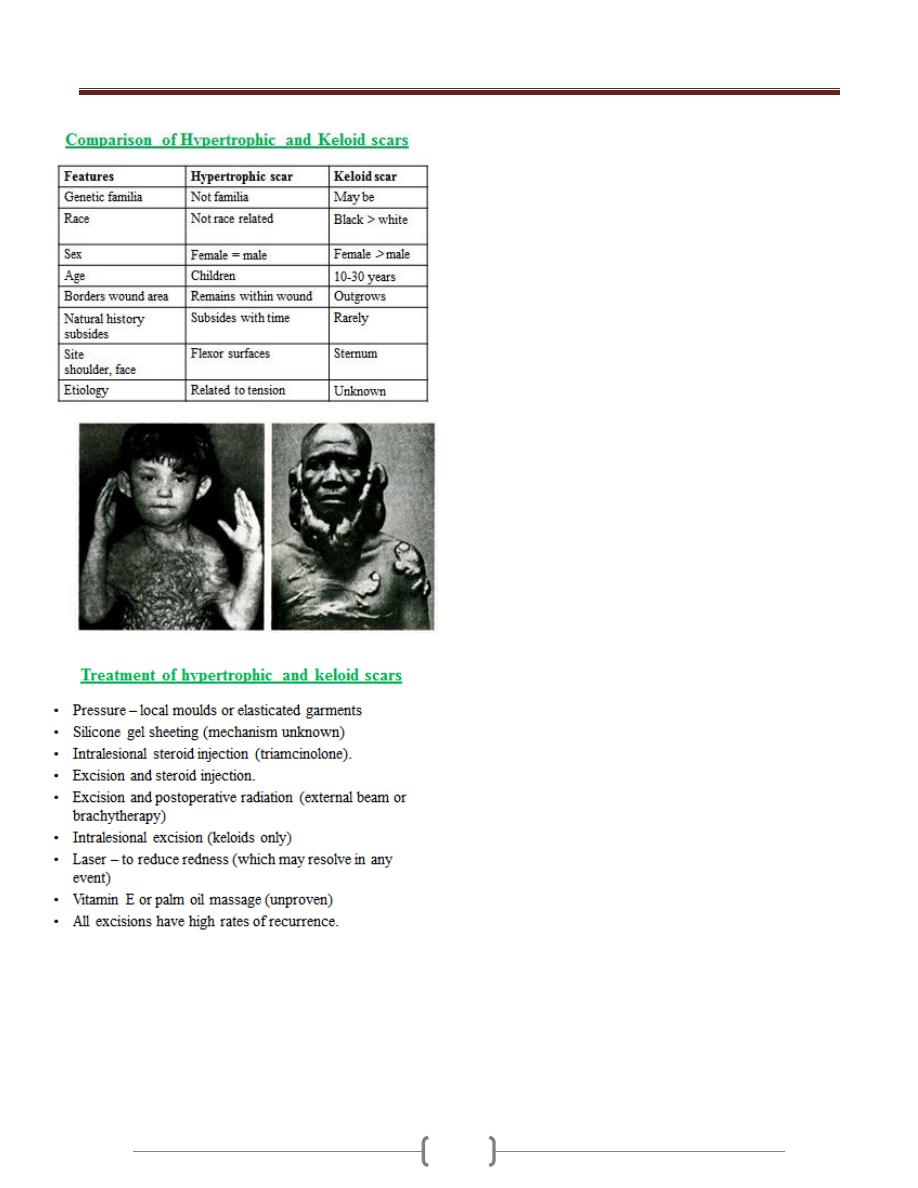

Lecture 3+4 - Wounds, tissue repair and scars

12

Lecture 3+4 - Wounds, tissue repair and scars

13

Lecture 3+4 - Wounds, tissue repair and scars

14

Lecture 3+4 - Wounds, tissue repair and scars

15

Lecture 3+4 - Wounds, tissue repair and scars

16

Lecture 3+4 - Wounds, tissue repair and scars

17

Lecture 3+4 - Wounds, tissue repair and scars

18

Lecture 3+4 - Wounds, tissue repair and scars

19

Lecture 5+6 – Hemorrhage & Shock

20

Hemorrhage

Haemorrhage or bleeding is the loss of blood from the

circulatory system. It must be recognized & managed

aggressively to avoid multiple organ failure & death. It

must be treated first by arresting it, then other measures

like fluid resuscitation & blood transfusion.

Pathophysiology

Haemorrhage may lead to hypovolaemic shock

(hypoperfusion), the following events may occur:

Cellular anaerobic metabolism with lactic acidosis

(this acidosis causes coagulopathy & further

haemorrhage).

Ischaemic endothelial cells activate anti-coagulant

pathways & further haemorrhage.

Underperfused muscles are unable to generate heat so

hypothermia results which affects coagulation &

results in further haemorrhage.

These events result in a vicious cycle leading to

physiological exhaustion & death.

Medical therapy has a tendency to worsen the conditio

Intravenous fluids & blood are cold, so causes

hypothermia.

Many crystalloid fluids are acidic (normal saline has a

PH of 6.7).

Surgery causes heat loss (by opening body cavities) &

causes further haemorrhage.

Types of haemorrhage

1) Revealed & concealed haemorrhage :

Revealed haemorrhage: Obvious external haemorrhage.

eg. bleeding from open arterial wound, haematemesis

from DU.

Concealed haemorrhage: It is contained within body

cavity. It must be diagnosed & treated early, eg.

Abdominal (peritoneal & retroperitoneal), thoracic, &

pelvic bleeding due to trauma. Non-traumatic cause eg.

ruptured aortic aneurysm, occult GI bleeding.

2) Primary, reactionary, & secondary haemorrhage:

Primary hemorrhage: Occurring immediately as a result

of injury or surgery.

Reactionary (Delayed) haemorrhage : Occurring within

24 hours. Usually caused by dislodgement of clot (by

resuscitation, vasodilatation, normalization of BP) or due

to a slippage of a ligature.

Secondary haemorrhage: It usually occurs within 7 – 14

days after injury. It is precipitated by infection, pressure

necrosis (such as from a drain), or malignancy.

3) Surgical & non-surgical haemorrhage

Surgical haemorrhage: Result from direct injury; it is

amenable to surgical control.

Non-surgical haemorrhage: Result from oozing from

raw surfaces due to coagulopathy. It requires correction of

coagulation abnormalities or packing.

Hemorrhag is broken down into 4 classes by the

American College of Surgeons' Advanced Trauma Life

Support

1) Class I Hemorrhage involves up to 15% of blood

volume. There is typically no change in vital signs and

fluid resuscitation is not usually necessary.

2) Class II Hemorrhage involves 15-30% of total blood

volume. A patient is often tachycardic (rapid heartbeat)

with a narrowing of the difference between the systolic

and diastolic blood pressures. The body attempts to

compensate with peripheral vasoconstriction. Skin may

start to look pale and be cool to the touch. Volume

resuscitation with crystalloids (Saline solution or Lactated

Ringer's solution) is all that is typically required. Blood

transfusion is not typically required.

3) Class III Hemorrhage involves loss of 30-40% of

circulating blood volume. The patient's blood pressure

drops, the heart rate increases, peripheral perfusion, such

as capillary refill worsens, and the mental status worsens.

Fluid resuscitation with crystalloid and blood transfusion

are usually necessary.

4) Class IV Hemorrhage involves loss of >40% of

circulating blood volume. The limit of the body's

compensation is reached and aggressive resuscitation is

required to prevent death

Lecture 5+6 – Hemorrhage & Shock

21

Management of haemorrhage

1) Identify haemorrhage: Revealed haemorrhage may be

obvious but the diagnosis of concealed haemorrhage may

be difficult. Any shock should be assumed to be

hypovolaemic until proved otherwise & the cause should

be assumed haemorrhage until this has been excluded.

2) Immediate resuscitation:

Direct pressure should be placed over the site of external

haemorrhage .

Airway & breathing should be assessed & controlled.

Large- bore intravenous access should be instituted &

blood drawn for cross- matching.

Intravenous fluids should be given, & when the blood is

available it should be given according to the degree of

haemorrhage.

3) Identify the site of haemorrhage:

This is important to define the next step in haemorrhage

control (operation, endoscopic control,

angioembolization).

• History: Previous episodes, known aneurysm, drugs

(steroidal & nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory).

• Physical examination: Nature of blood : fresh, melaena,

external signs of injury, abdominal tenderness.

• Investigations: Must be appropriate to the patients

physiological condition, & unnecessary investigations

must be avoided. Chest & pelvic radiography, abdominal

ultrasound, diagnostic peritoneal aspiration.

4) haemorrhage control:

Control must be achieved rapidly by moving the patient

rapidly to a place of haemorrhage control (theater,

angiography or endoscopy suites). Patient needs

lifesaving procedure so surgery may need to be limited to

the minimum necessary to stop bleeding & control sepsis.

More definitive repairs can be delayed until the patient is

physiologically capable of sustaining the procedure

(Damage control surgery).

Shock

Shock is the most important cause of death among

surgical patients.

Definition: It is a systemic state of low tissue perfusion,

which is inadequate for normal cellular respiration.

Pathophysiology

1) Cellular

Tissue perfusion is reduced,

cells are deprived of oxygen

anaerobic metabolism occurs

Liberation of lactic acid (instead of carbon dioxide)

causes systemic metabolic acidosis .

As glucose within the cells exhausted anaerobic

respiration ceases

failure of sodium potassium pump in the cell membrane

& intracellular organelles.

Intracellular lysosomes release autodigestive enzymes &

cell lysis ensues.

Intracellular contents including potassium are released

into the blood stream causing hyperkalaemia.

2) Microvascular

Tissue ischemia activate immune & coagulation

systems.

Hypoxia & acidosis activate complement & prime

neutrophils resulting in the generation of oxygen free

radicals & cytokine release.

These lead to injury to capillary endothelial cells &

further activation of the immune & coagulation

systems.

The damaged endothelium becomes leaky, so fluid

leaks & tissue oedema ensues, exacerbating cellular

hypoxia.

3) Systemic

a) Cardiovascular: Decreased preload & afterload cause

compensatory baroreceptor response which leads to

increased sympathetic activity & release of

catecholamines into the circulation which results in

tachycardia & systemic vasoconstriction (except in sepsis)

Lecture 5+6 – Hemorrhage & Shock

22

b) Respiratory: The metabolic acidosis & increased

sympathetic activity result in an increased respiratory rate

& minute ventilation to increase the excretion of carbon

dioxide & this produces compensatory respiratory

alkalosis.

c) Renal: Decreased perfusion pressure in the kidney leads

to reduced filtration at the glomerulus & a decreased urine

output.

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis is stimulated

resulting in further vasoconstriction & increased sodium

& water reabsorption by the kidney.

d) Endocrine: Antidiuretic hormon (vasopressin) is released

from hypothalamus & results in vasoconstriction & water

reabsorption in the renal collecting system.

Cortisol is also released from the adrenal cortex causes

sodium & water reabsorption & sensitising the cells to

catecholamines.

4) Ischemia-perfusion syndrome

Systemic hypo-perfusion causes tissue hypoxia which

activates complement, neutrophils, & microvascular

thrombi which cause further endothelial damage to

organs such as the lungs & kidneys.

The acid & potassium load cause myocardial

depression, vascular dilatation & further hypotension.

These events cause multiple organ failure.

Classification of shock

1) Hypovolemic shock:

It is the most common form of shock, caused by reduced

circulating volume due to

a) haemorrhagic causes

b) Non-haemorrhagic causes: poor fluid intake, excessive

fluid loss because of vomiting, diarrhea, urinary loss

(as in diabetes), evaporation & third- spacing (fluid is

lost into GIT & interstitial spaces as in bowel

obstruction or pancreatitis.

2) Cardigenic shock

It is due to primary failure of the heart to pump blood to

the tissues.

It occurs in:

a) myocardial infarction

b) dysrhythmias

c) valvular heart disease

d) blunt myocardial injury

e) cardiomyopathy

f) Myocardial depression: results from endogenous

factors released in sepsis & pancreatitis or exogenous

factors such as drugs.

3) Obstructive shock

Mechanical obstruction of cardiac filling causes reduction

of preload & fall in cardiac output.

It occurs in :

a) cardiac tamponade

b) tension pneumothorax

c) massive pulmonary embolism

d) Air embolism.

4) Distributive shock

There is abnormally high cardiac output with

vasodilatation & hypotension. There is maldistribution of

blood flow at a microvascular level with arteriovenous

shunting & dysfunction of the cellular utilization of

oxygen. The peripheries are worm & capillary refill is

brisk despite profound shock.

It occurs in

a) Septic shock: caused by release of endotoxins &

acivation of cellular & humoral components of the

immune system.

b) Anaphylaxis: vasodilatation is caused by histamine

release.

c) Spinal cord injury (neurogenic shock): caused by

failure of sympathetic outflow & adequate vascular

tone.

5)

Endocrine shock

: It occurs in:

a) hypo- & hyperthyroidism

b) Adrenal insufficiency.

In hypothyroidism there is disordered vascular & cardiac

responsiveness to circulating catecholamines so cardiac

output falls & there may be associated cardiomyopathy.

Hyperthyroidism may cause a high- output cardiac failure.

In adrenal insufficiency there is hypovolaemia & poor

response to circulating & exogenous catecholamines, it

occurs in Addisons disease, & systemic sepsis.

Severity of shock:

1) Compensated shock: There is a compensatory

cardiovascular & endocrine response to maintain adequate

blood flow to the most vital organs (brain, heart, lungs, &

kidneys) & reducing perfusion to the skin, muscles, &

Lecture 5+6 – Hemorrhage & Shock

23

GIT. Apart from tachycardia & cool peripheries

(vasoconstriction) there may be no other clinical signs of

hypovolaemia. Loss of 15% of the circulating blood

volume is within normal compensatory mechanism.

Blood pressure is only falls after 30-40% of circulating

volume has been lost.

2) Decompensation: Further loss of circulating volume

causes progressive cardiovascular, respiratory, & renal

decompensation.

3) Mild shock: Initially there is tachycardia, tachypnoea &

mild reduction in urine output with mild anxiety. Blood

pressure is maintained although there is a decrease in

pulse pressure. The peripheries are cold & sweaty with

prolonged capillary refill times (except in septic

distributive shock).

4) Moderate shock: As shock progresses, renal

compensatory mechanisms fail, renal perfusion falls &

urine output decreases below 0.5 ml/kg/h. There is further

tachycardia & blood pressure starts to fall. Patients

become drowsy & mildly confused.

5) Severe shock: There is profound tachycardia &

hypotension. Urine output falls to zero & patients are

unconscious with labored respiration.

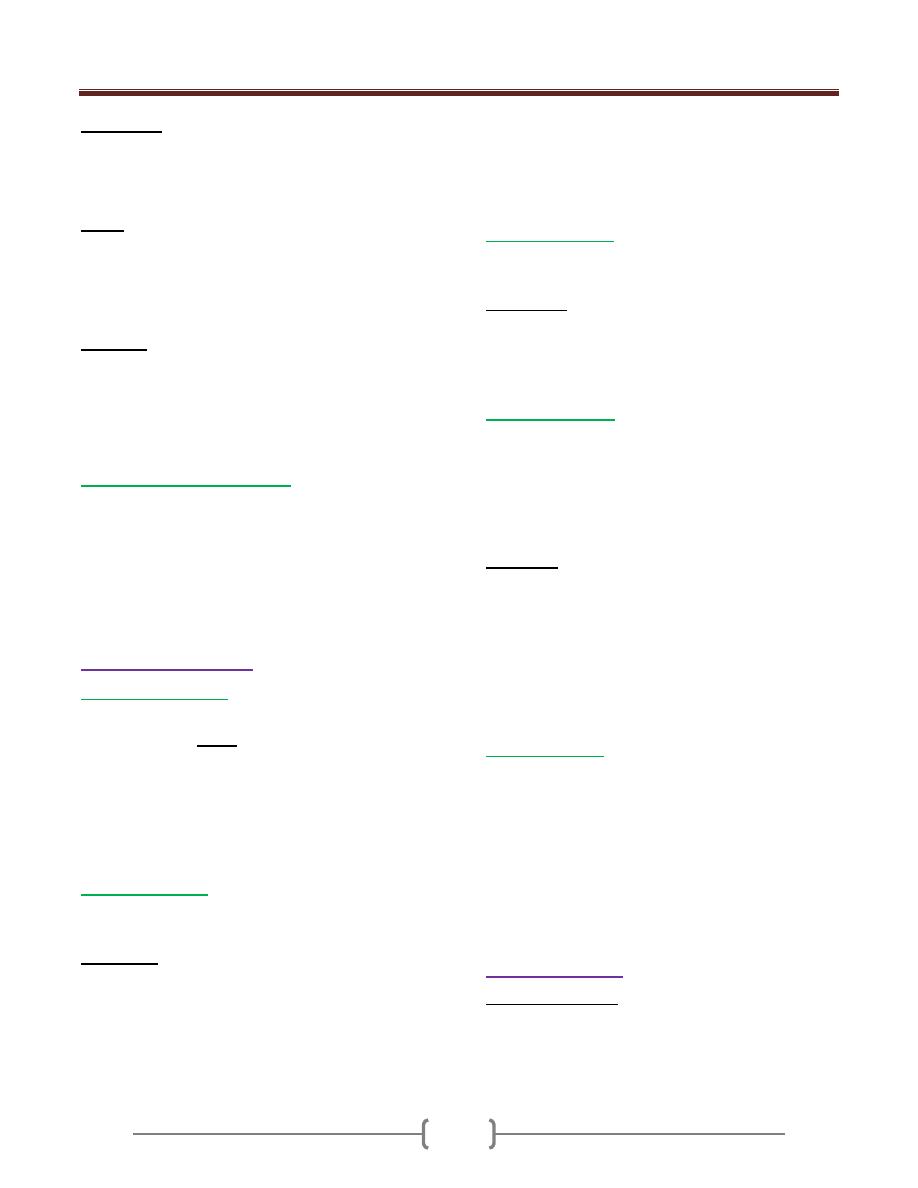

Cardiovascular and metabolic characteristics of shock

Hypovolaemia

Cardiogenic

Obstructive

Distributive

Cardiac

output

Low

Low

Low

High

Vascular

resistance

High

High

High

Low

Venous

pressure

Low

High

High

Low

Mixed

venous

saturation

Low

Low

Low

High

Base

deficit

High

High

High

High

Resuscitation

Should be rapid.

If there is doubt about the cause of shock it is safer to

assume the cause is hypovolaemia & begins with fluid

resuscitation followed by an assessment of the response.

If the general condition of the patient permits, rapid

clinical examination is performed.

In patients who are actively bleeding the resuscitation

should proceed parallel with surgery.

1) Ensure a patent airway & adequate oxygenation &

ventilation.

2) Intravenous access (with short wide- bore catheter) &

blood sample aspirated for cross-matching & blood

should be requested.

3) Intravenous administration of the available fluids

(crystalloid or colloid) while waiting blood Blood

transfusion should be done as early as possible.

4) Vasopressor agents (phenylephrine, noradrenaline) are

used in distributive shock in which there is peripheral

vasodilatation with hypotension despite high cardiac

output.

In cardiogenic shock or when myocardial depression

complicates a shock state inotropic therapy may be

needed to increase cardiac output & therefore oxygen

delivery. The inodilator dobutamine is the drug of choice.

Management of septic shock

1) Admission to intensive care unit of hospital.

2) Care of airway and breathing. Giving oxygen, and may

need mechanical ventilation.

3) Intravenous fluid (Crystalloid or colloid).

4) Antibiotic.

5) Taking history when the condition of patient permits.

6) Control of diabetes.

7) Investigations: Hb, WBC count, RBS, S. electrolytes, B.

urea, S. creatinin. Blood, urine and pus culture may be

needed. Chest X-ray.

8) Surgery: Drainage of pus, gangrene of limb may need

amputation.

9) Care of intravenous line (canula), intercostal tube and

Foley catheter if present.

10) Monitoring

a) Pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate and

temperature

b) Oxygen saturation monitoring

c) Hourly urine output measurement. The best measures

of organ perfusion & the best monitor of the adequacy

of shock therapy remain the urine output.

d) CVP monitoring

e) Electrocardiogram

f) Cardiac output monitoring

g) Level of consciousness (is an important marker of

cerebral perfusion although it is a poor marker of

adequacy of resuscitation).

h) Measures of S. electrolytes and acid base balance.

Lecture 7 - Blood transfusion & blood products

24

Blood transfusion

is the process of transferring blood or

blood-based products from one person (donor) into the

circulatory system of another (recepient). Blood

transfusions can be life-saving in some situations, such as

massive blood loss due to trauma

Blood is made up of various parts, including red blood

cells, white blood cells, platelets, and plasma.

Every person has one of the following blood types: A, B,

AB, or O. Also, every person's blood is either Rh-

positive or Rh-negative. So, if you have type A blood,

it's either A positive or A negative.

The blood used in a transfusion must work with your

blood type. If it doesn't, antibodies (proteins) in your

blood attack the new blood and cause a reaction.

Type O blood is safe for almost everyone. People who

have this blood type are called universal donors. Type O

blood is used for emergencies when there's no time to test

a person's blood type.

People who have type AB blood are called universal

recipients. This means they can get any type of blood.

If you have Rh-positive blood, you can get Rh-positive or

Rh-negative blood. But if you have Rh-negative blood,

you should only get Rh-negative blood.

The indication for B.T. in surgical practice are;

1) 1-Trauma in which there have been severs blood loss.

2) 2-Haemorrhage from pathological lesions, ex.from GIT.

3) 3-Following severe burns, there may be associated

hemolysis

4) 4-Pre-operatively in cases of chronic anaemia in which

surgery is indicated urgently.

5) 5-During major operative procedures in which a certain

amount of blood loss is inevitable, ex.

abdominal operations & cardiovascular operations.

6) 6-Post-operatively in a patient who has become severly

anaemic.

7) 7-To arrest hemorrhage or as a prophylactic measure prior

to surgery in patient with a haemorrhigic state

ex.thrombocytopenia, haemophilia or liver disease.

Preparation of blood products for transfusion

Its important that blood donor should be fit, No evidence

of infection especially hepatitis & HIV infection.

Donated Blood is collected in a sterile bag, with a needle

& plastic tube attached in a complete, closed sterile unit.

15 G needle is introduced into the median cubital vein &

410 ml of blood is aspirated into the bag containing 75 ml

of anticoagulant (citrate,phosphate,dextrose;CPD).blood

can be stored for up to 42 days

During collection, the blood is constantly mixed with the

anticoagulant to prevent clotting.

All blood should be stored in special blood bank

refrigerator at 4C +/-2C.

Prolong storage may cause the following changes;

Leakage of intracellular K

Reduced level 2,3-DPG

Degeneration of functional granulocytes and platelets

Deterioration of clotting V and VIII

Ammonia concentration rises

Decrease in PH

Decrease in RBC deformability and viability

Component separation:

Red cells, plasma and platelets are separated into different

containers and stored in appropriate conditions so that

their use can be adapted to the patient's specific needs.

Red cells work as oxygen transporters, plasma is used as a

supplement of coagulation factors, and platelets are

transfused when their number is very scarce or their

function severely impaired. Blood components are usually

prepared by centrifugation.

Leukoreduction, also known as Leukodepletion is the

removal of white blood cells from the blood product by

filtration. Leukoreduced blood is less likely to cause

alloimmunization (development of antibodies against

specific blood types), and less likely to cause febrile

transfusion reactions.

Blood fractions

Some fractions are more appropriate than whole blood for

some clinical conditions.

1) packed red cells

Advisable in patients with chronic anaemia, elderly, small

children & patients in whom large volume of fluid may

cause cardiac failure. Packed RC is obtained by letting the

blood sediment & removing the plasma or by

centrifugation of whole blood for 15-30minutes.

2) platelet-rich plasma

Suitable for patient with thrombocytopenia.Prepared by

centrifugation of freshly donated blood for 15-30min.

3) platelet-concentrate

For patients with thrombocytopenia.Prepared by

centrifugation of platelet-rich plasma for 15-20 min.

4) plasma

By centrifugation of whole blood

Lecture 7 - Blood transfusion & blood products

25

5) human albumin 4.5%

Repeated fractionation of blood by organic fluids

followed by heat treatment result in this plasma fraction

which is rich in protein.Albumin may be stored for

several months at 4C & are suitable for protein

replacement ex. In severe burns

6) Fresh-frozen plasma (FFP).

Plasma removed from fresh blood within 4 hrs , rapidly

frozen by immersing in a solid Co2 & ethyl alcohol

mixture.This stored at -40 to -50C.Its good source for all

the coagulation factors, albumin & Ig.

Its indicated for surgical patient with abnormal

coagulation due to severe liver failure.Intial dose 12-15

ml/kg (one unit contain200-250ml).It should not be used

as a plasma expander in hypovolemia.

7) Cryoprecipitate.

By thawing FFP at 4C, removing supernatant plasma.The

cryoprecipitate is a very rich source of factorVIII. Its

stored at -40C,its good for haemophilic patients, also

good source of fibrinogen in patient with

hypofibrinogenemia

8) factorVIII&IX concentrate.

These are available in freeze dried form

9) Fibrinogen.

By liquid fractionation of plasma & stored in a dried form

. Used for patients with DIC or congenital

afibrinogenemia, however it carries a high risk of

hepatitis.

10) SAG-Mannitol blood.

All plasma is removed & is replaced with 100 ml of

crystalloid solution containing; Nacl, Adenine, Glucose &

Mannitol. This maintains good cell viability, but contain

no protein (albumin).

Blood grouping & cross-match.

RBCs have many different Ag on their surface.2 main

groups of major importance;

A. Ag of the ABO blood groups;

These are strongly antigenic & are associated with

naturally occurring Abs in the serum.4 different ABO cell

groups;

Red cell group serum contains;

A Anti-B Antibody

B Anti-A Antibody

AB No ABO Antibody

O Anti-A&Anti-B Antibody

B. Ags of the rhesus blood groups

The important Ag in this group is Rh (D) which is

strongly Antigenic & is present in 85% of the population

& Abs to the D Ag are not naturally present in the

remaining 15% but their formation may be stimulated by

the transfusion of Rh +ve.

Such acquired Abs are capable during pregnancy of

crossing the placenta& may cause severe hemolytic

anaemia & even death (hydropes fetalis) in a Rh +ve fetus

in utero.

Incompatibility

If Abs present in the recipients serum are incompatible

with the donors cells ,a transfusion reaction will result

because of agglutination & hemolysis of the donated

cells,leading in sever cases to acute tubular necrosis &

renal failure.So for this reason all transfusion should be

preceeded by;

1-ABO & Rh grouping of the recipient & donor cells , so

that only ABO&Rh(D) compatible blood is given

2-Direct matching of the recipients serum with the donor

cells to confirm compatibility

Blood grouping & cross-matching take 1 hr. If emergency

, blood volume may be restored by

saline,gelatin(ex,haemaccel),dextran or human albumin

4.5%.Alternatively O-ve should be given.

Giving blood.

1) Selection & preparation of the site

2) Checking of the donor blood; compatibility label ,

patients name, hospital reference , ward & blood group

3) Insertion of needle or cannula

4) Giving written instruction, ex, rate of flow. In emergency

it may be necessary to increase rate of flow,its preferable

to give one or two unit in 30 min using a pressure cuff

around a plastic bag of blood

Warming blood.

During rapid major blood transfusion,the blood must be

warmed before reaching the patient by blood warming

unit to reduce the risk of cardiac arrest.

Autotransfusion

Transfusion of patients own blood,ex. In ruptured ectopic

pregnancy when blood is collected from peritoneal cavity

& put in sterile container to give to the patient after

filtering it.

Lecture 7 - Blood transfusion & blood products

26

Complications of BT

A. Immune complications

1) Hemolytic

i. acute

ii. delayed

2) non-hemolytic

i. febrile

ii. urticarial

iii. anaphylactic

iv. pulmonary oedema (non-cardiogenic)

v. graft vs. host

vi. purpura

vii. immune suppression

B. non-immune complications

1) complications associated with massive B.T

i. coagulopathy

ii. citrate toxicity

iii. hypothermia

iv. acid-base disturbance

v. change in serum K concentration

vi. iron accumilation

vii. volume overload

2) infectious complications

i. hepatitis

ii. AIDS

iii. Other viral agents(CMV,EBV,HTLV)

iv. Parasites&bacteria

3) Other complications

i. thrombophlebitis

ii. air embolism

A.

Immune Complication

These are primarily due to the sensitization of the

recipient to donor blood cells (either red or white),

platelets or plasma proteins. Less commonly, the

transfused cells or serum may mount an immune response

against the recipient

1) Hemolytic reactions

Usually involve the destruction of transfused blood cells

by the recipient's antibodies. Less commonly, the

transfused antibodies can cause hemolysis of the

recipient's blood cells. There are acute (also known as

intravascular) hemolytic reactions and delayed (also

known as extravascular) hemolytic reactions.

i. acute hemolytic reactions

The majority of hemolytic reaction are caused by

transfusion of ABO incompatible blood.,eg group A,B or

AB cells to agroup O patient. Most hemolytic reaction are

the result of human error such as error in labeling or

checking the specimen

This type of reaction has been reported to occur

approximately 1 in 25,000 transfusions but it is often very

severe and accounts for over 50% of reported deaths

related to transfusion. The severity of the reaction often

depends in the amount of blood given.

Non-immune hemolysis of RBCs in the blood container

or during administration can occur due to physical

disruption (temperature changes, mechanical

forces,non-isotonic fluid)

The pt. develops chills, fever, nausea chest pain and

flank pain,pain along iv line hypotension, dark urine,

uncontrolled bleeding due to DIC in awake pt.. In

anasthetized pt., you should look for rise in temperature,

unexplained tachycardia, hypotension, hemoglobin

urea, oozing in the surgical field,DIC, shock and renal

shutdown.

Management of acute hemolytic reaction

These patients usually require ICU support and therapy

includes vigorous treatment of hypotension and

maintenance of renal blood flow The unit should be re-

checked. Blood from the recipient patient should be

drawn to test for hemoglobin in plasma, repeat

compatibility testing and coagulation tests. A foley

catheter should be placed to check for hemoglobin in the

urine. Osmotic diuresis with mannitol(or frusemide) and

fluids should be utilized (low-dose dopamine may help

renal function and support blood pressure).dialysis may

be necessary. With rapid blood loss, platelets and fresh

frozen plasma may be indicated.

Prevention:

Proper identification of the pt. from sample collection

through the blood admimistration, proper labeling of

samples and products is essential. Prevention on non-

immune hemolysis requires adherence to proper handling,

storage and administration of blood products

ii. Delayed hemolytic reactions

Pts may develop Abs to red cells Ags (Ab. To non-D Ag

of the Rh system or to the kell,duffy or kidd Ags).

Antibodies can occur naturally, or may arise as a

consequence of previous transfusion or pregnancy. .

Following a normal, compatible transfusion there is a 1-

1.6% chance of developing antibodies to these foreign

antibodies (alloimmunisation). This takes weeks or

months to happen - and by that time, the original

Lecture 7 - Blood transfusion & blood products

27

transfused cells have already been cleared. Re-exposure to

the same foreign antigen can then cause an immune

response.

Most delayed haemolytic reactions produce few

symptoms and may go unrecognised, however, there may

be malaise, jaundice, fever, a fall in Hematocrit despite

transfusion, and an increase in unconjucated bilirubin.

Diagnosis may be facilitated by the direct coombs test

which can detect the presence of antibodies on the RBC

membrane

Alloimmunisation to the D andK (Kell) antigens is

prevented by the provision of Rh(D) negative and Kell

negative blood for Rh(D) negative, kell negative pts. This

is important for females with child-bearing potential as

these antibodies can cause sever hemolytic disease of the

newborn during pregnancy

2) Non-hemolytic reaction

Are Due to sensitization of the recipient to donor WBC,

platelets, or plasma proteins. These reactions include;

i. Febrile Reactions

Cause: Fever and chills during transfusion without

evidence of hemolysis are thought to be caused by

recipient antibodies reacting with white cell antigens or

white cell fragments in the blood product or due to

cytokines which accumulate in the blood product during

storage. Fever occurs more commonly with platelet

transfusion (10-30%) than red cell transfusion (1-2%).It is

important to distinguish from fever due to the patient's

underlying disease or infection (check pretransfusion

temperature). Fever may be the initial symptom in a more

serious reaction such as bacterial contamination or

haemolytic reaction.

Management: Symptomatic, paracetamol

If the fever is accompanied by significant changes in

blood pressure or other signs and symptoms, the

transfusion should be ceased and investigated.

Prevention: A proportion of patients who have febrile

reactions will have similar reactions to subsequent

transfusions. Many are prevented by leucocyte filtration

(either bedside or pre-storage).

ii. Urticarial (allergic)reactions

Are characterized by erythema, hives and itching

without fever. on rare occasions it may be associated with

laryngeal oedema and bronchospasm. Again, this is a

relatively common reaction and occurs in about 1% of all

transfusions. It is thought to be due to sensitization

against plasma proteins. The use of packed red blood cells

rather than whole blood has decreased the likelihood of

this problem.

Management; If urticaria occurs in isolation (without

fever and other signs), slow the rate or temporarily stop

transfusion. If symptoms are bothersome, consider

administering an antihistamine before restarting the

transfusion. If associated with other symptoms, cease the

transfusion and proceed with investigation.

iii. Anaphylactic reactions

Are rare and occur in about 1 of 150,000 transfusions.

These are severe reactions that can occur with very small

amounts of blood (a few milliliters). Typically, these

reactions occur in pts with IgA deficiency who have anti-

IgA antibodies. These antibodies react to transfusions

containing IgA.

Anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions have signs of

cardiovascular instability including hypotension,

tachycardia, loss of consciousness, cardiac arrhythmia,

shock and cardiac arrest. Sometime respiratory

involvement with dyspnea and stridor are prominent.

IgA deficiency occurs in 1 of 600-800 patients in the

general population. Patients with known IgA deficiency

should receive washed packed red blood cells, or IgA free

blood units

Management by immediately stop transfusion,

supportive care including airway management may be

required. Adrenaline may be indicated. Usually given as

1;1000 solution s.c,i.m or slow i.v.,fluids and

corticosteroids

iv. Transfusion-related acute lung injury

Some pts can develop acute hypoxemia and non-

cardiogenic pulmonary oedema and present with a

picture that looks like adult respiratory distress syndrome

(ARDS) developing within 2-8 hrs hours after a

transfusion. This is a rare (1 in 5000) but serious

complication that is thought to be secondary to cytokines

in the transfused product or from interaction between

donar antileucocyte antibodies with the patient white cells

antigens (or vice versa) causing them to aggregate in the

pulmonary circulation. Subsequent damage to the

alveolocapillary membrane triggers the syndrome.

Treatment involves symptomatic support for respiratory

distress includes oxygen administration and may require

Lecture 7 - Blood transfusion & blood products

28

intubation and mechanical ventilation . symptoms

generally resolves over 24-48 hours.

v. Graft versus Host disease

This seen exclusively in immunocompromised patients

when donor lymphocytes proliferate and damage target

organs especially bone marrow, skin, liver and

gastrointestinal tract. The clinical syndrome comprises

fever, skin rash, pancytopenia, abnormal liver function

and diarrhoea and is fatal in over 80% of cases. The usual

onset is 8-10 days post transfusion, with a longer interval

between transfusion and onset of symptoms in infants.

Prevention: Gamma irradiation of cellular blood products

(whole blood, red blood cells, platelets, granulocytes) for

at risk patients.(pts with hodgkins disease, aplastic

anaemia, AIDS, cytotoxic drugs)

vi. Post-transfusion purpura

is common with the development of platelet antibodies.

The external purpura signal a reaction that may lead to

profound thrombocytopenia which usually occurs about

one week post transfusion. Plasmapheresis is the

recommended treatment.

vii. Immune suppression

is a debatable complication. The transfusion of leukocyte-

containing blood products appears to be

immunosuppressive causing a decrease in Natural Killer

cell function, decreased phagocytosis and decreased

helper to suppressor cell ratios.

The effect was first seen in renal transplant patients in

whom preoperative blood transfusions appeared to

improve graft survival.

B.

Non-Immune Complications

1) complications associated with massive B.T

Massive Transfusion is usually defined as the need to

transfuse a volume of blood equivalent or exceeding the

patients own volume in a less than a 24-hours period or

replacement of more than one blood volume in 24 hours

or more than 50% of blood volume in 4 hours.(adult

blood volume is approximately 70 ml/kg, in children over

1 months old is approximately 80 ml/kg.

Massive transfusion occurs in settings such as severe

trauma, ruptured aortic aneurysm, surgery and obstetrics

complications.

i. Coagulopathy

Is common with massive transfusion. The most common

cause of bleeding following a large volume transfusion is

dilutional thrombocytopenia(each 10-12 units can

produce a 50% fall in the platelet count, thus, significant

thrombocytopenia can be seen).

Alteration in clotting system may occur, it can be

preexisting or induced coagulopathy. Its usually related to

the effects of acidosis and hypothermia. Acidosis

interfere with the assembly of coagulation factor

complexes involving calcium. Hypothermia reduces the

enzymatic activity of plasma coagulation proteins and

prevent platelets activation

ii. Citrate toxicity

Citrate is the anticoagulant used in blood products. It is

usually rapidly metabolised by the liver. Rapid

administration of large quantities of stored blood(one unit

over five minutes or so ) may cause hypocalcaemia and

hypomagnesaemia when citrate binds calcium and

magnesium. This can result in myocardial depression or

coagulopathy.

Patients most at risk are those with liver disease or

dysfunction or neonates with immature liver function

having rapid large volume transfusion.

Management: Slowing or temporarily stopping the

transfusion allows citrate to be metabolised. Replacement

therapy with intravenous calcium administration may be

required if there is clinical(transient tetany, hypotensiov)

or ECG or lab evidence of hypocalcemia or

hypomagnesaemia

iii. Hypothermia

Rapid infusion of large volumes of stored blood

contributes to hypothermia. Infants are particularly at risk

during exchange or massive transfusion.

Prevention and Management: Appropriately maintained

blood warmers should be used during massive or

exchange transfusion

iv.

v. Acid-Base imbalance

can be seen after massive transfusion. The most common

abnormality is a metabolic alkalosis. Patients may

initially be acidotic because the blood load itself is acidic

and there may be a prevailing lactic acidosis from

hypoperfusion. However, once normal perfusion is

restored, any metabolic acidosis resolves and the citrate

and lactate are then converted to bicarbonate in the liver.

Lecture 7 - Blood transfusion & blood products

29

vi. Potassium Effects

Serum potassium can rise as blood is given. The

potassium concentration in stored blood increases steadily

with time (stored red cells leak potassium proportionally

throughout their storage)..

hyperkalaemia can occur during rapid, large volume

transfusion of older red cell units in small infants and

children.

Prevention: Blood less than 7 days old is generally used

for rapid large volume transfusion in small infants (eg

cardiac surgery,exchange transfusion)

vii. Iron accumulation

Iron accumulation is a predictable consequence of chronic

RBC transfusion. Organ toxicity begins when

reticuloendothelial sites of iron storage become saturated.

Liver and endocrine dysfunction creates significant

morbidity and the most serious complication is

cardiotoxicity which causes arrhythmias, and congestive

heart failure. Patients receiving chronic transfusion

usually have their iron status monitored and managed by

their physician.

Management and Prevention: Iron chelation therapy is

usually commenced early in the course of chronic

transfusion therapy

viii. Volume overload

Pts with cardiopulmonary disease and infants are at risk

of volume overload especially during rapid transfusion of

large volume of blood

Management; : Stop the transfusion, administer oxygen

and diuretics as required.its advisable in chronic anaemia

to give packed RC in addition to diuretic.The transfusion

should be given slowly(one unit over 4-6hrs).

2) Infectious complications

Hepatitis May be transmitted from donor & cause sever

hepatitis , usually 3 mths after transfusion. it should be

avoided by screening of the blood donor.

AIDS is a feared disease but the actual risk is quite low.

All blood is tested for the anti-HIV-1 antibody which is a

marker for infectivity. Unfortunately, there is a 6-8 week

period required for a person to develop the antibody after

they are infected with HIV and therefore infectious units

can go undetected

CMV and EBV are usually the cause of only

asymptomatic infection or mild systemic illness.

Unfortunately, some of these people become

asymptomatic carriers of the viruses and the white blood

cells in blood units are capable of transmitting either

virus.

Immunocompromised and immunosuppressed

patients are particularly susceptible to CMV and should

receive CMV negative units only.

Parasitic diseases

Reported to be transmitted via blood transfusion include

malaria, toxoplasmosis, and Chagas' disease.

Bacterial Contamination

Bacteria may be introduced into the pack at the time of

blood collection from sources such as donor skin, donor

bacteraemia or equipment used during blood collection or

processing.or it may results from faulty storage,especially

when donor blood being Left in a warm room for some

hrs before transfusion

Bacteria may multiply during storage. Gram positive and

Gram negative organisms have been implicated. Platelets

are more frequently implicated than red cells.

Symptoms: Very high fever, rigors, profound

hypotension, nausea and/or diarrhoea.

Management: Immediately stop the transfusion and

notify the hospital blood bank.

After initial supportive care, blood cultures should be

taken and broad-spectrum

antimicrobials commenced. Laboratory investigation will

include culture of the blood pack.

Prevention: Inspect blood products prior to transfusion.

Some but not all bacterially contaminated products can be

recognised (clots, clumps, or abnormal colour).

Maintaining appropriate cold storage of red cells in a

monitored blood bank refrigerator is important.

Transfusions should not proceed beyond the

recommended infusion time (4 hours).

Blood substitutes

1) Albumin

Human albumin can be used while cross-matching is

being performed.2-3 units are given IV over 30min.Its

valuable in burns & hypovolemia. Its prepared from

human plasma & heat treated so that neither hepatitis nor

Lecture 7 - Blood transfusion & blood products

30

HIV can be transmitted.Shelf life is one year at room

temp. but 5-yr at 2-8C

Human albumin(4.5%) is valuable in burn&hypovolemia.

Human albumin(20%) concentrated salt poor used in

sever hypoalbuminemia with salt&water overload ex.

Liver failure with ascitis.

2) 2-Dextrans

These are polysaccharide polymers of varying molecular

wt.ex.dextran70 & dextran40.

It produce an osmotic pressure similar to that of

plasma.They induce roulex of the red cells,thus interfere

with blood grouping&cross-matching,so the need of

blood sample before hand.It interfere with platelets

function & may cause an abnormal bleeding,so its

recommended that total volune of dextran should not

exceed 1000ml.It may also cause;

anaphylactic reaction.dextran may also cause;

- simple haemodilution of clotting factors

- Reduced factorVIII activity

- Increased fibrinogen activity

- Increased fibrinolysis

- Reduced clotting strength

- Impairment of platelets function

3) Gelatin(ex.Haemaccel,Gelofusin)

Used commonly as plasma expander.Up to 1000ml of 3.4-

4% solution givenIV.It has low rate of anaphylactic

reaction

4) Hydroxyethyl starches

Many types;Haptostarches,Pentastarches,Tetrastarches.It

has low incidence of anaphylactic reaction.It may cause

intractable itching,coagulopathy may occur due to

reduction in factor VIII& platelets

\

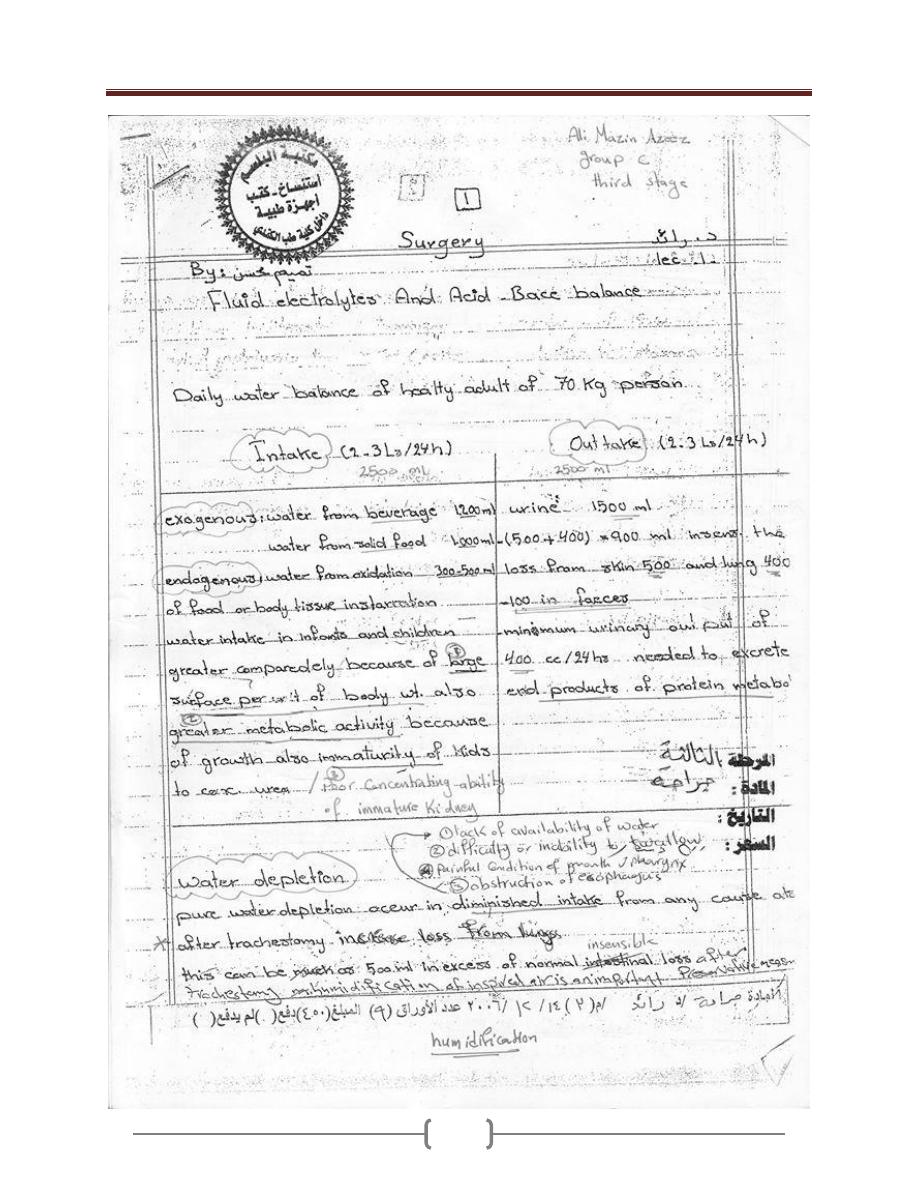

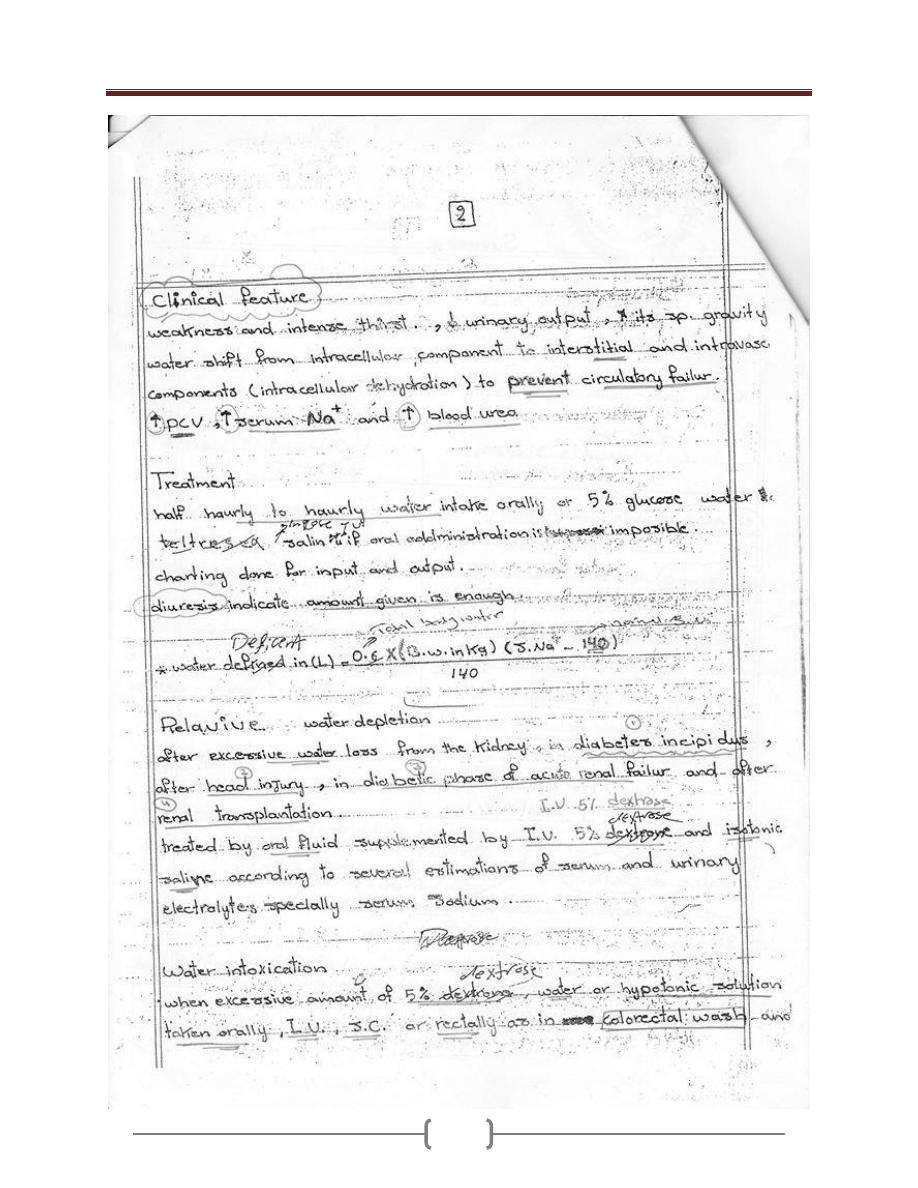

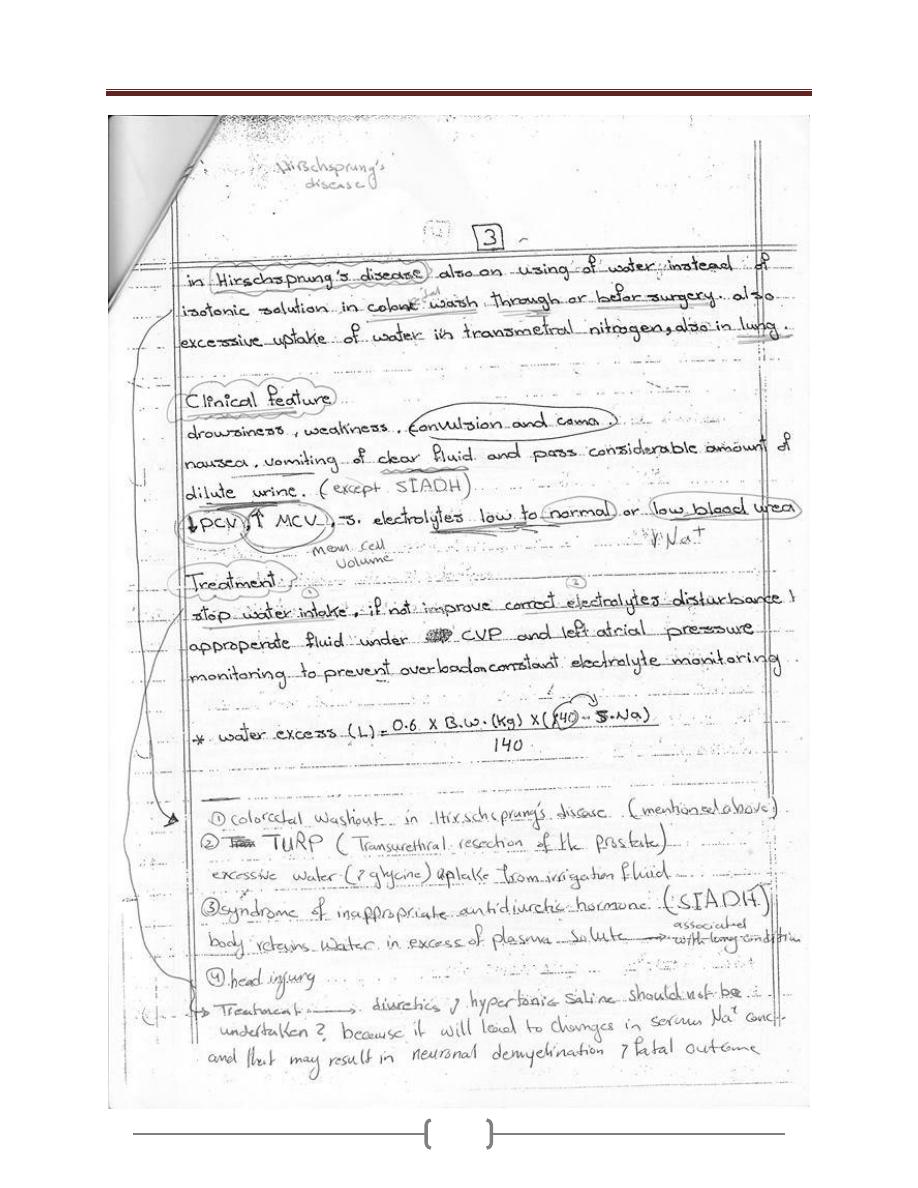

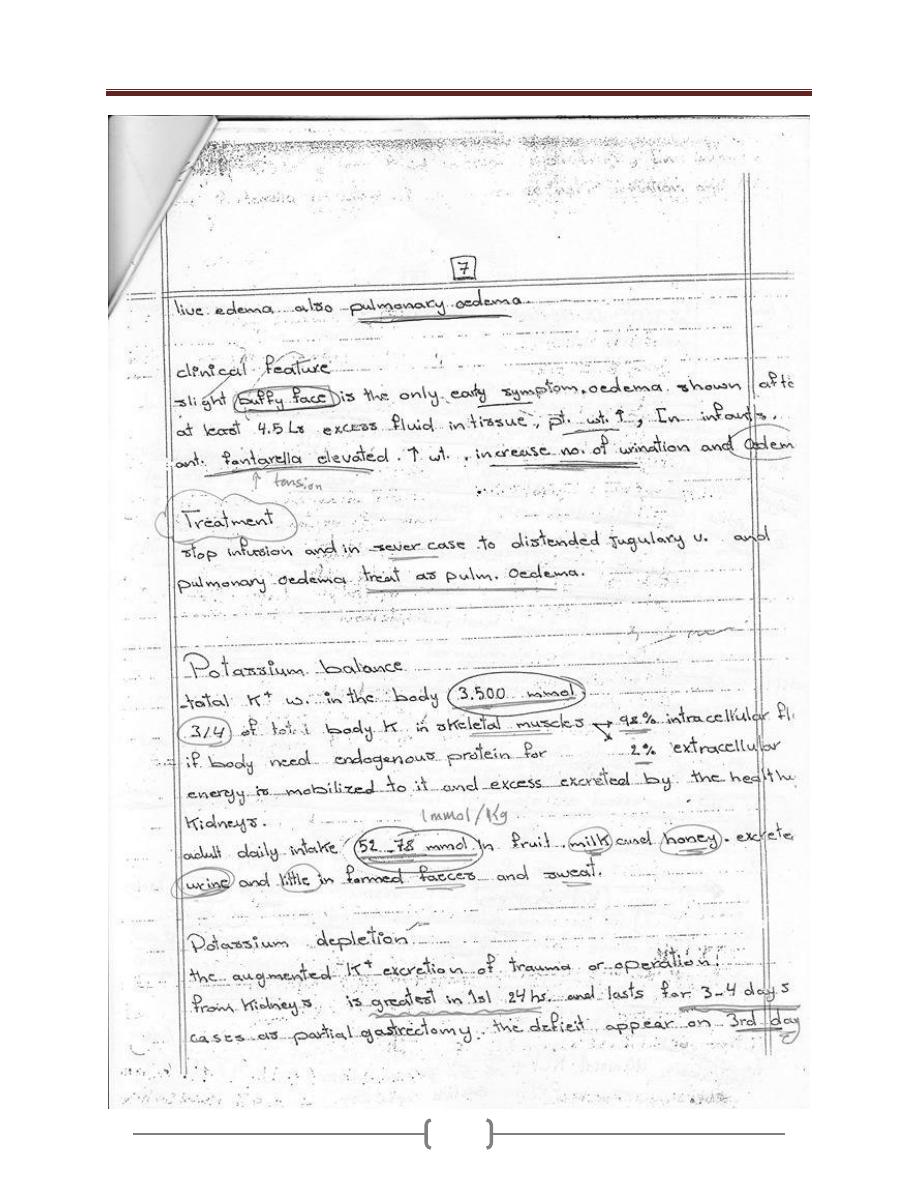

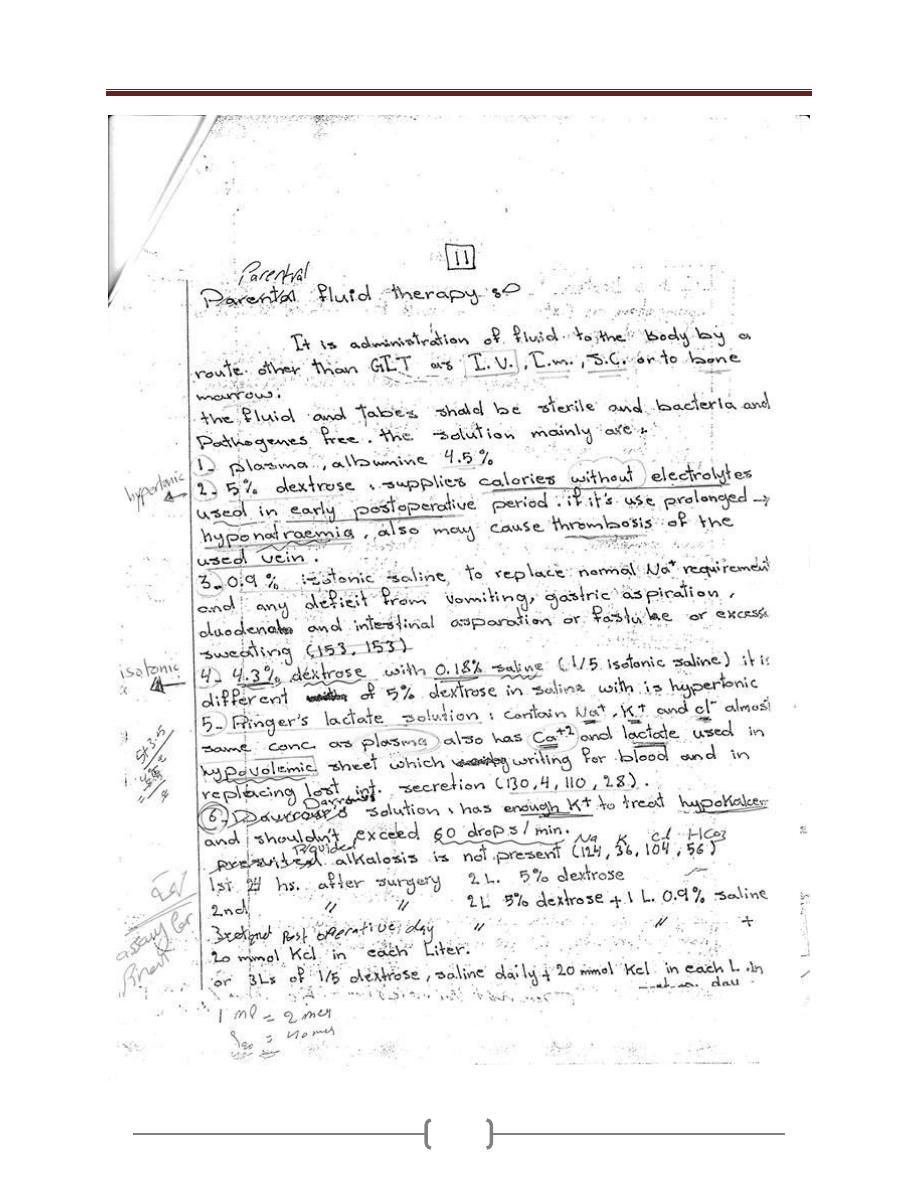

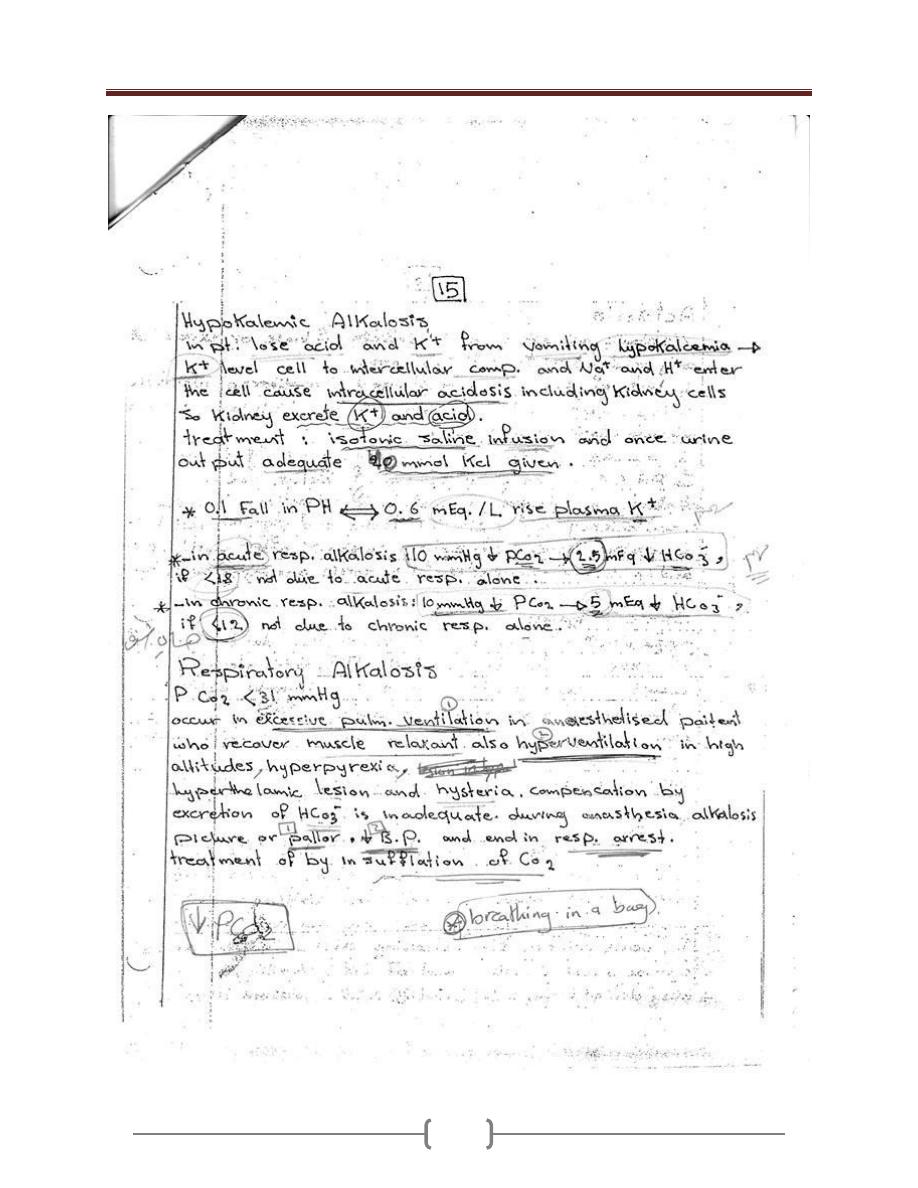

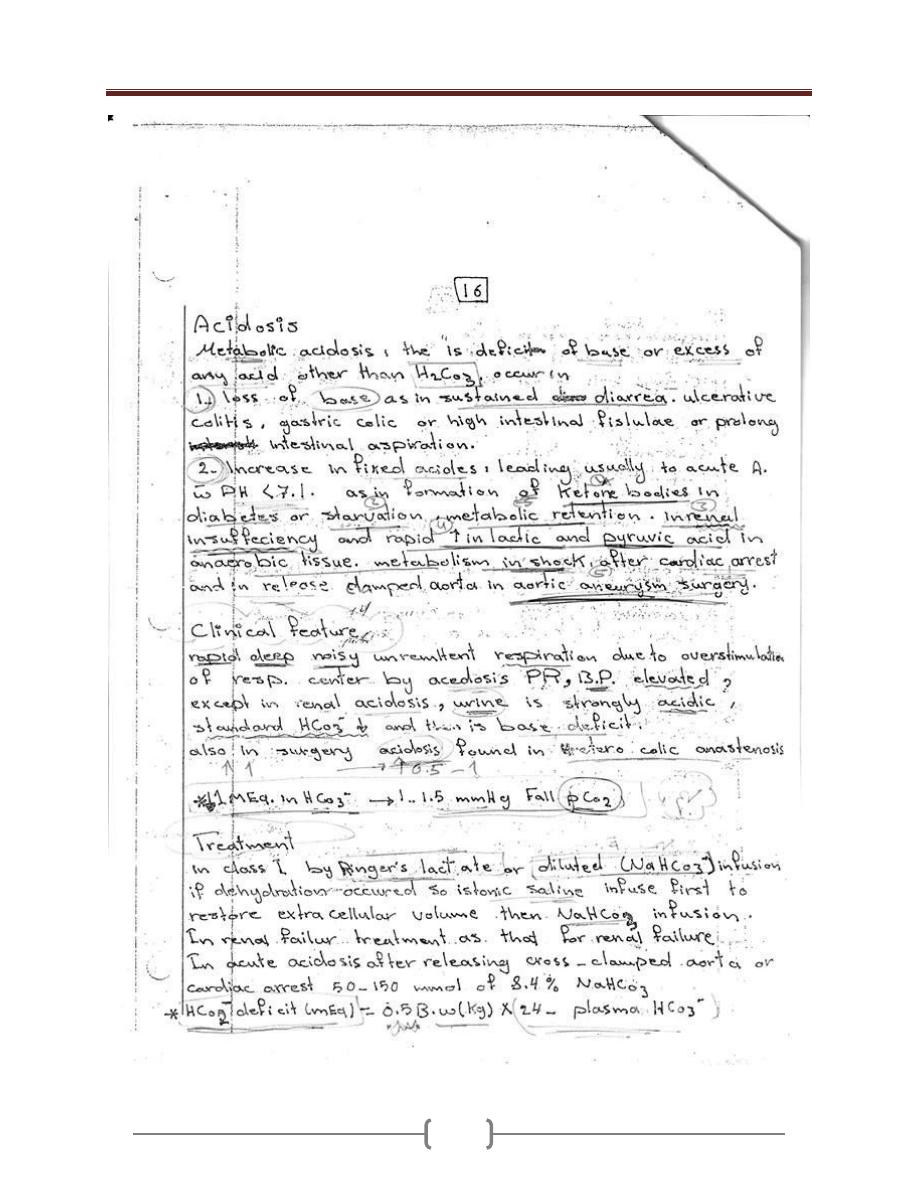

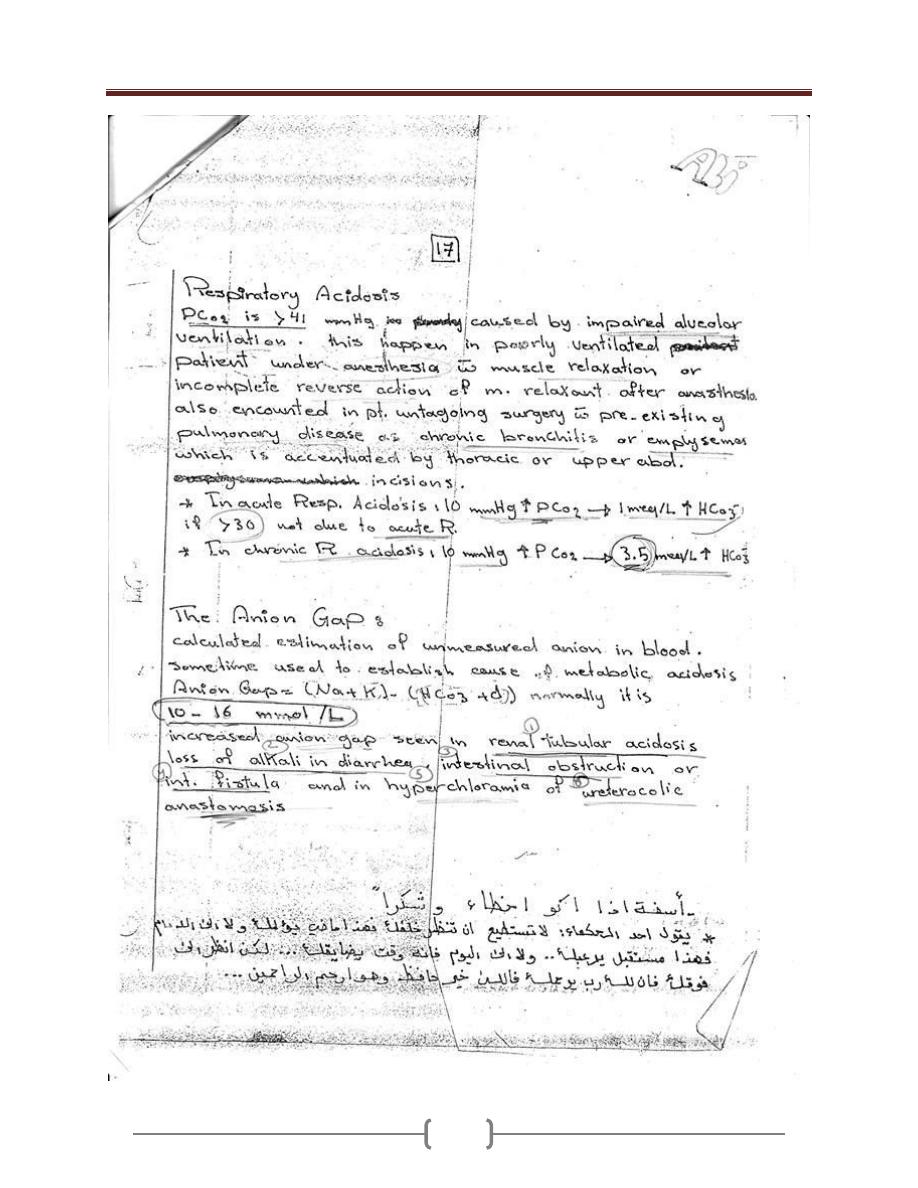

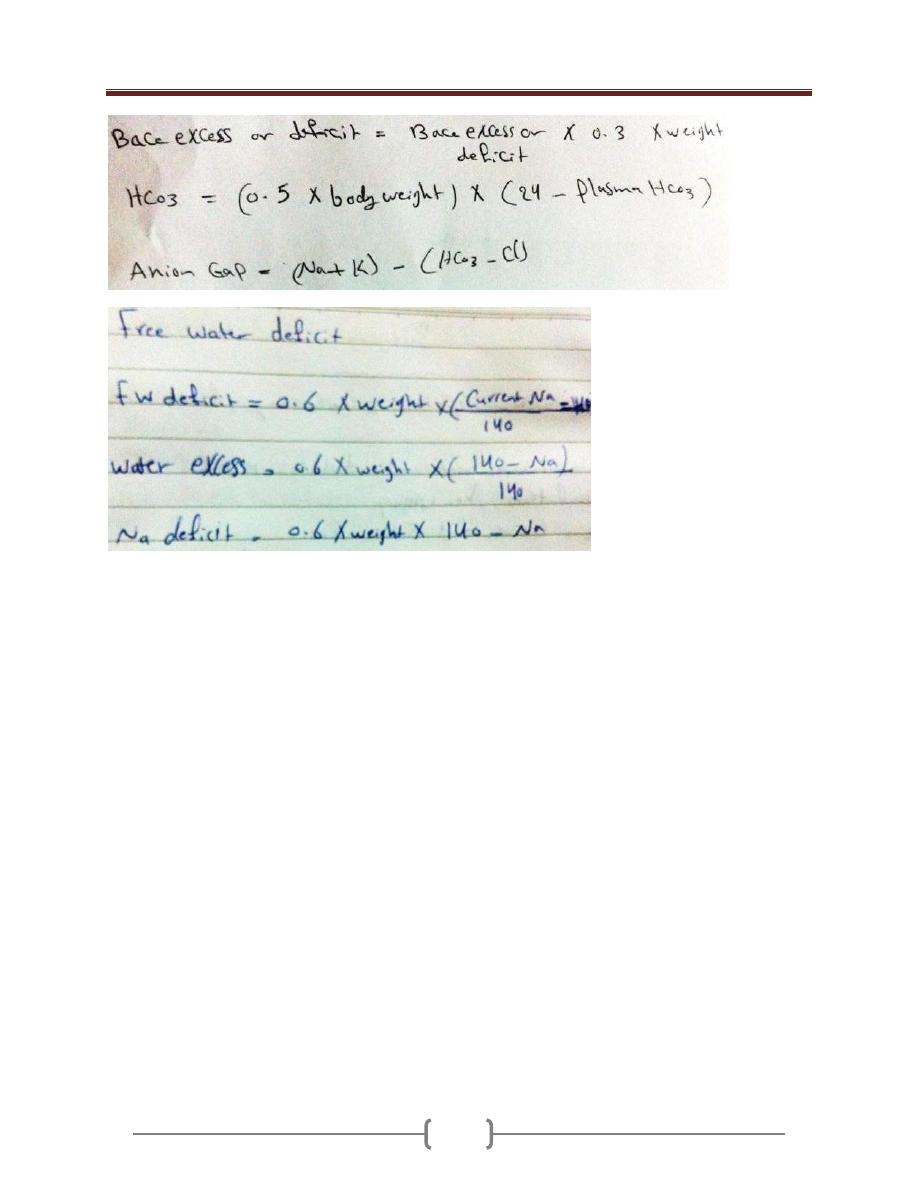

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

31

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

32

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

33

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

34

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

35

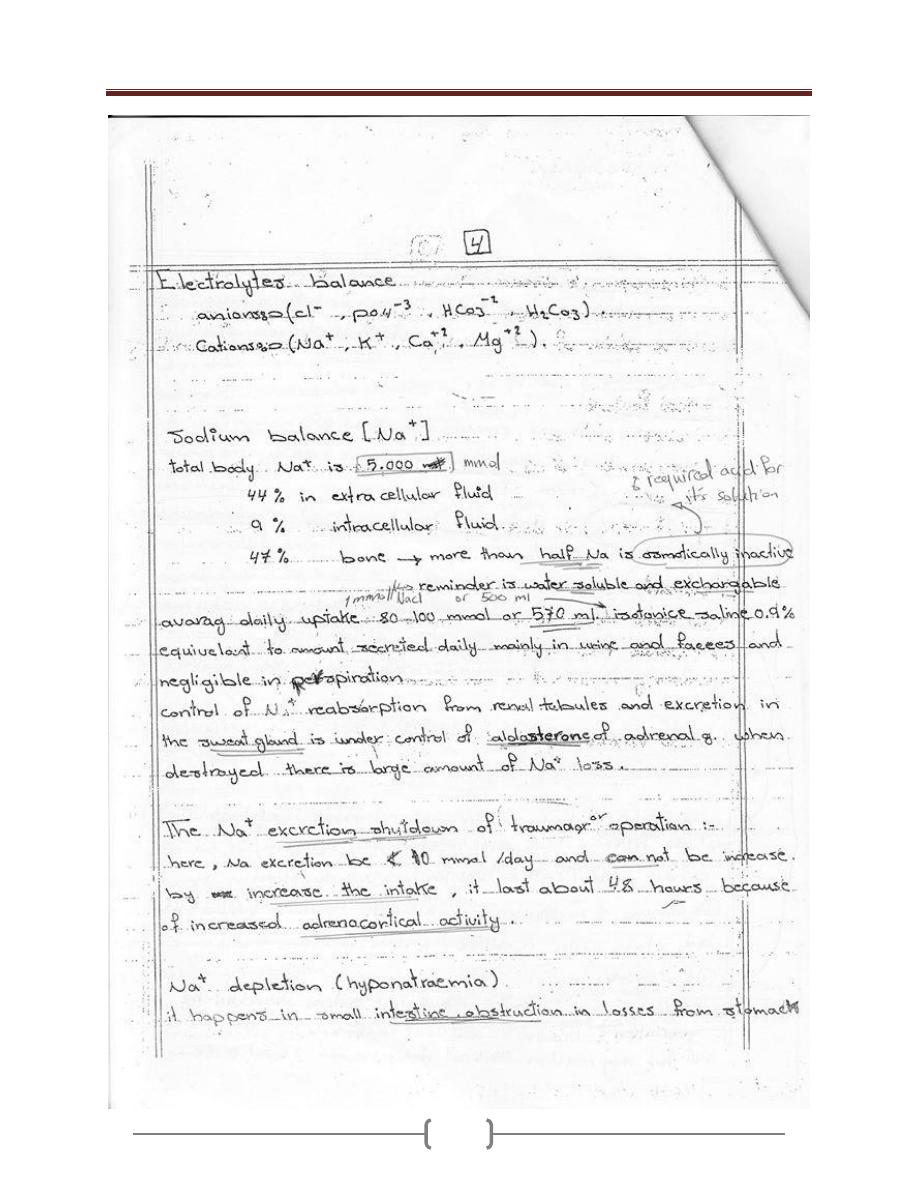

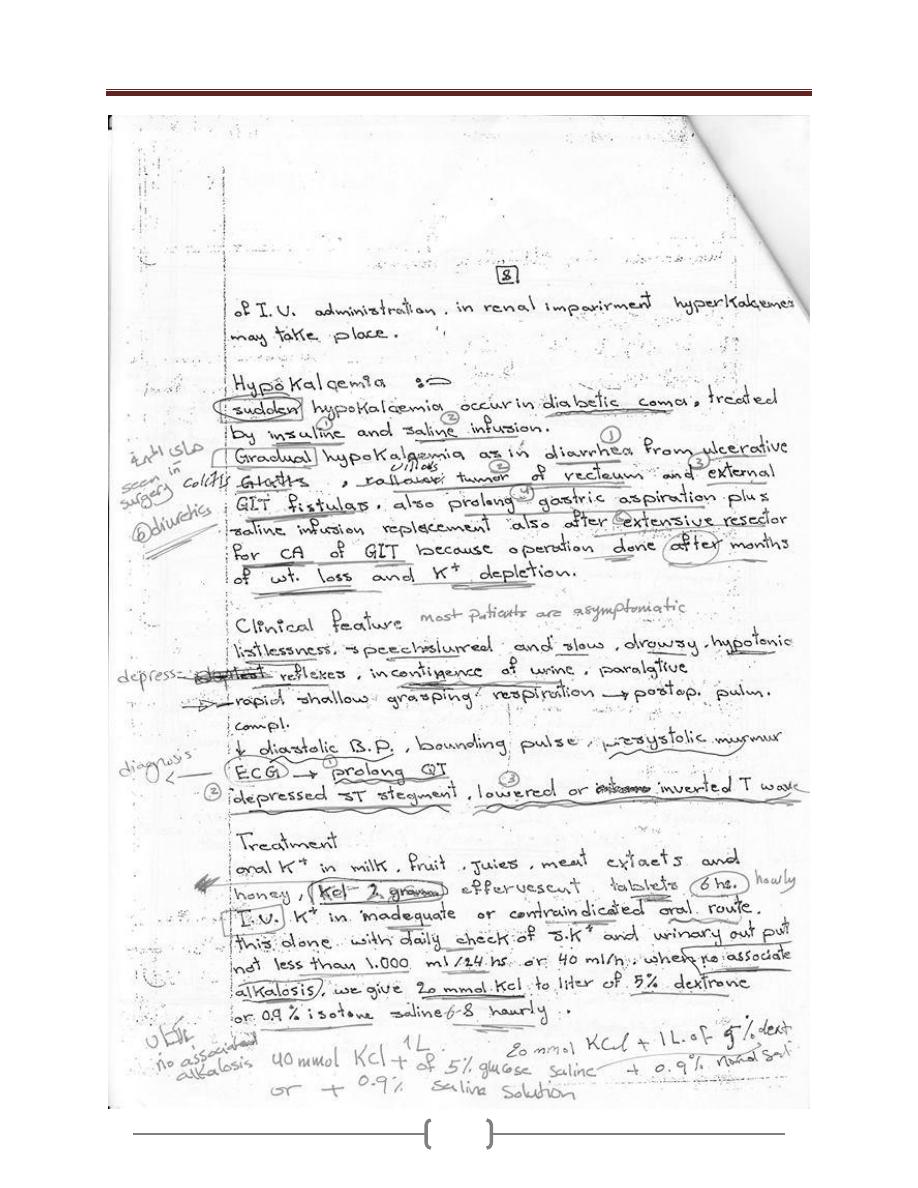

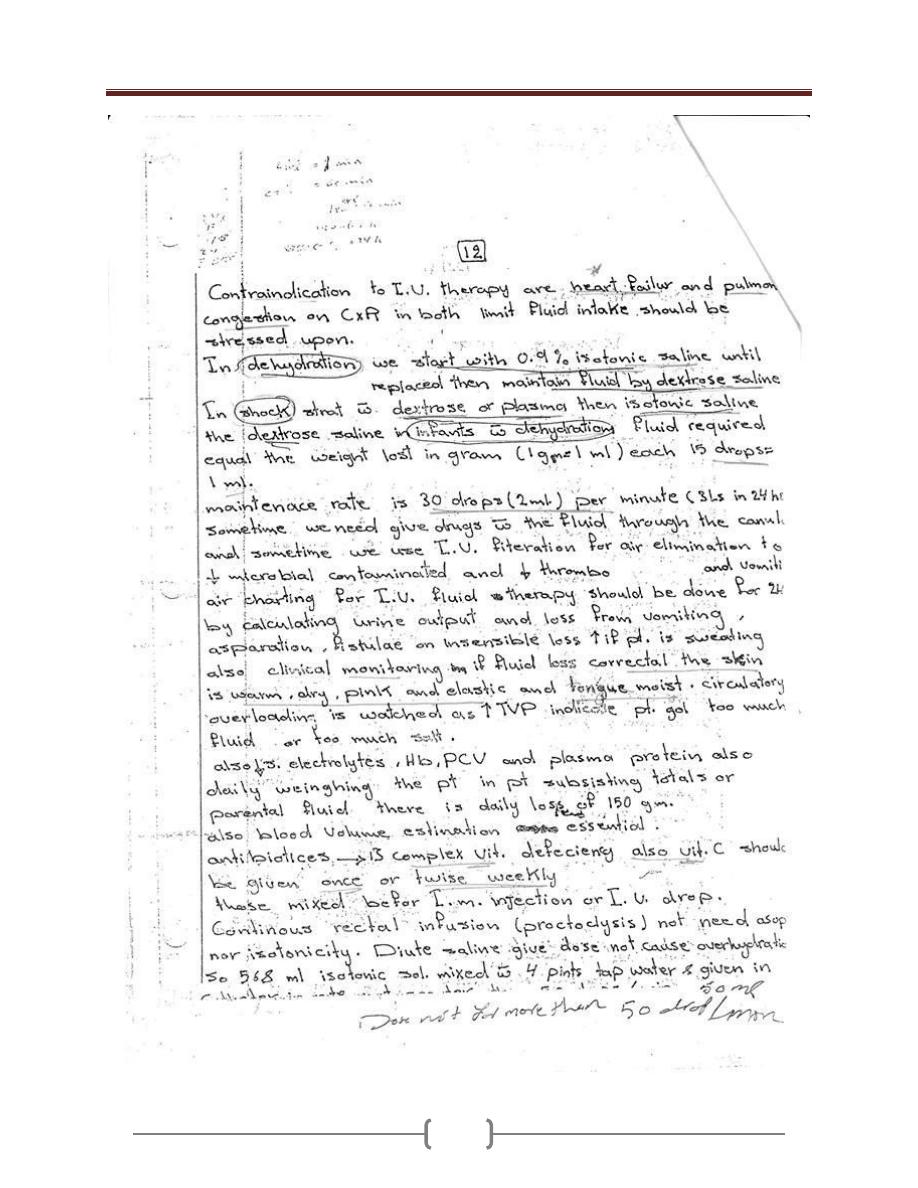

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

36

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

37

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

38

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

39

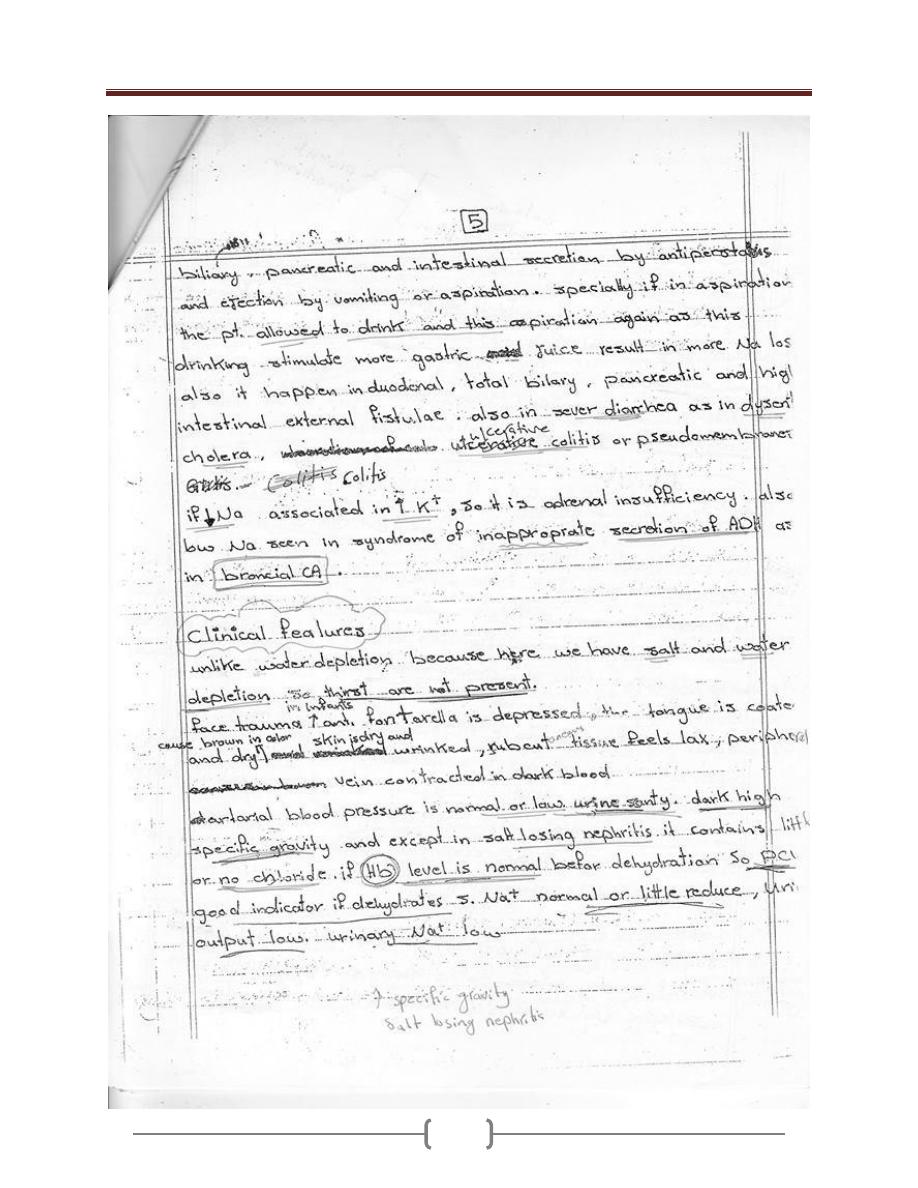

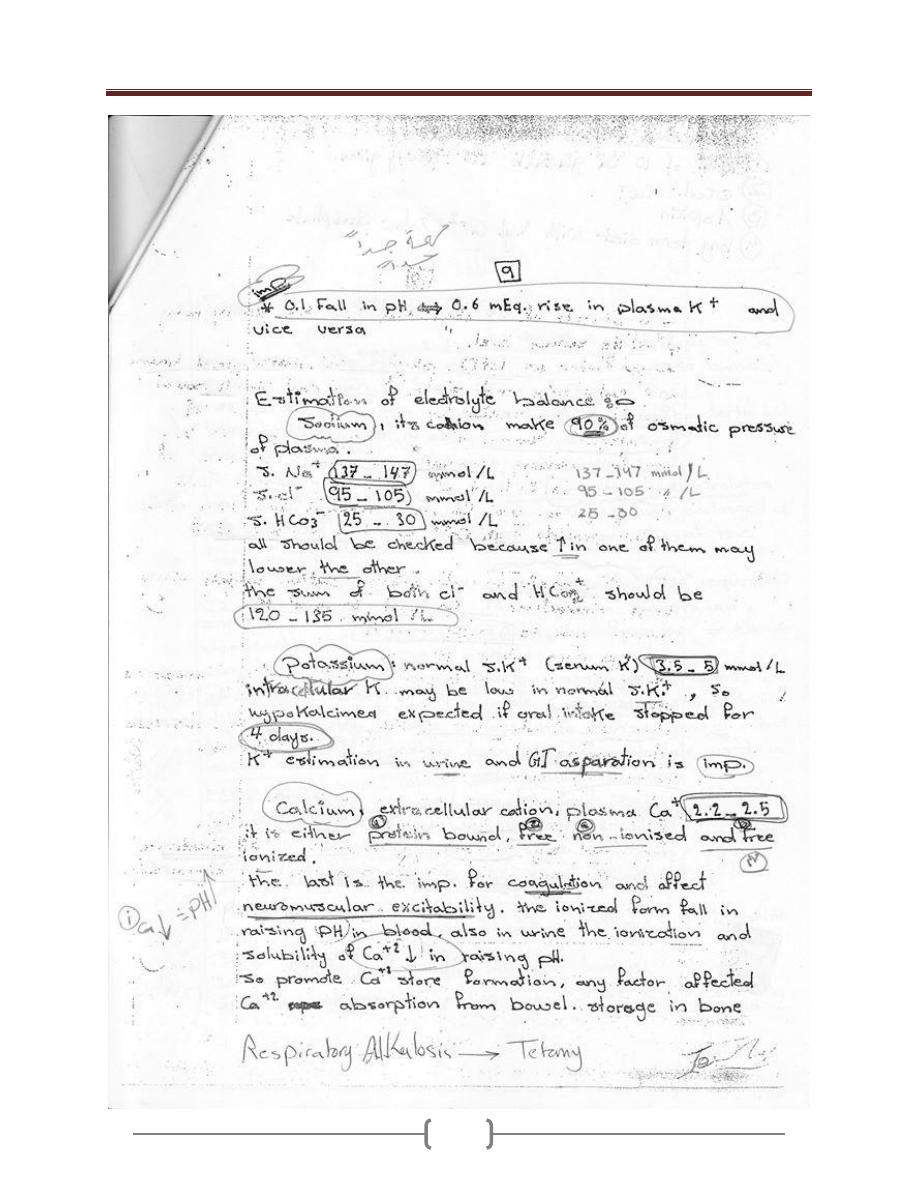

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

40

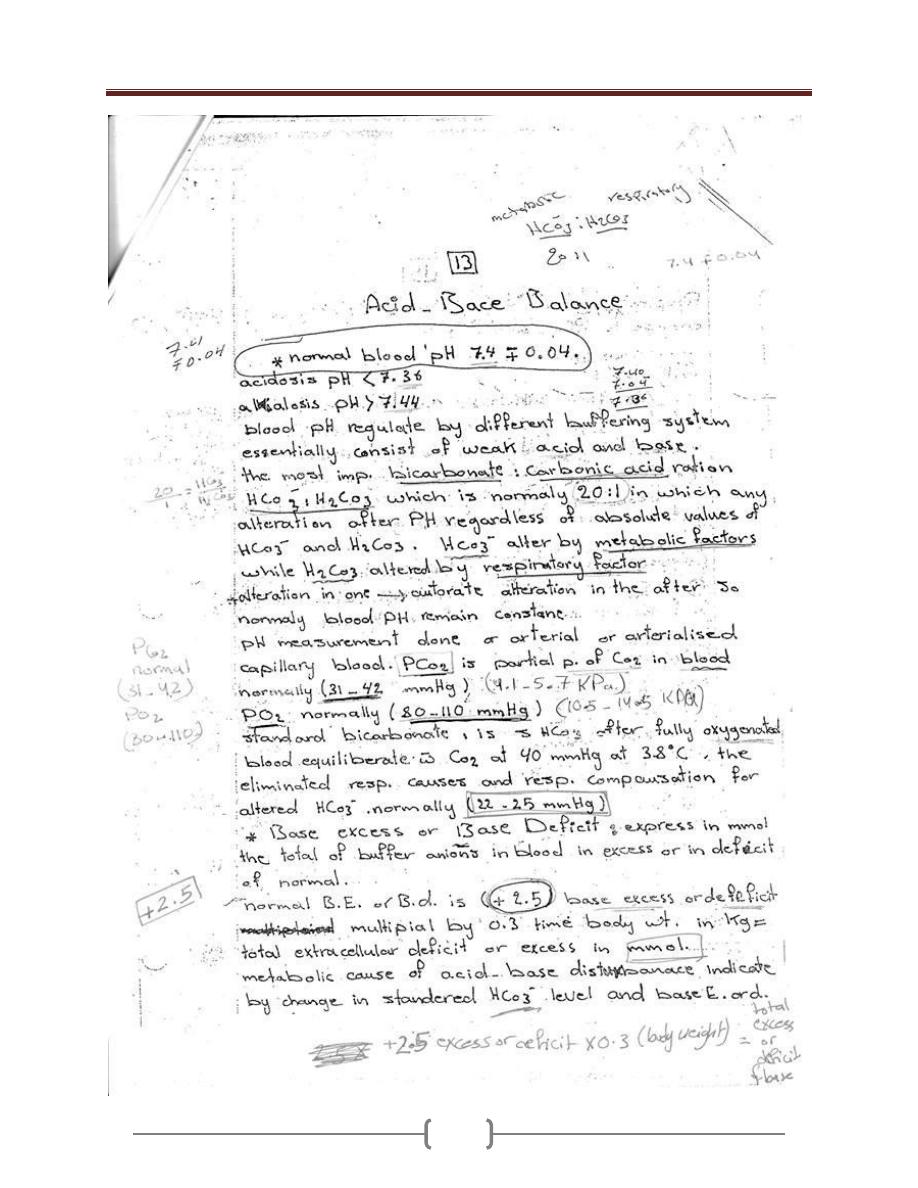

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

41

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

42

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

43

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

44

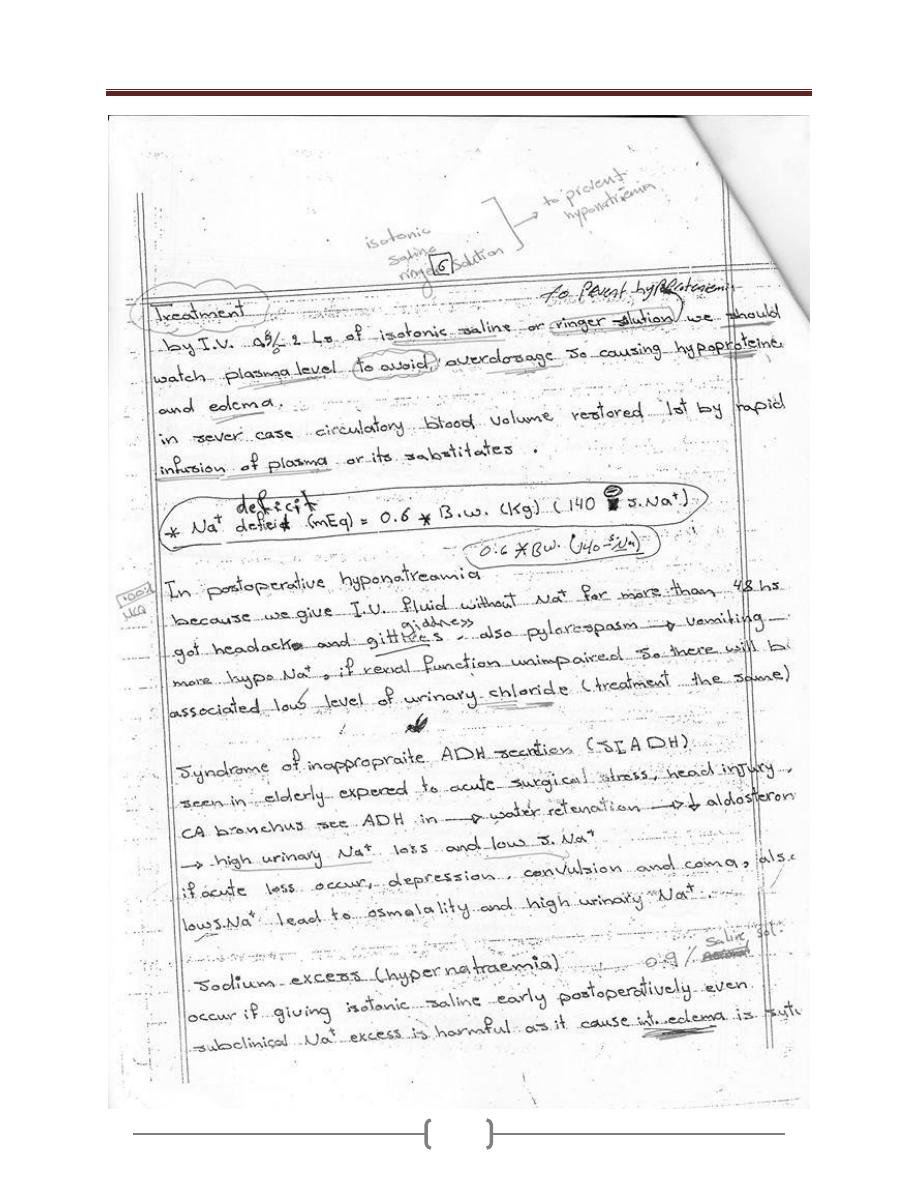

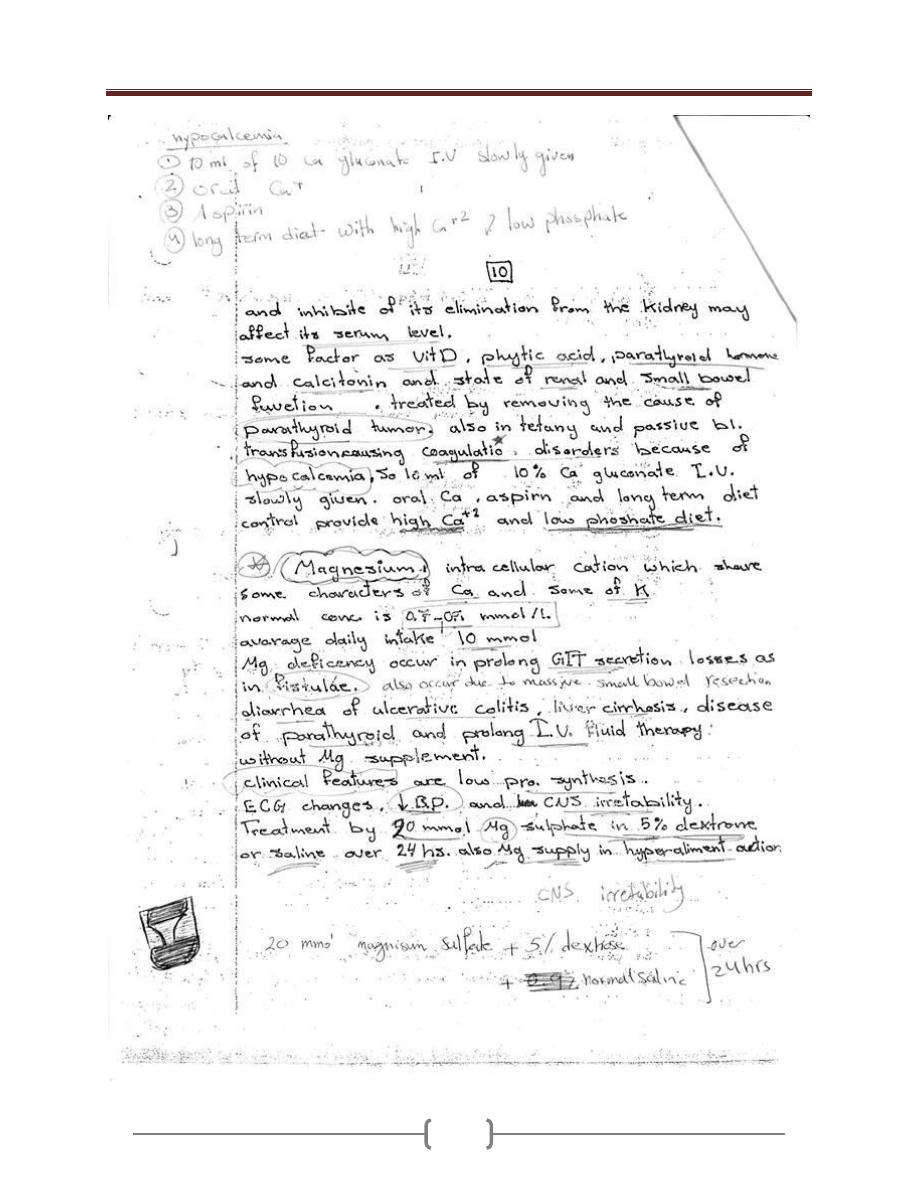

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

45

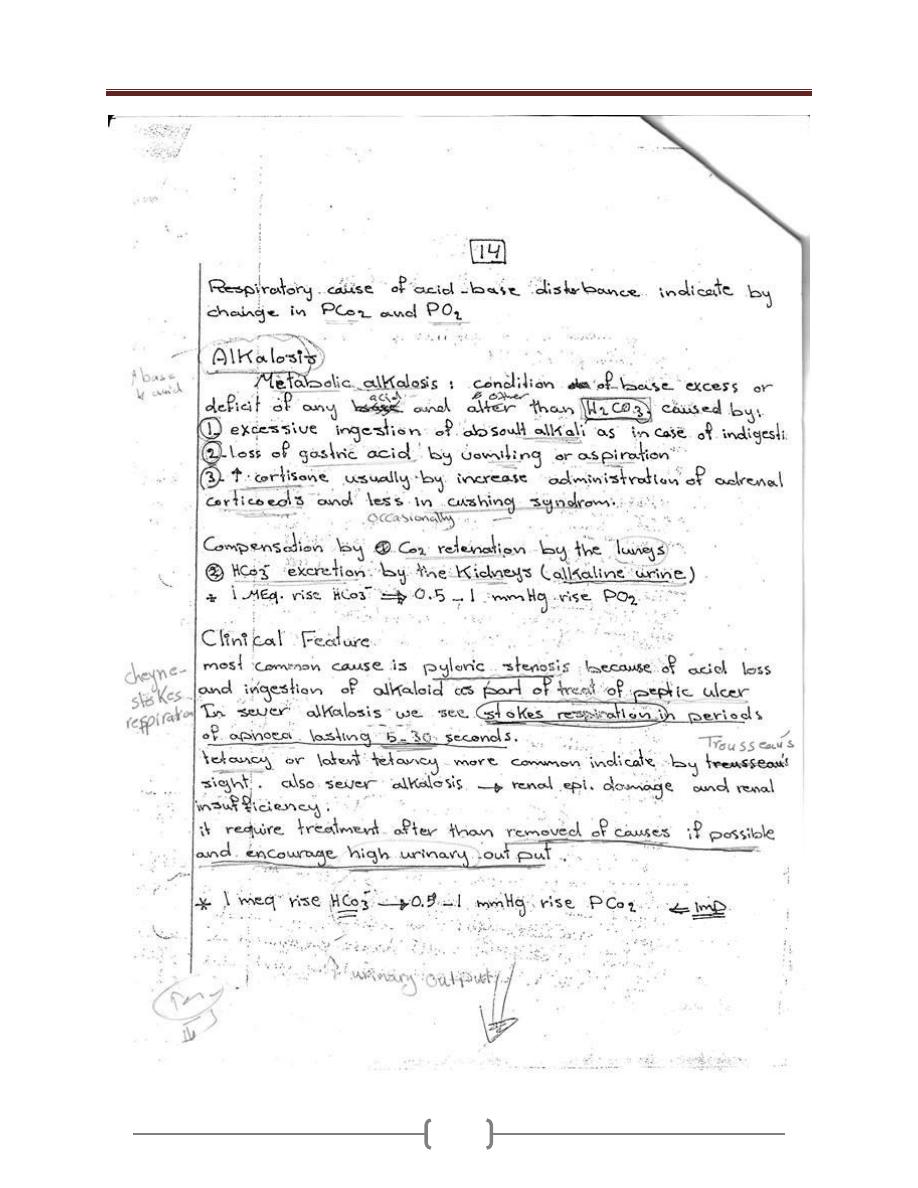

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

46

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

47

Lecture 8+9 – Fluid Electrolyte & Acid-Base balance

48

Lecture 10+11 - Operating Room Sterilization & Sterile precautions

49

Lecture 10+11 - Operating Room Sterilization & Sterile precautions

50

Lecture 10+11 - Operating Room Sterilization & Sterile precautions

51

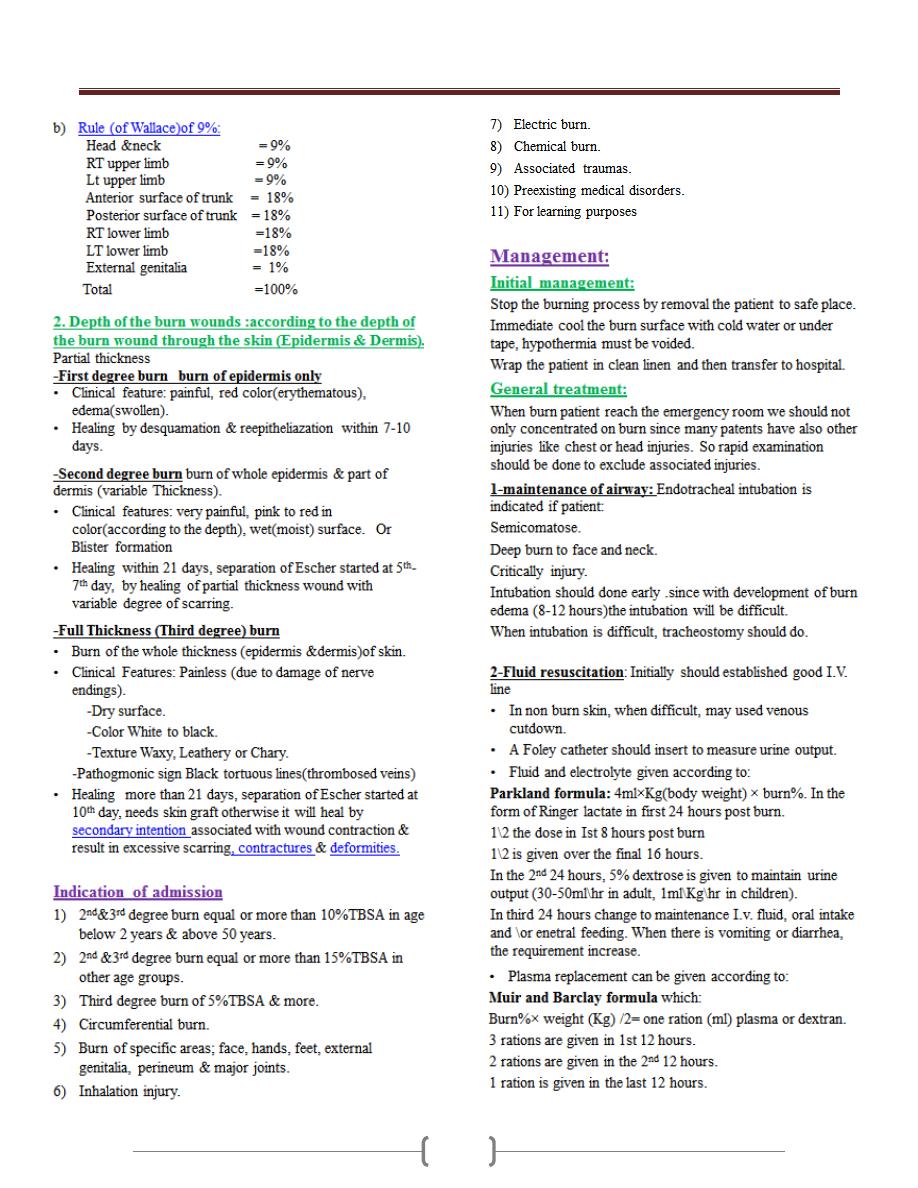

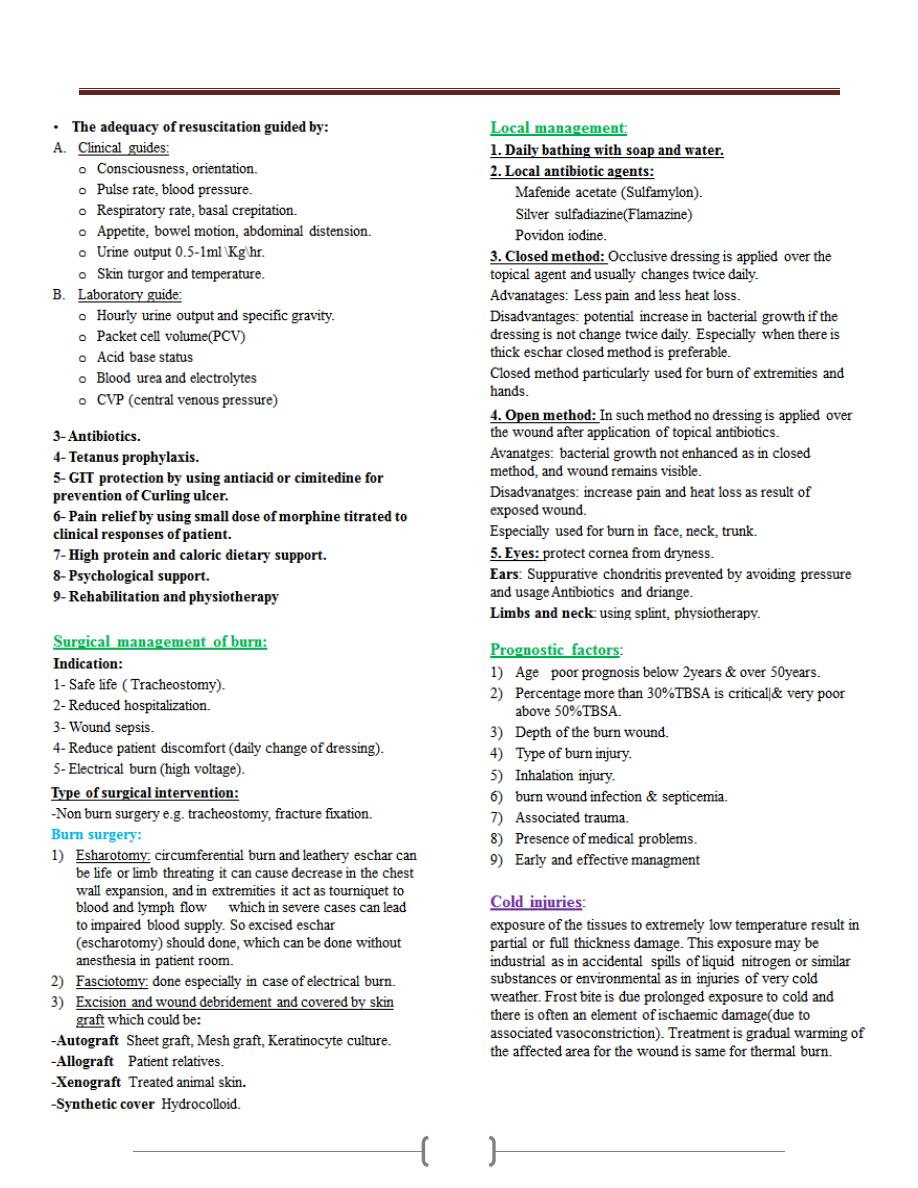

Lecture 12+13 - Burn lecture

52

Lecture 12+13 - Burn lecture

53

Lecture 12+13 - Burn lecture

54

Lecture 12+13 - Burn lecture

55

56

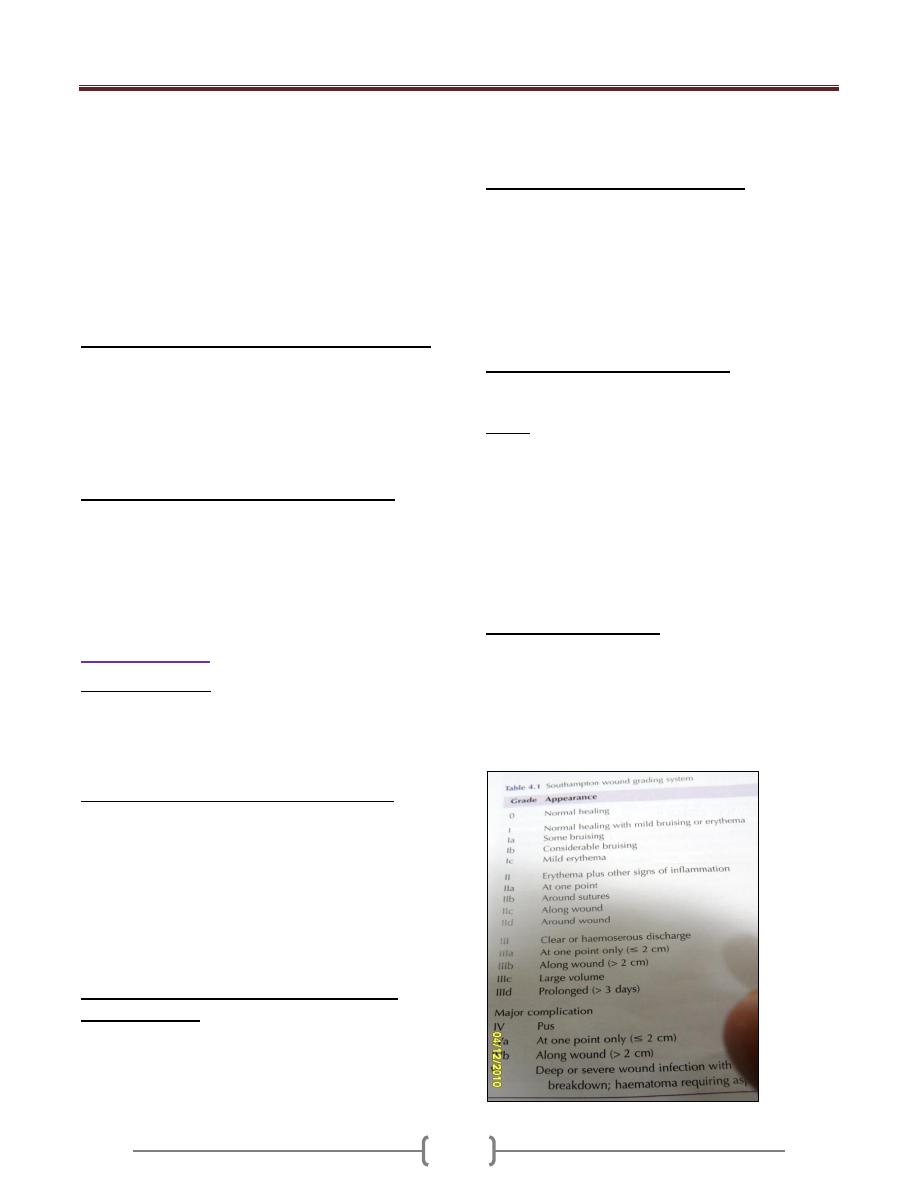

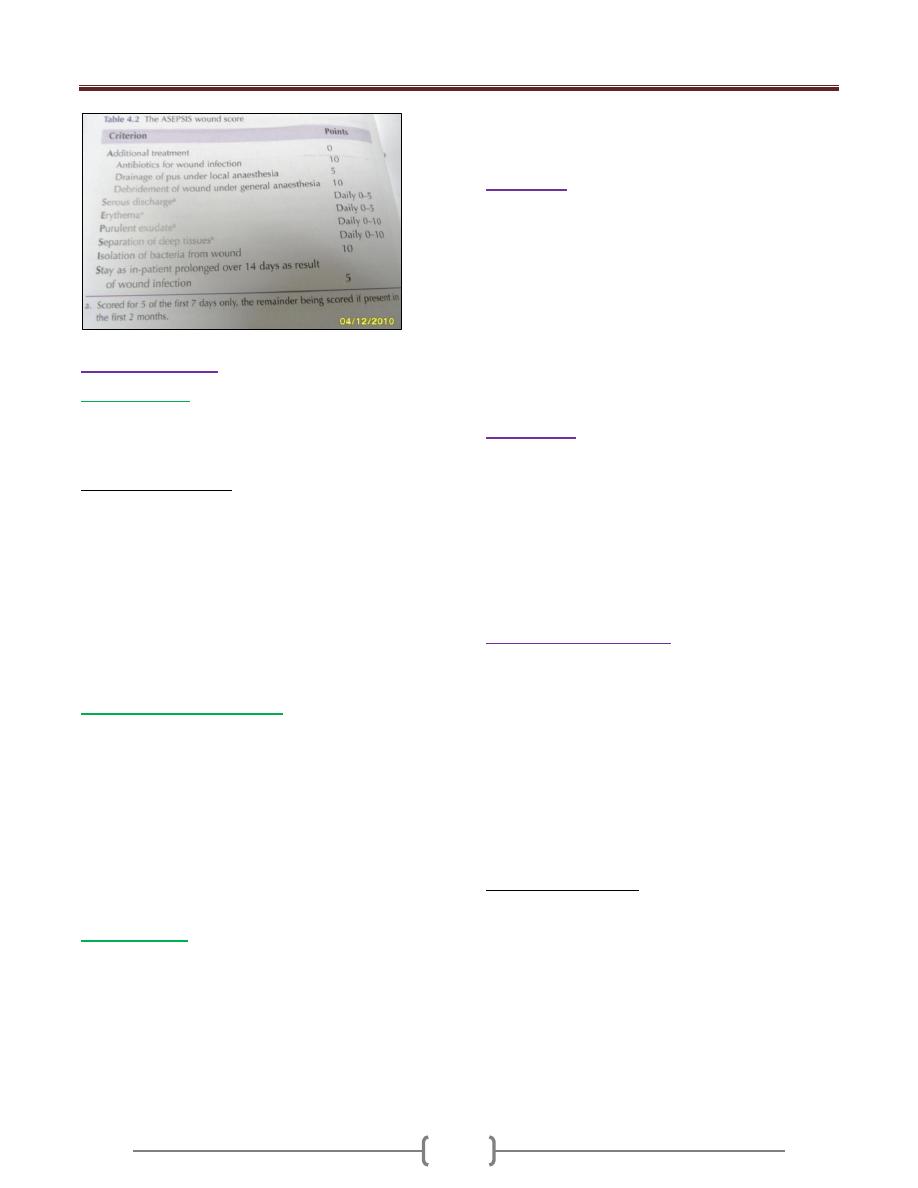

Lecture 1 - Surgical infection

57

Surgical infection has always been a major complication of

surgery& trauma & has been documented for 4000-5000 year

The Egyptians had some concepts about infection as they were

able to prevent putrefaction, testified by mummification skills.

The Hippocratic teaching described the use of anti-

microbials such as wine and vinegar.

Ignac puerperals sepsis could be reduced from over 10% to

under 2% by the simple act of hand-washing between cases

Koch laid down the first definition of infective disease by

microbes.

Koch postulates proving of an infective organism:

It must be found in considerable numbers is the septic

focus

It should be possible to culture it in a pure form from that

septic focus

It should be able to produce similar lesions when injected

into another host

Advances in the control infection in surgery:

1) Aseptic operating theatre techniques have replaced toxic

antiseptic techniques

2) Antibiotics have reduced postoperative infection rates

after elective and emergency surgery

3) Delayed primary, or secondary, closure remains useful in

contaminated.

Wound infection

Protective factors:

1) Intact epithelial surfaces.

2) Chemical.

3) Humeral.

4) Cellular phagocyte, macrophages, W.B.C.

Factors for increase risk of wound infection:

Malnutrition

Obesity

Weight loss (D.M. ,uremia, jundice)

Immunosuppression cancer, AIDS, steroid

Colonisation & translocation in the gastronintestinal tract

Poor perfusion.

F .b. material.

Poor surgical technique.

Factors that determine whether a wound will

become infected:

1) Host response

2) Virulence and inoculum of infected agent

3) Vascularity and health of tissue being invaded

including local ischaemia as well as systemic shock

4) Presence of dead or foreign tissue

5) Presence of antibiotics during the decisive period.

Classification of sources of infection:

Primary: acquired from a community or endogenous

source (such as that following a perforated peptic ulcer)

Secondary or exogenous (HAI): acquired from the

operating theatre (such as inadequate air filtration) or the

ward (e.g. poor hand –washing compliance) or from

contamination at or after surgery (such as an anastomotic

leak).

Local and systemic manifestation :

Infection is invasion of m.o. through tissues foloowing a

breakdown of local and systemic host defences.

Sepsis: is the systemic manifestation of a documented

infection include:

hyperthermia > 38c

Hypothermia <36c

Tachycardia or tachypnia

Increase WBC >12* 10^9/L

Sever sepsis or sepsis syndrom is sepsis with evidence

of one or more organ failure.

Infection may be 1-Endogenous. 2-Exogenous.

Major Wound Infection:

It discharge pus

Systemic manifestation of tachycardia, pyrexia and

increase WBC.

Minor Wound Infection

May discharge pus but should not be associated with

excessive discomfort,systemic signs or delay in return home.

Lecture 1 - Surgical infection

58

Types of infection

1) wound abscess:

It is characterized by heat, redness, pain, swelling, loss of

function.

M.o. is pyogenic staph. Aureus.

Consequence of abscess;

-May discharge spontaneously

1.May need debridment and curretage

2.Chronic abscess,fistula or sinus

3.Perianastomotic abscess.

4.Deep cavity abscess.

The role of antibiotic is controversial unless there is signs

of spreading infection (cellulitis or lymphangitis).

Surgical curretage and decompression must be adequate.

Delayed primary or secondery suture is safer than

primary.

2) Cellulitis and Lymphangitis:

It is non suppurative invasion infection of tissues.

There is sign of inflammation with poor localisation.

M.o. is B. haemolytic streptococcus , staph. Or

c.perfringene.

There is tissue destruction and ulceration.

Systemic signs of toxaemia are common.

Lymphangitis present as painful red streaks in affected

lymphatic and often accompanied by painful lymph node

in the related drainage area.

3) Gas Gangrene:

It is caused by C.perfringens

Usually found in nature ,soil and faeces

Military, traumatic, and colorectal operation.

Wound infection,sever local wound pain and crepitus with

gas in the tissue

Wound appear as thin brown sweet swelling exudate,

oedema, and spreading gangrene, systemic complication,

circulatory collapse and MSOF.

Prophylaxis is with large doses of I.V. penicillin and

debridement of affected tissue.

Treatment:

Suppurative wound infection take 7-10 days

Cellulitis appear in 3-4 days

Major wound infection or cellulitis need antibiotic either

impirical or based on culture and sensitivity

Change of antibiotic lead to resistance.

When wound is under tension and there suppuration so

removal of sutures and evacuation of pus.

In severely contaminated wound ,it is logic to leave the

skin layer open & delayed primary or secondary suture

Sample of pus is taken for culture and sensitivity.

Prophylaxis:

By I.V. antibiotic should be given at induction of

anasthesia when local wound defences are at their least

(decisive period) and before contamination occur.

Ex. Lower limb amputation, patient with known valvular

disease of the heart.

Amoxyl for dental surgery

Second generation cephalosporine for urology

In open viscus surgery metronidazol is added.

Preoperative preparation:

Short preoperative hospital stay

The value of personal hygiene

Shaving should be undertaken immediately before surgery

Scrubbing of operating hands

Skin preparation by hibiscrub ,betadine ,savlyon

Theatre technique

Operator skill in gentle manipulation and dissection with

avoidance of dead space and haematoma.

Similar wound surveillance is needed in postoperative

care.

Major wound infection:

significant quantity of pus

delayed return home

patient are systemically ill

Lecture 2+3 – Cyst, Ulcer, sinuses & Fistulas

59

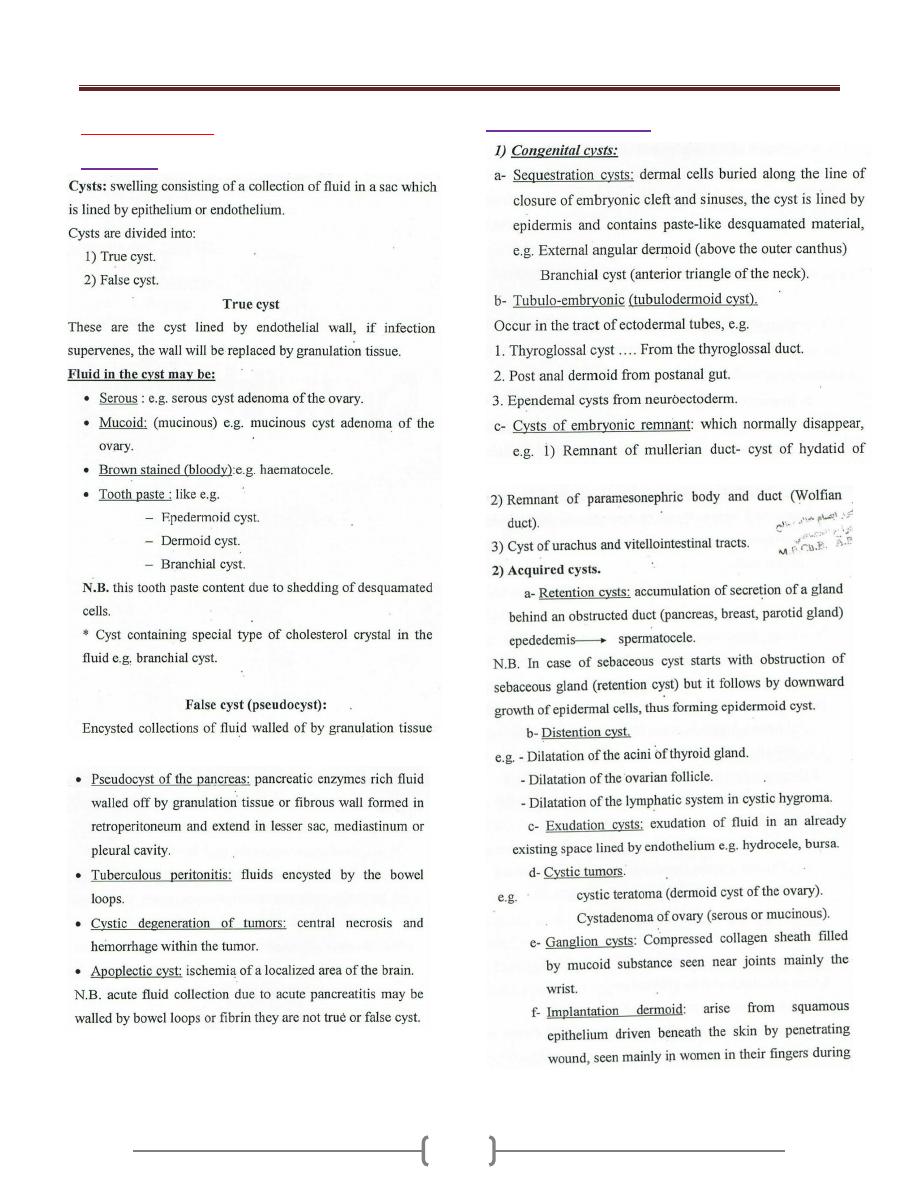

Cysts (bladder)

Definition

Classification of cysts

Lecture 2+3 – Cyst, Ulcer, sinuses & Fistulas

60

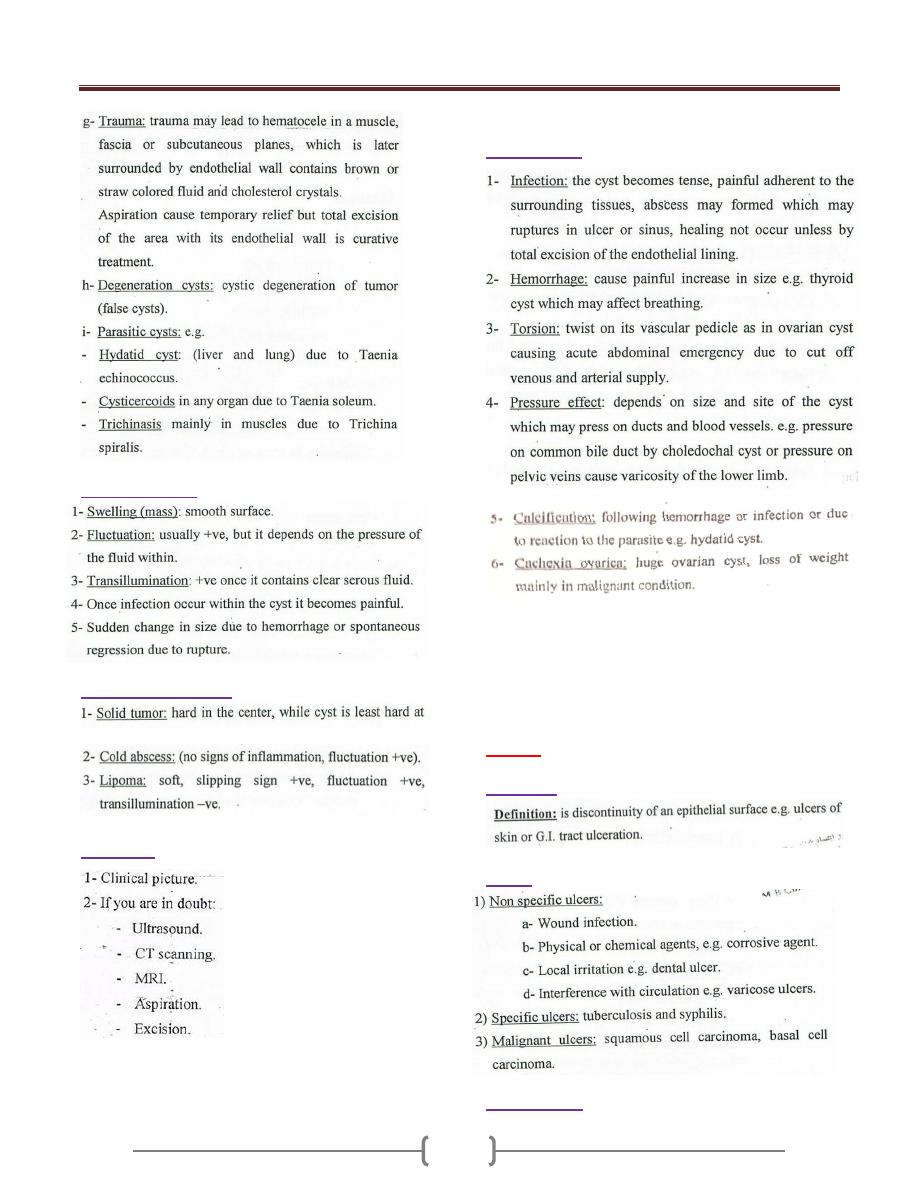

Clinical features

Differential diagnosis

Diagnosis

Complication

Ulcers

Definition

Types

Trophic ulcer

Lecture 2+3 – Cyst, Ulcer, sinuses & Fistulas

61

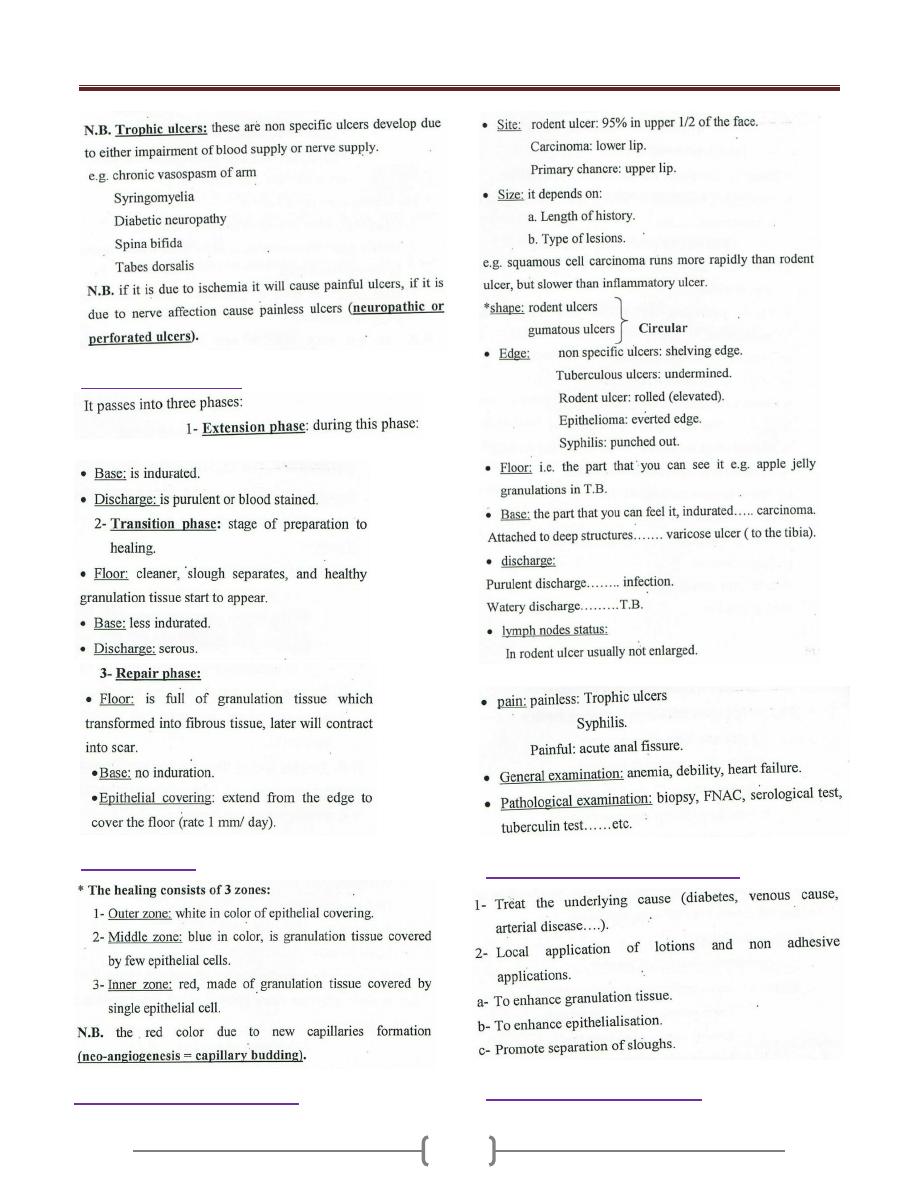

Life history of an ulcer

Zones of healing

Clinical examination of an ulcer

Local treatment of nonspecific ulcer

The ideal dressing should have

Lecture 2+3 – Cyst, Ulcer, sinuses & Fistulas

62

Antiseptic and topical antibodies

Wound dressing

Sinuses & Fistulas

Sinuses

Fistula

Causes of persistence of Fistulas & Sinuses

Treatment

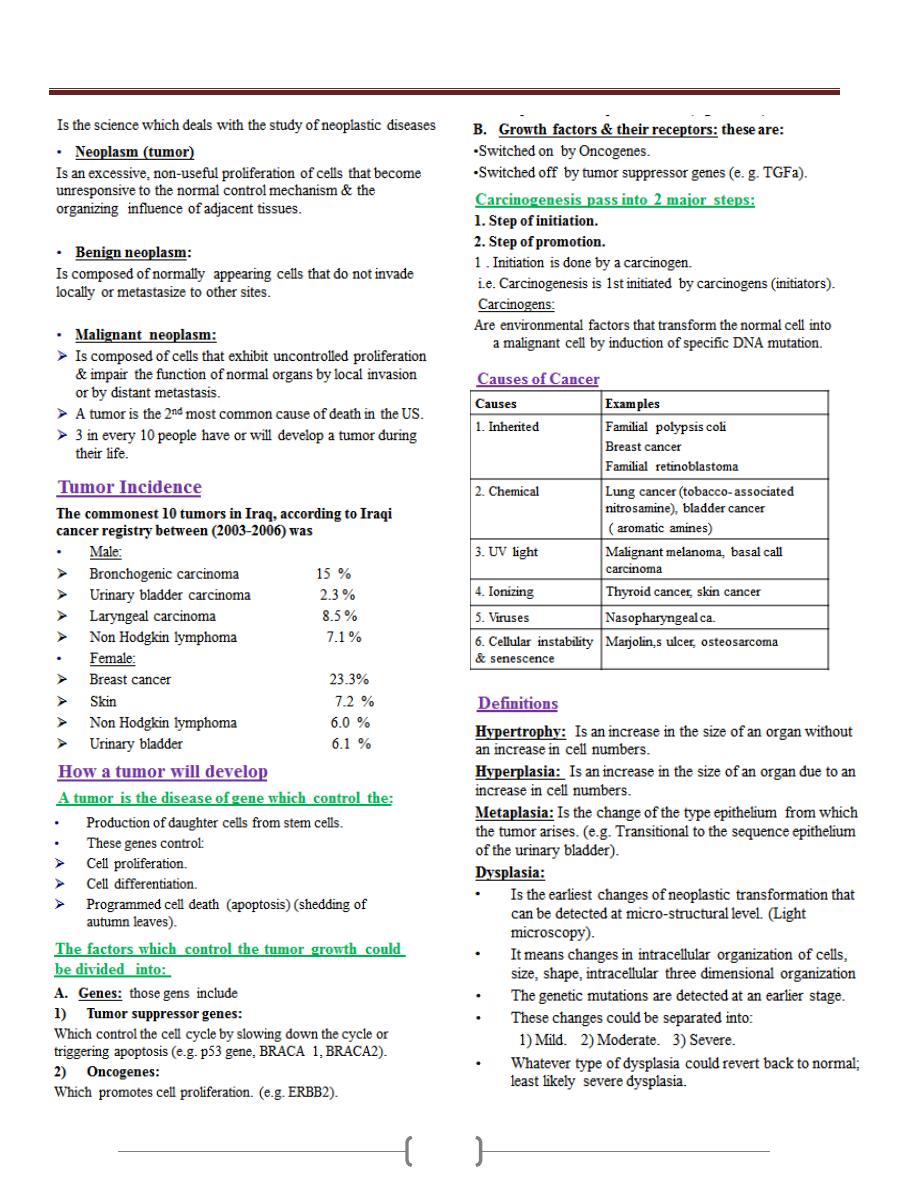

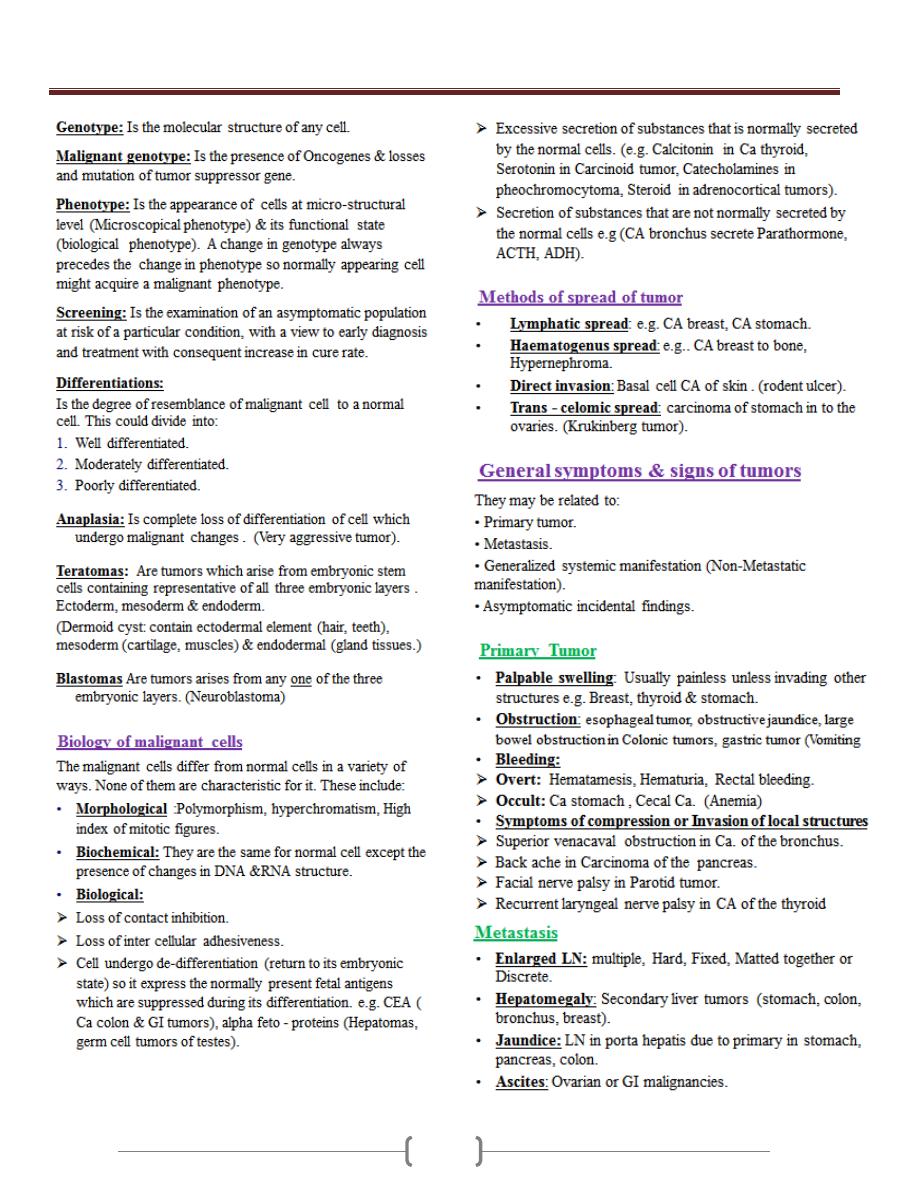

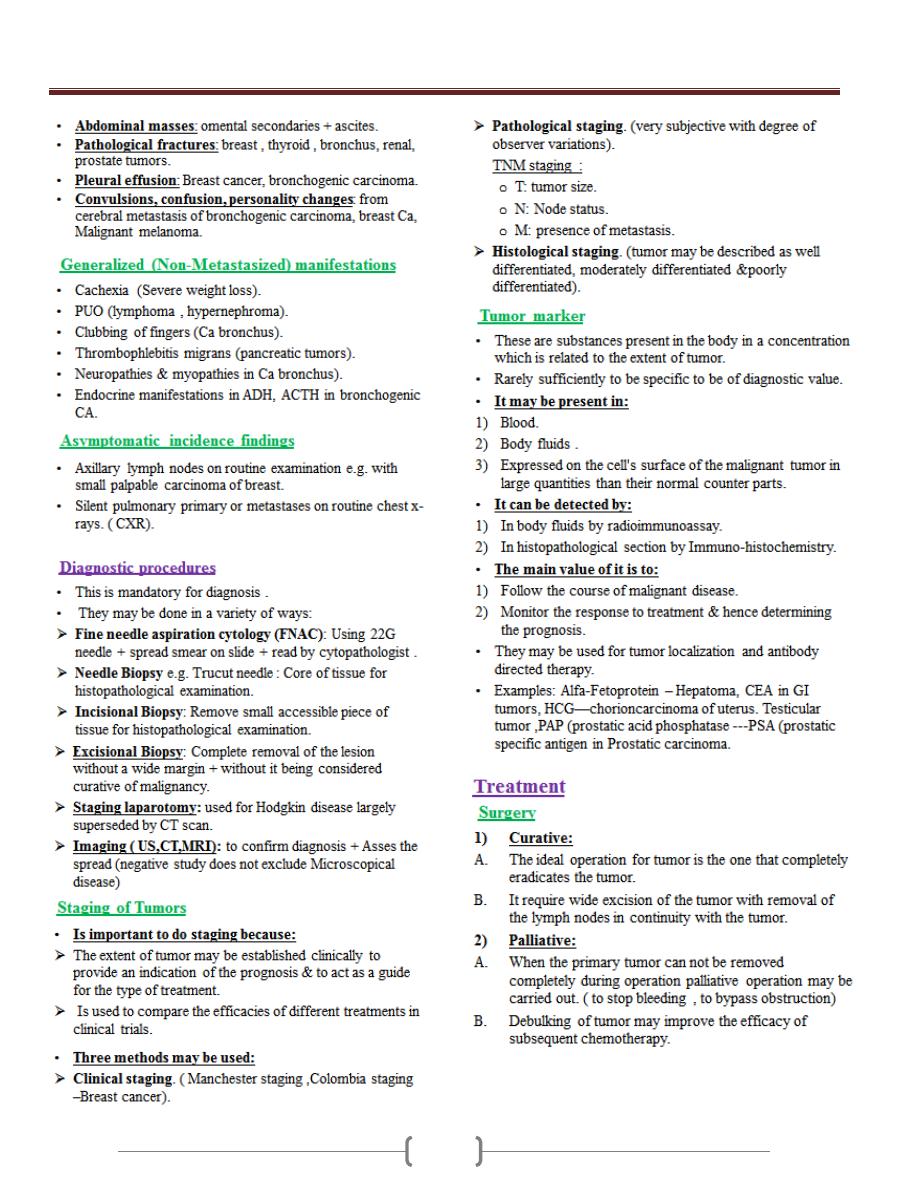

Lecture 4+5+6 - Oncology

63

Lecture 4+5+6 - Oncology

64

Lecture 4+5+6 - Oncology

65

Lecture 4+5+6 - Oncology

66

Lecture 7+8 – Artificial nutritional support

67

Lecture 7+8 – Artificial nutritional support

68

Lecture 7+8 – Artificial nutritional support

69

Lecture 7+8 – Artificial nutritional support

70

Lecture 7+8 – Artificial nutritional support

71

Lecture 7+8 – Artificial nutritional support

72

Lecture 7+8 – Artificial nutritional support

73

Lecture 7+8 – Artificial nutritional support

74

Lecture 7+8 – Artificial nutritional support

75

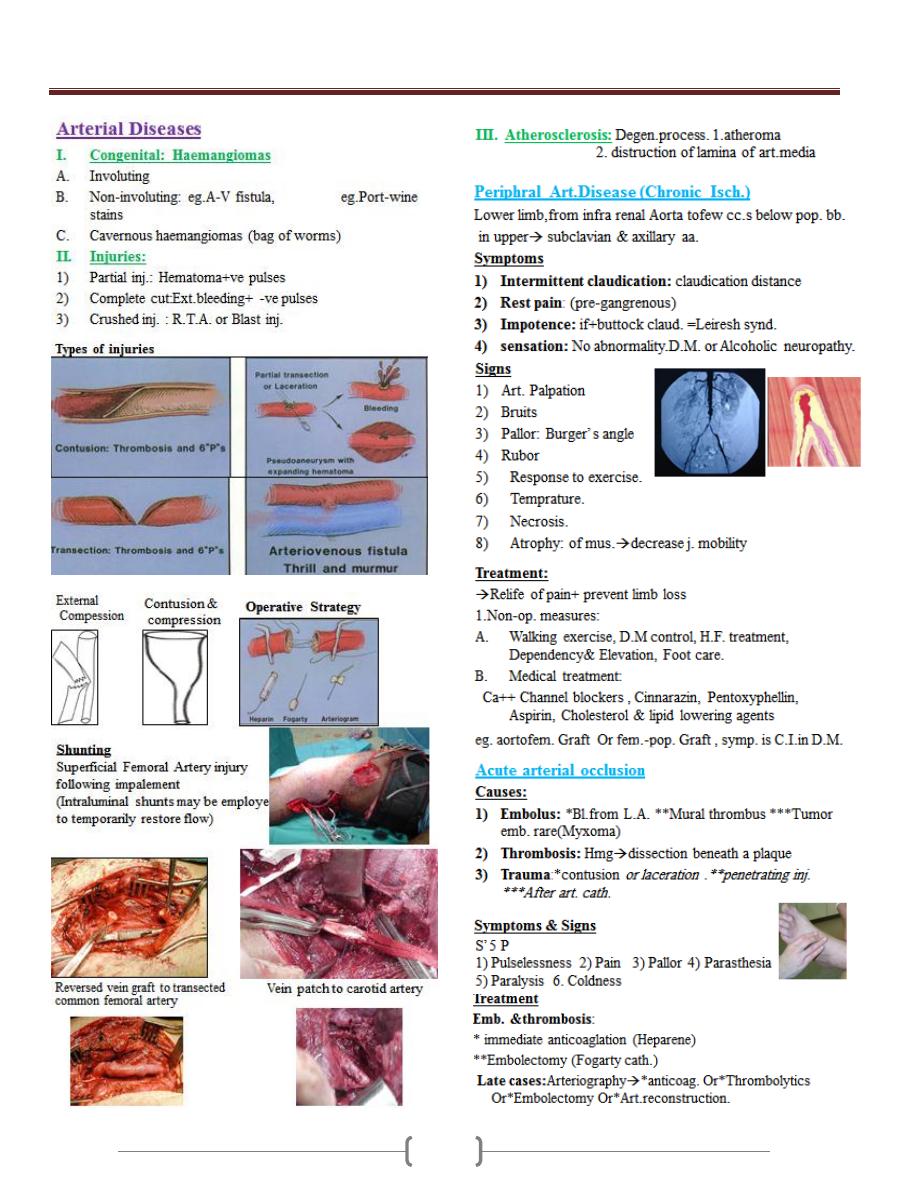

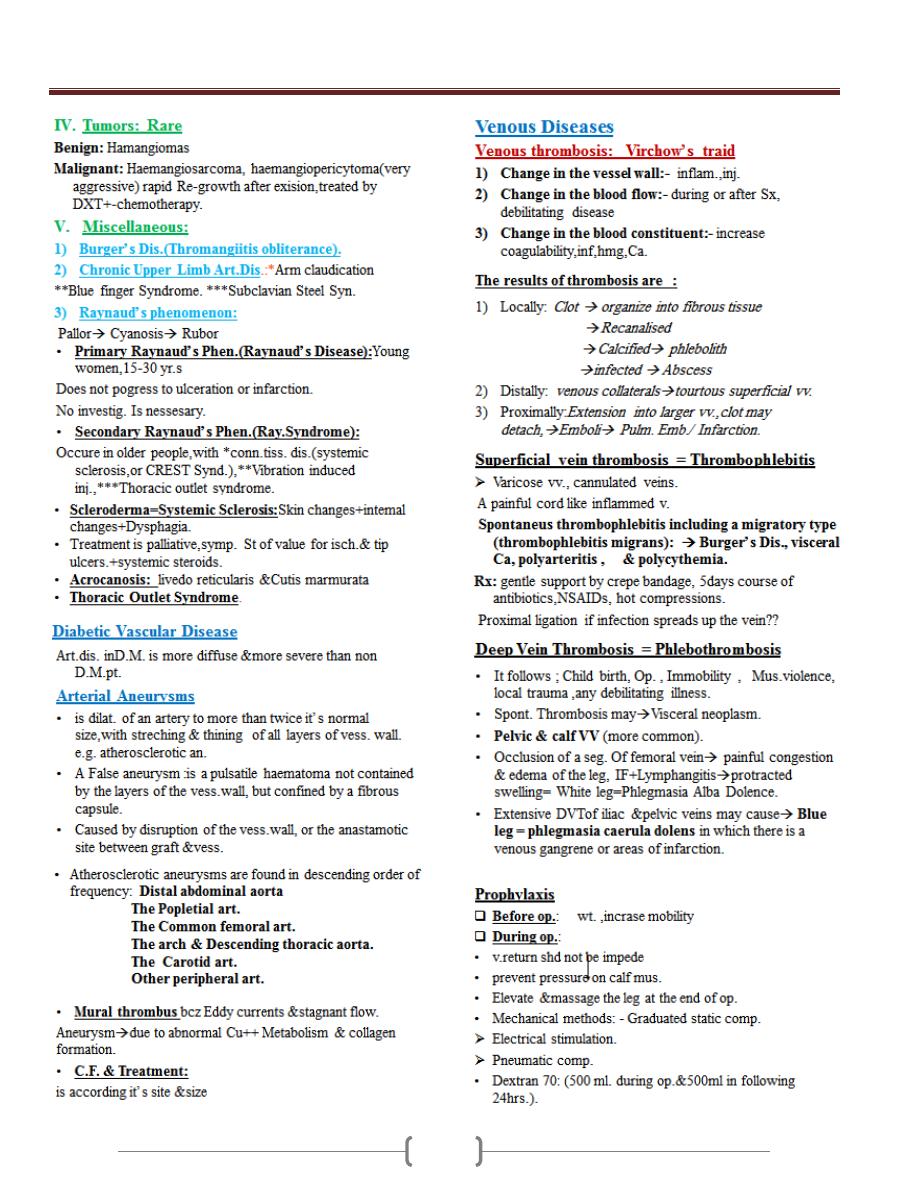

Lecture 9 - Vascular Surgery

76

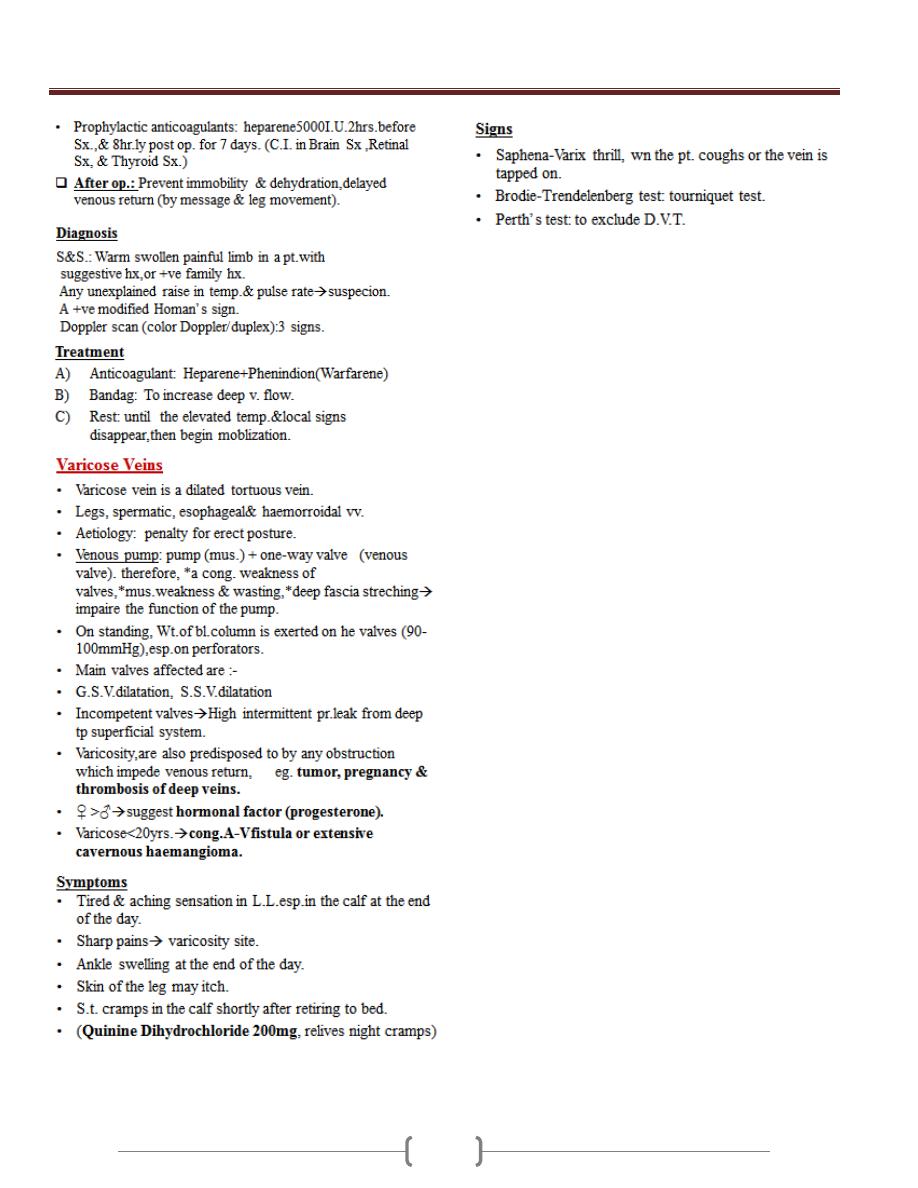

Lecture 9 - Vascular Surgery

77

Lecture 9 - Vascular Surgery

78