1

Lectures In the

Internal medicine

LEC(4&5&6)

Dr.Dhaher JS Al-habbo

FRCP London UK

Assistant Professor in Medicine

DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE

2

4th stage

باطنية

Lec-4

د.ظاهر

8/11/2015

Tuberculosis (TB)

Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis

(MTB), which is part of a complex of organisms including M. bovis (reservoir

cattle) and M. africanum (reservoir human).

With1.5 million deaths attributable to TB.

One-third of the world's population has latent TB.

The majority of cases occur in the world's poorest nations.

The resurgence of TB has been largely driven in Africa by HIV disease, and

in the former Soviet Union and Baltic states by lack of appropriate health

care exacerbated by social and political upheaval.

Tuberculosis (TB)

• Tuberculosis (TB) is caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis

(MTB), M. tuberculosis is spread by the inhalation of

aerosolised droplet nuclei from other infected

patients.

• Once inhaled, the organisms lodge in the alveoli and initiate the

recruitment of macrophages and lymphocytes.

• Macrophages undergo transformation into epithelioid and Langhans cells

which aggregate with the lymphocytes to form the classical tuberculous

granuloma .

• M. bovis infection arises from drinking non-sterilised milk from infected

cows.

3

Tuberculosis (TB)

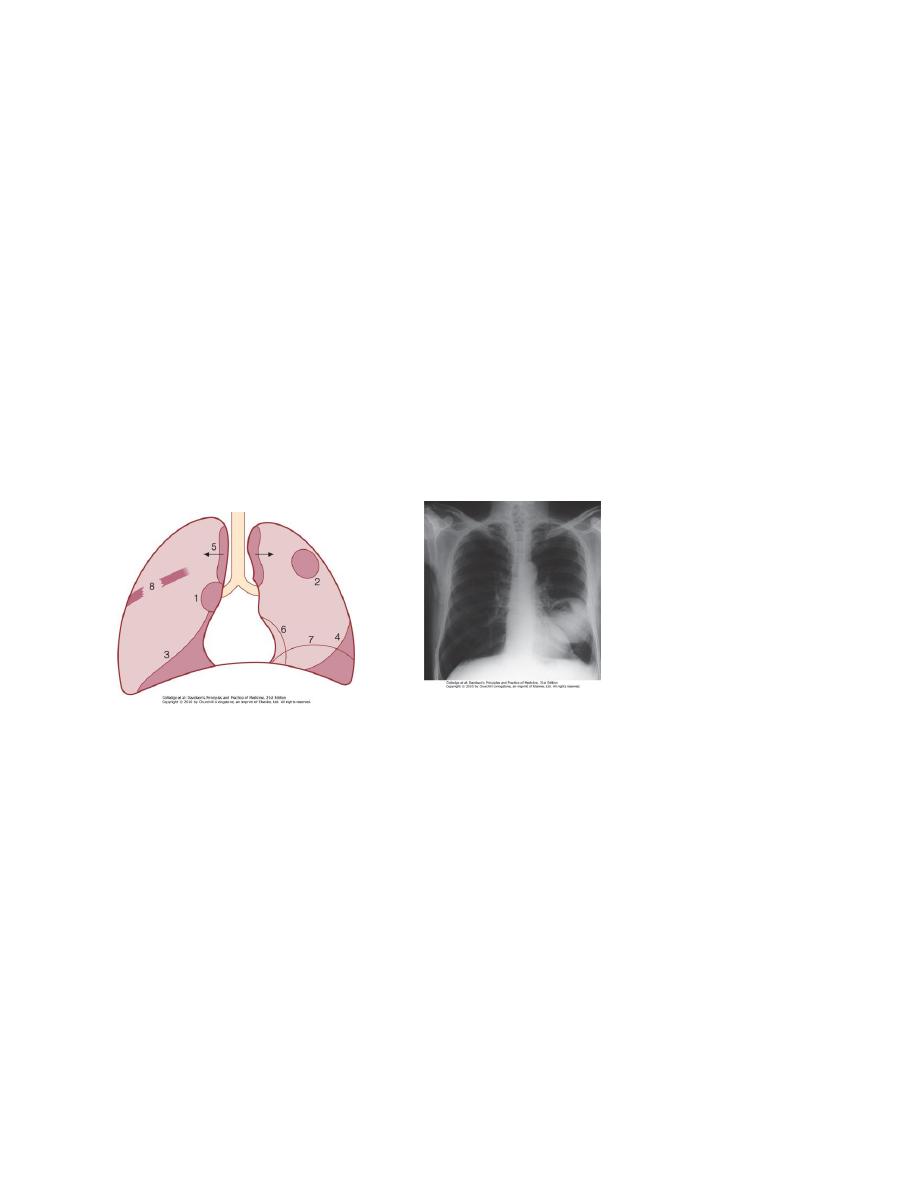

Numerous granulomas aggregate to form a primary lesion or 'Ghon focus' ,which

is characteristically situated in the periphery of the lung.

Also spread of organisms to the hilar lymph nodes is followed by 'Ghon focus

reaction;

Combination of a primary lesion and regional lymph nodes is referred to as the

'primary complex of Ranke'.

Reparative processes encase the primary complex in a fibrous capsule limiting the

spread of bacilli: so-called latent TB.

If no further complications ensue, this lesion eventually calcifies and is clearly

seen on a chest X-ray

Factors increasing the risk of TB

Patient-related

Age (children > young adults < elderly) ,Close contacts of patients with

smear-positive pulmonary TB ,Overcrowding,

Chest radiographic evidence of self-healed TB , Smoking: cigarettes

Primary infection < 1 year previously

Associated diseases

Immunosuppression: HIV, anti-TNF therapy, high-dose corticosteroids,

cytotoxic agents

Malignancy (especially lymphoma and leukaemia)

Type 1 diabetes mellitus ,Chronic renal failure ,Silicosis

Gastrectomy, jejuno-ileal bypass, cancer of the pancreas, malabsorption.

4

Deficiency of vitamin D or A

• Recent measles: increases risk of child contracting TB

Timetable of TB

Time from

infection

Primary complex, positive tuberculin skin test

3-8 weeks

Meningeal, miliary and pleural disease

3-6 months

Gastrointestinal, bone and joint, and lymph

node disease

Up to 3 years

Renal tract disease

Around 8 years

Post-primary disease due to reactivation or

reinfection

From 3 years

onwards

Features of primary TB infection(4-8weeks)

• Influenza-like illness.

• Skin-test conversion.

• Primary complex.

Hypersensitivity .

Erythema nodosum.

Phlyctenular conjunctivitis .

Dactylitis

5

Primary TB

Primary TB refers to the infection of a previously uninfected (tuberculin-negative)

individual.

A few patients develop a self-limiting febrile illness but clinical disease only occurs

if there is a hypersensitivity reaction or progressive infection .

Progressive primary disease may appear during the course of the initial illness or

after a latent period of weeks or months.

Miliary TB

• Blood-borne dissemination gives rise to miliary TB, which may present

acutely but more frequently is characterised by 2-3 weeks of fever, night

sweats, anorexia, weight loss and a dry cough.

• Hepatosplenomegaly may develop and the presence of a headache may

indicate coexistent tuberculous meningitis.

• Auscultation of the chest is frequently normal, although with more

advanced disease widespread crackles are evident. Fundoscopy may show

choroidal tubercles.

• The classical appearances on chest X-ray are of fine 1-2 mm lesions ('millet

seed') distributed throughout the lung fields, although occasionally the

appearances are coarser.

• Anaemia and leucopenia reflect bone marrow involvement. 'Cryptic'

miliary TB is an unusual presentation sometimes seen in old age

Post-primary pulmonary TB

Cryptic M. TB

• Age over 60 years

• Intermittent low-grade pyrexia of unknown origin

6

• Unexplained weight loss, general debility (hepatosplenomegaly in 25-50%)

• Normal chest X-ray

• Blood dyscrasias; leukaemoid reaction, pancytopenia

• Negative tuberculin skin test

• Confirmation by biopsy (granulomas and/or acid-fast bacilli demonstrated)

of liver or bone marrow

Post-primary pulmonary TB

Clinical presentations of pulmonary TB

• Chronic cough, often with haemoptysis

• Pyrexia of unknown origin

• Unresolved pneumonia

• Exudative pleural effusion

• Asymptomatic (diagnosis on chest X-ray)

• Weight loss, general debility

• Spontaneous pneumothorax

Post-primary pulmonary TB

• Post-primary disease refers to exogenous ('new' infection) or endogenous

(reactivation of a dormant primary lesion) infection in a person who has

been sensitised by earlier exposure.

• It is most frequently pulmonary and characteristically occurs in the apex of

an upper lobe where the oxygen tension favours survival of the strictly

aerobic organism.

• The onset is usually insidious, developing slowly over several weeks.

7

• Systemic symptoms include fever, night sweats, malaise, and loss of

appetite and weight, and are accompanied by progressive pulmonary

symptoms .

• Very occasionally, this form of TB may present with one of the

complications of TB.

Post-primary pulmonary TB

Radiological changes include ill-defined opacification in one or both of the upper

lobes, and as progression occurs, consolidation, collapse and cavitation develop

to varying degrees .

It is often difficult to distinguish active from quiescent disease on radiological

criteria alone, but the presence of a miliary pattern or cavitation favours active

disease.

In extensive disease, collapse may be marked and result in significant

displacement of the trachea and mediastinum.

Occasionally, a caseous lymph node may drain into an adjoining bronchus

resulting in tuberculous pneumonia.

Clinical features: extrapulmonary disease

Pulmonary

• Massive haemoptysis

• Cor pulmonale

• Fibrosis/emphysema

• Atypical mycobacterial infection

• Aspergilloma

• Lung/pleural calcification

• Obstructive airways disease

8

• Bronchiectasis

• Bronchopleural fistula

Clinical features: extrapulmonary disease

Non-pulmonary

• Empyema necessitans

• Laryngitis

• Enteritis(From swallowed sputum).

• Anorectal disease(From swallowed sputum).

• Amyloidosis

• Poncet's polyarthritis

TB Gastrointestinal disease

Upper gastrointestinal tract involvement is rare and is usually an

unexpected histological finding in an endoscopic or laparotomy specimen.

Ileocaecal disease accounts for approximately half of abdominal TB cases.

Fever, night sweats, anorexia and weight loss are usually prominent and a

right iliac fossa mass may be palpable.

Up to 30% of cases present with an acute abdomen.

Ultrasound or CT may reveal thickened bowel wall, abdominal

lymphadenopathy, mesenteric thickening or ascites.

TB Gastrointestinal disease .

Pericardial effusion and Constrictive pericarditis.

TB of the Central nervous system disease .

9

TB of Bone and Join Disease.

TB of Genitourinary disease

Contrast enhanced abdominal CT of a 21 year-old female patient demonstrates

multiple mesenteric lymphadenopathy forming a conglomerate mass (arrows) with 6

cm in major axis. Most enlarged nodes have central hypoenhancing areas due to

necrosis.

Diagnosis of Tuberculosis

Specimens required:

• Sputum* (induced with nebulised hypertonic saline if not expectorating) At

least 2 but preferably 3, including an early morning sample

• Bronchoscopy with washings or BAL

• Gastric washing* (mainly used for children) At least 2 but preferably 3,

including an early morning sample

Extrapulmonary

• Fluid examination (cerebrospinal, ascitic, pleural, pericardial, joint): yield

classically very low

• Tissue biopsy (from affected site); also bone marrow/liver may be

diagnostic in patients with disseminated disease

10

Diagnostic Tests

• Circumstantial (ESR, CRP, anaemia etc.)

• Tuberculin skin test (low sensitivity/specificity; useful only in primary or

deep-seated infection)

• Stain

• Ziehl-Neelsen

• Auramine fluorescence

• Nucleic acid amplification

• Culture

• Solid media (Löwenstein-Jensen, Middlebrook)

• Liquid media (e.g. BACTEC or MGIT) mycobacteria growth indicator

tube

• Response to empirical antituberculous drugs (usually seen after 5-10 days)

TB-Diagnostic tests :

The presence of an otherwise unexplained cough for more than 2-3 weeks,

particularly in an area where TB is highly prevalent, or typical chest X-ray

changes should prompt further investigation .

Direct microscopy of sputum is the most important first step.

The probability of detecting acid-fast bacilli is proportional to the bacillary

burden in the sputum (typically positive when 5000-10 000 organisms are

present).

By virtue of their substantial lipid-rich wall, tuberculous bacilli are difficult

to stain.

11

The most effective techniques are the Ziehl-Neelsen and rhodamine-

auramine stains.

The latter causes the tuberculous bacilli to fluoresce against a dark

background and is easier to use when numerous specimens need to be

examined;

However, it is more complex and expensive, limiting applicability in

resource-poor regions.

A positive smear is sufficient for the presumptive diagnosis of TB but

definitive diagnosis requires culture.

Smear-negative sputum should also be cultured, as only 10-100 viable

organisms are required for sputum to be culture-positive.

A diagnosis of smear-negative TB may be made in advance of culture if the

chest X-ray appearances are typical of TB and there is no response to a

broad-spectrum antibiotic.

MTB grows slowly and may take between 4 and 6 weeks to appear on solid

medium such as Löwenstein-Jensen or Middlebrook.

Faster growth (1-3 weeks) occurs in liquid media such as the radioactive

BACTEC system or the non-radiometric mycobacteria growth indicator tube

(MGIT).

The BACTEC method is commonly used in developed nations and detects

mycobacterial growth by measuring the liberation of

14

CO

2

, following

metabolism of

14

C-labelled substrate present in the medium.

12

New strategies for the rapid confirmation of TB at low cost are being developed;

These include the nucleic acid amplification test (NAT), designed to amplify

nucleic acid regions specific to MTB such as IS6110, and the MPB64 skin

patch test, in which immunogenic antigen detects active but not latent TB,

and has the potential to provide a simple, non-invasive test which does not

require a laboratory or highly skilled personnel.

Drug sensitivity testing is particularly important in those with a previous

history of TB, treatment failure or chronic disease, those who are resident

in or have visited an area of high prevalence of resistance, or those who are

HIV-positive.

The detection of rifampicin resistance, using molecular tools to test for the

presence of the rpo gene currently associated with around 95% of

rifampicin-resistant cases, is important as the drug forms the cornerstone

of 6-month chemotherapy..

• If a cluster of cases suggests a common source, confirmation may be sought

by fingerprinting of isolates with restriction-fragment length polymorphism

(RFLP) or DNA amplification.

• The diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB can be more challenging.

• There are generally fewer organisms (particularly in meningeal or pleural

fluid), so culture or histopathological examination of tissue is more

important.

• In the presence of HIV, however, examination of sputum may still be useful,

as subclinical pulmonary disease is common

Skin testing in TB:

Tests using purified protein derivative (PPD)

13

Heaf test

• Read at 3-7 days

• Multipuncture method

• Grade 1: 4-6 papules

• Grade 2: Confluent papules forming ring

• Grade 3: Central induration

• Grade 4: > 10 mm induration

Mantoux test

• Read at 2-4 days

• Using 10 tuberculin units

• Positive when induration 5-14 mm (equivalent to Heaf grade 2) and >

15 mm (Heaf grade 3-4)

Skin

False negatives

• Severe TB (25% of cases negative)

• Newborn and elderly

• HIV (if CD4 count < 200 cells/mL)

• Malnutrition

• Recent infection (e.g. measles) or immunisation

• Immunosuppressive drugs

• Malignancy

• Sarcoidosis

14

Skin testing in TB

Tuberculin skin testing may be associated with false-positive reactions in

those who have had a BCG vaccination and in areas where exposure to non-

tuberculous mycobacteria is high.

These limitations may be overcome by employing interferon-gamma

release assays (IGRAs).

These tests measure the release of IFN-γ from sensitised T cells in response

to antigens such as early secreted antigenic target (ESAT)-6 or culture

filtrate protein (CFP)-10 that are encoded by genes specific to the MTB and

are not shared with BCG or opportunistic mycobacteria.

The greater specificity of these tests, combined with the logistical

convenience of one blood test, as opposed to two visits for skin testing,

suggests that IGRAs will replace the tuberculin skin test in low-incidence,

high-income countries.

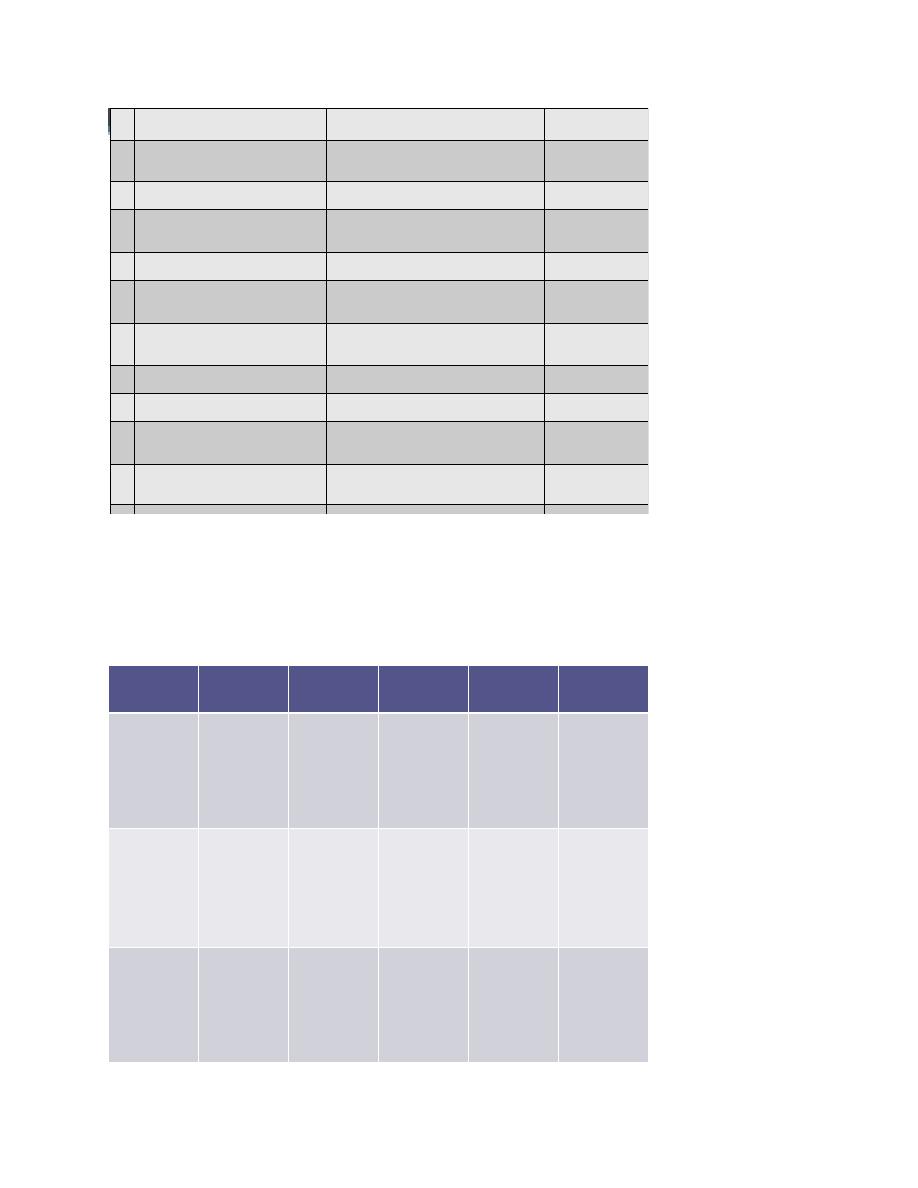

Managements and Chemotherapy

:

They are based on the principle of an initial intensive phase (which rapidly

reduces the bacterial population), followed by a continuation phase to

destroy any remaining bacteria.

Treatment should be commenced immediately in any patient who is smear-

positive, or who is smear-negative but with typical chest X-ray changes and

no response to standard antibiotics.

15

Continuation

phase

Initial phase*

Category of TB

4 months H

3

R

3

2 months H

3

R

3

Z

3

E

3

or 2 months

H

3

R

3

Z

3

S

3

(

i.e

3=week)

New cases of smear-positive

pulmonary TB

1

4 months HR

2 months HRZE or 2 months HRZS

Severe extra pulmonary TB

6 months HE

†

Severe smear-negative

pulmonary TB

Severe concomitant HIV disease

5 months

H

3

R

3

E

3

2 months H

3

R

3

Z

3

E

3

or 1 month

H

3

R

3

Z

3

E

Previously treated smear-

positive pulmonary TB

2

5 months HRE

2 months HRZES or 1 month

HRZE

Relapse

Treatment failure

Treatment after default

4 months H

3

R

3

2 months H

3

R

3

Z

3

E

3

New cases of smear-negative

pulmonary TB

3

4 months HR

2 months HRZE

Less severe extrapulmonary

TB

6 months HE

†

H= isoniazid;; E =ethambutol; R = rifampicin; Z = pyrazinamide

S = streptomycin

Ethambutol

Streptomycin

Pyrazinamide

Rifampicin

Isoniazid

Cell wall

synthesis

Protein

synthesis

Unknown

DNA

transcription

Cell wall

synthesis

Mode of

action

Retrobulbar

neuritis

3

Arthralgia

8th nerve

damage

Rash

Hepatitis

Gastrointesti

nal

disturbance

Hyperuricae

mia

Febrile

reactions

Hepatitis

Rash

Gastrointesti

nal

disturbance

Peripheral

neuropathy

1

Hepatitis

2

Rash

Major

adverse

reactions

Peripheral

neuropathy

Rash

Nephrotoxici

ty

Agranulocyt

osis

Rash

Photosensiti

sation

Gout

Interstitial

nephritis

Thrombocyt

openia

Haemolytic

anaemia

Lupoid

reactions

Seizures

Psychoses

Less

common

adverse

reactions

16

Quadruple therapy has become standard in the UK, although Ethambutol

may be omitted under certain circumstances.

Fixed-dose tablets combining two or three drugs are generally favoured: for

example, Rifater (rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide) daily for 2

months, followed by 4 months of Rifinah (rifampicin and isoniazid).

Streptomycin is rarely used in the UK, but is an important component of

short-course treatment regimens in developing nations.

Six months of therapy is appropriate for all patients with new-onset,

uncomplicated pulmonary disease.

However, 9-12 months of therapy should be considered if the patient is

HIV-positive, or if drug intolerance occurs and a second-line agent is

substituted.

Meningitis should be treated for a minimum of 12 months.

Pyridoxine should be prescribed in pregnant women and malnourished

patients to reduce the risk of peripheral neuropathy with isoniazid.

Where drug resistance is not anticipated, patients can be assumed to be

non-infectious after 2 weeks of appropriate therapy.

Most patients can be treated at home. .

Admission to a hospital unit with appropriate isolation facilities should be

considered where there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, intolerance of

medication, questionable compliance, adverse social conditions or a

significant risk of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB:

17

Culture-positive after 2 months on treatment, or contact with known MDR-

TB).

In choosing a suitable drug regimen, underlying comorbidity (renal and

hepatic dysfunction, eye disease, peripheral neuropathy and HIV status), as

well as the potential for drug interactions, must be considered.

• Baseline liver function and regular monitoring are important for patients

treated with standard therapy including rifampicin, isoniazid and

pyrazinamide, as all of these agents are potentially hepatotoxic.

• Mild asymptomatic increases in transaminases are common but serious

liver damage is rare.

• Women taking the oral contraceptive pill must be warned that its efficacy

will be reduced and alternative contraception may be necessary.

• Ethambutol should be used with caution in patients with renal failure, with

appropriate dose reduction and monitoring of drug levels.

• Adverse drug reactions occur in about 10% of patients, but are significantly

more common in the presence of HIV co-infection .

Corticosteroids reduce inflammation and limit tissue damage, and are

currently recommended when treating pericardial or meningeal disease,

and in children with endobronchial disease.

They may confer benefit in TB of the ureter, pleural effusions and extensive

pulmonary disease, and can suppress hypersensitivity drug reactions.

Surgery is still occasionally required (e.g. for massive haemoptysis,

loculated empyema, constrictive pericarditis, lymph node suppuration,

spinal disease with cord compression), but usually only after a full course of

antituberculosis treatment

18

Control and prevention of TB:

The effectiveness of therapy for pulmonary TB may be judged by a further

sputum smear at 2 months and at 5 months.

A positive sputum smear at 5 months defines treatment failure.

Extrapulmonary TB must be assessed clinically or radiographically as

appropriate.

The WHO is committed to reducing the incidence of TB by 2015.

Important components of this goal include supporting the development of

laboratory and health-care services to improve detection and treatment of

active and latent TB.

Detection of latent TB

• It has the potential to identify the probable index case, other cases infected

by the same index patient (with or without evidence of disease), and close

contacts who should receive BCG vaccination (see below) or chemotherapy.

• Approximately 10-20% of close contacts of patients with smear-positive

pulmonary TB and 2-5% of those with smear-negative, culture-positive

disease have evidence of TB infection.

• Cases are commonly identified using the tuberculin skin test (Box 19.63 and

Fig. 19.39).

• An otherwise asymptomatic contact with a positive tuberculin skin test but

a normal chest X-ray may be treated with chemoprophylaxis to prevent

infection progressing to clinical disease

• .Chemoprophylaxis is also recommended for children aged less than 16

years identified during contact tracing to have a strongly positive tuberculin

test, children aged less than 2 years in close contact with smear-positive

19

pulmonary disease, those in whom recent tuberculin conversion has been

confirmed, and babies of mothers with pulmonary TB.

• It should also be considered for HIV-infected close contacts of a patient

with smear-positive disease.

• Rifampicin plus isoniazid for 3 months or isoniazid for 6 months is effective

Directly observed therapy (DOT) :

• Poor adherence to therapy is a major factor in prolonged infectious illness,

risk of relapse and the emergence of drug resistance.

• DOT involves the supervised administration of therapy thrice weekly and

improves adherence.

• It has become an important control strategy in resource-poor nations.

• In the UK, it is currently only recommended for patients thought unlikely to

be adherent to therapy:

• Those who are homeless, alcohol or drug users, drifters, those with serious

mental illness and those with a history of non-compliance

20

4th stage

باطنية

Lec-5

د.ظاهر

8/11/2015

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis means abnormal dilatation of the bronchi.

Chronic suppurative airway infection with sputum production, progressive

scarring and lung damage are present, whatever the cause.

Aetiology and pathogenesis Bronchiectasis

Congenital defect affecting airway ion transport or ciliary function, such as

cystic fibrosis .

Acquired secondary to damage to the airways by a destructive infection,

inhaled toxin or foreign body. The result is chronic inflammation

,tuberculosis is the most common world-wide.

Localised bronchiectasis may occur due to the accumulation of pus beyond

an obstructing bronchial lesion, such as enlarged tuberculous hilar lymph

nodes, a bronchial tumour or an inhaled foreign body (e.g. an aspirated

peanut).

Pathology

The bronchiectatic cavities may be lined by granulation tissue, squamous

epithelium or normal ciliated epithelium.

Chronic inflammatory and fibrotic changes are usually found in the

surrounding lung tissue, resulting in progressive destruction of the normal

lung architecture in advanced case

21

Clinical features and symptoms of bronchiectasis(table)

Physical signs in the chest may be unilateral or bilateral. If the

bronchiectatic airways do not contain secretions and there is no associated

lobar collapse, there are no abnormal physical signs.

When there are large amounts of sputum in the bronchiectatic spaces,

numerous coarse crackles may be heard over the affected areas.

Acute haemoptysis is an important complication of bronchiectasis;

management is covered on page

Investigations Bacteriological and mycological examination of sputum

In addition to common respiratory pathogens, sputum culture may reveal

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, fungi such as Aspergillus and various

mycobacteria..

This time should not exceed 20 minutes but is greatly prolonged in patients

with ciliary dysfunction.

Ciliary beat frequency may also be assessed using biopsies taken from the

nose. Structural abnormalities of cilia can be detected by electron

microscopy.

Management

In airflow obstruction, inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids should

be used to enhance airway patency.

Physiotherapy Patients should be instructed on how to perform regular

daily physiotherapy to assist the drainage of excess bronchial secretions.

Patients should adopt a position in which the lobe to be drained is

uppermost.

22

Deep breathing followed by forced expiratory (the 'active cycle of

breathing' technique) is of help in moving secretions in the dilated bronchi

towards the trachea, from which they can be cleared by vigorous coughing.

'Percussion' of the chest wall with cupped hands may help to dislodge

sputum, but does not suit all patients. .

The optimum duration and frequency of physiotherapy depend on the

amount of sputum, but 5-10 minutes once or twice daily is a minimum for

most patients.

Antibiotic therapy in general, require larger doses and longer courses .

When secondary infection occurs with staphylococci and Gram-negative

bacilli, in particular Pseudomonas species, antibiotic therapy becomes more

challenging and should be guided by the microbiological sensitivities.

For Pseudomonas, oral ciprofloxacin (250-750 mg 12-hourly) or ceftazidime

by intravenous injection or infusion (1-2 g 8-hourly) may be required.

Haemoptysis in bronchiectasis often responds to treating the underlying

infection, although in severe cases percutaneous embolisation of the

bronchial circulation by an interventional radiologist may be necessary.

Surgical treatment Excision of bronchiectatic areas is only indicated in a

small proportion of cases.

Cystic fibrosis:

The most common fatal genetic disease in Caucasians, with autosomal recessive

inheritance.

CF is the result of mutations affecting a gene on the long arm of chromosome 7

which codes for a chloride channel known as cystic fibrosis transmembrane

conductance regulator (CFTR), that influences salt and water movement across

epithelial cell membranes.

23

This lead to increased sodium and chloride content in sweat and increased

resorption of sodium and water from respiratory epithelium.

Relative dehydration of the airway epithelium is thought to predispose to chronic

bacterial infection and ciliary dysfunction, leading to bronchiectasis.

The gene defect also causes disorders in the gut epithelium, pancreas, liver and

reproductive tract .

Clinical features

The lungs are most commonly infected with Staphylococcus aureus; however,

many patients become colonised with Pseudomonas aeruginosa by the time they

reach adulthood.

The upper lobes but subsequently throughout both lungs, cause progressive lung

damage resulting ultimately in death from respiratory failure.

Most men with CF are infertile due to failure of development of the vas deferens,

but microsurgical sperm aspiration and in vitro fertilisation are now possible.

Complications of cystic fibrosis

Respiratory :

Infective exacerbations of bronchiectasis,Spontaneous

pneumothorax,Haemoptysis,Nasal polyps,Respiratory failure,Cor

pulmonale,Lobar collapse due to secretions .

Gastrointestinal: Malabsorption and steatorrhoea,Distal intestinal obstruction

syndrome ,Biliary cirrhosis and portal hypertension,Gallstones

Others :Diabetes (25% of adults),Delayed puberty,Male infertility,Stress

incontinence due to repeated forced cough ,Psychosocial

problems,Osteoporosis,Arthropathy,Cutaneous vasculitis.

24

Management

Treatment of CF lung disease :

The management of CF lung disease is that of severe bronchiectasis. All patients

with CF who produce sputum should perform regular chest physiotherapy, and

should do so more frequently during exacerbations. While infections with Staph.

aureus can often be managed with oral antibiotics, intravenous treatment (often

self-administered at home through a subcutaneous vascular port) is usually

needed for Pseudomonas species. Regular nebulised antibiotic therapy

(colomycin or tobramycin) is used between exacerbations in an attempt to

suppress chronic Pseudomonas infection.

Treatments that may reduce chest exacerbations and/or improve lung function in

CF

1) Nebulised recombinant human DNase 2.5 mg daily used in patient Age ≥ 5, FVC

> 40% predicted

2) Nebulised tobramycin 300 mg 12-hourly, given in alternate months used in

Patients colonised with pseudomonas aeruginosa

3)Regular oral azithromycin 500 mg three times/week used in Patients colonised

with Pseudomonas aeruginosa .

Bronchi of many CF patients eventually become colonised with pathogens which

are resistant to most antibiotics. Resistant strains of P. aeruginosa,

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Burkholderia cepacia are the main culprits,

and may require prolonged treatment with unusual combinations of antibiotics.

Aspergillus and 'atypical mycobacteria' are also frequently found in the sputum of

CF patients, but in most cases these behave as benign 'colonisers' of the

bronchiectatic airways and do not require specific therapy.

25

Some patients have coexistent asthma, which is treated with inhaled

bronchodilators and corticosteroids; allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis also

occurs occasionally in CF.

For advanced CF lung disease, home oxygen and NIV may be necessary to treat

respiratory failure.

Ultimately, lung transplantation can produce dramatic improvements but is

limited by donor organ availability.

Treatment of non-respiratory manifestations of CF

Malabsorption is treated with oral pancreatic enzyme supplements and vitamins.

The increased calorie requirements of CF patients are met by supplemental

feeding, including nasogastric or gastrostomy tube feeding if required.

Diabetes eventually appears in over 25% of patients and often requires insulin

therapy. Osteoporosis secondary to malabsorption and chronic ill health should

be sought and treated.

Somatic gene therapy :

The discovery of the CF gene and the fact that the lethal defect is located in the

respiratory epithelium (which is accessible by inhaled therapy) presents an

exciting opportunity for gene therapy. Manufactured normal CF gene can be

'packaged' within a viral or liposome vector and delivered to the respiratory

epithelium to correct the genetic defect.

26

4th stage

باطنية

Lec-6

د.ظاهر

8/11/2015

TUMOURS OF THE BRONCHUS AND LUNG

The burden of lung cancer

• Cigarette smoking is by far the most important cause of lung cancer., for at

least 90 being proportional to the amount smoked and to the tar content of

cigarettes.

• The death rate from the disease in heavy smokers is 40 times that in non-

smokers. Risk falls slowly after smoking cessation, but remains above that

in non-smokers for many years

• Exposure to naturally occurring radon is another risk.

• The incidence of lung cancer is slightly higher in urban than in rural

dwellers.which may reflect differences in atmospheric .

Bronchial carcinoma:

• Bronchial carcinomas arise from the bronchial epithelium or mucous

glands.With Lymphatic spread &or Blood-borne metastases .

• The common cell types are:

• Squamous30-35%,

• Adenocarcinoma40-30%,

• Small-cell20%, spread very fast

• and Large-cell 15%.

• Tumour occurs in a large bronchus, symptoms arise early, but tumours

originating in a peripheral bronchus can grow very large without producing

symptoms, resulting in delayed diagnosis.

• Peripheral squamous tumours may undergo central necrosis and cavitation,

and may resemble a lung abscess on X-ray .

27

Clinical Presentation of Bronchial carcinoma

1. Cough.

2. Haemoptysis. Occasionally, central tumours invade large vessels, causing

sudden massive haemoptysis which may be fatal.

3. Bronchial obstruction.Complete obstruction causes collapse of a lobe or

lung, Partial bronchial obstruction may cause a monophonic, unilateral

wheeze that fails to clear with cough.

4. Pneumonia that recurs at the same site.

5. Stridor (a harsh inspiratory noise) occurs when the lower trachea,.

6. Breathlessness. This may be caused by collapse or pneumonia, or by

tumour causing a large pleural effusion or compressing a phrenic nerve

causing diaphragmatic paralysis.

7. Pain and nerve entrapment. Pleural pain usually indicates malignant pleural

invasion.

8. Carcinoma in the lung apex may cause Horner's syndrome (ipsilateral

partial ptosis, enophthalmos, miosis and hypohidrosis of the face due to

involvement of the sympathetic chain at or above the stellate ganglion.

9. Pancoast's syndrome, malignant destruction of the T1 and C8 roots.

Mediastinal spread. Involvement of the oesophagus may cause dysphagia.

10. If the pericardium, arrhythmia or pericardial effusion ..

11. Superior vena cava obstruction,left recurrent laryngeal nerve

12. Supraclavicular lymph nodes ,Digital clubbing& Hypertrophic pulmonary

osteoarthropathy (HPOA),

13. Non-metastatic extrapulmonary effects .Syndrome of inappropriate

antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) and ectopic adrenocorticotrophic

hormone secretion are usually associated with small-cell lung cancer

14. Hypercalcaemia is usually caused by squamous cell carcinoma.

15. Associated neurological syndromes may occur with any type of bronchial

carcinoma

28

Non-metastatic extrapulmonary manifestations of bronchial carcinoma

Endocrine

• Inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion causing hyponatraemia

• Ectopic adrenocorticotrophic hormone secretion

• Hypercalcaemia due to secretion of parathyroid hormone-related peptides

• Carcinoid syndrome

• Gynaecomastia

• Non-metastatic extrapulmonary manifestations of bronchial carcinoma

Neurological

• Polyneuropathy

• Myelopathy

• Cerebellar degeneration

• Myasthenia (Lambert-Eaton syndrome).

Other

• Digital clubbing

• Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy

• Nephrotic syndrome

• Polymyositis and dermatomyositis

• Eosinophilia

29

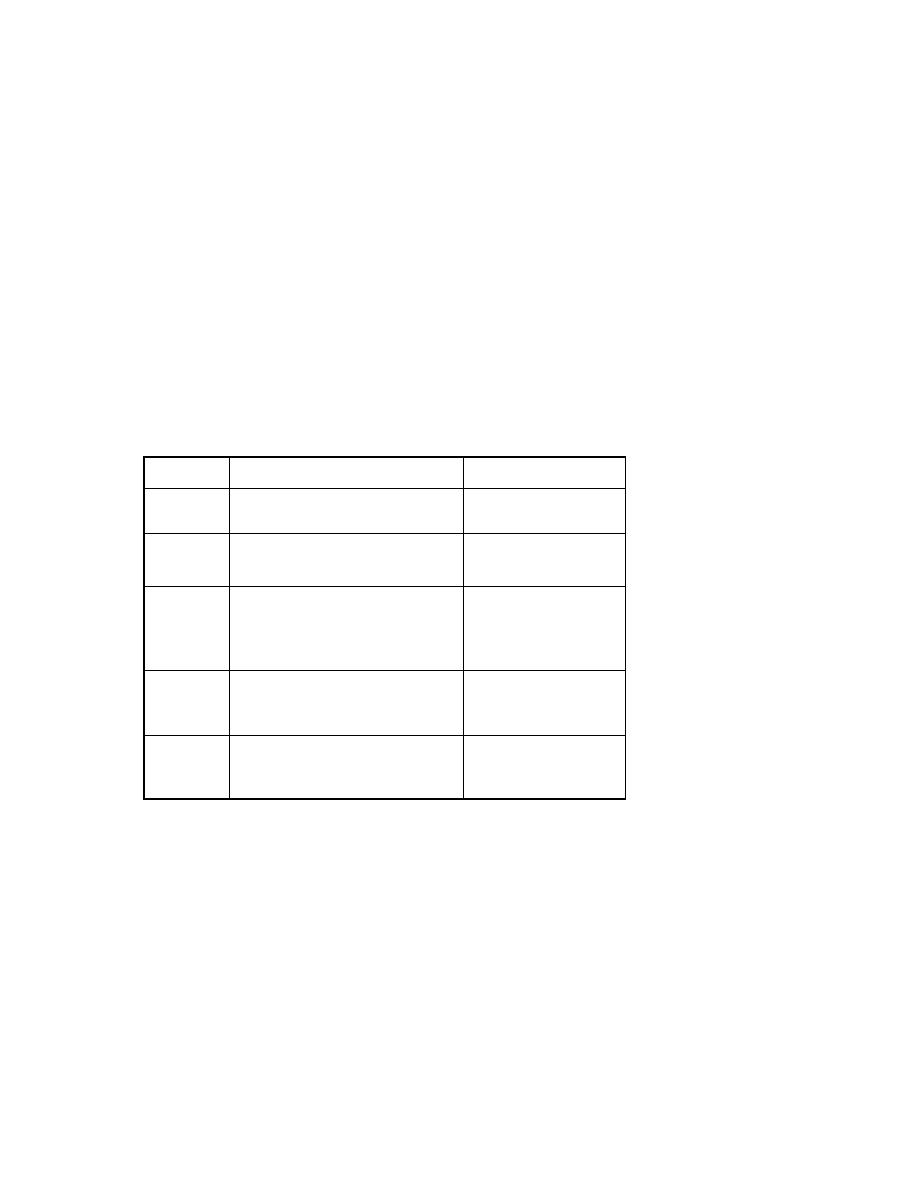

Investigations for Bronchial carcinoma

• Plain X-rays

• CT is usually performed for :

localization,operability, metastatic spread

and for accessible or not by bronchoscopy .

Bronchoscopy ;three-quarters of primary lung tumours can be visualised and

sampled directly by biopsy and brushing using a flexible bronchoscope.

Percutaneous needle biopsy under CT or ultrasound guidance; more reliable way

to obtain a histological diagnosis for tumours which are too peripheral

Large cavitated bronchial carcinoma in left lower

lobe

30

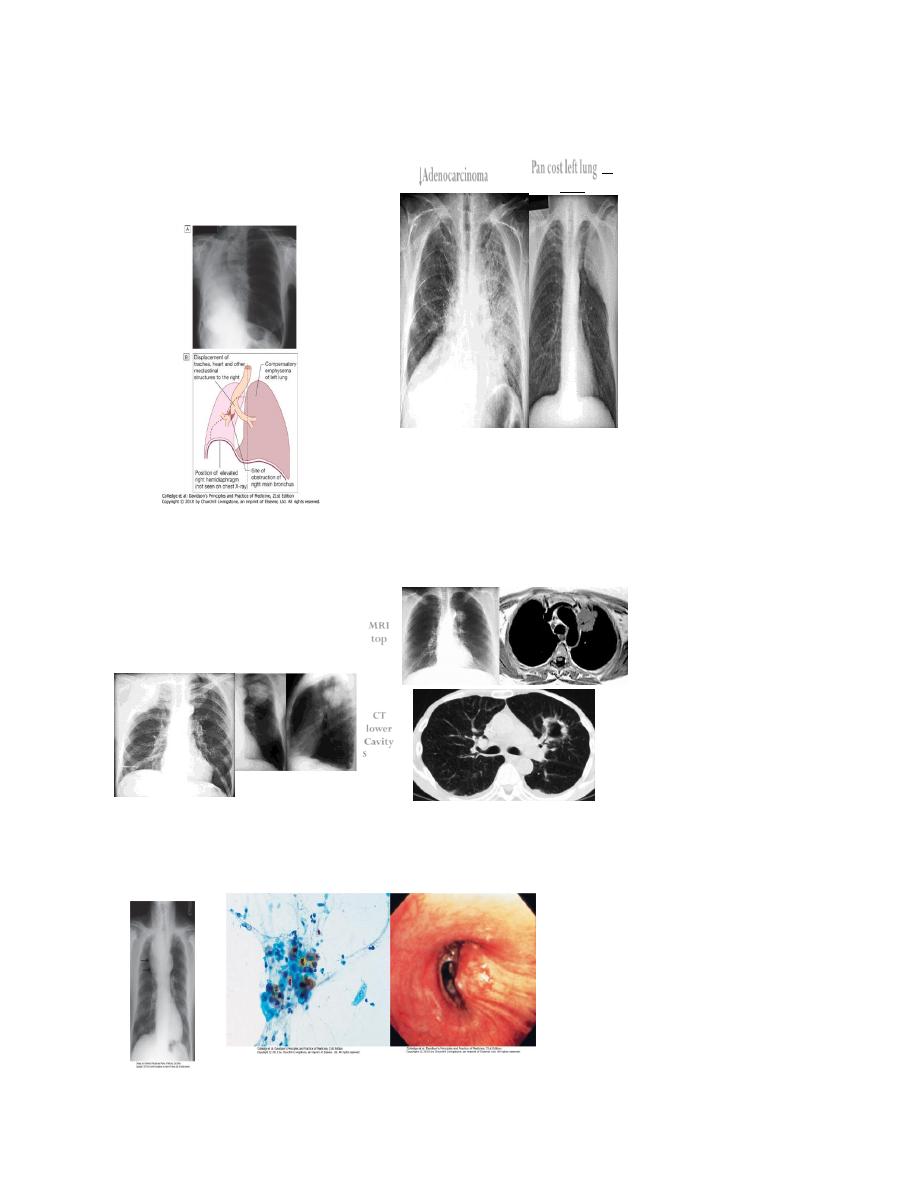

↓Adenocarcinoma

Pan cost left lung↓

with

Rib eroson

↓Pancost Right lung

Pancostleft lung

↓

MRI

top

CT

lower

Cavity

Squ.carc

31

Management

• Surgical resection carries the best hope of long-term survival; however,

some patients treated with radical radiotherapy and chemotherapy also

achieve prolonged remission or cure.

• Unfortunately, in over 75% of cases, treatment with curative intent is not

possible, or is inappropriate due to extensive spread or comorbidity. Such

patients can only be offered palliative therapy and best supportive care.

• Radiotherapy, and in some cases chemotherapy, can relieve distressing

symptoms

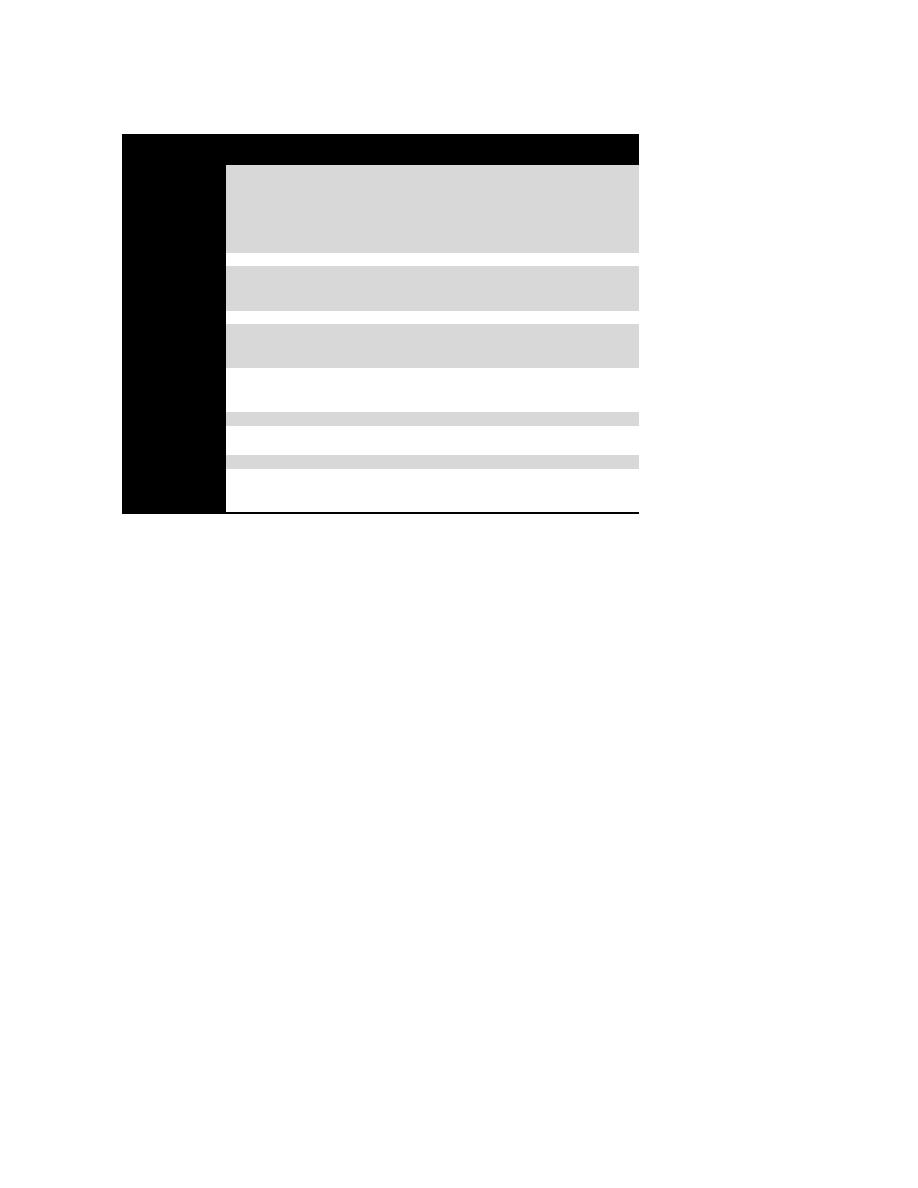

Treatment and Staging NSCLC

Stage

Description

Treatment Options

Stage I a/ b

Tumor of any size is found only in

the lung

Surgery

Stage II a/ b Tumor has spread to lymph nodes

associated with the lung

Surgery

Stage III a

Tumor has spread to the lymph

nodes in the tracheal area,

including chest wall and

diaphragm

Chemotherapy

followed by radiation

or surgery

Stage III b

Tumor has spread to the lymph

nodes on the opposite lung or in

the neck

Combination of

chemotherapy and

radiation

Stage IV

Tumor has spread beyond the chest Chemotherapy and/ or

palliative

(maintenance) care

32

Surgical treatment :

• Accurate pre-operative staging, coupled with improvements in surgical and

post-operative care, now offers 5-year survival rates of over 75% in stage I

disease (N0, tumour confined within visceral pleura) and 55% in stage II

disease, which includes resection in patients with ipsilateral peribronchial

or hilar node involvement.

Contraindications to surgical resection in bronchial carcinoma

• Distant metastasis (M1)

• Invasion of central mediastinal structures including heart, great vessels,

trachea and oesophagus (T4)

• Malignant pleural effusion (T4)

• Contralateral mediastinal nodes (N3)

• FEV

1

< 0.8 L

• Severe or unstable cardiac or other medical condition

Radiotherapy :

• While much less effective than surgery, radical radiotherapy can offer long-

term survival in selected patients with localised disease in whom

comorbidity precludes surgery.

• Continuous hyper-fractionated accelerated radiotherapy (CHART), in which

a similar total dose is given in smaller but more frequent fractions, may

offer better survival prospects than conventional schedules.

• The greatest value of radiotherapy, however, is in the palliation of

distressing complications such as superior vena cava obstruction, recurrent

haemoptysis, and pain caused by chest wall invasion or by skeletal

metastatic deposits

33

• . Obstruction of the trachea and main bronchi can also be relieved

temporarily.

• can be used in conjunction with chemotherapy in the treatment of small-

cell carcinoma, and is particularly efficient at preventing the development

of brain metastases in patients who have had a complete response to

chemotherapy

Chemotherapy

• The treatment of small-cell carcinoma with combinations of cytotoxic

drugs, sometimes in combination with radiotherapy, can increase the

median survival from 3 months to well over a year.

• Combination chemotherapy leads to better outcomes than single-agent

treatment.

• In particular, oral etoposide leads to more toxicity and worse survival than

standard combination chemotherapy.

• Regular cycles of therapy, including combinations of i.v. cyclophosphamide,

doxorubicin and vincristine or i.v. cisplatin and etoposide, are commonly

used.

• Nausea and vomiting are common side-effects and are best treated with 5-

HT

3

receptor antagonists

• The use of combinations of chemotherapeutic drugs requires considerable

skill and should be overseen by teams of expert clinicians and nurses.

• In general, chemotherapy is less effective in non-small-cell bronchial

cancers.

• However, studies in such patients using platinum-based chemotherapy

regimens have shown a 30% response rate associated with a small increase

in survival.

34

Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy:

• In non-small-cell carcinoma, there is some evidence that chemotherapy

given before surgery may increase survival and can effectively 'down-stage'

disease with limited nodal spread.

• Post-operative chemotherapy is now proven to improve survival rates

when operative samples show nodal involvement by tumour.

Laser therapy and stenting :

• Palliation of symptoms caused by major airway obstruction can be achieved

in selected patients using bronchoscopic laser treatment to clear tumour

tissue and allow re-aeration of collapsed lung.

• The best results are achieved in tumours of the main bronchi.

Endobronchial stents can be used to maintain airway patency in the face of

extrinsic compression by malignant nodes

General aspects of management :

• The best outcomes are obtained when lung cancer is managed in specialist

centres by multidisciplinary teams including oncologists, thoracic surgeons,

respiratory physicians and specialist nurses; effective communication, pain

relief and attention to diet are important.

• Lung tumours can cause clinically significant depression and anxiety, and

these may need specific therapy. The management of non-metastatic

endocrine manifestations is described in

. When a malignant

pleural effusion is present, an attempt should be made to drain the pleural

cavity using an intercostal drain; provided the lung fully re-expands,

pleurodesis with a sclerosing agent such as talc should be performed

35

Prognosis:

• The overall prognosis in bronchial carcinoma is very poor, with around 70%

of patients dying within a year of diagnosis and only 6-8% of patients

surviving 5 years after diagnosis.

• The best prognosis is with well-differentiated squamous cell tumours that

have not metastasised and are amenable to surgical resection.

Secondary tumours of the lung:

• Blood-borne metastatic deposits in the lungs may be derived from many

primary tumours, in particular the breast, kidney, uterus, ovary, testes and

thyroid.

• The secondary deposits are usually multiple and bilateral. Often there are

no respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis is made on radiological

examination.

• Breathlessness may occur if a considerable amount of lung tissue has been

replaced by metastatic tumour. Endobronchial deposits are uncommon but

can cause haemoptysis and lobar collapse

36

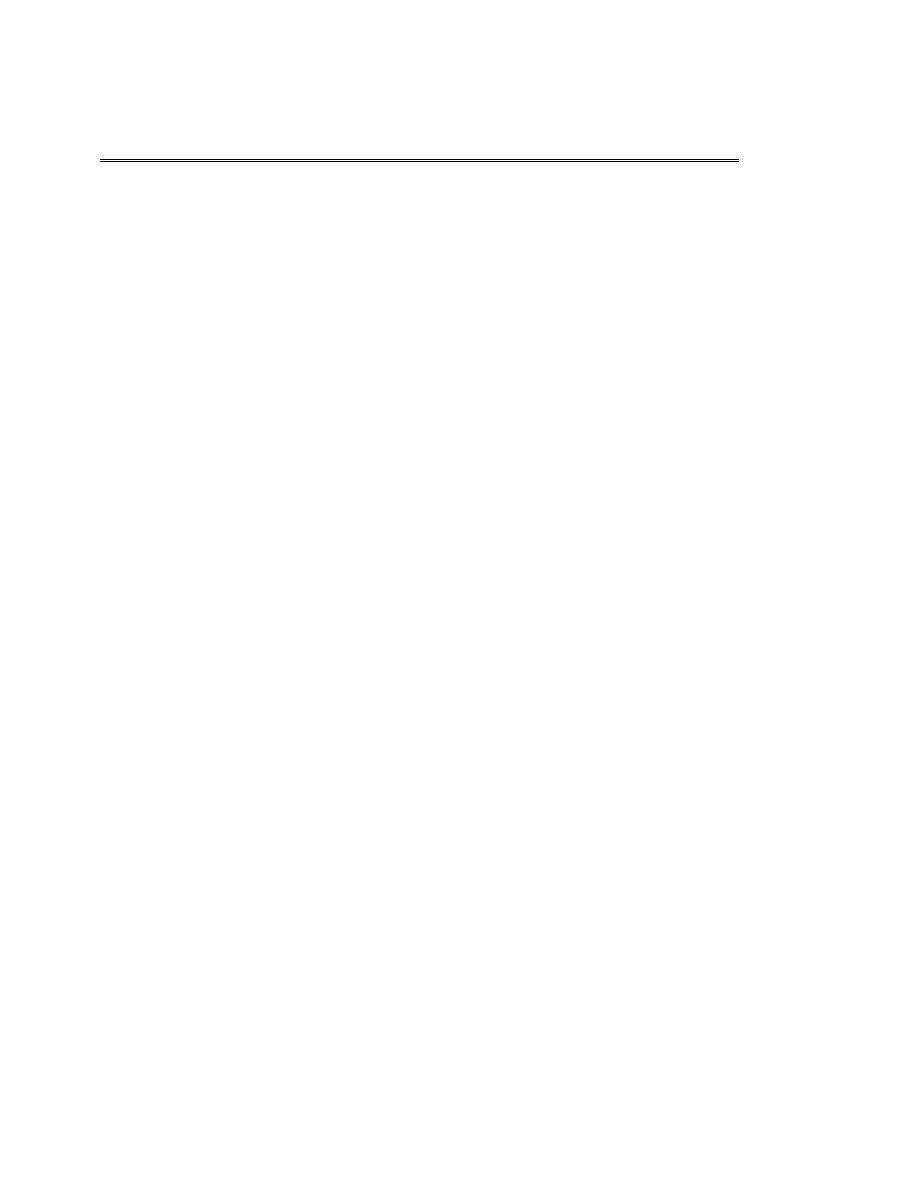

Rare types of lung tumour

Tumour

Status

Histology

Typical presentation

Prognosis

Adenosquamous carcinoma

Malignant

Tumours with areas of

unequivocal squamous and

adeno-differentiation

Peripheral or central lung mass

Stage-dependent

Carcinoid tumour

Low-grade malignant

Neuroendocrine differentiation

Bronchial obstruction, cough

95% 5-year survival with

resection

Bronchial gland adenoma

Benign

Salivary gland differentiation

Tracheobronchial

irritation/obstruction

Local resection curative

Bronchial gland carcinoma

Low-grade malignant

Salivary gland differentiation

Tracheobronchial

irritation/obstruction

Local recurrence occurs

Hamartoma

Benign

Mesenchymal cells, cartilage

Peripheral lung nodule

Local resection curative

Bronchoalveolar carcinoma

Malignant

Tumour cells line alveolar

spaces

Alveolar shadowing, productive

cough

Variable, worse if multifocal