The Lymphatic System and Lymph Nodes

(1) Removes water, electrolytes, low-molecular-weight moieties (polypeptides,

cytokines, growth factors) and macromolecules (fibrinogen, albumin,

globulins, coagulation and fibrinolytic factors) from the interstitial fluid (ISF)

and returns them to the circulation.

Functions

:

(2) Permits the circulation of lymphocytes and other immune cells.

(3) Intestinal lymph (chyle) transports cholesterol, long-chain fatty acids,

triglycerides and the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K) directly to the

circulation, bypassing the liver.

Resting 1SF is negative (—2 to —6 mmH2O), whereas lymphatic pressures

are positive, indicating that lymph flows against a small pressure gradient. It is

believed that prograde lymphatic flow depends upon three mechanisms:

1. Transient

increases in interstitial pressure

secondary to muscular contraction and

external compression.

Mechanisms of lymph transport

:

2. The sequential contraction and relaxation of

lymphangions.

(Valves partition the

lymphatics into segments).

3. The prevention of reflux due to

valves

.

Lymphangions are believed to respond to increased lymph flow in much the

same way as the heart responds to increased venous return in that they increase their

contractility and stroke volume. Contractility is also enhanced by noradrenaline,

serotonin, certain prostaglandins and thromboxanes, and endothelin- 1. Lymphatics

may also modulate their own contractility through the production of nitric oxide and

other local mediators. Transport in the thoracic and right lymph ducts also depends

upon intrathoracic (respiration) and central venous (cardiac cycle) pressures.

Therefore, cardiorespiratory disease may have an adverse effect on lymphatic

function.

In summary, in the healthy limb, lymph flow is largely due to intrinsic lymphatic

contractility, although this is augmented by exercise, limb movement and external

compression. However, in lymphoedema, when the lymphatics are constantly

distended with lymph, these external forces assume a much more important

functional role.

Acute Lymphangitis

Definition:

It is infection spreading from a skin (wound, abrasion, laceration)

through the draining superficial lymphatic vessels to the draining lymph nodes. It is

usually seen in the extremities (upper and lower limbs).

Causative Microorganisms:

1) Group A B-haemolytic streptococci (streptococcus

pyogenes), 2) Staphylococcus aureus.

(1)

Red blushes or streaks in the skin

(correspond to inflamed lymphatics)

extending from the source of infection to the regional LNs.

Clinical Presentation:

(2)

Regional LNs

are enlarged and tender and may suppurate with abscess

formation, occasionally the infection bypasses one group to affect another at a

higher level (e.g, if the point of infection is the foot, an abscess may form in the

external iliac group of LNs rather than the superficial (lower) and deep inguinal

groups and because the point of infection may have healed and been forgotten,

by the time the mass appears it may be mistaken for an (appendix abscess).

(1)

Bed rest

(to reduce lymphatic drainage) with elevation of the affected limb (to

reduce swelling).

Treatment:

(2)

Antibiotics

. Failure to improve within 48 hours suggests inappropriate

antibiotic therapy, or the presence of undrained pus, or the presence of an

underlying systemic disorder (malignancy, immunodeficiency).

(3)

Drainage of an abscess

if it has formed.

(1)

Post-lymphatic oedema

. due to permanent lymphatic obstruction after

resolution of acute lymphangitis leading to persistent oedema. These patients

are prone to so-called acute inflammatory episodes (AlEs).

Complications:

(2)

Chronic lymphangitis

. Follows repeated attacks of acute lymphangitis.

(3)

Bacteraemia or Septicaemia

.

LYMPHOEDEMA

Definition

:

It is abnormal limb swelling due to the accumulation of increased

amounts of high protein ISF secondary to defective lymphatic drainage in the

presence of (near) normal net capillary filtration. So it is accumulation of fluid in

the interstitial spaces (extracellular fluid compartment), in the limbs it accumulates

mainly in the subcutaneous tissues.

1) Gradually

increasing circumference of the affected limb

(huge enlargement) with

multifolding of the skin.

Clinical Presentation

:

2) In the early stages the lymphoedema is

pitting

on pressure thus it simulates

ordinary oedema, but with time lymphoedema characteristically becomes Non-

pitting lymphoedema due to subcutaneous thickening with fibrous tissue being

worsened by recurring low grade lymphangitis and cellulitis. (Recurrent acute

infective episodes). In the early stages, lymphoedema will ‘pit’ and the patient

will report that the swelling is down in the morning. This represents a reversible

component to the swelling, which can be controlled. Failure to do so allows

fibrosis, dermal thickening and hyperkeratosis to occur.

3) Unlike other types of oedema, Iymphoedema characteristically involves the

foot

.

The contour of the ankle is lost through infilling of the submalleolar depressions,

a ‘buffalo hump’ forms on the

dorsum of the foot, the toes appear ‘square’ due to confinement of footwear, and

the skin on the dorsum of the toes cannot be pinched due to subcutaneous

fibrosis (Stemmer’s sign) Lymphoedema usually spreads proximally to knee

level and less commonly affects the whole leg.

4)

Lymphangiomas

are dilated dermal lymphatics that ‘blister’ onto the skin

surface. The fluid is usually clear but may be bloodstained and, in the long term,

they thrombose and fibrose, forming hard nodules and raising concerns about

malignancy. If lymphangiomas are < 5 cm across, they are termed

lymphangioma circumscriptum

, and if they are more widespread, they are termed

lymphangioma diffusum

. If they form a reticulate pattern of ridges then it has

been termed

lymphoedema ab igne

. Lymphangiomas frequently weep

(lymphorrhoea, chylorrhoea), causing skin maceration and they act as a portal for

infection.

5)

Lymphangiosarcoma

was originally described in post-mastectomy oedema

(Stewart—Treves syndrome) and affects around 0.5% of patients at a mean onset

of 10 years. However, lymphangiosarcoma can develop in any longstanding

lymphoedema, but usually takes longer to manifest (20 years). It presents as

single or multiple bluish/red skin and subcutaneous nodules that spread to form

satellite lesions that may then become confluent.

6)

Ulceration, non-healing bruises, and raised purple-red nodules

should lead to

suspicion of malignancy.

7)

Constant dull ache, even severe pain or Burning and bursting

sensations or Pins

and needles.

8)

Sensitivity to heat

.

9)

General tiredness and debility

.

10)

Skin problems

, including dehydration, flakiness, weeping, excoriation and

breakdown. Chronic eczema, fissuring, verrucae and papillae (warts) are

frequently seen in advanced disease. Ulceration is unusual, except in the

presence of chronic venous insufficiency.

11)

Immobility, leading to obesity and muscle wasting

.

12)

Backache and joint problems

.

13)

Fungal infection

of the skin (dermatophytosis) and nails (onychomycosis)

Athlete’s foot.

Pathophysiology:

The 1SF compartment (10-12 litres in a 70-kg man) constitutes 50% of the

wet weight of skin and subcutaneous tissues and, in order for oedema to be

clinically detectable, its volume has to double. About 8 litres (protein concentration

approximately 20-30g/L, similar to ISF) of lymph is produced each day and travels

in afferent lymphatics to lymph nodes. There, the volume is halved and the protein

concentration doubled, resulting in 4 litres of lymph re-entering the venous

circulation each day via efferent lymphatics. In one sense, all oedema is

lymphoedema in that it results from an inability of the lymphatic system to clear the

ISF compartment. However, in most types of oedema this is because capillary

filtration rate is pathologically high and overwhelms a normal lymphatic system,

resulting in the accumulation of low-protein oedema fluid. In contrast, in true

lymphoedema, when the primary problem is in the lymphatics, capillary filtration is

normal and the oedema fluid is relatively high in protein. Of course, in a significant

number of patients with oedema there is both abnormal capillary filtration and

abnormal lymphatic drainage. Lymphoedema

results from

lymphatic 1-aplasia, 2-

hypoplasia, 3-dysmotility (reduced contractility with or without valvular

insufficiency), 4-obliteration by inflammatory, infective or neoplastic processes, or

5-surgical extirpation. Whatever the primary abnormality, the resultant physical

and/or functional obstruction leads to lymphatic hypertension and distension, with

further secondary impairment of contractility and valvular competence.

Lymphostasis and lymphotension

lead to the accumulation in the ISF of fluid,

proteins, growth factors and other active peptide moieties, glycosaminoglycans and

particulate matter, including bacteria. As a consequence, there is increased collagen

production by fibroblasts, an accumulation of inflammatory cells (predominantly

macrophages and lymphocytes) and activation of keratinocytes. The end result is

protein-rich oedema fluid, increased deposition of ground substance, subdermal

fibrosis and dermal thickening and proliferation. Lymphoedema, unlike all other

types of oedema, is confined to the epifascial space. Although muscle

compartments may be hypertrophied owing to the increased work involved in limb

movement, they are characteristically free of oedema.

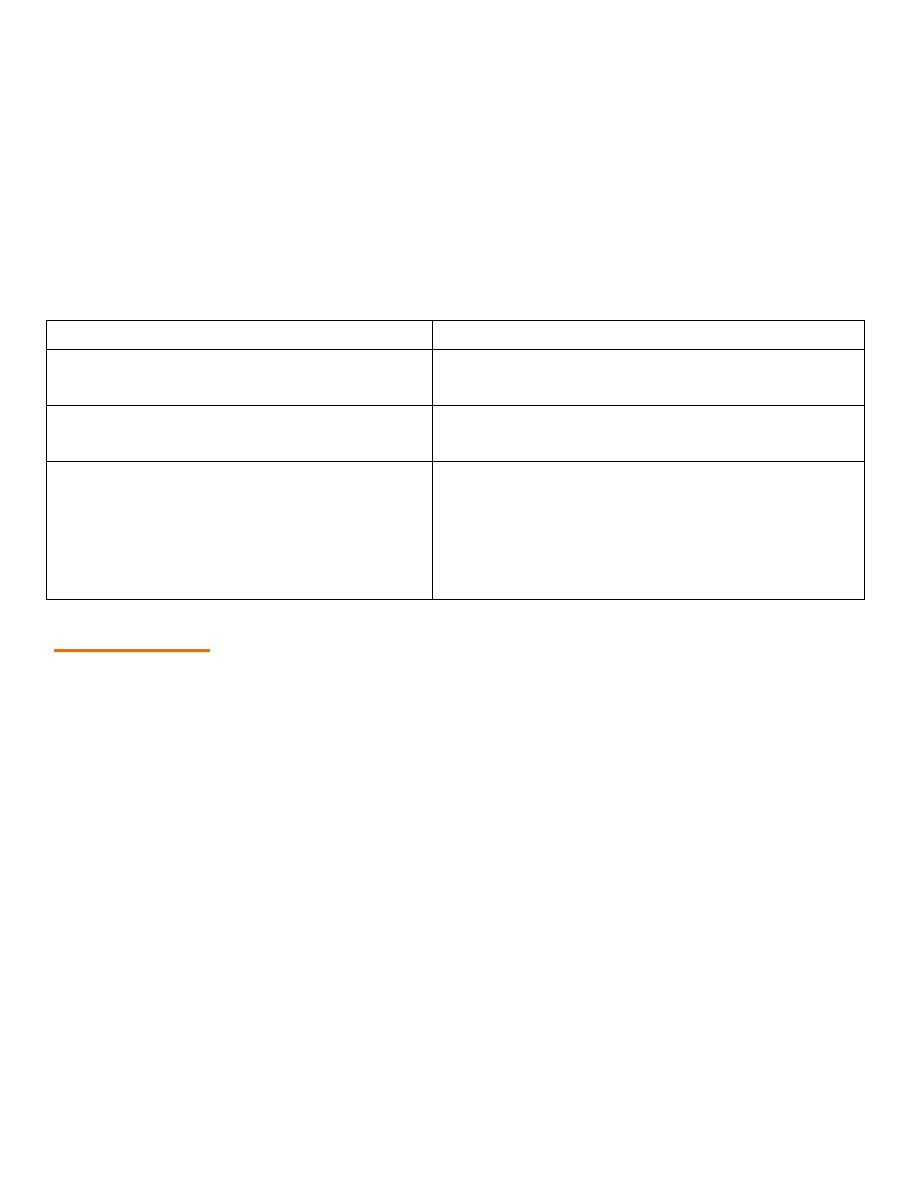

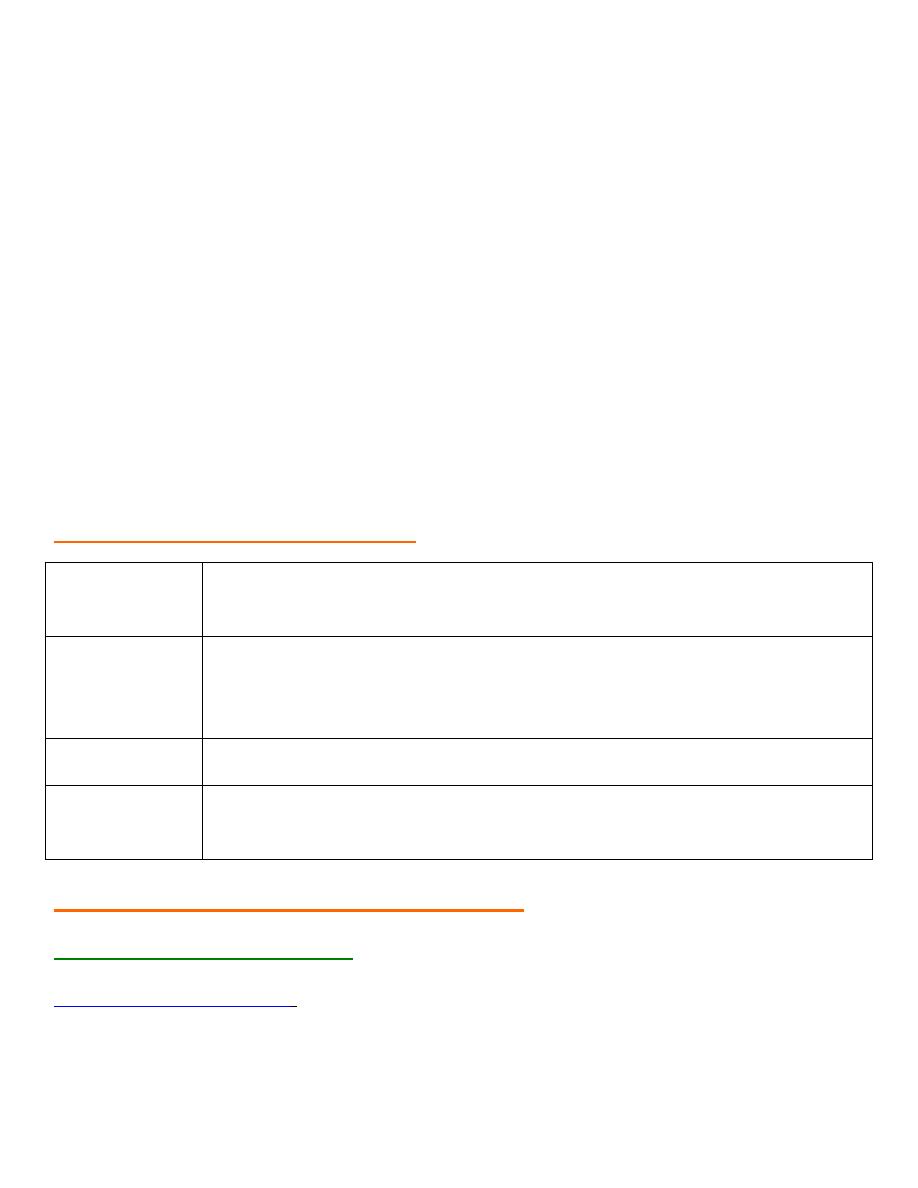

Ordinary Oedema

Lymphoedema

Pitting.

Nonpitting(due to excessive collagen

deposition).

Involves epifascial, subfascial and

muscle compartments.

Is confined to the epifascial space only.

capillary filtration rate is

pathologically high and overwhelms a

normal lymphatic system, resulting in

the accumulation of low-protein

oedema fluid.

capillary filtration is normal but there is an

abnormal lymphatic drainage system and

the oedema fluid is relatively high in

protein.

In general, primary lymphoedema progresses more slowly than secondary

lymphoedema. Two main types of lymphoedema are recognised:

Classification

1- Primary lymphoedema

, in which the cause is unknown (or at least uncertain

and unproved), but often presumed to be due to (congenital lymphatic dysplasia),

Primary lymphoederna is usually further subdivided on the basis the presence of

family, age of onset and lymphangiographic findings:

a - Congenital

(onset < 2 years old).

· Sporadic.

· Familial (Milroy’s disease).

b - Praecox

(onset 2 - 35 years old).

· Sporadic.

· Familial (Meige’s disease).

c - Tarda

(onset after 35 years old).

2- Secondary lymphoedema

, in which there is a clear underlying cause, such as

inflammation, malignancy or surgery.

1- Infection

.

a - Parasitic infection (filariasis).

b - Fungal infection (tinea pedis).

2- Exposure to foreign body material

(silica particles).

3- Malignancy

.

a- Primary lymphatic malignancy.

b- Metastatic spread to lymph nodes.

4- Surgery

. Excision of LNs.

5- Radiotherapy

. to groups of lymph nodes.

6- Trauma

. (particularly degloving injuries).

7- Venous complications

.

a- Superficial thrombophlebitis.

b- Deep venous thrombosis.

Grade

(

Brunner

)

Clinical classification of lymphoedema

Clinical features

Subclinical

(latent)

I

Oedema pits on pressure and the swelling largely, or completely

disappears on elevation and bed rest.

II

Oedema does not pit and does not significantly reduce upon elevation.

Ill

Oedema is associated with irreversible skin changes, i.e. fibrosis,

papillae.

Differential diagnosis of the swollen limb

(1) Non-vascular or lymphatic

1- Cardiac failure from any cause.

1) General disease states

.

2- Liver failure.

3- Hypoproteinaemia due to nephrotic syndrome, malabsorption, protein- losing

enteropathy.

4- Hypothyroidism (myxoedema).

5-Allergic disorders, including angioedema and idiopathic cyclic oedema.

6-Prolonged immobility and lower limb dependency.

2) Local disease processes

. (Ruptured Baker’s cyst, Myositis ossificans, Bony or

soft-tissue tumours, Arthritis, Haemarthrosis, Calf muscle haematoma, Achilles

tendon rupture).

3) Retroperitoneal fibrosis

.May lead to arterial,venous and lymphatic abnormalities.

4) Gigantism

. (Rare, all tissues are uniformly enlarged).

5) Drugs

. Corticosteroids (oestrogens, progestagens), Monoamine oxidase

inhibitors (phenylbutazone, methyldopa, hydralazine, nifedipine).

6) Trauma

. Painful swelling due to reflex sympathetic dystrophy

7) Obesity

. (Lipodystrophy, Lipoidosis).

(2)Venous

:

1) Deep venous thrombosis

.(There may be an obvious predisposing factor, such as

recent surgery,The classical signs of pain and redness may be absent).

2) Post-thrombotic syndrome

. (Swelling, usually of the whole leg, due to

iliofemoral venous obstruction,Venous skin changes, secondary varicose veins on

the leg and collateral veins on the lower abdominal wall,Venous claudication may

be present).

3) Varicose veins

. Simple primary varicose veins are rarely the cause of significant

leg swelling.

4) Klippel—Trenaunay syndrome and other malformations

. (Rare) Present at birth

or develops in early childhood, Comprises an abnormal lateral venous complex,

capillary naevus, bony abnormalities, hypo(a)plasia of deep veins and limb

lengthening, Lymphatic abnormalities often coexist.

5) External venous compression

. Pelvic or abdominal tumour including the gravid

uterus, Retroperitoneal fibrosis.

6) lschaemia—Reperfusion

.

Following lower limb revascularisation for chronic

ischaemia.

(3) Arterial

1) Arteriovenous malformation

. May be associated with local or generalised

swelling

2) Aneurysm

. (Popliteal, Femoral, False aneurysm following (iatrogenic) trauma).

1- Lyrnphangiosarcoma (Stewart—Treve’s syndrome).

2- Kaposi’s sarcoma (human immunodeficiency virus, HIV).

3- Squamous cell carcinoma.

4- Liposarcoma.

5- Malignant melanoma .

6- Malignant fibrous hisfiocytoma.

7- Basal cell carcinoma.

8- Lymphoma.

Malignancies associated with lymphoedema

INVESTIGATION OF LYMPHOEDEMA

(1) Routine tests

:

1-Full blood count, 2-Urea and electrolytes, creatinine. 3- Liver function tests. 4-

Chest radiography. 5-Blood smear for microfilariae.

(2) Lymphangiography

:

1- Direct lymphangiography

involves the injection of contrast medium into a

peripheral lymphatic vessel and subsequent radiographic visualisation of the vessels

and nodes. It remains the ‘gold standard’ for showing structural abnormalities of

larger lymphatics and nodes. However, it can be technically difficult, it is

unpleasant for the patient, it may cause further lymphatic injury and, largely, it has

become obsolete as a routine method of investigation. Few centres now perform this

technique and those that do generally reserve it for preoperative evaluation of the

rare patient with megalymphatics who is being considered for bypass or fistula

ligation.

2-Indirect lymphangiography

involves the intradermal injection of water- soluble,

non-ionic contrast into a web space, from where it is taken up by lymphatics and

then followed radiographically, It will show distal lymphatic but not normally

proximal lymphatics and nodes.

(

3) Isotope Lymphoscintigrcaphy

:

This has largely replaced lymphangiography as the primary diagnostic technique in

cases of clinical uncertainty. Radioactive technetium-labelled protein or colloid

particles are injected into an interdigital web space and specifically taken up by

lymphatics, and serial radiographs are taken with a gamma camera. The technique

provides a qualitative measure of lymphatic function rather than quantitative

function or anatomical detail.

(4) Computerised Tomography

A single, axial computerised tomography (CT) slice through the midcalf has been

proposed as a useful diagnostic test for lymphoedema (coarse, non-enhancing,

reticular ‘honeycomb’ pattern in an enlarged subcutaneous compartment), venous

oedema (increase volume of the muscular compartment), and lipoedema (increased

subcutaneous fat). CT can also be used to exclude pelvic or abdominal mass lesions.

(

5) Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide clear images of lymphatic channels

and lymph nodes, and can be useful in the assessment of patients with lymphatic

hyperplasia. MRI can also distinguish venous and lymphatic causes of a swollen

limb.

(6) Ultrasound

Ultrasound can provide useful information about venous function.

MANAGEMENT OF LYMPHOEDEMA

(1) Relief of pain

On initial presentation, 50% of patients with lymphoedema complain of significant

pain. The pain is usually multifactorial and its severity and underlying cause(s) will

vary depending on the aetiology of the lymphoedema. For example, following

treatment for breast cancer, pain may arise from the swelling itself, (radiation and

surgery induced) nerve (brachial plexus and intercostobrachial nerve), bone

(secondary depositis, radiation necrosis) and joint disease (arthritis, bursitis,

capsulitis), and recurrent disease

.

Use of

(1)non-opioid(

NSAIDs

) and (2)

opioid analgesics

, (3)

corticosteroids

,

(4)

tricyclic antidepressants

, (5)

muscle relaxants

, (6)

anti-epileptics

, (7)

nerve blocks

,

(8)

physiotherapy

, (9)

adjuvant anti-cancer therapies

(chemo-, radio- and hormonal

therapy).

(2) Control of swelling

Physical therapy for lymphoedema comprising

1-bed rest

,

2-elevation

,

3-bandaging

,

4-compression garments, 5-massage and 6-exercises. The current preferred term is

decongestive lymphoedema therapy (DLT)

and comprises two phases. The first is a

short

intensive period

of therapist-led care and the second is a

maintenance phase

in

which the patient uses a self-care regimen with occasional professional intervention.

The intensive phase comprises skin care, manual lymphatic drainage (MLD) and

multi-layer lymphoedema bandaging (MLLB), and exercises.

(3) Skin care

1- Protect hands when washing up or gardening; wear a thimble when sewing.

2- Never walk barefoot and wear protective footwear outside.

3- Use an electric razor to depilate.

4- Never let the skin become macerated.

5- Treat cuts and grazes promptly (wash, dry, application of antiseptic and a

plaster).

6- Use insect repellent sprays and treat bites promptly with antiseptics and

antihistamines.

7- Seek medical attention as soon as limb becomes hot, painful or more swollen.

8- Do not allow blood to be taken from, or injections to be given into the affected

arm (and avoid blood pressure measurement).

9- Protect the affected skin from sun (shade, high factor sun block).

10- Consider taking antibiotics if going on holiday.

(

3) Manual lymphatic drainage

Aim to evacuate fluid and protein from the 1SF space, and stimulate lymphangion

contraction. The therapist should perform MLD daily; they should also train the

patient (and/or carer) to perform a simpler, modified form of massage, termed

simple lymphatic drainage (SLD). In the intensive phase, SLD supplements MLD

and, once the maintenance phase is entered, SLD will carry on as daily massage.

(4) Multilayer lymphoedema bandaging and compression garments

Elastic bandages

provide compression, produce a sustained high resting pressure

and ‘follow in’ as limb swelling reduces. However, the sub-bandage pressure does

not alter greatly in response to changes in limb circumference consequent upon

muscular activity and posture. By contrast, short-stretch bandages exert support

through the production of a semi-rigid casing where the resting pressure is low but

changes quite markedly in response to movement and posture. It is generally

believed that non-elastic multilayer lymphoedema bandaging (MLLB) is preferable

(and arguably safer) in patients with severe swelling during the intensive phase of

DLT, whereas compression (hosiery, sleeves) is preferable in milder cases and

during the maintenance phase. Whether the aim is to provide support or

compression, the pressure exerted must be graduated (100% ankle/foot, 70% knee,

50% midthigh, 40% groin) and, of course, the adequacy of the arterial circulation

must be assessed.

Compression garments

form the mainstay of management in most clinics. The

control of lymphoedema requires higher pressures (30—40 mmHg arm, 40—60

mmHg leg) than are typically used to treat CVI. The patient should put the stocking

on first thing in the morning before rising. Donning and doffing lymphoedema

grade stockings is difficult and many patients find them intolerably uncomfortable,

especially in warm climates.

Pneumatic compression devices

, Unless the device being used allows the sequential

inflation of multiple chambers up to > 50 mmHg, it will probably be ineffective for

lymphoedema.

(5) Exercise.

Lymph formation is directly proportional to arterial inflow and 40% of lymph is

formed within skeletal muscle. Vigorous exercise, especially if it is anaerobic and

isometric, will tend to exacerbate lymphoedema and patients should be advised to

avoid prolonged static activities, for example carrying heavy shopping bags or

prolonged standing. In contrast, slow, rhythmic, isotonic movements (e.g.

swimming) and massage will increase venous and lymphatic return through the

production of movement between skin and underlying tissues (essential to the

filling of initial lymphatics) and augmentation of the muscle pumps. Exercise also

helps to maintain joint mobility. Patients who are unable to move their limbs benefit

from passive exercises.

(6) Limb Elevation

.

When at rest, the lymphoedematous limb should be positioned with the foot/hand

above the level of the heart. A pillow under the mattress or blocks under the bottom

of the bed will encourage the swelling to go down overnight.

(7) Drugs

.

The

benzpyrones

are a group of several thousand naturally occurring substances, (

flavonoids) they reduce capillary permeability, improve microcirculatory perfusion,

stimulate interstitial macrophage proteolysis, reduce erythrocyte and platelet

aggregation, scavenge free radicals and exert an anti-inflammatory effect

.

Oxerutins

(paroven)

.

Diuretics

are of no value in pure lymphoedema. Their chronic use is associated

with side-effects, including electrolyte disturbance, and should be avoided.

(8) Surgery

Only a small minority of patients with lymphoedema benefit from surgery.

1- Bypass procedures

The rare patient with proximal ilioinguinal lymphatic obstruction and normal distal

lymphatic channels might benefit, from lymphatic bypass. Methods:

1-Omental pedicle.

2-Skin bridge (Gillies).

3-Anastomosing lymph nodes to veins (Neibulowitz).

4-Ileal mucosal patch (Kinmonth).

5-Direct lymphovenous anastomosis.

2- Limb reduction procedures

These are indicated when a limb is so swollen that it interferes with mobility and

livelihood. These operations are not ‘cosmetic’ in the sense that they do not create a

normally shaped leg and are usually associated with significant scarring.

1-Sistrunk

. A wedge of skin and subcutaneous tissue is excised and the wound

closed primarily. This is most commonly carried out to reduce the girth of the thigh.

2-Homans

. First skin flaps are elevated, to allow the excision of a wedge of skin

and a larger volume of subcutaneous tissue down to the deep fascia from beneath

the flaps, which are then trimmed to size to accommodate the reduced girth of the

limb and closed primarily. This is the most satisfactory operation for the calf. The

main complication is skin flap necrosis. There must be at least 6 months between

operations on the medial and lateral sides of the limb and the flaps must not pass the

midline to avoid skin flap necrosis. This procedure has also been used on the upper

limb, but is contraindicated in the presence of venous obstruction or active

malignancy.

3-Thompson

One denuded skin flap is sutured to the deep fascia and buried beneath

the second skin flap (the so-called ‘buried dermal flap’). This procedure has become

less popular as pilonidal sinus formation is common. The cosmetic result is no

better than that obtained with the Homans’ procedure and there is no evidence that

the buried flap establishes any new lymphatic connection with the deep tissues.

4-Charles

This operation was initially designed for filariasis and involved

circumferential excision of all the skin and subcutaneous tissues (lymphoedematous

tissue) down to and including the deep fascia, with coverage using split-skin grafts.

This leaves a very unsatisfactory cosmetic result and graft failure is not uncommon.

However, it does enable the surgeon to reduce greatly the girth of a massively

swollen limb(allows the surgeon to remove very large amounts of tissue and is

particularly useful in patients with severe skin changes).