DR. J abar Etaby Lecture 1

Ascaris lumbricoides and Ascaris suum)

(intestinal roundworms of humans and pigs

)

Introduction:

Ascaris lumbricoides is one of the largest and most common

parasites found in humans. The adult females of this speciescan

measure up to 18 inches long (males are generally shorter), and

it is estimated that 25% of the world's population is infected

with this nematode. The adult worms live in the small

Intestine and eggs are passed in the feces.

Habitat:-

The adult worm lives in the small intestine of man

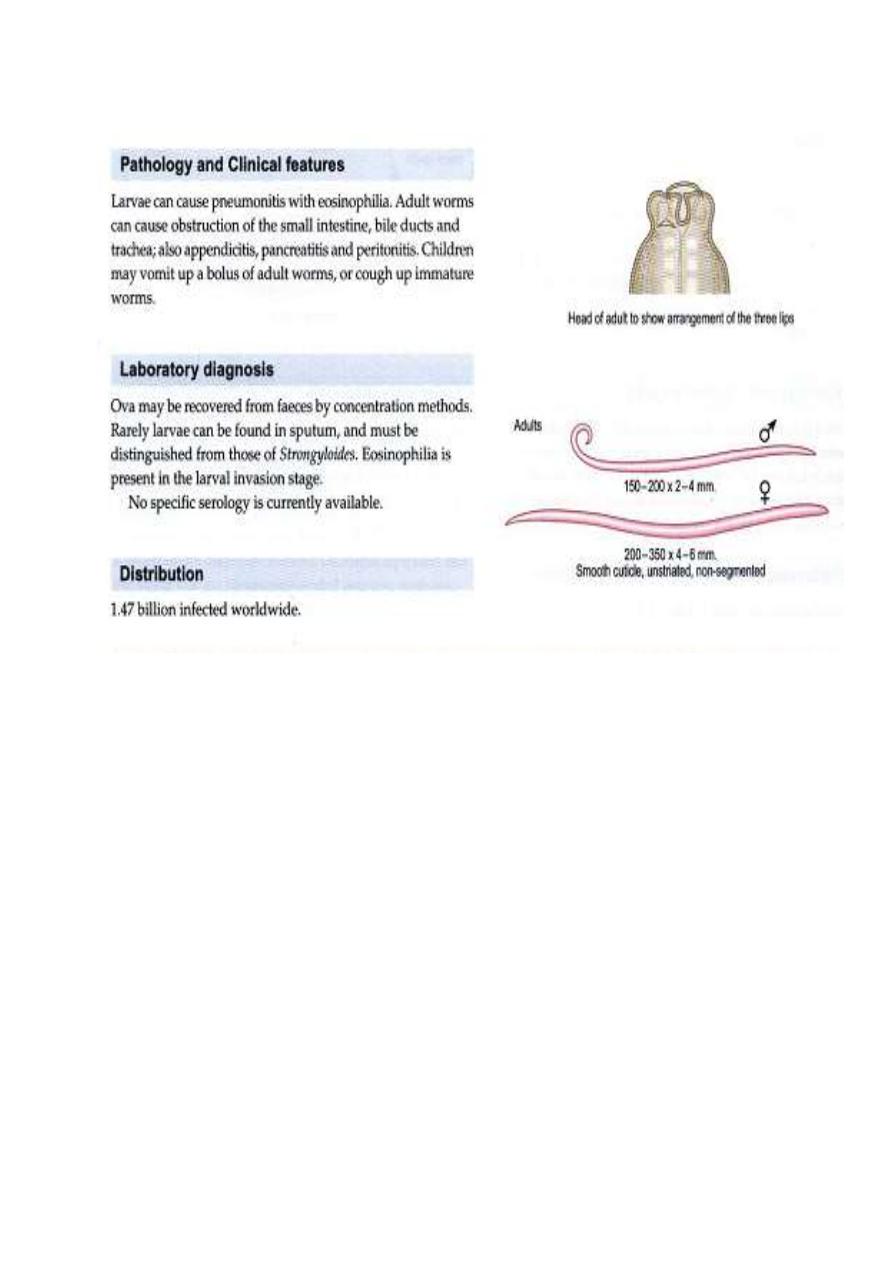

Morphology :-

The adult worm is the largest round worm parasitizing the human

intestinal tract. It is elongated, cylindrical, and tapers both anteriorly

&posteriorly to relatively blunt conical ends. The head is

provided

with three fleshy lips the digestive &reproductive organs float

inside the body cavity which contain an irritating allergic fluid

.The irritant action is due to the presence of atoxin called a

scarone or a scarase which is probably of the nature of primary

albomenoses.

A single female can produce up to 200,000 eggs each day! About two

weeks after passage in the feces the eggs contain an infective larval eggs

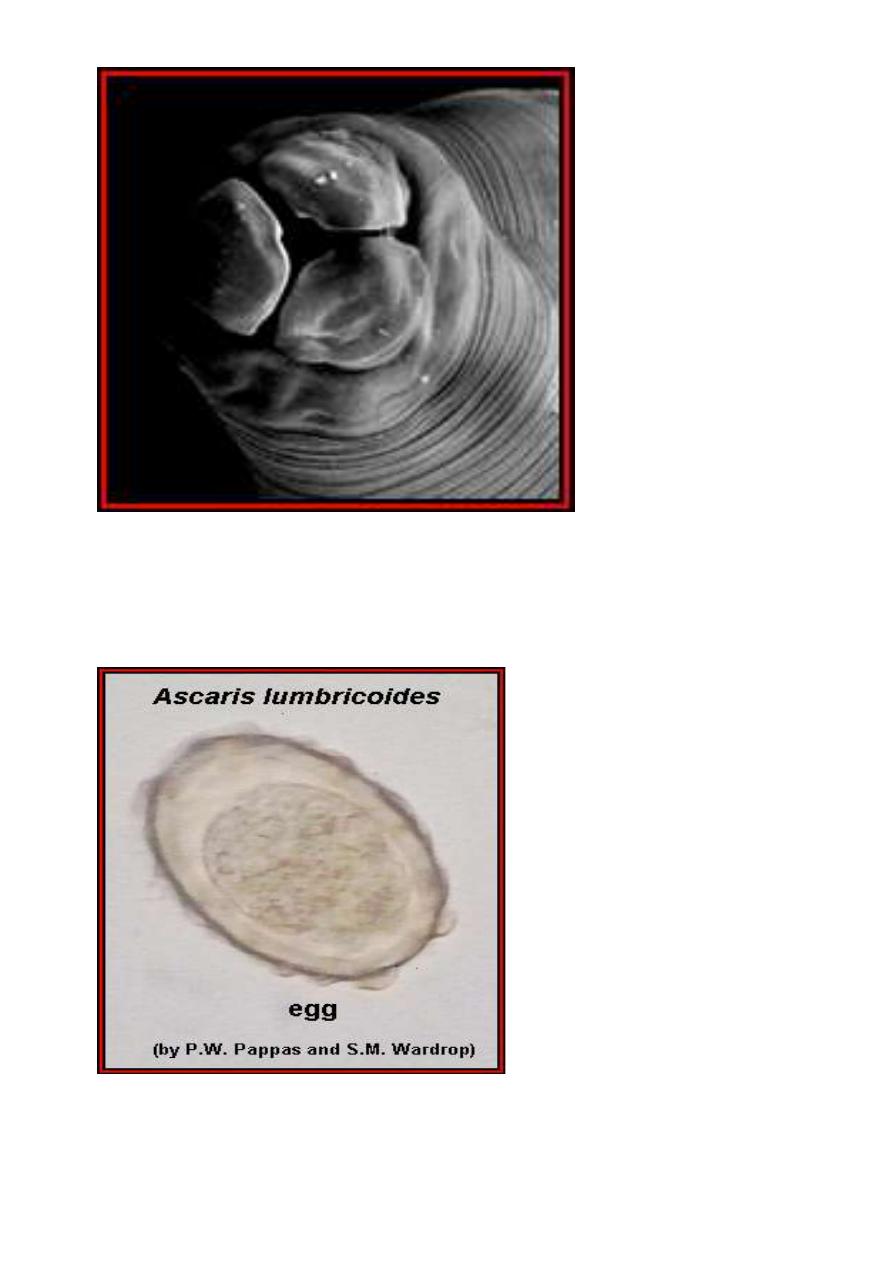

Eggs:

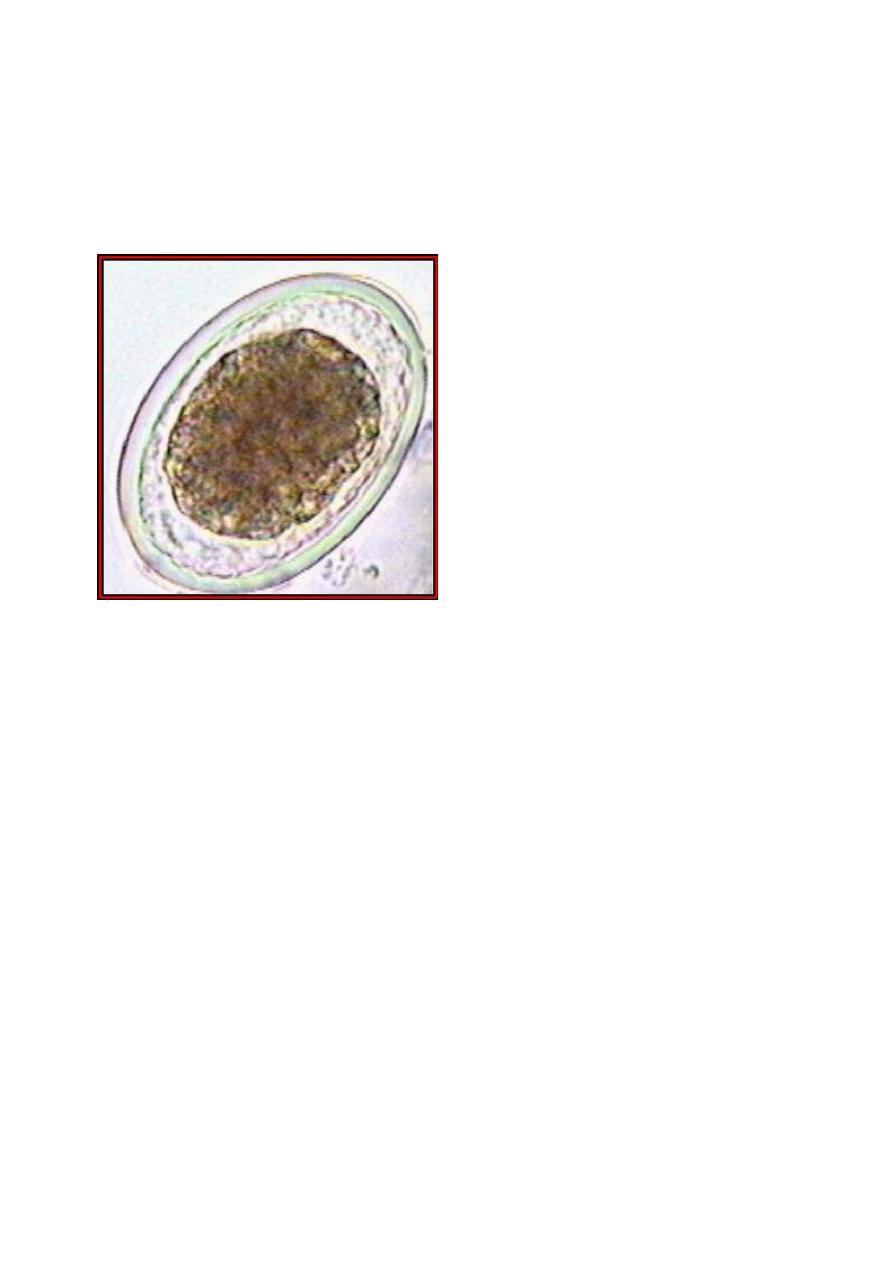

The fertilized egg of Ascaris lumbricoides at the time of oviposition is

spherical or sub-spherical,measures 65-75µmby35-50 µm &consists

of the following observable structures

1-A coarsely granular

,spherical ovum that usually does not completely fill the shell.

2-A thin innermost membrane that is highly impermeable.

3-A relatively thick,colorless middle layer that is smooth on both

inner &outersurfaces .

4-An outermost ,coarsely mammilated

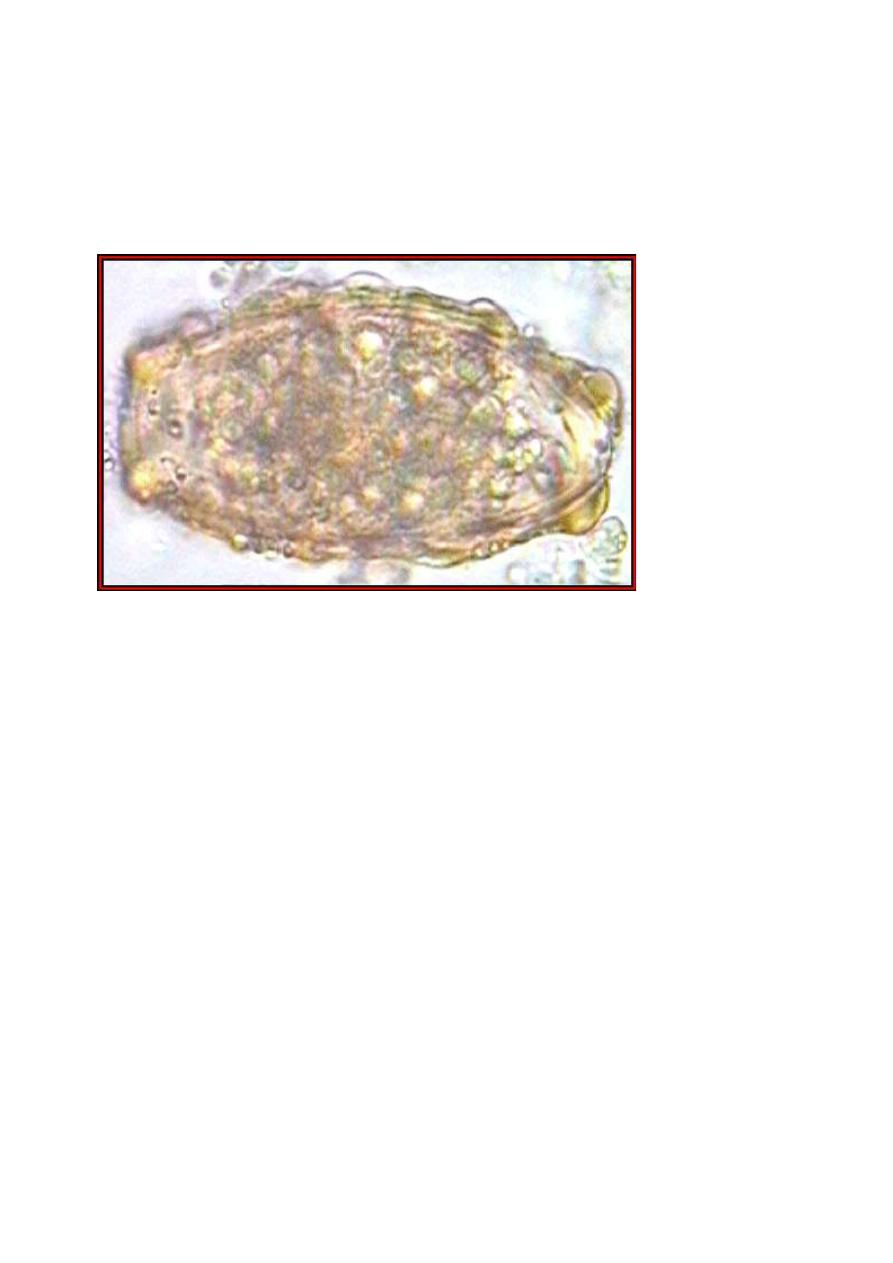

Female worms without males produce infertile eggs that are

markedly subspherical (88 µm by38-44 µm),internally they contain

a mass of disorganized granules that completely fill the shell

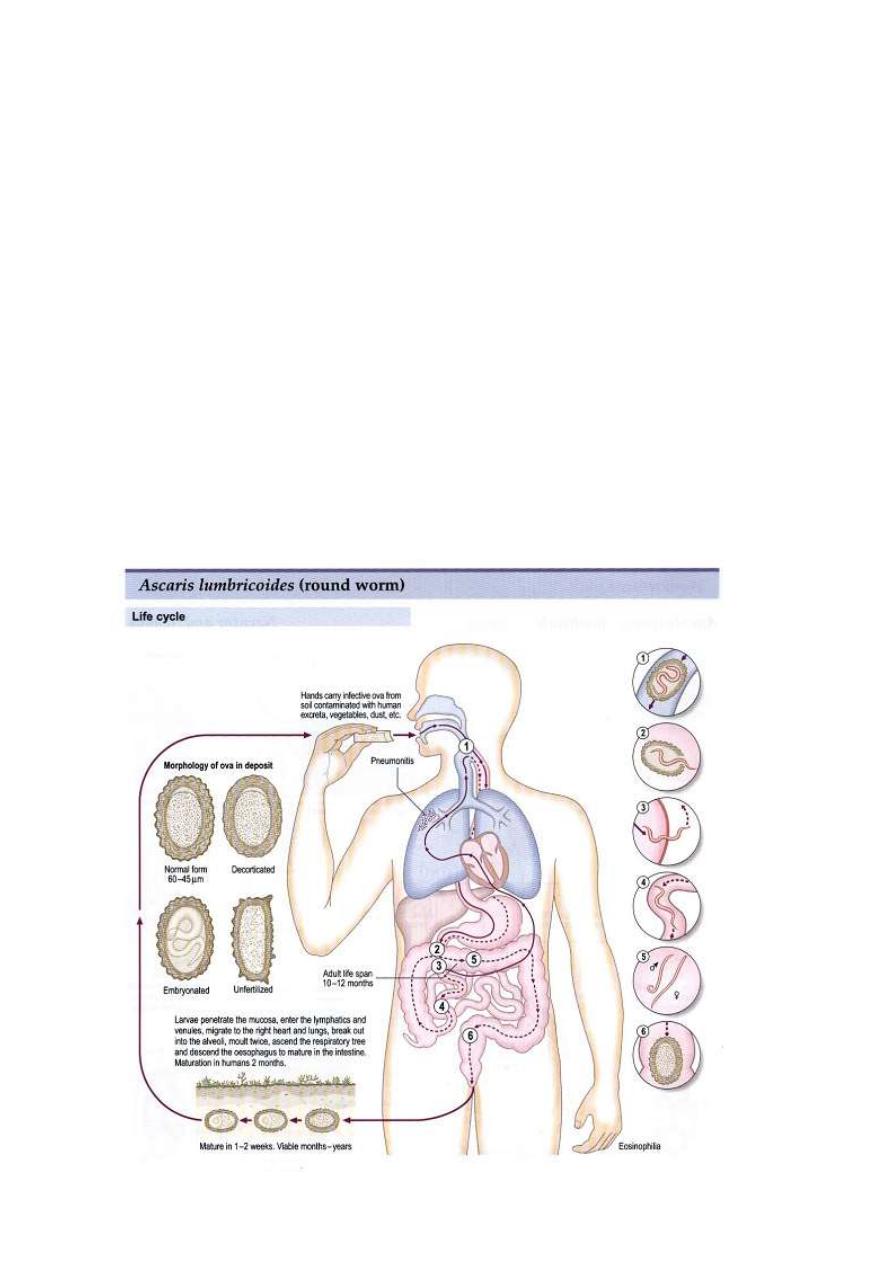

Life cycle, The humans are infected when they ingest such

infective eggs. The eggs hatch in the small intestine, the

juvenile

penetrates the small intestine and enters the circulatory

system, and eventually the juvenile worm enters the lungs.

In the lungs the juvenile worm leaves the circulatory system and

enters the air passages of the lungs. The juvenileworm then

migrates up the air passages into the pharynx where it is

swallowed, and once in the small intestine the juvenilegrows

into an adult worm. Why Ascaris undergoes such a migration

through the body to only end up where it started is unknown.

Such a migration is not unique to Ascaris, as its close relatives

undergo a similar migration in the bodies of

Pathology and symptoms

Ascaris infections in humans can cause significant pathology.

The migration of the larvae through the lungs causes the blood

vessels of the lungs to hemorrhage, and there is an inflammatory

response accompanied by edema. The resulting accumulation of

fluids in the lungs results in "ascaris pneumonia," and this can

be fatal. The large size of the adult worms also presents

problems, especially if the worms physically block the

gastrointestinal tract. Ascaris is not orious for it reputation to

migrate within the small intestine, and when large worm begins

to migrate there is not much that can stop it.

Instances have been reported in which Ascaris havemigratedinto

and blocked the bile or pancreatic duct or in which the worms

have penetrated the small intestine resulting in acute (and fatal)

peritonitis. Ascaris seems to be especiallysensitive to

anesthetics, and numerous cases have been documented where

patients in surgical recovery rooms have had worms migrate

from the small intestine, through the stomach, and out the

patient's nose or mouth. Ascaris

suum is found in pigs. Its life

cycle is identical to that of A. lumbricoides. If a human ingests

eggs of A. suum the larvae will migrate to the lungs and die.

This can cause a particularly serious form of "ascaris

pneumonia." Adult worms of this species do not develop in the

human's intestine. (Some parasitologists believe that there is but

one species of Ascaris that infects both pigs and humans, but

any commentary on this issue is beyond the scope of this web

site.)

Diagnosis

Infections of Ascaris are diagnosed by finding characteristic eggs in

the feces of the infected host

.

Note the presence of three large lips, a characteristic of

ascarids.

A scanning electron micrograph of the anterior end of Ascaris

showing the three prominent "lips

Ascaris lumbricoides, fertilized egg. Note that the egg is

covered with a thick shell that appears lumpy (bumpy) or

mammillated; approximate size = 65 μm in length. Another

example

Another example of a fertilized Ascaris lumbricoides egg.

(Original image from:

Atlas of Medical Parasitology

.)

An example of an unfertilized A. lumbricoides egg. (Original

image from:

Atlas of Medical Parasitology

.)

A "decorticated," fertilized, Ascaris lumbricoides. (Original

image from:

Atlas of Medical Parasitology

Eggs of Ascaris suum. A. suum is a common parasite of pigs.

The eggs are virtually indistinguishable from those of A.

lumbricoides. (Original image from

Oklahoma State University,

College of Veterinary Medicine

.)

female Ascaris lumbricoides. Females of this species can

measure over 16 inches long. This specimen was passed by a

young girl in Florida. (Original image from

DPDx

[Identification and Diagnosis of Parasites of Public Health

Concern]

.)

Female

Female and male Ascaris lumbricoides; the female measures

approximately 16 inches (40 cm) in length.

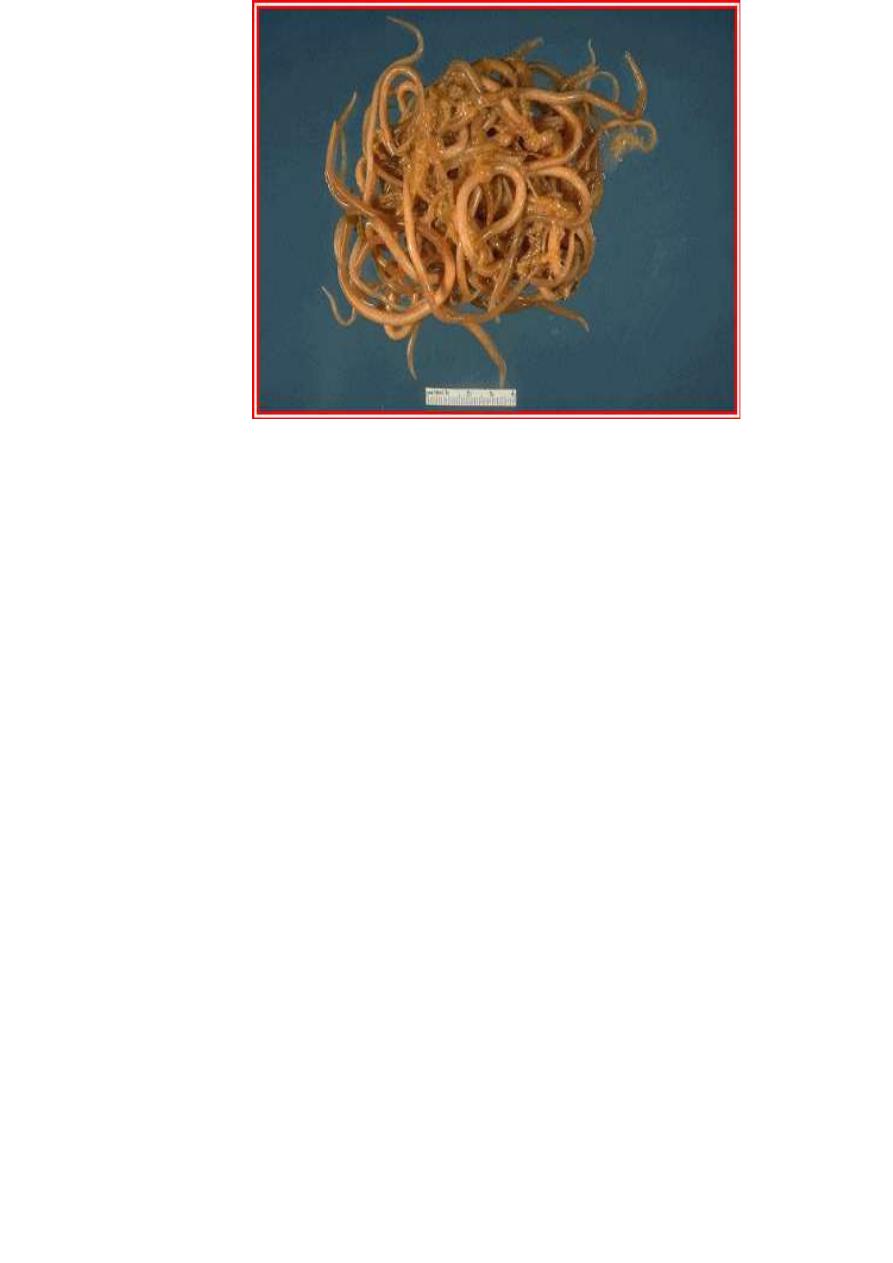

A large mass of Ascaris lumbricoides that was passed from the

intestinal tract. The ruler at the bottom of the image is 4

cm (about 1.5 inches) in length

.

Conclusion

the infective stage is larvated eggs

to cause pneumonia in the lung during circulation& the adult will be bloked

the small intestinal tract

-

up stream movement this movement for A. lumbericoides through mouth

or nose

some times the infected man may die due to this irritation action after

changing to anaphylatic or HSR

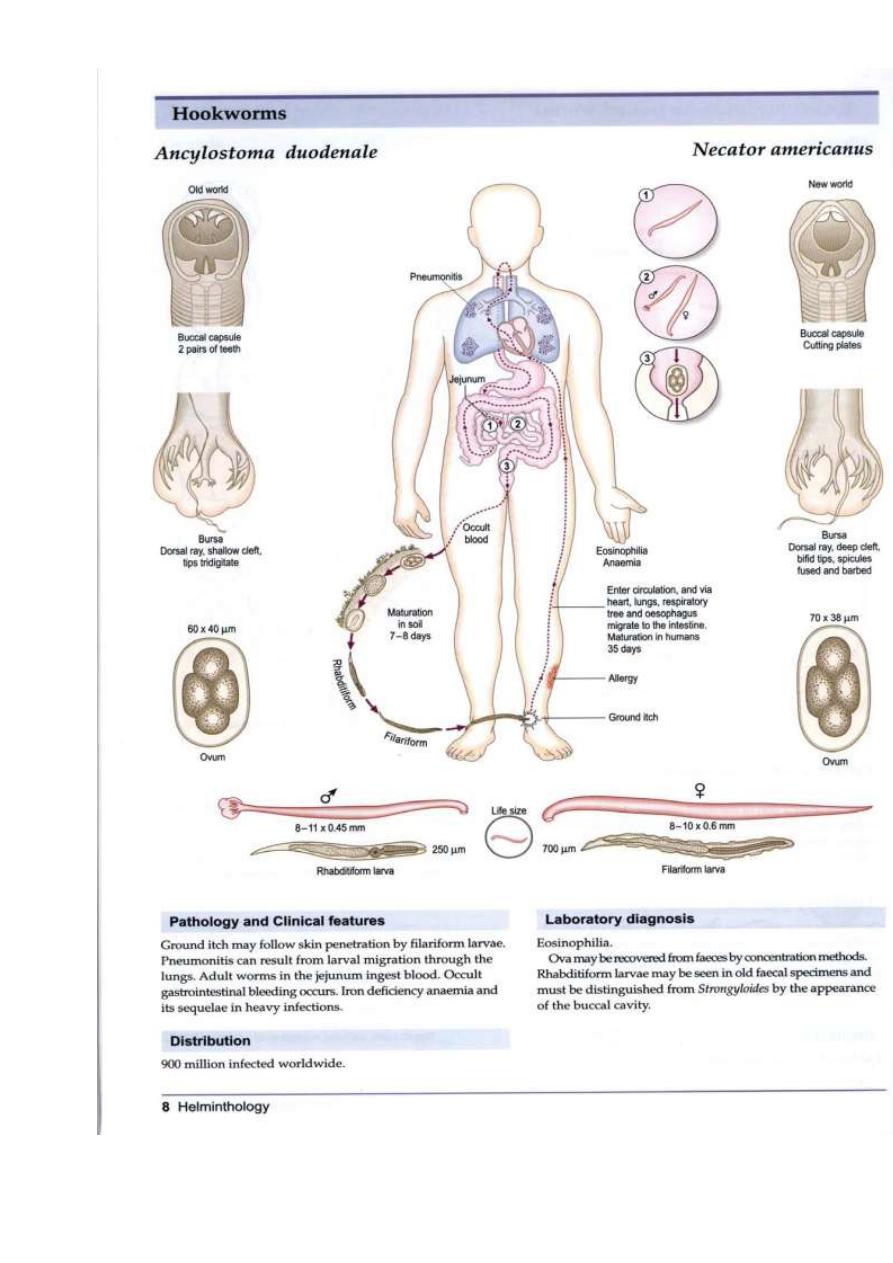

Lecture 2 DR. Jabar Etaby

Introduction

Patients with hookworm infection often are

asymptomatic; however, chronic hookworm infection is

a common cause of moderate and severe hypochromic,

microcytic anemia in people living in tropical

developing countries, and heavy infection can cause

hypoproteinemia with edema.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Humans are the only reservoir. Hookworms are

prominent in rural, tropical, and subtropical areas where

soil contamination with human feces is common.

Although the prevalence of both hookworm species is

equal in many areas, A duodenale is the predominant

species in the Mediterranean region, northern Asia, and

selected foci of South America. N americanus is

predominant in the Western hemisphere, sub-Saharan

Africa, Southeast Asia, and a number of Pacific islands.

LIFE CYCLE

Larvae and eggs survive in loose, sandy, moist, shady,

well-aerated, warm soil (optimal temperature 23°C–

33°C [73°F–91°F]). Hookworm eggs from stool hatch in

soil in 1 to 2 days as rhabditiform larvae. These larvae

develop into infective filariform larvae in soil within 5 to

7 days and can persist for weeks to months.

Percutaneous infection occurs after exposure to

infectious larvae. A duodenale transmission can occur by

oral ingestion and possibly through human milk.

Untreated infected patients can harbor worms for 5

years or longer. The time from exposure to development

of noncutaneous symptoms is 4 to 12 weeks.

Clinical signs

Patients with hookworm infection often are

asymptomatic; however, chronic hookworm infection is a

common cause of moderate and severe hypochromic,

microcytic anemia in people living in tropical developing

countries, and heavy infection can cause

hypoproteinemia with edema. Chronic hookworm

infection in children may lead to physical growth delay,

deficits in cognition, and developmental delay. After

contact with contaminated soil, initial skin penetration of

larvae, often involving the feet, can cause a stinging or

burning sensation followed by pruritus and a

papulovesicular rash that may persist for 1 to 2 weeks.

Pneumonitis associated with migrating larvae is

uncommon and usually mild, except in heavy infections.

Colicky abdominal pain, nausea, and/or diarrhea and

marked eosinophilia can develop 4 to 6 weeks after

exposure. Blood loss secondary to hookworm infection

develops 10 to 12 weeks after initial infection and

symptoms related to serious iron-deficiency anemia can

develop in long-standing moderate or heavy hookworm

infections. After oral ingestion of infectious Ancylostoma

duodenale larvae, disease can manifest with pharyngeal

itching, hoarseness, nausea, and vomiting shortly after

ingestion.

ETIOLOGY

Necator americanus is the major cause of hookworm

infection worldwide, although A duodenale also is an

important hookworm in some regions. Mixed infections

are common. Both are roundworms (nematodes) with

similar life cycles

.

Ancylostoma spp. and Necator spp. (hookworms)

There are many species of hookworms that infect mammals.

The most important, at least from the human standpoint, are

the human hookworms, Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator

americanus, which infect an estimated 800,000,000 persons,

and the dog and cat hookworms, A. caninum and A. braziliense,

respectively. Hookworms average about 10 mm in length

and live in the small intestine of the host. The males and

females mate, and the female produces eggs that are passed in

the feces. Depending on the species, female hookworms can

produce 10,000-25,000 eggs per day. About two days after

passage the hookworm egg hatches, and the juvenile worm (or

larva) develops into an infective stage in about five days.

The next host is infected when an infective larva penetrates the

host's skin. The juvenile worm migrates through the host's

body and finally ends up in the host's small intestine where it

grows to sexual maturity. The presence of hookworms can be

demonstrated by finding the characteristic eggs in the feces; the

eggs can not, however, be differentiated to species

Juveniles (larvae) of the dog and cat hookworms can infect

humans, but the juvenile worms will not mature into adult

worms. Rather, the juveniles remain in the skin where they

continue to migrate for weeks (or even months in some

instances).

This results in a condition known as

"cutaneous" or

"dermal larval migrans"

or "creeping eruption." Hence the

importance of not allowing dogs and cats to defecate

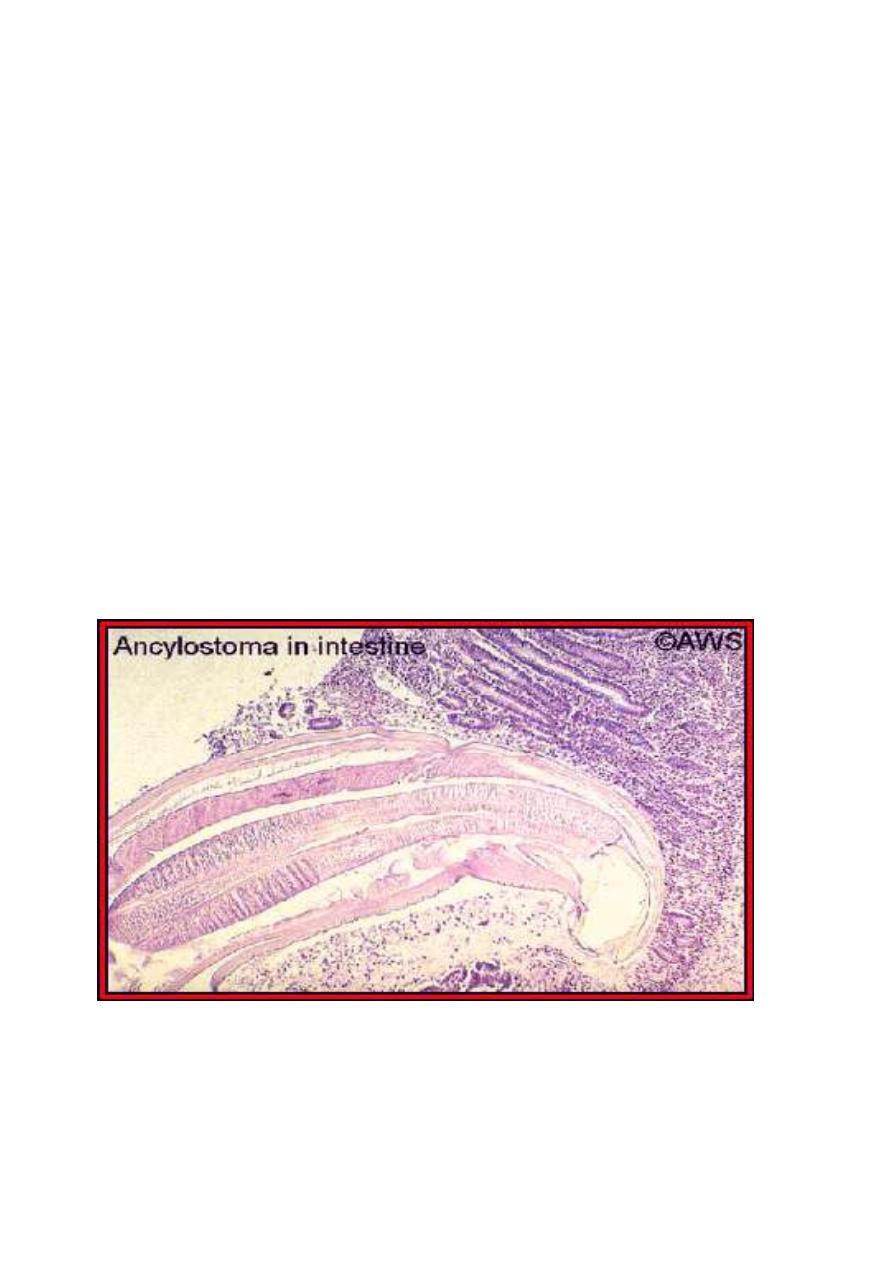

indiscriminately. The following image provides an excellent

example of how hookworms are attached to and embedded in

the epithelium of the host's gastrointestinal tract.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Microscopic demonstration of hookworm eggs in feces is

diagnostic. Adult worms or larvae rarely are seen.

Approximately 5 to 8 weeks are required after infection

for eggs to appear in feces. Adirect stool smear with

saline solution or potassium iodide saturated with iodine

is adequate for diagnosis of heavy hookworm infection;

light infections require concentration techniques.

Quantification techniques (eg, Kato-Katz, Beaver direct

smear, or Stoll egg-counting techniques) to determine

the clinical significance of infection and the response to

treatment may be available from state or reference

laboratories

.

CONTROL MEASURES

Sanitary disposal of feces to prevent contamination of

soil is necessary in areas with endemic infection.

Treatment of all known infected people and screening of

high-risk groups (ie, children and agricultural workers) in

areas with endemic infection can help decrease

environmental contamination. Wearing shoes may not be

fully protective, because cutaneous exposure to

hookworm larvae over the entire body surface of children

could result in infection. Despite relatively rapid

reinfection, periodic deworming treatments targeting

preschool-aged and school-aged children have been

advocated to prevent morbidity associated with heavy

intestinal helminth infections

A histological section of a hookworm in the host's small

intestine. Original image copyrighted and provided by Dr. A.W.

Shostak, and used with permission

Lecture 3 DR. Jabar Etaby

ABSTRACT

Strongyloides stercoralis is an intestinal nematode of humans

that infects tens of millions of people worldwide. S. stercoralis is

unique among intestinal nematodes in its ability to complete its

life cycle within the host through an asexual autoinfective cycle,

allowing the infection to persist in the host indefinitely. Under

some conditions associated with immunocompromise, this

autoinfective cycle can become amplified into a potentially fatal

hyperinfection syndrome, characterized by increased numbers of

infective filariform larvae in stool and sputum and clinical

manifestations of the increased parasite burden and migration,

such as gastrointestinal bleeding and respiratory distress. S.

stercoralis hyperinfection is often accompanied by sepsis or

meningitis with enteric organisms. Glucocorticoid treatment and

human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 infection are the two

conditions most specifically associated with triggering

hyperinfection, but cases have been reported in association with

hematologic malignancy, malnutrition, and AIDS. Anthelmintic

agents such as ivermectin have been used successfully in treating

the hyperinfection syndrome as well as for primary and secondary

prevention of hyperinfection in patients whose exposure history

and underlying condition put them at increased risk.

INTRODUCTION

Strongyloides stercoralis is an intestinal nematode of humans.

It is estimated that tens of millions of persons are infected

worldwide, although no precise estimate is available. Although

most infected individuals are asymptomatic , S. stercoralis is

capable of transforming into a fulminant fatal illness under

certain conditions associated with a compromise of host

immunity. Such conditions have commonly been summarized as

“defects in cell-mediated immunity,” although the specific

circumstances under which S. stercoralis hyperinfection develops

are not always predictable.

Given the increasing numbers of immunocompromised

individuals throughout the world, a closer examination of the

conditions under which S. stercoralis infection becomes

dangerous is warranted. Better approaches to identifying,

screening, and treating those at risk will likely decrease the

morbidity and mortality associated with S. stercoralis infection.

Etiology :

Strongyloides stercoralis

is the Nematodes of small

intestinal tract

Life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis is an unusual "parasite"

in that it has both free-living and parasitic life cycles. In the

parasitic life -cycle, female worms are found in the superficial

tissues of the human small intestine; there are apparently no

parasitic males. The female worms produce larvae

parthenogenically (without fertilization), and the larvae are

passed in the host's feces. The presence of nematode larvae in a

fecal sample is characteristic of strongylodiasis. Once passed in

the feces, some of the larvae develop into "free-living" larvae,

while others develop into "parasitic" larvae. The "free-living"

larvae will complete their development in the soil and mature

into free-living males and females. The free-living males and

females mate, produce more larvae, and (as above) some of

these larvae will develop into "free-living" larvae, while other

will develop into "parasitic larvae." As one might imagine, this

free-living life cycle constitutes an important reservoir for

human infections. The "parasitic" larvae infect the human host

by penetrating the skin (like the

hookworms

). The larvae

migrate to the lungs, via the circulatory system, penetrate the

alveoli into the small bronchioles, and they are "coughed up"

and swallowed. Once they return to the small intestine, the

larvae mature into parasitic females. S. stercoralis also infects

humans via a mechanism called "autoinfection." Under some

circumstances, such as chronic constipation, larvae produced by

the parasitic females will remain in the intestinal tract long

enough to develop into infective stages. Such larvae will

penetrate the tissues of the intestinal tract and develop as if they

had penetrated the skin. Autoinfection can also occur when

larvae remain on and penetrate the perianal skin. Autoinfection

often leads to very high worm burdens in humans (

view

diagram of the life cycle

).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Although S. stercoralis is often considered a disease of tropical

and subtropical areas, endemic foci are also seen in temperate

regions . Low socioeconomic status , alcoholism , white race , and

male gender have been associated with higher prevalences of S.

stercoralis stool positivity. Clusters of cases in institutionalized

individuals with mental retardation others suggest that

nosocomial transmission can occur. Occupations that increase

contact with soil contaminated with human waste, which may

include farming and coal mining depending on local practices,

increase the risk of infection. Swimming in or drinking

contaminated water has not been proven to be a significant

source of transmission, perhaps because larvae do not thrive

when immersed in water . Different prevalences among ethnic

groups may simply reflect behavioral or socioeconomic factors,

but some have suggested that different skin types may be more or

less resistant to larval penetration .

CLINICAL SYNDROMES

As the clinical syndromes of S. stercoralis encompass a spectrum

and terms are used variably, it is necessary to set forth some

definitions before proceeding further.

Acute Strongyloidiasis

From experimental human infections, it is known that a local

reaction at the site of larval entry can occur almost immediately

and may last up to several weeks

.

Pulmonary symptoms such as a

cough and tracheal irritation, mimicking bronchitis, occur as

larvae migrate through the lungs several days later.

Gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, constipation, anorexia,

abdominal pain) begin about 2 weeks after infection, with larvae

detectable in the stool after 3 to 4 weeks. Experimental human

infections on which this description is based were initiated with

many hundreds of larvae and most likely overestimate the

severity and perhaps the tempo of naturally acquired infections.

Chronic Strongyloidiasis

Chronic infection with S. stercoralis is most often asymptomatic .

There are a number of signs and symptoms attributable to

chronic strongyloidiasis that are unrelated to accelerated

autoinfection. Chronic gastrointestinal manifestations, such as

intermittent vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and borborygmus,

are common complaints. Pruritus ani and dermatologic

manifestations such as urticaria and larva currens rashes are also

common . Recurrent asthma and nephrotic syndrome have also

been associated with chronic strongyloidiasis infection.

Complications such as intestinal obstruction , ileus

hemodynamically significant gastrointestinal bleeding, and acute

worsening of chronic intestinal manifestations have occurred in

the context of an increased larval burden. Even in the absence of

pulmonary symptoms, such presentations could be considered a

manifestation of hyperinfection

Hyperinfection

Hyperinfection describes the syndrome of accelerated

autoinfection, generally — although not always the result of an

alteration in immune status. Parasitologically, the distinction

between autoinfection and hyperinfection is quantitative and not

strictly defined. Therefore, the diagnosis of hyperinfection

syndrome implies the presence of signs and symptoms

attributable to increased larval migration. Development or

exacerbation of gastrointestinal and pulmonary symptoms is

seen, and the detection of increased numbers of larvae in stool

and/or sputum is the hallmark of hyperinfection. Larvae in

nondisseminated hyperinfection are increased in numbers but

confined to the organs normally involved in the pulmonary

autoinfective cycle (i.e., gastrointestinal tract, peritoneum, lungs),

although enteric bacteria, which can be carried by the filariform

larvae or gain systemic access through intestinal ulcers, may

affect any organ system

.

Disseminated Infection

The term disseminated infection is often used to refer to

migration of larvae to organs beyond the range of the pulmonary

autoinfective cycle. This does not necessarily imply a greater

severity of disease. Extrapulmonary migration of larvae has been

shown to occur routinely during the course of experimental

chronic S. stercoralis infections in dogs and has been reported to

cause symptoms in humans without other manifestations of

hyperinfection syndrome Similarly, many cases of hyperinfection

are fatal without larvae being detected outside the pulmonary

autoinfective route.

As documenting disseminated infection may be more a matter of

vigilance than a fundamental difference in disease mechanisms,

the term hyperinfection will be used here to include cases with

evidence of larval migration beyond the pulmonary autoinfective

route.

CONCLUSIONS

Our understanding of S. stercoralis infections in normal and

immunocompromised hosts continues to evolve. Relatively

recently, it was thought that any defect in cellular immunity could

tip the equilibrium of chronic strongyloidiasis toward

hyperinfection. Although various immunocompromising

conditions have been associated with hyperinfection,

Lecture 4 DR. Jabar Eaby

Cutaneous (dermal) larval migrans

There are several examples of parasites that are normally found in pets but can be

transmitted to humans. For example, acommon tapeworm of dogs,

Dipylidium

caninum

, can be transmitted to humans. Immature forms of the common

roundworm of dogs,

Toxocara canis

can also be found in humans, causing a

disease known as

visceral larval migrans

.

Immature forms of both cat and dog hookworms can also infect humans, and this

results in a disease called cutaneous or

dermal larval migrans (CLM or DLM).

The eggs of dog and cat hookworms hatch after being passed in the host's feces,

and the next host is infected when these

larvae penetrate the host's skin. Unfortunately, these larvae can not tell the skin of

one animal from another, so they will

penetrate human skin if they come in contact with it. However, a human is an

unnatural host, so the larvae do not enter the blood stream as they would in a dog

or cat. Rather, they remain in the skin for extended periods of time (weeks or

months in some instances) and finally die. As the larvae migrate through the skin

and finally die, there is an inflammatory response, and the progress of the larvae

through the skin can actually be followed since they leave a tortuous "track" of

inflammed tissue just under the surface of the skin. Treatment of such infections

requires surgical removal of the migrating larvae. Considering the location of

larvae, just under the skin, in light infections this can be done under local

anesthesia and is a relatively simple procedure. Infections involving large numbers

of larvae can be very uncomfortable, and treatment (removal) might require

general anesthesia and supportive treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs.

How do humans come in contact with the larvae of dog and cat hookworms? A

common source of infection in developed countries is probably sandboxes. If you

have a sandbox in your backyard, it is almost certain that cats in the neighborhood

are using it as a large litter box. Moreover, the sand provides a nearly ideal

environment for the hookworm eggs to develop and hatch and for the larvae to

survive. Thus, keeping sandboxes covered to prevent cats from defecating in them

is a worthwhile "ounce of prevention." Other places where cats might defecate are

also possible sources of infection, including flower beds and vegetable gardens.

Dogs are much less fastidious about where they defecate, so it is more difficult to

control dog feces as a possible source of infection. If you own a dog two measures

that you should take are (1) keep you dog free of hookworms and (2) make sure

that you clean up the dog's feces on a regular basis. Also, if you "walk" your dog

in a park or playground, and in particular in my front yard, make sure that you

pick up and dispose of any fecal material the dog might leave behind.

CLM of the foot.

(Original image from:

Companion Animal Surgery

.")

CLM of the foot.

CLM (Original image from and copyrighted by

Dermatology Internet Service,

Department of Dermatology, University of

Erlangen

.)

CLM of the foot.

(Original image from and copyrighted by

Dermatologic Image Database,

Department of Dermatology, University of Iowa

College of Medicine

).

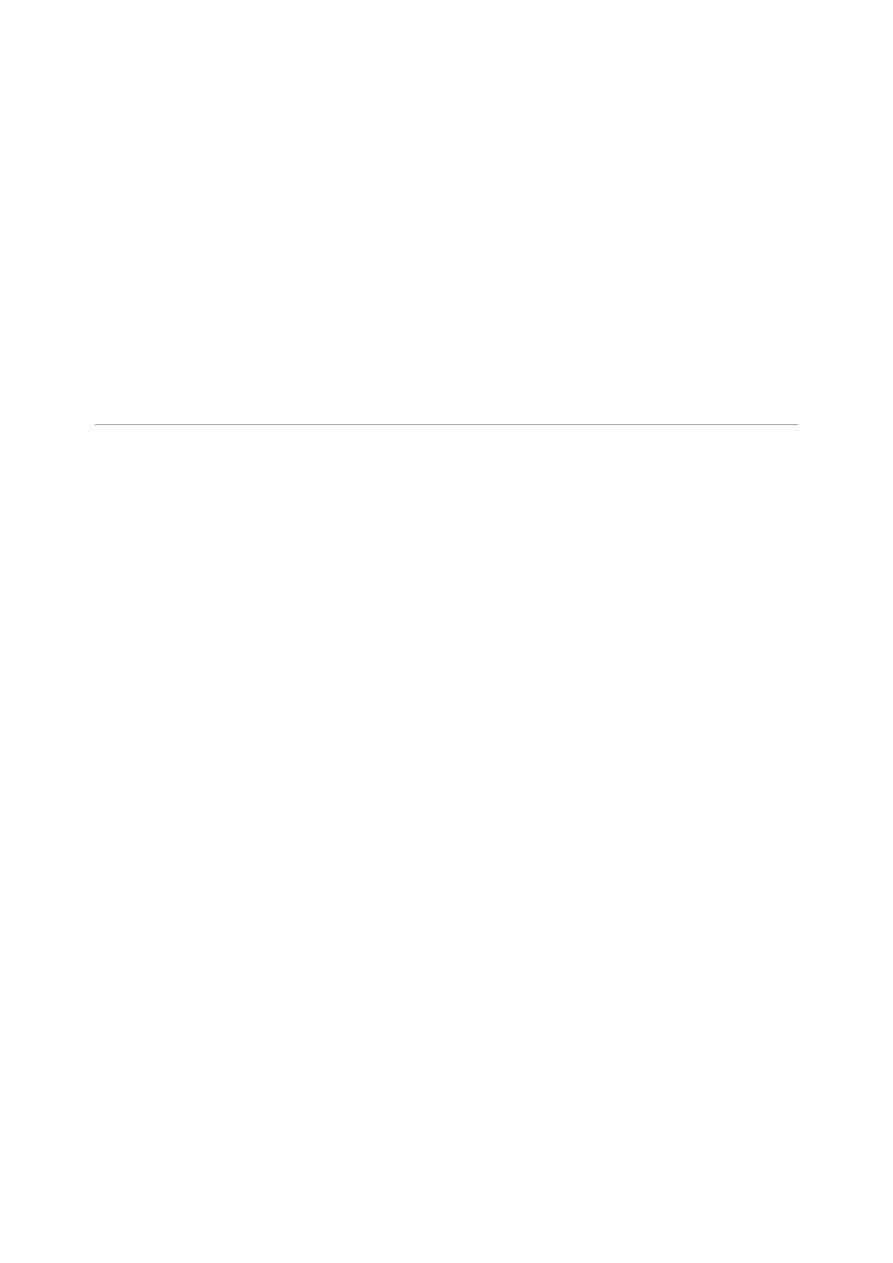

Strongyloides stercoralis in the wall of the small intestine; numerous

adults are visible in this section, as is the abnormal appearance of the

intestinal mucosa.

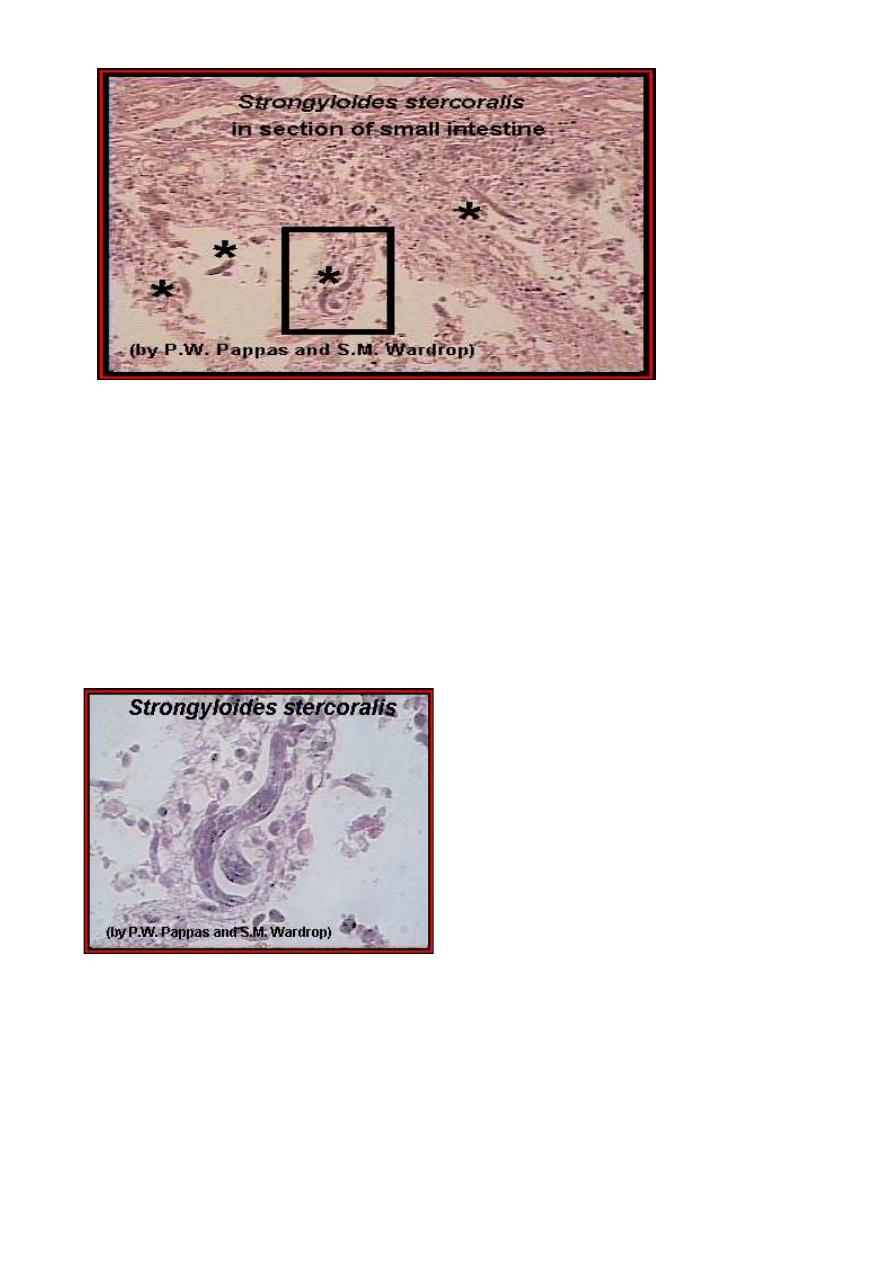

A higher power magnification of the above image; the adult worms are

labeled (*), and a higher power magnification of the enclosed area is

shown in the following image. An enlargement

An enlargement of the enclosed area in the above image

Strongyloides stercoralis adults in the small intestine. (From "Parasite of the

Month.")

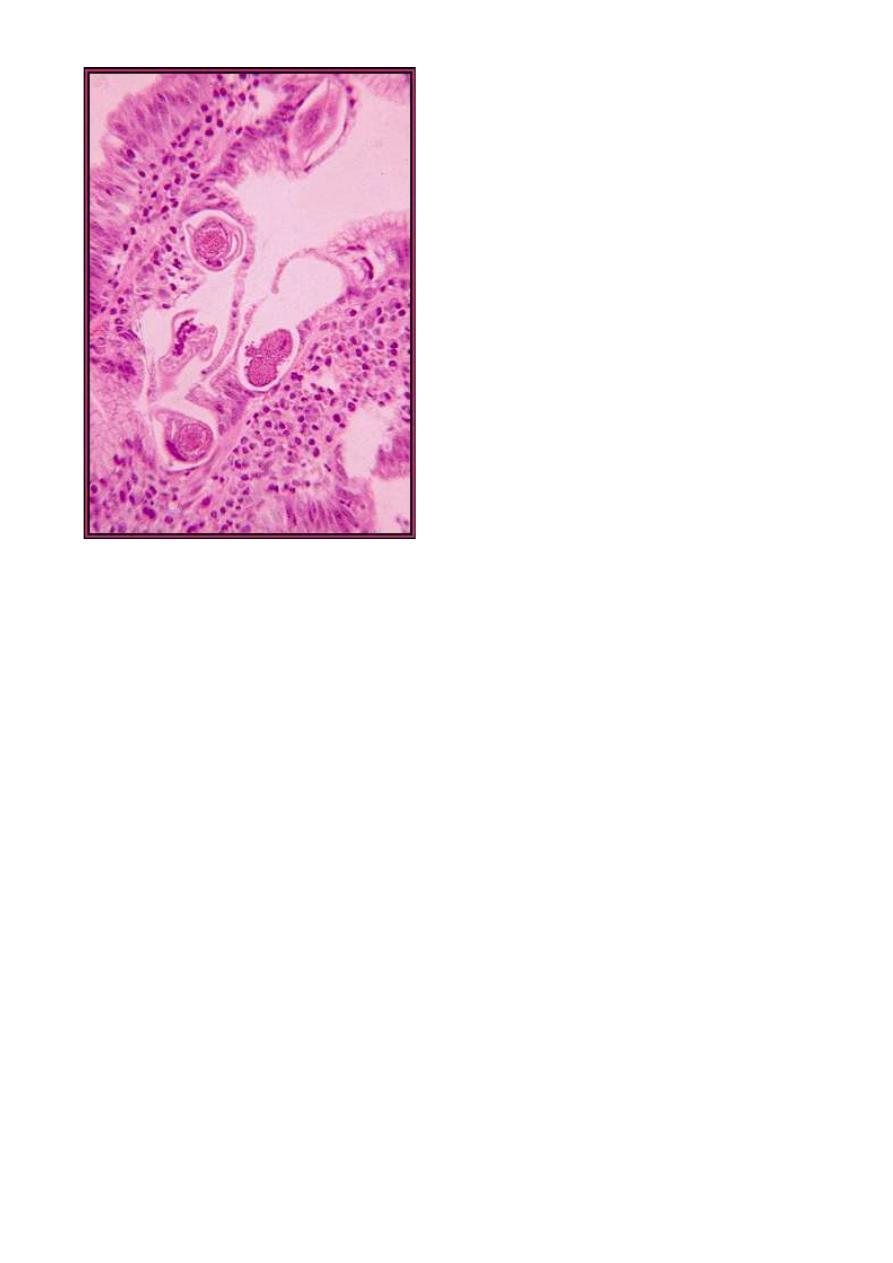

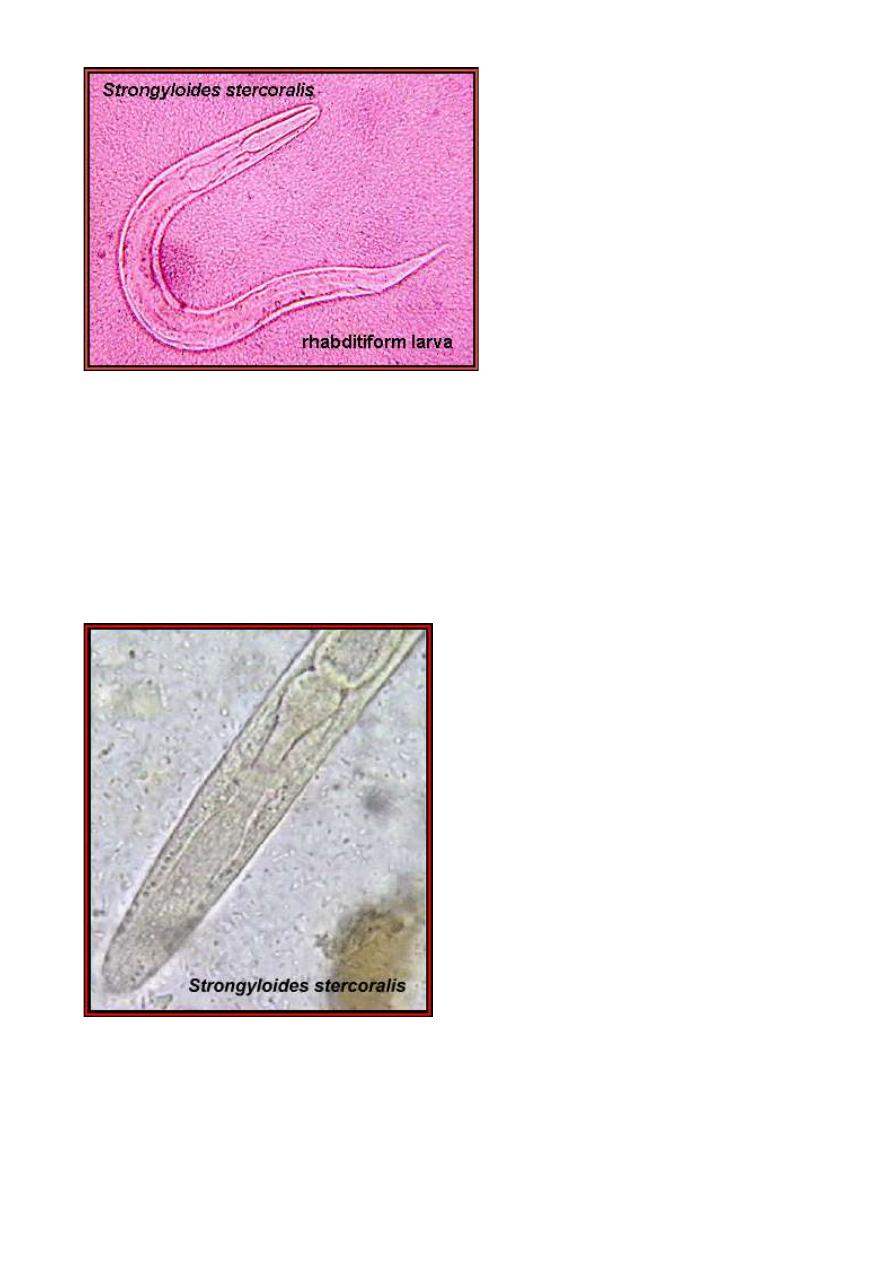

Strongyloides stercoralis larva as it would appear in a fecal sample.

Note the rhabditiform esophagus. (From "Parasite of the Month

Another example of the larva in which the rhabditiform esophagus

shows up clearly. (Original image from "Atlas ofMedical Parasitology

.")

CONCLUSIONS

Our understanding of S. stercoralis infections in normal and

immunocompromised hosts continues to evolve. Relatively recently, it

was thought that any defect in cellular immunity could tip the

equilibrium of chronic strongyloidiasis toward hyperinfection.

Although various immunocompromising conditions have been

associated with hyperinfection, steroids and HTLV-1 infection are the

most consistent