AFTER MID

SURGERY

DR. ALI BAQER

Orthopaedic

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

(DDH)

LECTURES 4

Dr. Ali BaQer

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip(DDH) & Coxa Vara

DR. Ali Bakir Al-Hilli

Assist. Professor

Fellowship, Pediatric & Spine Orthopedic/USA

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip(DDH)

The term ‘congenital dislocation of the hip’ (CDH) hasbeen largely superseded by

developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) in an attempt to describe the rangeand

evolution of abnormalities that occur in this condition.This comprises a spectrum of

disorders including acetabular dysplasia without displacement, subluxation and

dislocation.

Normal hip development depends on proportionate growth of the acetabular tri-radiate

cartilages and the presence of a concentrically located femoral head. Whether the

instability comes first and then affects acetabular development because of imperfect

seating of the femoral head, or is a result of a primary acetabular dysplasia, is still

uncertain. Both mechanisms might be important.

The reported incidence of neonatal hip instability in northern Europe is approximately 1

per 1000 live Births.

Girls are much more commonly affected, 7:1.

The left hip is more often affected than the right; in 1 in 5 cases the condition is bilateral.

Aetiology and pathogenesis

Genetic factors

* generalized joint laxity (adominant trait), and *shallow acetabula (a polygenic trait

which is seen mainly in girls and their mothers).

Hormonal factors

(e.g. high levels of maternal oestrogen, progesterone and relaxin in the last few weeks

of pregnancy).

Intrauterine malposition

(especially a breech position with extended legs) ‘packaging disorder’ .

Postnatal factors

After weight-bearing commences, these changes are intensified. Both the acetabulum

and the femoral neck remain anteverted and the pressure of the femoral head induces a

false socket to form above the shallow acetabulum.

Clinical features

The ideal is to diagnose every case at birth.

*For this reason, every newborn child should be examined for signs of hip instability.

*Where there is a family history of congenital instability, and with breech presentations

or signs of other congenital abnormalities, extra care is taken and the infant may have

to be examined more than once.

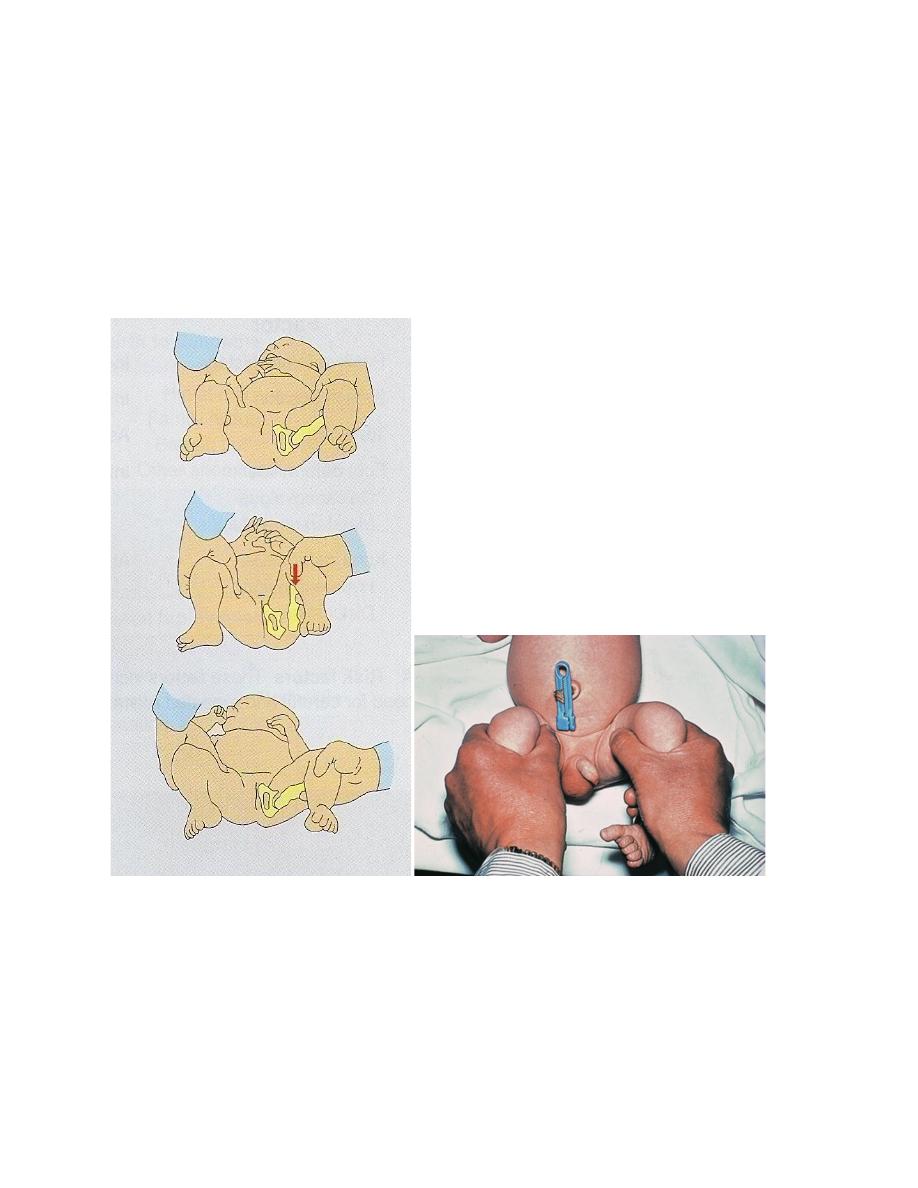

In Ortolani’s test, the baby’s thighs are held with the thumbs medially and the fingers

resting on the greater trochanters; the hips are flexed to 90 degrees and gently

abducted. Normally there is smooth abduction to almost 90 degrees. In congenital

dislocation the movement is usually impeded, but if pressure is applied to the greater

trochanter there is a soft ‘clunk’ as the dislocation reduces, and then the hip abducts

fully (the ‘jerk of entry’).

Barlow’s test is performed in a similar manner, but here the examiner’s thumb is

placed in the groin and, by grasping the upper thigh, an attempt is made to lever the

femoral head in and out of the acetabulum during abduction and adduction. If the

femoral head is normally in the reduced position, but can be made to slip out of the

socket and back in again, the hip is classed as ‘dislocatable’ (i.e. unstable).

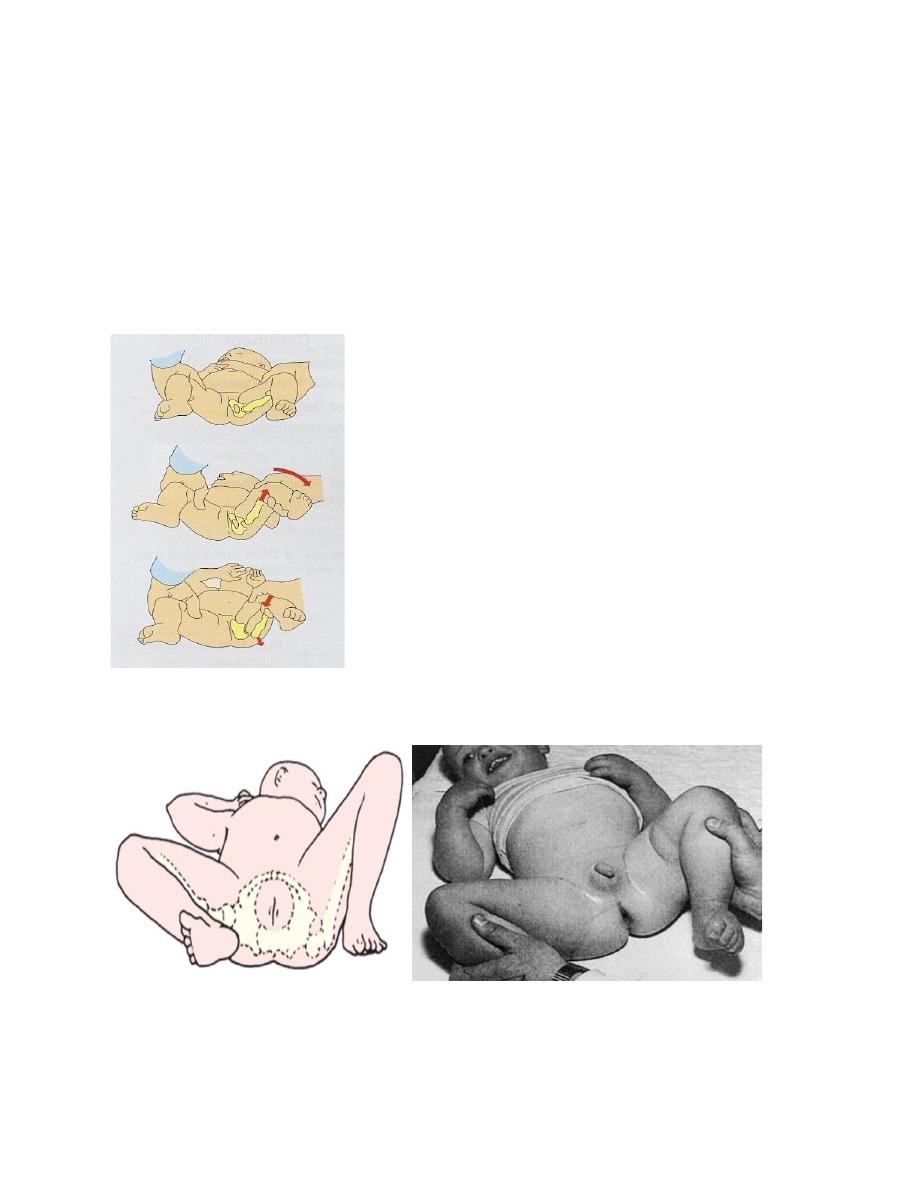

Late features An observant mother may spot asymmetry,a clicking hip, or difficulty in

applying the napkin (diaper) because of limited abduction.

With unilateral dislocation the skin creases look asymmetrical and the leg is slightly

short (Galeazzi’s sign) and externally rotated; a thumb in the groin may feel that the

femoral head is missing.

With bilateral dislocation there is an abnormally wide perineal gap.Abduction is

decreased.

*Contrary to popular belief, late walking is not a marked feature; nevertheless, in

children who do not walk by 18 months dislocation must be excluded. Likewise, a limp

or Trendelenburg gait, or a waddling gait could be a sign of missed dislocation.

Imaging

Ultrasound scanning has replaced radiography for imaging hips in the newborn. The

radiographically ‘invisible’ acetabulum and femoral head can, with practice, be displayed

with static and dynamic ultrasound. Sequential assessment is straightforward and

allows monitoring of the hip during a period of splintage.

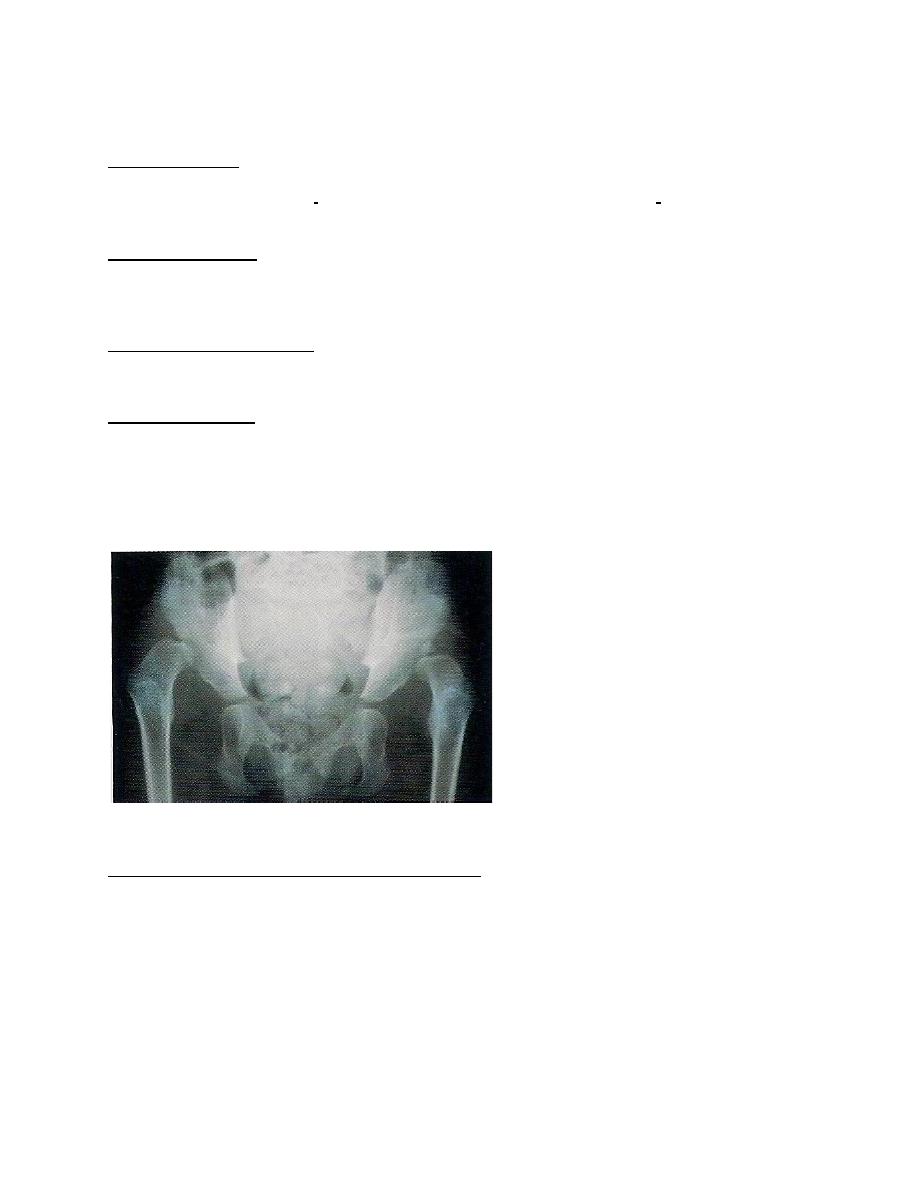

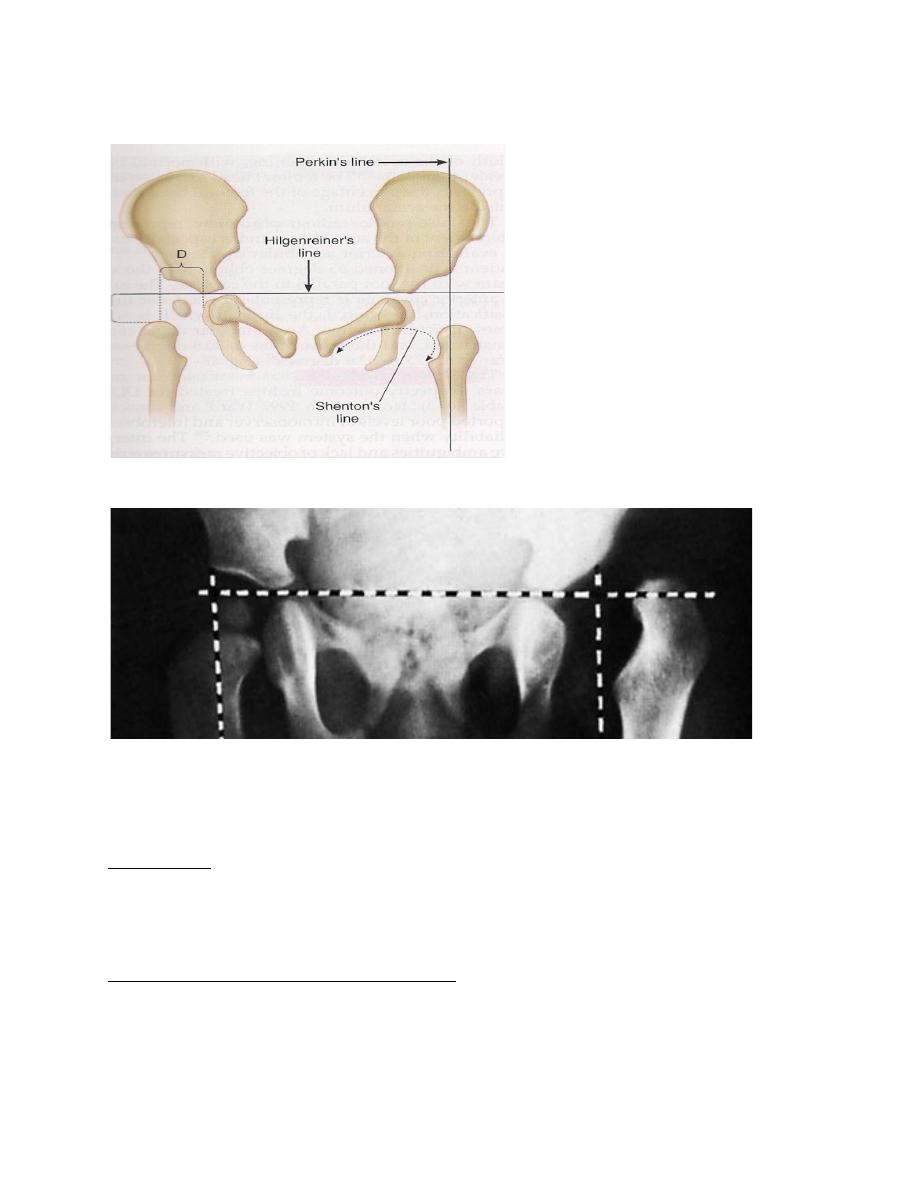

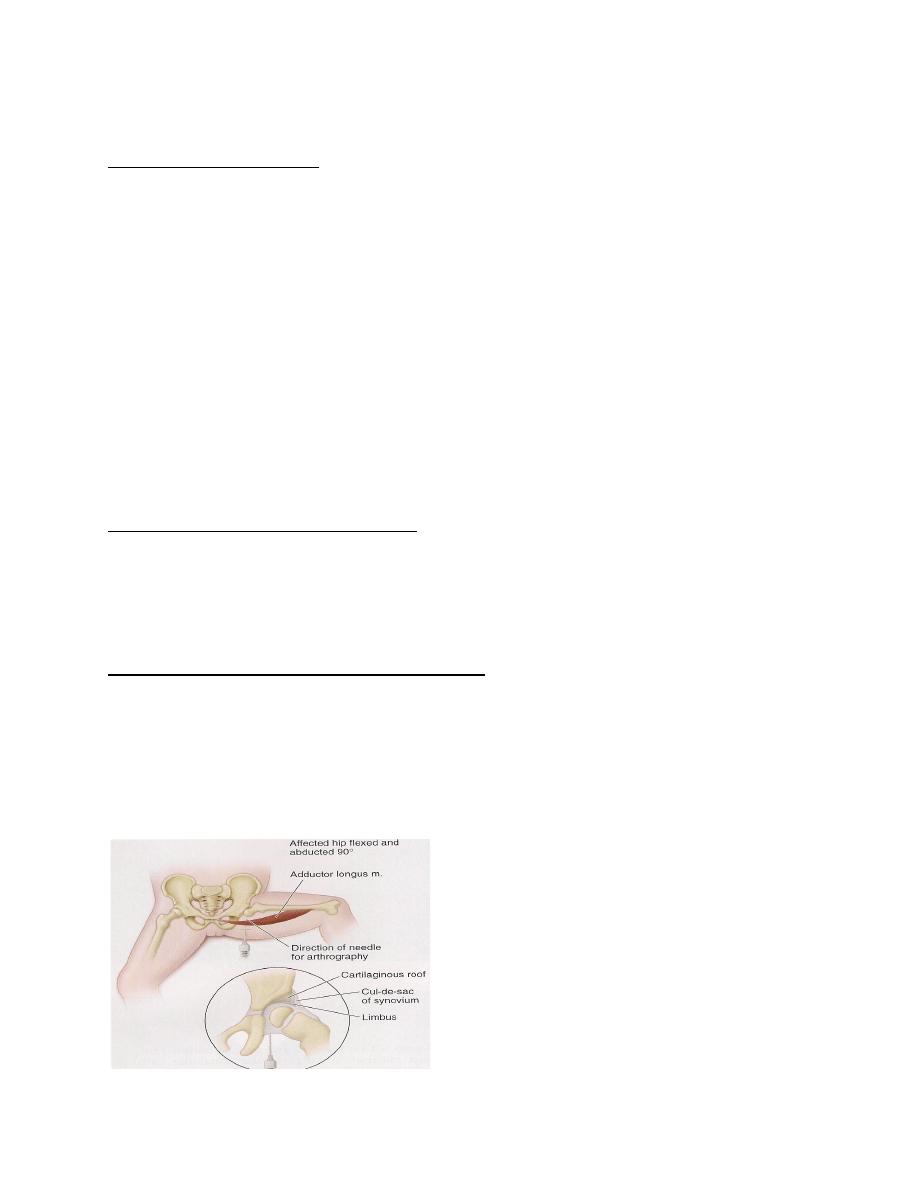

Plain x-rays: X-rays of infants are difficult to interpret and in the newborn they can be

frankly misleading. This is because the acetabulum and femoral head are largely (or

entirely) cartilaginous and therefore not visible on x-ray. X-ray examination is more

useful after the first 6 months, and assessment is helped by drawing

lines on the x-ray plate to define three geometric indices.

Perkins’ line & Hilgenreiner’s line

Screening

Neonatal screening in dedicated centers has led to a marked reduction in missed

cases of DDH.

Risk factors

family history, breech presentation, oligohydramnios and the presence of other

congenital abnormalities are taken into account in selecting newborn infants for special

examination and ultrasonography.

Ideally all neonates should be examined.

Management

THE FIRST 3–6 MONTHS

Where facilities for ultrasound scanning are available, all newborn infants with a high-

risk background or a suggestion of hip instability are examined by ultrasonography.

*If ultrasound is not available, the simplest policy is to regard all infants with a high-risk

background or a positive Ortolani or Barlow test, as ‘suspect’ and to nurse them in

double napkins or an abduction pillow for the first 6 weeks. *At that stage they are re

examined:

those with stable hips are left free but kept under observation for at least 6 months;

those with persistent instability are treated by more formal abduction Splintage until the

hip is stable and x-ray shows that the acetabular roof is developing satisfactorily

(usually 3–6 months)

Splintage The object of splintage is to hold the hips somewhat flexed and abducted;

extreme positions are avoided and the joints should be allowed some movement in the

splint.

The three golden rules of splintage are:

(1)the hip must be properly reduced before it is splinted.

(2) extreme positions must be avoided.

(3) the hips should be able to move.

PERSISTENT DISLOCATION: 6–18 MONTHS

If the hip is still incompletely reduced, or if the child presents late with a ‘missed’

dislocation, the hip must be reduced by closed methods or operation, and held reduced

until acetabular development is satisfactory.

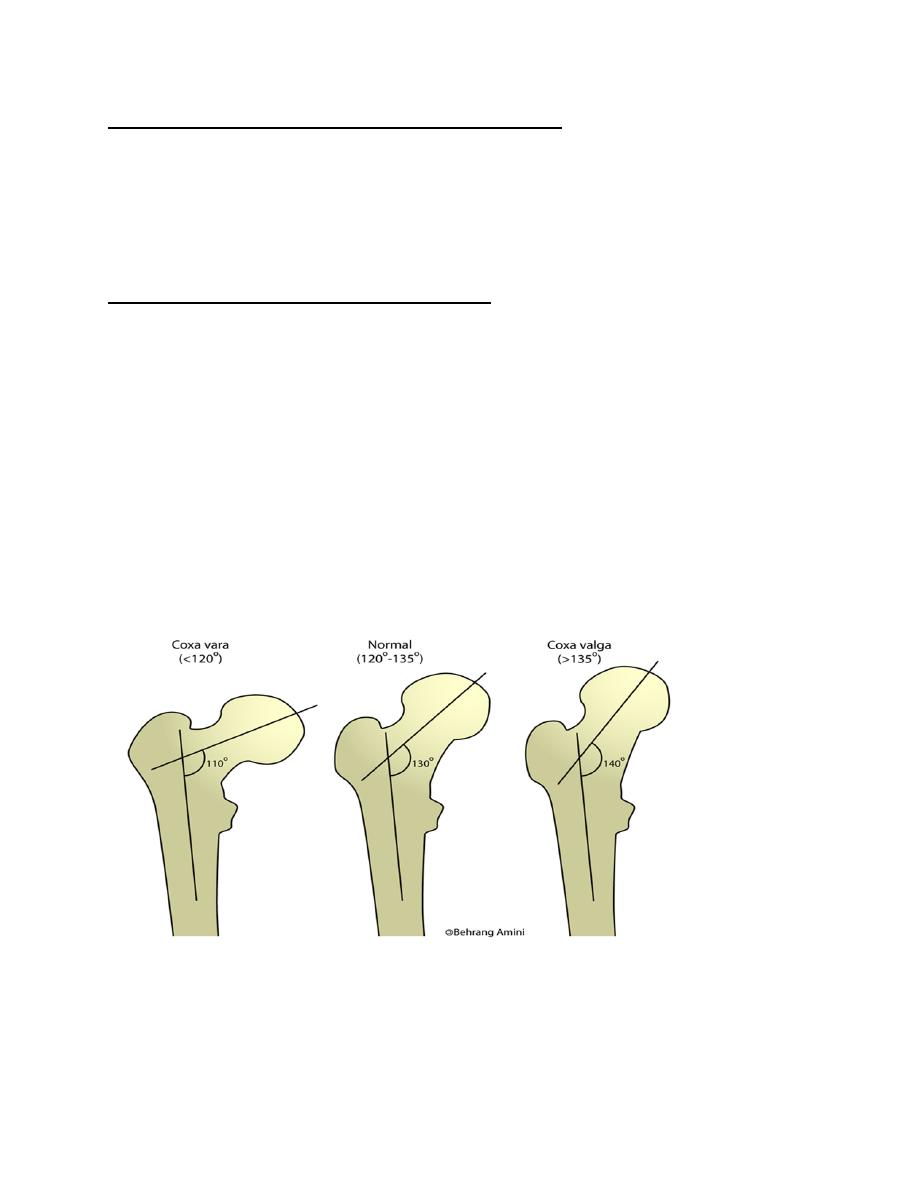

Closed reduction is suitable after the age of 3 months.

General anaesthesia with an arthrogram to confirm a concentric reduction.

PERSISTENT DISLOCATION: 18 MONTHS – 4 YEARS

In the older child, closed reduction is less likely to succeed; many surgeons would

proceed straight to arthrography and open reduction. *Traction Even if closed

reduction is unsuccessful (if necessary combined with psoas and adductor tenotomy)

may help to loosen the tissues and bring the femoral head down opposite the

acetabulum. An arthrogram at this stage will clarify the anatomy of the hip and show

whether there is an inturned limbus or any marked degree of acetabular dysplasia.

DISLOCATION IN CHILDREN OVER 4 YEARS

Reduction and stabilization become increasingly difficult. Nevertheless, in children

between 4 and 8 years – especially if the dislocation is unilateral – it is still worth

attempting, bearing in mind that the risk of avascular necrosis and hip stiffness

With bilateral dislocation the deformity and the waddling gait is symmetrical and

therefore not so noticeable; the risk of operative intervention is also greater because

failure on one or other side turns this into an asymmetrical deformity. Therefore, avoid

operation above the age of 6 years. The untreated patient walks with a waddle but may

be surprisingly uncomplaining.

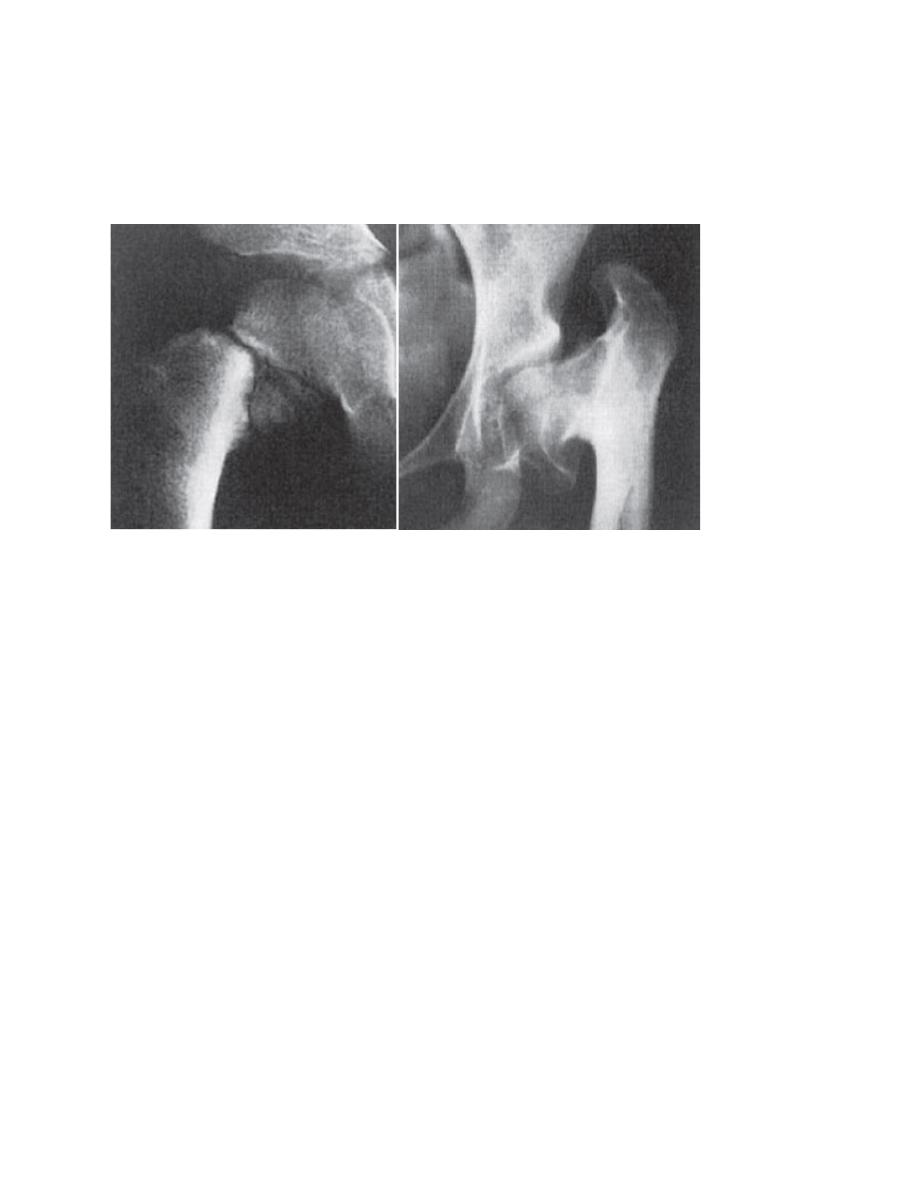

COXA VARA

The normal femoral neck–shaft angle is 160 degrees. at birth, decreasing to 125

degrees in adult life. less than 120 degrees is called coxa vara. Congenital or

Acquired.

CONGENITAL COXA VARA

It is due to a defect of endochondral ossification in the medial part of the femoral neck.

When the child starts to crawl or stand, the femoral neck bends, and with continued

Weight bearing it collapses increasingly.

Clinical features

*The condition is usually diagnosed when the child starts to walk.

*The leg is short and the thigh may be bowed.

*X-rays show that the femoral neck is in varus and abnormally short.

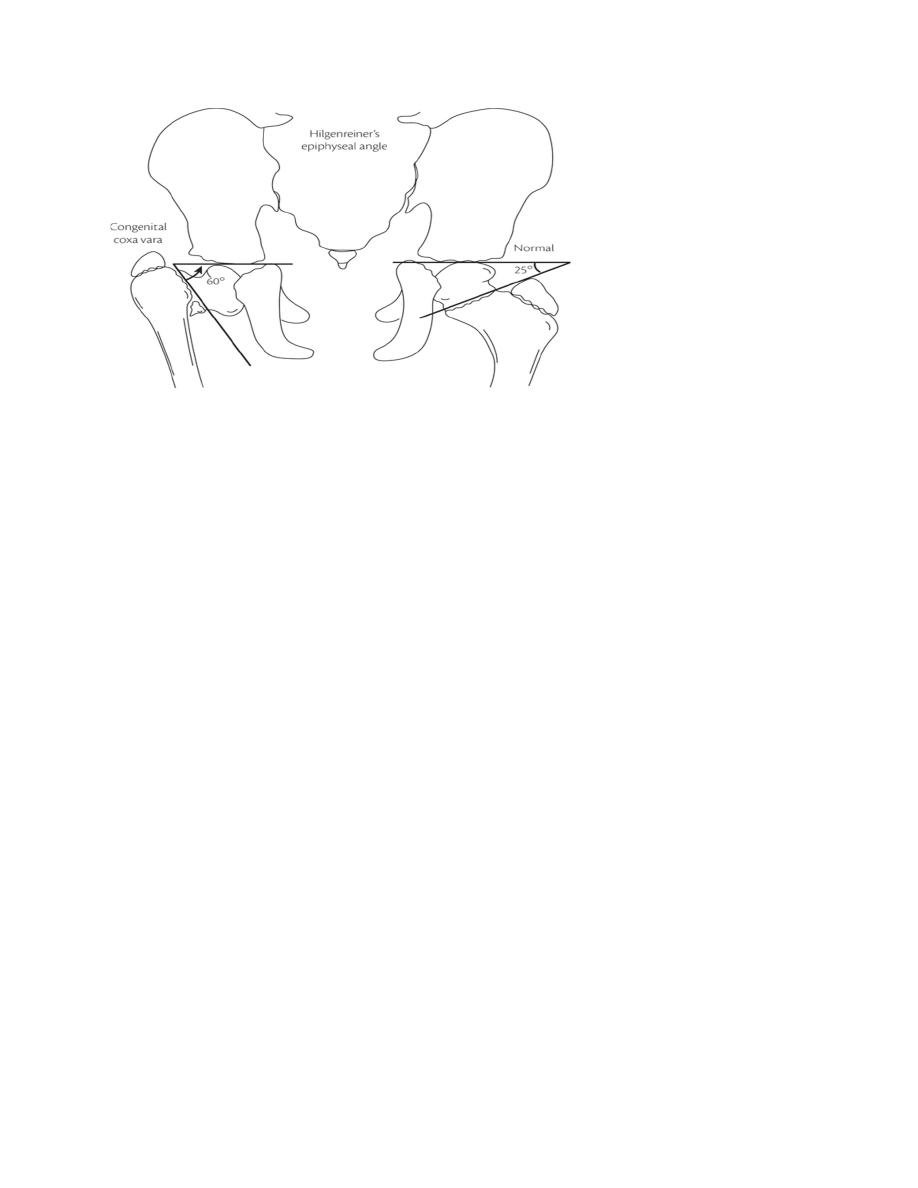

* A helpful alternative is to measure Hilgenreiner’s epiphyseal angle – the angle

subtended by a horizontal line joining the centre (triradiate cartilage) of each hip and

another parallel to the physeal line; the normal angle is about 30 degrees

. *At maturity the deformity may be quite bizarre.

Treatment

*If the epiphyseal angle is 40- 60 degrees, the child should be kept under observation

and re-examined at intervals for signs of progression.

*If it is more than 60 degrees, or if shortening is progressive, the deformity should be

corrected by a subtrochanteric or intertrochanteric valgus osteotomy.

Done by : Murtedha Abbas