Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

SECRETION AND ABSORPTION IN

THE SMALL INTESTINE

The small intestine is the portal for absorption of virtually all nutrients into blood.

Accomplishing this transport requires breaking down large supramolecular aggregates into

small molecules that can be transported across the epithelium.

By the time ingesta reaches the small intestine, foodstuffs have been mechanically broken

down and reduced to a liquid by mastication and grinding in the stomach. Once within the

small intestine, these macromolecular aggregates are exposed to pancreatic enzymes and

bile, which enables digestion to molecules capable or almost capable of being absorbed.

The final stages of digestion occur on the surface of the small intestinal epithelium.

The net effect of passage through the small intestine is absorption of most of the water

and electrolytes (sodium, chloride, potassium) and essentially all dietary organic molecules

(including glucose, amino acids and fatty acids). Through these activities, the small

intestine not only provides nutrients to the body, but plays a critical role in water and

acid-base balance.

Secretion in the Small Intestine

Large quantities of water are secreted into the lumen of the small intestine during the

digestive process. Almost all of this water is also reabsorbed in the small intestine.

Regardless of whether it is being secreted or absorbed, water flows across the mucosa in

response to osmotic gradients. In the case of secretion, two distinct processes establish

an osmotic gradient that pulls water into the lumen of the intestine:

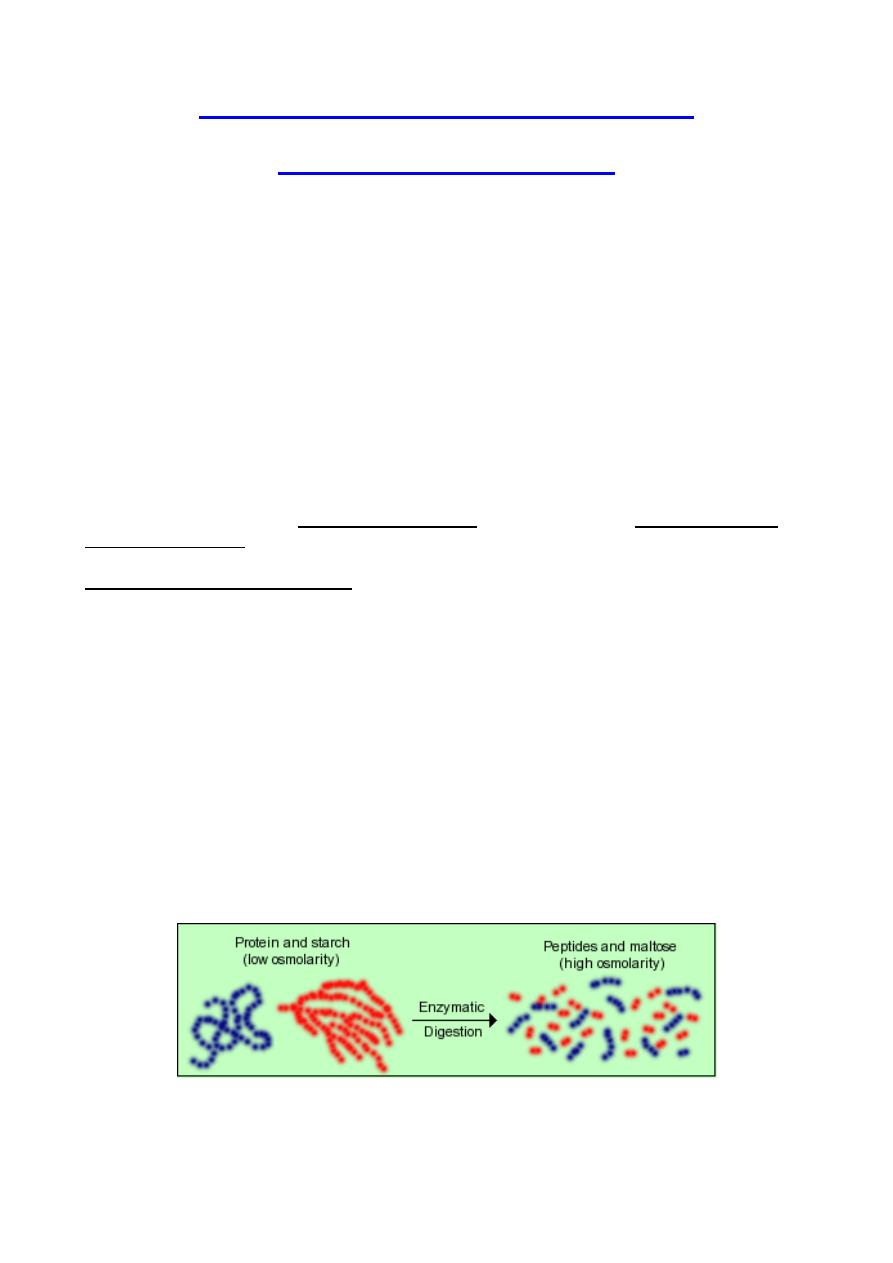

1. Increases in luminal osmotic pressure resulting from influx and digestion of

foodstuffs: The chyme that floods into the intestine from the stomach

typically is not hyperosmotic, but as its macromolecular components are

digested, osmolarlity of that solution increases dramatically.

Starch, for example, is a huge molecule that contributes only a small amount to osmotic

pressure, but as it is digested, thousands of molecules of maltose are generated, each of

which is as osmotically active as the original starch molecule.

Thus, as digestion proceeds lumenal osmolarity increases dramatically and water is pulled

into the lumen. Then, as the osmotically active molecules (maltose, glucose, amino acids)

are absorbed, osmolarity of the intestinal contents decreases and water can be absorbed.

Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

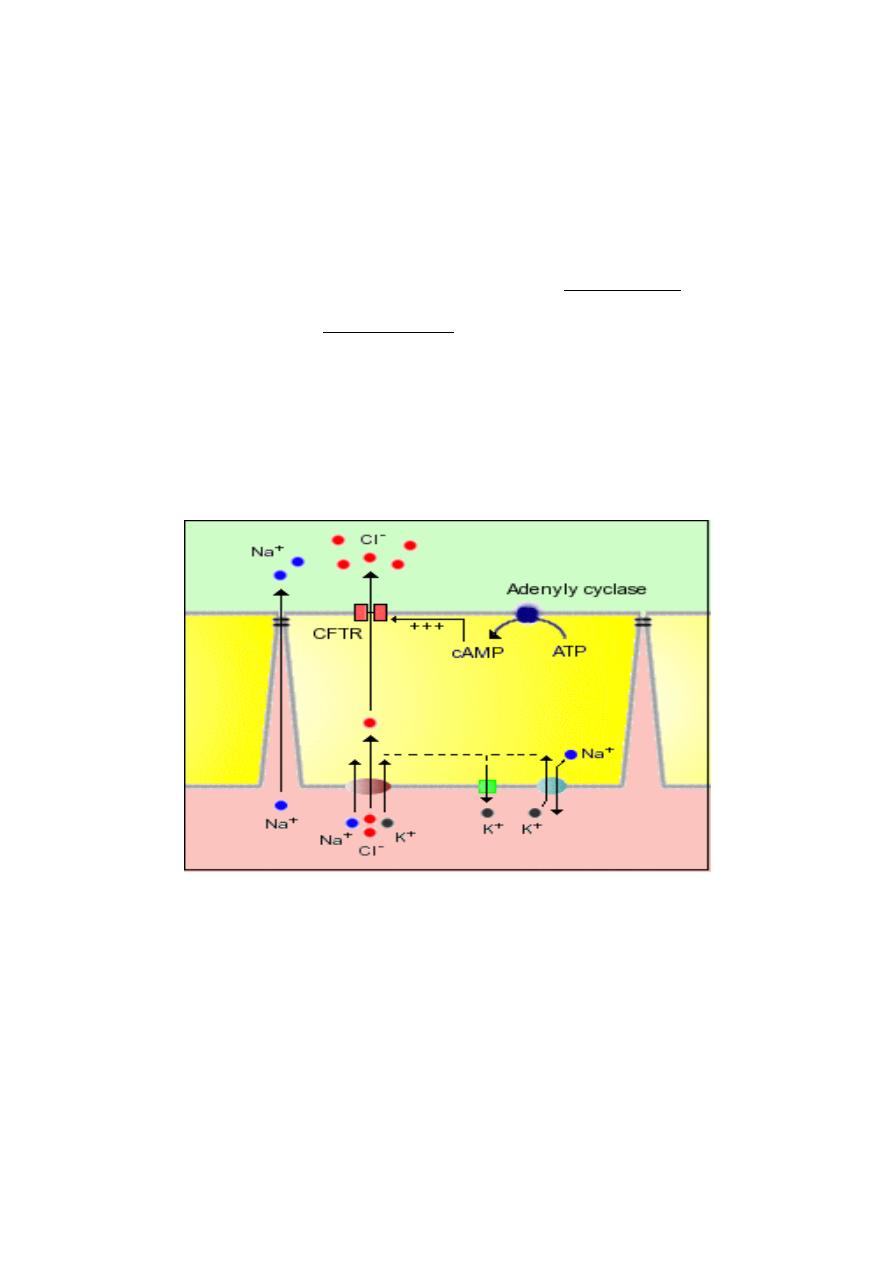

2. Crypt cells actively secrete electrolytes, leading to water secretion: The apical

or lumenal membrane of crypt epithelial cells contain an ion channel of

immense medical significance - a cyclic AMP-dependent chloride channel

known also as the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator or

CFTR. Mutations in the gene for this ion channel result in the disease cystic

fibrosis. This channel is responsible for secretion of water by the following

steps:

1. Chloride ions enter the crypt epithelial cell by cotransport with sodium and

potassium; sodium is pumped back out via sodium pumps, and

potassium is exported via a number of channels.

2. Activation of adenylyl cyclase by a number of so-called secretagogues

leads to generation of cyclic AMP.

3. Elevated intracellular concentrations of cAMP in crypt cells activate the

CFTR, resulting in secretion of chloride ions into the lumen.

4. Accumulation of negatively-charged chloride anions in the crypt creates

an electric potential that attracts sodium, pulling it into the lumen,

apparently across tight junctions - the net result is secretion of NaCl.

5. Secretion of NaCl into the crypt creates an osmotic gradient across the

tight junction and water is drawn into the lumen.

CLINICAL CORRELATION

Cystic fibrosis

Abnormal activation of the cAMP-dependent chloride channel (CFTR) in crypt cells has

resulted in the deaths of millions upon millions of people. Several types of bacteria

produce toxins that strongly, often permanently, activate the adenylate cyclase in crypt

enterocytes. This leads to elevated levels of cAMP, causing the chloride channels to

essentially become stuck in the "open" position". The result is massive secretion of water

that is manifest as severe diarrhea. Cholera toxin, produced by cholera bacteria, is the

best known example of this phenomenon, but several other bacteria produce toxins that

act similarly.

Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

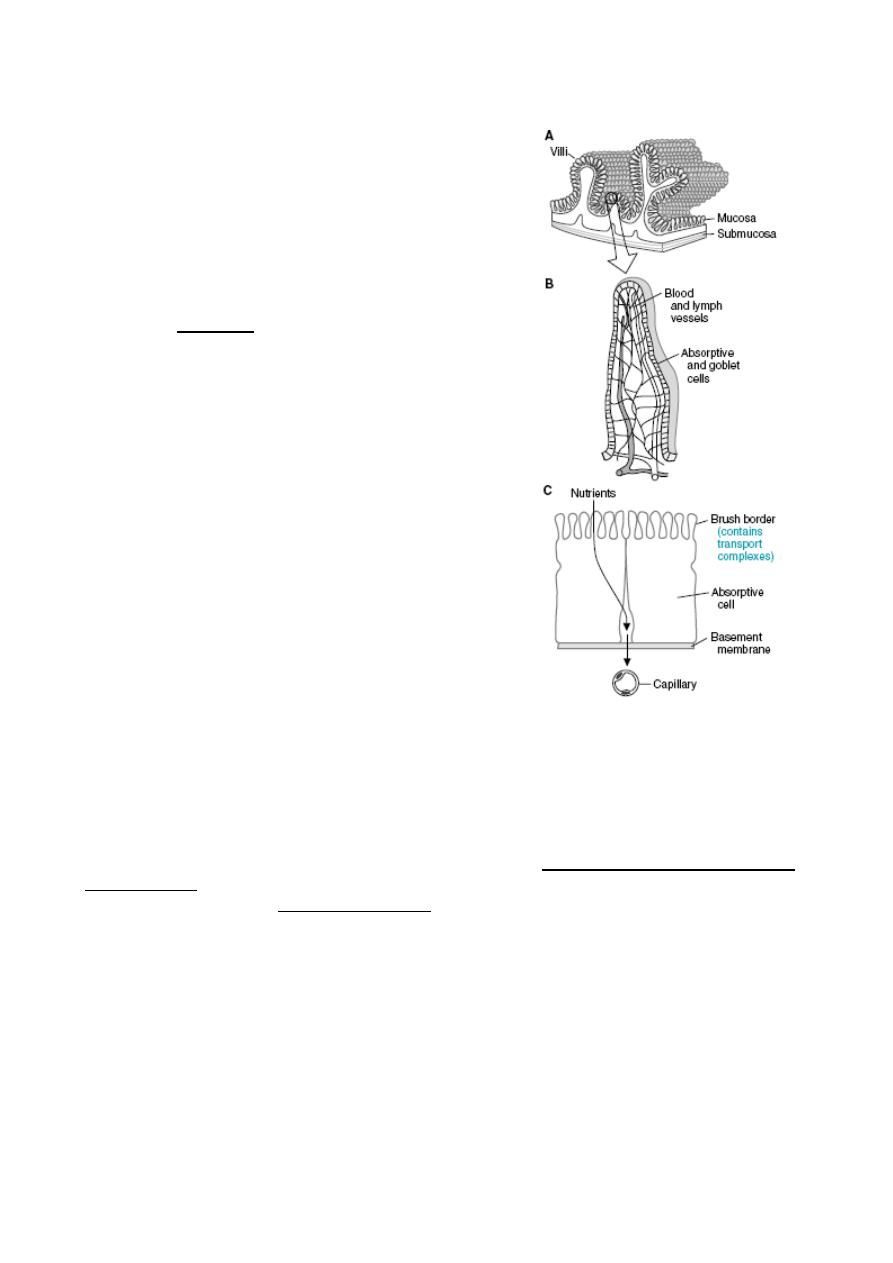

Absorption in the Small Intestine: General Mechanisms

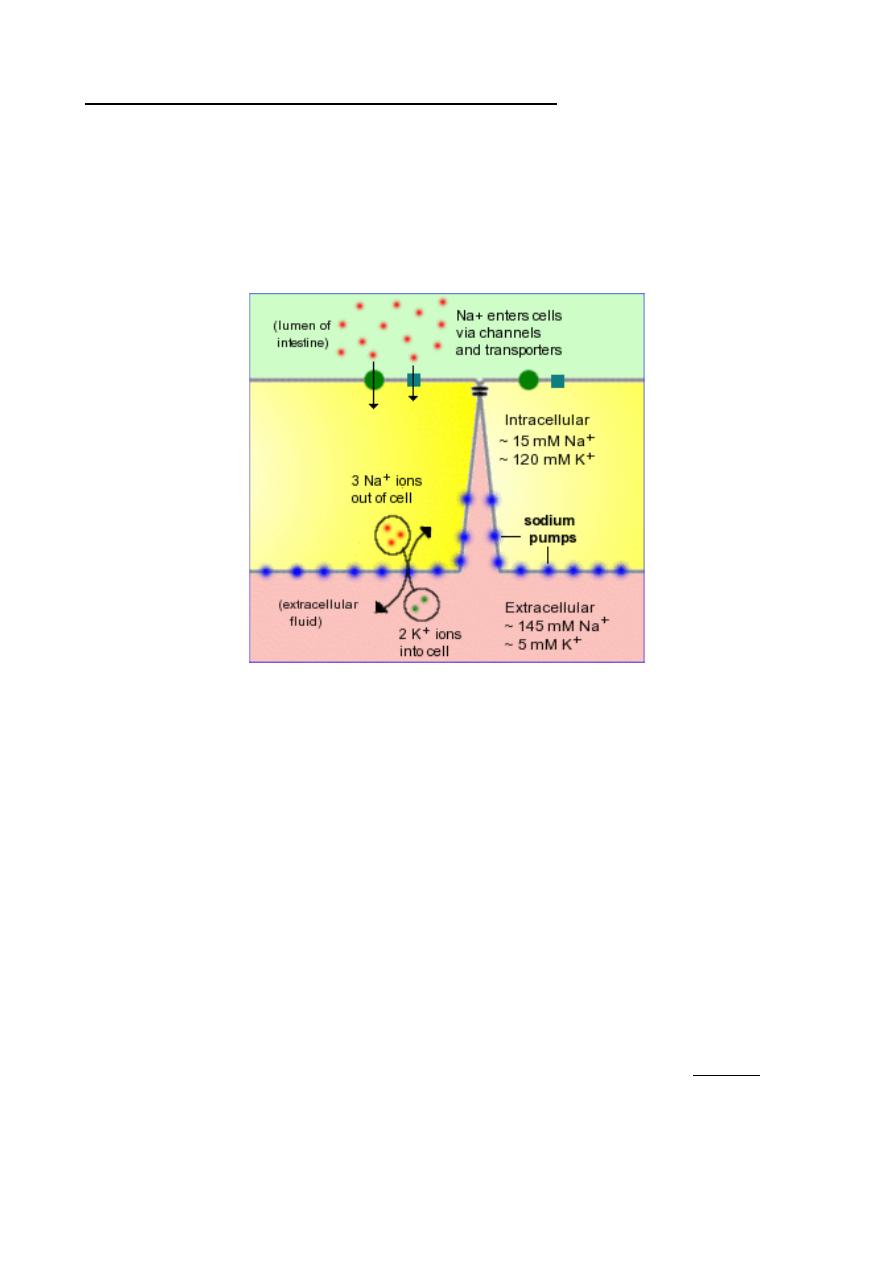

Virtually all nutrients from the diet are absorbed into blood across the mucosa of the small

intestine.To remain viable, all cells are required to maintain a low intracellular

concentration of sodium. In polarized epithelial cells like enterocytes, low intracellular

sodium is maintained by a large number of Na

+

/K

+

ATPases – (sodium pumps) -

embedded in the basolateral membrane. These pumps export 3 sodium ions from the cell

in exchange for 2 potassium ions, thus establishing a gradient of both charge and sodium

concentration across the basolateral membrane.

Aside from the electrochemical gradient of sodium, several other concepts are required to

understand absorption in the small intestine. Also, dietary sources of protein, carbohydrate

and fat must all undergo the final stages of chemical digestion just prior to absorption of,

for example, amino acids, glucose and fatty acids.

•

Water and electrolytes

•

Carbohydrates, after digestion to monosaccharides

•

Proteins, after digestion to small peptides and amino acids

•

Neutral fat, after digestion to monoglyceride and free fatty acids

1) Absorption of Water and Electrolytes

The small intestine must absorb massive quantities of water. A normal person takes in

roughly 1 to 2 liters of dietary fluid every day. On top of that, another 6 to 7 liters of fluid is

received by the small intestine daily as secretions from salivary glands, stomach,

pancreas, liver and the small intestine itself.

By the time the ingesta enters the large intestine, approximately 80% of this fluid has been

absorbed. Net movement of water across cell membranes always occurs by osmosis, and

the fundamental concept needed to understand absorption in the small gut is that

absorption of water is absolutely dependent on absorption of solutes, particularly sodium:

Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

•

Sodium is absorbed into the cell by several mechanisms, but chief among them is

by co-transport with glucose and amino acids - this means that efficient sodium

absorption is dependent on absorption of these organic solutes.

•

Absorbed sodium is rapidly exported from the cell via sodium pumps - when a lot of

sodium is entering the cell, a lot of sodium is pumped out of the cell, which

establishes a high osmolarity in the small intercellular spaces between adjacent

enterocytes.

•

Water diffuses in response to the osmotic gradient established by sodium - in this

case into the intercellular space. It seems that the bulk of the water absorption is

transcellular, but some also diffuses through the tight junctions.

•

Water, as well as sodium, then diffuses into capillary blood within the villus.

Water is thus absorbed into the intercellular space by diffusion down an osmotic gradient.

However, looking at the process as a whole, transport of water from lumen to blood is

often against an osmotic gradient - this is important because it means that the intestine

can absorb water into blood even when the osmolarity in the lumen is higher than

osmolarity of blood.

2) Absorption of Monosaccharides

Monosaccharides, are only rarely found in normal diets. Rather, they are derived by

enzymatic digestion of more complex carbohydrates within the digestive tube.

Particularly important dietary carbohydrates include starch and disaccharides such as

lactose and sucrose. None of these molecules can be absorbed for the simple reason that

they cannot cross cell membranes unaided and, unlike the situation for monosaccharides,

there are no transporters to carry them across.

Brush Border Hydrolases Generate Monosaccharides

Polysaccharides and disaccharides must be digested to monosaccharides prior to

absorption and the key players in these processes are the brush border hydrolases, which

include maltase, lactase and sucrase. Dietary lactose and sucrose are "ready" for

digestion by their respective brush border enzymes. Starch, as discussed previously, is

first digested to maltose by amylase in pancreatic secretions and, saliva.

Dietary lactose and sucrose, and maltose derived from digestion of starch, diffuse in the

small intestinal lumen and come in contact with the surface of absorptive epithelial cells

covering the villi where they engage with brush border hydrolases:

•

maltase cleaves maltose into two molecules of glucose

•

lactase cleaves lactose into a glucose and a galactose

•

sucrase cleaves sucrose into a glucose and a fructose

Glucose and galactose are taken into the enterocyte by cotransport with sodium using the

same transporter. Fructose enters the cell from the intestinal lumen via facilitated diffusion

through another transporter.

Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

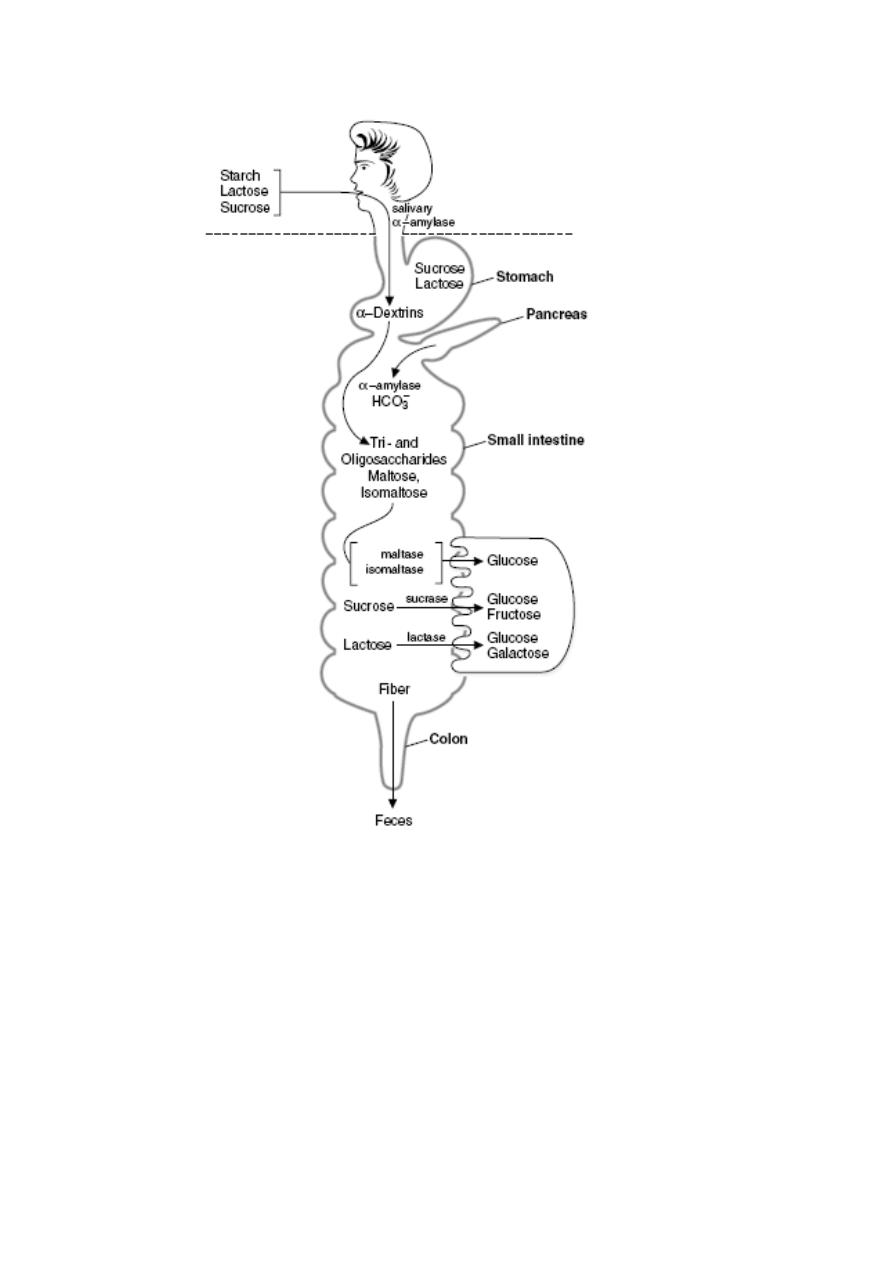

Overview of carbohydrate digestion. Digestion of the carbohydrates occurs first,

followed by absorption of monosaccharides. Subsequent metabolic reactions occur after

the sugars are absorbed.

Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

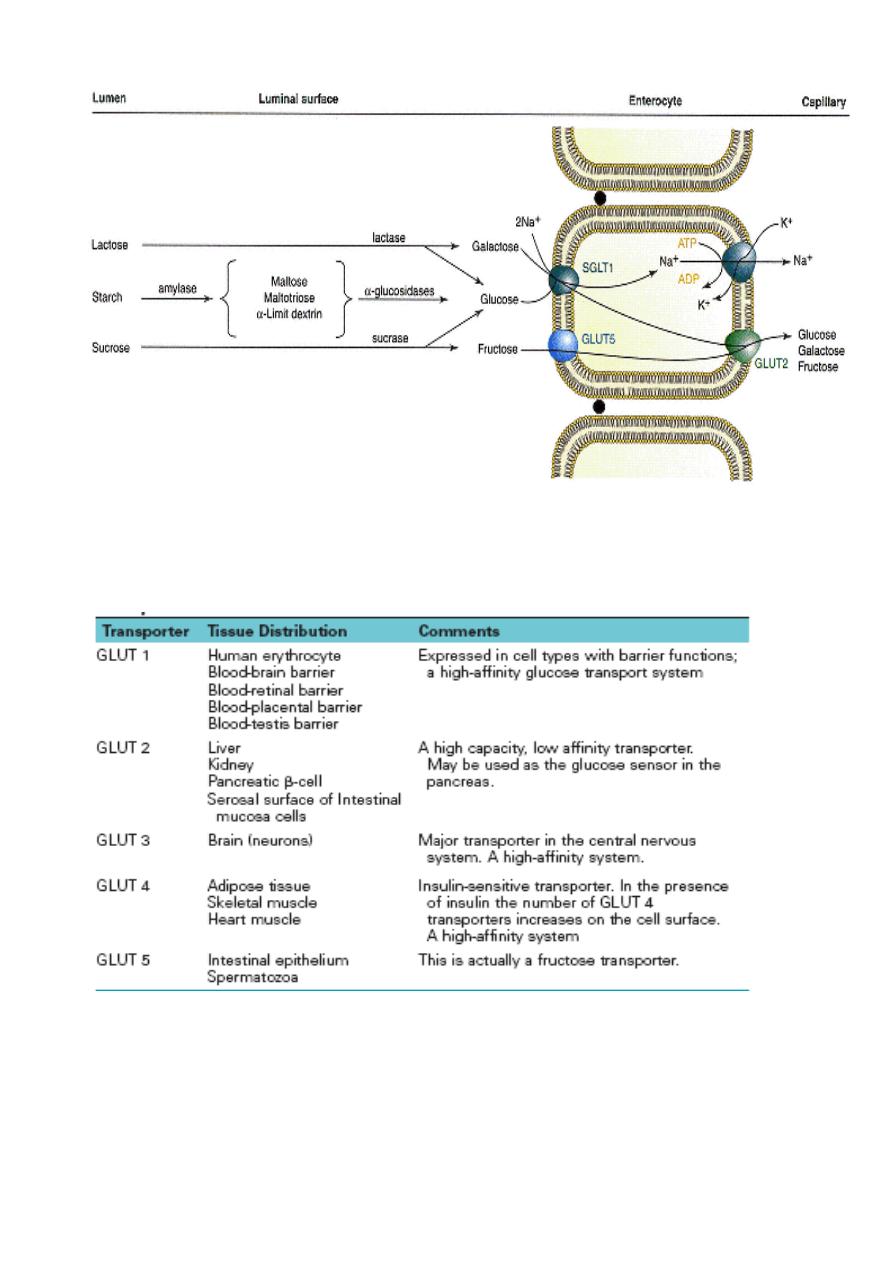

Absorption of Glucose and other

Monosaccharides:

Transport across the Intestinal Epithelium

Absorption of glucose entails transport from the

intestinal lumen, across the epithelium and into

blood. The transporter that carries glucose and

galactose into the enterocyte is the sodium-

dependent hexose transporter, known more

formally as SGLUT-1. As the name indicates, this

molecule transports both glucose and sodium ion

into the cell and in fact, will not transport either

alone.

The essence of transport by the sodium-

dependent hexose transporter involves a series of

conformational changes induced by binding and

release of sodium and glucose, and can be

summarized as follows:

1. the transporter is initially oriented facing

into the lumen - at this point it is capable of

binding sodium, but not glucose

2. sodium binds, inducing a conformational

change that opens the glucose-binding

pocket

3. glucose binds and the transporter reorients

in the membrane such that the pockets

holding sodium and glucose are moved

inside the cell

4. sodium dissociates into the cytoplasm, causing glucose binding to destabilize

5. glucose dissociates into the cytoplasm and the unloaded transporter reorients back

to its original, outward-facing position

Fructose is not co-transported with sodium. Rather it enters the enterocyte by another

hexose transporter (GLUT5).

Once inside the enterocyte, glucose and sodium must be exported from the cell into blood.

Sodium is rapidly shuttled out in exchange for potassium by the battery of sodium pumps

on the basolateral membrane, this process maintains the electrochemical gradient across

the epithelium. The massive transport of sodium out of the cell establishes the osmotic

gradient responsible for absorption of water.

Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

Na_-dependent and facilitative transporters in the intestinal epithelial cells. Both glucose and fructose are

transported by the facilitated glucose transporters on the luminal and serosal sides of the absorptive cells.

Glucose and galactose are transported by the Na_-glucose cotransporters on the luminal (mucosal) side of

the absorptive cells.

Properties of the GLUT 1-GLUT 5 Isoforms of the Glucose Transport Proteins

Genetic techniques have identified additional GLUT transporters (GLUT 7-12), but the role of these

transporters has not yet been fully described

Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

CLINICAL CORRELATION

Disaccharidase Deficiency

Intestinal disaccharidase deficiencies are encountered relatively frequently in humans. Deficiency can

be present in one enzyme or several enzymes for a variety of reasons (genetic defect, physiological

decline with age, or the result of "injuries" to the mucosa). Of the disaccharidases, lactase is the most

common enzyme with an absolute or relative deficiency, which is experienced as milk intolerance. The

consequences of an inability to hydrolyze lactose in the upper small intestine are inability to absorb

lactose and bacterial fermentation of ingested lactose in the lower small intestine. Bacterial

fermentation results in the production of gas (distension of gut and flatulence) and osmotically active

solutes that draw water into the intestinal lumen (diarrhea). The lactose in yogurt has already been

partially hydrolyzed during the fermentation process of making yogurt. Thus individuals with lactase

deficiency can often tolerate yogurt better than unfermented dairy products. The enzyme lactase is

commercially available to pretreat milk so that the lactose is hydrolyzed

.

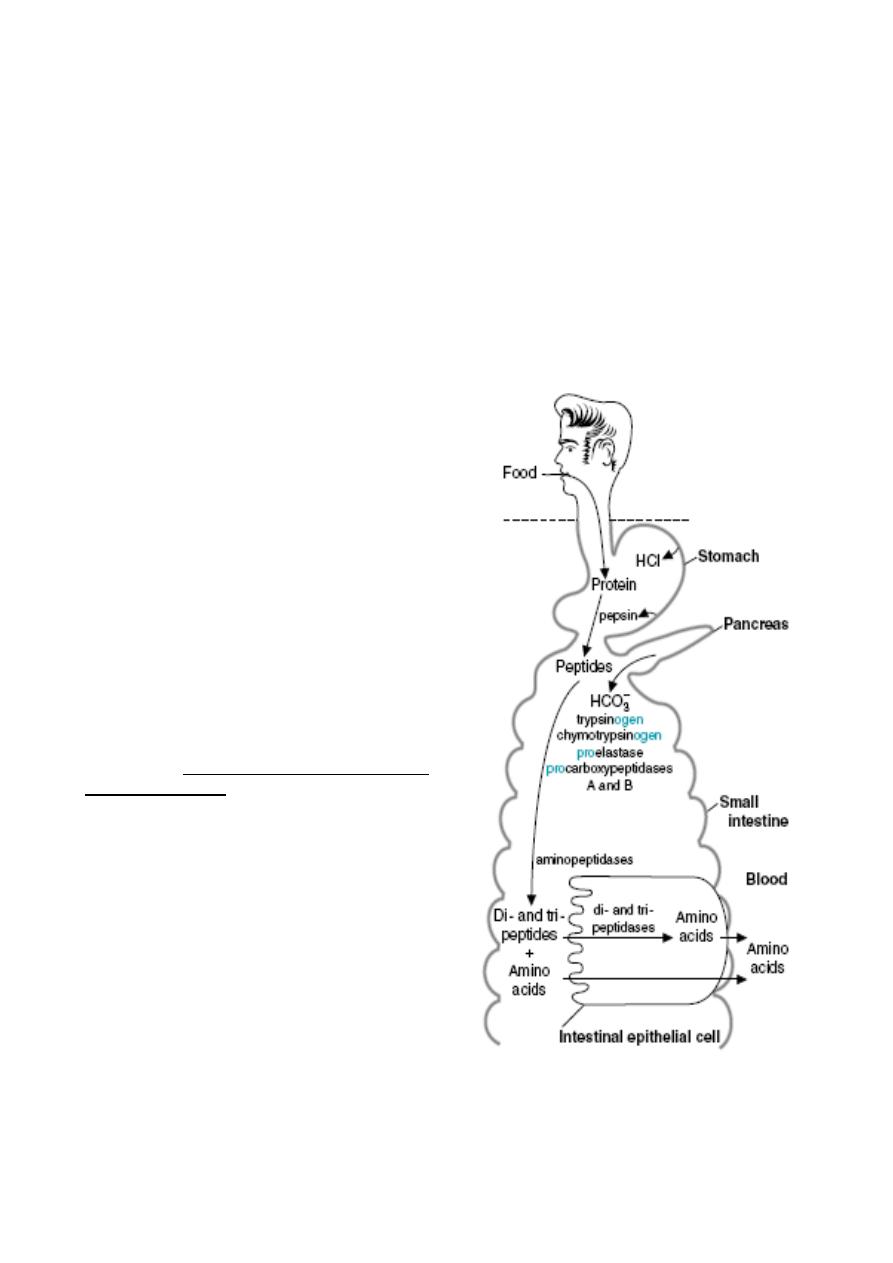

3) Absorption of Amino Acids and

Peptides

Dietary proteins are, with very few

exceptions, not absorbed. Rather, they

must be digested into amino acids or di-

and tripeptides first, through the action of

gastric and pancreatic proteases. The

brush border of the small intestine is

equipped with a family of peptidases. Like

lactase and maltase, these peptidases are

integral membrane proteins rather than

soluble enzymes. They function to further

the hydrolysis of lumenal peptides,

converting them to free amino acids and

very small peptides. These endproducts of

digestion, formed on the surface of the

enterocyte, are ready for absorption.

a) Absorption of Amino Acids

The mechanism by which amino acids are

absorbed is conceptually identical to that of

monosaccharides. The lumenal plasma

membrane of the absorptive cell bears at

least four sodium-dependent amino acid

transporters - one each for acidic, basic,

neutral and amino acids. These

transporters bind amino acids only after

binding sodium. The fully loaded transporter

then undergoes a conformational change

that dumps sodium and the amino acid into

the cytoplasm, followed by its reorientation

back to the original form.

Thus, absorption of amino acids is also

absolutely dependent on the

electrochemical gradient of sodium across

the epithelium. Further, absorption of amino acids, like that of monosaccharides,

contributes to generating the osmotic gradient that drives water absorption.

The basolateral membrane of the enterocyte contains additional transporters which export

amino acids from the cell into blood. These are not dependent on sodium gradients.

Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

CLINICAL CORRELATION

1.

Neutral Amino Aciduria (Hartnup Disease)

Transport functions, like enzymatic functions, are subject to modification by mutations. An example

of a genetic lesion in epithelial amino acid transport is Hartnup disease, named after the family in

which the disease entity resulting from the defect was first recognized. The disease is

characterized by the inability of renal and intestinal epithelial cells to absorb neutral amino acids

from the lumen. In the kidney, in which plasma amino acids reach the lumen of the proximal tubule

through the ultrafiltrate, the inability to reabsorb amino acids manifests itself as excretion of amino

acids in the urine (amino aciduria). The intestinal defect results in malabsorption of free amino

acids from the diet. Therefore the clinical symptoms of patients with this disease are mainly those

due to essential amino acid and nicotinamide deficiencies. The pellagra-like features are explained

by a deficiency of tryptophan, which serves as precursor for nicotinamide. Investigations of patients

with Hartnup disease revealed the existence of intestinal transport systems for di- or tripeptides,

which are different from the ones for free amino acids. The genetic lesion does not affect transport

of peptides, which remains as a pathway for absorption of protein digestion products

Q:

Why do patients with cystinuria and Hartnup disease have a hyperaminoaciduria without an

associated hyperaminoacidemia?

A:

Patients with cystinuria and Hartnup disease have defective transport proteins in both the

intestine and the kidney. These patients do not absorb the affected amino acids at a normal rate

from the digestive products in the intestinal lumen. They also do not readily resorb these amino

acids from the glomerular filtrate into the blood. Therefore, they do not have a hyperaminoacidemia

(a high concentration in the blood). Normally, only a few percent of the amino acids that enter the

glomerular filtrate are excreted in the urine; most are resorbed. In these diseases, much larger

amounts of the affected amino acids are excreted in the urine, resulting in a hyperaminoaciduria.

2.

Kwashiorkor,

A common problem of children in Third World countries, is caused by a deficiency of protein in a

diet that is adequate in calories. Children with kwashiorkor suffer from muscle wasting and a

decreased concentration of plasma proteins, particularly albumin. The result is an increase in

interstitial fluid that causes edema and a distended abdomen that make the children appear

“plump”. The muscle wasting is caused by the lack of essential amino acids in the diet; existing

proteins must be broken down to produce these amino acids for new protein synthesis. These

problems may be compounded by a decreased ability to produce digestive enzymes and new

intestinal epithelial cells because of a decreased availability of amino acids for the synthesis of new

proteins.

b) Absorption of Peptides

There is virtually no absorption of peptides longer than four amino acids. However, there is

abundant absorption of di- and tripeptides in the small intestine. These small peptides are

absorbed into the small intestinal epithelial cell by cotransport with H

+

ions via a transporter called

PepT1.

Once inside the enterocyte, the vast bulk of absorbed di- and tripeptides are digested into amino

acids by cytoplasmic peptidases and exported from the cell into blood. Only a very small number of

these small peptides enter blood intact.

c) Absorption of Intact Proteins

Absorption of intact proteins occurs only in a few circumstances. Normal" enterocytes do not have

transporters to carry proteins across the plasma membrane and they certainly cannot permeate

tight junctions.

One important exception is that for a very few days after birth, neonates have the ability to absorb

intact proteins. This ability, which is rapidly lost, is of immense importance because it allows the

newborn animal to acquire passive immunity by absorbing immunoglobulins in colostral milk. The

small intestine rapidly loses the capacity to absorb intact proteins.

Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

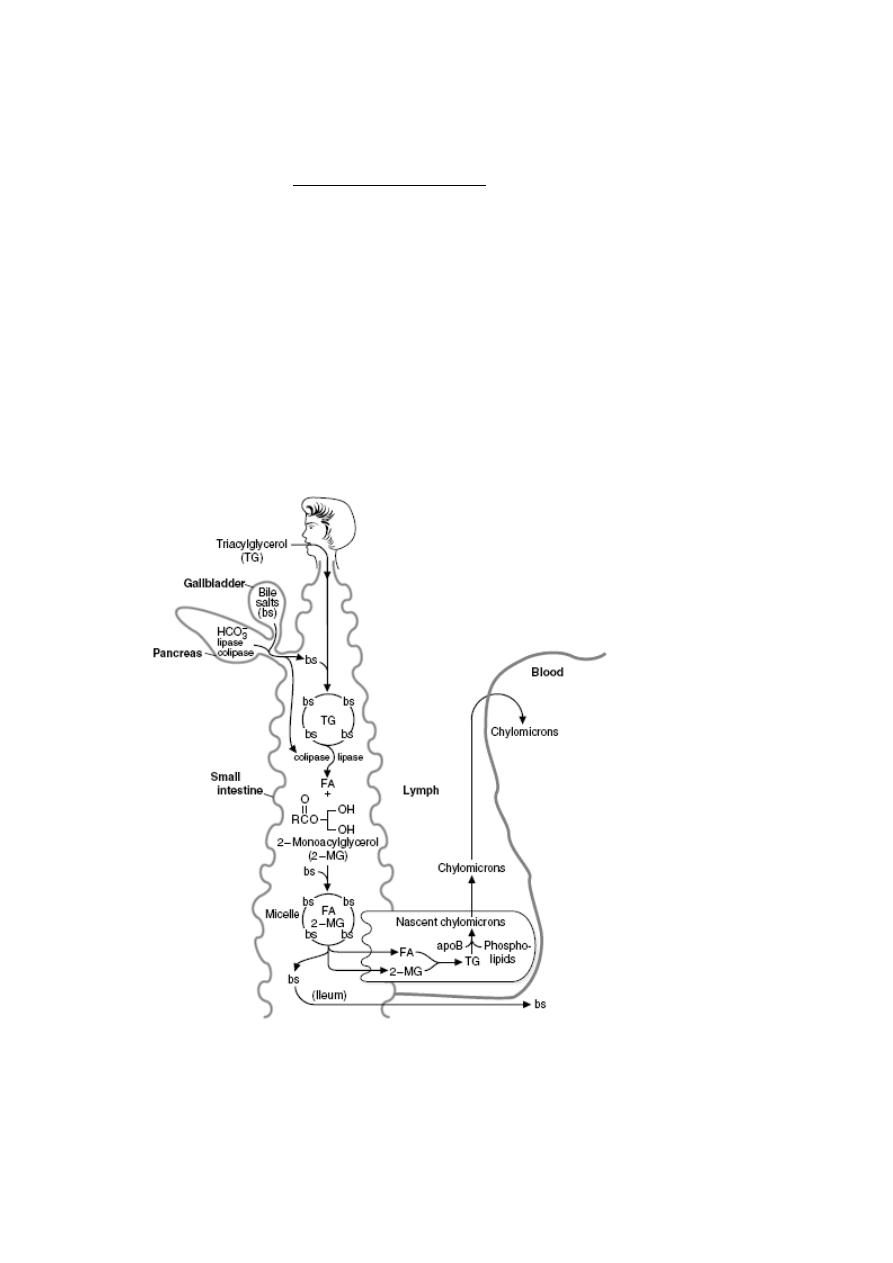

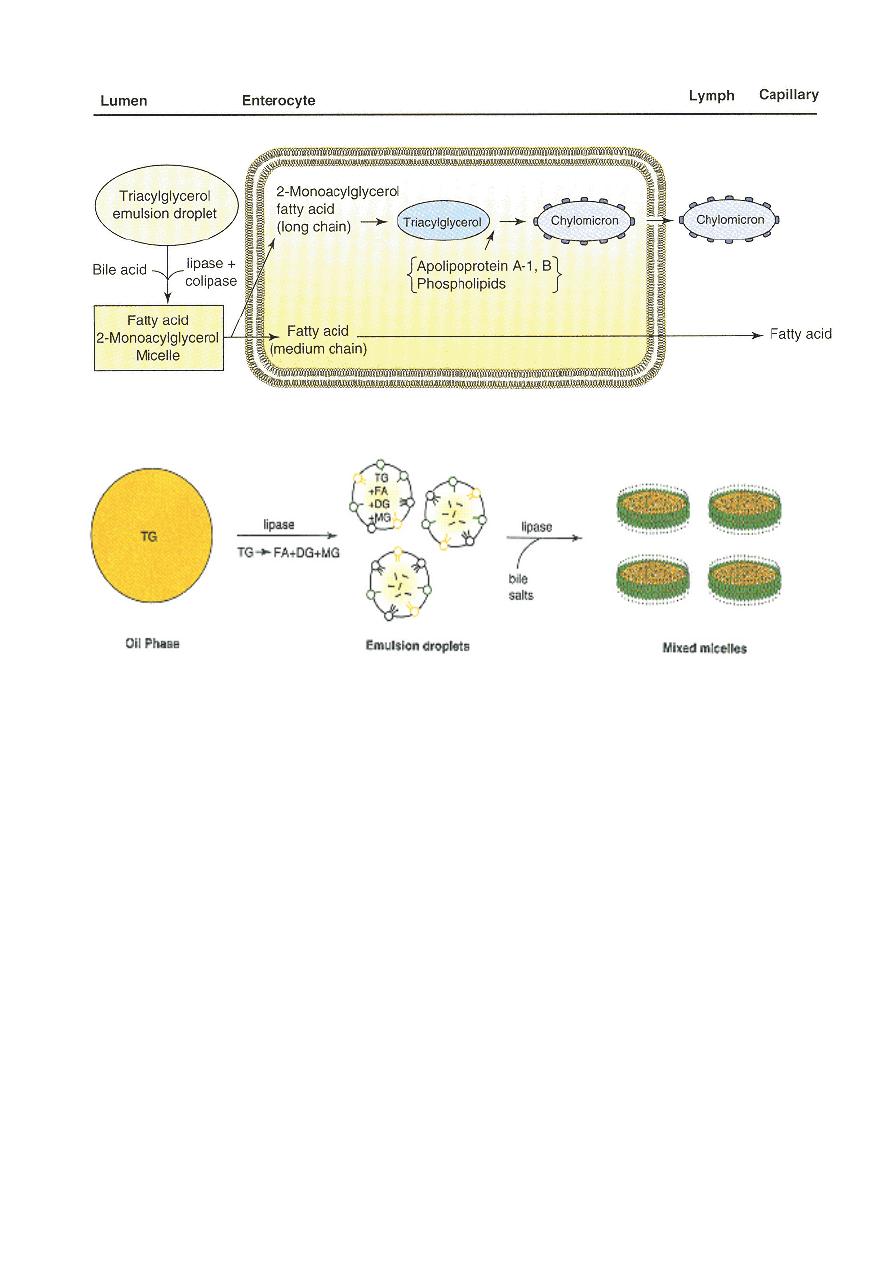

4) Absorption of Lipids

The bulk of dietary lipid is neutral fat or triglyceride, composed of a glycerol backbone with

each carbon linked to a fatty acid. Additionally, most foodstuffs contain phospholipids,

sterols like cholesterol and many minor lipids, including fat-soluble vitamins. In order for

the triglyceride to be absorbed, two processes must occur:

•

Large aggregates of dietary triglyceride, which are virtually insoluble in an aqueous

environment, must be broken down physically and held in suspension - a process

called emulsification.

•

Triglyceride molecules must be enzymatically digested to yield monoglyceride and

fatty acids, both of which can efficiently diffuse into the enterocyte

The key players in these two transformations are bile salts and pancreatic lipase, both of which are

mixed with chyme and act in the lumen of the small intestine.

Digestion of triacylglycerols in the intestinal lumen. TG _ triacylglycerol; bs _ bile

salts; FA _ fatty acid; 2-MG _ 2-monoacylglycerol

Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

Digestion and absorption of lipids

Changes in physical state during triacylglycerol digestion.

Abbreviations: TG, triacylglycerol; DG, diacylglycerol; MG, monoacylglycerol; FA, fatty acid

CLINICAL CORRELATION

A-

β

-Lipoproteinemia

A-b-lipoproteinemia is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by the absence of all lipoproteins

containing apo-

β

-lipoprotein, that is, chylomicrons, very low density lipoproteins (VLDLs), and low density

lipoproteins (LDLs). Serum cholesterol is extremely low. This defect is associated with severe malabsorption

of triacylglycerol and lipid-soluble vitamins (especially tocopherol and vitamin E) and accumulation of apo B

in enterocytes and hepatocytes. The defect does not appear to involve the gene for apo B, but rather one of

several proteins involved in processing of apo B in liver and intestinal mucosa, or in assembly and secretion

of triacylglycerol-rich lipoproteins, that is, chylomicrons and VLDLs from these tissues, respectively.

Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

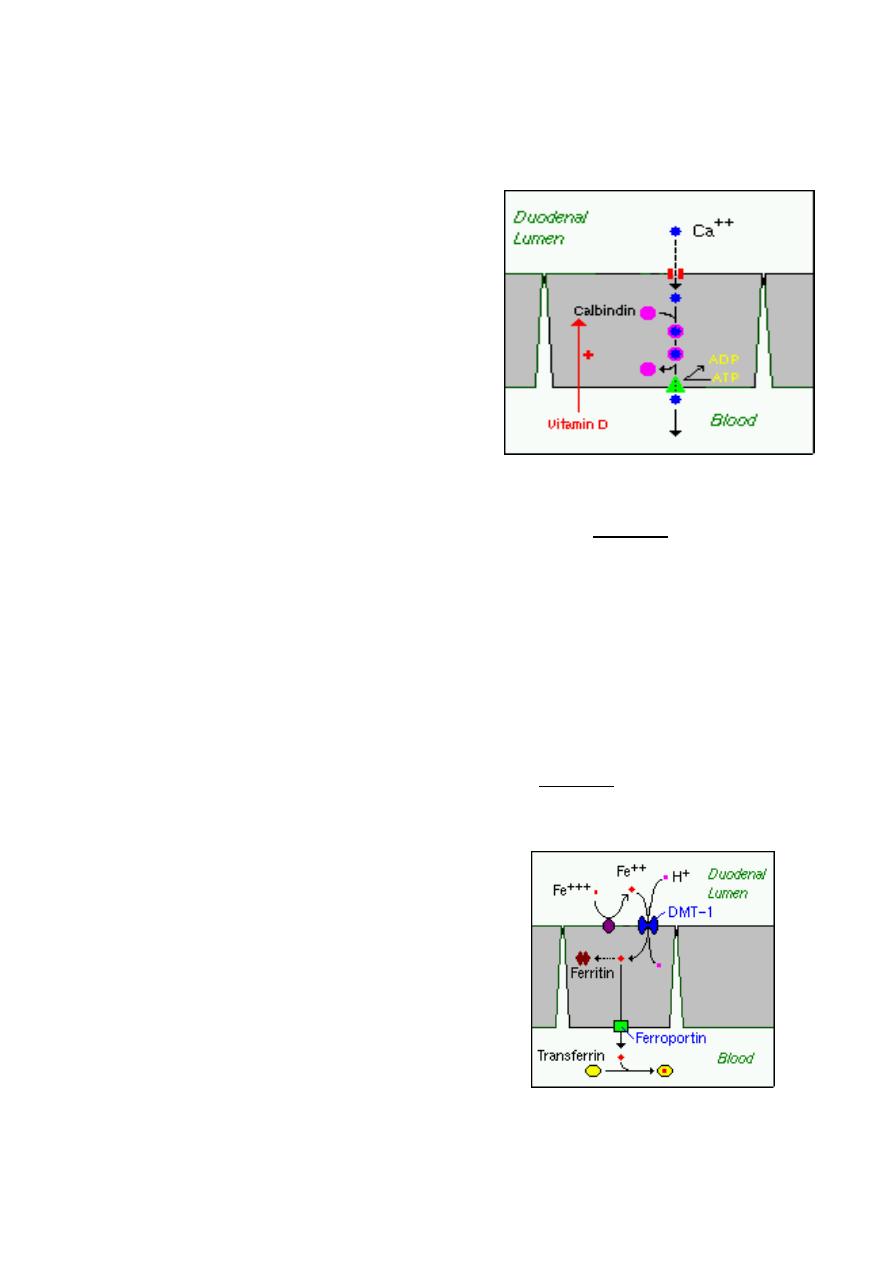

5) Absorption of Minerals and Metals

The vast bulk of mineral absorption occurs in the small intestine. The best-studied

mechanisms of absorption are clearly for calcium

and iron, deficiencies of which are significant health

problems throughout the world.

a) Calcium

The quantity of calcium absorbed in the intestine is

controlled by how much calcium has been in the diet

during recent periods of time. Calcium is absorbed

by two distinct mechanisms:

1. Active, transcellular absorption occurs only in the

duodenum when calcium intake has been low. This

process involves import of calcium into the enterocyte, transport across the cell, and

export into extracellular fluid and blood. The rate limiting step in transcellular calcium

absorption is transport across the epithelial cell, which is greatly enhanced by the carrier

protein calbindin, the synthesis of which is totally dependent on vitamin D.

2. Passive, paracellular absorption occurs in the jejunum and ileum, and, to a much lesser

extent, in the colon when dietary calcium levels have been moderate or high. In this case,

ionized calcium diffuses through tight junctions into the basolateral spaces around

enterocytes, and hence into blood. Such transport depends on having higher

concentrations of free calcium in the intestinal lumen than in blood.

b) Phosphorus

Phosphorus is predominantly absorbed as inorganic phosphate in the upper small

intestine. Phosphate is transported into the epithelial cells by cotransport with sodium, and

expression of this (or these) transporters is enhanced by vitamin D.

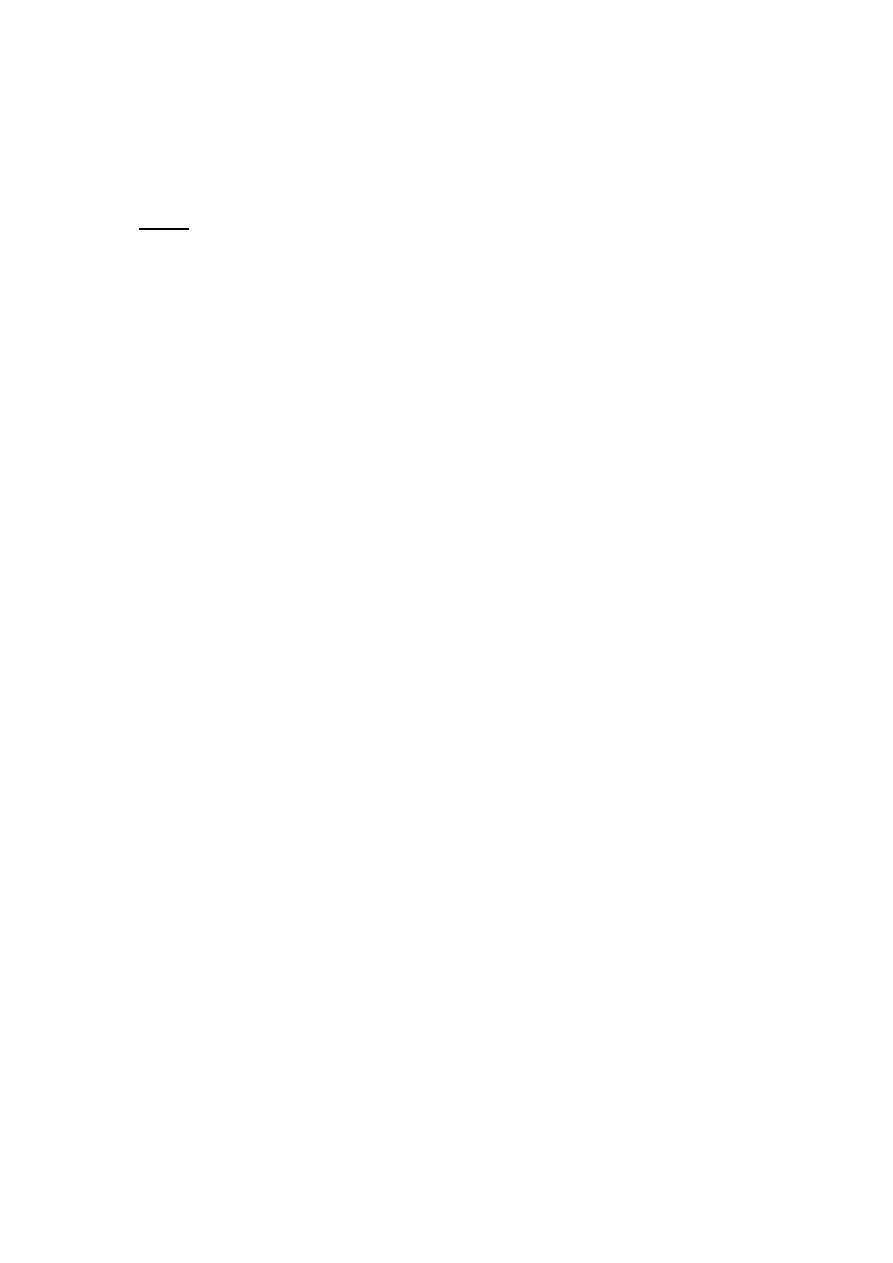

c) Iron

Iron homeostasis is regulated at the level of intestinal

absorption, and it is important that adequate but not

excessive quantities of iron be absorbed from the diet.

Inadequate absorption can lead to iron-deficiency

disorders such as anemia. On the other hand,

excessive iron is toxic because mammals do not have a

physiologic pathway for its elimination.

Iron is absorbed by villus enterocytes in the proximal

duodenum. Efficient absorption requires an acidic

environment.

Ferric iron (Fe+++) in the duodenal lumen is reduced to its ferrous form through the action

of a brush border ferrireductase. Iron is then co transported with a proton into the

Lecture 5

Tuesday 2/10/2012

Prof. Dr. H.D.El-Yassin

2012

enterocyte via the divalent metal transporter DMT-1. This transporter is not specific for

iron, and also transports many divalent metal ions.

Once inside the enterocyte, iron follows one of two major pathways:

•

Iron abundance states: iron within the enterocyte is trapped by incorporation into

ferritin and hence, not transported into blood. When the enterocyte dies and is

shed, this iron is lost.

•

Iron limiting states: iron is exported out of the enterocyte via a transporter

(ferroportin) located in the basolateral membrane. It then binds to the iron-carrier

transferrin for transport throughout the body.

d) Copper

There appear to be two processes responsible for copper absorption:

i) a rapid, low capacity system and

ii) a slower, high capacity system, which may be similar to the two processes seen

with calcium absorption.

Many of the molecular details of copper absorption remain to be elucidated. Inactivating

mutations in the gene encoding an intracellular copper ATPase have been shown

responsible for the failure of intestinal copper absorption in Menkes disease.

A number of dietary factors have been shown to influence copper absorption. For

example, excessive dietary intake of either zinc or molybdenum can induce secondary

copper deficiency states.

e) Zinc

Zinc homeostasis is largely regulated by its uptake and loss through the small intestine.

Although a number of zinc transporters and binding proteins have been identified in villus

epithelial cells, a detailed picture of the molecules involved in zinc absorption is not yet in

hand.

A number of nutritional factors have been identified that modulate zinc absorption. Certain

animal proteins in the diet enhance zinc absorption. Phytates from dietary plant material

(including cereal grains, corn, rice) chelate zinc and inhibit its absorption. Subsistence on

phytate-rich diets is thought responsible for a considerable fraction of human zinc

deficiencies.