Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

1

Biochemistry of Hormones

A case oriented approach

1. Lecture 1: Introduction to the Biochemistry of hormones and their mechanism of actions.

Thursday

16/2

2. Lecture 2: Introduction to the Biochemistry of hormones and their mechanism of actions.

Sunday

19/2

3. Lecture 3: Biochemistry and disorders of hormones of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland

(hypothalamus- pituitary axis).

Thursday

23/2

4. Lecture 4: Biochemistry and disorders of hormones of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland

(hypothalamus- pituitary axis).

Sunday

26/2

5. Lecture 5: Biochemistry and disorders of hormones of the thyroid and parathyroid gland

Sunday

4/3

6. Lecture 6: Biochemistry and disorders of hormones of the pancreas

Thursday

8/3

7. Lecture 7: Biochemistry and disorders of hormones of the adrenal gland

Sunday

11/3

8. Lecture 8: Biochemistry and disorders of hormones of the adipose tissues, heart and kidney

Sunday

18/3

Aim and objective of the above eight lectures is to understand:

1. The functions of hormones and the mechanisms involved in the regulation of their

secretion.

2. The types of receptor-hormone interactions and the specific effect that each type can

be produced in the cell.

3. the hypothalamus- pituitary axis.

4. the biochemistry and disorders of hormones secretion from different glands.

5. and to learn the major causes of endocrine disorders by discussing clinical cases.

References:

1. "Biochemistry" by Lubert Stryer

(textbook)

2. "Textbook of Biochemistry with Clinical Correlations" by T.M.Devlin

(additional reading)

3. "Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews in Biochemistry" by P.C.Champe, R.A.Harvey and

D.R.Ferrier

(additional reading)

4. "Harper's Biochemistry" by R.K.Murray, D.K.Granner, P.A. Mayes and V.W.Rodwell.

(additional reading)

5. "Clinical Laboratory Science Review" By Robert R. Harr

(additional reading)

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

2

INTRODUCTION

TO THE

BIOCHEMISTRY

OF HORMONES

AND THEIR

MECHANISM

OF ACTIONS

2012

Prof. Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

3

Introduction to the Biochemistry of

Hormones and their Mechanism of Actions

Lecture 1

Thursday 16/2/2012

Lecture 2

Sunday 19/2/2012

The endocrine system is one of the two coordinating and integrating systems of the

body. It acts through chemical messengers - hormones –carried in the circulation.

Two systems control all physiologic processes:

•

The nervous system

exerts point-to-point control through nerves, similar to

sending messages by conventional telephone. Nervous control is electrical in

nature and fast.

•

The endocrine system

broadcasts its hormonal messages to essentially all cells

by secretion into blood and extracellular fluid. Like a radio broadcast, it

requires a receiver to get the message - in the case of endocrine messages, cells

must bear a receptor for the hormone being broadcast in order to respond.

Endocrinology is the study of hormones, their receptors and the intracellular

signaling pathways they invoke. Distinct endocrine organs are scattered throughout

the body. These are organs that are largely or at least famously devoted to secretion

of hormones. In addition to the classical endocrine organs, many other cells in the

body secrete hormones. Myocytes in the atria of the heart and scattered epithelial

cells in the stomach and small intestine are examples of what is sometimes called the

"diffuse" endocrine system. If the term hormone is defined broadly to include all

secreted chemical messengers, then virtually all cells can be considered part of the

endocrine system.

•

All pathophysiologic events are influenced by the endocrine milieu: There are

no cell types, organs or processes that are not influenced - often profoundly -

by hormone signaling.

•

All "large" physiologic effects a re mediated by multiple hormones acting in

concert: Normal growth from birth to adulthood, for example, is surely

dependent on growth hormone, but thyroid hormones, insulin-like growth

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

4

factor-1, glucocorticoids and several other hormones are also critically

involved in this process.

•

There are many hormones known and little doubt that others remain to be

discovered.

Hormones, Receptors and Target Cells

1. Classes of Hormones

Knowing the basic structure of a hormone gives a considerable knowledge

about its receptor and mechanism of action.

Like all molecules, hormones are synthesized, exist in a biologically active

state for a time, and then degrade or are destroyed. Having an appreciation

for the "half-life" and mode of elimination of a hormone aids in understanding

its role in physiology and is critical when using hormones as drugs.

Most commonly, hormones are categorized into four structural groups,

with members of each group having many properties in common:

•

Peptides and proteins

•

Amino acid derivatives

•

Steroids

•

Fatty acid derivatives - Eicosanoids

1.

Peptides and Proteins

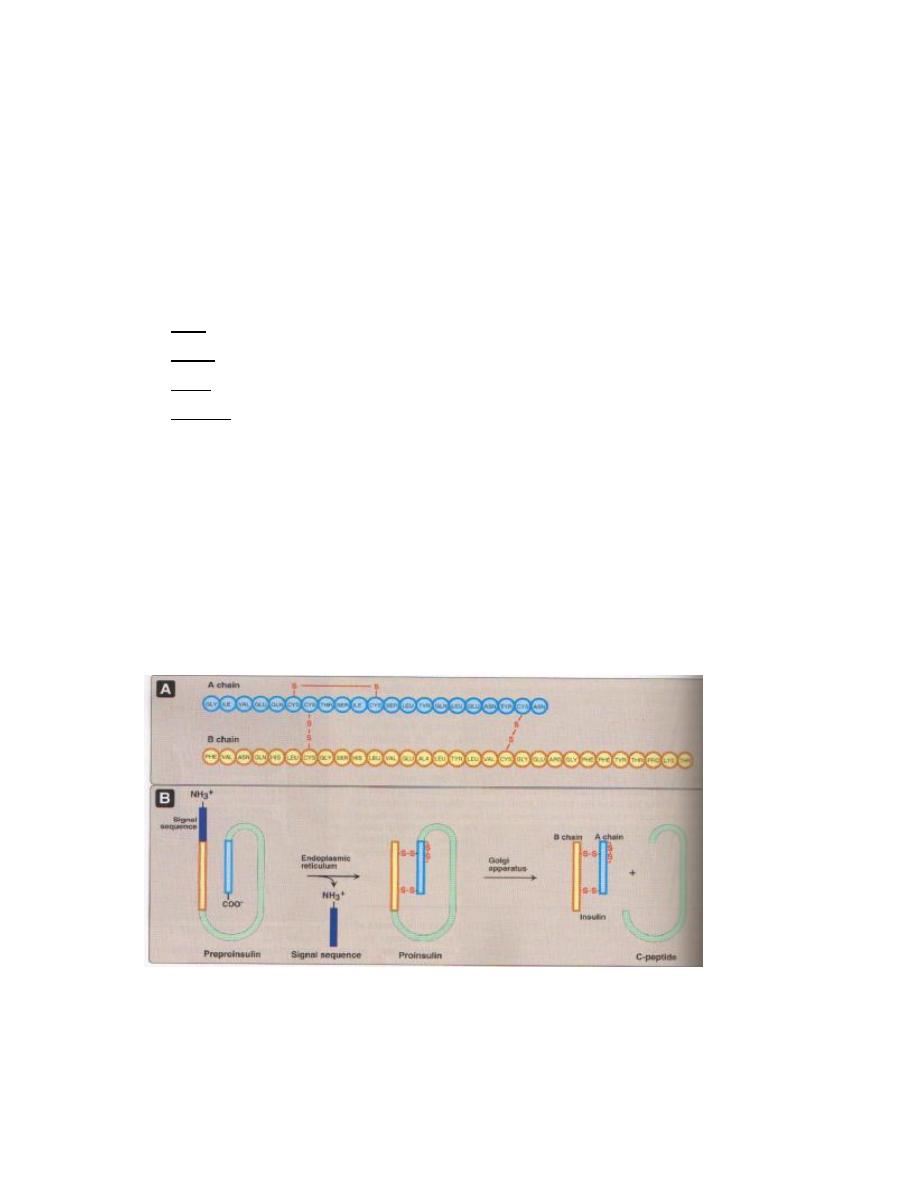

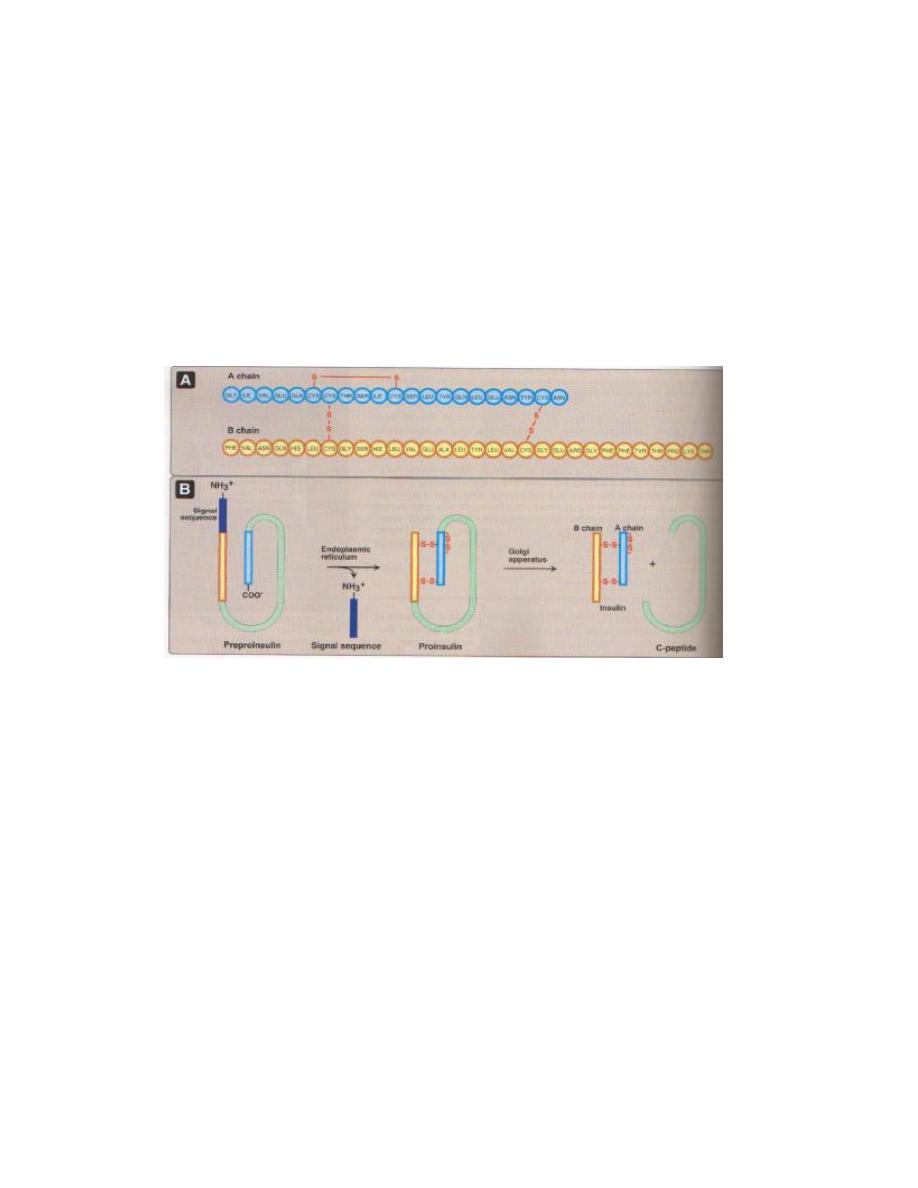

Peptide and protein hormones are products of translation. They vary

considerably in size and post-translational modifications, ranging from

peptides as short as three amino acids to large, multisubunit glycoproteins.

Peptide hormones are synthesized in endoplasmic reticulum, transferred to

the Golgi and packaged into secretory vesicles for export.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

5

They can be secreted by one of two pathways:

•

Regulated secretion: The cell stores hormone in secretory granules

and releases them in "bursts" when stimulated. This is the most

commonly used pathway and allows cells to secrete a large amount of

hormone over a short period of time.

•

Constitutive secretion: The cell does not store hormone, but secretes

it from secretory vesicles as it is synthesized.

Most peptide hormones circulate unbound to other proteins, but exceptions exist; for

example, insulin-like growth factor-1 binds to one of several binding proteins. In general,

the half-life of circulating peptide hormones is only a few minutes.

Several important peptide hormones are secreted from the pituitary gland.

The anterior pituitary secretes:

•

Luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone, which act on the

gonads.

•

prolactin, which acts on the mammary gland,

•

adrenocortiotrpic hormone (ACTH), which acts on the adrenal cortex to

regulate the secretion of glucocorticoids, and

•

growth hormone, which acts on bone, muscle and liver.

The posterior pituitary gland secretes:

•

antidiuretic hormone, also called vasopressin, and

•

oxytocin.

Peptide hormones are produced by many different organs and tissues,

however, including:

•

the heart (atrial-natriuretic peptide (ANP) or atrial natriuretic factor

(ANF))

•

pancreas (insulin and somatostatin),

•

the gastrointestinal tract cholecystokinin, gastrin, and

•

fat stores (leptin)

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

6

Many neurotransmitters are secreted and released in a similar fashion to peptide

hormones, and some 'neuropeptides' may be used as neurotransmitters in the nervous

system in addition to acting as hormones when released into the blood. When a peptide

hormone binds to receptors on the surface of the cell, a second messenger appears in the

cytoplasm.

2.

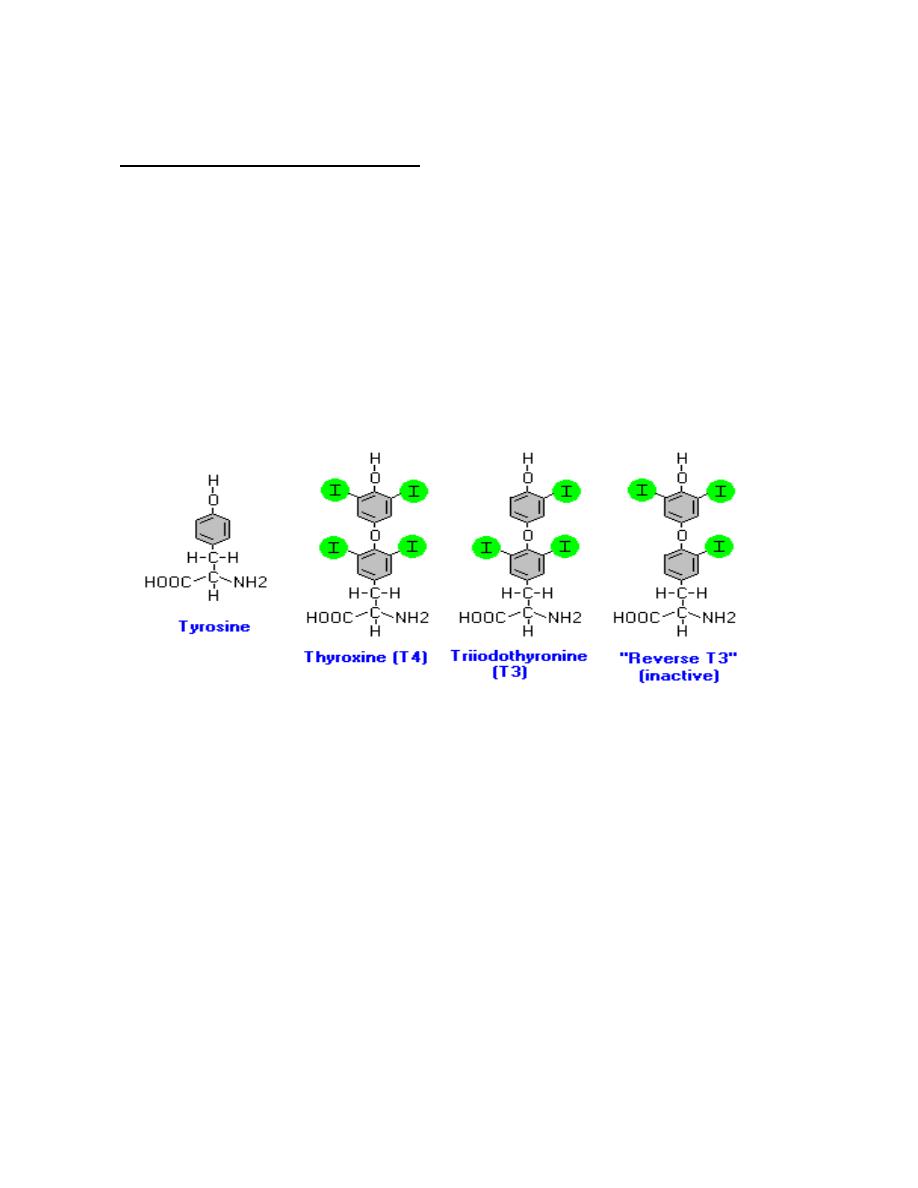

Amino acid derivatives

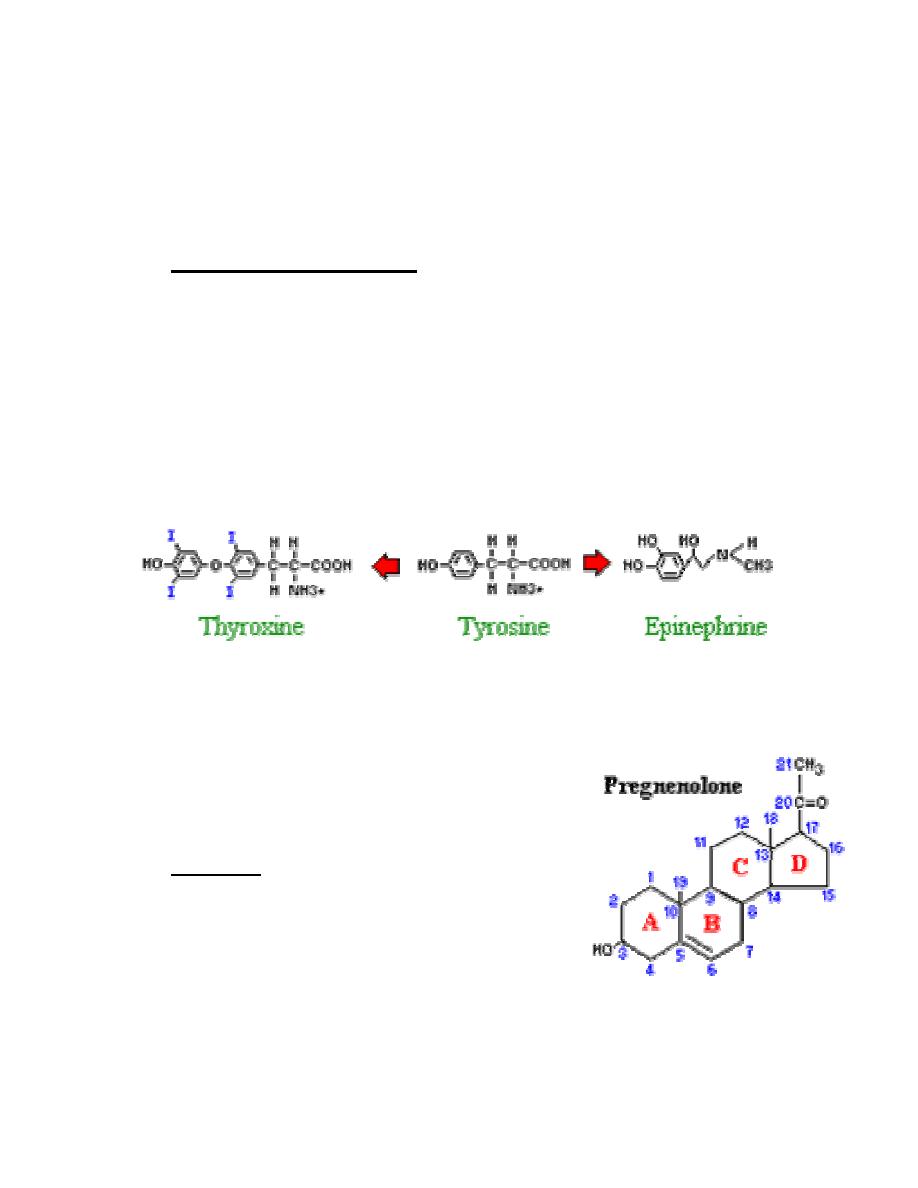

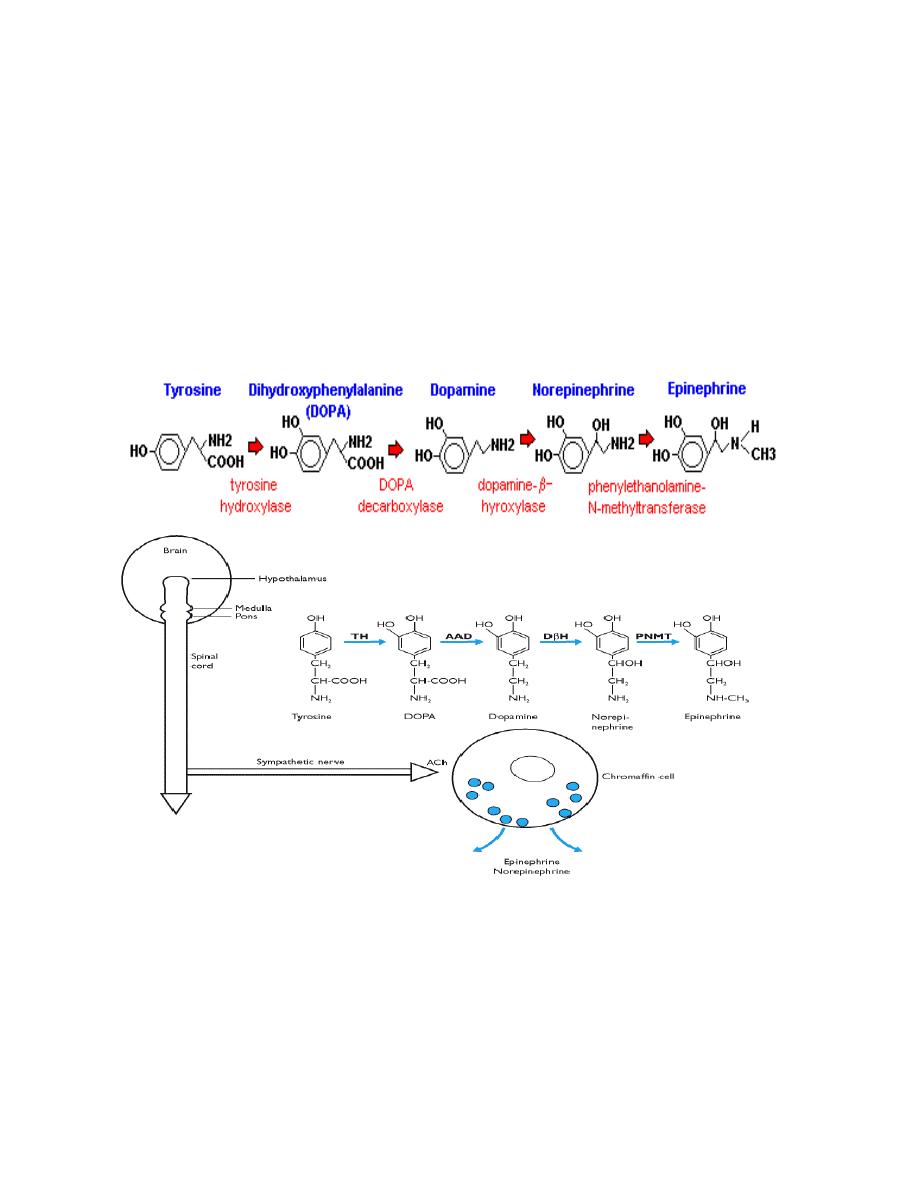

There are two groups of hormones derived from the amino acid

tyrosine:

•

Thyroid hormones are basically a "double" tyrosine with the critical

incorporation of 3 or 4 iodine atoms.

•

Catecholamines include epinephrine and norepinephrine, which are

used as both hormones and neurotransmitters.

The circulating half-life of thyroid hormones is on the order of a few days.

Two other amino acids are used for synthesis of hormones:

•

Tryptophan is the precursor to serotonin and

the pineal hormone melatonin

•

Glutamic acid is converted to histamine

3.

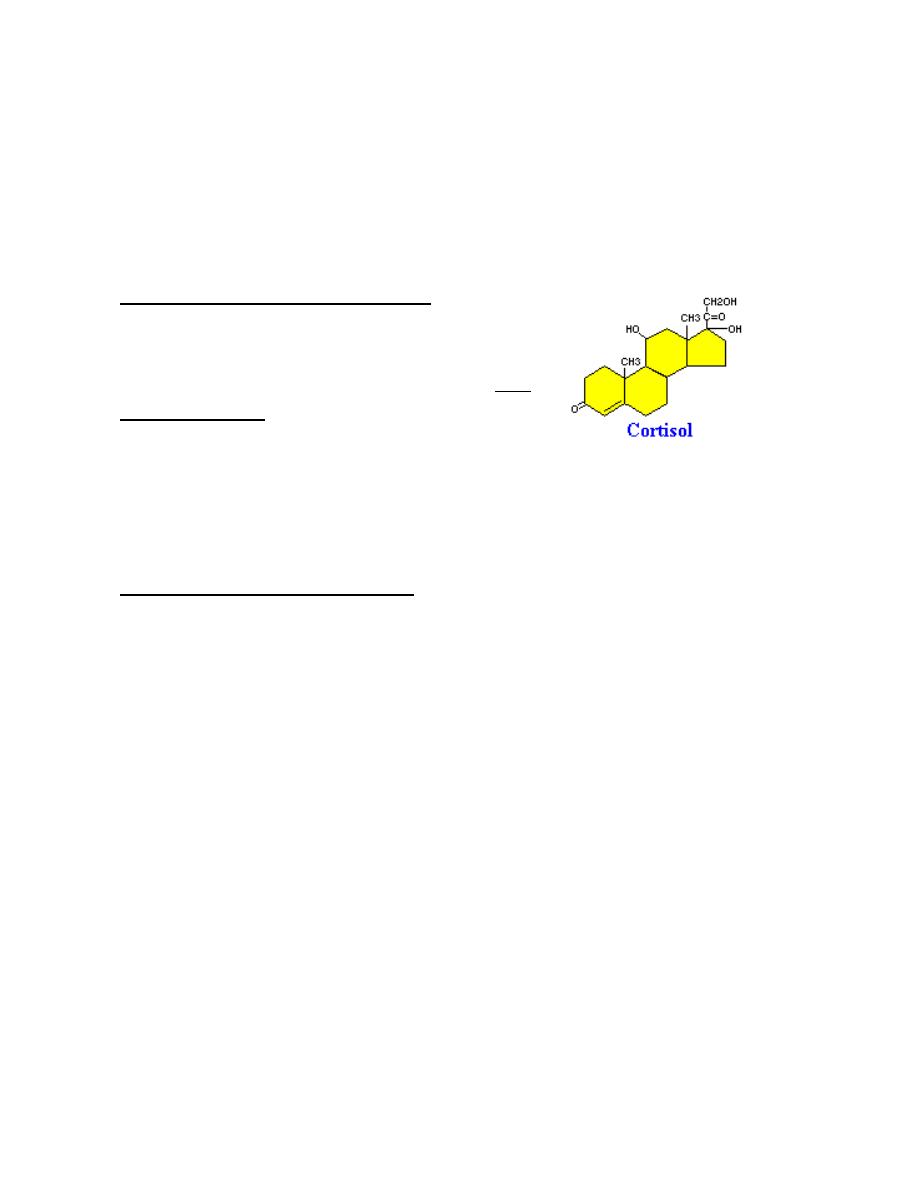

Steroids

Steroids are lipids and, more specifically,

derivatives of cholesterol. Examples include the

sex steroids such as testosterone and adrenal

steroids such as cortisol. The first and rate-limiting step in the synthesis of all

steroid hormones is conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone, which

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

7

demonstrate the system of numbering rings and carbons for identification of

different steroid hormones.

Pregnenolone is formed on the inner membrane of mitochondria then shuttled

back and forth between mitochondrion and the endoplasmic reticulum for

further enzymatic transformations involved in synthesis of derivative steroid

hormones. Newly synthesized steroid hormones are rapidly secreted from the

cell, with little if any storage. Increases in secretion reflect accelerated rates

of synthesis. Following secretion, all steroids bind to some extent to plasma

proteins.

Steroid hormones are typically eliminated by inactivating metabolic

transformations and excretion in urine or bile.

4. Fatty Acid Derivatives - Eicosanoids

Eicosanoids are a large group of molecules derived from

polyunsaturated fatty acids. The principal groups of

hormones of this class are prostaglandins, prostacyclins,

leukotrienes and thromboxanes.

Arachadonic acid is the most abundant precursor for these hormones. Stores

of arachadonic acid are present in membrane lipids and released through the

action of various lipases.

A great variety of cells produce prostaglandins , including those of the liver,

kidneys, heart, lungs, thymus gland, pancreas, brain, and reproductive

organs. In contrast to hormones, prostaglandins usually act locally, affecting

only adjacent cells or the very cell that secreted it.

Prostaglandins are potent and are presented in very small quantities. They

are not stored in cells but rather are synthesized just before release. These

hormones are rapidly inactivated by being metabolized, and are typically

active for only a few seconds

Q

How are prostaglandins different from hormones?

A

They do not use the blood for transportation, they act locally and are synthesized in

cell membrane just before release

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

8

2.

Receptors and Target Cells

A given hormone usually affects only a limited number of cells, which

are called target cells. A target cell responds to a hormone because it

bears receptors for the hormone.

Hormone receptors are found either exposed on the surface of the cell or

within the cell, depending on the type of hormone. In very basic terms,

binding of hormone to receptor triggers a cascade of reactions within the cell

that affects function.

Hormone receptors have two essential qualities:

1. The receptor must be able to recognize a unique binding site within the

hormone in order to discriminate between the hormone and all other

proteins.

2. The receptor must be able to transmit the information gained from

binding to the hormone into a cellular response.

Hormones may be secreted into blood and affect cells at distant sites. Some

hormones known to act and affect neighboring cells or even have effects on

the same cells that secreted the hormone. . Three actions are defined:

•

Endocrine action

: the hormone is distributed in blood and binds to distant

target cells.

•

Paracrine action

: the hormone acts locally by diffusing from its source to

target cells in the neighborhood.

•

Autocrine action

: the hormone acts on the same cell that produced it.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

9

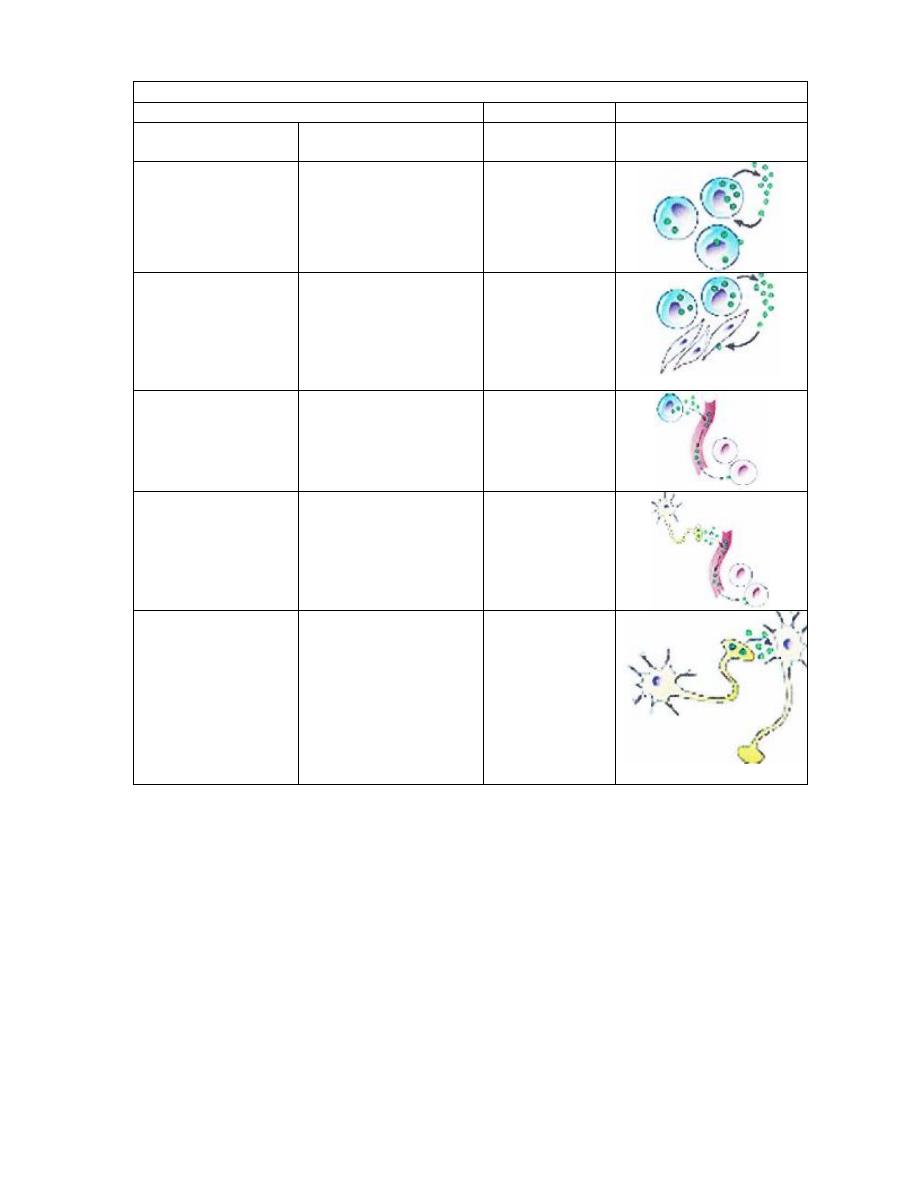

Types of hormones

Chemical messengers

Example

Description

Intracellular

chemical signal

Prostaglandins

Secreted by cells in a

local area and

influences the activity

of the same cell from

which it was secreted

Autocrine

Histamine,

Prostaglandins

Produced by a wide

variety of tissues and

secreted into tissue

spaces; has a

localized effect on

adjacent cells

Paracrine

Thyroxine,

Insulin

Secreted into the

blood by specialized

cells; travels by the

blood to target tissues

Hormone

Oxytocin,

Antidiuretic

hormone

Produced by neurons

and functions like

hormones

Neurohormone

Acetylcholine,

norepinephrine

Produced by neurones

and secreted into

extracellular spaces

by nerve terminals;

travels short

distances, influences

postsynaptic cells or

effector cells.

Neurotransmitter

Two important terms are used to refer to molecules that bind to the

hormone-binding sites of receptors:

•

Agonists

are molecules that bind the receptor and induce all the post-

receptor events that lead to a biologic effect. In other words, they act

like the "normal" hormone, although perhaps more or less potently.

Antagonists

are molecules that bind the receptor and block binding of

the agonist, but fail to trigger intracellular signaling events. Hormone

antagonists are widely used as drugs.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

10

Mechanism of Action of Hormone:

Understanding mechanism of action is not only of great interest to basic

science, but critical to understanding and treating diseases of the endocrine

system, and in using hormones as drugs.

There are two fundamental mechanisms by which a hormone can change its

target cell. These mechanisms are:

•

Activation of enzymes and other dynamic molecules: Most

enzymes fluctuate between conformational states that are catalytically

active versus inactive. Many hormones affect their target cells by

inducing such transitions, usually causing an activation of one of more

enzymes. Because enzymes are catalysts and often serve to activate

additional enzymes, a seemingly small change induced by hormone-

receptor binding can lead to widespread consequences within the cell.

•

Modulation of gene expression: Stimulating transcription of a group of

genes clearly can alter a cell's phenotype by leading to a burst of

synthesis of new proteins. Similarly, if transcription of a group of

previously active genes is shut off, the corresponding proteins will soon

disappear from the cell.

More specifically, when a receptor becomes bound to a hormone, it

undergoes a conformational change which allows it to interact

productively with other components of the cells, leading ultimately to an

alteration in the physiologic state of the cell.

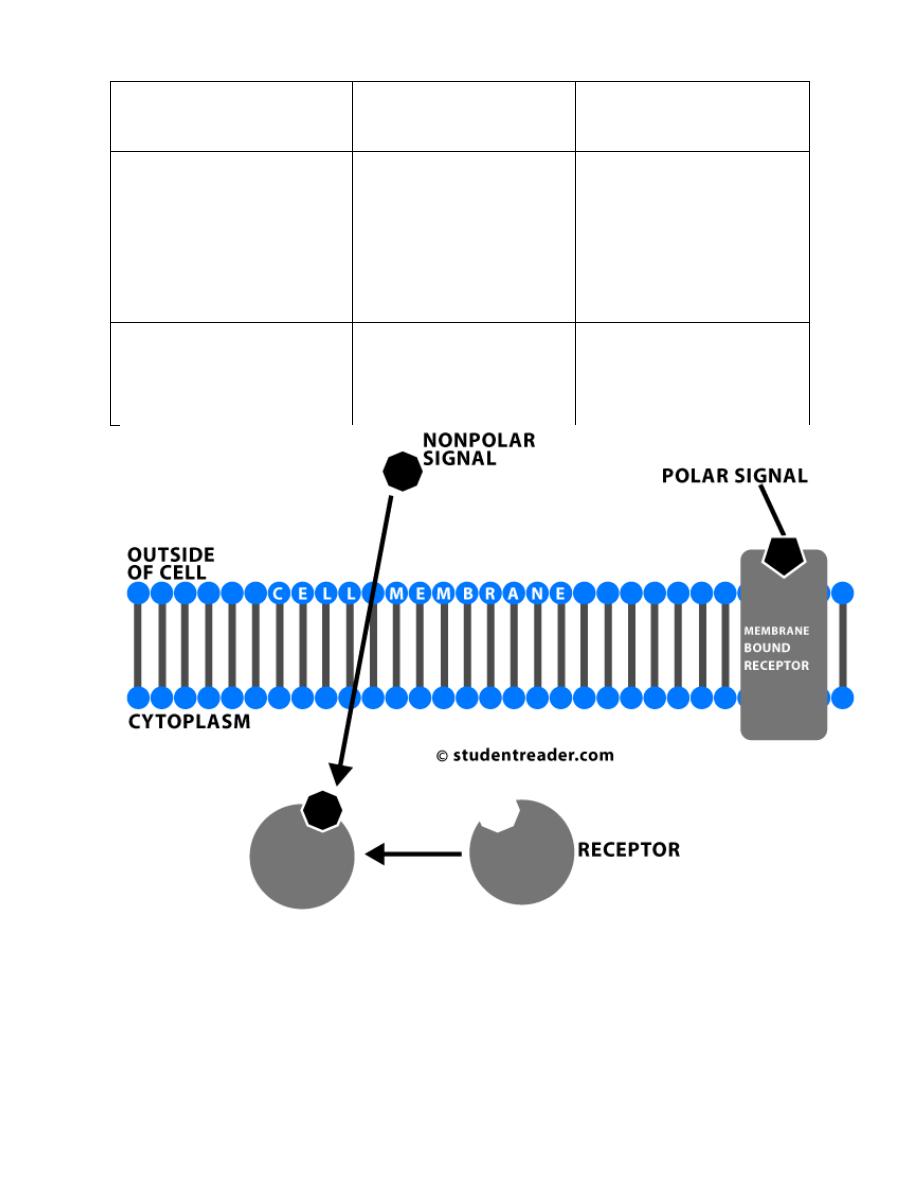

Despite the molecular diversity of hormones, all hormone receptors can be

categorized into one of two types, based on their location within the cell:

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

11

Location of Receptor

Classes of Hormones

Principle Mechanism

of Action

Cell surface receptors

(plasma membrane)

Proteins and peptides,

catecholamines and

eicosanoids

(water soluble)

Generation of second

messengers which alter

the activity of other

molecules - usually

enzymes - within the cell

Intracellular receptors

(cytoplasm and/or

nucleus)

Steroids and thyroid

hormones

(lipid soluble)

Alter transcriptional

activity of responsive

genes

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

12

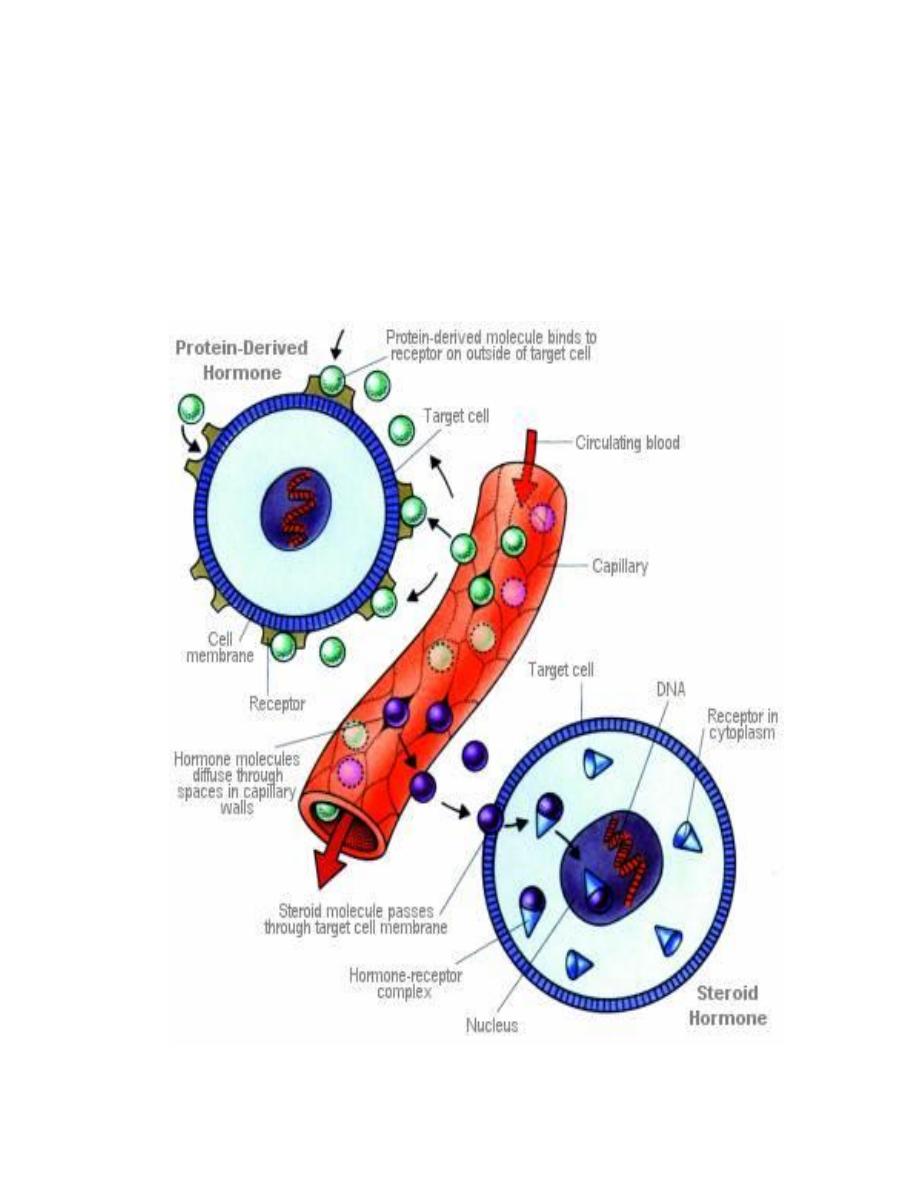

1. Hormones with Cell Surface Receptors

Protein and peptide hormones, catecholamines like epinephrine, and

eicosanoids such as prostaglandins find their receptors decorating the

plasma membrane of target cells. Binding of hormone to receptor initiates a

series of events which leads to generation of so-called second messengers

within the cell (the hormone is the first messenger). The second messengers

then trigger a series of molecular interactions that alter the physiologic state

of the cell. Another term used to describe this entire process is signal

transduction.

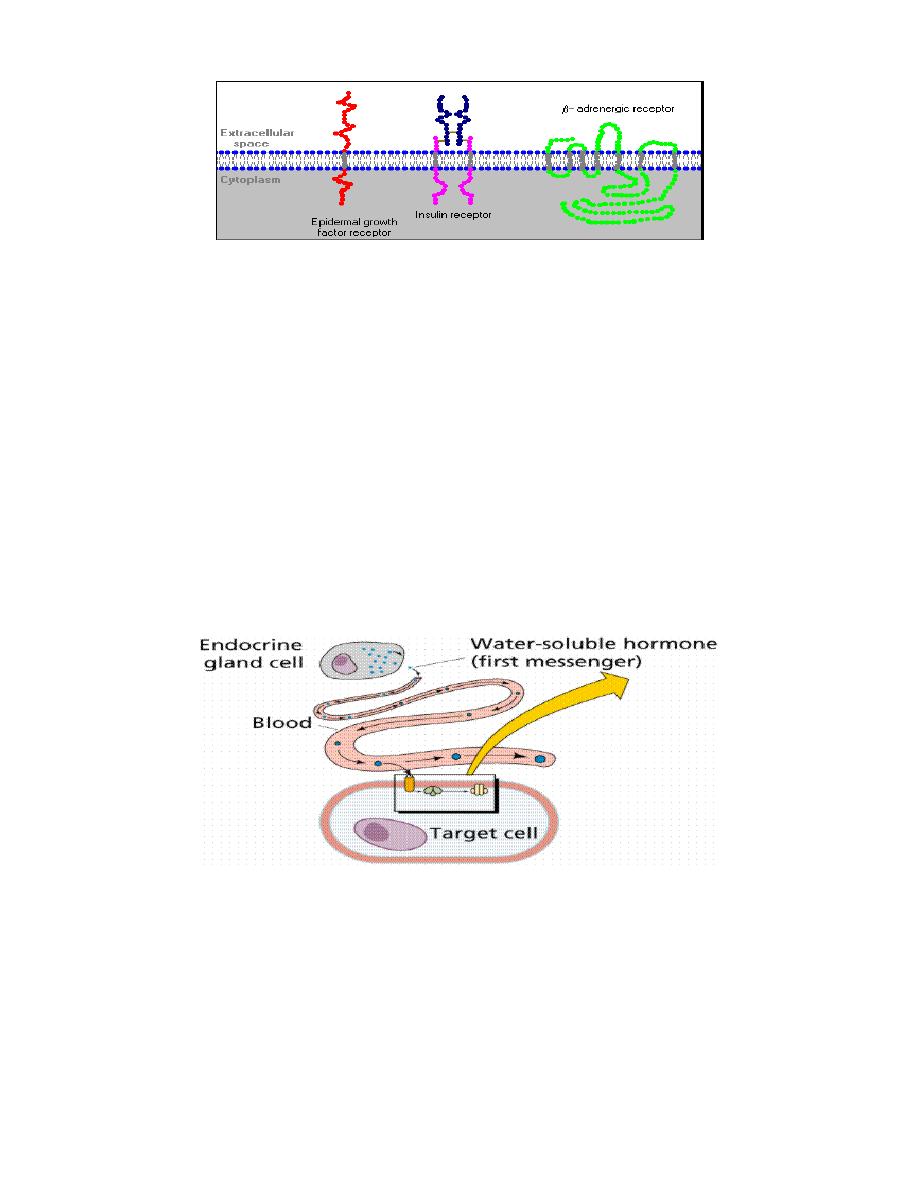

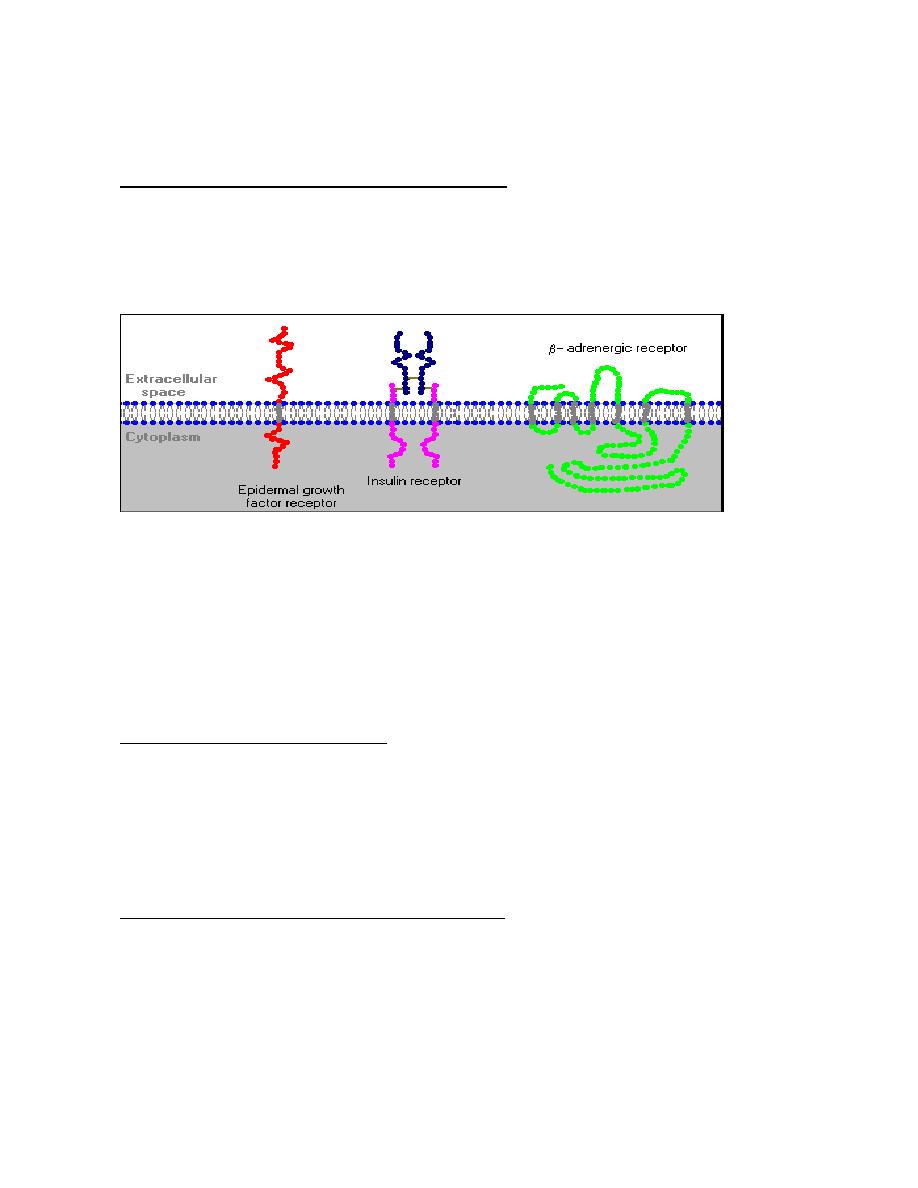

Structure of Cell Surface Receptors

Cell surface receptors are integral membrane proteins and, as such, have

regions that contribute to three basic domains:

•

Extracellular domains: Some of the residues exposed to the outside

of the cell interact with and bind the hormone - another term for these

regions is the ligand-binding domain.

•

Transmembrane domains: Hydrophobic stretches of amino acids are

"comfortable" in the lipid bilayer and serve to anchor the receptor in the

membrane.

•

Cytoplasmic or intracellular domains: Tails or loops of the receptor

that are within the cytoplasm react to hormone binding by interacting in

some way with other molecules, leading to generation of second

messengers.

As shown below, some receptors are simple, single-pass proteins; many

growth factor receptors take this form. Others, such as the receptor for

insulin, have more than one subunit. Another class, which includes the beta-

adrenergic receptor, is threaded through the membrane seven times.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

13

Interaction of the hormone-bound receptor with other membrane or

cytoplasmic proteins is the key to generation of second messengers and

transduction of the hormonal signal.

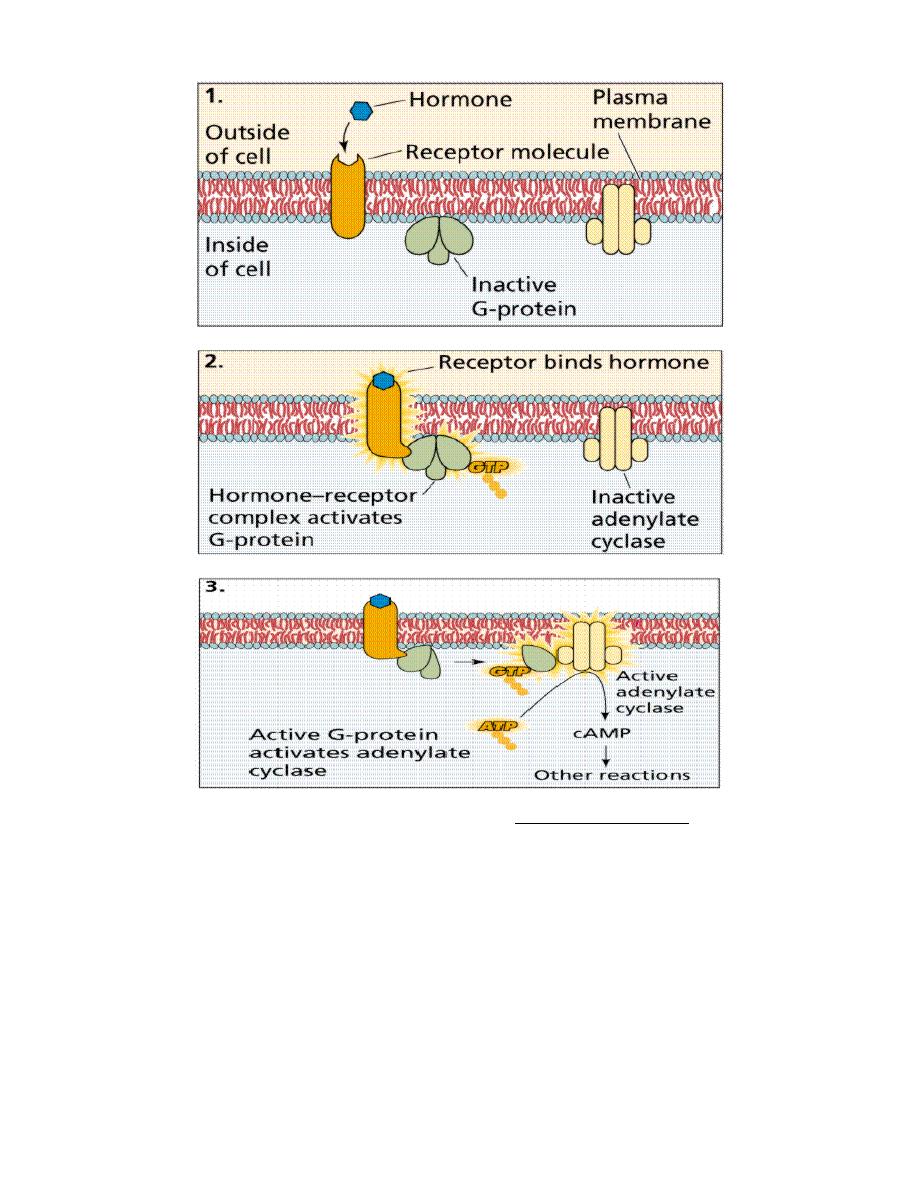

Second Messenger Systems

Nonsteroid hormones (water soluble) do not enter the cell but bind to plasma

membrane receptors, generating a chemical signal (second messenger)

inside the target cell. Second messengers activate other intracellular

chemicals to produce the target cell response.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

14

The action of nonsteroid hormones. Images from Purves et al., Life: The Science of Biology, 4th Edition, by

Sinauer Associates

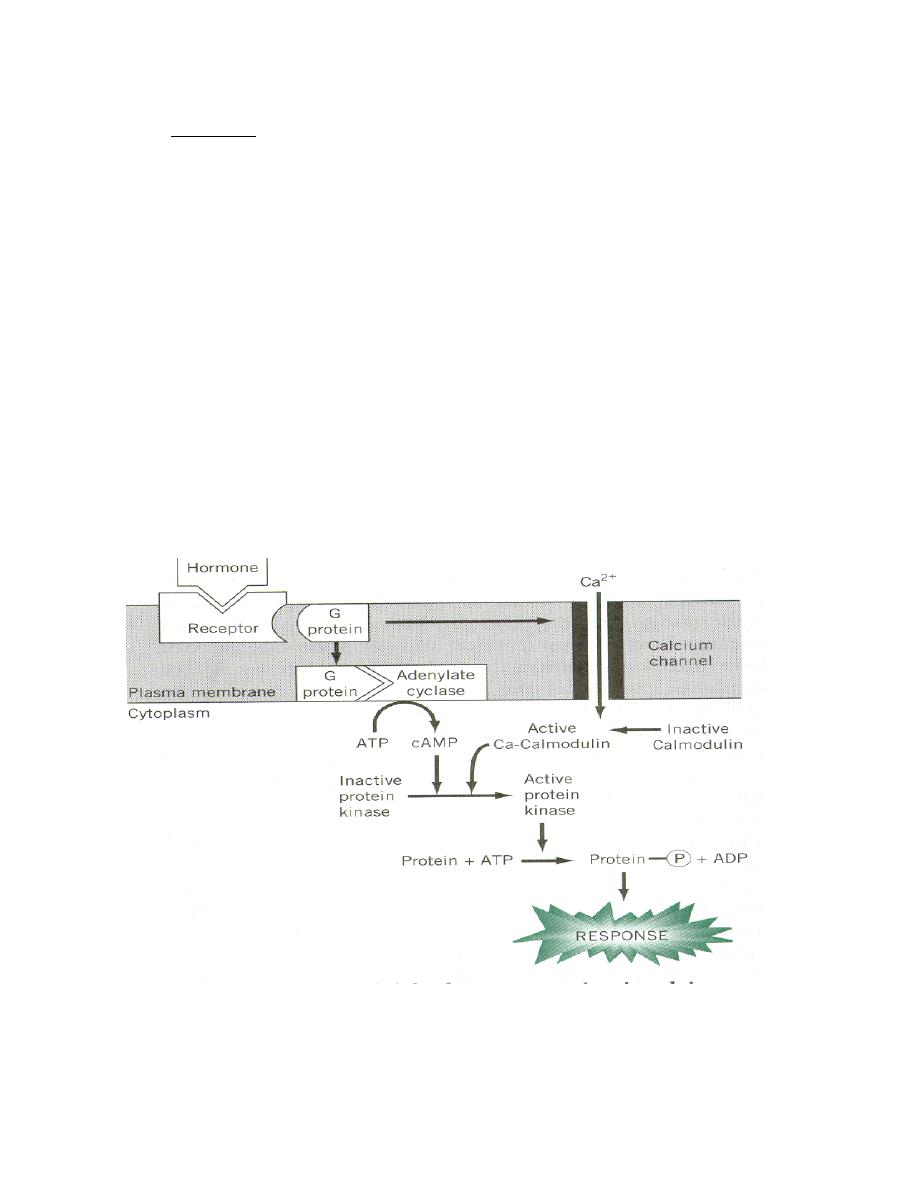

Currently, four second messenger systems are recognized in cells, as

summarized in the table below. Note that not only do multiple hormones

utilize the same second messenger system, but a single hormone can utilize

more than one system.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

15

Second Messenger

Examples of Hormones Which Utilize This

System

Cyclic AMP

Epinephrine and norepinephrine, glucagon,

luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating

hormone, thyroid-stimulating hormone,

calcitonin, parathyroid hormone, antidiuretic

hormone

Protein kinase activity

Insulin, growth hormone, prolactin, oxytocin,

erythropoietin, several growth factors

Calcium and/or

phosphoinositides

Epinephrine and norepinephrine, antidiuretic

hormone, gonadotropin-releasing hormone,

thyroid-releasing hormone.

Cyclic GMP

Atrial naturetic hormone, nitric oxide

In all cases, the seemingly small signal generated by hormone binding

its receptor is amplified within the cell into a cascade of actions that

changes the cell's physiologic state. Presented below are two examples of

second messenger systems commonly used by hormones.

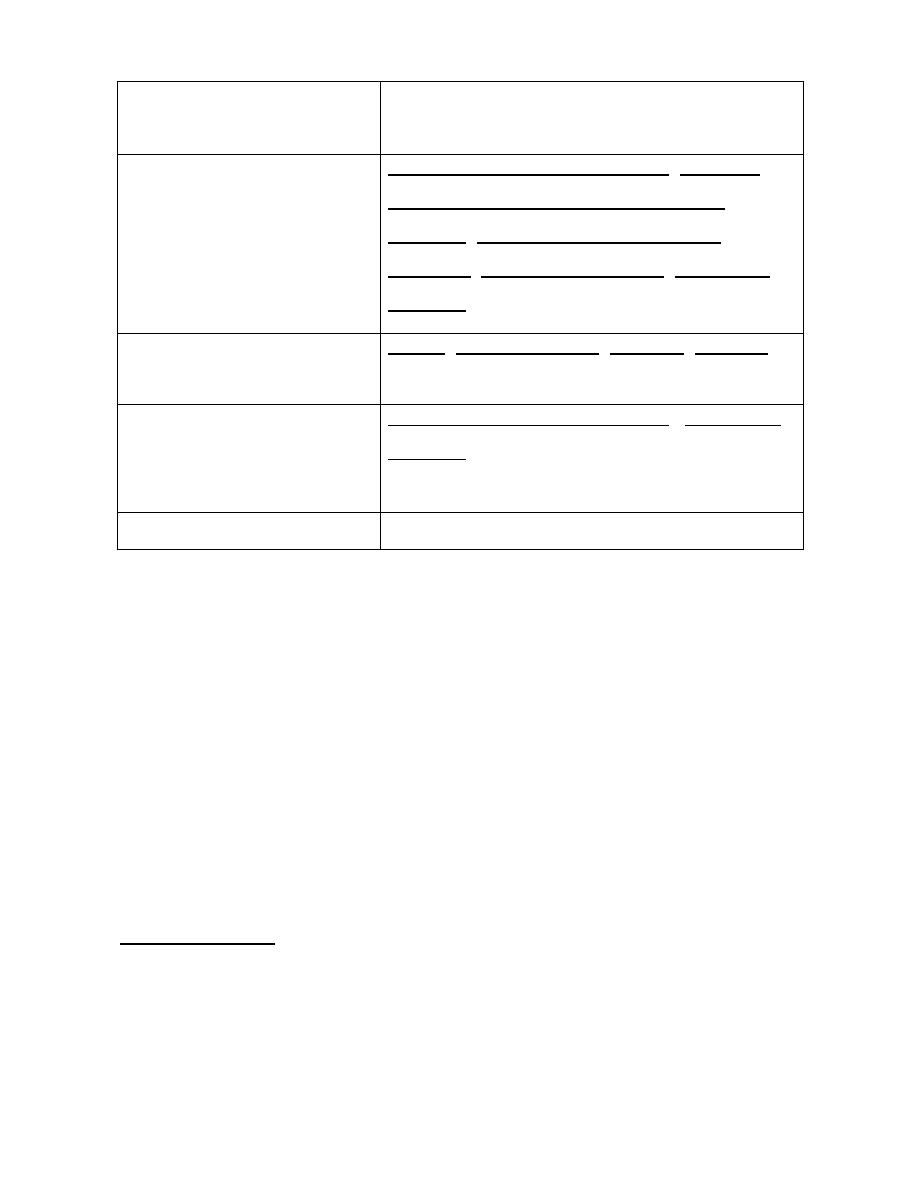

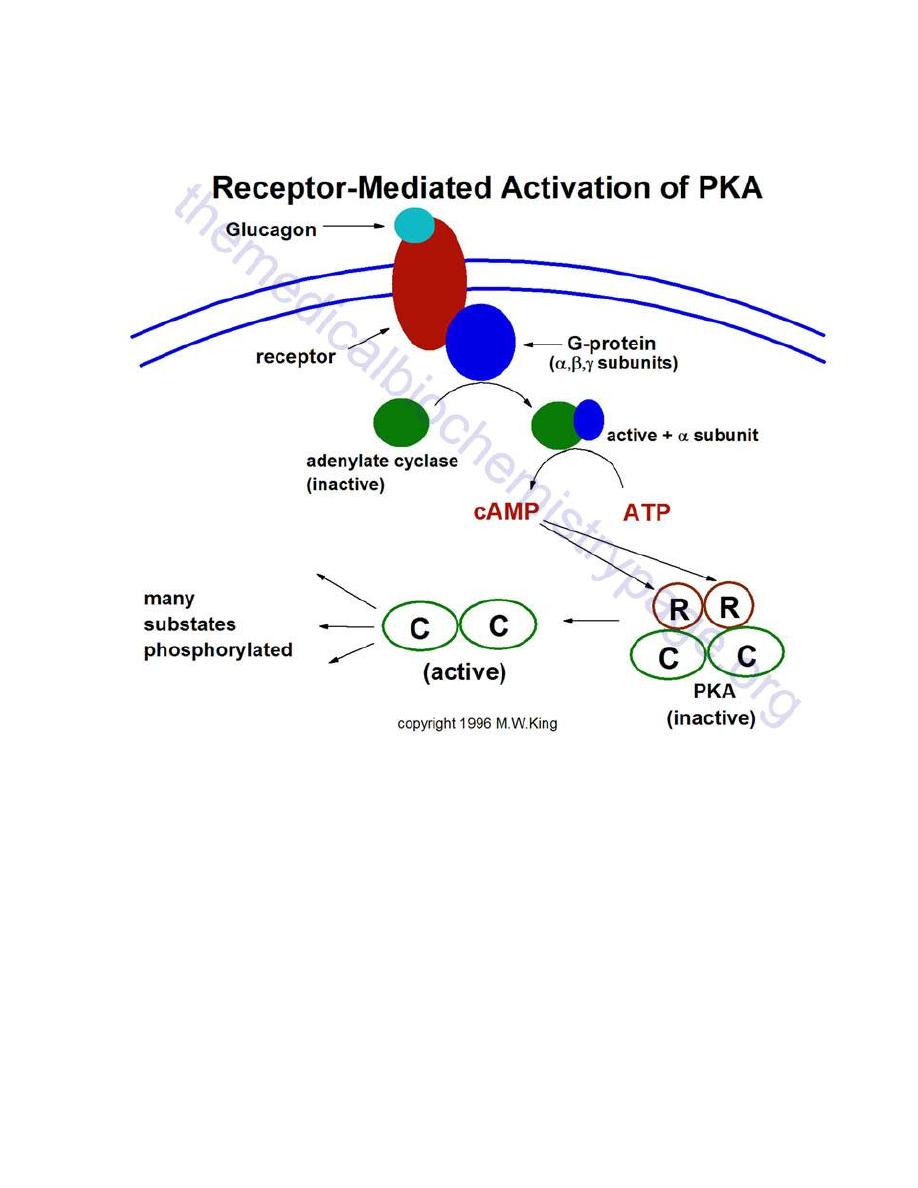

1. Cyclic AMP Second Messenger Systems

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is a nucleotide generated from

ATP through the action of the enzyme adenylate cyclase. The intracellular

concentration of cAMP is increased or decreased by a variety of hormones

and such fluctuations affect a variety of cellular processes. One prominent

and important effect of elevated concentrations of cAMP is activation of a

cAMP-dependent protein kinase called protein kinase A.

Protein kinase A is nominally in a catalytically-inactive state, but becomes

active when it binds cAMP. Upon activation, protein kinase A phosphorylates

a number of other proteins, many of which are themselves enzymes that are

either activated or suppressed by being phosphorylated. Such changes in

enzymatic activity within the cell clearly alter its state.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

16

Simple Example: mechanism of action of glucagon:

•

Glucagon binds its receptor in the plasma membrane of target cells

(e.g. hepatocytes).

•

Bound receptor interacts with and, through a set of G proteins, turns on

adenylate cyclase, which is also an integral membrane protein.

•

Activated adenylate cyclase begins to convert ATP to cyclic AMP,

resulting in an elevated intracellular concentration of cAMP.

•

High levels of cAMP in the cytosol make it probable that protein kinase

A will be bound by cAMP and therefore catalytically active.

•

Active protein kinase A "runs around the cell" adding phosphates to

other enzymes, thereby changing their conformation and modulating

their catalytic activity .

•

Levels of cAMP decrease due to destruction by cAMP-

phosphodiesterase and the inactivation of adenylate cyclase.

In the above example, the hormone's action was to modify the activity of pre-

existing components in the cell. Elevations in cAMP also have important

effects on transcription of certain genes.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

17

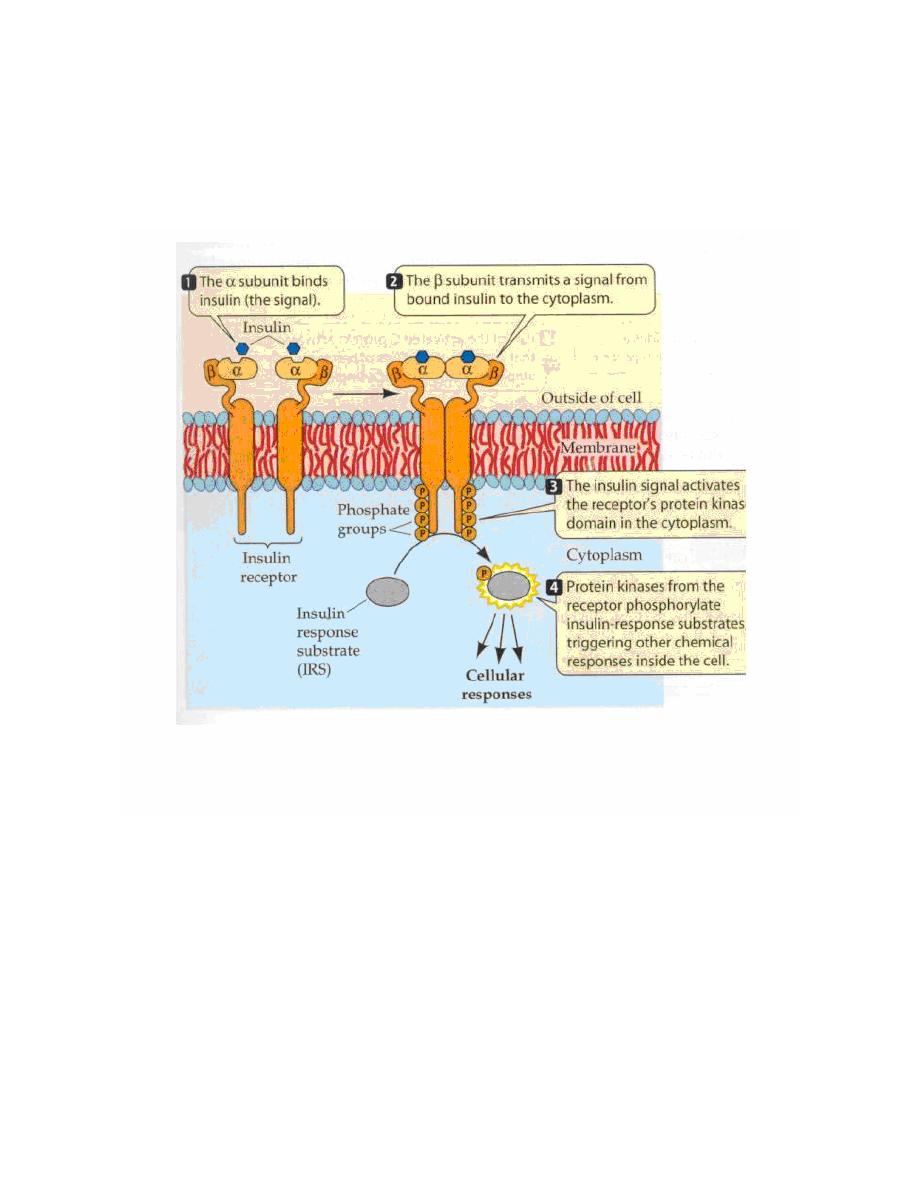

2. Tyrosine Kinase Second Messenger Systems

The receptors for several protein hormones are themselves protein

kinases which are switched on by binding of hormone. The kinase

activity associated with such receptors results in phosphorylation of tyrosine

residues on other proteins. Insulin is an example of a hormone whose

receptor is a tyrosine kinase.

The hormone binds to domains exposed on the cell's surface, resulting in a

conformational change that activates kinase domains located in the

cytoplasmic regions of the receptor. In many cases, the receptor

phosphorylates itself as part of the kinase activation process. The activated

receptor phosphorylates a variety of intracellular targets, many of which are

enzymes that become activated or are inactivated upon phosphorylation.

As seen with cAMP second messenger systems, activation of receptor

tyrosine kinases leads to rapid modulation in a number of target proteins

within the cell. Some of the targets of receptor kinases are protein

phosphatases which, upon activation by receptor tyrosine kinase, become

competent to remove phosphates from other proteins and alter their activity.

Again, a seemingly small change due to hormone binding is amplified into a

multitude of effects within the cell.

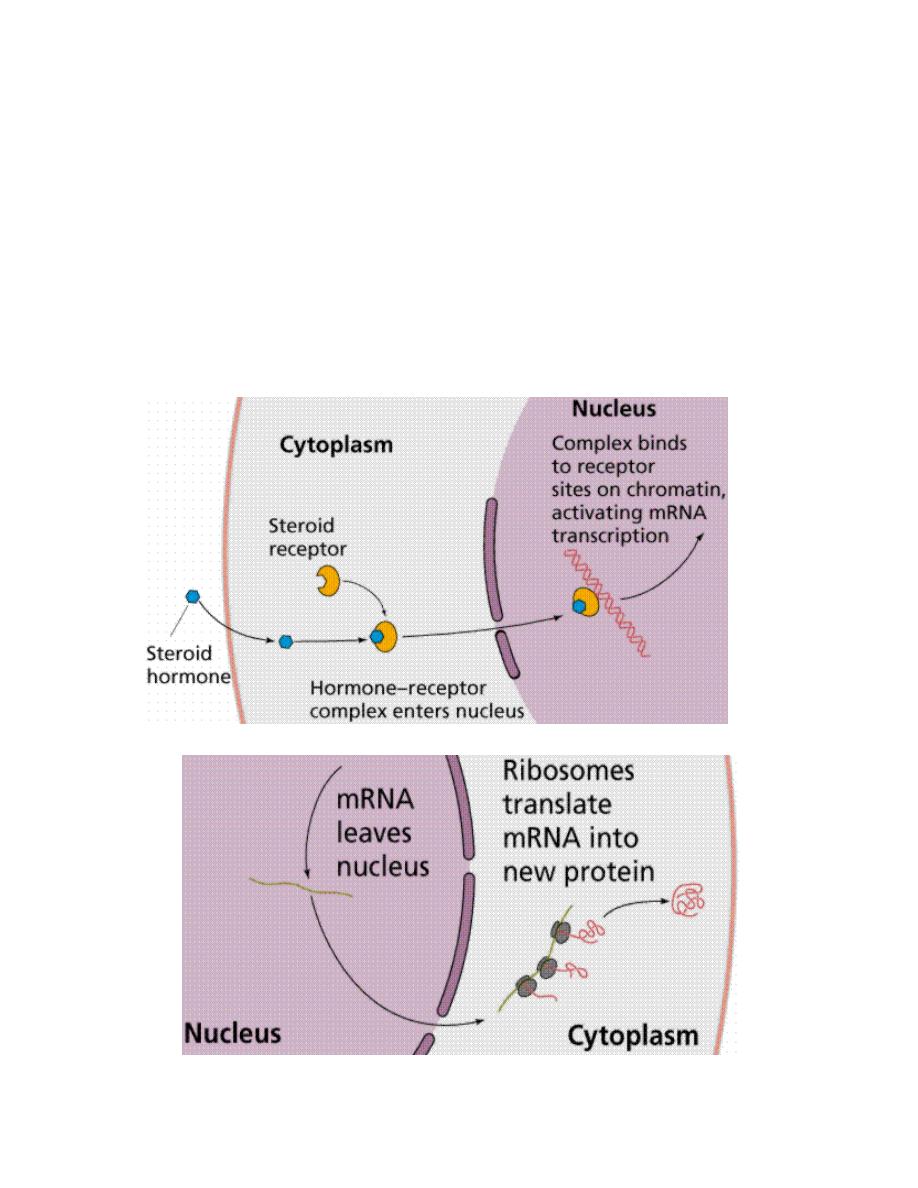

2.

Hormones with Intracellular Receptors

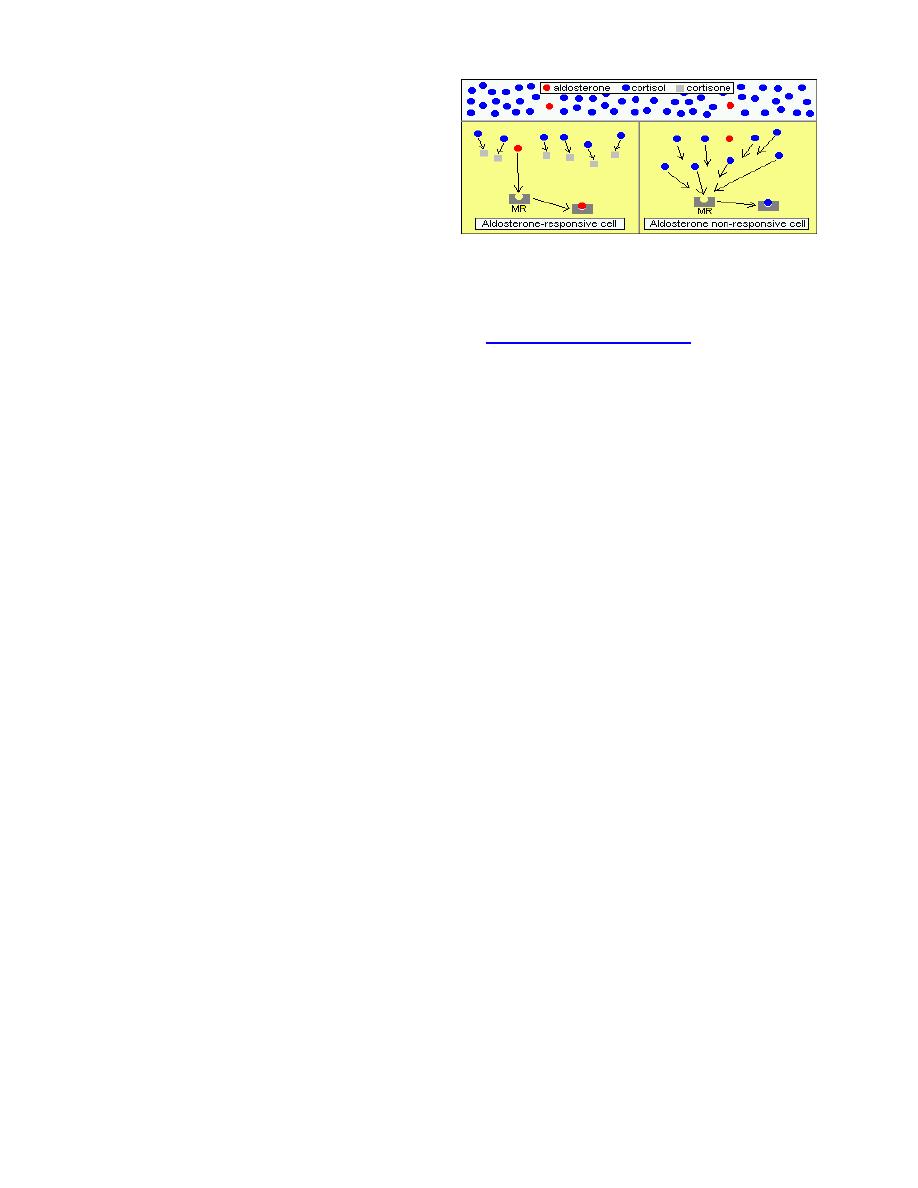

Receptors for steroid and thyroid hormones are located inside target cells, in

the cytoplasm or nucleus, and function as ligand-dependent transcription

factors. The hormone-receptor complex binds to promoter regions of

responsive genes and stimulate or sometimes inhibit transcription from those

genes. Thus, the mechanism of action of these hormones is to modulate

gene expression in target cells. By selectively affecting transcription from a

battery of genes, the concentration of those respective proteins are altered,

which clearly can change the phenotype of the cell.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

18

Structure of Intracellular Receptors

Steroid and thyroid hormone receptors are members of a large group of

transcription factors. All of these receptors are composed of a single

polypeptide chain that has, three distinct domains:

•

The amino-terminus

: In most cases, this region is involved in

activating or stimulating transcription by interacting with other

components of the transcriptional machinery. The sequence is highly

variable among different receptors.

•

DNA binding domain

: Amino acids in this region are responsible for

binding of the receptor to specific sequences of DNA.

•

The carboxy-terminus or ligand-binding domain

: This is the region

that binds hormone.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

19

In addition to these three core domains, two other important regions of the

receptor protein are a nuclear localization sequence, which targets the protein

to nucleus, and a dimerization domain, which is responsible for latching two

receptors together in a form capable of binding DNA.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

20

Hormone-Receptor Binding and Interactions with DNA

Being lipids, steroid hormones enter the cell by simple diffusion across the

plasma membrane. Thyroid hormones enter the cell by facilitated diffusion.

The receptors exist either in the cytoplasm or nucleus, which is where they

meet the hormone. When hormone binds to receptor, a characteristic

series of events occurs:

•

Receptor activation

is the term used to describe conformational

changes in the receptor induced by binding hormone. The major

consequence of activation is that the receptor becomes competent to

bind DNA.

•

Activated receptors bind to hormone response elements

, which are

short specific sequences of DNA which are located in promoters of

hormone-responsive genes.

•

Transcription from those genes to which the receptor is bound is

affected.

Most commonly, receptor binding stimulates transcription.

The hormone-receptor complex thus functions as a transcription factor.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

21

Steroid Hormones

The second mechanism involves steroid hormones, which pass through the

plasma membrane and act in a two step process. Steroid hormones bind,

once inside the cell, to the nuclear membrane receptors, producing an

activated hormone-receptor complex. The activated hormone-receptor

complex binds to DNA and activates specific genes,

increasing production of

proteins.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

22

Control of Endocrine Activity

The physiologic effects of hormones depend largely on their concentration in blood and

extracellular fluid.

The concentration of hormone as seen by target cells is determined by three factors:

1. Rate of production

:

Synthesis and secretion of hormones are the most highly

regulated aspect of endocrine control. Such control is mediated by positive and

negative feedback circuits.

2. Rate of delivery

:

An example of this effect is blood flow to a target organ or group

of target cells:

TRANSPORT OF HORMONES: hormones must be transported at least some distance to

their target organs. The primary transport medium is the plasma, although the lymphatic

system and the cerebrospinal fluid are also important. Since delivery of the hormone to its

target tissue is required before a hormone can exert its effects, the presence or absence of

specific transport mechanisms play a major role in mediating hormonal action.

A) The water-soluble hormones (peptide hormones, catecholamines) are transported

in plasma in solution and require no specific transport mechanism. Because of this,

the water-soluble hormones are generally short-lived. These properties allow for

rapid shifts in circulating hormone concentrations, which is necessary with the

pulsatile tropic hormones or the catecholamines. This is consistent with the

rapid onset of action of the water-soluble hormones.

B) The lipid-soluble hormones (thyroid hormone, steroids) circulate in the plasma

bound to specific carrier proteins. Many of the proteins have a high affinity for

specific hormone, such as thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG), sex hormone-

binding globulin (SHBG), and cortisol-binding globulin (CBG). Non-specific, low-

affinity] binding of these hormones to albumin also occurs. Carrier proteins

act as reservoirs of hormone. Since it is generally believed that only the free hor-

mone can enter cells, a dynamic equilibrium must exist between the bound and

free hormone. Thus, alterations in the amount of binding protein available, or in

the affinity of the hormone for the binding protein, can markedly alter the total

circulating pool of hormone without affecting the free concentration of hormone.

Carrier proteins act as buffers to both blunt sudden increases in hormone

concentration and to diminish degradation of the hormone once it is secreted. Thus, the

half-life of hormones that utilize carrier proteins is longer than those that are not protein-

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

23

bound. Indeed, carrier proteins have a profound effect on the clearance rate of hormones;

the greater the capacity for high affinity binding of the hormone in the plasma, the slower

the clearance rate. Also, the carrier proteins allow slow, tonic delivery of the hormone to

its target tissue. This is consistent with the slower onset of action of the lipid-soluble

hormones.

3. Rate of degradation and elimination

:

Hormones, like all biomolecules, have

characteristic rates of decay, and are metabolized and excreted from the body

through several routes.

HORMONE METABOLISM: Clearance of hormones from the circulation plays a critical role

in the modulation of hormone levels in response to varied physiologic and pathologic

processes. The time required to reach a new steady-state concentration in response to

changes in hormone release is dependent upon the half-life of the hormone in the serum.

Thus, an increase in hormone release or administration will have a much more marked effect

if the hormone is cleared rapidly from the circulation as opposed to one that is cleared more

slowly.

Most peptide hormones have a plasma half-life measured in minutes, consistent with the

rapid actions and pulsatile nature of the secretion of these hormones. This rapid clearance

is achieved by the lack of protein binding in the plasma, degradation or internalization of the

hormone at its site of action, and ready clearance of the hormone by the kidney. Binding to

serum proteins markedly decreases hormone clearance, as is observed with the steroid

hormones and the iodothyronines. Metabolism of the steroid hormones occurs primarily in

the liver by reductions, conjugations, oxidations, and hydroxylations, which serve to

inactivate the hormone and increase their water-solubility, facilitating their excretion in the

urine and the bile. Metabolic transformation also may serve to activate an inactive hormone

precursor, such as the deiodination of thyroxine to form T

3

. Hormone metabolism is not as

tightly regulated as is hormone synthesis and release. However, alterations in the metabolic

pathways may be clinically important.

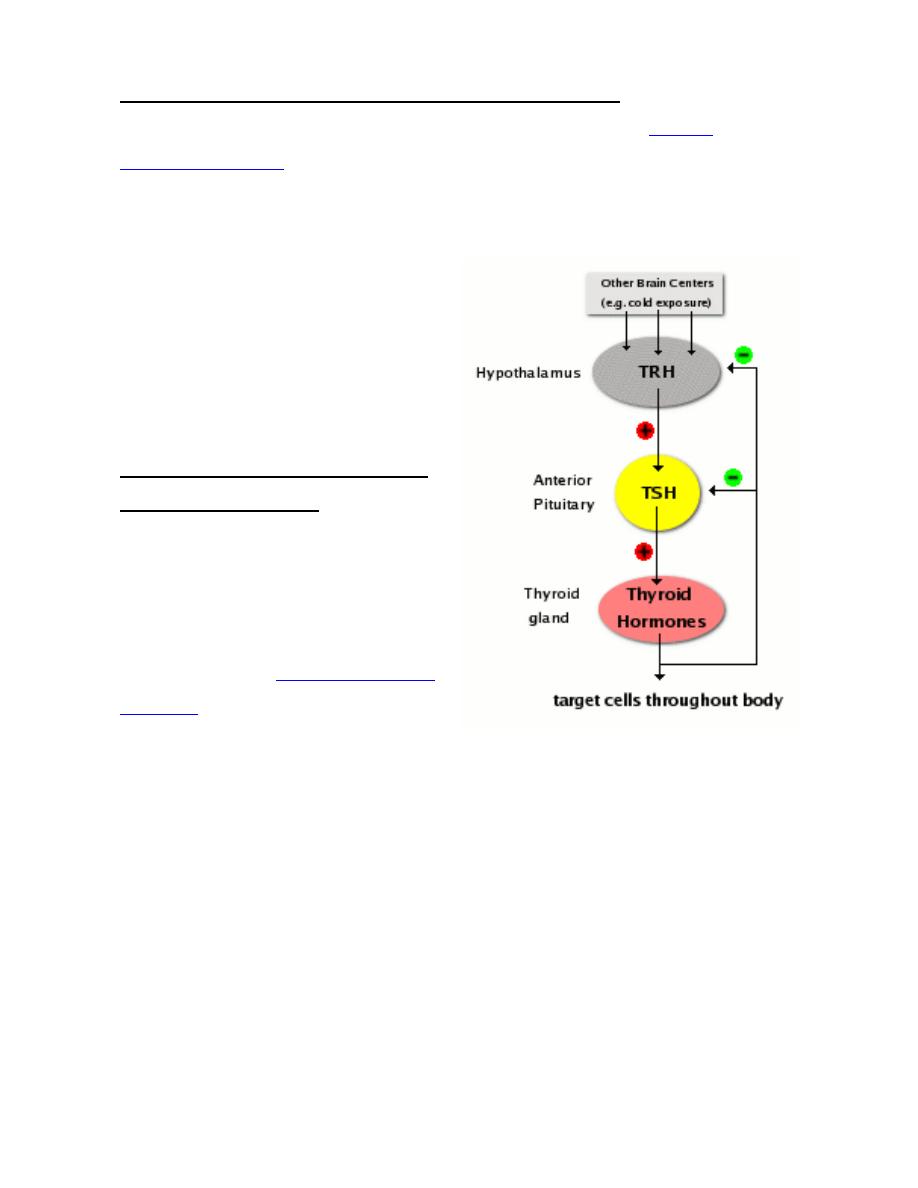

Feedback Control of Hormone Production

Feedback circuits are at the root of most control mechanisms in physiology, and are

particularly prominent(obvious) in the endocrine system. Instances of positive feedback

certainly occur, but negative feedback is much more common.

Feedback loops are used extensively to regulate secretion of hormones in the

hypothalamic-pituitary axis. An important example of a negative feedback loop is seen in

control of thyroid hormone secretion. The thyroid hormones thyroxine and triiodothyronine

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

24

("T4 and T3") are synthesized and secreted by thyroid glands and affect metabolism

throughout the body. The basic mechanisms for control in this system are:

•

Neurons in the hypothalamus secrete thyroid releasing hormone (TRH), which

stimulates cells in the anterior pituitary to secrete thyroid-stimulating hormone

(TSH).

•

TSH binds to receptors on epithelial cells in the thyroid gland, stimulating synthesis

and secretion of thyroid hormones, which affect probably all cells in the body.

•

When blood concentrations of thyroid hormones increase above a certain threshold,

TRH-secreting neurons in the hypothalamus are inhibited and stop secreting TRH.

This is an example of "negative feedback".

Inhibition of TRH secretion leads to shut-off of TSH secretion, which leads to shut-off of

thyroid hormone secretion. As thyroid hormone levels decay below the threshold, negative

feedback is relieved, TRH secretion starts again, leading to TSH secretion...

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

25

Biochemistry and

Disorders of

Hormones of the

Hypothalamic and

pituitary gland

(hypothalamus

and pituitary axis)

1. Hormones of the hypothalamus

Prof. Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

26

Hypothalamic and Pituitary Hormones

Lecture 3

Thursday 23/2

1. Hormones of the hypothalamus

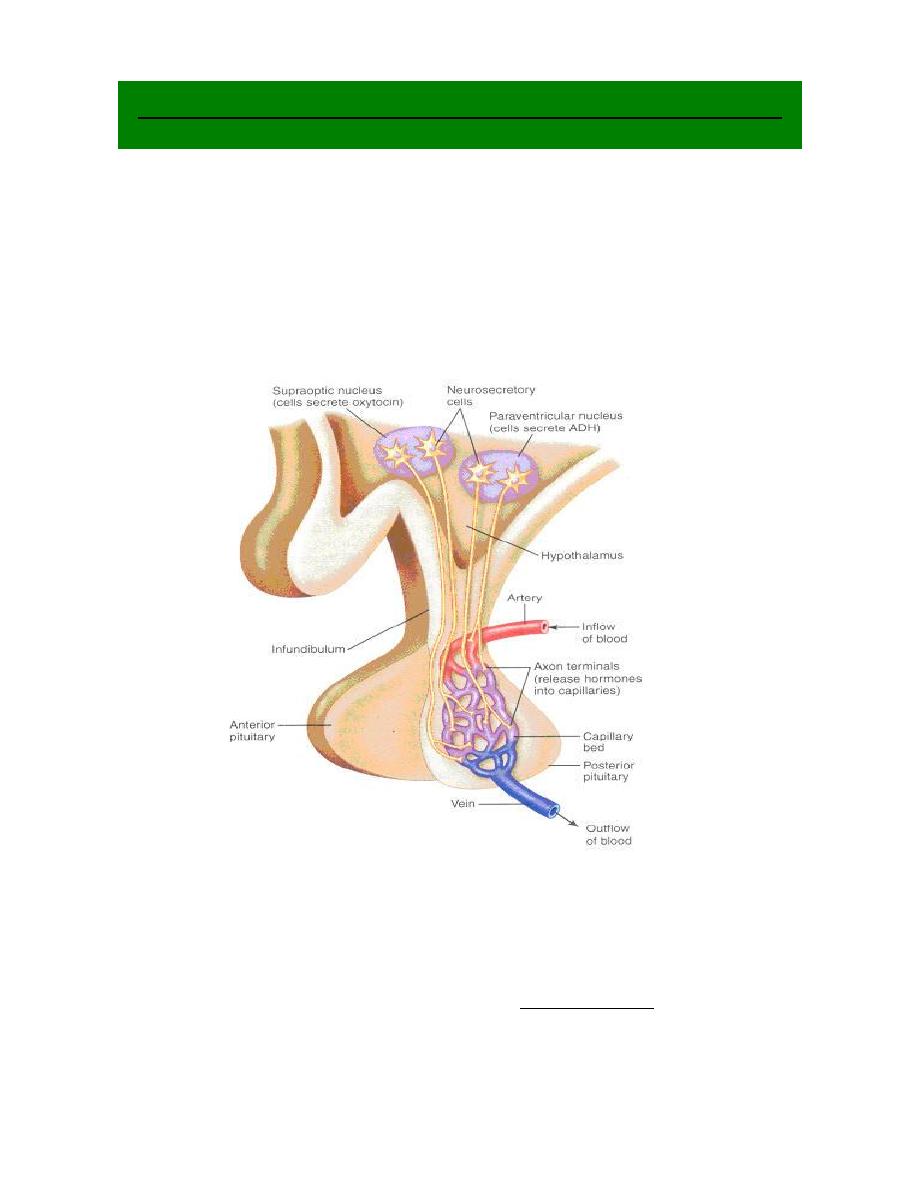

The hypothalamus is an integral part of the substance of the brain. A small cone-shaped

structure, it projects downward, ending in the pituitary stalk, a tubular connection to the

pituitary gland, which is a double lobed structure that produces the endocrine secretions

when stimulated by the hypothalamus.

Regulation of hormone secretion

The hypothalamus regulates homeostasis

.

It links the {nervous_system} to the {endocrine

system}. In addition to secreting neurotransmitters and neuromodulators, the

hypothalamus synthesizes and secretes a number of neurohormones. The neurons

secreting neurohormones are true endocrine cells.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

27

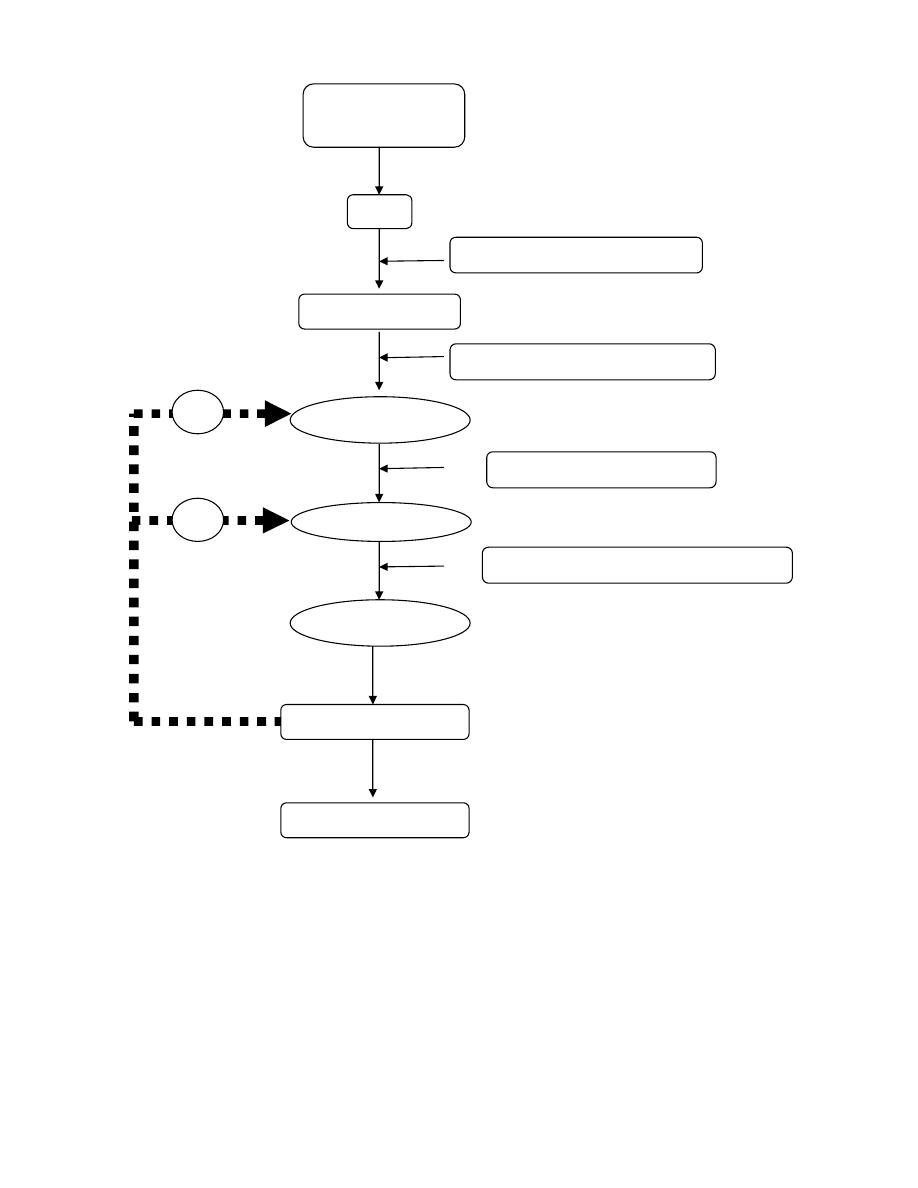

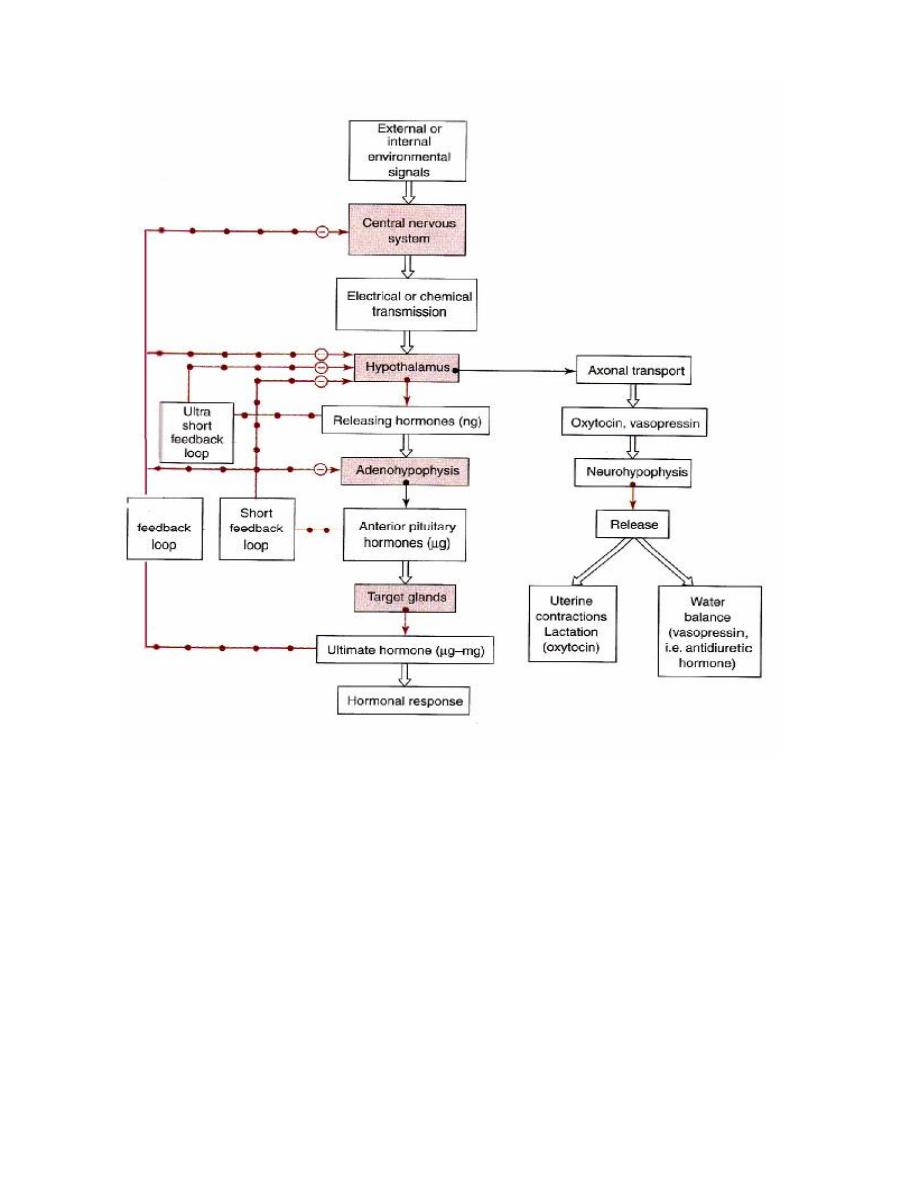

Hormonal cascade of signals from CNS to ultimate hormone.

The target "gland" is the last hormone-producing tissue in the cascade, which is stimulated

by an appropriate anterior pituitary hormone. Examples are thyroid gland, adrenal cortex,

ovary and testes. Ultimate hormone feedback negatively on sites producing intermediate

hormones in the cascade. Amounts (nanogram (ng), microgram (µg), and milligram (mg)

represent approximate quantities of hormone released.

Environmental or

internal signal

CNS

Limbic system

Electrical –chemical signal

Hypothalamus

Electrical –chemical signal

Anterior

Target "gland"

Releasing hormones (ng)

Anterior pituitary tropic hormone (µg)

Ultimate Hormone (mg)

Systemic effects

N

e

g

a

ti

v

e

f

e

e

d

b

a

c

k

i

n

h

ib

it

io

n

-

ve

-

ve

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

28

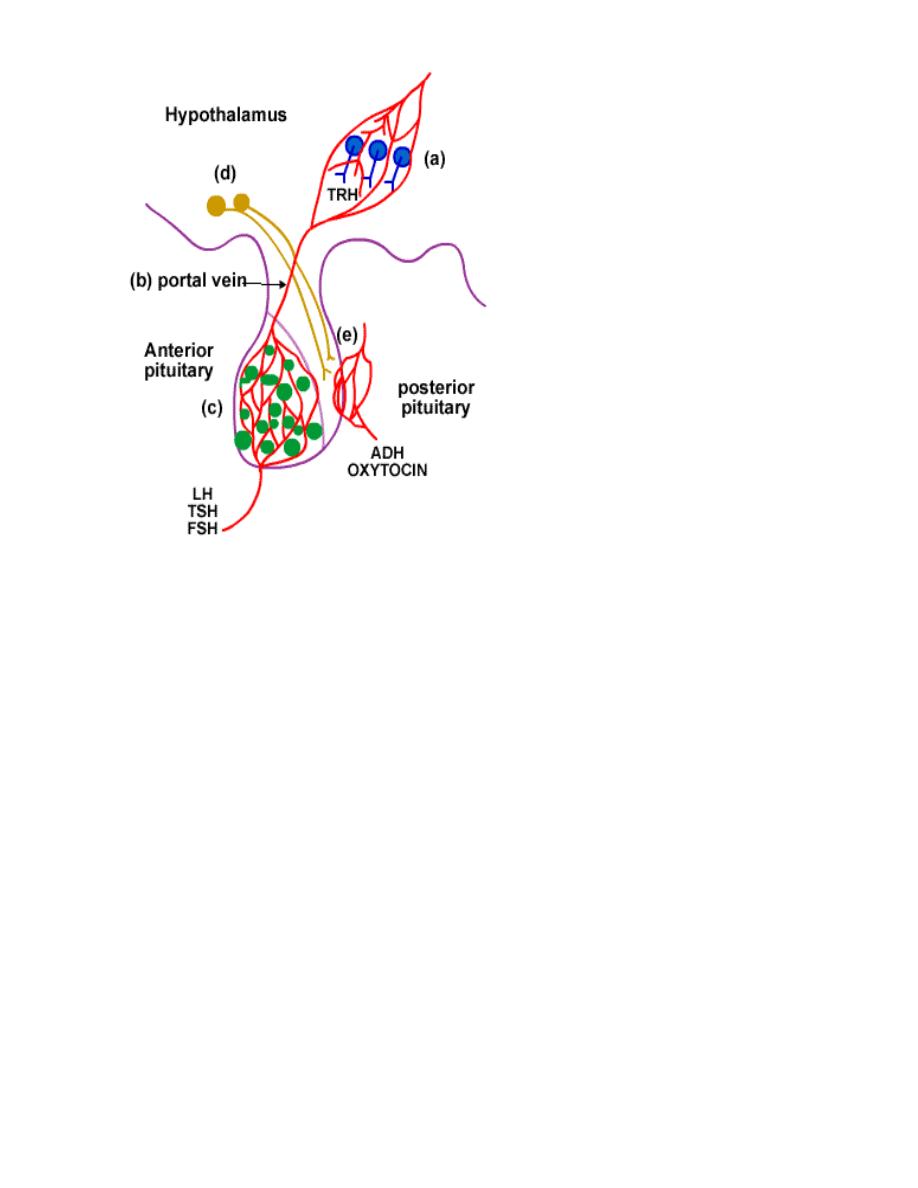

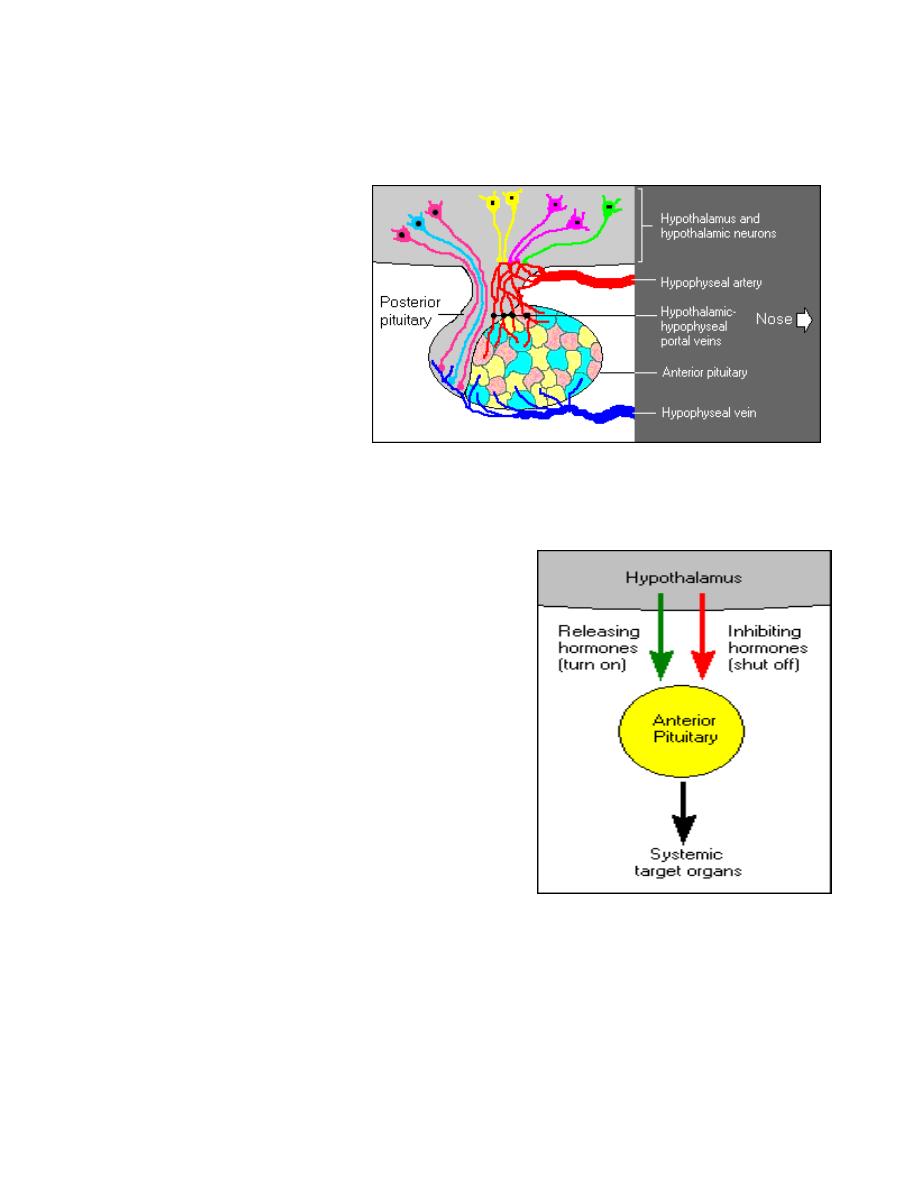

The hypothalamus controls each lobe

of the pituitary slightly differently.

1. control of Anterior lobe

a. The hypothalamus acts

as an endocrine gland.

b. Hormones are sent

from the hypothalamus

to the anterior pituitary

via a blood vessel

called the portal vein.

c. The target tissue is the

anterior lobe of the

pituitary e.g. LH, TSH,

and FSH.

2. control of the Posterior lobe

d. Neuro-hormones are synthesized in the hypothalamus neurons. They are

transported and stored in vesicles in the axon ending located in the posterior

pituitary.

e. Nerve impulses travel down the axon into the posterior pituitary. This causes

the release of the vesicles of hormones into the blood stream at the

posterior pituitary e.g. oxytocin , and ADH.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

29

Many hormonal systems involve hypothalamus.

Cascade of hormonal responses starting with an external or internal signal. This signal is

transmitted first to the CNS and may involve the limbic system, including the hippocampus

and amygdala. These components innervate the hypothalamus in a specific region, which

responds by secreting (nanogram amounts) a specific releasing hormone. Releasing

hormones are transported down a closed portal system to the anterior pituitary, where they

cause secretion of microgram amounts of specific anterior pituitary hormones. These

access the general circulation through fenestrated local capillaries and trigger release of

an ultimate hormone in microgram to milligram daily amounts, which generates its

response by binding to receptors in target tissues. Overall, this system is an amplifying

cascade. Consequently, the organism is in intimate association with the external

environment. Solid arrows indicate a secretory process. Long arrows studded with open or

closed circles indicate negative feedback pathways (ultra-short, short, and long feedback

loops).

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

30

1) Thyrotropin-releasing hormone(TRH)

Is the simplest of the hypothalamic neuropeptides. It consists essentially of three amino

acids. Its basic sequence is glutamic acid-histidine-proline, although both ends of the

peptide are modified. The simplicity of this structure is deceiving for TRH is involved in an

extraordinary array of functions. Some of which are:

a. It stimulates the secretion of thyroid-stimulating hormone from the pituitary.

b. It also affects the secretion of prolactin from the pituitary.

The TRH-secreting cells are subject to stimulatory and inhibitory influences from higher

centers in the brain and they also are inhibited by circulating thyroid hormone.

2) Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)

Also known as luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH), is a peptide chain of 10

amino acids. It stimulates the synthesis and release of the two pituitary gonadotropins,

luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

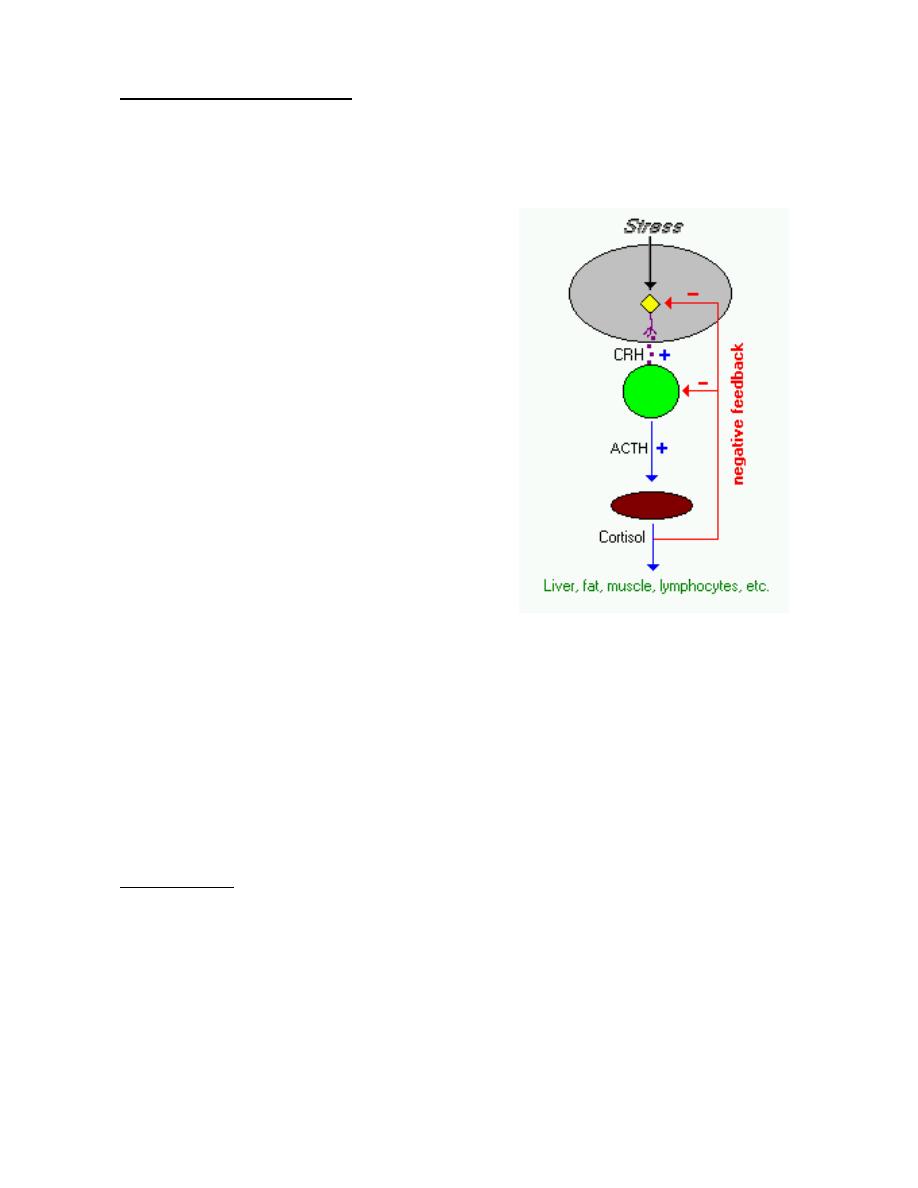

3) Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH)

Is a large peptide consisting of a single chain of 41 amino acids. It stimulates not only

secretion of corticotropin in the pituitary gland but also the synthesis of corticotropin in the

corticotropin-producing cells (corticotrophs) of the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. Many

factors, both neurogenic and hormonal, regulate the secretion of CRH. Among the

hormones that play an important role in modulating the influence of CRH is cortisol, the

major hormone secreted by the adrenal cortex, which, as part of the negative feedback

mechanism. Vasopressin, the major regulator of the body's excretion of water, has an

additional ancillary role in stimulating the secretion of CRH.

Excessive secretion of CRH leads to an increase in the size and number of corticotrophs

in the pituitary gland, often resulting in a pituitary tumor. This, in turn, leads to excessive

stimulation of the adrenal cortex, resulting in high circulating levels of adrenocortical

hormones, the clinical manifestations of which are known as Cushing's syndrome.

Conversely, a deficiency of CRH-producing cells can, by a lack of stimulation of the

pituitary and adrenal cortical cells, result in adrenocortical deficiency.

4) Growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH or GRH)

Like CRH, growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) is a large peptide. A number of

forms have been described that differ from one another only in minor details and in the

number of amino acids (varying from 37 to 49). It is stimulated by stresses, including

physical exercise, and secretion is blocked by a powerful inhibitor called somatostatin.

Negative feedback control of GHRH secretion is mediated largely through compounds

called somatomedins, growth-promoting hormones that are generated when tissues are

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

31

exposed to growth hormone itself.

Isolated deficiency of GHRH (in which there is normal functioning of the hypothalamus

except for this deficiency) may be the cause of one form of dwarfism, a general term

applied to all individuals with abnormally small stature.

5) Prolactin release factor (PRF):

Appears to be released from the hypothalamus in a pulsatile fashion and it is the

fluctuation in PRF that regulates the circulating level of prolactin.

6) Somatostatin (Growth hormone release-inhibiting hormone; somatotropin

release-inhibiting hormone ( GHRIH or SRIH)

Somatostatin refers to a number of polypeptides consisting of chains of 14 to 28 amino

acids. Somatostatin is also a powerful inhibitor of pituitary TSH secretion. Somatostatin,

like TRH, is widely distributed in the central nervous system and in other tissues. It serves

an important paracrine function in the islets of Langerhans, by blocking the secretion of

both insulin and glucagon from adjacent cells. Somatostatin has emerged not only as a

powerful blocker of the secretion of GH, insulin, glucagon, and other hormones but also as

a potent inhibitor of many functions of the gastrointestinal tract, including the secretion of

stomach acid, the secretion of pancreatic enzymes, and the process of intestinal

absorption.

7) Prolactin release-inhibiting hormones (Dopamine and GAP)

GAP= GnRH-associated peptide

The hypothalamic regulation of prolactin secretion from the pituitary is different from the

hypothalamic regulation of other pituitary hormones in two respects:

1. First, the hypothalamus primarily inhibits rather than stimulates the release of

prolactin from the pituitary.

2. Second, this major inhibiting factor is not a neuropeptide, but rather the

neurotransmitter dopamine. Prolactin deficiency is known to occur, but only rarely.

Excessive prolactin production (hyperprolactinemia) is a common endocrine

abnormality.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

32

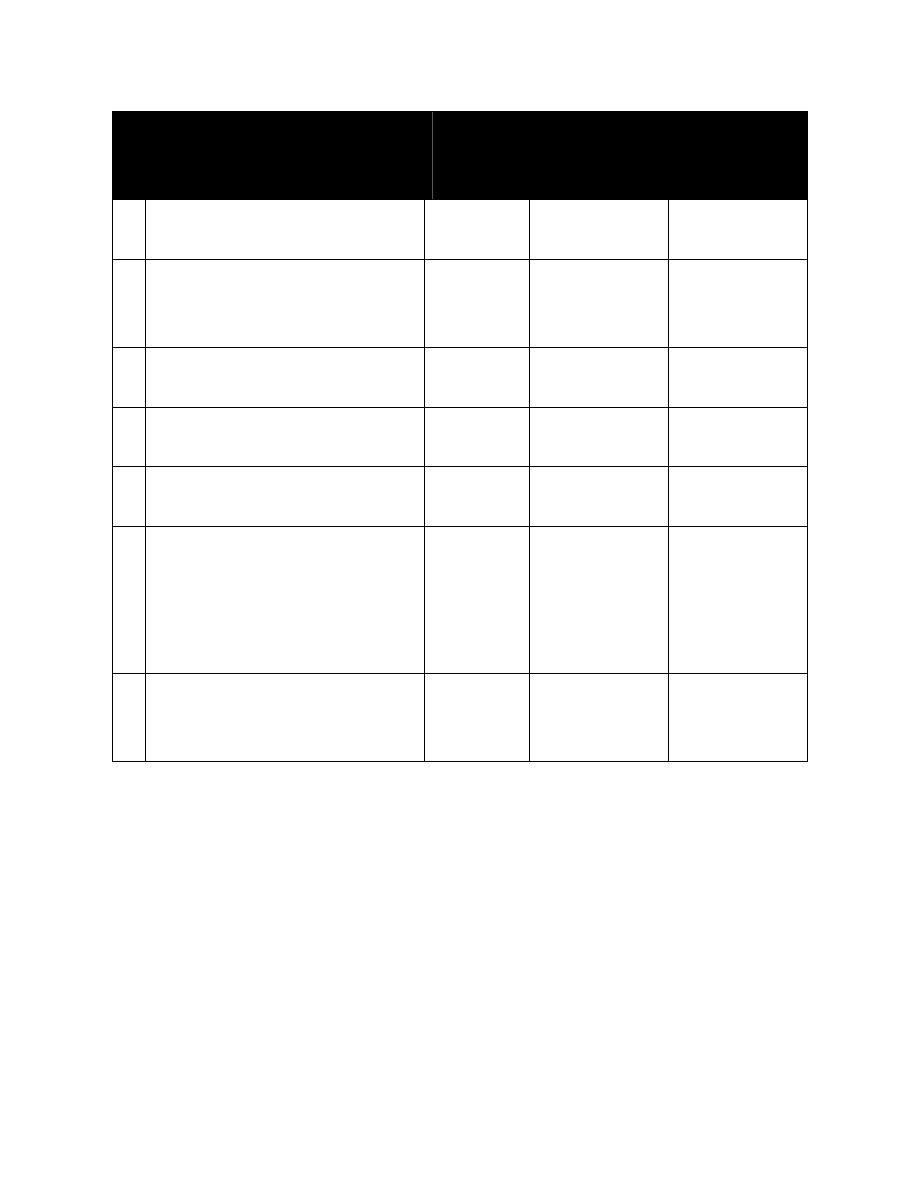

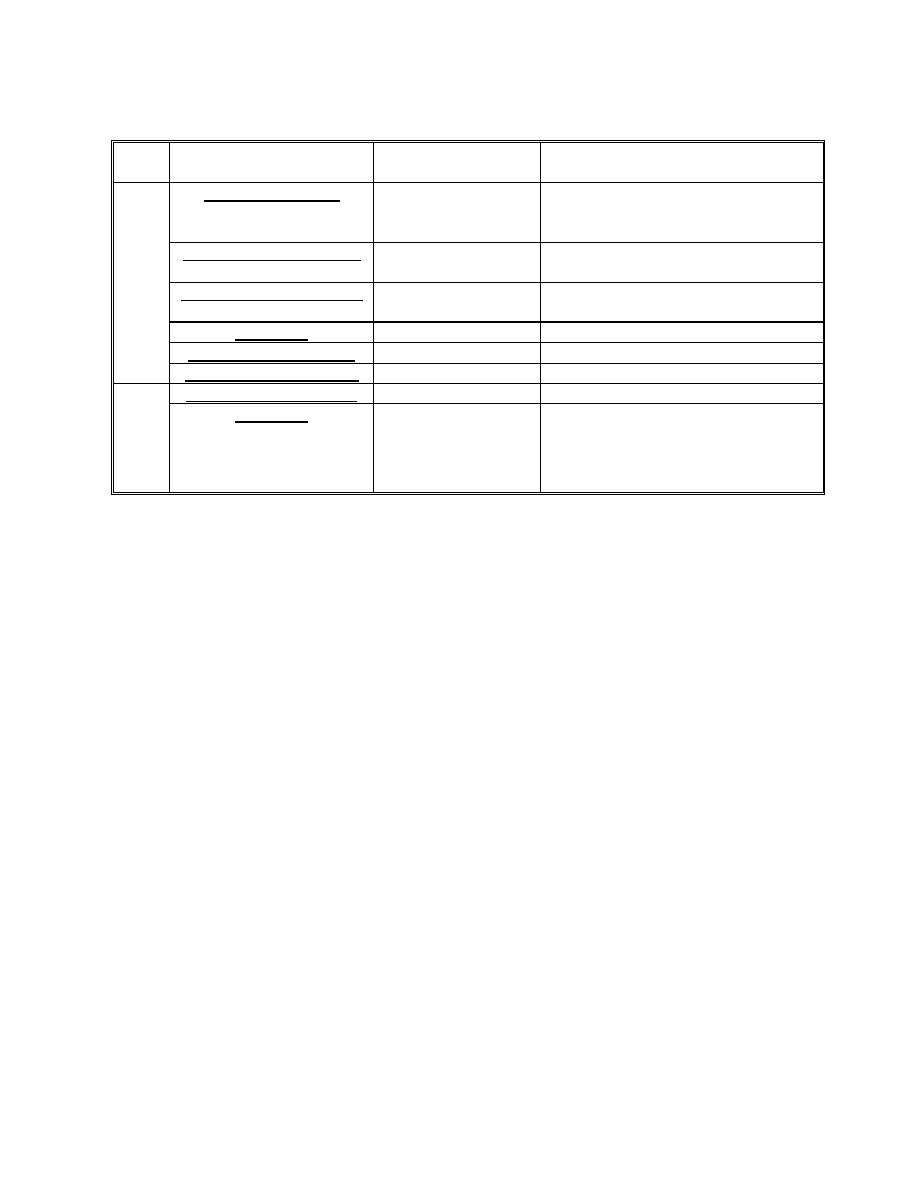

Table: Hypothalamic hypophysial-target gland hormones form integrated feedback loops

Hypothalamic hormones

No. of A.A

in

structure

Pituitary

Hormone

Affected

1

Target Gland

Hormone

Affected

1

Thyrotropin-releasing hormone

(TRH)

3

TSH (PRL)

T

3

, T

4

2

Gonadotropin-releasing

hormone (GnRH)

10

LH, FSH

Androgens,

estrogens,

progestins

3

Corticotropin-releasing

hormone (CRH)

41

ACTH

Cortisol

4

Growth hormone-releasing

hormone(GHRH or GRH)

49

GH

IGF-1

5

Prolactin release factor

Not

established

PRL

neurohormones

6

Somatostatin (Growth hormone

release-inhibiting hormone;

somatotropin release-inhibiting

hormone (GHRIH or SRIH)

14

GH (TSH, FSH,

ACTH)

IGK-1; T

3

andT

4

7

Prolactin- release-inhibiting

hormones (Dopamine and GAP)

(PRIH or PIH)

PRL

neurohormones

1

The hypothalamic hormone has a secondary or lesser effect on the hormones in parentheses.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

33

Biochemistry and

Disorders of

Hormones of the

Hypothalamic and

pituitary gland

(hypothalamus

and pituitary axis

2. Hormones of the pituitary gland

Prof. Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

34

Lecture 4

Sunday 26/2

2. Hormones of the Pituitary gland

The pituitary gland, also known

as the hypophysis, is a roundish

organ that lies immediately

beneath the hypothalamus.

Careful examination of the

pituitary gland reveals that it

composed of two distinctive

parts:

•

The

anterior pituitary

(adenohypophysis) is a

classical gland composed predominantly of cells that secrete protein hormones.

•

The

posterior pituitary

(neurohypophysis) is not really an organ, but an extension

of the hypothalamus. It is composed largely of the axons of hypothalamic neurons

which extend downward as a large bundle

behind the anterior pituitary.

The target cells for most of the hormones produced in

these tissues are themselves endocrine cells.

The pituitary gland is often called the "master

gland" of the body. The anterior and posterior pituitary

secretes a number of hormones that collectively

influence all cells and affect virtually all physiologic

processes.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

35

Table: The major hormones synthesized and secreted by the pituitary gland, along

with summary statements about their major target organs and physiologic effects.

Hormone

Major target

organ(s)

Major Physiologic Effects

Growth hormone

Liver, adipose

tissue

Promotes growth (indirectly),

control of protein, lipid and

carbohydrate metabolism

Thyroid-stimulating h.

Thyroid gland

Stimulates secretion of thyroid

hormones

Adrenocorticotropic h. Adrenal gland

(cortex)

Stimulates secretion of

glucocorticoids

Prolactin

Mammary gland

Milk production

Luteinizing hormone

Ovary and testis

Control of reproductive function

A

n

te

ri

o

r

P

it

u

it

a

ry

Follicle-stimulating h.

Ovary and testis

Control of reproductive function

Antidiuretic hormone

Kidney

Conservation of body water

P

o

s

te

ri

o

r

P

it

u

it

a

ry

Oxytocin

Ovary and testis

Stimulates milk ejection and uterine

contractions

As seen in the table above, the anterior pituitary synthesizes and secreted six major

hormones. Individual cells within the anterior pituitary secrete a single hormone (or

possibly two in some cases). Thus, the anterior pituitary contains at least six distinctive

endocrinocytes

The cells that secrete thyroid-stimulating hormone do not also secrete growth hormone,

and they have receptors for thyroid-releasing hormone, not growth hormone-releasing

hormone.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

36

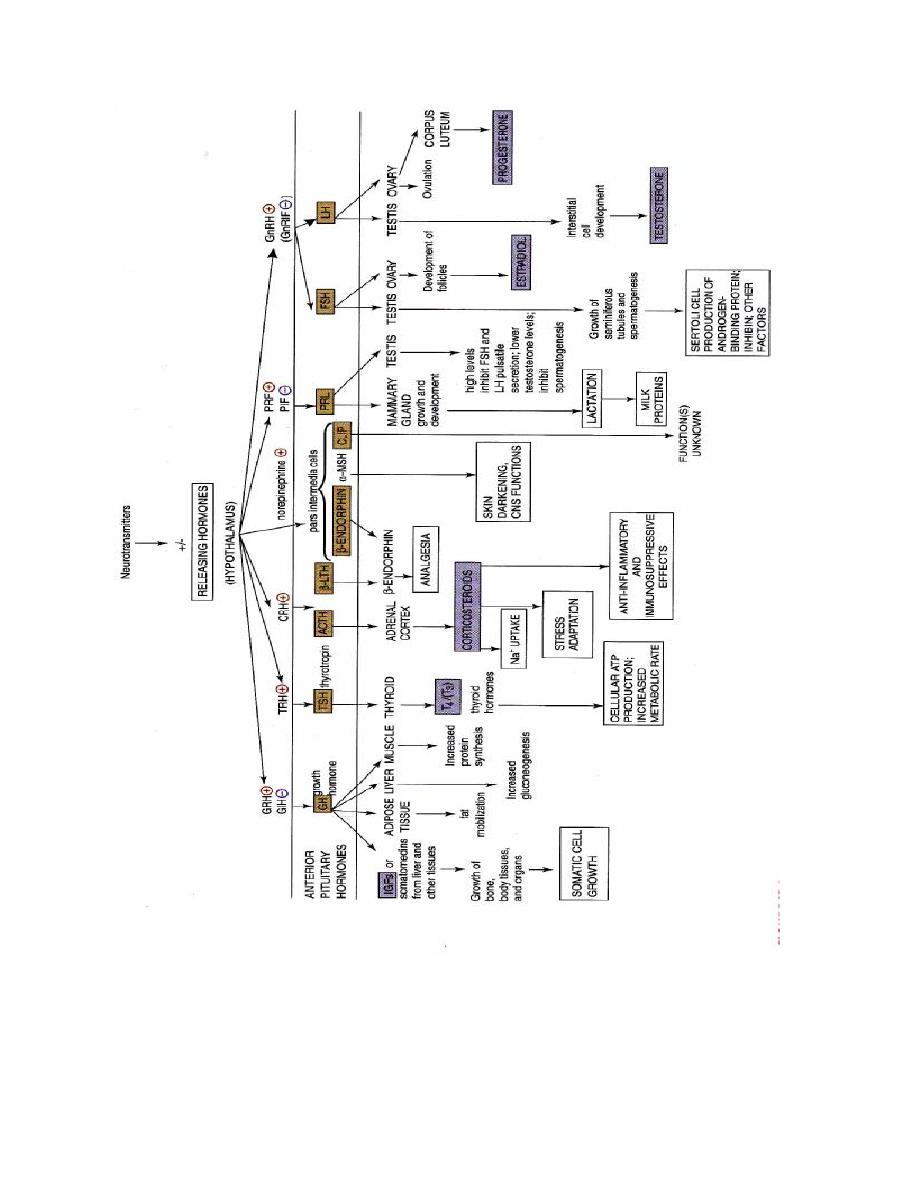

Overview of anterior pituitary hormones with hypothalamic releasing

hormones and their actions

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

37

Anterior Pituitary Hormones

1. Growth Hormone

Growth hormone, also known as somatotropin, is a

protein hormone of about 190 amino acids that is

synthesized and secreted by cells called somatotrophs in

the anterior pituitary. It is a major participant in control of

several complex physiologic processes, including growth

and metabolism. Growth hormone is also of considerable

interest as a drug used in both humans and animals.

Physiologic Effects of Growth Hormone

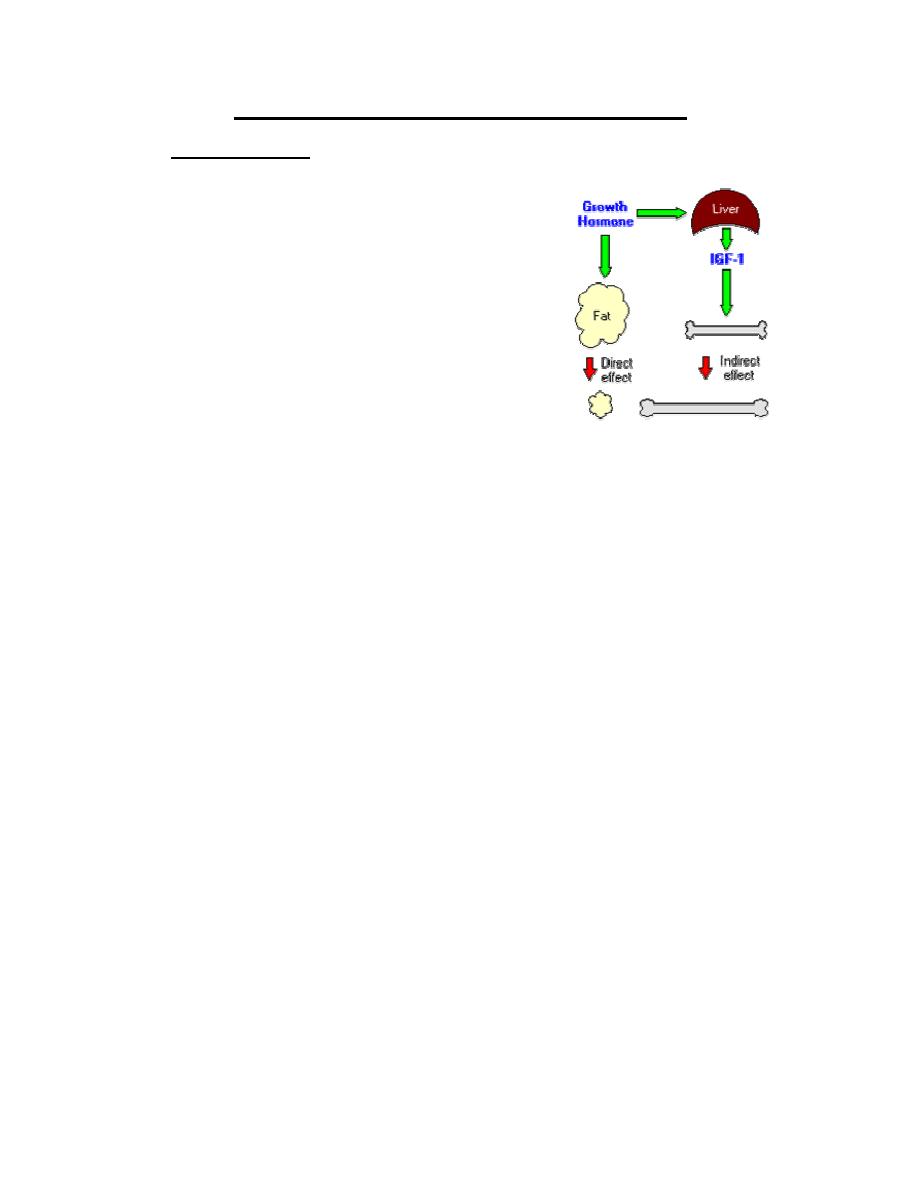

A critical concept in understanding growth hormone

activity is that it has two distinct types of effects:

•

Direct effects

are the result of growth hormone binding its receptor on target cells.

Fat cells (adipocytes), for example, have growth hormone receptors, and growth

hormone stimulates them to break down triglyceride and suppresses their ability to

take up and accumulate circulating lipids.

Indirect effects

are mediated primarily by a insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), a

hormone that is secreted from the liver and other tissues in response to growth hormone.

A majority of the growth promoting effects of growth hormone is actually due to IGF-1

acting on its target cells. IGF-1 also appears to be the key player in muscle growth. It

stimulates amino acid uptake and protein synthesis in muscle and other tissues.

Metabolic Effects

•

Protein metabolism: In general, growth hormone stimulates protein anabolism in

many tissues. This effect reflects increased amino acid uptake, increased protein

synthesis and decreased oxidation of proteins.

•

Fat metabolism: Growth hormone enhances the utilization of fat by stimulating

triglyceride breakdown and oxidation in adipocytes.

•

Carbohydrate metabolism: Growth hormone is one of a battery of hormones that

serves to maintain blood glucose within a normal range. Growth hormone is often

said to have anti-insulin activity, because it suppresses the abilities of insulin to

stimulate uptake of glucose in peripheral tissues and enhance glucose synthesis in

the liver.

•

Mineral metabolism: promotes a positive calcium, magnesium and phosphate

balance and causes the retention of Na

+

, K

+

and Cl

-

.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

38

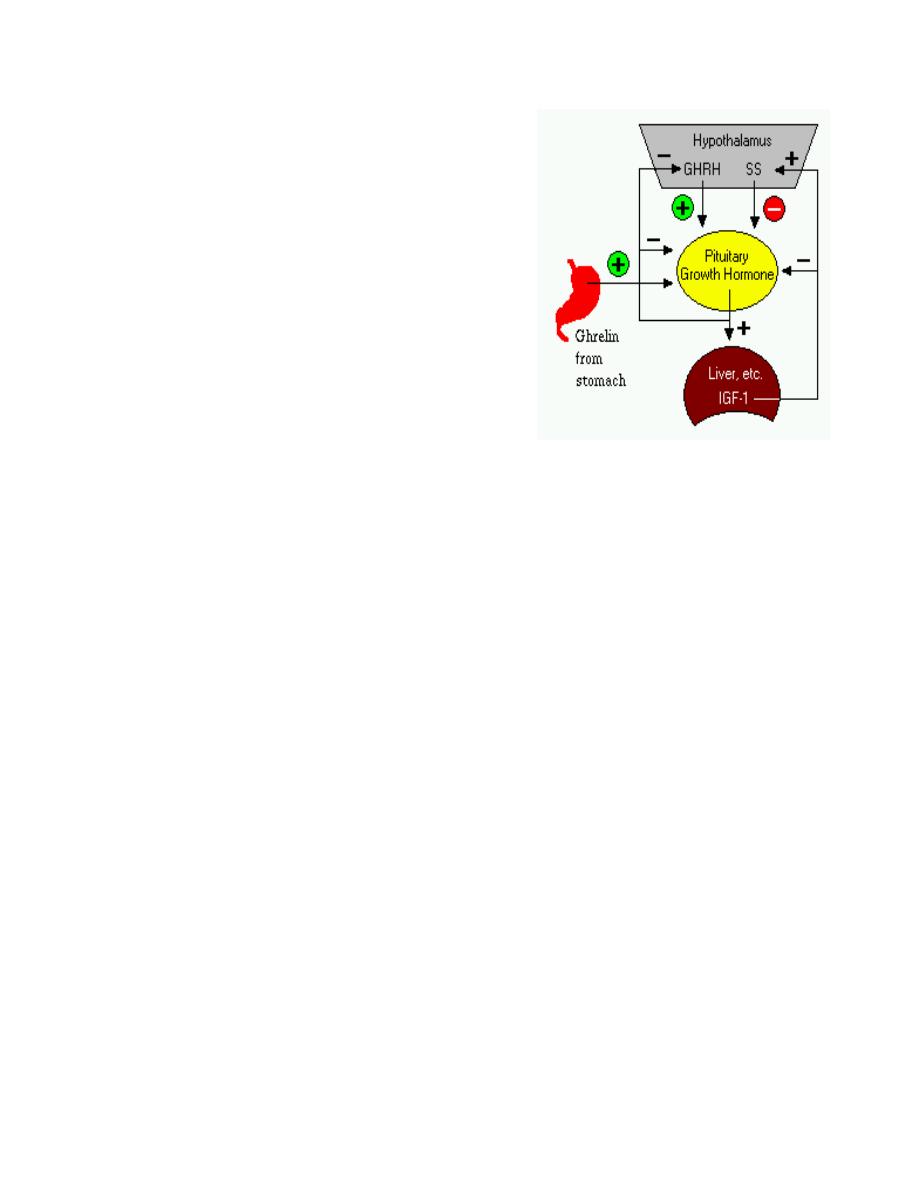

Control of Growth Hormone Secretion

Production of growth hormone is modulated by many

factors, including stress, exercise, nutrition, sleep and

growth hormone itself. However, its primary controllers

are two hypothalamic hormones and one hormone from

the stomach:

•

Growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH)

is a hypothalamic peptide that stimulates both

the synthesis and secretion of growth hormone.

•

Somatostatin (SS) is a peptide produced by

several tissues in the body, including the

hypothalamus. Somatostatin inhibits growth

hormone release in response to GHRH and to

other stimulatory factors such as low blood glucose concentration.

•

Ghrelin is a peptide hormone secreted from the stomach. Ghrelin binds to

receptors on somatotrophs and potently stimulates secretion of growth hormone.

Growth hormone secretion is also part of a negative feedback loop involving IGF-1.

High blood levels of IGF-1 lead to decreased secretion of growth hormone not only by

directly suppressing the somatotroph, but by stimulating release of somatostatin from the

hypothalamus.

Growth hormone also feeds back to inhibit GHRH secretion and probably has a direct

(autocrine) inhibitory effect on secretion from the somatotroph.

Integration of all the factors that affect growth hormone synthesis and secretion lead to a

pulsatile pattern of release. In children and young adults, the most intense period of growth

hormone release is shortly after the onset of deep sleep.

Disease States

A deficiency state can result not only from a deficiency in production of the hormone, but in

the target cell's response to the hormone.

Clinically, deficiency in growth hormone or receptor defects are known as growth

retardation or dwarfism. The manifestation of growth hormone deficiency depends upon

the age of onset of the disorder and can result from either heritable or acquired disease.

The effect of excessive secretion of growth hormone is also very dependent on the age of

onset and is seen as two distinctive disorders:

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

39

•

Gigantism is the result of excessive growth hormone secretion that begins in young

children or adolescents. It is a very rare disorder, usually resulting from a tumor of

somatotropes.

•

Acromegaly results from excessive secretion of growth hormone in adults. The

excessive growth hormone and IGF-1 also lead to metabolic derangements,

including glucose intolerance.

2. Thyroid Stimulating Hormone

Thyroid-stimulating hormone, also known as thyrotropin, is secreted from cells in

the anterior pituitary called thyrotrophs, finds its receptors on epithelial cells in the

thyroid gland, and stimulates that gland to synthesize and release thyroid

hormones.

TSH is a glycoprotein hormone composed of

two subunits, which are non-covalently bound

to one another. The alpha subunit of TSH is

also present in two other pituitary glycoprotein

hormones, follicle-stimulating hormone and

luteinizing hormone. In other words, TSH is composed of

alpha subunit bound to the TSH beta subunit, and TSH

associates only with its own receptor. Free alpha and beta

subunits have essentially no biological activity.

TSH has several acute effects on thyroid function. These

occur in minutes and involve increases of all phases of T

3

and T

4

biosynthesis. TSH also has several chronic effects

on the thyroid. These require several days and include

increases in the synthesis of proteins, phospholipids, and

nucleic acids and in the size of number of thyroid cells.

The most important controller of TSH secretion is thyroid-releasing hormone.

Secretion of thyroid-releasing hormone, and hence, TSH, is inhibited by high blood

levels of thyroid hormones in a classical negative feedback loop.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

40

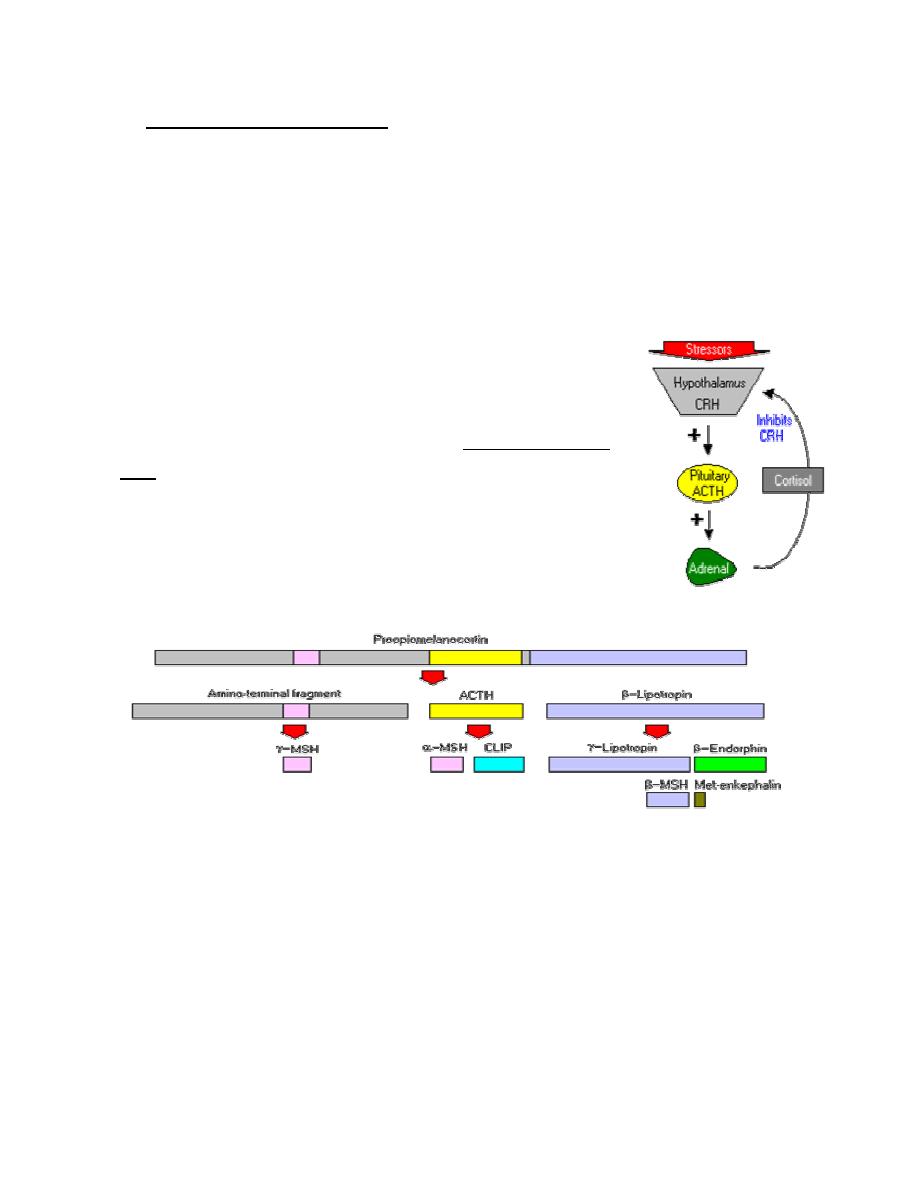

3. Adrenocorticotropic Hormone

Adrenocorticotropic hormone, stimulates the adrenal cortex by enhancing the

conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone. More specifically, it stimulates secretion

of glucocorticoids such as cortisol, and has little control over secretion of aldosterone,

the other major steroid hormone from the adrenal cortex. Another name for ACTH is

corticotropin.

ACTH is secreted from the anterior pituitary in response to corticotropin-releasing

hormone from the hypothalamus. Corticotropin-releasing hormone

is secreted in response to many types of stress, which makes sense

in view of the "stress management" functions of glucocorticoids.

Corticotropin-releasing hormone itself is inhibited by

glucocorticoids, making it part of a classical negative feedback

loop.

Within the pituitary gland, ACTH is produced in a process that

also generates several other hormones. A large precursor protein

named proopiomelanocortin (POMC) is synthesized and

proteolytically chopped into several fragments as depicted below.

The major attributes of the hormones other than ACTH that are produced in this process

are summarized as follows:

•

Lipotropin: Originally described as having weak lipolytic effects, its major

importance is as the precursor to beta-endorphin.

•

Beta-endorphin and Met-enkephalin: Opioid peptides with pain-alleviation and

euphoric effects.

•

Melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH): Known to control melanin pigmentation

in the skin of most vertebrates.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

41

4. Prolactin

Prolactin is a single-chain protein hormone closely related to growth hormone. It is

secreted by so-called lactotrophs in the anterior pituitary. It is also synthesized and

secreted by a broad range of other cells in the body.

Prolactin is synthesized as a prohormone. Following cleavage of the signal peptide, the

length of the mature hormone is between 194 and 199 amino acids, depending on

species. Hormone structure is stabilized by three intramolecular disulfide bonds.

Overall, several hundred different actions have been reported for prolactin in various

species. Some of its major effects are:

1. Mammary Gland Development, Milk Production and Reproduction

2. Effects on Immune Function

The prolactin receptor is widely expressed by immune cells, and some types of

lymphocytes synthesize and secrete prolactin. These observations suggest that prolactin

may act as an autocrine or paracrine modulator of immune activity..

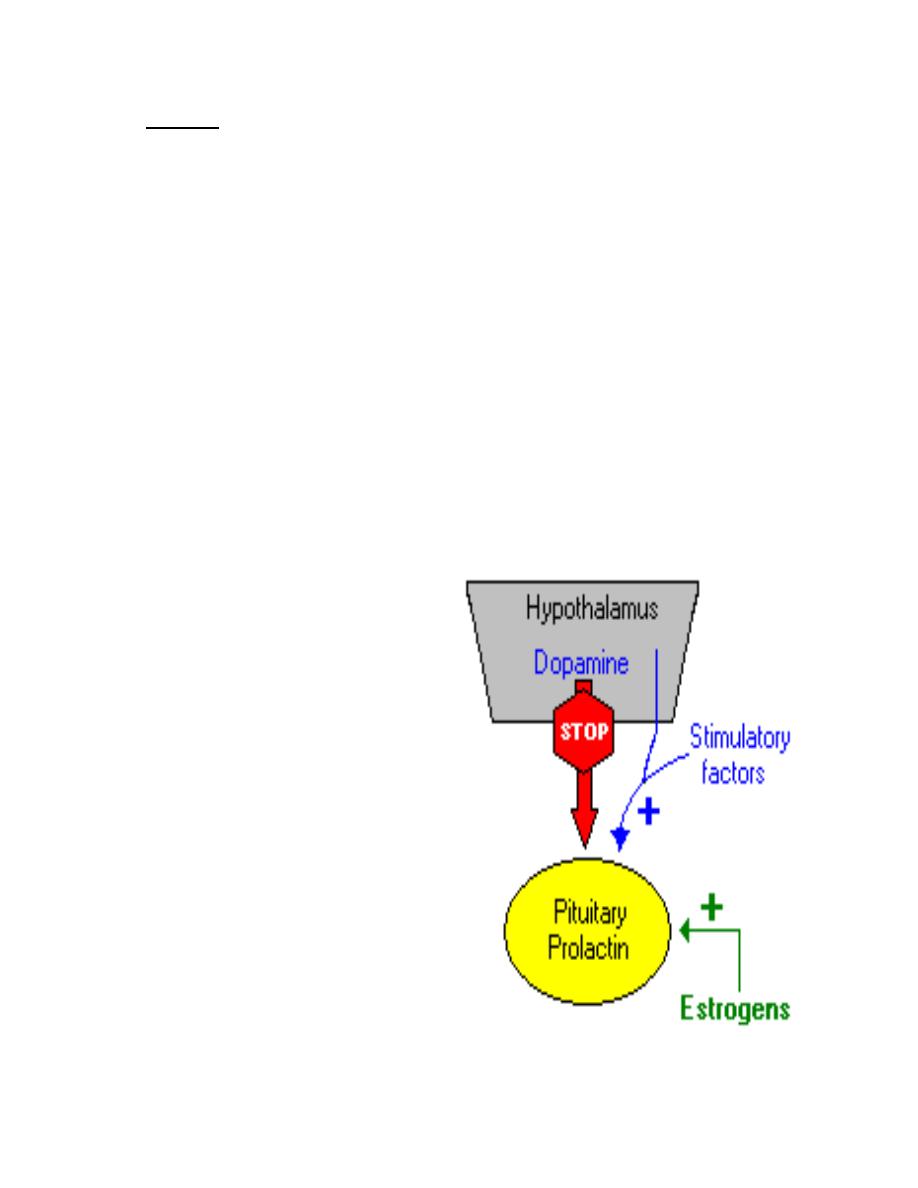

Control of Prolactin Secretion

In contrast to what is seen with all the

other pituitary hormones, the

hypothalamus suppresses prolactin

secretion from the pituitary.

Dopamine serves as the major prolactin-

inhibiting factor or brake on prolactin

secretion. In addition to inhibition by

dopamine, prolactin secretion is positively

regulated by several hormones, including

thyroid-releasing hormone, gonadotropin-

releasing hormone and vasoactive

intestinal polypeptide.

Estrogens provide a well-studied

positive control over prolactin synthesis

and secretion.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

42

5. Gonadotropins: Luteinizing and Follicle Stimulating Hormones

Luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) are called

gonadotropins because stimulate the gonads - in males, the testes, and in females,

the ovaries. As described for thyroid-simulating hormone, LH and FSH are large

glycoproteins composed of alpha and beta subunits. The alpha subunit is identical in all

three of these anterior pituitary hormones, while the beta subunit is unique for each

hormone with the ability to bind its own receptor.

a.

Luteinizing Hormone

In both sexes, LH stimulates secretion of sex steroids from the gonads. In the testes,

it stimulates the synthesis and secretion of testosterone. The ovary respond to LH

stimulation by secretion of testosterone, which is converted into estrogen by adjacent

granulosa cells.

LH is required for continued development and function of corpora lutea. The name

luteinizing hormone derives from this effect of inducing luteinization of ovarian follicles.

b.

Follicle-Stimulating Hormone

As its name implies, FSH stimulates the maturation of ovarian follicles. FSH is also

critical for sperm production. It supports the function of Sertoli cells, which in turn

support many aspects of sperm cell maturation.

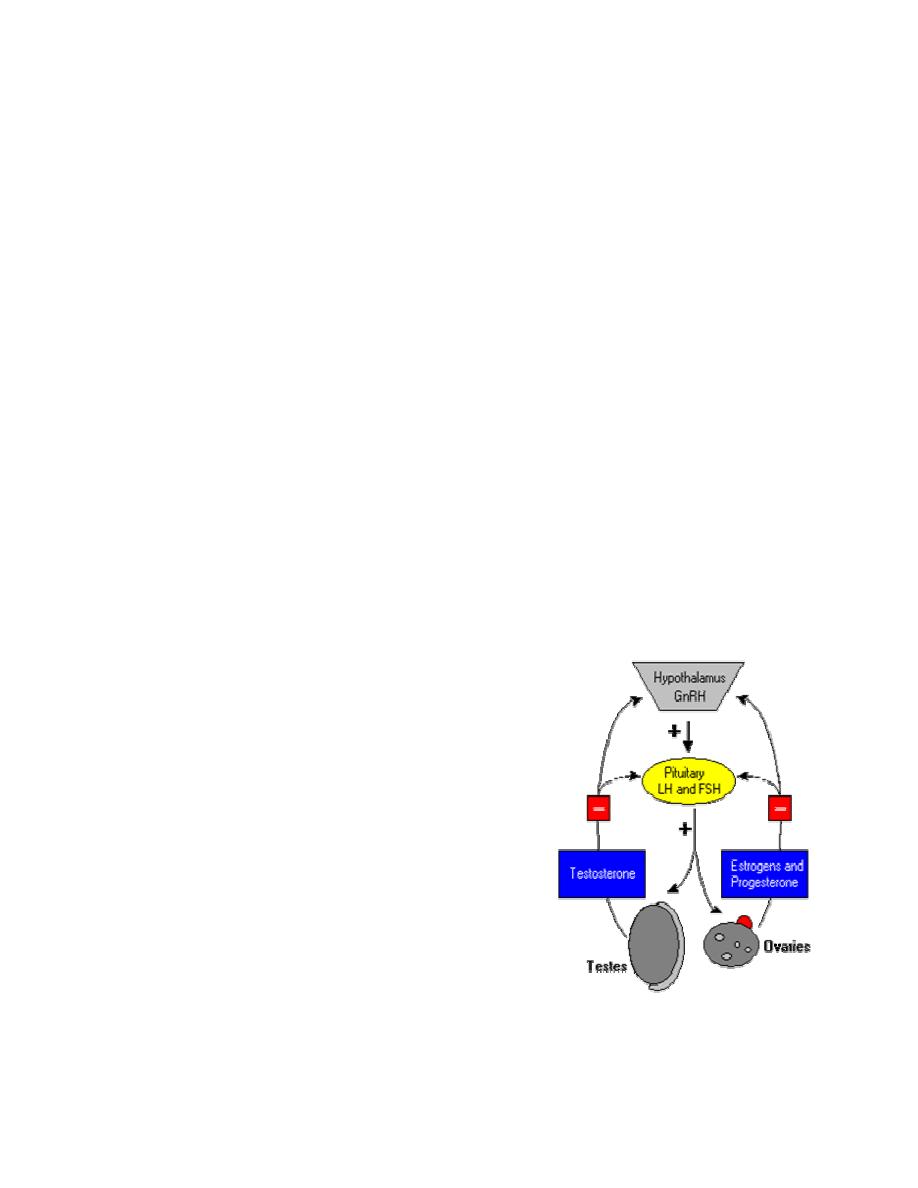

Control of Gonadotropin Secretion

The principle regulator of LH and FSH secretion is

gonadotropin-releasing hormone or GnRH (also

known as LH-releasing hormone). In a classical

negative feedback loop, sex steroids inhibit secretion of

GnRH and also appear to have direct negative effects

on gonadotrophs.

This regulatory loop leads to pulsatile secretion of LH

and, to a much lesser extent, FSH. Numerous

hormones influence GnRH secretion, and positive and

negative control over GnRH and gonadotropin secretion

is actually considerably more complex than described in

the figure. For example, the gonads secrete at least two additional hormones - inhibin and

activin , which selectively inhibit and activate FSH secretion from the pituitary.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

43

Posterior Pituitary Hormones

1. Antidiuretic Hormone (Vasopressin)

Roughly, 60% of the mass of the body is water, and despite wide

variation in the amount of water taken in each day, body water

content remains incredibly stable. Such precise control of body

water and solute concentrations is a function of several hormones

acting on both the kidneys and vascular system, but there is no doubt

that antidiuretic hormone is a key player in this process.

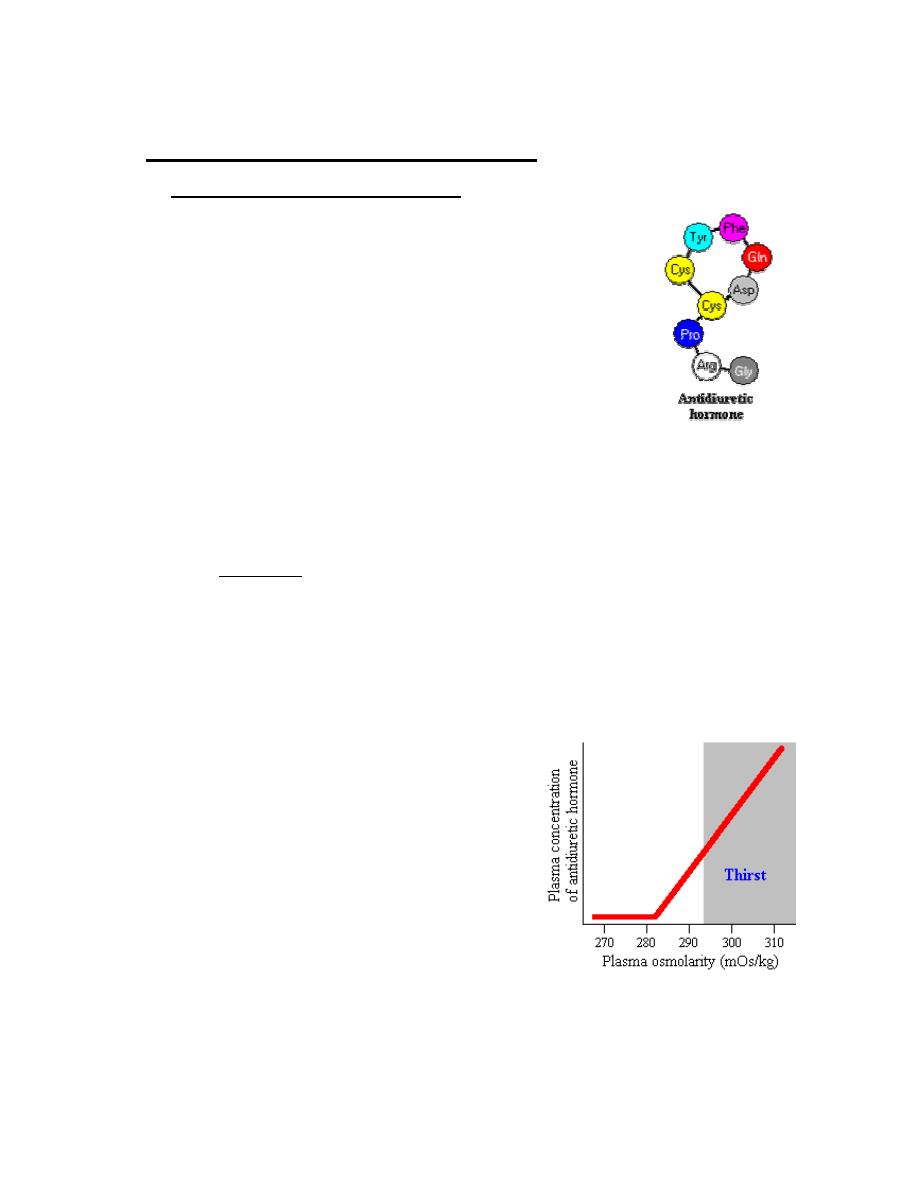

Antidiuretic hormone, also known as vasopressin, is a nine

amino acid peptide secreted from the posterior pituitary.

Physiologic Effects of Antidiuretic Hormone

The single most important effect of antidiuretic hormone is to conserve body water by

reducing the output of urine.

Antidiuretic hormone stimulates water reabsorbtion by stimulating insertion of "water

channels" or aquaporins into the membranes of kidney tubules. These channels transport

solute-free water through tubular cells and back into blood, leading to a decrease in

plasma osmolarity and an increase osmolarity of urine.

Control of Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion

1. The most important variable regulating antidiuretic hormone secretion is

plasma osmolarity, or the concentration of solutes in blood. When plasma

osmolarity is below a certain threshold, the

osmoreceptors are not activated and antidiuretic

hormone secretion is suppressed. When

osmolarity increases above the threshold, the

ever-alert osmoreceptors recognize this and

stimulate the neurons that secrete antidiuretic

hormone. As seen the figure, antidiuretic

hormone concentrations rise steeply and linearly

with increasing plasma osmolarity.

2. Secretion of antidiuretic hormone is also simulated by decreases in blood

pressure and volume, conditions sensed by stretch receptors in the heart and

large arteries. Changes in blood pressure and volume are not nearly as sensitive a

stimulator as increased osmolarity, but are nonetheless potent in severe conditions.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

44

For example, Loss of 15 or 20% of blood volume by hemorrhage results in massive

secretion of antidiuretic hormone.

Another potent stimulus of antidiuretic hormone is nausea and vomiting.

Disease States

The most common disease of man and animals related to antidiuretic hormone is diabetes

insipidus. This condition can arise from either of two situations:

•

Hypothalamic ("central") diabetes insipidus

results from a deficiency in

secretion of antidiuretic hormone from the posterior pituitary. Causes of this disease

include head trauma, and infections or tumors involving the hypothalamus.

•

Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus

occurs when the kidney is unable to respond to

antidiuretic hormone. Most commonly, this results from some type of renal disease,

but mutations in the ADH receptor gene or in the gene encoding aquaporin-2 have

also been demonstrated in affected humans.

The major sign of either type of diabetes insipidus is excessive urine production.

Some human patients produce as much as 16 liters of urine per day! If adequate water is

available for consumption, the disease is rarely life-threatening, but withholding water can

be very dangerous.

2. Oxytocin

Oxytocin in a nine amino acid peptide that is synthesized in hypothalamic neurons and

transported down axons of the posterior pituitary for secretion into

blood. Oxytocin differs from antidiuretic hormone in two of the nine

amino acids. Both hormones are packaged into granules and

secreted along with carrier proteins called neurophysins.

Control of Oxytocin Secretion

A number of factors can inhibit oxytocin release, among them acute

stress. For example, oxytocin neurons are repressed by

catecholamines, which are released from the adrenal gland in response to many types of

stress, including fright.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

45

Clinical correlation

Testing Activity of the Anterior Pituitary

Releasing hormones and chemical analogs, particularly of the smaller peptides, are now

routinely synthesized. The gonadotropin-releasing hormone, a decapeptide, is available for

use in assessing the function of the anterior pituitary. This is of importance when a disease

situation may involve either the hypothalamus, the anterior pituitary, or the end organ.

Infertility is an example of such a situation. What needs to be assessed in which organ is

at fault in the hormonal cascade. Initially, the end organ, in this case the gonads, must be

considered. This can be accomplished by injecting the anterior pituitary hormone LH or

FSH. If sex hormone secretion is elicited, then the ultimate gland would appear to be

functioning properly. Next, the anterior pituitary would need to be analyzed. This can be

done by i.v. administration of synthetic GnRH; by this route, GnRH can gain access to the

gonadotropic cells of the anterior pituitary and elicit secretion of LH and FSH. Routinely,

LH levels are measured in the blood as a function of time after the injection. These levels

are measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA) in which radioactive LH or hCG is displaced

from binding to an LH-binding protein by LH in the serum sample. The extent of the

competition is proportional to the amount of LH in the serum. In this way a progress of

response is measured that will be within normal limits or clearly deficient. If the response is

deficient, the anterior pituitary cells are not functioning normally and are the cause of the

syndrome. On the other hand, normal pituitary response to GnRH would indicate that the

hypothalamus was non-functional. Such a finding would prompt examination of the

hypothalamus for conditions leading to insufficient availability/production of releasing

hormones. Obviously, the knowledge of hormone structure and the ability to synthesize

specific hormones permits the diagnosis of these disease states.

Source: Marshall, J. C. and Barkan, A. L., "Disorders of the hypothalamus and anterior

pituitary. In: W. N. Kelley (Ed.), Internal Medicine." New York: Lippincott, 1989, p. 2759.

Conn, P. M. "The molecular basis of gonadotropin-releasing hormone action". Endocr.

Rev. 7:3, 1986.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

46

Clinical correlation

Hypopituitarism

The hypothalamus is connected to the anterior pituitary by a delicate stalk that contains

the portal system through which releasing hormones, secreted from the hypothalamus,

gain access to the anterior pituitary cells. In the cell membranes of these cells are specific

receptors for releasing hormones. In most cases, different cells express deferent releasing

hormone receptors. The connection between the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary can

be disrupted by trauma or tumors. Trauma can occur in automobile accidents or other local

damaging events that may result in severing of the stalk, thus preventing the releasing

hormones from reaching their target anterior pituitary cells. When this happens, the

anterior pituitary cells no longer have their signaling mechanism for the release of anterior

pituitary hormones. In the case of tumors of the pituitary gland, all of the anterior pituitary

hormones may not be shut off to the same degree or the secretion of some may disappear

sooner than others.

In any case, if the hypopituitarism occurs, this condition may result in a life-threatening

situation in which the clinician must determine the extent of loss of pituitary hormones,

especially ACTH. Posterior pituitary hormones (Oxytocin and vasopressin) may also be

lost, precipitating a problem of excessive urination (vasopressin deficiency) that must be

addressed. The usual therapy involves administration of the end-organ hormones, such

as, thyroid hormone, cortisol, sex hormones, and progestin; with female patients it is also

necessary to maintain the ovarian cycle. These hormones can be easily administered in

the oral form. Growth hormone deficiency is not a problem in the adult but would be an

important problem in a growing child.

The patient must learn to anticipate needed increases of cortisol in the face of stressful

situations. Fortunately, these patients are usually maintained in reasonably good condition.

Source: Marshall, J. C. and Barkan, A. L., "Disorders of the hypothalamus and anterior

pituitary. In: W. N. Kelley (Ed.), Internal Medicine." New York: Lippincott, 1989, p.

2159.Robinson,A.G."Disorders of the posterior pituitary". In: W. N. Kelley(Ed.), Internal

Medicine. New York:

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

47

Question : Hypopituitarism may result from trauma, such as an automobile accident

severing the stalk connecting the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary, or from tumors of

the pituitary gland. In trauma, usually all of the releasing hormones from hypothalamus fail

to reach the anterior pituitary. With a tumor of the gland, some or all of the pituitary

hormones may be shut off. Posterior pituitary hormones may also be lost. Hypopituitarism

can be life threatening. Usual therapy is administration of end-organ hormones in oral

form.

1) If the stalk between the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary is severed, the pituitary

would fail to cause the ultimate release of all of the following hormones except :

a) ACTH.

b) estradiol.

c) oxytocin.

d) testosterone.

e) thyroxine.

Answers:

1) C Oxytocin is released from posterior pituitary. A, B, D, and E all require releasing

hormones from hypothalamus for anterior pituitary to release them.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

48

Lecture 5

Sunday 4/3

Biochemistry and Disorder of Hormones of the

Thyroid and Parathyroid Glands

1.

The Thyroid Gland

The thyroid gland (Greek thyros “shield”) is shaped like a shield and lies just below

the Adam’s apple in the front of the neck.

The thyroid gland secretes thyroxine and smaller amounts of triiodothyronine (T3),

which stimulate oxidative respiration in most cells in the body and, in so doing, help

set the body’s basal metabolic rate. In children, these thyroid hormones also promote

growth and stimulate maturation of the central nervous system. Children with

underactive thyroid glands are therefore stunted in their growth and suffer severe

mental retardation, a condition called cretinism. This differs from pituitary dwarfism,

which results from inadequate GH and is not associated with abnormal intellectual

development.

People who are hypothyroid (whose secretion of thyroxine is too low) can take

thyroxine orally, as pills. Only thyroxine and the steroid hormones (as in

contraceptive pills), can be taken orally because they are nonpolar and can pass

through the plasma membranes of intestinal epithelial cells without being digested.

The thyroid gland also secretes calcitonin, a peptide hormone that plays a role in

maintaining proper levels of calcium (Ca++) in the blood. When the blood Ca++

concentration rises too high, calcitonin stimulates the uptake of Ca++ into bones, thus

lowering its level in the blood.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

49

Thyroid Hormones

1. Thyroxin (T4) and triiodotyonine T3

Biochemistry of Thyroid Hormones

Thyroid hormones are derivatives of the amino acid tyrosine bound covalently to

iodine. The two principal thyroid hormones are:

•

thyroxine (T

4

or L-3,5,3',5'-tetraiodothyronine)

•

triiodotyronine (T

3

or L-3,5,3'-triiodothyronine).

Thyroid hormones are basically two tyrosines linked together with the critical

addition of iodine at three or four positions on the aromatic rings. The number

and position of the iodines is important. Several other iodinated molecules are

generated that have little or no biological activity; so called "reverse T

3

"

A large majority of the thyroid hormone secreted from the thyroid gland is T

4

,

but T

3

is the considerably more active hormone. Although some T

3

is also

secreted, the bulk of the T

3

is derived by deiodination of T

4

in peripheral tissues,

especially liver and kidney. Deiodination of T

4

also yields reverse T

3

, a molecule

with no known metabolic activity.

Thyroid hormones are poorly soluble in water, and more than 99% of the T

3

and T

4

circulating in blood is bound to carrier proteins. The principle carrier of thyroid

hormones is thyroxine-binding globulin, a glycoprotein synthesized in the liver.

Another carrier is albumin.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

50

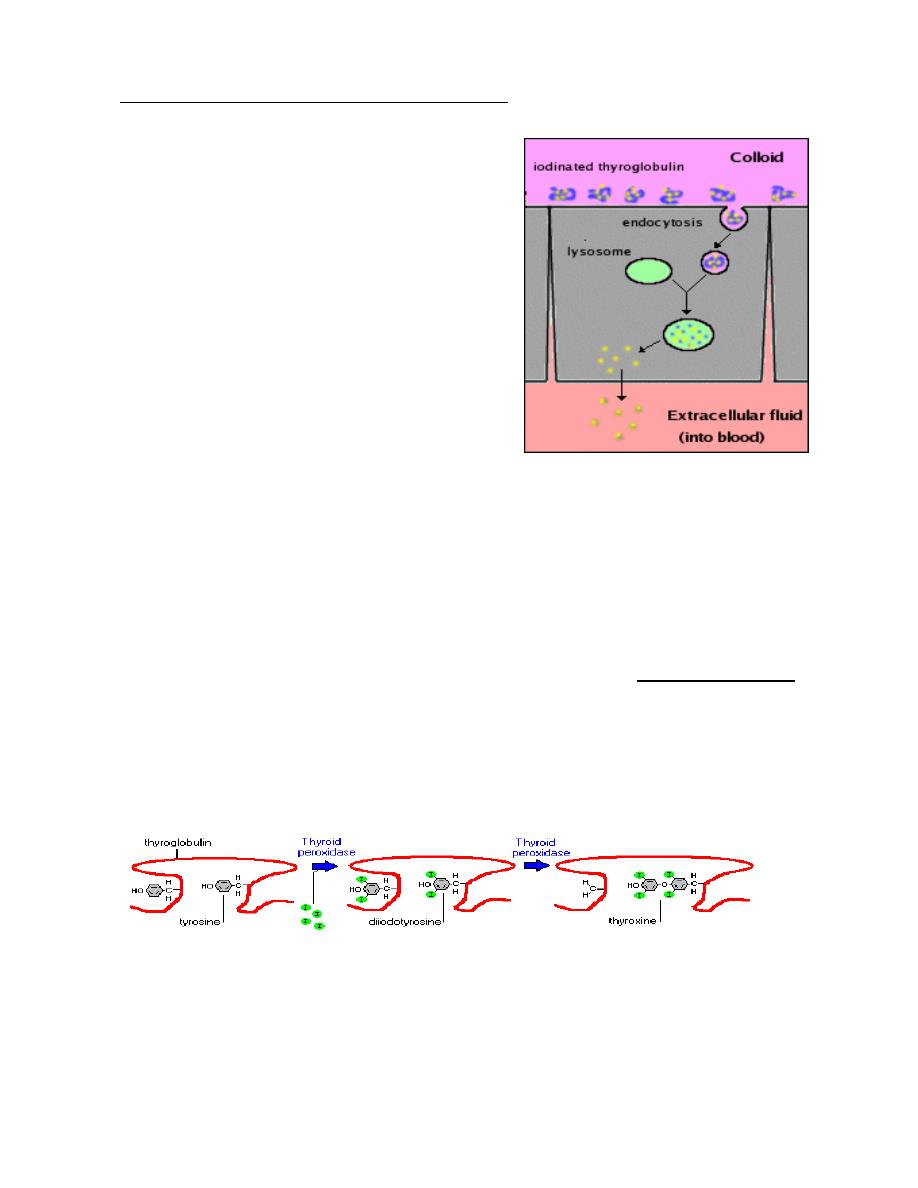

Synthesis and Secretion of Thyroid Hormones

The entire synthetic process occurs in three major steps:

•

Production and accumulation of the raw

materials

•

Fabrication or synthesis of the hormones on a

backbone or scaffold of precursor

•

Release of the free hormones from the

scaffold and secretion into blood

Raw materials:

•

Tyrosines are provided from a large

glycoprotein scaffold called thyroglobulin,.

A molecule of thyroglobulin contains 134 tyrosines, although only a handful of

these are actually used to synthesize T

4

and T

3

.

•

Iodine, or more accurately iodide (I

-

), is taken up from blood by thyroid epithelial

cells, which have on their outer plasma membrane an "iodine trap". Once inside

the cell, iodide is transported into the lumen of the follicle along with

thyroglobulin.

Fabrication of thyroid hormones is conducted by the enzyme thyroid peroxidase,

Thyroid peroxidase catalyzes two sequential reactions:

1. Iodination of tyrosines on thyroglobulin (also known as "organification of

iodide").

2. Synthesis of thyroxine or triiodothyronine from two iodotyrosines.

Thyroid hormones are excised from their thyroglobulin scaffold by digestion in

lysosomes of thyroid epithelial cells. Free thyroid hormones apparently diffuse out

of lysosomes, through the basal plasma membrane of the cell, and into blood where

they quickly bind to carrier proteins for transport to target cells.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

51

Control of Thyroid Hormone Synthesis and Secretion

Each of the processes described above appears to be stimulated by

thyroid-

stimulating hormone

from the anterior pituitary gland. Binding of TSH to its

receptors on thyroid epithelial cells stimulates synthesis of the iodine transporter,

thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin. When TSH levels are low, rates of thyroid

hormone synthesis and release diminish.

The thyroid gland is part of the

hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis, and

control of thyroid hormone secretion is

exerted by classical negative feedback.

Thyroid Hormone Receptors and

Mechanism of Action

Receptors for thyroid hormones are

intracellular DNA-binding proteins that

function as hormone-responsive

transcription factors, very similar

conceptually to the

receptors for steroid

hormones

.

Thyroid hormones enter cells through

membrane transporter proteins. A number of plasma membrane transporters have

been identified, some of which require ATP hydrolysis; the relative importance of

different carrier systems is not yet clear and may differ among tissues. Once inside

the nucleus, the hormone binds its receptor, and the hormone-receptor complex

interacts with specific sequences of DNA in the promoters of responsive genes.

The effect of receptor binding to DNA is to modulate gene expression, either by

stimulating or inhibiting transcription of specific genes.

Prof.Dr. Hedef Dhafir El-Yassin 2012

52

Metabolic Effects of Thyroid Hormones

Thyroid hormones have profound effects on many physiologic processes, such as

development, growth and metabolism. They stimulate diverse metabolic activities

most tissues, leading to an increase in basal metabolic rate. One consequence of

this activity is to increase body heat production, which seems to result, at least in

part, from increased oxygen consumption and rates of ATP hydrolysis. A few

examples of specific metabolic effects of thyroid hormones include:

•

Lipid metabolism: Increased thyroid hormone levels stimulate fat

mobilization, leading to increased concentrations of fatty acids in plasma. They

also enhance oxidation of fatty acids in many tissues. Finally, plasma

concentrations of cholesterol and triglycerides are inversely correlated with

thyroid hormone levels - one diagnostic indication of hypothyroidism is

increased blood cholesterol concentration.

•

Carbohydrate metabolism: Thyroid hormones stimulate almost all aspects of

carbohydrate metabolism, including enhancement of insulin-dependent entry of

glucose into cells and increased gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis to

generate free glucose.

Other Effects: A few additional, effects of thyroid hormones include:

•

On muscle: T3 increases glucose uptake by muscle cells it also stimulate

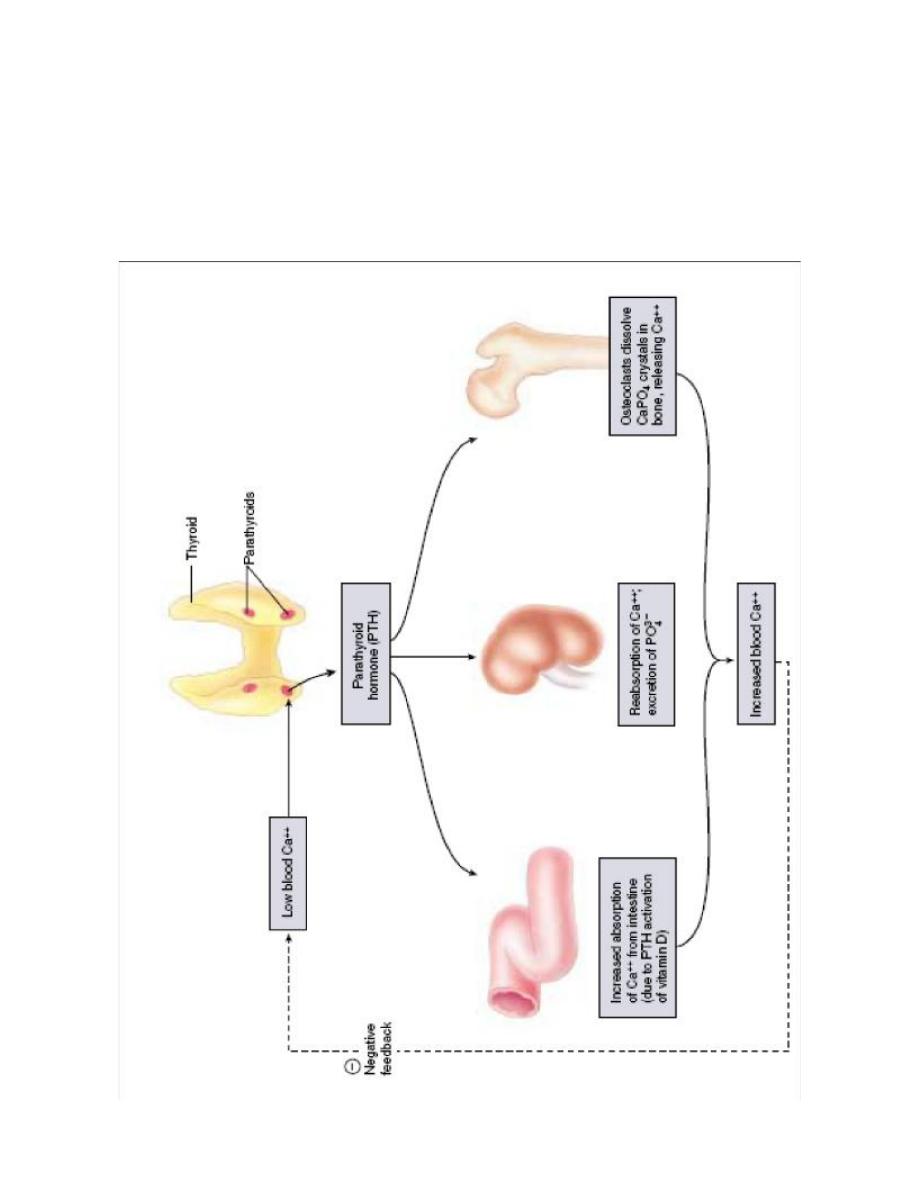

protein synthesis and therefore growth of muscle through its stimulatory